October 25, 2017

F-Bomb: Dispatches From the War on Feminism, by Lauren McKeon

There were women who actively campaigned against universal suffrage. When I learned about this a while ago, the revelation stunned me—but also was something of a comfort. That this kind of lunacy was not without precedent, I mean. That women (and people in general) have always been self-defeating and so obstinate. It’s almost admirable. Almost. But not really, because it’s also dangerous and stupid and it terrifies me. Last fall I spent an inordinate amount of time arguing with strangers on twitter about feminism, in one circumstance about why MPs shouldn’t have to put up with being called “ugly cunt” and threatened with rape or death, for example. Suggesting that this was a gender problem, mostly because this sort of thing didn’t happen to MPs who weren’t women, but plenty of women disagreed with me. Online abuse, they informed me, is simply part of life, and to suggest that women weren’t tough enough to take it, to roll with the punches, was a blatant example of sexism. And it was roundabout this point that my brain twisted into a pretzel shape, and then my head completely exploded.

There were women who actively campaigned against universal suffrage. When I learned about this a while ago, the revelation stunned me—but also was something of a comfort. That this kind of lunacy was not without precedent, I mean. That women (and people in general) have always been self-defeating and so obstinate. It’s almost admirable. Almost. But not really, because it’s also dangerous and stupid and it terrifies me. Last fall I spent an inordinate amount of time arguing with strangers on twitter about feminism, in one circumstance about why MPs shouldn’t have to put up with being called “ugly cunt” and threatened with rape or death, for example. Suggesting that this was a gender problem, mostly because this sort of thing didn’t happen to MPs who weren’t women, but plenty of women disagreed with me. Online abuse, they informed me, is simply part of life, and to suggest that women weren’t tough enough to take it, to roll with the punches, was a blatant example of sexism. And it was roundabout this point that my brain twisted into a pretzel shape, and then my head completely exploded.

And so while the general content of Lauren McKeon’s new book, F-Bomb: Dispatches from the War of Feminism, would not come as news to me, the book itself actually proved to be a comfort. Showing me that I hadn’t gone completely insane, for example, as my conversations on Twitter were really causing me to think I had, and that anti-feminism is indeed an actual phenomenon. Which, when unarticulated, seems encroaching and awful, when suddenly everyone who’s wrong gets to be right (and very loud). But McKeon situates the phenomenon in its own context and the context of our current political nonsensicalness, and her analysis actual made me feel better. As in, here is a thing and it’s insane but it’s also graspable, and the only thing any thinking person can do is try to understand it and to learn.

“[E]early feminists…largely protested abortion, at least in public. Still, as much as we owe a debt to these women, I’m not about to grab a petticoat and try to be them. I might picture myself standing on their shoulders, but its not in a straight and unwavering line. Rather, it’s an inverted pyramid that allows for pluralities and expansion, a rejection of this idea that it’s good to go backward.”

“An inverted pyramid that allows for pluralities and expansion” is a fair articulation of McKeon’s feminism in general, and I love that. I appreciate too the way that she necessarily complicates the idea of first/second/third/fourth wave feminisms too: “As much as older feminists can seem surprised and baffled by younger feminists, the lines aren’t strictly generational; they’re ideological.” Calling upon a discussion of generational divides by Bitch co-founder Lisa Jervis, McKeon writes: “Categorizing feminism into waves flattens the differences in feminist ideologies within the same generation and discounts the similarities between different ones, all in one fell swoop… When we buy into the wave theory, we forget common goals, like the fight for abortion rights, equal pay, and ending violence against women.”

But while McKeon suggests that feminism can indeed thrive on difference, she affirms that we’re nowhere near there yet. White women, she writes, still have ways to go in confronting their privilege, in complicating their own understandings of feminism, and moving over (or even sitting down) to make room for other voices. “If feminism wants to survive and grow, not shrink, it’s vital that it learn how to communicate within itself.”

Because here’s what feminism is up against, as McKeon delineates in the rest of the book: there is the usual chorus of “I’m not a feminist, but…” people, who are only too happy to benefit from the movement, while contributing nothing to it. Men’s rights organizations are on the rise, and women are jumping on board their bandwagon. McKeon delves into the Men’s Rights movements, while never losing her feminist footing (“The men’s rights movement is fond of saying its members don’t hate women. What a load of BS… That’s akin to saying an abusive husband likes his wife. Whatever, buddy; that’s not the point.”) McKeon finds roots of the movement in 19th century magazine editorials, and in the 1989 Montreal Massacre too, whose perpetrator hated feminists. What’s new, however, is the movement’s modern rebranding toward a superficial notion of equality, claiming a universality due to the women who are happy to be its public face.

McKeon speaks to some of these women, who are unabashed in their contradictions (and, usually, in also their ignorance too). A Thunder Bay housewife who writes about how women shouldn’t have the right to vote (who concedes that her brash online persona is mostly bluster and clickbait—and this is a problem, the damage done by so-called provocateurs who are literally profiting on online outrage). A writer of erotica whose website was trolled by anti-feminists…who led her to their website, and won her over, and now pulls in thousands of dollars per speaking engagement. These women’s con-jobs, McKeon writes, are remarkable: “convincing women to shun victimhood without actually doing anything to make us not victims… They’re like the Houdinis of discrimination and hate, conjuring up amazing illusions. Underneath it all, though, the message is essentially: let’s keep things unequal for women, so everybody wins!”

She goes on to critique opt-out culture and the domestication of pre-feminist gender roles, which feeds right into men’s rights rhetoric and fuels the faux-polarization of stay at home moms and working ones, which obscures realities including class. These nostalgics also forget that 1950s housewives were miserable, purged from postwar jobs and stuck in the suburbs on tranquilizers, and blamed for everything that was wrong with their children. It was not a great time, folks. And those who think it was have misunderstood the intentions of second-wave feminists—McKeon points out that Betty Friedan “wanted better treatment for housewives, not to abolish the role.” The myth of “having it all” was invented not by feminists, but by journalists, who’ve been trying to sell magazines (and pitting women against each other) with it for decades.

It is the context of a conscious effort to keep women out of the workforce that McKeon writes about “Gamergate,” the online movement targeted at abusing women who wanted to have a voice in the video game industry—and precedent for the dumpster fire that was the 2016 US Presidential Election. But it also stands for the way that women are driven out of lots of industries, McKeon posits, often for being pregnant, or having sick children to care for. Or simply because they can’t afford the costs of childcare. And anti-feminists dispute all of this, of course. The wage gap is a lie, they’ll tell you. McKeon writes, “By capitalizing on women’s anxieties about doing/having/being it all, and simultaneously crafting these neat little pretzel knots of logic, anti-feminists have helped strengthen the silence.”

And speaking of silence, she writes about women denying rape culture and the violence of sexual assault—including the groups of mothers whose sons have been accused of rape and have started a group in support of boys in their sons’ situations, actively trying to convince women that the things that happened to them weren’t even rape after all. (“‘You can make a good faith mistake about whether you were raped,'” Stotland assured me, presumably benevolent, like a fairy godmother of victim blaming.”)

She writes about the rebranding of anti-abortion activists as pro-women as well, and the ways in which their movement is gaining ground, with access to abortion becoming more and more difficult across the United States (and in some parts of Canada, it’s never been great anyway). Is “pro-life feminism” even a thing? McKeon quotes an activist, “The future is pro-life female… We’re not trying to control women or take over their bodies—that’s not it at all… We believe you should have control over your body from the moment it first exists.” McKeon writes that pro-life feminism lacks an agenda beyond being anti-abortion, and that its rhetoric is unlikely to take hold in the feminist movement proper… “But can I see it working alongside the anti-feminist and post-feminist movements to crush modern intersectional feminisms and the reproductive and sexual rights around which they mobilize? Well, yeah, sure, I can see that.”

The book ends on a hopeful note, you will be happy to know. McKeon’s second-last chapter is about young empowered feminists who waging brave and awesome campaigns, both online and in the world. She goes back to high school, where her own feminism was born in a gender studies class, and is inspired and moved by the conversations she sees happening there. The idea that young women don’t care about feminism is a myth up there with “having it all.”

And then she concludes her book with her trip to the Women’s March in Washington on January 21 2017, a monumental event whose media coverage fuelled discord and served the anti-feminist agenda exactly…except the Women’s March was a triumph. The Women’s March was amazing.

“Was the Women’s March on Washington a crucial time for women to join together, or was it an opportunity to confront its historically privileged and narrowly rigid roots?” McKeon asks. The answer is simple. The answer is easy (but it also isn’t). The answer is affirmatively positive: McKeon answers, “Yes. And yes.” And the rest of her book is the reason why she and her reader are so emphatic that this must be the case.

October 23, 2017

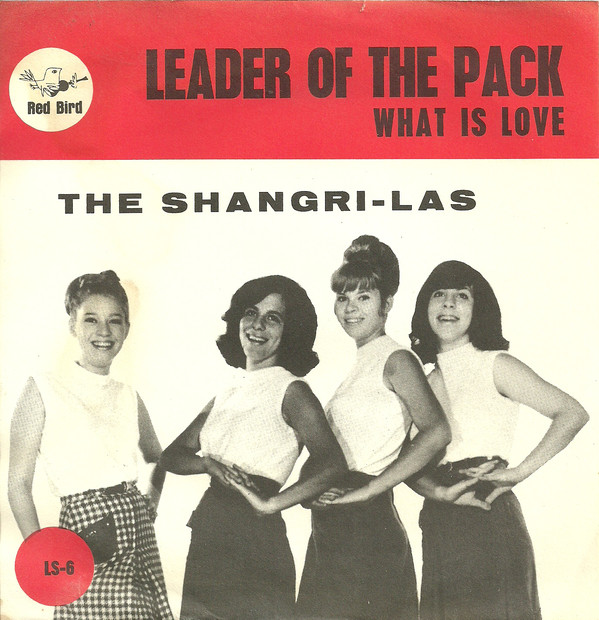

Leader of the Pack Conspiracy Theories

The whole thing just sounds incredibly dodgy to me: “I met him at the candy store,” Betty explains to her friends. “You get the picture?” But no; we don’t. Because what kind of self-respecting motorcyclist, let alone one who rises through the ranks to become the actual leader of the pack hangs around at a candy store? The very idea is embarrassing. What was he buying: Big League Chew? Unless it’s a candy store that’s a front for a pedophile ring, or something else just as sinister.

“Hey, Betty, are those Popeye cigarettes you’re smoking?” “Uh, uh.”

But before we go leaping down “Leader of the Pack” rabbit holes, I want to start at the very beginning, possibly a problem of chronology. Or else the ridiculous insensitivity of Betty’s “friends” who can’t stop talking about her boyfriend and say to her, “Gee, it must be great riding with him. Is he picking up up after school today?” Betty’s reply being negative. Because, obviously, he’s just been killed in a fiery crash, and her friends must have known about this because at school everyone stops and stares when Betty can’t hide the tears, and she doesn’t even care.

Are Betty’s friends just really really cruel and they’re merely toying with her in order to start her crying again? Are Betty’s rampant emotions just a game to them? Although another possibility is that in this era of boyfriends killed in fiery crashes (Teen Angel, Tommy who told Laura he loved her, and the poor fellow who was driving the Jaguar XKE in “Dead Man’s Curve”) Betty’s friends had come to take such incidents for granted, the same way we don’t think a lot about breathing, or gravity, and maybe Betty’s boyfriend’s recent tragic death had simply slipped their minds.

One important clue to the entire song lies in a lyric that follows Betty’s initial exchange with her friends, and after she recalls the way her folks were always putting him down, her friends pretending to play a supportive part by functioning as a literal echo chamber—and let me tell you, tonally speaking, there is something disingenuous about they way they ask her, “Whatcha mean they say he came from the wrong side of town?” Obviously, these girls know their local geography. Betty’s parents aren’t saying anything that Betty’s friends haven’t said amongst themselves. But can you blame them for their disloyalty? I’m not sure we can…

I’ve still not got to the clue yet, but bear with me. All this thinking about the complex and troubling narrative of “Leader of the Pack” has come about because my daughter is obsessed with the song (as I was at her age; it’s a song about boyfriends and candy, which is very appealing to eight-year-olds and a reason why eight-year-olds have a prime demographic of the terrible pop song “My Boy Lollipop” for decades now). And in thinking about “Leader of the Pack” in the context of having a daughter, the line that stands out for me is one that I sang with unawareness for years and years but which terrifies me now, and it is, “They told me he was bad; but I knew he was sad.”

There it is, in a nutshell.

I tell my daughter, “If you ever, ever, hear yourself uttering a line like that, don’t walk but RUN away from whatever relationship you’re in.” Never date someone who is bad but you know he’s really sad. Such knowledge is not actually knowledge at all, but instead it’s a delusion. If he’s really sad, you’re not going to be able to fix him, and then you’re going to have to spend the rest of your life riding sidecar to Melancholy Melvin, who cries all the time and hates your friends. And possibly everyone’s not wrong about him, and he really is bad—this is the Leader of the Pack who hangs out around the candy store, remember. He’s not even good at being Fake James Dean.

So what if Betty’s friends had heard her line about how she knows he’s sad, and decide there’s no other answer…but to mess with the brakes on Jimmy’s bike? Betty’s dad could also have in on the deal, making a point of informing his daughter that she has to find someone new on a day in which the weather forecast called for rain. The slippery streets and the messed up brakes meant that a crash would be inevitable. Though they’d all be also putting Betty at risk—presumably she’d be riding on his bike at some point, and maybe he’d even be picking her up from school that day…

Another suggestion is that Betty herself is responsible for Jimmy’s death, that her testimony about having begged him to go slow was completely a lie. I mean, she hadn’t even ensured that he’d heard her, right? So how earnest could she have been? Maybe the begging was a whisper in her mind. “I could speak this thought aloud,” she told herself, “or I could let him speed and die in a fiery crash, thereby freeing me from the burden of spending the rest of my life hitched to a biker who hangs around candy stores.” Betty’s obvious distress at Jimmy’s passing, as expressed in the song’s final verse, her inability to hide the tears, is mostly because Betty’s feeling guilty, but there is a part of her that also feels freed.

I wonder if the reality is more complicated, however, and doesn’t involve murder in the slightest. What if the entire song is the fantasy of a middle-aged Betty, living in the suburbs during the 1970s. She’s got five kids, one with special needs. Their ranch bungalow needs work and condensation keeps seeping in, fogging up the windows. The kids won’t stop bringing home puppies, and her eldest son is going to be drafted. Betty’s husband Jimmy can’t hold a job for more than a couple of months, and her parents have had to help them out time and time again. Jimmy’s teeth are in terrible shape from decades and decades of eating candy, but they can’t afford the dentist. He has a dream of opening a bike shop, working as a mechanic, but Betty’s lost her faith in Jimmy because his own bike’s been sitting in the carport for years and no matter how much time he spends fixing it, he can’t make the damn thing start. If the bike only started, Betty thinks, maybe her sad sorry husband could ride away, out of their life, and she’d stand a chance at a fresh start on her own.

“Leader of the Pack, and now he’s gone,” is the song’s final refrain, and the meaning is doubled here. First, as a projection, a thought about what could have been if Betty had been able to listen to her dad and break up with Jimmy—but she was already pregnant with their first child by this point, totally craving sugar, and Jimmy always had candy, which kept her coming back for more. What if things had been different, Betty wonders, almost able to see the hypothetical fiery crash in her mind, and hear the thing she might have shouted: “Look out, look out, look out!” Or possibly she wouldn’t have shouted at all. (Also, what was he supposed to be looking out for anyway? So much goes unsaid in this scenario.)

But the refrain is also a more mundane reflection of her 1970s’ reality, about how Betty’s archetypal husband has morphed from a badass biker dude into a sad wreck of a failed mechanic whose white undershirts are stained yellow now and whose leather jacket is in tatters.

“Leader of the Pack, and now he’s gone,” and is he ever, thinks Betty, who is contemplating better things, the return to fashion of shoulder pads, and getting a job as a career gal in the city.

October 20, 2017

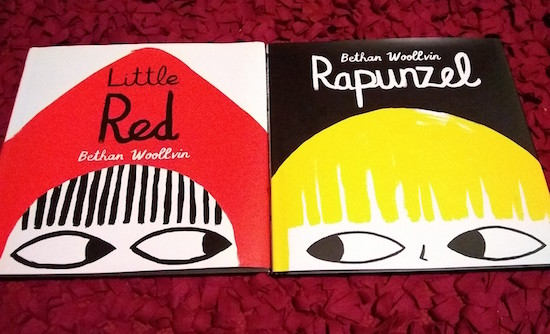

Rapunzel, by Bethan Woollvin

I love me some side eye, the sweet subtle rebellion of a woman who’s got no time for your nonsense. A woman who’s tired of outdated tropes, stereotypes, and sexist cliches. The thing about fairy tales, of course, is that they’re fluid, ever-changing. Even the tired versions of the stories aren’t ever told the same way twice, so one could feel justified in making some adjustments. “[W]hoever makes up the story makes up the world,” Ali Smith writes in her novel, Autumn, and I love that idea. In her first book, Little Red, Bethan Woollvin is making up a world where little girls don’t fall for wolves in bad disguises and get along just fine without the help of a Huntsman, thank you very much. She continues to make such a world in which girls can be their own heroes in Rapunzel, whose heroine rescues herself from the tower and becomes a masked vigilante on horseback—which was clearly a detail that was missing from the original tale. And the very best thing, when you put Little Red and Rapunzel together? The side-eye is solidarity, of course. These two fearless girls are looking right at each other.

October 19, 2017

Mitzi Bytes on the Road

Mitzi Bytes and I hit the road (or at least, we took the train) yesterday to visit with a great group of women in Oshawa, a few of whom had been at the Lakefield Literary Festival this summer, and who had to choose Mitzi Bytes for their book club. I had a really nice time, and not just because it was the best meal I’ve had in ages (with wine to boot), but because the women kept bringing their conversation around to ideas from the book that I find so interesting to think about.

And this weekend, we’re on the road again for the Stratford Writers Festival, where I’m part of the most terrific line-up. I’m giving my blogging workshop on Saturday from 11-12:30, and then at 4:30 I’m on a panel with Scaachi Koul where we’ll be talking about humour and the female experience. I am looking forward to it a lot. And go here for my Q&A with the Stratford folks in which I finally give the goods on just how autobiographical is my novel exactly—a warning, it concerns fire.

October 17, 2017

A far cry from Mr. Stillingfleet’s stuff

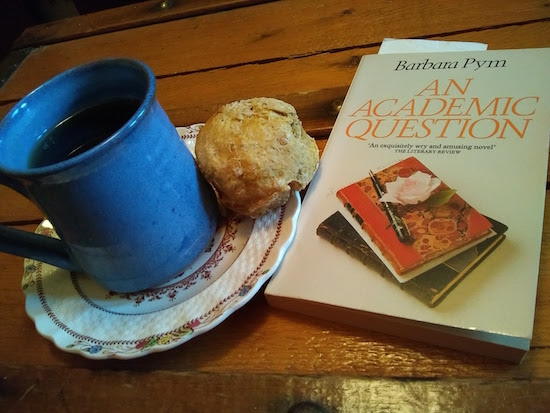

I’ve never been to the Victoria College Book Sale on opening day before, because it’s always on a Thursday and you have to pay $5 to get in, but I hadn’t planned my life well during the weekend the sale was happening last month, and my only chance to go at all would be during the ninety minutes between when the sale kicked off at 2pm and when I had to pick my children up from school at 3:30. So I cobbled together the admission fee, literally out of dimes and nickels from a jar in my kitchen, which made for very heavy pockets, but I got there, and learned of just one distinction between the Victoria College Book Sale on its first day and all the days thereafter: there are Barbara Pym books for sale.

It’s difficult to find used copies of Barbara Pym novels. Her readership was never huge enough, at least not in Canada, as compared to writers like Margaret Drabble, Hilary Mantel and Penelope Lively, whose novels are mainstays at secondhand bookstores (which is the way that I fell in love with all of these writers, and others). I like to think, however, that it’s not just that Pym’s readers are few and far between, but that they’re also quite devoted. The secondhand copies of Barbara Pym novels that I do have came from a house contents sale in my neighbourhood after the death of its elderly owner (which in itself is kind of Pymmish), and that’s the only way I’ll ever be getting rid of Barbara Pym books, by which I mean: over my head body. (I imagine they’re easier to find in secondhand bookshops in England; also, many of her works have brought back into print by Virago Modern Classics with fun cartoonish covers in the last ten years and I’m sure those copies are turning up in charity shops).

Anyway, finding Barbara Pym novels at the Vic Book Sale was exciting enough, but even more remarkable was finding one I hadn’t read yet. I thought I’d read them all, including a collection of her letters and another of unpublished short fiction, and the first book she ever wrote, Crampton Hodnet, which wasn’t published until after her death. I thought I’d spanned the entirety of the Pymosphere, and was content to spend the rest of my life then just rereading her, at least once a summer and maybe even more so, but then there was An Academic Question. I’d missed it altogether. Also published after her death, written during her wilderness years in the early 1970s (before she was “rediscovered” and brought back into print, winning the Booker Prize in 1977 and publishing two more books before her death in 1980).

I started reading An Academic Question on Friday night because I’d been reading A Few Green Leaves (the official newsletter of the Barbara Pym Society) in the bathroom (as you do) and then checked my email to find a reminder that I hadn’t yet renewed my Pym Society membership for 2017. I did so, and took note of the universe conspiring to send me in a Barbara Pym direction, and I’ve already got a backlog of books I have to write about anyway so this would be an excellent opportunity to read for fun and not have to write about it at all.

Take note: I am writing about it. Barbara Pym never fails to incite…

The novel starts off a little roughly. In her note on the text, Hazel Holt writes that it’s cobbled together from two drafts, one in first person and the other in third. Before the book’s spell had taken hold, I kept getting caught on clunky prose and repeated words..but then at some point these problems ceased or else I stopped noticing them. As per Holt’s note, Pym wrote to Philip Larkin of the novel in June 1971: “It was supposed to be a sort of Margaret Drabble effort but of course it hasn’t turned out like that at all.” Which interested me—I remember reading about Pym’s relationship to Drabble’s work in the years when Pym herself wasn’t being published, deemed irrelevant while Drabble herself was very fashionable, her antithesis.

You can see what Pym was up to here—this is a story of a young faculty wife whose sister has had an abortion and lives in London with a man who designs the sets for the news program her husband’s colleagues appear on, all the while the students at the university are going through a period of unrest. In a superficial way, this is Drabble’s milieu—but Pym can’t help but spin it in her own way. It’s the interiority of her protagonist, her doubts and questions, her sense of humour. Caroline is undeniably Pymmish in her preoccupations, spending most of her time with her gay best friend Coco who dotes on his high maintenance mother. While Drabble’s characters are all on the verge of slitting their wrists in a bathtub, Caroline is unfailingly stoic, even at a remove:

‘What was the point of it all?’ Kitty had asked me plaintively, and I felt that for her the evening had been a disappointment, as indeed so many evenings must be now. And what had been the point, really? A few gentle cultured people trying to stand up against the tide of mediocrity that was threatening to swamp them? I who had hardly known anything different could sympathize with their views but for myself I didn’t really listen to the radio; I went about my household tasks, such as they were, absorbed by my own broody thoughts.

And while this is one of Pym’s rare novels that doesn’t contain a single curate, let alone a mention of The Church Times, has only handful of references to jumble sales and the characters drink coffee instead of tea (I KNOW!), the humour is still wryly, undeniably Pymmish. The following passage would never be found in a Margaret Drabble novel:

We sat drinking cups of instant coffee and smoking, commiserating with each other. An unfaithful husband and a dead hedgehog—sorrows not to be compared, you might say, on a different plane altogether. Yet there was hope that Alan would turn to me again while the hedgehog could never come back.

The book wouldn’t work, Pym felt, according to Holt, for its cosiness, and it was remarkable how often the word “cosy” appears in the text (alone with the word “detached”). Which got me thinking about the literary implications of cosiness, as opposed to grittiness, I suppose. Thinking of cosy made me think of rooms, of comfortable sofas, piles of books on the table, interesting items on the mantel—all of which are things that furnish Pym’s books, including this one. Cosy isn’t fashionable, it’s true, what what it is instead is timeless, which might be why we’re reading Pym today while Margaret Drabble’s early novels seem so dated and are out print.

Pym’s Caroline is detached from her life as faculty wife—her husband has proved to be less interesting that she thought he might be, he’s been unfaithful, and she finds herself at a loss as to how support him in his work as one expects she should. She finds motherhood a bit boring and her daughter is cared for by the Swedish au pair anyway. Apart from her friendship with Coco, Caroline doesn’t have anyone to have real conversations with, and when she does talk to Coco, he has no qualms about finding her provincial life kind of tiresome. She spends some time reading to Mr. Stillingfleet, a retired professor at an old people’s home, revealing to her husband that the professor keeps a box of academic papers by his bedside…which ignites her husband’s interest in visiting the frail old man, so he can scoop material from the box and pull an academic coup over his superior. And then Caroline is left with the ethical question of what to do with the stolen paper afterwards, and just where her loyalties lie, and what compromises indeed she is willing to make in the name of her husband’s success…

“‘Hospital romances,’ I said to Dolly that evening when she called around to see us. ‘That’s what I’m reading now. It’s a far cry from Mr. Stillingfleet’s stuff.”

‘Maybe, but it is all life,’ said Dolly in her firmest tone, ‘and no aspect of life is to be despised.”

October 16, 2017

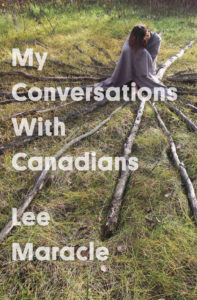

My Conversations With Canadians, by Lee Maracle

Have you ever listened to Lee Maracle speak? I hadn’t, except for a spot on the radio last year where she totally stole the show. Which meant that I kind of knew what I’d be getting into when I went to her presentation at The Word on the Street last month, and she delivered completely. Terrifyingly smart, warm, informed, funny, biting, and not here for any of your shit, was the impression I got from Lee Maracle. I bought her book immediately after the session, the new essay collection My Conversations With Canadians, the latest in BookThug’s Essais non-fiction series. It’s a book born of Maracle’s experiences over the years addressing audience questions at book events, the book’s most central one being from the old man who gets up and asks her, “What are you going to do with us white guys—drive us into the sea?” Never mind Maracle’s formidable response to him, which you’re going to have to read the book to figure out, but I’m still hung up on the man himself, what he stands for. How do you get to be the person with nerve enough to stand up and demand anything of Lee Maracle, is what I’m wondering about, not least because, well, it means that you get to talk instead of Lee Maracle. I don’t have a problem with self-esteem, but I’ve never thought highly enough of myself for that.

Have you ever listened to Lee Maracle speak? I hadn’t, except for a spot on the radio last year where she totally stole the show. Which meant that I kind of knew what I’d be getting into when I went to her presentation at The Word on the Street last month, and she delivered completely. Terrifyingly smart, warm, informed, funny, biting, and not here for any of your shit, was the impression I got from Lee Maracle. I bought her book immediately after the session, the new essay collection My Conversations With Canadians, the latest in BookThug’s Essais non-fiction series. It’s a book born of Maracle’s experiences over the years addressing audience questions at book events, the book’s most central one being from the old man who gets up and asks her, “What are you going to do with us white guys—drive us into the sea?” Never mind Maracle’s formidable response to him, which you’re going to have to read the book to figure out, but I’m still hung up on the man himself, what he stands for. How do you get to be the person with nerve enough to stand up and demand anything of Lee Maracle, is what I’m wondering about, not least because, well, it means that you get to talk instead of Lee Maracle. I don’t have a problem with self-esteem, but I’ve never thought highly enough of myself for that.

Of course, the question I am asking is rhetorical; how do you get to be that guy? And the answer is white supremacy and patriarchy. Which doesn’t absolve me, of course. Which doesn’t place me outside of that audience of Canadians that Maracle is addressing in these essays. Some of which made me uncomfortable, actually—my experience of the world has left me with no understanding of the power of song, for example, which Maracle writes about in her first essay: “we can sing you up to wellness or sing you down to illness, even death. It is the power of our songs. We could even raise our poles with song.” I delineate this to show that even though much of Maracle writes about does not make me uncomfortable—centralizing indigenous experience, issues of cultural appropriation and stealing stories; the necessity of elevating oratory; fiction as a powerful truth—that I understand the experience of someone who might approach the book and its ideas with some hesitancy. Someone who doesn’t know quite yet that the point is to be unsettled after all.

“It is not enough to acknowledge something—you must commit to its continued growth and transformation,” Maracle writes in her essay, “What Do I Call You?” Which is to say that learning and growing is the very point, that being progressive is a process and one you’re never finished with if you’re doing it properly. Which is why welcoming this experience of being unsettled is the very point, along with sitting the fuck down and listening.

I loved this book. I love the way that Maracle peppers her work with allusions to so many incredible Indigenous writers in Canada who are changing the world, sentence by sentence, how My Conversations With Canadians is also the most terrific bibliography. I love how she writes about Indigenous identity, and how Canadian identity is never questioned, or at least not in a non-superficial way. “I am not quite sure how the identity of Indigenous people became fallible and questionable to Canadians, while their own identity is not, but I can say this much: I do not recall ever having doubts about my identity, The point they are making is that my identity is violable—it can be violated.” (Which reminds me of Camille T. Dungy’s comments about her identity as a Black woman: ‘that you see me as a “regular” person suggests that in order to see me as regular some parts of my identity must be nullified. Namely, the parts that aren’t like you.’)

Maracle writes about intersectionality, about feminism, she dismantles the myth of Canadian niceness, and the myth of objectivity too, and then writes about the true myths that are “the path to truth and knowledge”—something science, she writes, is only just beginning to understand. About giving up “the knower’s chair,” which assumes that we as Canadians as the teachers, and Indigenous people our students (i.e. sit down, bellowing old man!). Gender binary and making a link between the idea of binary and that which binds us, an etymological link that had never occurred to me before. A whole chapter is devoted to cultural appropriation, and knowledge and stories as an inheritance which has been stolen from Indigenous children. (Here I’ll repeat something I’ve written before, that until I read Thomas King’s The Inconvenient Indian, I really thought that the theft we talk about in terms of what was taking from Indigenous people was mostly metaphorical. I had no idea…)

She writes, “Rather than looking at where we are in a hierarchical order of things, we should look at our responsibility toward the lives we are dependent upon. In any relationship, we have responsibilities, obligations, and disciplined interaction. We cannot simple do “whatever we want” in the name of freedom.” I also loved this in a following paragraph, “All engagement is a moment of sharing, every morsel of food a moment of sharing from earth to us and back.” In that same essay, “Humility is crucial to recognizing and examining our failures, our mistakes, our contribution to broken relations…” And then she goes on with this brilliance, “Do not mistake my kindness for acceptance of the absence of the right of access to my land or my love for it. Further, do not mistake my kindness for a relinquishment of who I am and who I will always want to be.”

“Settlers ought to look at their history, then look in the mirror. After annihilating our populations, and much of the animal life on this continent and in the oceans, and after spoiling the air, and the waters, who would want to be you?”

Are you unsettled yet?

As I read this book, I kept thinking of the bellowing man asking questions, and that guy had become a stand-in for the kind of Canadian journalist who has made an industry out of writing about Indigenous issues, not so subtly underlining his racism with every click on his keyboard. About how all this focus on colonialism and intergenerational trauma, and de-centreing whiteness, and giving credence to Indigenous forms of knowledge has, well, threatened to destabilize our white supremacist patriarchal society, and for obvious reasons this really bothers this guy. Because of how he refuses not to see himself as central, as neutral, as non-complicit in any of the systems that perpetuate the tragedy of Indigenous people and their communities.

What would happen if he read this book, I wondered. Like actually read, instead of making inflammatory notes in the margins and planning his rebuttals. What if the bellowing old man actual shut up, sat down and listened?

In the words of poet Muriel Rukeyser: perhaps the world would split open.

October 12, 2017

We love Kazoo

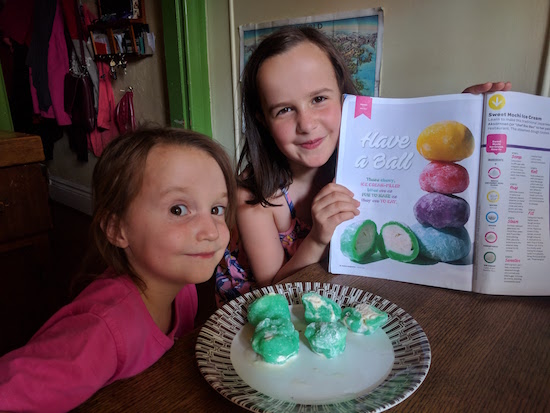

If you have never spent a half hour the night before Garbage Day digging through your enormous recycling bin (which is shared with two other households, one of whom eats a disproportionate amount of pizza, apparently) in search of a missing copy of a children’s magazine that might have been thrown out by accident…then you’ve probably never had a subscription to Kazoo, which described itself as “a magazine for girls who aren’t afraid to make some noise.”

And while I’ve pretty much never liked anything before it was cool (or even after it was, if I’m going to be honest) I’m very proud to say that I was a contributor to the initial Kickstarter for Kazoo six issues ago, and that I’ve never ever been sorry. Even though postal and exchange rates mean I’m paying $70 (CDN) per year for a quarterly magazine—although that might give you a better idea as to why I was digging through the garbage.

Mostly it was because Kazoo is not disposable, which is why I’m happy to pay extra money for something so entirely worth it. A magazine that’s as good as a book, and which is produced so well that it stays in tact after multiple readings. Themes have include Flight, Architecture, Nature, Steampunk, and Music, which all kinds of creative approaches to these ideas, including art, recipes, puzzles, projects, profiles, biographies and more. Each issue includes a comic strip profile of a remarkable woman, and usually these are women of colour, as well as a short story whose writers have included Emma Straub and Jane Yolen, and Meg Wolitzer is forthcoming in the next issue, according to the recent Kickstarter update (and !!!!). Get art lessons from Alison Bechdel, learn to write a song with Ani di Franco, advice on never giving up from Diana Nyad, and read a Q&A with cosmochemist Meenakshi Wadhwa under the headline, “Meet a True Rockstar.

Harriet and I have built a bridge out of marshmallows and toothpicks, we’ve made grapefruit candy and paletas under the guidance of expert cooks, she and her dad made a walking robot out of a toilet paper roll, and our most recent project was mochi ice-cream balls from the Steampunk issue (because we made mochi from rice flour using steam power—get it?).

SPOILER: I eventually found the missing magazine, and it wasn’t in the garbage, but had been put away with a bag of pipe cleaners (of course!). And good thing too, because Kazoo has more than surpassed all my dreams of an amazing magazine to inspire and empower girls, and I’m so glad it’s going strong in its second year. As they report on their website, Kazoo was “nominated for a 2017 National Magazine Award in the category of General Excellence-Special Interest and named one of the “Hottest Launches of 2016” by MIN.” I don’t actually know what MIN is, but I’m sure they’re totally right. I’m looking forward to all the good things ahead, and to renewing our subscription over and over again.

October 10, 2017

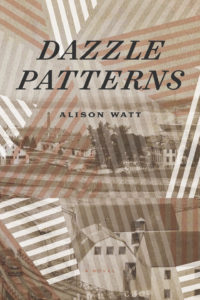

Dazzle Patterns, by Alison Watt

When I’m reading historical fiction, it always takes me a bit of time to get settled in the story, to find my bearings in terms of place and time. It’s like travelling to any land that’s a bit foreign, I suppose, where the customs and language aren’t quite what you’re familiar with. And so I knew to be patient when I started reading Dazzle Patterns, the debut novel by Alison Watt, whose previous works include poetry and award-winning non-fiction. Which wasn’t hard because the premise was compelling: a young woman is working in the local glassworks in Halifax in 1917 as a flaw-checker, dreaming of passage to Europe where her fiancé has been fighting. Parts of the story is also from his point of view, Leo, traumatized after surviving the Battle of Passchendaele, though he doesn’t write that home in his letters. And the other protagonist is Fred Baker, an artisan who works with Clare at the glassworks. He’s the one who delivers to her the hospital on that December day when two ships collide in Halifax Harbour, leading to the explosion that levels huge swathes of the city, leaving so many Haligonians dead or injured. Fred spends the next few days working without ceasing in the overcrowded makeshift morgue, but this doesn’t keep him from falling under suspicion by his colleagues and official authorities—though he’s long been a Canadian citizen, Fred was born in Germany, and there are many people in Halifax who aren’t convinced that the explosion was an accident.

When I’m reading historical fiction, it always takes me a bit of time to get settled in the story, to find my bearings in terms of place and time. It’s like travelling to any land that’s a bit foreign, I suppose, where the customs and language aren’t quite what you’re familiar with. And so I knew to be patient when I started reading Dazzle Patterns, the debut novel by Alison Watt, whose previous works include poetry and award-winning non-fiction. Which wasn’t hard because the premise was compelling: a young woman is working in the local glassworks in Halifax in 1917 as a flaw-checker, dreaming of passage to Europe where her fiancé has been fighting. Parts of the story is also from his point of view, Leo, traumatized after surviving the Battle of Passchendaele, though he doesn’t write that home in his letters. And the other protagonist is Fred Baker, an artisan who works with Clare at the glassworks. He’s the one who delivers to her the hospital on that December day when two ships collide in Halifax Harbour, leading to the explosion that levels huge swathes of the city, leaving so many Haligonians dead or injured. Fred spends the next few days working without ceasing in the overcrowded makeshift morgue, but this doesn’t keep him from falling under suspicion by his colleagues and official authorities—though he’s long been a Canadian citizen, Fred was born in Germany, and there are many people in Halifax who aren’t convinced that the explosion was an accident.

Clare begins to recover from her injuries as Halifax itself slowly rebuilds after the tragedy, and she’s pulled between her parents’ wishes to shelter her and her yearning for independence. When Leo is reported missing, Clare realizes that she’s lost her getaway plan, as well as her fiancé, and contemplates the limits of the future before her. To stay busy as her recovery continues, she begins taking painting lessons at the School of Art, where Fred is also a student. And the connection before them does not occur in cliched ways one might expect, because this is too interesting a story for that, besides there are complications—Clare still loves Leo, and her landlady’s daughter has fallen in love with Fred.

These central strands to the story become woven in a wonderful fashion. The novel’s title comes from the patterns painted onto ships to break up their silhouettes and make the vessels more protected from German U-Boats, which is just one very practical role that artists played in supporting the war effort. Watt portrays other roles as well, artists documenting the war by painting battlefields and the ships in Halifax Harbour, real-life Canadian artists appearing as characters in the book alongside Fred and Clare. The intricacy of glasswork in particular is an important element of the story, glass’s amazing technological capabilities but also its fragility. This is a novel about art, and vision, about seeing, and looking carefully at things—and about what happens when other people fail to do so. The Halifax Explosion and World War One are the book’s backdrop, but not its reason for being—and these historical events aren’t manipulated either to become metaphors to serve the author’s purposes. War and destruction are brutal and violent with long-term ramifications that take years to come to the surface. There is nothing heroic about any of it, except for the people who show up to help others.

And so there would eventually come a point when Dazzle Patterns won me over entirely, as you’ve probably noticed, when its people and the streets they walk on became as vivid as the room I’m sitting in now. I loved this book, the art of its tapestry, all of it leading toward an ending that was absolutely perfect.

October 10, 2017

Where do my books come from?

The other week I posted a photo of my mailbox on a day that was, I’ll admit it, particularly remarkable, but not unprecedented. I get a lot of books in the mail, and the photo received a lot of likes and comments that made me think about a variety of things—where my books come from, what I do with the books I receive from publishers, whether or not I persist with books I’m not enjoying, and other things. These questions are going to be the foundations of this post, and a couple of others to come, but I wanted to start with this, which is a meme I’ve done before involving listing the last books you’ve read most recently and where they came from.

- Saints and Misfits, by S.K. Ali: Received from publisher

- My Conversations with Canadians, by Lee Maracle: Purchased from Publisher’s Booth at Word on the Street

- Dazzle Patterns, by Alison Watt: Received from publisher

- What Happened, by Hillary Rodham Clinton: Purchased from Publisher’s Booth at Word on the Street

- Snacks: A Canadian Food History, by Janis Thiessen: Received from publisher

- Collected Tarts and Other Indelicacies, by Tabatha Southey: Received from publisher

- Once More With Feeling, by Meira Cook: Received from publisher

- Just Jen: Thriving Through Multiple Sclerosis, by Jen Powley: Purchased from Staff Picks shelf at Audreys Books

- If Clara, by Martha Bailey: Received from publisher

- The Mother, by Yvette Edwards: Purchased from A Different Book List

- We All Love the Beautiful Girls, by Joanne Proulx: Purchased from Hunter Street Books

- What is Going to Happen, by Karen Hoffman: Received from publisher

- A Bird on Every Tree, by Carol Bruneau: Received from publisher

- Guidebook to Relative Strangers, by Camille Dungy: Purchased from Parentbooks

- The Misfortune of Marion Palm, by Emily Culliton: Purchased from Happenstance Books and Yarns

- Glass Houses, by Louise Penny: Received from publisher (ARC)

- Today Will Be Different, by Maria Semple: Purchased from Parentbooks last year, this was a reread

- Annie Muktuk and Other Stories, by Norma Dunning: Received from publisher

- The Lesser Bohemians, by Eimear McBride: Purchased from Blue Heron Books

- Pond, by Claire Louise Bennett: Purchased from Parentbooks, this was a reread

- The Murder Stone, by Louise Penny: Found it in cottage library

- Wilde Lake, by Laura Lippman: Purchased from Happenstance Books and Yarn

- Truly, Madly, Guilty, by Lianne Moriarty: Purchased (secondhand) from Beggar’s Bouquet Books

- Scarborough, by Catherine Hernandez: Purchased from Mabel’s Fables

- History of Wolves, by Emily Fridlund: Purchased from Lighthouse Books

- Weaving Water, by Annamarie Beckel: Borrowed from the Toronto Public Library

- Do Not Become Alarmed, by Maile Meloy: Purchased from Curiosity House Books

- Turning, by Jessica J. Lee: Purchased from Curiosity House Books

- The Burning Girl, by Claire Messud: Received from Publisher

- In the Land of the Birdfishes, by Rebecca Silver Slayter: Purchased from Lexicon Books

Results are a little bit skewed because eight of these are books I read on my summer vacation and I tend to more deliberate in those choices, but still. Of the 30 books I read, 11 of them were received from publishers. They tended to be smaller publishers too because a) these are publishers I have relationships with through my work with 49thShelf.com and b) some of these books are harder to find in Ontario bookstores so I am unlikely to come across them on my own steam, at least before review copies arrive. A few are books that I would not have previously sought out of my own. Two of them I read because their publicists were quite emphatic that I, Kerry Clare addressed personally, should do so—nice work publicists; you were right. And when I do read these books publishers send me, I tend to write about them either on my blog or on 49thShelf.com, or in both places.

I tend not to read ARCs because I don’t like them—I liked to read finished books with nice covers and I like to read them when everyone else is reading them.

I also buy a lot of books and am an avid independent bookshop customer.

And finally, I don’t disclose in blog posts if I’ve received a book from a publisher. A lot of bloggers do, and on some blogs that are exclusively review sites, it makes sense. But I don’t think it does for me. I trust myself after ten years that my reviews are not biased because I’ve received a review copy—though this was a learning curve for me for sure but I got over it years ago. I get so many books in the mail, most of which I don’t even read, that the idea of treating these books differently than the books I purchase myself is kind of ridiculous—if anything, these books that find their way to me rather than me seeking them out myself actually get read much more critically, as in, “You better be worth my precious time, Book-I-didn’t-even-ask-for.” I also know that professional reviewers (of which I am one) receive review copies as standard practice and this doesn’t need to be disclosed in their reviews. And finally, I see this blog as a space for me, first and foremost, and that anybody else likes to read it is just gravy, but to pepper my posts with disclosures and the like would undermine the authenticity of what I’m up to here.

October 6, 2017

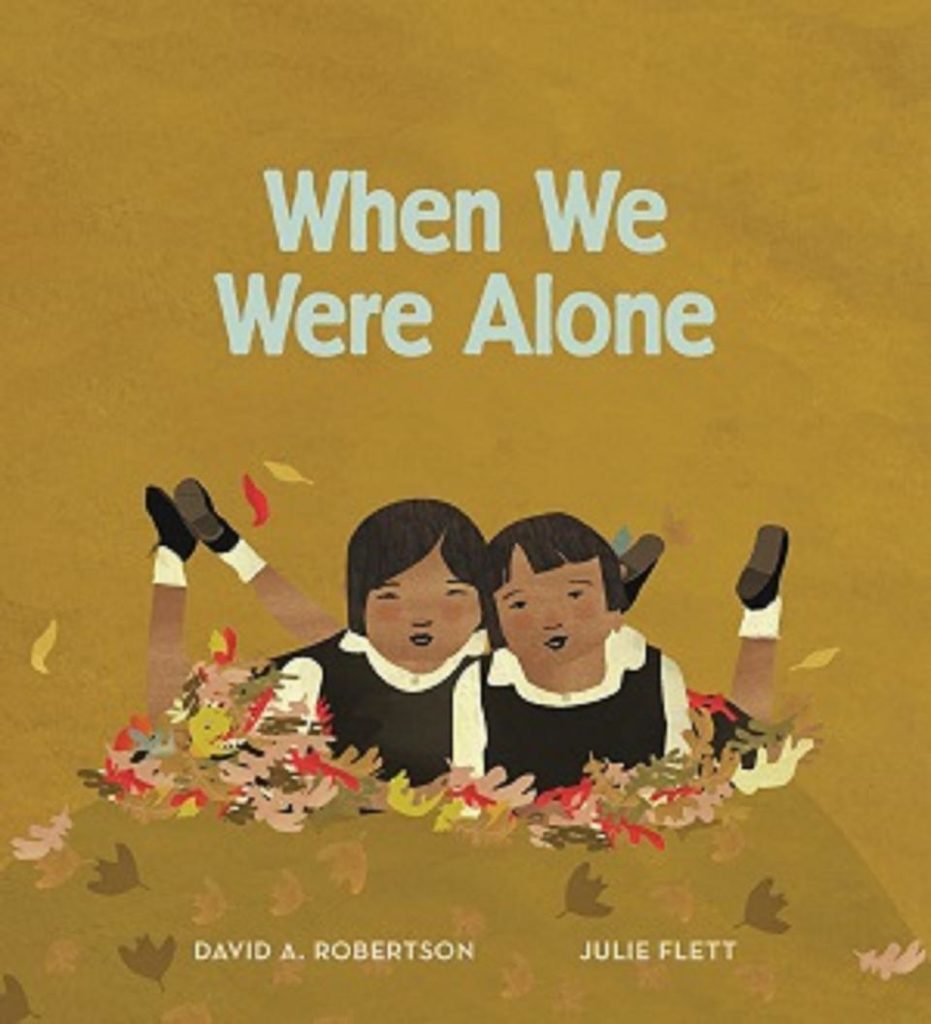

When We Were Alone, by David A. Robertson and Julie Flett

Please forgive the absence of a proper Picture Book Friday post but my phone broke so I can’t take photos, plus my children are off school tomorrow schedules are all askew. But I did make time to run out to Parentbooks this afternoon to pick up a copy of When We Were Alone, by David A. Robertson and illustrated by Julie Flett, whose work I so adore. Partly because Orange Shirt Day was observed at my children’s school last week, and I wanted this book to contextualize it. And also because When We Were Alone has just been nominated for a Governor General’s Award, on the trail of big wins at the Manitoba Book Awards earlier this year and a nomination for the TD Children’s Literature, whose winner will be announced next month. I’d read it earlier this year while we were at the Halifax Central Library, but I didn’t read it to my kids because the book made me a bit nervous. I’d interpreted the title in a sinister fashion, and knew the book was about residential school survivors, and really, I wasn’t sure even I wanted to know what had happened when these poor kids were alone.

But I was wrong, for so many reasons, not least of all in thinking that these kinds of stories were the sort I could ever turn away from when so many other people don’t have that luxury, but also because it was when the children were alone that they were free and used all kinds of smart and beautiful ways to subvert the tyranny and abuse of residential schools. For example, where they had their hair cut short, and dressed in drab uniforms, and were forbidden to speak their languages. But when they were alone, the narrative goes, the children would braid long strands of grass into their regulation short hair, and decorate their bodies with colourful leaves, and hide in the fields far away from everybody else and talk to each other in Cree. So that this is a story of resilience and survival, even more so because the story is told through the perspective of a young girl who is asking her Kokum why she does things the way she does—have her hair so long, wear bright colours, speak in Cree, and Kokum explains that she does all these things because once upon a time she couldn’t.