May 27, 2025

Olive, Again

The tragic news is that my #WinterofStrout is nearly over, and that OLIVE, AGAIN was the last time I got to read an Elizabeth Strout book for the very first time (until whatever she publishes next), and oh my gosh, I loved it. It’s funny because I think reading Strout’s latest book TELL ME EVERYTHING ruined me a bit for my reread of OLIVE KITTERIDGE, leading to me to expect all kinds of things that this book was never going to deliver. But OLIVE, AGAIN is completely a prequel to TELL ME EVERYTHING, a bridge between Olive’s stories and THE BURGESS BOYS and while Lucy Barton doesn’t appear here, I know that Olive will be meeting her soon (and I loved reading about Olive’s friendship with Isabel, whom I met in TELL ME EVERYTHING, and REALLY got to know on my #WinterofStrout when I finally read Strout’s debut, AMY AND ISABELLE).

I also love that I tripped walking up the stairs while holding this book and a mug of turmeric oat milk latte, splattering the top of the book with yellow, the same yellow bursts that are conspicuous throughout the pages of TELL ME EVERYTHING, forsythia and daffodils and everything.

I love the way that Olive grows in this book, or maybe it’s that both she and we get a little bit closer to knowing who she really is. And what she realizes about who she is, which is so different from who she’d been before, is that she really doesn’t know anything at all. “It seemed to her she had never before completely understood how far apart human experience was… She, who always thought that she knew everything that others did not. It just wasn’t true.” It’s a message that I think is so important right now, as so many otherwise kind and thoughtful people dig themselves deeper and deeper into the holes of their convictions.

And the message too that maybe not knowing everything is…fine? A line from the story “Helped,” “‘I think our job—maybe even our duty—is to…bear the burden of the mystery with as much grace as we can.”

May 23, 2025

The Names, by Florence Knapp

I was swept away by Florence Knapp’s novel THE NAMES a book that came on my radar when UK. bookseller Katie Clapham made it her book club pick. I was besotted by the premise: a mother in 1980s’ England walks to the registry office after a giant storm to register the birth of her son, a child is who intended carry the name of his father and his father’s father before him. But the child’s father is a monster, and so the mother makes a last minute switch and gives her baby a name chosen by his older sister. Or else she makes a different switch, and names the child herself. Or else she goes along with the original plan, naming the baby for her abusive husband as she’s expected to do, and the narrative rolls out in three different threads with what transpires with these different choices. The choices not just about the name the boy will carry—we encounter him and his family at seven year intervals throughout the next four decades—but the novel is so much more richly textured than that, being also about everything else that happens around him, especially his father’s responses to the different things the mother has done in choosing the names that she has and the different narratives that are put into motion, oftentimes unstoppable. (This book is tough to read in places. Imagine how many times the average novel might break your heart, and then multiply it by three. OOF.)

The NAMES recalled Kate Atkinson’s LIFE AFTER LIFE, another novel about fate and chance, and flaps of butterfly wings, and about how it’s impossible to ever get life completely right no matter how many opportunities you have to try. This is true especially in the novel’s depiction of domestic violence—there is not a single choice the mother will make that will ever be the right one. But in a more general sense, life is like that for everyone, every good outcome occurring with something else that’s lost, or other unseen consequences. To be in the world at all is only wild and capricious, risky, amazing, and awesome at once.

May 21, 2025

Catch You on the Flip Side, by Lee Kvern

All right, buckle up. Lee Kvern’s Catch You on the Flip Side, whose central setting is a Calgary casino in the early 1980s, begins at a pig farm in the Philippines, where the farmer is recruited for a mysterious mission. From there, we arrive at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, site of the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy in 1968, where Senator Benigno Aquino Jr., Opposition Leader of the Philippines and a threat to authoritarian President Ferdinand Marcos, pays a brief visit before his return to his country from exile, a return that he knows will put him in grave danger. And then we meet a Manila baggage handler who will be in the wrong place at the wrong time, and forced to sneak out of the country, the piece of the puzzle that connects Aquino’s murder to the staff and patrons of the Calgary casino where shady dealings are ongoing and will have ramification for everybody involved for the next 40 years.

I’m a huge fan of Kvern’s work, both its energy and its scope, and I love how I picked up this novel with no idea where it would take me—and how it took me everywhere. There’s audacity in writing a novel about a real life political assassination on the other side of the world, and I love how Kvern pulls it off (and also how much more I know about contemporary Filipino history after reading it). A story this tangled can be disorienting at times (and I wish the book’s production had been more robust—there are several copy edits and messy typesetting that adds to the confusion), but I read it gripped and finished it satisfied. Funny, moving, and epic at once, Catch You on the Flip Side is a standout.

May 20, 2025

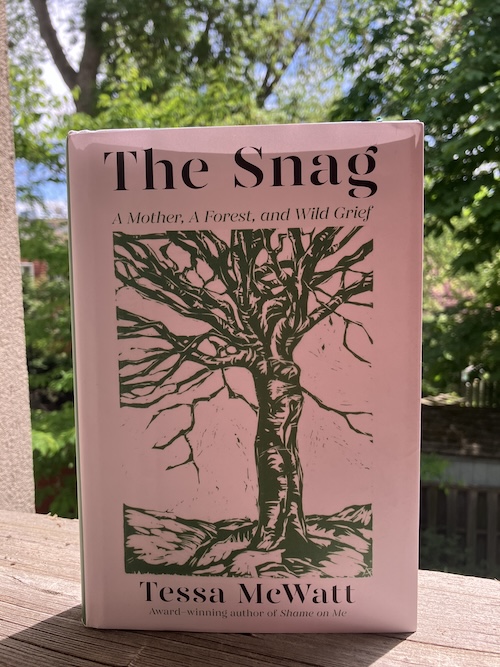

The Snag, by Tessa McWatt

The Snag: A Mother, A Forest, and Wild Grief, by Tessa McWatt, the Guyanese-Canadian writer who lives in England, is a memoir woven of climate grief, the experience of slowly losing an aging parent, and one’s own experience of being in the world. How do we live? And how do we die? Which, of course, is mostly the very same question, and McWatt finds that the answer might lie in forests, and trees. In particular in the trees called “snags,” which are dead trees found in the forest and vital sites for biodiversity, a habitat for all kinds of creatures, and new life and possibilities. McWatt sees an analogy between snags and her own mother, whose dementia is worsening. The book begins on the day that her mother is moving out of her own home, one more uprooting in a life that’s been full of them. It is also, McWatt notes, “the last day of the hottest year in recorded history,” and she recounts a series of the catastrophes wrought by climate change over that year, plus an autumn that so much war and devastation.

“Grief arrives out of rupture. It is evidence of something treasures, now lost. If I sit with this evidence something else will surely come, the way a seed might eventually grow a tree. We are small and hungry and alive.”

Here is the thing that I love about this book, McWatt’s acknowledgement that grief must be sat with, but that also that this sitting is not the end of it. That something can come after this, and it will, but what? And once again, the answer is in the forests and the trees.

The Snag is one of the wisest books I’ve ever read, a memoir about observing, and listening, about music and singing, about the wonders of forests and what we can learn from them about connection and how to care for each other.

“Another world is possible. The extractive, consumptive way we are living demonstrates a severe lack of imagination. But we have the tools, models we use to reclaim, renew, invent. There are communities around the world still rooted, still defending their ecosystems, that are potent sites of resistance. And there are new ones being born.”

May 16, 2025

Encampment, by Maggie Helwig

Maggie Helwig—Toronto poet and novelist, human rights activist, and also Anglican priest at St. Stephen-in-the-Fields in Kensington Market, just a few minutes walk from my house—isn’t preaching to the choir when I pick up her new book, Encampment: Resistance, Grace, and an Unhoused Community. It’s not politically fashionable in the circles in which I travel, but my feelings about homeless encampments have often been complicated and less than generous over the last five years. I know how I’m *supposed* to feel—the “I Support My Neighbours in Tents” signs that others installed on their front lawns signal that direction, but I have a hard time conjuring that support, sustaining it. It works in theory, I guess, but then I show up at the park with my kids and the people living in the tents along its perimeter start screaming at each other and it’s disturbing and frightening. And I have a hard time too with being told that my discomfort doesn’t matter, that my complicated feelings are morally dubious, and that the politics behind any of this are simple, that this is simply a case of rich homeowners versus everybody else, as encampments grow and those of us without our own backyards lose access to public parks and green spaces.

And what I appreciated about Encampment is that there was grace for that, for my complicated feelings and frustrations, just as there is grace for the people screaming in the park, and the people who’ve made their home in the encampment in the St. Stephen’s churchyard over the last few years, and so many others. Maggie Helwig’s capacity for grace is absolutely awe-inspiring, and I read Encampment wishing desperately that the world would give the woman a break. Her own challenges and struggles are woven into the text as well, which underlines just how much she needs a break, but also how her refusal to compartmentalize human experience—that of herself and of others—is where her compassion comes from. Humans are messy and hard. Community is messy and hard. Systems are broken, and what else can we do but try to love one another the best we can?

There is a woman in this book who might be me. (I suspect that, no matter who you are, you will see yourself in many of the people in this book.) That woman is a neighbour who stops Mother Maggie one chaotic day in the parking lot. She’s frustrated by some of the encampment residents, she is afraid of violence, but mostly she is angry because she never wanted to be somebody who turned against vulnerable people. And Helwig writes, “Because it is terrible, and it shouldn’t be like this, and coming up hard against the truth that we live in a society that will dump people like garbage on the side of the road, and there is no good thing we can do, is an awful moment for anyone who hasn’t been through it yet.”

Those of us who live in a world where people are well and housed and healthy and stable have no inkling of what life is like for those beyond those limits, and Encampment rectifies that, explaining away the myths of homelessness, dismissing easy solutions—couldn’t they just…? If only…? The most powerful part of the book for me was when Helwig writes about stuff, possessions: “Maybe this is a good time to talk about the relationship that people have with things, and how far it is really just an inflection of our whole society’s relationship with things.”

And it’s this refusal to see any difference between neighbours, regardless of their housing, that makes Helwig’s voice and vision so extraordinary, and what makes Encampment such a necessary, clarifying, and life-changing read for so many of us right now. Some of the most frightening characters in the book are people with six figure incomes and roofs over their heads, not the guy unconscious in the doorway. Helwig writes, “The true, terrible threat is that, if you just one let these people get too close, you might learn that, underneath it all, we actually are the same. Poor bare forked animals in King Lear’s storm, in a world that’s always ending.”

May 16, 2025

Secret Good Things

Last October, I had a mammogram, and I didn’t tell anybody. Not out of shame, or secrecy, but instead out of a fit of subversion. Because of social media, there is now a template of how we’re supposed to perform these things, maybe a hospital gown selfie, or a waiting room shot, and there’s even a script for how the caption should go, and I just didn’t want anything to do with any of it, and this is how I’m feeling about putting most of my life on the internet these days.

Which is how some people have felt about putting their lives on the internet since the beginning of time, perhaps most wisely, but it’s a departure for me, someone who’s been putting myself out there since I started my first blog 25 years ago this October.

25 years, which is more than half my life, and almost the entire span of the century so far, enough time to know that everything is always changing, whether it’s the internet, the world, or me, and the best thing about my blog is how it has captured all of that movement I might not have noticed otherwise: who on earth was that girl anyway, just post-teenaged, posting angst filled pop culture lyrics on her Diaryland site, which, blessedly, remains only accessible via internet archives if you know where to look? How was the damask wallpaper installed on my Blogspot blog ever considered aesthetically appealing? Who was that lady yammering on about Mommy bloggers before she had kids? Or the one who wrote about how she’d finally got her anxiety under control in a lovely post dated February 2020 (and ha-freaking-HA)?

For a long time, I considered social media to be micro-blogging, and it came naturally to me, I figured, because I’d been blogging for so long. I counselled people about the advantages of living life online—it’s a way of showing your process, making connections, being human, an exercise in authenticity. Which I think was true with blogs, and maybe it still is (blogs are fundamentally obscure; well-known blogger is an oxymoron), and I continue to show up on my blog and be more honest and curious and sometimes messy there, just because of my confidence that almost nobody is reading and so I’m not performing anything.

But it’s different on social media, these platforms underlined as they are by algorithms, the dreams and whims of billionaires, and a tendency to indulge everybody’s worst tendencies.

It was the Black Lives Matter black squares that did me in, back in June 2020. And perhaps this was my old-school blogger ethos showing, but the murder of George Floyd was a occasion that called for extreme thoughtfulness and introspection, work we had to do in our minds and our bodies instead of performing in public by rote, adding a black square to your grid because it was expected. When blogging began, doing what everybody else was doing was anathema to the project, and instead we were supposed to provide our own perspectives, the kind of “take” that no one else could offer, nothing general about it (and not necessarily a “hot” one either).

And it was the pandemic too, the way I felt it necessary on social media to perform my values and politics around everything, which seemed important because the stakes were so high—literally life and death, and preventing our health care system from being extra-overwhelmed, and encouraging the normalization of public health measures—although this compulsion was also a manifestation of my anxiety (amplified by the cacophony of voices I’d encounter online and was desperate to synthesize) as well as an awful lot of pressure to put on one human person (and eventually, that pressure broke my mental health).

I’d long supposed that social media could be an exercise in immediacy, in paying attention, and living in the moment. On Instagram, the insta was the point. I’d also thought that the benefit of a life that looks cool on Instagram is that you end up with a vase of tulips on your kitchen table and delicious meals at a good restaurant that you get to eat once a photo is taken. The pressure to show up on social media can push us out into the world, make us try new things, and go to new places, and I’ve been selling myself this idea for a long time, but for me—on social media at least—it eventually ceased to be wholly true.

It was when I would be someplace beautiful and thinking more about how great it would look on Instagram than actually being there that it began to feel icky. Or if I’d failed to get a good shot, or had no photo at all, and it seemed like the moment had been wasted. The overwhelming pressure I’d feel to include a record of everywhere I went, and everything I ate, and everyone I saw, because otherwise, it was like none of these things had even happened. And I’m going to say that I experienced some of these same pressures back when I was avidly scrapbooking my teen years before the internet even existed for me. Possibly this is a ME problem, instead of a problem in general, but it definitely was a problem, and a habit that I had no idea how to break.

Contrary to what I’m saying here, I actually have good boundaries when it comes to the internet. When I go on vacation, I never look for a wi-fi password. My phone goes to bed a couple of hours before I do every night. I don’t have a good data plan, so I don’t have access to the internet much of the time when I’m out in the world, and these are choices I make most consciously. But it was still not enough , and I’d have to push it further. I was tired of feeling divorced from the moment, and as though I were living my life for an audience. Authenticity is a fine thing, but I was feeling as though I were constantly submitting to scrutiny. I was also exhausted by a politics that was demanding this or that, us or them, just a further entrenchment of divides that were already so dangerous. This was around the time I started adding “avid human” to all my online bios, instead of a series of hashtags. It was an assertion that I, like you, contain multitudes, and that the work I do in my own head and in my own community might be far more important than anything I happen to be inputting into the billionaires’ algorithm machines (substack included!).

This post I wrote at the beginning of 2024 was the beginning: “In 2024, I want to be more thoughtful…and keep more things—more the joy and the pain—just for me, and the people in my life.” Slowly, slowly, I made progress. At the end of the year, I’d removed Instagram from my phone.1 I’d kept my mammogram private, just to prove this was possible.2 I performed good deeds and people did nice things for me, and it all happened even without being broadcast. I went out for dinners that you don’t even know about. Sometimes I was happy or I was sad, but you didn’t hear about it. Other times, the sunlight fell on my table in such a way, but the point was to notice it, not to hold it. I can read a book and not follow with any kind of response, if I don’t feel like one. I’ve not posted a somewhat unflattering selfie of me in a swim cap for months now, even though I go swimming every day. I went to see the cherry blossoms at Robarts Library, and only posted a photo four days later—which in cherry blossom time is actually 760 years.

I keep thinking about Shawna Lemay’s 2020 post, “Do Secret Good Things,” and what it feels like to have some tricks up my sleeve, instead of letting it all hang out there for everybody to see. I’ve become more comfortable with not controlling the narrative, or even (and more importantly) feeling I have to. Moments happen, and I let them (I say, as though I have any power otherwise). And I’m feeling so much better for it.

The danger of this, of course, being that now I’m just performing my cessation of performance, that this is more of the same, that I’m as show-offy and self-satisfied as I ever was. I don’t think I am (I waited this long to tell you about my mammogram—surely that stands for something), but I don’t know, and maybe that’s the point.

I don’t know, and I don’t even have to.

(This piece first appeared in my Enthusiasms newsletter, which is the Pickle Me This Digest. If you’d like to receive a copy of my newsletter in your inbox every month, you can sign up here!)

May 13, 2025

Favourite Daughter, by Morgan Dick

No one’s got their shit together in Morgan Dick’s debut novel, FAVOURITE DAUGHTER, the story of two women who share a father but who’ve never met each other. When her estranged dad dies, Mickey learns that she’s to inherit his estate with one proviso: she must complete seven sessions of therapy. And when she walks into the therapist’s office, it’s Arlo she encounters, her father’s other daughter, each woman with no idea who the other one really is, or that they have a connection at all. Which means that Arlo is technically violating no ethical guidelines as she takes on her sister as her patient, but maybe there is something to the sibling dynamic and boundaries have never been Arlo’s strong point anyway, years of trying to save her alcoholic and disappointing father leaving her prone to becoming tangled up in other people’s messes, and soon the siblings are as complicatedly invested in each other as true siblings can be.

Although even without the genetic connection, Mickey would be a formidable challenge to a therapist. The centre of her world is her job as a kindergarten teacher, a job that gives her life shape and meaning—she’s been cut off by her mother, and doesn’t have any friends—but a bad call on the job and the fact of her drinking means that Mickey’s job might be taken away from her forever. After years of addiction, can Mickey finally make meaningful change in her life? And how different is she from Arlo anyway, who appears put together on the surface but whose security is just as fragile as Mickey’s is, and who has made her own mistakes? Or the very slutty lawyer, Tom, who’s settling their father’s estate, or their long-suffering mothers, or Mickey’s very weird neighbour with the luxury cat?

Each of them is a complete and utter mess, and yet also sparkling with some goodness, and wholly worthy of love, which is the charm of this novel, which is sometimes sad, sometimes deadpan, and ever surprising.

May 7, 2025

A Mouth Full of Salt, by Reem Gaafar

Reem Gaafar’s debut novel, A Mouth Full of Salt, 2023 winner of the Island Prize for a debut novel from Africa (and the first book by a Sudanese writer to be recognized by the prize) grips the reader from its opening line, “Until a body was actually found, they referred to him as ‘missing.'” The body in question is that of a young boy presumed drowned in the Nile, a too frequent incident among the people from his village: “The Nile was a trap that attracted, ensnared, and buried all at once. It took from them as much as it gave.” Which what happened to Fatima’s brother after all, years earlier, a tragedy from which her mother has never recovered, leaving her a little outside the local community of woman, and this Fatima can relate to. She too is also set apart from her peers, although this is by her determination to pursue her education, as opposed to her good friend Sawsan, whose wedding is approaching.

A Mouth Full of Salt moves between Fatima’s perspective and that of Sulafa, the mother of the missing boy, whose been relegated in her household after her failure to have more children, and whose husband’s second wife is currently pregnant with twins. As the villagers keep watch for the boy’s body to resurface, other catastrophes beset the village one-by-one: farm animals are struck by an illness, and die on mass; fires take down gardens and orchards. Villagers are talking about prophecies, worry about a curse, and soon that something has gone very wrong for these people are altogether undeniable.

Like Sudan itself, this novel is cut in two, and in its second half, readers begin to understand how the nation’s history is at the root of what’s happening in the village. From the 1990s, we’re taken back to 1943 and to Nyamakeem, from the country’s south, who has fallen in love with Hassan, a northerner, an Arab. Such unions are rare and frowned upon, and Hassan is rejected by his family. The two of them attempt to build a life together in Khartoum all the same, raising their son, but when Hassan eventually stops coming home to them, Nyamakeem has no choice but to go back to his home village and his family to find out what happened.

How the lives of the women in this novel intersect is the crux of a taut and measured story. Gaafar, who now lives in Ontario, and is also a physician, has crafted a beautiful and compelling novel about women attempting to break free from the limits of their power.

May 6, 2025

Gleanings

- Yesterday, enroute to the opera, we paused on the walkway leading off the ferry to watch 3 seals sunning themselves on rocks. It was a low tide. The ferry was right on time. On the muddy shore, a pair of geese with their goslings dozed at the edge of the water.

- It’s not just about choosing between glass half empty and glass half full perspectives: I think it really matters that we not turn our grimmest anecdata into the dominant narrative.

- My kink is making salad dressing with the last of the mustard in the jar, or a cup of tea in the jar to use up the dregs of the honey. These are small but satisfying actions, that ensure precious resources literally don’t go down the drain.

- The fringe tree and wisteria –– les pièces de résistance –– are the last to awaken, with a spectacle of long white streamers and violet blooms so beautiful that it’s a wonder we’re in Toronto and not Monet’s garden. The only thing now left are the anemones, and they won’t appear until late Summer when the whole garden is so verdant and alive that it’s hard to imagine that all of this beauty was ever underground. I watch it all unfold like a piece of music that gradually thickens and intensifies as instruments enter one by one.

- The digital sphere is horizontal, when what people crave is the vertical or deep engagement. As artists we are all about the vertical. I can’t help but think about how we all keep being fed this stuff we don’t really want.

- I met a friend on the way in (a friend from the outside world, not the pool) who told me that the pool wasn’t too crowded, and her beautiful child told me that water was great, and they were both right.

- This isn’t a story about church. Heaven knows, I’m not the one to tell that story, at least not today. This is a story, maybe, about grief and love. About life, and death, which, I suppose, is really what all stories are about.

- “To what purpose?” It’s probably just a fancy way to say “why??” but it has the advantage of *feeling* new. So when I find myself NOT throwing something away (like instructions for something we no longer own), I ask myself this question. And when the answer is “for collage or another art project” I ask again, for a couple of reasons. First, “interesting” instructions appear with some regularity, so all I have to do is either wait or check the recycle bin. And second, I haven’t made a collage since the pandemic lockdowns.

- While I’m always excited to read Lindsay’s work, I’m especially intrigued by this particular book, as it deals with a dynamic that hits close to home—the challenge of trying to make art while navigating the foggy, panicked, exhausting days of early motherhood. Though my kids are older now, and finding the time and energy to write no longer feels quite so impossible, the difficulties of balancing creative and care work never totally go away

- I only cried once, but it was almost from happiness. Or maybe it was from sadness. Or maybe both. The thing about grief, made visible, is that it’s made up of all the things a human can feel.

- My almost-might-have-been-brilliant career foundered on the dreaded shoals of non-confidence, from within and without. I cannot tell you how many times my manuscripts have apparently gone missing in large Ontario publishing houses. I am the freaking Queen of the Lost Manuscripts. This is not a business for the faint of heart or thin of hide and by then, I possessed both. What, I ask, would Pierre Berton do?

- On this spring morning in Wheatley, with the woods flush with snow-white Trilliums beginning to bloom, the park looked and smelled like hope and joy to me.

- I feel strongly that we can’t solve gendered polarization online. The online world is a tricky place for all of us, on the left or right, because we are unable and unwilling to step into the one another’s spheres, and what we see from the “other side” often entrenches us even further in our beliefs.

- The bear is a bear; the bear is Grendel, embodiment of our oldest and deepest fears; the bear is cancer; the bear is nature. They are all, in their own way, wild – and the wilderness is not somewhere else, separate, held back or “conserved” within inside the arbitrary boundaries of a park.

May 5, 2025

The Cost of a Hostage, by Iona Whishaw

For the last few years, I’ve looked forward to a new Lane Winslow mystery novel in the spring like I’ve looked worked to forsythia blooms and cherry blossoms, and just like spring herself, author Iona Whishaw has never failed me. The Cost of a Hostage is the twelfth instalment in her series about the brilliant polyglot whose wits are only matched by her beauty and whose desire for a quiet life in the small community of Kings Cove, outside Nelson, BC, is thwarted by her tendency to stumble upon dead bodies and wander into crimes in progress. Thankfully, however, nobody is better equipped to solve these crimes, much to the chagrin of local Police Inspector Frederick Darling, who eventually becomes Lane’s husband. Which means he often finds himself in fixes like the one that kicks of this latest novel: Darling’s brother has gone missing in Mexico, and has perhaps been kidnapped; is there any possibility that Darling can get to Mexico without convincing his dear wife that she’ll be just fine staying at home? The answer is, of course, no, and so off they go, which Darling is not exactly sorry for. Lane Winslow is surprisingly useful to have around, and besides he likes her company. Their marriage is a rare and beautiful thing in the late 1940s, an arrangement of equality, both partners ardent in their admiration and respect for each other’s keen intelligence (though Darling would admit that Lane’s is the keener one).

Anyway, staying home might not have been so quiet either, after all. When a small boy is kidnapped in Nelson, the circumstances are curious, and Ames and Terrell, running the Nelson Police Department in their boss’s absence, have their hands full solving the crime, especially once their chief suspects turns up dead in the local ferry’s paddle-wheel.

Once again, Whishaw brings her readers a story with fascinating moral complexity and a healthy dose of feminism and progressive values. And yes, just enough peril that you’ll be totally gripped.