June 30, 2020

Gleanings

- We white people, who have the privilege of not being treated badly for our skin color, are being called to create new stories for everyone.

- The work I’m doing is my business and I have to think hard—constantly — about how to effect change and uphold my values

- Strawberries pretty much steal the show…

- “Oh my god,” I thought to myself in shock, “what am I doing? I don’t even know this guy and in just a few hours I’m going to marry him!”

- But watching these clouds parade across the sky, was a ritual which brought into my body, through my eyes, a sense of possibility as endless as that blue sky….

- So anyway, that’s me and masks and I’m just going to have to embrace it like everyone else.

- Writing is not the only work.

- I am never quick to clear plates, because I find this stage of a meal thoroughly satisfying.

- Six nags and mottos to embroider, when I master the satin stitch.

- Cruel systems surround us. Unless we’re cut by them, we can stay blissfully unaware.

- There is a specific kind of rain that warms my cockles. It’s the steady, light as the wing of a hummingbird, and flows in a gentle, easy way.

- You never knew, eavesdropping on Mildred’s stories, what you might hear, but it was guaranteed to be good.

- If, during these sheltering at home times, you’re lucky enough to have a garden, I’ll bet you’re embracing it.

- Swimming this morning, I wondered, where does the word “lake” come from?

- The chamomile is posing against the black currants that I’m looking forward to.

- I really admire Vivian Maier’s photographs, in particular her black and white self-portraits.

- The thing about posting photos of yourself through time, is that you really begin seeing yourself, and seeing yourself differently.

A handful of posts here are from writers who took part in my June blogging experience. They have been amazing. My next course offering is coming in September, and registration is open now.

June 26, 2020

Our Job is to Hear Them

I have been thinking a lot about how those of us who are white people can continue to have conversations about race, but also about how “conversations about race” isn’t most effective when it’s just us yelling at other white people. And this is not to say that white people don’t need to be yelled at, BUT I am not sure the white people in my feed are necessarily those who most benefit from the “Things to Stop Saying to Black People” memes that begin with, “Quit asking us if we twerk.” I have never asked anyone if they twerk. I don’t know what twerking is.

But those of us with social skills enough to, say, know not to touch people’s hair, still have thinking to do, racist biases to unpack. Which is why I keep clicking on these memes, because I want to do this work, to figure these things out. But I think that memes are not going to be where the answers are found, and that original thinking (and learning) is required instead.

And so I want to write about what I’ve learned and am still learning about listening, and about how listening is more important than understanding. (“But you see, Meg, just because we don’t understand doesn’t mean the explanation doesn’t exist.”) For a long time, my friend would talk about how conspicuous he felt as a person of colour in my hometown—and I just assumed he was being sensitive. I used to hear stories of racism, and assume there must be more to the story, because things like that don’t just happen. And then one day another friend told me that her son was being teased for the colour of his skin, and I replied, “But that doesn’t make sense.” Because so many kids in the class were people of colour, was what I meant. And she gave me this look, a look that turned my world around. In that look I saw the fact that I have no idea, and that to define my understanding of the world by the limits of my own experience is such a fallacy, that it’s ignorance. And who would want to live in the world like that?

I will tell you that when I heard about the death of Regis Korchinski-Paquet, killed when police arrived at her apartment during a mental health episode here in Toronto, I was unsure what role the police had played in her death, figuring it must have been an accident. Because “things like that don’t just happen.” But of course this is when the world was still reeling from the murder of George Floyd, killed when a police officer knelt on his neck for nine minutes. And if we hadn’t seen a video of that, would anyone have believed it?

But of course, plenty of people would have believed, their life experience having established that police brutality is an unremarkable fact of life instead of an aberration. And those of us who have remained ignorant? It’s only because we weren’t listening, because certain voices matter more than others, because we’ve been so invested in the status quo, in our comfort, that we’ve failed to read the world.

So what now? Because the point is never to be one’s own awakening. The point is what we do with our knowledge, with our power. Voice your solidarity with Black Lives Matter. Call your mayor and city councillor and demand police defunding. Support Black-led businesses and organizations. Keep learning, keep reading. (I recommend Jesmyn Ward’s Men We Reaped, and Desmond Cole’s The Skin We’re In.)

Keep listening.

The stories are there. Our job is to hear them.

June 26, 2020

Five Little Indians, by Michelle Good

‘Lucy leaned back in her chair, hands folded in her lap. “They call us survivors.” “Yeah.” “I don’t think I survived. Do you?”‘

Cree writer Michelle Good’s debut novel, Five Little Indians—winner of the HarperCollins UBC Prize for Best New Fiction, Good earning her MFA at UBC while also practising as a lawyer—is the story of five Indigenous young people who were taken from their families as children and grew up at a remote church-run residential school where they were subject to abuse and deprivation, and then cast back out into the world with nothing as they came of age—with no skills, no community or ancestral ties. Nothing but trauma, and then what happens next? And the novel is the answer to that question.

Set in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside during the 1960s and decades that follow, Five Little Indians weaves together the stories of Kenny (once notorious for his escapes from the school, a pattern that continues), Maisie (a mother figure for the others, but unable to comfort herself), Lucy (who finds meaning in motherhood), Clara (who finds herself in the American Indian Movement and connecting with the teachings of an elder), and Howie (who struggles to stay out of jail).

The first 100 pages are hard-going, not just because of the trauma they convey, but because the reader is still getting a sense of novel’s structure and the characters themselves too seem to be finding themselves, their feet, and are not as developed as they’ll be in the rest of the book. I will admit that I was wary during these pages that this would be a novel that worked for me, but I am so glad I kept going. Because when Clara’s character takes her turn telling the story, all at once the novel is injected with a furious momentum and energy, the writing in these chapters so artful and confident, and it charges the remainder of the book with narrative magic. And we see that these characters find ways to support each other, to save themselves, to keep going and try to survive and thrive. And sometimes they succeed, and sometimes they don’t.

The point of a book with five protagonists is that there is never just one story, or maybe that one story turns into a different story for every kind of person. This novel also complicates the idea of survival, which is more meaningful in theory than practice, a process that never ends, and which can be impossible. Many of us readers like tidy endings, a story of healing, resolution, but for those who carry the traumatic legacy of residential schools, there is often no such thing. Because how does one reconcile the irreconcilable?

But the end of the book, these characters were firmly lodged in my head, their voices, their connections, their pain and their joys. Powerful and deeply felt, Five Little Indians is both a good read and a literary achievement.

June 25, 2020

A Good Day

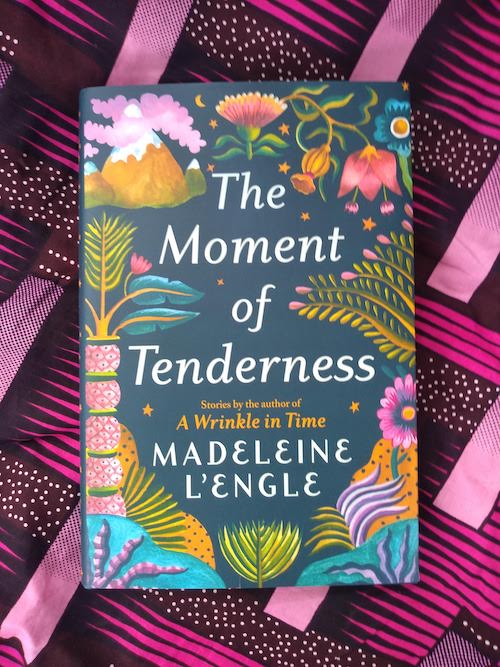

Yesterday I turned 41, and had the most excellent day. I’d asked for a gorgeous dress from Zuri and a new collection of unpublished short fiction by Madeleine L’Engle that was displayed in the window of the sci-fi/fantasy bookshop around the corner from my house, and the aesthetic effect of my gifts is so absolutely stunning, not to mention I’m wearing the dress right now and I love it, and the book is terrific—I am halfway through already.

The other remarkable thing about yesterday is that I went on the subway (and a bus) for the first time in months to pick up a car rental. (We usually use a carshare company which is much more convenient, but it’s still not reopened.) Transit was unremarkable really, the subway pretty empty, the bus not crowded either. And then I had a car and we all drove to the beach, and that the weather was blustery and we were wearing sweaters didn’t bother me in the slightest, because I’d rather be warm than roasting, and the clouds were so delightfully moody, the sky an ever-changing scene.

We had tea and scones, and kids got buried in sand, and they looked for cool rocks, and we collected sea glass, and chilled our bones by wading. Later we walked up to Queen Street, the restaurant patios on their first day of reopening, which meant we could get the lunch we wanted, though we ate it takeout in the park, and went back down to the beach to collect more sea glass and get ice cream cones, and it was the most extraordinary ordinary kind of day, and I feel so very lucky.

June 23, 2020

Gleanings

- People’s relationships with their dads are on such a huge spectrum, and they are both complicated and simple.

- And like Lionel Shriver delivering a keynote in a Sombrero, every beat of his book twanged false.

- it was so very wonderful to gather some of our silent book club friends to finally, companionably, utterly luxuriously enjoy our reading on the grass, in the gorgeous shade, in each other’s bookish company once again.

- From him I learned …that when things are especially crummy you should be very pleased because there’s nowhere to go but up and that the patio in a summer rain is a fine place to dance.

- Because for me, how I walk through the world is the thing. This is what living is.

- It’s late in human history. Is it too late? You can’t say.

Do you like reading good things online and want to make sure you don’t miss a “Gleanings” post? Then sign up to receive “Gleanings” delivered to your inbox each week(ish). And if you’ve read something excellent that you think we ought to check out, share the link in a comment below.

June 22, 2020

The Gift of June

There has been a resurgence of joy lately, ridiculous in its excess. On Friday night we came upon a giant inflatable unicorn on the road, is the kind of thing I’m talking about. Picnics with friends, cake in the park, little kids on bicycles furiously pedalling, and it’s hot, but we bought an eight foot round pool for our backyard, and the happiness the pool gives me, that pool blue, and beach towels hung over the railing. A bowl of cherries. Sheets on the line. Life itself meeting my standards for delight, which is not such a tall order, really. All these hard months as we’ve been thinking about learning to appreciate the little things, so much of what we’ll never take for granted again—but I never took any of it for granted ever, I would indignantly protest inside my frightened mind. I loved every single bit of it, which was why it hurt so hard to lose it, the life I made, the patterns of the days. Never once have I failed to appreciate how the light falls on Major Street at 9:15am, the blossom detritus on the sidewalk. But it feels like the world is returning again, and it’s never seemed more glorious.

June 18, 2020

We Can’t Let Our Imaginations Fail Us

It was interesting to read Oliver Burkeman’s Guardian column in May about expecting the worst in general and in particular during our current crisis. It was interesting, because I am usually pathologically inclined to hope for the best (albeit wisely—it’s a pack an umbrella just in case, kind of thing) and I get frustrated by doomsaying, because I feel like it’s a self-fulfilling prophecy. But doomsaying and hoping for the best, so says Burkeman, are actually two sides of the same coin. Both are actions performed by people “engaging in their own private methods for managing their emotions.” And for the most part neither action has bearing on the future, because the one thing we all have in common is that nobody knows.

But I am not completely sure, at least not in the case of moment in which we find ourselves. Sometimes I feel like there is something craven in pessimism, or maybe it’s not that it’s craven so much as a failure of imagination, to be so adamant that things could not possibly ever be okay. Though as Burkeman writes, there is actually safety in imagining the worst possibilities, “as bad as things can get” as close as one might manage in uncertainty to a kind of solid ground.

And yes, of course it’s a failure too to imagine that things couldn’t possibly get worse, or more terrible, but here’s the thing: if things are going to get worse, they will, whether you imagine it or not. Whereas for building a better world and more possibilities, imagination is essential. Imagining ways to restructure societies so that racialized people are safe, for example, and the disproportionate funding of police forces is reallocated to social services instead. Imagining ways that schools and workplaces can function and keep people healthy and connected, or how outdoor parks and pools could reopen this summer and people can enjoy these amenities safely, or even how we can all keep going and working together as Covid outbreaks continue to happen, which they will, instead of throwing our hands up and screaming, “Second wave!” and taking up permanent residence under our beds.

There is optimism, and there is wilful ignorance, and they’re not necessarily the same. At the beginning of the pandemic too I was as doomy as anyone, because something was coming and no one knew what it was, and I wanted to be safe, for my family to be safe, for vulnerable people in our community to be safe. And because so many of us took precautions at that moment, which was a big sacrifice for all kinds of people (not me; I’ve been sitting at home eating gourmet cheese and keeping comfortable), things turned out to not be so bad after all. Not good by any means, but certainly good in comparison to the carnage in so many regions. I was thinking I was about to become a character in Station Eleven, is what I mean, and probably a dead one, but it didn’t turn out to be like that. Infection rates are going down in Ontario. We have reasons to be hopeful.

Which is not to say we’re about to pack hundreds of bodies into a crowded space anytime soon. Guys, we’re not Florida. And I think that many people in Canada are confused about this, sharing memes from Americans who are scared shitless, and for good reason, because culture warriors have decided to declare that an actual virus does not exist. “We’re right back where we started!” those memes keep on screaming, and they’re not wrong, but that’s because many communities have not done what’s happening here in Canada, in Ontario. (What’s happening here in Ontario is not exactly exemplary either. Testing and contact tracing have lagged. There has been a failure of imagination on that end, and also competence, but it hasn’t been an abject disaster. The answer, as always, is somewhere in the middle…)

We’re not right back where we started because people are wearing masks now, avoiding large crowds, shops have built plastic barriers and have caps on customers, people aren’t commuting en mass, offices aren’t packed with workers, we’re not sitting in doctor’s waiting rooms. This is not square one, where we are—though that risk remains for racialized communities, for people in dangerous working conditions, working in food production in particular, should not make those of us who are safer complacent. But it also means that we know a lot more about how and where the virus is spread than we did in March when we were all in such a panic and the reports that were coming out of Italy were devastating. We’re so much further down the road.

And no, I don’t think the pandemic is over, as many people keep accusing others of believing, but I do think we have to imagine a way to move forward and live with the virus. And I am trying not to get too frustrated at the sight of young people congregating in backyards, not so distanced at all, or the families who have continued to have playdates all along, because the likelihood of harm is really quite low in practical terms, which is kind of annoying for everyone who has been so strictly following the rules, it’s true, because we’d like to see a kind of justice, right? I know there were people who were disappointed that there was no documented Covid spike following an epic gathering of people in their 20s at a Toronto park in May. Because it would have felt good to be able to point to those people and say, Serves you right, and even have somebody to blame for part this bad dream we’re collectively living through. Much better than so much being random and shitty, nobody to point at at all.

(There have been spikes of illness at people in their 20s in general, however, and I wonder how much of this is tied to young people tending to be employed in high risk workplaces, living with roommates, all plans derailed, and if the backyard parties are necessary because of how much shittier the pandemic has been for them than those of us who are more comfortable and established…)

But there aren’t rules. I’ve written about this before. Everybody’s using their best judgment as we venture together into the unknown, and yes, many people’s best judgment is terrible. But many people are doing just fine, and want to stay safe, and protect their communities, and return to their businesses, and socialize with families and friends, and support their favourite restaurant, and have a localish summer holiday, and take precautions to stop the spread of the virus, wearing masks, washing hands, keeping distance, and I guess what I mean is that I wish amongst the various catastrophic outcomes so many people are imagining is the possibility that we might also be fine.

June 17, 2020

The Last Goldfish and In the Shade

“Good reviews…prompt me to borrow a recently-published book on grief from the library. I read the acknowledgements, glance at the author’s photo, and skim the table of contents. Partner, child, parent. Not a word about friends, which causes me to toss it onto the pile of books on my night table.” —Marg Heidebrecht, In the Shade

Thankfully, there is no reason related to my own life for me to pick up two books on friendship and grief, except that they’ve both come out this spring, and also friendship has been on my mind of late. Back in March, it was telephone calls to my closest friends that brought me solace in moments of stress, and my two best friends from high school in particular, friendships whose foundations were born on the telephone, long and pointless conversation, spiral cords wrapped around our fingers, until our parents would finally get on the line, and yell at us to get off.

It’s these connections that Anita Lahey conjures in her new memoir, The Last Goldfish, a monument to friendship and to her friend Louisa who died of cancer when they were 22. A friendship that begin in Grade 9 French class, and persisted through high school in the early 1990s, one’s teen years enriched with so much possibility because of friends, the doors they open for us. For Lahey, Louisa was it, a sparkly personality, with divorced parents who didn’t go to church. But soon their families were each other’s, and they would both go off to university together in Toronto, living together in a co-op dorm at Ryerson, studying journalism. Dealing with other roommates, boyfriends, school and family drama, and also Louisa’s health problems, which would stay in the background for many years, numerous lumps removed from different parts of her body from childhood. Until finally she is diagnosed with cancer, and Lahey continues to be part of her friend’s life, keeping her company during hospital stays and treatments, the hospitals just a stone’s throw away from where they lived and worked, and life goes on. Louisa works at the Eaton’s Centre, Anita at a bookshop across the street, and she gorgeously captures the spirit of the time, of youth and possibility, of life in the city.

When Louisa’s condition worsens, she decides to leave school, and ultimately moves to Vancouver to live with her boyfriend, and Lahey consoles herself that it’s like practice, that she’ll be losing her friend before she actually loses her. Lahey herself on the cusp of her whole life, as her friend is on the verge of losing hers, and she explores this strange conjunction 25 years later, how impossible it was to understand it then or even now.

The connection is different in Marg Heidebrecht’s collection of essays, In the Shade: Friendship, Loss and the Bruce Trail. Heidebrecht and Pam have known each other for years, part of the same community, circles of children. But now the children are grown, and the women are contemplating new horizons. Pam, upon retirement, declares her intention to hike the Bruce Trail, 885 kilometres stretching across southern Ontario, and Heidebrecht decides to join her, the two friends venturing out together and reaching their goal in pieces, over the course of four years. Shortly after their accomplishment, Pam is diagnosed with cancer, and Heidebrecht’s book is a memorial to their friendship, to the power and fortitude of women at midlife, and to the wonders of nature and rewards of walking and hiking. The essays are rich and funny, language sparkling, and the storytelling marvelous, packed with practical advice (stow your water bottles in each other’s backpack side-pockets=GENIUS), amusing anecdotes, and tales of the mistakes and misadventures essential to any journey being memorable.

I loved both these books, which are books about grief, but which are uplifting for the way they capture what is lost, just why the weight of grief is so enormous. Celebrations of women’s friendship, both of them, the kinds of stories that aren’t enough told.

June 16, 2020

Gleanings

- It may be a little faint, but I can still feel the pulse of my city.

- I think if we just each quietly did something positive… this can be something.

- Caitlin Moran has a new book on the way.

- It wasn’t until the late 1920s that technologies in dance photography evolved to allow photographers to capture their subjects in flight.

- I don’t need a pandemic to stay home and notice the minutiae of daily life

- Another recent insight: it’s possible to be grateful and nauseated at the same time.

- These are beautiful times and I am lucky to be alive right now.

- Fact is, I’ve already been down this diversity road to nowhere.

- Who wants to eat a good supper should eat a weed of every kind.

- Even before the doorbell rang, through the side window, I could see someone holding flowers.

- When I was fourteen I got arrested often.

- Whenever I decide to buck a trend and do something my own way, I yell “I’m going rouge!” with gusto.

- Almost every time I go to make something that involves my sewing machine I have to go to the YouTube video about how to thread the bobbin.

- When you’re a writer, most of the time your work is invisible.

Do you like reading good things online and want to make sure you don’t miss a “Gleanings” post? Then sign up to receive “Gleanings” delivered to your inbox each week(ish). And if you’ve read something excellent that you think we ought to check out, share the link in a comment below.

June 11, 2020

The Heart Beats in Secret, by Katie Munnik

There is a convention to covers of books by women, and the cover for Cardiff-based Canadian Katie Munnik’s debut novel The Heart Beats in Secret fits that bill. A woman shot from behind, a dress to suggest the domestic, the house in the distance—and even the title with its secret. A reader might think that they’ve read this book before…but stay with me. What if I told you that Munnik considers among the essential literary companions in her creation of this book not only Ina May Gaskin’s Spiritual Midwifery, but Basho’s haiku? Or that the house in the distance on the cover is haunted by a wild goose?

Not literally haunted, of course, because the goose is living, and Pidge, who has inherited the house on the east coast of Scotland after her grandmother’s death, discovers it in the kitchen. Which makes it difficult for her to perform the task at hand, namely to get the house cleaned out and ready to sell before she heads back to her home in Canada. But then the goose is not the sole distraction—there is a relationship back in Ottawa that Pidge seems ambivalent about, plus the potential for secrets to be discovered amongst her grandmother’s things, for questions to be finally answered.

The narrative moves between Pidge in 2006; her grandmother Jane in 1940 who has just wed a husband who has gone to war, new to a village where she knows no one; and Jane’s daughter, Pidge’s mother, a nurse who immigrates to Montreal during the later 1960s and becomes part of a community supporting midwifery in the Quebec wilderness, arriving at motherhood also along the way. Each of them women venturing into the unknown, connected to each other, but also on her own, a pioneer. Their narratives far from nesting dolls, fitting into one another tidily, but something very different. As Munnik writes in her Launchpad post on 49thShelf, “Because my story plays with the shifting sands of family memory, I discovered I could play with non-chronological detailing, letting the characters and reader learn about events or motivations in different orders…In that way, writing a novel could be like writing a poem.”

This story is slow and quiet, an altogether pleasant read, but this also makes the novel’s interestingness easy to undermine. The strange ways that the three narratives fit together, the inherent mystery in the text, that the answers never turned out to be what I thought they were going to be. For a story so entrenched in the domestic, it’s really not conventional in the slightest. And the storyline of Jane during WW2 was especially resonant to me as I read it during our own anxious times:

“It feels close to the end now, but the end of my tether or the end of the world, I can’t know.”