April 11, 2022

4 Great Essay Collections

Run Towards the Danger, by Sarah Polley

I’ve read a run of great essay collections lately, which kicked off with actor/director Sarah Polley’s bestselling new release. It was a book I regarded curiously, at first, because the premise was strange: six essays about various experiences from Polley’s life, in which an adult perspective circles back on childhood trauma. Polley is a former child actor and now an acclaimed film director and writer, and I wondered if the whole project might be a gimmick, but then I kept hearing from reader after reader about how excellent the book actually is. And they were right. I loved this one, its searing, visceral writing, its willingness to complicate, to circle back and around, its acknowledgement of darkness and light, often in the very same place. Brave, original, and interesting, Polley writes about growing up too soon after the death of her mother, about stage fright, exploitation as a child actor, about carrying the story of her experience abuse by a notorious celebrity, about a complicated pregnancy and introduction to motherhood. Polley has had a remarkable life and she owns both her privilege and her trials at once, demonstrating that our experiences and our perceptions of experiences are multitudinous and ever subject to change.

Spílexm, by Nicola I. Campbell

Celebrated children’s book author Nicola I. Campbell’s Spílexm (which means “remembered stories” in the language spoken by Nlaka’pamux in British Columbia) is a beautiful collection weaving poetry, memoir, journals and letters to tell her story of becoming as Nlaka’pamux, Sylix, and Metis, and the daughter/granddaughter/etc of residential school survivors. This is a story of grief and survival, and a testament to the remarkable powers of love, family ties and personal will to overcome trauma and design a better future for one’s self, and Campbell imagines the same for Indigenous people across Turtle Island. My favourite parts of the story are those where she writes about canoe racing, discovering her own power and the power of community. This is such a generous and achingly beautiful offering to the world.

Send Me Into the Woods Alone, by Erin Pepler

While this collection is subtitled “Essays on Motherhood,” it too is a story of becoming, a story of womanhood and daughterhood, and personhood. Truly it’s a smorgasbord of goodness, essays recounting a difficult pregnancy, the details of labour (that one is called “A Million Hands in One Vagina”), and onward through the years. At the beginning I wondered if these essays might suffer a bit from the desire to be relatable and inclusive at the expense of specificity, but such concerns fell away as Pepler delves into her own story and writes with such candour about her struggles with anxiety, and about how her own family experiences growing up inform her parenting now, for better or for worse. The collection is tremendously moving, but also very funny—I kept reading parts aloud to whoever happened to be in the room with me. Like motherhood itself, Send Me Into The Woods Alone is equal-parts light and dark, joy and misery, another writer who’s unafraid to be complicated and tell the truth.

I Came All This Way to Meet You, by Jami Attenberg

And finally this collection by American novelist Attenberg, the story of her Midwestern roots, her years in New York, and finding home in New Orleans, an unlikely outcome for someone who spent years couch-surfing, which turned into years staying in friends’ spare rooms as their lives stabilized but hers didn’t for such a long time. Coming later to writing, put off by an assault in her first year of undergraduate studies, a story she tells in connection to the testimony of Christine Blasey Ford about how Supreme Court nominee had sexually assaulted her years before. Attenberg writes, “Why do we believe these men are the best when they are the worst? Why do we hold on to them?” In this collection, Attenberg writes her process of coming to own her story and her voice, all of this underlined her her persistence in staying true to her art through the ups and downs of the writing life and her determination to succeed as a writer.

April 8, 2022

Beauty

Poor lighting, really crummy phone camera, flowers just past their prime, and LOOK! The beauty.

April 5, 2022

Gleanings

- In some ways, the book feels more like an allegory for moral imagination, one man’s story that begs every person to ask piercing and hard questions of themselves.

- So the grey squares can be signs of success, too, for what that’s worth.

- That sorrow remains, with all of its complications, but as time passes for us but not for him, it’s hard not to feel that now we are the ones leaving him, which we did not choose to do—which we desperately do not want to do, but can’t help or stop.

- I’ve often marveled at the strange, cyclical nature of life and creativity. How the things that I sketched five years ago, with no real thought, have elements that are now a part of my current art practice in ways I never planned for.

- I never expected eleven to come so fast, and to take so long.

- There’s so much I’ve missed, and miss. I meant to learn more about botany, and maybe it’s not too late.

- How do I start having my own life now, at 47, leaving them to grow and become more independent, without feeling a guilt that is tied to loneliness from a fourteen-year-old girl from 33 years ago?

- For it never becomes common place for me to witness, to experience birth, life, the beginning, divinity, mystery.

- Which then leads me to think more about process and practice. About forming a body of work out of the squelch of our own many clicks. About being more deliberate. But then needing the freedom to just make images….(I go back and forth on this obviously).

- When everything shut down two years ago, I was so burnt out and overstretched that my main feeling was relief at not having to do everything all the time for everyone. In the interim, I’ve recalibrated my boundaries, and I feel more capable of saying yes and no with greater understanding of the costs and benefits of each.

- The light, the dark. Within. Without. There’s never really one, without the other.

- Once again, I’m resolving to take back home with me the sense of freedom I experience while on adventure.

April 4, 2022

Seasons

I am so grateful for seasons, and not just because some seasons mean I finally get to shake off my winter coat. I am grateful for seasons because they remind me that change is healthy and good, that cycles are an important part of being a living thing, and that nothing is ever standing still even when sometimes it appears to be.

I spent the first two months of this year having a restful season, with lots of spaciousness, room to reflect, and reconnect with myself after a difficult time. Believe it or not, all that quiet was fruitful, and all of it helped me feel like myself again, and then suddenly one day at the beginning of March, it occurred to me that what I was missing was writing and it was time to begin a new creative season, which has proven as wondrously restorative as my period of not writing had been.

If you too are feeling like it’s time to start creating, I’m happy to remind you that my online course, FIND YOUR BLOGGING SPARK, is ready whenever you are to help take your ideas in an exciting, inspiring direction. Email me with any questions and learn more on my Blog School website.

March 31, 2022

Loopy

The past two years have, in some many ways, had me feeling as though I were caught in a loop, and such feelings were really what drove me down in December. I remember feeling devastated by posters around my neighbourhood—a local church had organized a Christmas Eve carol sing, and now all the posters had stickers pasted over them that said, “Cancelled Due to Covid.” A friend’s child was playing music in a local show, and that event got shut down. Once again, so many plans were shifted, just when we were beginning to think it was time to venture out into the world again. It felt like a trick.

One of my favourite things about right now, even with case counts rising locally, is how far away most of us are from that moment in which the idea of other people having fun made everybody furious. As Miranda Featherstone writes in today’s New York Times, “I am tired of judging the Covid choices of strangers.” I got tired a long time ago. For the last year, as vaccines arrived, I’ve been overjoyed to see my friends returning to the activities and pursuits that define their lives. Even sports. I hate sports. But I’m overjoyed at the sight of a packed stadium, and not just because I don’t have to be there. It means the world. It means connection. I welcome every little bit of it.

And in some ways, even with the infernal loop of decline and rise of case counts, things are starting to feel a bit less loopy? That friend’s child got to play their show the other week. Plenty of pals went away for March Break for the first time in three years. The cookbook writer Emiko Davies, who I started following on Instagram in March 2020, when Italy (where she lives) went into lockdown, has finally travelled to Australia with her children to see her parents. All these people I don’t even know—Sarah Harmer’s FINALLY getting to go on tour for her album Are You Gone? There is a week in May when I’m going to two evening concerts and a theatre matinee!

I love it. I’m here for it. Get vaccinated and booster, put on your fucking mask, and let’s do it.

On March 16 2020, we were due to fly to Manchester to visit my husband’s parents, and our one-year-old niece. My husband’s father was very ill from cancer, which made this trip especially pressing, and I still remember, the week before our departure, talking with my dermatologist about how it was going to be fine, and it was Italy and Iran that were the hot-spots. I remember how stressed out we’d been the week before that, riding the TTC and anxiously applying hand sanitizer, and how I’d shout at my children not to touch anything. They just couldn’t get sick. Because a pandemic is very a bad time to be flying across the world with a bronchial infection.

But of course, we didn’t go at all. That week following my appointment at the dermatologist (the last crowded waiting room I ever sat in) was one in which we all lived through about a decade of shifts and radical change, it became clear that travelling at this moment would not be responsible, and it would have been halfway through our time in the UK anyway in which the Prime Minister would have implored us all to come home. It would have been stressful beyond belief, and I know that cancelling our trip was the right thing to do that moment.

Two weeks from today, we’re scheduled to try again. And in some ways that is driving me crazy, especially as case counts rise. As though I were the centre of a sci-fi plot and this elusive trip to the UK a destiny in front of which the universe is determined to throw up walls, make impossible. Like Natasha Lyonne in Russian Doll every time she tries not to die. (Cue Harry Nilsson).

Although I even have a rational side that knows it’s probably going to happen. (!!) And knows too how wondrously cathartic it’s going to be when it finally does, to finally break the spell, to close that loop. Fingers crossed.

March 29, 2022

Gleanings

- What’s in a song? What’s in a robin song heard in the trees on a March morning?

- My daughter becoming a mother reminds me of what those first few months of motherhood are like.

- As they say, if you want to get fit, hang around with fit people. And, if you want to read more, hang around with readers!

- Every year around this time I see tulip leaves emerging in the gardens around Victoria College and I worry that they’re too eager, that they won’t survive another Spring snowfall.

- What if, after two years, we actually understood each other better instead of being convinced that only one of us is right.

- I’m not sure why or when I imagined I was supposed to know things or have a “valuable perspective” to offer. Or, you know, some kind of wisdom. Ha.

- I won’t suggest that braiding a rag rug is a quick and easy zero-waste solution to repurposing your used bedsheets. There’s nothing quick about making a rug, and while the actual process is easy enough, it’s a project that demands time and staying power, not to mention some muscles and balm for your soon-to-be tender pinky finger.

- But thick black eyeliner and jelly shoes aside, I’ve always found that the most difficult thing to express when people poke fun at the decade, is how we lived with a thick air of potential nuclear annihilation and destruction that permeated even the most French Formula-hardened ‘do. It was everywhere. And it followed us around for years.

- Our eyesight may be changing, but we start to see wider and further, from a different perspective. Our inner lives are richer than they were before. And we know there’s still more to know.

- And very practically speaking, writing every day has me quiet … listening, noticing, observing, reflecting … a necessity in order to have something to put down on this page each evening, trusting and seeing that when I arrive here, I don’t need to have it all, or any of it figured out, but just allow what already exists …

- Here’s to sitting in the darkness, then, with beauty and love, just sitting on our laps like cats — an orange one and a gray one.

- I’m not going to let my messiness stop me from loving this wild and precious life.

Do you like reading good things online and want to make sure you don’t miss a “Gleanings” post? Then sign up to receive “Gleanings” delivered to your inbox each week(ish). And if you’ve read something excellent that you think we ought to check out, share the link in a comment below.

March 28, 2022

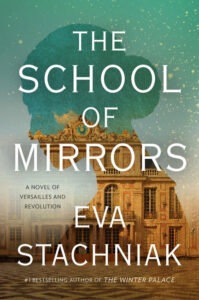

The School of Mirrors, by Eva Stachniak

Last week, I read the same novel all week long, a novel set in 18th century France, no less, neither of which is my usual speed, but my friend Eva Stachniak is such a magnificent author that it was only a pleasure spending time with her latest, The School of Mirrors.

The story begins with Veronique, a young girl taken from her destitute family to be trained as courtesan to a Polish Count. But it turns out that the Count is actually the King of France, the girls discarded when he tires of them, all of this orchestrated by the King’s mistress and a network of other figures at Versailles.

Young Veronique soon becomes pregnant, and is taken away to give birth in secret, her child taken from her, and Marie-Louise overcomes a lonely and difficult childhood to study midwifery and pursue one of the vocations available for women. As with the girls of Deer Park, from whom Veronique’s story is imagined, the story of these midwives is taken from life.

By the dawn of the French Revolution, Marie-Louise is married to a radical lawyer pushing to make France into a Republic, and she keeps quiet about the story of her own origins, which she knows so little of anyway. But as the politics of the moment grow more and more intense, the consequences of Marie-Louise’s ties of Versailles become much more fraught. When she finally reconnects with her mother, who is poor and suffering from dementia after such a difficult life, the list of secrets she’s having to keep is growing ever longer.

“‘The present circumstances’ were growing worse. Hortense would come home from the market furious. There was no spring lettuce. Leeks had vanished. Vendors pushed wiltered carrots on her and when she protested told her not to be too picky if she wished to be served at all. Her regular cheese merchant tried to charge her almost double what he charged last week so she had to go elsewhere. Bread had gone up in price again. People said it was because of vagrants, though what vagrants could have to do with the disappearance of leeks or the price of bread was still a mystery. Try saying that at the market though. You get spat on. Or pushed into the mud. A young fellow got beaten up because a fishmonger called him a king’s spy. No one minded their own business anymore. Everyone had an opinion to defend. The more outrageous the better. People no longer talked, but yelled. Where was it all heading? Where would it end?”

The School of Mirrors

I wondered, upon reflecting on this book, if it’s not a case of “history repeating” as much as “this is how it always is.” The instability, drive for revolution and change, and also appetite for war, and how while women are never the drivers of any of this, they’re the ones left to pick up the pieces, to keep things going, to put food on the table, delivering the babies, delivering the future, birth and death being their business, always.

Stachniak’s writing is wonderful, the characters gorgeously rendered, and the era brought to life in terrific fashion. The School of Mirrors is an excellent read, providing fascinating insight into the experiences of women and their proximity to power, and meaningful connections to right now.

March 25, 2022

Good Bookish Things

One of the highlights of my March has been hosting the virtual lunch for Danielle Daniel’s debut adult novel Daughters of the Deer, which continues to appear on bestseller lists across the country—which is just the best news, and I’m so thrilled for the book’s success. As a token of thanks following the event, Danielle was kind enough to create a beautiful image of a a reader and my book, and I couldn’t love it any better.

March 24, 2022

Thinking About Masks

(Background: Ontario began lifting indoor masking requirements this week, after nearly two years.)

I am very pleased every time I see that a business is continuing to require masks in their establishments, not because I am wedded to masks per se, but instead because I fully respect the rights of other people to feel comfortable in their workplaces and to make such calls that feel right for them, and I’m so happy to accommodate that in my day to day life.

Because masks aren’t hard.

The whole masking issue is made simpler for me anyway, because while I’ll agree that, in general, the risks of Covid are quite low right now (cases tend to be mild), and perhaps it doesn’t make sense for everyone to mask up for an illness that leaves most people feeling crummy for a couple of days, the stakes are different for my family at the moment, three weeks out from plans for a big trip that was already once cancelled due to Covid and we’re just absolutely desperate for it to happen this time.

Basically, we can afford to get sick right now.

Though even if we didn’t have plans to travel, I suspect I’d continue to wear masks in indoor spaces. Because, as I said, masks aren’t hard. Especially since there are vulnerable members of our community who can’t afford to get sick ever. Especially since I don’t think that wearing a mask is more difficult than being sick is. (I had pneumonia in 2015 that left me bedridden for weeks and was the most physically devastating experience I’ve ever had.)

I am looking forward to a spring with travel plans, and tickets to plays and concerts (!!) and to me wearing a mask is just one more way to ensure that any of this is actually going to happen. (OMG PLEASE!)

While I am very pleased every time I see that a business is continuing to require masks in their establishments, however, I know this isn’t going to be universal, and I’m trying to ease myself into the fact that this is okay. I’m trying to ease myself into the fact that we’ll not be wearing masks forever, and I don’t want to be wearing masks forever, and there are plenty of smart and good people I know who are thrilled about the end of mask requirements, and they might have different priorities, understandings, or experiences of all this than I do.

As with everything during the last two years, there is no one right answer to the challenges of the current moment, and I continue to find that interesting.

Though I am sorry about all the bad actors and loudmouths whose efforts have made understanding this particular point of view incredibly difficult, who have turned the lack of a mask into something aggressive and threatening when I know this isn’t necessarily the case. But it’s hard to think otherwise living in a neighbourhood that, for example, has put up with two years of unmasked jerks barging into shops and confronting employees as a political stunt as part of weekly anti-public health rallies. Who have been the ones who turned masks into a symbol, when all along they have been a tool, an incredible tool that’s meant I’ve been able to ride public transit, do my grocery shopping, send my children to school, and so much more.

In a way, I am most grateful for the end of mask requirements, because it’s going to mean the end of somebody not wearing one being perceived as an aggressive act of political defiance. Because I find all that so sad and disappointing, and I’m just tired of that. I continue to be baffled that two years into a public health emergency, there are people who’ve constructed entire identities on the basis of not caring for others. Which is separate from the other people who’ve tied themselves up in knots to convince themselves that rejecting masks and vaccines is actually what caring is, because it’s the masks and vaccines that are the true danger, these people having proven themselves to be particularly susceptible to misinformation. It’s all very exhausting.

(Have you ever smiled at a baby while wearing a mask and the baby has smiled back at you? This has happened to me. I’m no scientist, but I can tell you that masks and vaccines have hindered my children’s health and development not one iota. The overstatement of harms from these tools have made it impossible to have any real conversations about any of this.)

I have worked really hard to not to make my mask part of my identity. I have worked really hard to be flexible, not married to consistency (because Covid certainly isn’t!), and to be open-minded, and not histrionic or hyperbolic in my discussions around any of these issues. I have been bothered that as we move away from public health restrictions, many of the same people who’ve been fervent public health supporters over the last two years are losing faith because new public health guidelines aren’t necessarily those they agree with. I’ve found it interesting over the last few months that there’s been an overlap between anti-vaxxer parents and super Covid-cautious parents—they’re all threatening to take their kids out of the education system, insisting the public health decisions are motivated by nefarious factors, deciding that small risks are worth undermining general public health for.

Something else I find interesting is people insisting that their perspective on all this is stemming from justice, from community care, but the end result of this is that they’re just absolutely furious with a lot of their neighbours, which is kind of ironic.

I have to keep reminding myself not to imagine that I’m morally superior to the people who disagree with me. And not just because it’s morally superior not to think that you’re morally superior, but also because I’m not, and neither are you, and all of us, at our best, are just trying to muddle through, to figure this out together.

March 22, 2022

Gleanings

- If anything, ballet is forcing me to rethink my relationship with my middle-aged body and instead of noticing only the beginnings of older age descending upon me, I now marvel at what my body is capable of and the incremental changes I’ve seen as I’ve learned to stand with more confidence and courage. And as for the imperfections? They’re part of being alive.

- …still one of the finest books of short fiction to appear so far in the 21st century.

- The key for me is that I keep writing, even if what I have to say is as frothy as a cappuccino. Because when the urge does come for me to express something weightier, I’m more likely to have the words.

- I missed the practice of framing the world through my viewfinder. I began wondering what I would find if I photographed my city as I would photograph Rome? If I looked at Edmonton, so often described in terms of ugliness, with love-coloured glasses?

- “In terms of the scope of the war, it’s the Russians who have done badly,” he says. “The ground campaign has been pathetic. And the whole world is watching.”

- The thing about having a practice, is to remember that it’s just that, a practice. It’s not something ever present, but something to continue to work toward. Sometimes there’s joy, sometimes not.

- The greatest gift I can imagine is if you give yourself the gift of a book.

- The rest of the intentions were along the lines of: “Make more time for myself”; “Learn to accept myself more”; “Learn to say no more often.” I wanted to feel empathetic towards the women, but all I could think was: blah…blah…blah…Self-improvement 101 stuff. (Perhaps I needed the retreat more than I thought I did?)

- Recently, I shared a photo of myself on an island beach trail. I looked at the photo and thought this is who I am.

- Somehow, that is, the end of Owen’s life has to become part of the story of my own life: rather than considering it a break, a catastrophic rupture, in that story (the way it feels to me now), I need to learn to see it as belonging to a new, different continuity. (Mrs. Ramsay, though dead, is still very present in “The Lighthouse.”)

- So I decided to keep writing, to let the plot unfold like the textiles in the small museum run by the cousin in Lviv, a city as haunted as any, and even if I can’t return, my character can go for the first time. She can hear an opera, drink coffee on Serbska Street, look at old books at the market by the Fedorov monument, and sit with her cousin, drawing the tree that gathers them both into its root system, families on each spreading branch.

- I began writing poetry and doing contemporary dance around the same time in high school, and they’re definitely connected for me—they’re both non-linear, non-narrative, and imagistic

- How we think we are one independent organism, living, breathing, acting on our own, and how I have so often felt so assured that I could, or even should do it on my own… and yet, there’s no possible way that we can’t not be interdependent. We need and are dependent on one another, and each provide gifts, seen and unseen, spoken and unspoken for the other, and receive what we need and more from others in return.

Do you like reading good things online and want to make sure you don’t miss a “Gleanings” post? Then sign up to receive “Gleanings” delivered to your inbox each week(ish). And if you’ve read something excellent that you think we ought to check out, share the link in a comment below.