October 31, 2021

Hauntings: Books That Won’t Leave Me Alone

I loved this book, which I thought was going to be a smart and funny novel about modern dating and the phenomenon of “ghosting,” which it was, but it was also so much richer and more meaningful than that as Alderton’s protagonist comes to understand the different kinds of ghosts that are haunting her experience—ghosts of a past romance, of her childhood, and also of her relationship with her parents, which is changing and becoming more complicated as her father’s dementia progresses.

*

Reading the latest Laura Lippman is a summer holiday tradition for me and my husband. We love her, and her latest, a literary homage to Stephen King’s Misery, is a marvelous mindfuck. Lippman moves from crime fiction to psychogical thriller in this novel about an author who becomes confined to his bed and then proceeds to be haunted/hunted by a character from one of his novels. We loved it, and the meta elements of it all were delicious.

*

The Other Black Girl, by Zakiya Dalila Harris

This one checked a lot of boxes for me—set in the publishing industry, biting social commentary, and twisty and weirder than you’d think, billed as “Get Out meets The Stepford Wives.” Naturally, Nella is pleased when the new hire at her office means she’ll no longer be the only Black girl at her publishing company, but her comradeship with Hazel turns out to have an edge. The novel is a statement on racism and feminism, the notion of how much progress is enough, and a culture of scarcity that means supporting others could mean hindering one’s own chances of success. But it’s also more than that, totally bonkers, involving an underground movement, and a fight back after decades of oppression.

*

Malibu Rising, by Taylor Jenkins Reid

Everyone keeps telling met that the The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo is her best, but I haven’t read it yet. I did read Daisy Jones and the Six and liked it well enough, but I LOVED Malibu Rising, a holiday dream of a novel that I read in a single day and then forced until my husband who liked it as well as I did. Complicated family dynamics, Americana, California, and the sea. The novel had some furious momentum and I found it unputdownable. I can’t think of any literary ghosts in this one, but characters are indeed haunted—by lost loves, and the people they used to be.

*

A Thousand Ships, by Natalie Haynes

We read The Odyssey earlier this year, and I ordered this book afterwards, inspired by that book and also events in The Iliad, though I confess that I wasn’t chomping at the bit to read it, figuring it would be difficult. Those Greeks, you know? But I loved it. Read it right after Malibu Rising and just as quickly while we were on holiday this August, and then my husband read it, and then our daughter did, and it brought these characters to life in the most vivid, devastating way, because this is a novel about death and loss and destruction after all. There is nothing heroic in these wars, which tell the story of how their experienced by many different women. I can’t wait to read The Iliad now

October 26, 2021

Gleanings

- But you know, the beautiful thing about a blog is that I’m not forcing anybody to read these posts, should I choose to write every day- and every so often, something I write that makes me feel good might just make someone else feel good.

- I believe that, to truly experience the world, you need to be out in it.

- Was there a Wanda? Maybe. Doesn’t matter. This is fiction. In fiction everything and nothing is possible and everything and nothing is real.

- The next day the trees had disappeared. Were they stolen in the night? Had the city reconsidered planting trees? Did whoever delivered the trees put them on the wrong street? In Montreal there are always many possibilities. The workings of the city and its employees are not transparent.

- I’m so grateful for friends like this, the shared meals, the stories, the laughter, the complete letting down of hair and being ourselves.

- But in the room yesterday, surrounded by photographs of Barbara, hearing from friends and family who knew her as a girl, then a young bride, a young mother, I thought that our lives are somehow liminal. Between.

- It’s here that I am full of hope and possibility. The kiln hasn’t had its wicked way yet. No cracking, blistering or warping. I can see the finished piece exactly as I want it to look. I

- What fascinates me most is family narratives and the intergenerational impact on women. Are we more resilient when we know our stories? Do we learn to break the cycle of generational patterns? Do our generational stories create bridges or chasms? Those are only some of the questions I want to explore.

- Oh, didn’t that quotation find me at just the perfect moment? I responded on Twitter that the “distanced intimacy” of reading takes many forms.

- After all, Amelia Earhart, with whom Grace becomes obsessed, is not a straightforward symbol of escape or liberation: sure, she broke barriers and flew away, but eventually she also, tragically and mysteriously, never came back.

- Together we were living out the narrative of this time together as it unfolded, it just too bad there weren’t any guitars or fiddles.

- It may not be quite the same as sitting at a table on a sidewalk in Europe, but a little bit of butter, a little flaky morsel, goes a long way.

- We need to make a point to fill ourselves up. I need to, as JGO says below, let the bitterness sink to the bottom of my life. Allow myself to take the joy to go. And this is found, often, in the company of good people, good friends, and yes, often in the company of women.

Do you like reading good things online and want to make sure you don’t miss a “Gleanings” post? Then sign up to receive “Gleanings” delivered to your inbox each week(ish). And if you’ve read something excellent that you think we ought to check out, share the link in a comment below.

October 25, 2021

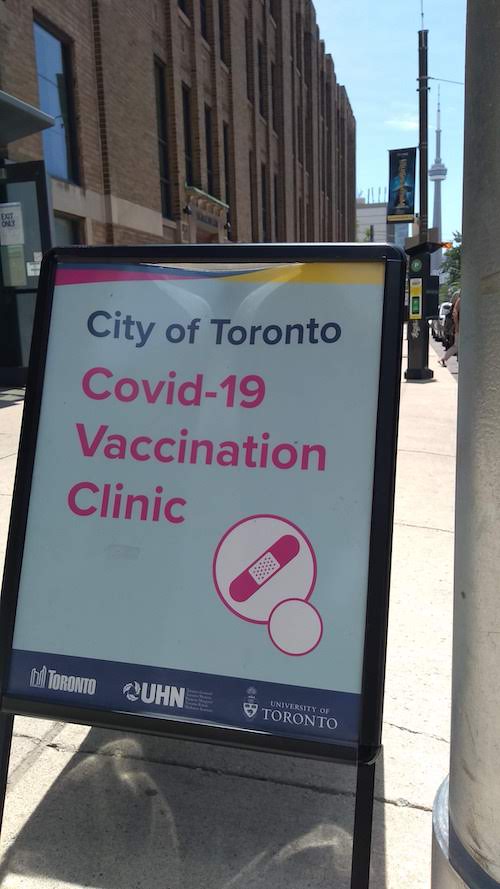

About Last Spring: The Vaccine Narrative I’m Holding On To

I’ve almost forgotten about last spring. Have you?

Because it’s been about 300 years since then, I think. We had a federal election, and a summer of climate emergencies, and the anxiety of school reopening, and real life returning, albeit slowly and cautiously here in Ontario, which seems to be paying off with a flattened curve, thank goodness. KNOCK ON WOOD.

But all this has been much overshadowed by the noise of a very small minority of our community members who distrust and refuse vaccines, community members whose grasp of science is perhaps as slight as their grasp of public relations—because I could have told them that the tactic of blocking hospital entrances and yelling at sick people receiving life-saving treatment was probably never going to win much support. A small minority of our community members who seem empowered by the idea that they’re part of a much larger movement, an illusion that fizzles out when you check out statistics such as that 73.7% of Canadians are fully vaccinated or that 87.9% of all eligible Ontarians have received at least once dose. Also 77.96% of Canadian 12-17-year-olds are fully or partially vaccinated, which seems to bode well for uptake once vaccines for 5-11-year-olds become available (and BRING IT ON!).

It’s such a far cry from the “vaccine-hesitancy” message that the media insisted on perpetuating as soon as vaccines were available, even as people were lining up around the block in the rain at 4 o’clock in the morning to get them. And it’s a far cry too from the anti-vax messaging we’ve been hearing from last hold-outs over the last two months, people who are becoming more and more desperate to own the narrative as it slips further and out of their grasp, and it becomes clearer that almost everyone you know believes in the Covid-19 vaccine project.

Back in April, however, there was no doubt about this. Just six months ago, at the peak of a devastating fourth wave that saw patients in field hospitals and pregnant women in ICUs, the Astrazenaca Vaccine was approved for people over 40, and suddenly we had a surge in vaccinations here in Ontario that brought us into a new era of immunity, one whose payoffs we’re all benefiting from right now, whether we’re vaccinated or not.

None of this was inevitable—we came into this new year hoping to get our first doses by September, if that. Opposition parties spent the first few months of 2021 bitching about the government’s “botched vaccination rollout,” never mind that we were lucky that vaccines existed at all. I remember the first person I knew in Canada who got a shot, a friend who’s a first responder, and we made him a celebratory card. In England, my mother-in-law got her shot. Other friends who worked in healthcare were vaccinated. And then there began to be more of it—friends who are Indigenous, those with underlying conditions. Every single one of these shots such a victory for every single one of us, bringing us one step closer to the project of herd immunity. There was a whole lot of crying for joy. And then in April, my parents had their shots. My mom got hers on Easter Sunday when we were in town for an outdoor visit, masks on. What a miracle, it seemed like. It was really happening. We just had to hold on, keep going.

I remember a few weeks later, it was Sunday night. Just hours after I’d read news headlines about AZ being approved for those over 40, I got a text from my friend M alerting me to appointments available at our local Shoppers Drug Mart the following week. I received that text while having a bath, and leapt right out again, dripping wet, wrapped in a towel, and phoned Shopper’s Drug Mart, which closed at 10:00. It was 9:30. I had to call back a couple of times before I got through, but when I did, I snagged an appointment for Stuart and I for the following Wednesday. And then I texted the news to my friend K, and my friend R, and both of them would get appointments for that very same week. I helped another pal get an appointment out of town. Other friends would also find appointments through similar ways, and still others could not get appointments at all and were angry and frustrated that they seemed so hard to come by. Huge teams of volunteers (Vaccine Hunters!) began helping to track down vaccine appointments online for complete strangers. On my neighbourhood Facebook group, people were sharing news of availability. More and more appointments were being rolled out all the time, and people were stepping up, helping others step up, and it was one of the most terrific examples of COMMUNITY that I’ve ever been witness to, let alone been apart of.

Not to mention the amazing public health agencies who made the whole thing happen. Sometimes even though it seemed like a systematic disaster—the lack of a central booking portal, random allocations of doses, the significant problem of vaccine availability not being accessible where infection rates were highest. Oh, it was a mess, such a mess, but it was also such a massive endeavour, and by the time I was booking my second appointment and even an appointment for my 12-year-old (CAN YOU BELIEVE IT?) things were smoother, and eventually there stopped being so much to complain about, and by the onset of summer, nearly everyone I know was fully vaccinated.

And this is the vaccine narrative that I’m going to be holding on to. What a rush and what an honour it was to be part of this singular moment, a moment that helped us turn a corner onto much better days and whatever comes after this. (We understand too that Covid-19 vaccines need to be made accessible to people all over the world—and to that end, UNICEF Canada recently raised $9.5 million for their #GiveaVax campaign, to be matched by the government of Canada.)

I’m so grateful to the millions and millions of people who got us here, and the way that each and every one them underlined my faith in people and my neighbours and US.

October 21, 2021

Back Home Again

After months of floundering around (and not so fruitfully) in the Land of First Drafts, it’s such an absolute pleasure to find myself back at work on a manuscript that has a four walls and a roof, plus windows and doors (not to mention precious editorial feedback). The imagery of a house particularly fitting between this is so much a book about homes and spaces, more rooted in place than anything else I’ve published. And while the story is fiction, many of the places where they’re set are not, homes and apartments I’ve lived in, plus the Lillian H. Smith Library’s Osborne Collection and and the Royal Ontario Museum, and the effect of becoming immersed in this project again is so completely transporting, plus kind of cozy as the autumn weather makes way for the inevitable chill.

October 21, 2021

10 Questions

The excellent Kate Jenks Landry did a Q&A with me on her inspiring blog, and you can read it right here!

October 20, 2021

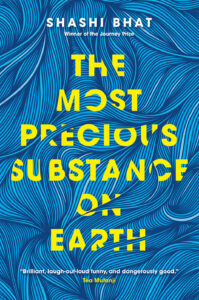

The Most Precious Substance on Earth, by Shashi Bhat

In 2018, when I had the great honour (and pleasure!) of being one of three jurors for the Journey Prize, one of the standout parts of that experience was encountering Shashi Bhat’s writing for the very first time. Although I didn’t know the writing belonged to Bhat herself—the stories were submitted anonymously. All I knew was that “Mute,” which would go on to win the prize, was utterly distinct in terms of its narrative voice, and its clarity, and its point of view. So smart, and wise, and funny, and sad, and I don’t know that I’d ever read anything else quite like it.

And now with The Most Precious Substance on Earth, Bhat’s debut, there’s an entire book of this, and I just loved it, and was just as struck by Bhat’s storytelling as I was the first time I encountered it—her award-winning story “Mute” is actually included in the novel. Which indeed does function as a novel—just as it also stands up an impressive collection of short fiction, as Steven W. Beattie argues compellingly in a recent review—because the entire book is so satisfying and rewarding as a whole.

At first, the appeal was nostalgic, familiar, and I texted my best friends to instruct them to get their hands on this book immediately, because Bhat’s tales of late 1990s high school were just so absolutely transporting to this particular reader (me!) who spent Grades 9 and 10 eating lunch on the dusty wooden floors in the alcove outside the science office of a high school at no longer exists. But it wasn’t only the nostalgia—the stories were so evocative because of the specificity of Shashi Bhat’s eye, which is to the eye/I of her protagonist/narrator Nina, who must seem detached from the outside, and we can understand that she sees everything, even the details she’s still too young and naive to process, such as her inappropriate relationship with English teacher.

It’s all so funny, deadpan, tortured and awful, Nina’s best friend Amy, and her boyfriend, and the way she peels the floors. The absurdity of ordinary experience, which is especially the case in high school, and the novel takes us from Grade 9 to a fateful band trip, and Nina’s coming of age, and the way in which she seems to weigh everything evenly, no judgment. The weight of what her did to her, or what happened to Amy, or what it’s meant to to so often be the only person of colour in spaces that were overwhelmingly white—none of this becomes apparent until much later, and it might be easy for a reader to suppose these experiences don’t actually matter much at all.

But all this is also not to say that Nina is a nonentity, just a simple observer—it’s the specificity of these characters and their experiences that so exalts Bhat’s writing. The baked ziti, and the tomato plants, and that Nina joins Toastmasters, and her parents’ eccentricities—there is nothing general about it, and these are the details that bring these stories to life. They’re also often very funny, Bhat’s prose just as assured and confident. She’s an extraordinary writer, and this is an extraordinarily good book.

October 19, 2021

Gleanings

- My family journey is an affirmation of the beauty and worthiness in life and relationships which are salvaged and repurposed.

- When I pointed out that a recipe book on her kitchen counter was mine, she said, Oh, we’re having sex, I hope you don’t mind. I didn’t mind about the sex. I did mind about my recipe books and cake tins.

- We can all connect to scenes of swimming in the local pool, waiting for the bus or sharing a meal with friends. No doubt, Monet, Morisot et. al. would be fans.

- Does an axis wish for a particular season?

- I’ve been thinking a lot about the words we use to describe ourselves as I step into retirement and cope with the death of my mother.

- I became very adept and meeting people and communicating online, and now this has become the primary way I engage the world.

- So it’s a good time of year to be looking in puddles–what’s real, what’s reflection, where’s your focus?

- I Will Follow Claire-Louise Bennett Anywhere

- Horror means something to me. It gets me through shit. Horror movies have literally saved my life. Maybe not life, exactly, but more like, just … saved me.

- I’m caught up in the details of organizing this ritual. Somehow, I have to free my thoughts of the minutia and write a eulogy. Sometimes there is a tendency to focus only on glorious achievements, while ignoring more down-to-earth, even negative aspects. I want to write about all of it, but from a place of love and understanding.

- My eight year old is obsessed. Can’t stop trying to spend her money on little bits of plastic that squish, or pop or spin. It is making me nuts, causing my inner panic buttons to be pressed about waste and the future and poverty and sea turtles.

- Our long walks up the mountain aren’t quite what they were. Rough ground presents difficulties so we try to find places to walk where the terrain is even. But I have to say that otherwise, things go on as they always did.

Do you like reading good things online and want to make sure you don’t miss a “Gleanings” post? Then sign up to receive “Gleanings” delivered to your inbox each week(ish). And if you’ve read something excellent that you think we ought to check out, share the link in a comment below.

October 18, 2021

When I’m shining everybody gonna shine

I don’t know if I smiled any wider last week than I did at the news that my friends’ new novel (The Holiday Swap, by Maggie Knox!) had made the Toronto Star bestseller list, and with this news came such overwhelming gratitude that other people’s good fortune could be fuel for my fire. And I’m writing this not to be smug, but just because I’m glad, and I’m still not 100% sure how I got to this place (though I wrote about it in a post a few years ago called “How to Get Over Literary Envy”).

I remember many years ago feeling so much more desperate, perceiving other people’s wins as a kind of violation, and no doubt some of the change has come about as I’ve grown older and settled into myself, achieving creative goals that I’m proud of (though I have yet to land on a bestseller list). This process too has taught me how much of success is usually a combination of painstaking work and glorious fluke anyway, which makes it harder to resent it when it lands on somebody else’s doorstep.

Though I will confess that there still exist more than a few people whose success makes me roll my eyes and grit my teeth—but these are mostly petty grievances, and the people in question are largely unknown to me (which, obviously, doesn’t mean that I’m barred from finding them annoying).

The people who matter to me though: I want them to win, and not just because of how I seem to win when they do—but yeah, that part also feels pretty good too.

October 15, 2021

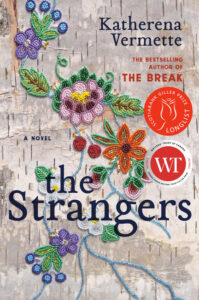

The Strangers, by Katherena Vermette

How does one follow a book like Katherena Vermette’sThe Break, a fast-paced novel with a thriller’s edge that managed to wed deft plotting to high literature, a book that was so rich and satisfying, and brutal and heartbreaking at once?

Five years on, Vermette answers the question with her second novel, The Strangers (though she’s been keeping busy in the meantime releasing poetry and a graphic novel series, among other creative projects), which is billed as a “companion novel” to The Break, and has already been longlisted for the Scotiabank Giller Prize and nominated for the 2021 Atwood Gibson Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize.

The Strangers is not The Break, and though it features some of the same characters, someone looking for a similar reading experience might end up disappointed. Rohan Maitzen’s excellent review notes that the novel lacks its predecessor’s urgency: “Even as time passes in it, The Strangers doesn’t seem to be going anywhere. It ends on a faintly hopeful note, but the conclusion doesn’t feel like a resolution: it’s just the next thing that happens.”

And yet I still found the novel compelling, in the stories of Phoenix, who gives birth in detention and has to give up her baby, and Elsie, her mother, stuggling to stay sober, both of them entrenched on a system that separates women from their children, exacerbating the estrangement and broken ties that created so many of these Indigenous characters’ struggles in the first place.

On a language level, I think the book is really interesting, Elsie and Phoenix’s sections written in the the way that these characters speak, not just in dialogue, the prose not adhering to the usual rules of grammar, though in a natural, easy way that doesn’t interrupt the reading. The sections in the voices of Elsie’s mother, Margaret, and Elsie’s other daughter, Cedar, are very different, reflective of these characters different levels of education, the different company they’ve kept, underlining one of the book’s most salient points: the two people can come from the very same place and each turn out so differently. That what’s easy for one person might prove impossible for someone else.

So no, the plot doesn’t zip, but perhaps the ploddingness is not an accident, especially when you consider time from the perspective of a character counting the days since the last time she got high, or from that of a woman who’s counting down the days until she gets out of jail, trying (and failing) to overcome her violent impulses. Life itself is hardly deftly plotted, which might be the point of the entire book. Instead, it can be random, often lonely, and tragically unjust, especially for those who are marginalized.