May 9, 2013

The Woman Upstairs by Claire Messud

Claire Messud’s latest novel The Women Upstairs is a book that rubs shoulders with so many others, in fact a veritable library which runs the gamut from Dostoevsky’s Notes from the Underground to Zoe Heller’s 2003 novel Notes on a Scandal. Although the latter novel is not referenced in Messud’s book, but rather by critics who haven’t read The Woman Upstairs yet and see implicit connections between these two novels about spinster schoolteachers with transgressing extracurricular connections, and who seemingly destroy their lonely lives with a subsuming obsession with another woman and her family. In Messud’s book, what is the scandal though? To which I answer that there isn’t one. Messud’s is a dark psychological fiction in which plot is not the point and not much really happens, but I dare you not to be captivated by her narrator’s voice, by this novel which begins in a fury: “How angry am I? You don’t want to know. Nobody wants to know about that.”

Claire Messud’s latest novel The Women Upstairs is a book that rubs shoulders with so many others, in fact a veritable library which runs the gamut from Dostoevsky’s Notes from the Underground to Zoe Heller’s 2003 novel Notes on a Scandal. Although the latter novel is not referenced in Messud’s book, but rather by critics who haven’t read The Woman Upstairs yet and see implicit connections between these two novels about spinster schoolteachers with transgressing extracurricular connections, and who seemingly destroy their lonely lives with a subsuming obsession with another woman and her family. In Messud’s book, what is the scandal though? To which I answer that there isn’t one. Messud’s is a dark psychological fiction in which plot is not the point and not much really happens, but I dare you not to be captivated by her narrator’s voice, by this novel which begins in a fury: “How angry am I? You don’t want to know. Nobody wants to know about that.”

The voice belongs to Nora Eldridge, age 37, not incidentally the very same age as Marianne Faithfull’s Lucy Jordan when she realized she’d never ride through Paris in a sports car. And we are not to know until the novel’s conclusion just why she is so angry, assuming it’s mainly due to her dissatisfaction with her place in the world, her own invisibility the result of a life spent pleasing others. She doesn’t get to be “an Underground Woman” or even one of the mad-women in the attic (“they get lots of play, one way or another”), but instead she is “the woman upstairs”, “the quiet woman at the end of the third-floor hallway, whose trash is always tidy, who smiles brightly in the stairwell with a cheerful greeting, and who, from behind closed doors, never makes a sound.”

“Nobody would know me from my own description of myself,” Nora tells us, though it soon becomes clear that her own description of herself is the product of her imaginings, that she has little insight as to how she’s seen by the world, or perhaps she’s making a case for herself in this novel, that she’s taking full advantage of this opportunity to finally make a sound. When a new student arrives in her class, she’s immediately besotted with him, and swept up in the exotic world of his parents, his mother Sirena an Italian artist and his father a Lebanese professor. She admits that she finds their foreignness intriguing, though the reader wonders if its real appeal is that the couple is unable to place her as the outcast she is, and if in their role as outsiders, she’d projecting her own self upon them. And indeed it’s true that Nora does a lot of self-projecting. Metaphors of fun-houses and trick mirrors run throughout the novel, things not being what they seem (Sirena is busy at work creating an installation of Lewis Carroll’s Wonderland), but nothing is more tricky than Nora’s own narration, her fantastically unreliable point of view.

Messud’s novel is also structured as a fun-house, trap-doors and booby-traps springing up if the reader makes the mistake of taking Nora at her word. Which is a difficult mistake to avoid–Nora’s voice is so forceful, persuasive, she perpetually speaks in generalizations and second-person address designed to make us feel comfortable, familiar. “Don’t all women feel the same?” she asks, and you’d be hard-pressed not to respond with a nod, but then, no! There is no such thing as “all women” anyway, and besides, Nora Eldridge is clearly unhinged. On top of being an unreliable trickster of a narrator, she is also blatantly wrong, about so many things, but most notably in her insistence on regarding the world within the limits of gendered binary terms. In this way, the novel recalls Carol Shields’ Unless, another book in which an enraged female narrator stamps her ladylike foot at the systematic repression of womankind, institutionalized sexism which completely exists, but her singular focus upon this obscures a far more complicated reality. Which is not to say that Nora Eldrige’s or Reta Winter’s rage is misplaced, that either should cease their foot-stamping, but just that there is ever and will be ever more to the story.

Nora is threatened by her growing relationship with Sirena, her student’s mother whose thriving career as an artist challenges Nora’s own ideas about the limits placed on women by society. Nora is disappointed by the failure of her own artistic dreams, and Sirena‘s success suggests that this failure could fall more on the individual than on the society around her. But at the same time, Nora is also inspired and empowered by her connection to Sirena, by Sirena‘s attention to her. In their relationship, Nora finds herself as close as she’s ever been to the type of person she’s longed to be and the type of life she’s dreamed of living. Their connection is complicated, power ever-shifting between them, and it’s never entirely clear just who is being played.

The Woman Upstairs also reminded me of Lynn Coady’s The Antagonist, another novel whose foundation is a most remarkable voice, another novel that was sparked by rage and thirst for revenge. In terms of subject matter although not as complex as a fiction, it also had me thinking of The Interestings, which I read recently, another book about friendship, about what happens when different types of people dare to mingle. And even The Great Gatsby–these books in which ordinary people glimpse another, better world and have the nerve to imagine themselves a part of that scene.

But what happens when the scene shatters, when it reveals itself to be a mirror and the character suddenly realizes that she was outside all along? Claire Messud’s Nora’s suggestion is to pick up the pieces and sharpen the shards, though whether she actually will or if this will be just another example of her fruitless longing is just a whole other layer of complexity underlying this formidable book.

May 7, 2013

City Books for Spring

(This post is cross-posted over at Bunch)

Right now as spring arrives and family life moves back out of doors, it is a perfect time to share some books that connect readers to the local and which affirm the goodness of life in the city.

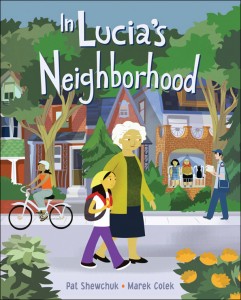

In Lucia’s Neighbourhood by Pat Shewchuk and Marek Cole: This picture book based on the NFB film Montrose Avenue tells the story of “the ballet of the good city sidewalk” (as quoted by Jane Jacobs) in Toronto’s Little Portugal neighbourhood. The book opens with the epigraph by Jacobs, and then goes to render the urban visionary’s ideas in a way that a child can easily understand. A fabulous celebration of city life, In Lucia’s Neighbourhood is most remarkable for its illustrations which are so utterly Toronto: streetcars, three-panelled windows and wrought-iron porches. How wonderful to encounter one’s own world within the pages of a book.

In Lucia’s Neighbourhood by Pat Shewchuk and Marek Cole: This picture book based on the NFB film Montrose Avenue tells the story of “the ballet of the good city sidewalk” (as quoted by Jane Jacobs) in Toronto’s Little Portugal neighbourhood. The book opens with the epigraph by Jacobs, and then goes to render the urban visionary’s ideas in a way that a child can easily understand. A fabulous celebration of city life, In Lucia’s Neighbourhood is most remarkable for its illustrations which are so utterly Toronto: streetcars, three-panelled windows and wrought-iron porches. How wonderful to encounter one’s own world within the pages of a book.

Maybelle the Cable Car by Virginia Lee Burton: This one’s not a Toronto book, but in some ways it may as well be. San Francisco’s iconic cable cars are under threat, as Big Bill the Bus explains to Maybelle: “I just heard the City Fathers say/ the cable cars must go…/ that you’re too old and out of date/ much too slow and can’t be safe/ and worst of all YOU DON’T MAKE MONEY./ What they want is Speed and Progress/ and E-CON-OMY…” San Franciscans don’t respond well to the potential loss of their cable cars, forming a citizen’s committee to save them. Petitions lead to a referendum, and the cable cars are preserved. “We, the people, are the City. Why can’t we decide?” And with that, your child’s political foundation is laid.

Maybelle the Cable Car by Virginia Lee Burton: This one’s not a Toronto book, but in some ways it may as well be. San Francisco’s iconic cable cars are under threat, as Big Bill the Bus explains to Maybelle: “I just heard the City Fathers say/ the cable cars must go…/ that you’re too old and out of date/ much too slow and can’t be safe/ and worst of all YOU DON’T MAKE MONEY./ What they want is Speed and Progress/ and E-CON-OMY…” San Franciscans don’t respond well to the potential loss of their cable cars, forming a citizen’s committee to save them. Petitions lead to a referendum, and the cable cars are preserved. “We, the people, are the City. Why can’t we decide?” And with that, your child’s political foundation is laid.

Jonathan Cleaned Up and Then He Heard a Sound by Robert Munsch and Michael Martchenko: Another book that seems eerily prescient of the current state of Toronto politics. “Subways, subways, subways!” indeed, and somehow a station has appeared in Jonathan’s house. “If the subway stops here, then it’s a subway station,” Jonathan is told by a TTC conductor who has a relaxed emphasis on customer service and instructs Jonathan to go to City Hall if he doesn’t like it. When Jonathan gets there, the Mayor has run out for lunch. Wandering the empty corridors of City Hall, he comes across an old man crying behind “an enormous computer machine.” Turns out the computer is broken and the poor man behind it is responsible for running the entire city. Jonathan gets him to move the subway station in exchange for four cases of blackberry jam, demonstrating that sometimes civic engagement (and bartering) is the only way to get things done.

Jonathan Cleaned Up and Then He Heard a Sound by Robert Munsch and Michael Martchenko: Another book that seems eerily prescient of the current state of Toronto politics. “Subways, subways, subways!” indeed, and somehow a station has appeared in Jonathan’s house. “If the subway stops here, then it’s a subway station,” Jonathan is told by a TTC conductor who has a relaxed emphasis on customer service and instructs Jonathan to go to City Hall if he doesn’t like it. When Jonathan gets there, the Mayor has run out for lunch. Wandering the empty corridors of City Hall, he comes across an old man crying behind “an enormous computer machine.” Turns out the computer is broken and the poor man behind it is responsible for running the entire city. Jonathan gets him to move the subway station in exchange for four cases of blackberry jam, demonstrating that sometimes civic engagement (and bartering) is the only way to get things done.

Jelly Belly by Dennis Lee: This one is not the most obvious contender for the list, but I happened to be reading it soon after reading Edward Keenan’s Some Great Idea, and noticed some parallels between the two books, absurdest story-telling aside. Lee gives us poems not only poems about garbage men and traffic jams, but also a reference to David Crombie in “The Tiny Perfect Mayor” and another poem called “William Lyon Mackenzie.”

Jelly Belly by Dennis Lee: This one is not the most obvious contender for the list, but I happened to be reading it soon after reading Edward Keenan’s Some Great Idea, and noticed some parallels between the two books, absurdest story-telling aside. Lee gives us poems not only poems about garbage men and traffic jams, but also a reference to David Crombie in “The Tiny Perfect Mayor” and another poem called “William Lyon Mackenzie.”

A Big City Alphabet by Allan Moak: I loved this book as a child, and now I love that my daughter is growing up in the very places Moak’s paintings illustrate. City kids will recognize their favourite parks, Kensington Market, the AGO, laneways, variety stores, and other familiar spots. (Hint: A gorgeous print of “I is for Island Ferry” is for sale for $5 at St. Lawrence Market’s Market Gallery, along with other prints from the city’s art collection).

A Big City Alphabet by Allan Moak: I loved this book as a child, and now I love that my daughter is growing up in the very places Moak’s paintings illustrate. City kids will recognize their favourite parks, Kensington Market, the AGO, laneways, variety stores, and other familiar spots. (Hint: A gorgeous print of “I is for Island Ferry” is for sale for $5 at St. Lawrence Market’s Market Gallery, along with other prints from the city’s art collection).

Who Goes to the Park by Warabe Aska: We picked up this book as a library discard, a most excellent find, as used copies are hard to come by. Fortunately, a few copies are still circulating in the library system. In his beautiful paintings which manage to perfectly meld realism and the ethereal (as all the best parks do, really), Aska tells the story of Toronto’s High Park throughout the four seasons, and of all the people and other creatures which are part of life there. (Image courtesy of the Osborne Collection’s online art exhibit).

Who Goes to the Park by Warabe Aska: We picked up this book as a library discard, a most excellent find, as used copies are hard to come by. Fortunately, a few copies are still circulating in the library system. In his beautiful paintings which manage to perfectly meld realism and the ethereal (as all the best parks do, really), Aska tells the story of Toronto’s High Park throughout the four seasons, and of all the people and other creatures which are part of life there. (Image courtesy of the Osborne Collection’s online art exhibit).

How to Build Your Own Country by Valerie Wyatt and Fred Rix: Older kids with an interest in politics and civic life will appreciate this multi-award-winning book from the Citizen Kid Series. It’s a step-by-step guide to building a nation from scratch, and also serves as a fantastic illustration of how our society and those of other countries are structured–however precariously.

How to Build Your Own Country by Valerie Wyatt and Fred Rix: Older kids with an interest in politics and civic life will appreciate this multi-award-winning book from the Citizen Kid Series. It’s a step-by-step guide to building a nation from scratch, and also serves as a fantastic illustration of how our society and those of other countries are structured–however precariously.

Watch This Space by Hadley Dyer and Marc Ngui: Another non-fiction book for older readers, this one about “designing, defending and sharing public spaces.” This one is a nice extension of In Lucia’s Neighbourhood, with references to Montrose Avenue and Jane Jacobs, even, but also takes on a global perspective and discusses how public space is used differently around the world. It”s a vibrant and engaging book with all kinds of suggestions about how to employ its many lessons out on the street.

Watch This Space by Hadley Dyer and Marc Ngui: Another non-fiction book for older readers, this one about “designing, defending and sharing public spaces.” This one is a nice extension of In Lucia’s Neighbourhood, with references to Montrose Avenue and Jane Jacobs, even, but also takes on a global perspective and discusses how public space is used differently around the world. It”s a vibrant and engaging book with all kinds of suggestions about how to employ its many lessons out on the street.

May 6, 2013

Yard Sale Finds

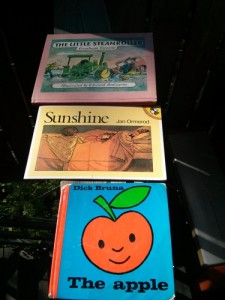

Yard sale season has begun in downtown Toronto! On Saturday, we picked up these three fine volumes, along with Michele Landsberg’s Guide to Children’s Books and Human Voices by Penelope Fitzgerald, for a remarkable $1.25. The Apple by Dick Bruna is as strange and visually appealing as anything Dick Bruna ever published; we love Sunshine by Jan Ormerod, which we’ve had out of the library a number of times (and I am particularly fond of the mother who sleeps/reads in bed until the last possible second, and then runs around the house getting ready in a frenzy. I feel as though I know her very well…); and The Little Steamroller by (the!) Graham Greene is amazing! A picture book this might be, but it’s absolutely Graham Greene, complete with a criminal gang smuggling gold from Africa and terrible English weather. Totally weird, but Harriet is so accustomed to weird picture books that she doesn’t bat an eye.

Yard sale season has begun in downtown Toronto! On Saturday, we picked up these three fine volumes, along with Michele Landsberg’s Guide to Children’s Books and Human Voices by Penelope Fitzgerald, for a remarkable $1.25. The Apple by Dick Bruna is as strange and visually appealing as anything Dick Bruna ever published; we love Sunshine by Jan Ormerod, which we’ve had out of the library a number of times (and I am particularly fond of the mother who sleeps/reads in bed until the last possible second, and then runs around the house getting ready in a frenzy. I feel as though I know her very well…); and The Little Steamroller by (the!) Graham Greene is amazing! A picture book this might be, but it’s absolutely Graham Greene, complete with a criminal gang smuggling gold from Africa and terrible English weather. Totally weird, but Harriet is so accustomed to weird picture books that she doesn’t bat an eye.

May 2, 2013

Everything Rustles by Jane Silcott

In her book How To Be A Woman, Caitlin Moran talks about “the common attitudinal habit in women that we’re kind of…failing if we’re not a bit neurotic,” and certainly fiction, memoir, film and television abound with women unabashedly celebrating this “success”. But it all gets a bit tiresome, really, this idea that women are never more remarkable than when they’re twenty-three and totally fucked up (or thirty-three, or forty-three, but still totally fucked up). I’ve really got a thing for women who’ve learned a thing or two, particularly a thing beyond how to hit rock-bottom and make a bizarrely lipsticked corpse. Please do see my list of Great Canadian Non-Fiction for an idea of what I’m talking about, essay collections by amazing writers with experiences to recount and distance and maturity enough to reflect on those experiences. I maintain that it’s really possible for a person to grow up, to get a handle on things, to have kept a close enough eye on the world around them that they have something to teach the rest of us.

In her book How To Be A Woman, Caitlin Moran talks about “the common attitudinal habit in women that we’re kind of…failing if we’re not a bit neurotic,” and certainly fiction, memoir, film and television abound with women unabashedly celebrating this “success”. But it all gets a bit tiresome, really, this idea that women are never more remarkable than when they’re twenty-three and totally fucked up (or thirty-three, or forty-three, but still totally fucked up). I’ve really got a thing for women who’ve learned a thing or two, particularly a thing beyond how to hit rock-bottom and make a bizarrely lipsticked corpse. Please do see my list of Great Canadian Non-Fiction for an idea of what I’m talking about, essay collections by amazing writers with experiences to recount and distance and maturity enough to reflect on those experiences. I maintain that it’s really possible for a person to grow up, to get a handle on things, to have kept a close enough eye on the world around them that they have something to teach the rest of us.

Though to get a handle on things, of course, is not to have it all figured out, or to ever stop asking questions, to have all the answers. Everything Rustles, Jane Silcott tells us in her book’s introduction, came about by accident. She didn’t know that she was writing a book, but instead, “I was just trying to find out what I thought about things.” She is writing from a threshold, just beyond her child-bearing years but with age not set in yet (though set in, it will–it all begins with that first twist of the knee whilst skiing). In her essay “Threshold”, Silcott writes, “As I head off to exercise class, drinking a glass of soy milk before I go, I think of girdles, cigarettes and gin. Why was I born into this relentlessly earnest time of herbal remedies and yoga classes? Why can’t I take advantage of stimulants and supportive underwear?”

The essays in this collection are diverse in structure and approach, but have in common Silcott’s attention to language, her curiosity, and sense of humour. She writes about what she’s learned and unlearn from aging; about her experiences as clinical teaching associate, model and guide to nurses and doctors learning how to conduct pelvic exams; about love, sex, and marriage, just what attracts two people; about family, about switching her kitchen table from round to rectangular and how it changed mealtimes and their family dynamics. She writes about fears; about her fears of passing her fears to her daughter; about encounters with friends and strangers, and her questions about what these mean. She writes about writing, about using life itself in order to understand how stories work; about losing her parents; about losing friends. I loved “Lanyard”, about her experiences teaching business English: “When I work at places with lanyards, I put on makeup and fuss with my hair.” She writes about letting her children go out into their own lives.

Everything Rustles is a high-literary version of Nora Ephron’s I Feel Bad About My Neck. These are essays that require close attention, which twist and turn away from where you think they’ll go. Not easy reading, but reading that is rich and rewarding. These stories of what Jane Silcott thinks about things deliver a vivid perspective of the world and life itself, and they’re a celebration of strength, wonder and learning.

May 1, 2013

Summer has arrived

Sweet Fantasies is open for the season. I suspect they’ll be seeing a lot of us over the next few months…

Sweet Fantasies is open for the season. I suspect they’ll be seeing a lot of us over the next few months…

In related good news, see here.

May 1, 2013

When We Were Good by Suzanne Sutherland

We’ve come a long, long way, Suzanne Sutherland and I. We became familiar with one another after Harriet was born, and I used to the wander the neighbourhood in quiet desperation, baby strapped to my chest. Suzanne was bookseller supreme at my beloved local, one of the friendly faces that brightened my days back then. She liked to write, I knew, and I happened to be in the store the first time she received an acceptance to a literary magazine–I think it was Descant. She didn’t know I was editor of 49th Shelf when she started uploading amazing reading lists to the site, lists which confirmed that Suzanne Sutherland is undeniably cool (in addition to being lovely). Eventually, I became less desperate, Harriet got too big for her carrier, Suzanne got a book contract, and then moved on to a new job in editorial at Groundwood Books. I continue to adore the Book City staff, but I’ve never completely got over Suzanne leaving.

We’ve come a long, long way, Suzanne Sutherland and I. We became familiar with one another after Harriet was born, and I used to the wander the neighbourhood in quiet desperation, baby strapped to my chest. Suzanne was bookseller supreme at my beloved local, one of the friendly faces that brightened my days back then. She liked to write, I knew, and I happened to be in the store the first time she received an acceptance to a literary magazine–I think it was Descant. She didn’t know I was editor of 49th Shelf when she started uploading amazing reading lists to the site, lists which confirmed that Suzanne Sutherland is undeniably cool (in addition to being lovely). Eventually, I became less desperate, Harriet got too big for her carrier, Suzanne got a book contract, and then moved on to a new job in editorial at Groundwood Books. I continue to adore the Book City staff, but I’ve never completely got over Suzanne leaving.

I’m overjoyed, however, to finally get my hands on her book, the YA novel When We Were Good. My experience of children’s literature is primarily through Harriet, and so I’m not so up on YA. But I do love Toronto books, so I was excited to read this one. More specifically, it’s a coming-of-age book about Toronto at the beginning of the new millennium, just when I was coming of age in the very same neighbourhoods, albeit quite belatedly (and truth be told, I’m still not done).

I am so pleased that my blurb appears on the book’s back cover (my name is on a book!!). It says, “Finally, the definitive Toronto novel for a new generation of readers. Suzanne Sutherland’s When We Were Good is an ode to the city, to music, and to falling in love.”

Check out Suzanne’s latest awesome list, Books That’ll Mess You Up Good.

May 1, 2013

Picture Book Happenings

On Sunday, we had the pleasure of attending the launch for Andrew Larsen’s latest book In the Tree House (which you might recall that I adored). I do feel sorry for literary types who don’t know what they’re missing in picture book launches. The reading is never boring, they skip the Q&A (yay!) and snacks are always excellent–at this one, we got yellow star cookies, rice crispie squares and delicious lemonade. We saw lots of friends there, and had a wonderful afternoon. It was wonderful to celebrate with Andrew, who is a truly fantastic person. If you don’t know his work yet, I’d encourage you to check out any of his books. You will be enchanted.

On Sunday, we had the pleasure of attending the launch for Andrew Larsen’s latest book In the Tree House (which you might recall that I adored). I do feel sorry for literary types who don’t know what they’re missing in picture book launches. The reading is never boring, they skip the Q&A (yay!) and snacks are always excellent–at this one, we got yellow star cookies, rice crispie squares and delicious lemonade. We saw lots of friends there, and had a wonderful afternoon. It was wonderful to celebrate with Andrew, who is a truly fantastic person. If you don’t know his work yet, I’d encourage you to check out any of his books. You will be enchanted.

I also have a new picture book review online at Quill & Quire for In Lucia’s Neighbourhood by Pat Shewchuk and Marek Colek. While it’s not a perfect book, it’s a remarkable one, and an essential addition to the library of any urban picture book lover.

I also have a new picture book review online at Quill & Quire for In Lucia’s Neighbourhood by Pat Shewchuk and Marek Colek. While it’s not a perfect book, it’s a remarkable one, and an essential addition to the library of any urban picture book lover.

There is much to love about In Lucia’s Neighborhood, the picture book by Pat Shewchuk and Marek Colek that grew out of the duo’s celebrated animated short film Montrose Avenue. Opening with an epigraph from Jane Jacobs’ The Death and Life of Great American Cities (“The ballet of the good city sidewalk never repeats itself”), the story goes on to show how the urban theorist’s sidewalk ballet is enacted every day on one street in Toronto’s Little Portugal neighbourhood. (Read the rest here)

April 29, 2013

On Passing Judgement

My favourite response to my “Stick Rage” post at Bunch Family was the person who wrote, “Save it for your personal blog, Kerry Clare. Clearly, you’re about judgement and singling people out, not bringing families together.” I laughed. “Clearly, you’re about judgement…” Man, I thought, you don’t even know. Because I am all about judgement. Really. This is why some people find me amusing to converse with, and I don’t know that I’m so singular in this characteristic because the people I like to converse with are pretty “judgy” as well. In the best way, of course, by which I mean that they are funny, don’t suffer fools gladly, have ideas and opinions and no qualms about expressing them.

This may be why I’ll never make it as a parenting blogger. “The world is so judgemental already. Let’s stop judging. Everyone is entitled to their opinion and actions.” This was a comment on a recent post at the blog Playground Confidential, and when I read it, I thought (and judged), “How positively uninteresting it must be to go about the world with that perspective.” I am troubled by this idea that women in particular must amass whilst cooing soft noises of mutual support and approval, because who actually does this? (Speaking of parenting blogs, I am also troubled by the sheer number of people who pass their lives by littering the the internet with sponsored blog posts about how much their domestic lives are assisted by Hamburger Helper, but that’s a judgement for another day.) Sure, everyone is indeed entitled to their opinions and actions (but no! even this isn’t true!) but therefore aren’t I perfectly entitled to find you an asshole, or an idiot? I’m even entitled to say as much. And you’re more than welcome to judge right back, but please don’t do so on the basis of me being judgemental because it’s an awfully terribly tiresome feedback loop and I don’t even care.

What bothers me the most about this whole “Let’s stop judging” approach is its dishonesty. It is a rare person who ever really pulls this off, and the rest of us are just whispering judgements to our friends behind your back. I’m not sure this is necessarily kinder than making pronouncements aloud. Now of course, to judge and to be vicious are not necessarily the same thing and the distinction between the two is important. But it’s a eye of the beholder thing, really, and haven’t we talked about this in terms of book reviewing a hundred thousand times? I’ve tried to work around this as a book reviewer by not reading or reviewing books I know I’m programmed to respond to with judgement instead of an open mind. It’s not worth my time, and neither the world’s to pollute it with my vitriol (this post and the one about stick families, of course, excluded. And can you tell that I am nine months pregnant? I have never been such a judger-naut! Or used so many italics!).

So this is the reason that I haven’t read Drunk Mom by Jowita Bydlowska, though certainly it’s a book I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about. As someone who has made a thing of writing honestly about motherhood and expressing the truth of my own difficult experiences with its early days, certainly I’m intrigued by Bydlowska’s project and by my own ambivalent response to it. And I was also intrigued by Sarah Hampson’s interview with Bydlowska, which dared to pose difficult questions and not just those that had been approved by Bydlowsk’s publicist. The interview was interesting, which is more than you can say about the interviews with her that have appeared elsewhere with their polite questions and predictable answers. I’m not even sure that it was journalistically troubling, because good interviewers are always very much a character in the story they’re telling. The problem, I suppose, would be if Hampson had been dishonest with Bydlowska in their conversation, had hoodwinked her somehow, but it shouldn’t be a problem that Hampson was honest in how she responded to the book. This book for which Bydlowska’s own honesty and bravery have been so celebrated; why is another writer meant to just shut up and be polite?

I similarly appreciated Lisan Jutras’ review of the book in The Globe on Saturday. I didn’t find the review to be judgemental, but found instead that Jutras approached the book (as well as her response to it) with questions instead of conclusions (and herein is the distinction between a critical review and a cruel one, I think), that she broadened the conversation, which is precisely what a book review is meant to do. (More italics. I can’t stop). She questions this reflexive response of terming female memoirists as “brave”, she questions her own fascination with Bydlowska’s story and her discomfort with this.

“I’m torn about this book,” is something that somebody wrote to me the other day, and I’m having trouble discerning how any reader could not be. It is a troubling, fascinating book that is worthwhile for the questions it raises, I think, and I find it odd that we would judge anybody for asking them. To ask those questions is not to be lacking in compassion, but it’s to be curious about a book, about the world. (I also think the whole, “But the reviewer doesn’t even mention the prose style” is a little disingenuous. Drunk Mom is not about its prose, or at least its marketers don’t think it is, so I think we can be forgiven for not playing along with that game. Very few of us stare at car accidents for aesthetic reasons. I also recognize that this book is meant to be intended to help and support those suffering from addiction, but then what are we meant to do with it, those of us who aren’t undergoing such struggles? Other than not read it. A book has to exist on its own terms and be more than a life preserver.)

Bydlowska is in no way unique for being a woman who has been publicly rebuked for her mothering skills. Just yesterday, I read the fantastic essay “The Meaning of White” by Emily Urquhart about her experience as a mother whose child was born with albinism, and I was aghast by the rage expressed in the comments: apparently Urquhart is hijacking her daughter’s story, is ableist, is making something out of nothing, is a white supremacist. There is something troubling about this mass jumping on the hate-train that almost makes me want to rethink my so-called judgy life, but then I’ve gone and judged already–we already know that internet commenters are morons anyway and are really none of anyone’s concern, not mine, nor Emily Urquhart’s, or Jowita Bydlowska’s either.

My point is that when you tell your story, people are allowed not to like it. And when that story is you, judgement is going to come into play when people don’t like it, even if you do something shrewd like decide your book is an “autobiographical novel”. “The main character in this book is a such a kind of person and what is the author’s intention in representing herself this way” is a legitimate line of thinking to pursue for a reader/critic, [albeit not a great basis for critical assessment] but we’re all avoiding that conversation for fear of being impolite. We’re avoiding so many conversations for the sake of politeness, actually, and I’m not sure our books are any better for it. I’d far rather read an honest review that posed provocative questions than one that sang the praises of bravery as a singular reason for any book to be.