March 26, 2015

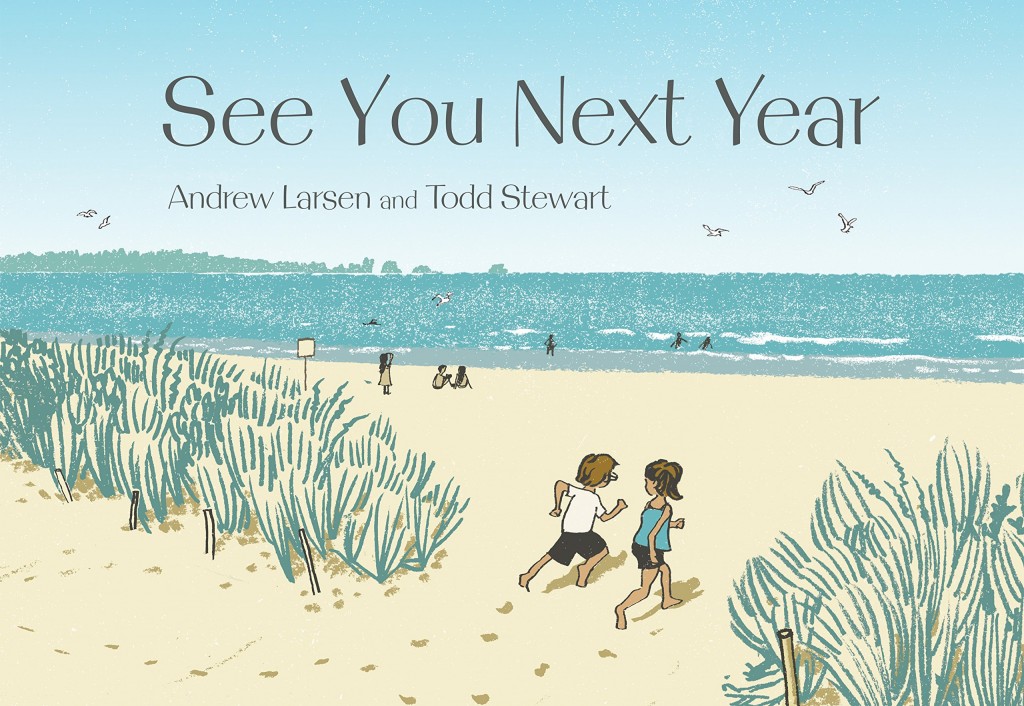

See You Next Year by Andrew Larsen and Todd Stewart

Our first Andrew Larsen book was The Imaginary Garden, which was a Best Book of the Library Haul almost 4 years ago. Since then I’ve raved about his other books, including In the Tree House and Bye Bye Butterflies, and even more important (though not more important than that he was a finalist for the TD Children’s Literature Award in November), Andrew has become my friend. We met first at the library, obviously, and because we live in the same neighbourhood, we get to walk together to school pick-up when circumstances are fortuitous. I enjoy his company immensely, and have been oh so looking forward to his new book, See You Next Summer, illustrated by Todd Stewart. And happily, it’s everything I was hoping it would be.

It’s a simple story celebrating ordinary wonders, the things we can count on, articulated in the perfect, slight-wistful child’s eye view that Larsen is becoming known for. And it’s a summer book, about a girl whose family returns to the same beachside motel for their vacations every year (“I call it our cottage. But it’s not really a cottage.”—and I appreciate that Larsen’s stories often reflect more modest economic realties, the kind we’re more familiar with in our family). It’s a place where nothing ever changes. On Sunday morning, the girl watches the tractor rake the beach, on Monday nights they go into town to the bandstand where a band plays, and on Tuesday it’s foggy, and so on. Though one thing is different this year—she’s made a new friend. They write postcards together, play in the waves, dig in the sand and roast marshmallows in a bonfire on the beach. And that’s it really. There is a twist at the end that’s really lovely, but it does nothing to counter the constancy of the narrative, to undermine the girl’s faith in sure things. Which I love—this simple celebration of rituals we build our lives around, an articulation of faith a bit less cloying than, say, The Carrot Seed. A affirmation that there are good things in the world, things to count on. Sure, the real world is going to come along and challenge the girl’s faith at some point, because that’s what growing up is, but not everything will get broken. Moreover, in this ever changing world in which we live in (to quote a Beatle), it really is the present moment that matters, and Larsen captures it splendidly—the confidence of the child who knows what she knows, whose confidence of her place in the universe is unquestioned, unshaken. It’s the sort of security that every child deserves to grow up amidst.

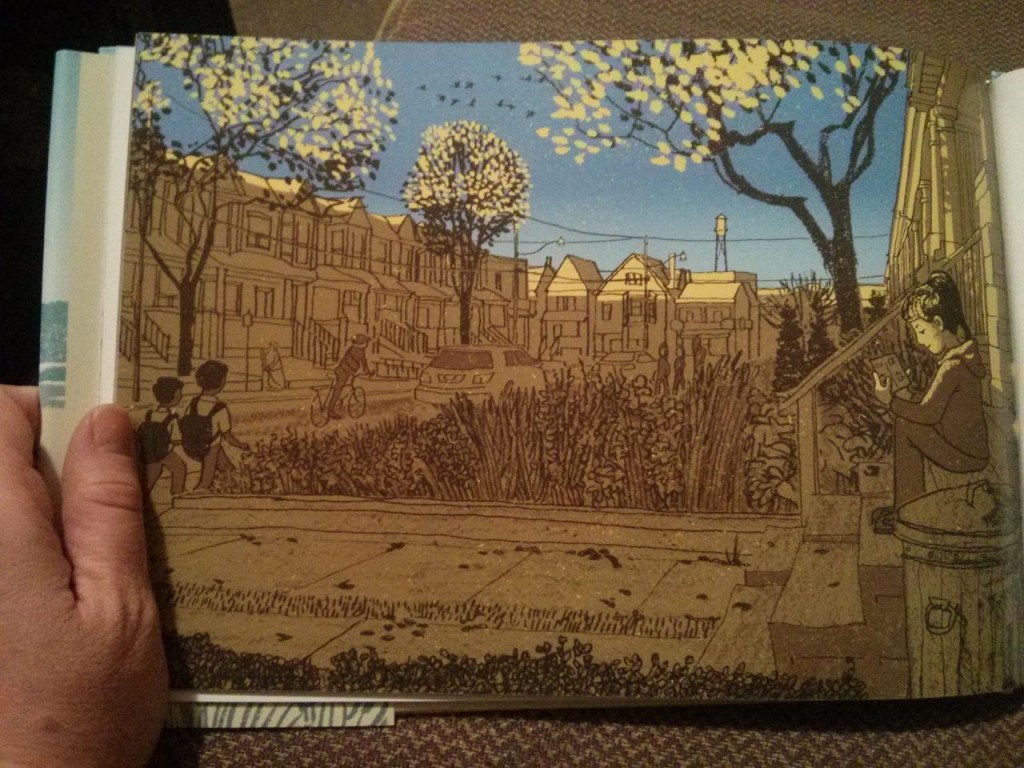

Todd Stevens’ illustrations are completely enthralling due his fascinating use of light. See the porch light above (with the red sunset just on the horizon), and the sunrise over the city with half the street still in shade, and elsewhere in the book, the shadow from beach umbrellas, the shadow of evening in later afternoon, how a streetlight shines through fog, the lights of the campfire, from shooting stars, the silhouette of the friend waving against the sun as the girl watches him through the back window of the car as her family begins their journey home. (On the very last page of the book, there is a light switch. I find this most significant, of course). And it occurs to me that his use of light is perfect to show the passage of time during a period in which nothing changes—Virginia Lee Burton pulled off a similar trick with The Little House. Suggesting that things are actually changing all the time, the world around us ever in flux, but that all change is part of a cycle. The images adding an additional layer of depth and poignancy to Larsen’s tale.

March 25, 2015

A Year of Days by Myrl Coulter

The title and premise of Myrl Coulter’s essay collection, A Year of Days, bring to mind the quote by Annie Dillard: “How we spend our days is how we spend our lives.” But considering its inverse, Coulter’s essays examining the shapes of our lives by the days a life comprises, the singular days upon which time hangs its hat, and that become our markers from year to year to year. February, birthdays, the August long weekend, Thanksgiving, Halloween. In a life forever changing, it’s these days that are ever constant, to be counted on, and the seasons too, cycles returning every year, and it’s only you who has become so different. Our connections to these days are visceral—sometimes in anticipation, or anxiety, or happiness, or grief. And it’s this viscerality (a word she coins) as well as the days themselves that are points of departure for the essays in this book. New Years Day, for the first essay, a calm day, the chance to start again. All the while she’s mourning the death of her mother, irrevocably lost.

The title and premise of Myrl Coulter’s essay collection, A Year of Days, bring to mind the quote by Annie Dillard: “How we spend our days is how we spend our lives.” But considering its inverse, Coulter’s essays examining the shapes of our lives by the days a life comprises, the singular days upon which time hangs its hat, and that become our markers from year to year to year. February, birthdays, the August long weekend, Thanksgiving, Halloween. In a life forever changing, it’s these days that are ever constant, to be counted on, and the seasons too, cycles returning every year, and it’s only you who has become so different. Our connections to these days are visceral—sometimes in anticipation, or anxiety, or happiness, or grief. And it’s this viscerality (a word she coins) as well as the days themselves that are points of departure for the essays in this book. New Years Day, for the first essay, a calm day, the chance to start again. All the while she’s mourning the death of her mother, irrevocably lost.

“As soon as she was gone from this earth, I felt an overwhelming need for more of her. I had to find her again. But how do you find someone after they’re gone for good? That’s where viscerality comes in handy. My viscerality took me on a trek into the years my mother and I had spent on the planet, both together and apart.”

Like many of my favourite essay collections though, the thematic here link is tangential. Even the essays themselves embark upon wild twists and diversions. Coulter’s essays fit Susan Olding’s definition of the genre, in which she writes, “Partaking of the story, the poem, and the philosophical investigation in equal measure, the essay unsettles our accustomed ideas and takes us places we hadn’t expected to go… We start out learning about embroidery stitches and pages later find ourselves knee-deep in somebody’s grave.” And with the book as a whole, you start out expecting a book that’s a kind of calendar, only to find that Myrl Coulter has cast her net so very wide.

And what has she captured? The magnificent frigate bird swooping over the sea, seen from the hotel where Coulter partakes in a Mexican sojourn. How does one capture a sunset? Winter as an analogy for her mother’s dementia, casting their family into a season of darkness. An essay on Valentines, and hearts real and metaphoric, and perforated hearts, and the difficulty of cutting while left-handed with right-handed scissors. On Easter, and Easter Island, and Easter Bunnies, and the lies we tell our children for the sake of magic. I love this essay’s ending: “Nostalgia lives in the impossible notion that we can start again… I suppose that makes nostalgia a little like repentance.”

I loved the essay, “Gym Interrupted, Again,” in which Coulter contemplates the work-out clothing she’s acquired over decades, considering her high school PE uniforms, ’80s aerobic sweatbands, expensive running shoes, bagging jogging pants, running tights, and all the changing fashions of fitness and its attire, and the body, the one constant (though in itself, ever changing). “But one relationship we have that isn’t interrupted, at least until the day it ends forever, is the one we have with our bodies. They are the houses we live in.”

She writes about her discomfort with Mother’s Day and Father’s Day, built on idealized notions that often please no one. About the May long weekend, and her surprise that golfing has become part of her life, articulating what she loves about the sport in a way I found fascinating. “Lakes I Have Known” is summer and swimming and floating free. “Cornocopia Soup,” sort of about Thanksgiving, but essentially a recipe for making Chicken Soup over two days, about loneliness and soup-making as therapy, and it made me so hungry. “Survival Gear,” which riffs on Halloween and costumes, and our selves as costumed beings, and ends with, “Words and pictures—survival gear for our stories.”

“Wearing Black” on funerals and mourning, and the surprising “Music on the Hill” about the ins-and-outs of the Edmonton Folk Music Festival, and its peculiar and particular rituals recurring year after year, and she writes about these experiences while numbed by grief, after her mother’s death, of “my distraction year” when “my inner music stopped.” The collection ends with the weird and wonderful “Current Crossings” about Edmonton’s High Level Bridge and its various modes of crossing. Back and forth, back and forth, the traffic flowing like time is, and bridges are metaphors for so many things—for the possibility of connection, for how here we are between one thing and another, or the bridge itself as a year and every journey across it is so very different.

If Myrl Coulter’s name sounds familiar, it may be because she was a contributor to The M Word, her essay actually an excerpt from her phenomenal book, The House With the Broken Two. While Coulter’s complex relationship with her mother is an important aspect of her memoir, it’s considered more obliquely here. A Year of Days is not so much a book about grief as a book that’s haunted by Coulter’s mother’s spirit. As the whole world might seem to be after a loss, I’d suppose, the collection creating some order from the pieces that are left.

March 25, 2015

Pickle Me This: The Digest

You’ll see up in the top of the right-hand column that I’ve started a Pickle Me This newsletter, which will be referred to with the far more literary title of “Digest.” The Pickle Me This Digest will be the best of the blog delivered each month to your inbox with a smattering of book reviews, picture book reviews, and other features. I know that fewer people are visiting blogs on a regular basis these days, and instead come to specific posts via social media links, which is all fine and well, but I thought the Digest might be a great resource for anyone who’d like to stay better in touch on a regular basis.

You’ll see up in the top of the right-hand column that I’ve started a Pickle Me This newsletter, which will be referred to with the far more literary title of “Digest.” The Pickle Me This Digest will be the best of the blog delivered each month to your inbox with a smattering of book reviews, picture book reviews, and other features. I know that fewer people are visiting blogs on a regular basis these days, and instead come to specific posts via social media links, which is all fine and well, but I thought the Digest might be a great resource for anyone who’d like to stay better in touch on a regular basis.

Even better? Anyone who signs up for The Pickle Me This Digest in the next month will have their name entered in a draw to win a copy of the essay anthology I edited, The M Word: Conversations About Motherhood, which was published last year by Goose Lane Editions. Mother’s Day is coming up soon, so the book is timely. And if you have a copy already? Well, why not pass your extra copy along to a friend? As Deborah Ostrovsky wrote in the Fall 2014 issue of Herizons magazine, “… You won’t keep this book; you’ll pass it on to friends whose current vocation is changing diapers, or to friends who want a child, and those who don’t.”

Even better? Anyone who signs up for The Pickle Me This Digest in the next month will have their name entered in a draw to win a copy of the essay anthology I edited, The M Word: Conversations About Motherhood, which was published last year by Goose Lane Editions. Mother’s Day is coming up soon, so the book is timely. And if you have a copy already? Well, why not pass your extra copy along to a friend? As Deborah Ostrovsky wrote in the Fall 2014 issue of Herizons magazine, “… You won’t keep this book; you’ll pass it on to friends whose current vocation is changing diapers, or to friends who want a child, and those who don’t.”

If you’ve already signed up for the newsletter, I’ll add your name to the draw. And as ever, thank you for your support of Pickle Me This!

March 25, 2015

After Birth: Redux

Redux is the wrong word. I haven’t stopped thinking about After Birth since I finished reading it last week. This morning I had the most interesting conversations with a woman who is a newish friend of mine (and don’t you find that new friends become more and more precious as one gets older?) with whom I’ve had the pleasure of so much company over the past few months while she’s been on maternity leave with her third child. Fortuitously, her house is a stone’s throw from mine, her son and Harriet are passionate friends, she’s so ridiculously smart and funny, and she just read After Birth. (I wish every woman a friend with whom to discuss After Birth.) So this morning we sat around my living room while my baby mauled her baby, and we talked about the book, how it made us both uncomfortable. Because, I think, I said, trying to put my finger on it, it doesn’t tidy up. Nothing is resolved, it moves is a circle. It is an unsatisfying book, which I mean as the highest literary praise. Like another fine book, Harriet the Spy, After Birth is about a female person who doesn’t change, who doesn’t stop ranting, who doesn’t stymy her anger. And we need this anger, I think—to seize on its power—, and we need this insistence on circuity, as opposed to the narratives we’re being sold most of the time about how we should tuck our anger and our lives, our selves, inside tiny tidy boxes. We’re being sold narratives of binary—breast and bottle, wohms and sahms. Just today, there is an online fracas because someone wrote an inane justification for stay-at-home-momming (don’t seek it out or read it. Nothing new under the sun. Argument is best articulated and refuted here). The writer articulating her lifestyle in opposition to somebody else’s, and I just though, how boring. I thought about the writer’s argument in contrast with the vibrant thinking I was a part of this morning, and all I could think of to say to her is, I wish for you the freedom to live your life on your own terms. Not to care anymore. Not to have to purport to have all the answers, or believe there even needs to be an answer. We’re all cobbling together our pieces, and the patterns don’t have to be the same. And yes, I wish for the public conversations about motherhood to be like the ones we’re having in private: the passionate, expansive ones that are challenging, rich and about the whole wide world.

Redux is the wrong word. I haven’t stopped thinking about After Birth since I finished reading it last week. This morning I had the most interesting conversations with a woman who is a newish friend of mine (and don’t you find that new friends become more and more precious as one gets older?) with whom I’ve had the pleasure of so much company over the past few months while she’s been on maternity leave with her third child. Fortuitously, her house is a stone’s throw from mine, her son and Harriet are passionate friends, she’s so ridiculously smart and funny, and she just read After Birth. (I wish every woman a friend with whom to discuss After Birth.) So this morning we sat around my living room while my baby mauled her baby, and we talked about the book, how it made us both uncomfortable. Because, I think, I said, trying to put my finger on it, it doesn’t tidy up. Nothing is resolved, it moves is a circle. It is an unsatisfying book, which I mean as the highest literary praise. Like another fine book, Harriet the Spy, After Birth is about a female person who doesn’t change, who doesn’t stop ranting, who doesn’t stymy her anger. And we need this anger, I think—to seize on its power—, and we need this insistence on circuity, as opposed to the narratives we’re being sold most of the time about how we should tuck our anger and our lives, our selves, inside tiny tidy boxes. We’re being sold narratives of binary—breast and bottle, wohms and sahms. Just today, there is an online fracas because someone wrote an inane justification for stay-at-home-momming (don’t seek it out or read it. Nothing new under the sun. Argument is best articulated and refuted here). The writer articulating her lifestyle in opposition to somebody else’s, and I just though, how boring. I thought about the writer’s argument in contrast with the vibrant thinking I was a part of this morning, and all I could think of to say to her is, I wish for you the freedom to live your life on your own terms. Not to care anymore. Not to have to purport to have all the answers, or believe there even needs to be an answer. We’re all cobbling together our pieces, and the patterns don’t have to be the same. And yes, I wish for the public conversations about motherhood to be like the ones we’re having in private: the passionate, expansive ones that are challenging, rich and about the whole wide world.

March 23, 2015

Where I Find the Time to Read

I read a lot. I read for a living, and I read to save my life, and, “Where do you find the time to read?” is a question that continues to baffle me. It’s like being asked where I find the air to breathe. The time, like the air, is out there in abundance, and having children hasn’t changed that. It just means I have to be creative in finding a way to make that time my own.

I read a lot. I read for a living, and I read to save my life, and, “Where do you find the time to read?” is a question that continues to baffle me. It’s like being asked where I find the air to breathe. The time, like the air, is out there in abundance, and having children hasn’t changed that. It just means I have to be creative in finding a way to make that time my own.

The following is a list of ordinary occurrences disguising excellent opportunities to steal a moment with a book.

- Extended Breastfeeding: Of the many benefits of breastfeeding, the time to read in is paramount. Once you’ve mastered holding a book open with one hand, it’s effortless, and oh so efficient—nourish a baby and your mind in a single shot. When my first daughter finally weaned at age 2 ½, I so mourned the loss of reading time that I had to have another baby.

Before Bed: Every night, there is a window of sometimes up to ten minutes between the moment my head hits the pillow and when the baby awakes, and so I read then. And when the baby does awake, I breastfeed her. (See previous point.)

Before Bed: Every night, there is a window of sometimes up to ten minutes between the moment my head hits the pillow and when the baby awakes, and so I read then. And when the baby does awake, I breastfeed her. (See previous point.)

- Weekend lie-ins: Obviously, I don’t get out of bed in the mornings. Would you? On Saturday and Sunday mornings, there is always time to get a chapter in before I return to the vertical life, and if I stay in bed long enough, somebody probably will bring me a cup of tea. And then I don’t have to get up until I’ve drunk it.

Walking: Walking while reading is walking the one risky behaviour I indulge in on a regular basis. Doing it while pushing a stroller is even more reckless, I realize, but sometimes one has to live on the edge. Also, I could make it to kindergarten and back with my eyes shut, so there’s no harm in doing with text in front of my face.

Walking: Walking while reading is walking the one risky behaviour I indulge in on a regular basis. Doing it while pushing a stroller is even more reckless, I realize, but sometimes one has to live on the edge. Also, I could make it to kindergarten and back with my eyes shut, so there’s no harm in doing with text in front of my face.

- At the playground: I will argue that reading at the playground is not entirely the opposite of being present for my children, mostly because there are only so many mud-pies I can pretend to gleefully devour. Also, every time they look up at the bench and see me reading there, I’m increasing their own chances of being readers by setting a good example. Everybody wins.

During interruptions: Basically, I find the time to read by always having a book in my bag. Sometimes two. And this means that when my husband takes the kids to the bathroom after a restaurant meal, I can finish a chapter along with the dregs of my tea.

During interruptions: Basically, I find the time to read by always having a book in my bag. Sometimes two. And this means that when my husband takes the kids to the bathroom after a restaurant meal, I can finish a chapter along with the dregs of my tea.

- Sitting alone in restaurants by myself: And other times, I forfeit the husband and kids altogether, and take myself out for a chai latte and oversized cookie, or even an entire lunch, and read the entire time. Cultivate your own company, is what I mean, and you will get so much reading done.

- In waiting rooms: As a parent with a book in her bag, there is nothing more luxurious than having to wait for appointments while the children are asleep in their strollers or in the care of somebody else. I’ve spent some of the best afternoons of my life in recent years reading for solid blocks of time at the passport office, my doctor’s, or the dentist.

- While flossing: Regarding the dentist, I have never before been so attentive to dental hygiene. I’ve become a vigilant flosser since I learned to floss and read, which is a skill involving holding open a book with my feet. I do this daily. For ten to twenty minutes at a time.

- In the bathroom: Also, for ten to twenty minutes at a time. My digestive system is getting a bad reputation. But there is a door that locks and a stack of books nearby—why would I ever leave?

Pancakes: I don’t spend all my time avoiding my family, however. Every Sunday, I make whole-wheat banana pancakes from scratch, which sounds selfless and well-meaning until I explain that once the batter is mixed, I pull out what’s left of the Saturday paper, flipping the pancakes between articles. (“Go away. Mommy is cooking.”)

Pancakes: I don’t spend all my time avoiding my family, however. Every Sunday, I make whole-wheat banana pancakes from scratch, which sounds selfless and well-meaning until I explain that once the batter is mixed, I pull out what’s left of the Saturday paper, flipping the pancakes between articles. (“Go away. Mommy is cooking.”)

- But not at the table. Unless it’s breakfast or lunch…We don’t permit reading at the table at our house, because meals are a time for togetherness. We bend the rules for breakfast and lunch though, because bendy rules are useful for teaching flexibility. And because tables are so useful for having the Saturday paper spread across.

March 19, 2015

The Bus Ride by Marianne Dubuc

We’re becoming big fans of Marianne Dubuc’s books at our house, having enjoyed In Front of My House and Animal Masquerade. You will recall that picking up the latter title resulted in our entire family eventually assembling on the couch, gathering together captured by the book’s magic, and laughing hysterically at the surprises and absurdity. Dubuc’s latest book, The Bus Ride, similarly engages and surprises, and while it’s is very loosely based on the Little Red Riding Hood narrative, a more fitting descriptive for the story would be “curiouser and curiouser.”

We’re becoming big fans of Marianne Dubuc’s books at our house, having enjoyed In Front of My House and Animal Masquerade. You will recall that picking up the latter title resulted in our entire family eventually assembling on the couch, gathering together captured by the book’s magic, and laughing hysterically at the surprises and absurdity. Dubuc’s latest book, The Bus Ride, similarly engages and surprises, and while it’s is very loosely based on the Little Red Riding Hood narrative, a more fitting descriptive for the story would be “curiouser and curiouser.”

The Bus Ride is the story of a little girl’s first ride along on a city bus to visit her grandmother’s house. Her mother sees her off at the bus stop, ensuring she’s got a snack and a sweater in case she gets cold. And from there the rest of the story is of the bus ride, the bus’s interior each two-page spread. Passengers embark at the front doors and alight through the back. The little girl narrates what she sees in a sentence or two, although the real story is happening in Dubuc’s illustrations. A cat is knitting a scarf that grows ever-longer, a mouse is reading a tiny book, a family of rambunctious moles (I think?) climbs on board and end up swinging from the overhead bars (and one chews on a piece of gum he finds on the floor). A family of wolves boards the bus and the little girl makes friends with the wolf-boy who’s about her age—they share her cookies. A sleepy sloth snoozes the ride away. Someone’s hiding behind a newspaper whose headlines are ever-changing and reference what’s going on the pictures. I admired in the stolid bear in his big blue boats.

They pass through the forest, through a tunnel. Children run amuck. The fox keeps sleeping. The owl woman in the hat seems quite uncomfortable, and characters keep turning up in different places. The turtle gets nervous and hides in his shell. A wannabe pickpocket—a fox, of course—boards the bus, and and the little girl helps to divert a crime. And what is the beaver carrying inside his really big box?

They pass through the forest, through a tunnel. Children run amuck. The fox keeps sleeping. The owl woman in the hat seems quite uncomfortable, and characters keep turning up in different places. The turtle gets nervous and hides in his shell. A wannabe pickpocket—a fox, of course—boards the bus, and and the little girl helps to divert a crime. And what is the beaver carrying inside his really big box?

While The Bus Ride is first a story of one girl’s first independent journey into the world, it’s fundamentally a story of how interesting the world is and how fascinating it is to be in the midst of it all. At the end of the bus ride, the little girl reflects on all the stories she has to tell her grandmother now. Hers is an apprenticeship in narrative, but it is for the reader as well, who assembles her own story based on the curious scenes depicted in Dubuc’s illustrations, which are detailed and accessible, appealingly rendered in pencil crayon. And like all the very best picture books, it’s completely different with every encounter.

March 19, 2015

A sign of spring

I love the springs that arrive like this, like an unexpected gift instead of something long overdue. Spring is not quite here yet, but it’s making itself known, the way the green of a crocus appears like a dot in the dirt (and the way a tooth first appears, a dot of white on a baby’s gum—this is my metaphor lately). There are no leaves on the trees and the air still has a chill, but look how the sky is blue, the snow is gone, and our household’s sheets are drying on the line.

I love the springs that arrive like this, like an unexpected gift instead of something long overdue. Spring is not quite here yet, but it’s making itself known, the way the green of a crocus appears like a dot in the dirt (and the way a tooth first appears, a dot of white on a baby’s gum—this is my metaphor lately). There are no leaves on the trees and the air still has a chill, but look how the sky is blue, the snow is gone, and our household’s sheets are drying on the line.

Though the surest sign that it isn’t spring (yet) is how cold were my hands after hanging out the sheets. Soon though…

I was inspired to hang out the sheets from Sarah’s blog post about hanging out her washing (and her comments on the magical high-up washing lines with pulleys that need to be hauled in and out—I dream of these, though they terrify me also. What if something comes loose and my pillowcase falls down six stories, lost forever). It strikes me what a literary thing is clothes on the line—indeed, as I was hanging the sheets this morning, the “Grandma hanging washing on the clotheslines to be dried” line kept bouncing through my head from Peepo.

I was inspired to hang out the sheets from Sarah’s blog post about hanging out her washing (and her comments on the magical high-up washing lines with pulleys that need to be hauled in and out—I dream of these, though they terrify me also. What if something comes loose and my pillowcase falls down six stories, lost forever). It strikes me what a literary thing is clothes on the line—indeed, as I was hanging the sheets this morning, the “Grandma hanging washing on the clotheslines to be dried” line kept bouncing through my head from Peepo.

For more on literary washing, do read Anita Lahey’s blog post, “Oh, let there be nothing on earth but laundry.” (Lahey had a poem included in the anthology, Washing Lines, a collection of poetry of laundry and washing.) And see also Matilda Magtree (Carin Makuz) with “Pinning, Pining and Penning,” about repairing clothespins and other essential acts.

March 17, 2015

After Birth by Elisa Albert

No, listen, she says, the problem is no one cares about babies. I mean, they care about babies like “oh look at the cute baby” or “oh, ha ha, funny looking baby with an old man voice-over,” but no one actually cares about babies. I mean the details, it’s boring.

So let’s imagine that the ideas this book is concerned with do not matter. Let’s discuss it as a piece of literature, divorced from its subject(s). Elisa Albert’s third novel, After Birth, is an angry, passionate, gnarly and perfect mess of a novel that echoes Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s The Yellow Wallpaper in style and tone (and exclamation marks!), and also Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar, and more recently Claire Messud’s The Woman Upstairs for the force of its rage. Its narrator, Ari, at one point references her favourite Grace Paley story (“Wants”). Which is to say that this is a novel constructed on a strong literary tradition. Its short clipped sentences are notes and dispatches from a place of confusion, attempts to reconcile life itself with one’s expectations of it, and other realities including people’s Facebook profiles and feminist theory. The notes and dispatches do not comprise a plot so much as a circling round of a fact, a record of a winter of inertia. So what moves the book forward then? Well, voice, first—Ari’s is distinct, disturbing, unnerving, frustrating, funny and smart. Second is her vision of the world, which is peculiar and her remarkable articulation of it. And third is curiosity—something’s gotta give. Will she be broken? Will her rage be quashed? And are these two questions actually one and the same? Albert’s first-person address is so solid, so realized, that it gives the impression of having been carved out of something larger, chiseled, rather than built up from the ground. Nothing is incidental or extraneous in her prose. The book and its narrator are exhausting to encounter, frustrating, untameable, and brilliant.

2.

No, listen, though, the problem is with books, with novels about motherhood. Or even worse, those novels that purport to finally pull back the veil and “tell the truth about motherhood.” The problem, in addition to the fact that nobody cares about babies, is that a book about motherhood is rarely read (if it is read at all) as a book about a mother. Instead, it’s a manifesto. Read as a statement on an institution instead of a literary work about a fictional character. A story. We have a hard time grasping that there can be more than one story about motherhood, or if there is more than one, there’s just two then, always diametrically opposed. Two gals facing down on the cover of a magazine. One is always carrying a briefcase. When in reality, there are so many stories, and each of those stories comprise so many stories in themselves, the same way that a single day can hold more than one kind of weather.

“The buildings are amazing in this shitbox town,” is the first line of After Birth, which isn’t nuanced, but it kind of is. And readers and reviewers rarely know what to do with that.

3.

No listen, the problem is that there are the early days of motherhood, and then there is what happens a while after that, when you’ve finally got it figured out, and you feel obligated to go out and deliver everybody else from the darkness. This was the point at which I sent my cousin a completely revised version of her baby registry, when I would start to hyperventilate at the idea of a friend choosing not to co-sleep, when I wanted to chase desperate looking women down who were pushing strollers down the street and put my arms around them, promise them everything was going to be okay. Which was surely the last thing these sorry people needed. And some of them weren’t even sorry. It took me a long time to understand that.

“In the cafe where I never work on my dissertation is the woman I’ve seen at the co-op with her brand-new baby. We smile./ Do you ever feel like you’re completely losing your mind?/ Her smile fades./ It’s okay if you do. It’s perfectly normal.”

4.

No, listen, the problem is women. How we look at other women as mirrors, desperate for affirmation. But it’s always slightly unnerving to look in a mirror, and the reflection is inevitably backwards. Albert’s novel references a 1990s third-wave feminist utopia, Ani DiFranco. Dar Williams singing, “I will not be afraid of women.” But even when we’re not afraid, women are not always good to each other. Like people in general, women are like that. Perhaps more so because of the way in which we’re set up for failure in our engagement, taught to see others as opponents. Ari’s stepmother is an evil feminine archetype, her cousin becomes Bridezilla, and she herself occupied a nasty role as “the other woman” before she married her husband (though she’s not self-aware enough to interrogate this idea. Or is too much so.) She documents her history with female roommates at university, at a private girls high school, at Jewish summer camp, with not one but two moms’ groups. Women are ever disappointing.

Women are ever disappointing for a variety of reasons, both women in the book and women in the world, but part of the problem is that we’re forever looking for that mirror, for affirmation.

“Do you ever feel like you’re completely losing your mind?/ Her smile fades./ It’s okay if you do. It’s perfectly normal.”

“I’m v happy to see women engaging and disagreeing. Most necessary. Interrogation is essential,” wrote my friend Anakana Schofield in a tweet last week, in response to Jessa Crispin on Leslie Jamison’s The Empathy Exams and being tired of female pain (and I’d noted that Jamison was tired of people who were tired of it.)

I think that this is a very good point. We need to know how to look at other women without looking for our own reflection. We need to learn to disagree and not end up shattering glass.

5.

“Two hundred years ago—hell, one hundred years ago—you’d have a child surrounded by other women: your mother, her mother, sisters, cousins, sisters-in-law, mother-in-law. And you’d be a teenager too, too young to have had any kind of life yourself. You’d share childcare with a raft of women. They’d help you, keep you company, show you how.”

No, listen, the problem is we have no rafts of women. With After Birth, as with so many other books about mothers, the problem is not motherhood itself, but instead a motherhood that puts a woman apart from the world, both in practical terms (Ari is removed from familiar surroundings in a new town, isolated while her husband is oblivious and busy with his work) and theoretical ones (remember? No one cares about babies. Ari’s concerns are nobody else’s, her’s alone). Her own mother is dead (and Ari’s memories of her are rife with anger at her mother’s anger—interestingly, it doesn’t seem to occur to her to wonder what her mother was so angry about) and she has no sister. She’s estranged from her Aunt, and her from her heritage (it seems) but marrying a man who isn’t Jewish.

“Here’s the problem: we are taught nothing. / How to sew, grow food, preserve food, build things, fix things, make fires, birth babies, care for babies, feed babies, move through time, grow old, die, grieve, change, sit still, be quiet.”

Here’s another problem though: was there ever really a raft of women?

Two hundred years ago, I thought as I read this, you probably would have died.

Moreover, while Ari craves the idea of this raft of women, she has spent much of her own life setting herself adrift from any semblance of one. She doesn’t wish to be anything like her own mother, or be the same kind of mother. She sees her baby as the chance for a fresh start. She wants a natural birth, to breastfeed, to eschew all things toxic and synthetic—her mothering to be nothing like the way her own generation was mothered. She wants a link that’s wholly illusory.

After Birth is a fascinating companion to Eula Biss’s On Immunity. I couldn’t help but wonder what Ari would have done had she met a woman like Biss in one of her moms’ groups, a woman who in her book thanks the mothers with whom she’d shared the conversations and preoccupations of early motherhood: “These mothers helped me understand how expansive the questions raised by mothering really are… I am writing to and from the women who complicated the matter of immunization for me…In a culture that relishes pitting women against each other in ‘mommy wars,’ I feel compelled to leave some traces on the page of another kind of argument. This is a productive, necessary argument—an argument that does not reduce us, as the diminutive mommy implies, and does not resemble war.”

Albert too demonstrates how expansive the questions raised by mothering really are. This isn’t really a book “about” motherhood at all, but instead, motherhood is its starting point.

Like many of the women in Biss’s book, Ari feels, and indeed has been, failed by the medical establishment. Her unhappiness in motherhood she puts down to the trauma of her c-section. When her friend acknowledges the experience as a kind of rape, Ari feels gratified for just a moment. And perhaps this is the link to her maternal lineage, Ari’s own particular raft of women: her own mother died from cancer caused by drugs her grandmother had taken in pregnancy to avert miscarriage. Those same drugs had left her mother with mutilated reproductive organs so that Ari herself was only conceived and born by remarkable chance. The rape too—her grandmother was raped by Nazi soldiers during the Holocaust. Survived only, Ari tells us, by having sex with them.

Naturally, the idea of witches appeals to her, of women back in history who banded together, who possessed the wisdom of how to deliver babies and cure illness (and even vaccinate, as Biss tells us). She rescues a new friend, Mina, from the throes of early motherhood by nursing her baby, an age-old practice. The two of them set up a raft of their own, and for a time, this is everything.

(I was once so angry at having had a c-section that I was given a pamphlet for a support group that helps women heal from and grieve their c-section experiences. “What kind of bullshit is this?” I was exclaiming and my terrible husband with an evil glint in his eye said, “I think you should go.” I protested and he shrugged calmly: “You’ve been grieving your c-section for four years,” he said. My fist shook at the ceiling. “I am allowed,” I told him, “to grieve my c-section and find c-section support groups totally stupid.” You can see how Ari was someone for whom I had great empathy.)

7.

No, listen, the problem is that no one ever talks about this stuff. Or maybe that when they do talk, nobody listens. See point one: Nobody cares about babies.

“Adrienne Rich had it right. No one gives a crap about motherhood unless they can profit off it. Women are expendable and the work of childbearing, done fully, done consciously, is all-consuming. So who’s going to write about it if everyone doing it is lost forever within it?”

(Or perhaps it’s that even those who are listening have no context. [“Could it be true that one has to experience in order to understand? I have always denied this idea, and yet of motherhood, for me at least, it seems to be the case.”—Rachel Cusk, A Life’s Work].)

Here is something I love about After Birth: Albert doesn’t think that a novel about new motherhood need read like the catalogue for a hipster baby boutique. The stuff is not the stuff, she knows. Stuff is lazy shorthand. It’s a way of getting away from the point.

There is so much I love about how Albert captures the crisis of new motherhood in After Birth. (Her non-fiction piece on this in the Guardian is one of the best things I have ever read about this topic.)

“The baby books said nothing about this. Days became nights became days because nights.” And, “So the dissertation thing is pretty much a lie. But you need an identity, some interest and occupation outside having a kid, you just do. Otherwise the kid will be your sole interest and occupation, and we all know how that works out for everyone.”

And, “I did not understand how there could be no break. No rest. There was just no end to it. It went on and on and on.”

And, “When I see pregnant women, I want to take them by their shoulders and shake. I mean shake. Are you ready?”

And, “I nurse while she pumps to encourage supply. She says something about it being difficult to get out when the weather’s so shitty and I say something like yeah, winter’s a shitty time to have a baby and she says something like it’s always kind of a shitty time to have a baby though isn’t it?”

7.

The problem, sweetheart, is you.

This is a line delivered by the ghost of Ari’s bitch mother near the end of novel when Ari finally confesses, “Fine, I do hate women… They’re so obedient, traitorous. Descendants of the ones who gave up other women as witches.”

Her mother’s line is important because it’s kind of true, in particular as suggested by the novel’s final sentence. The problem is Ari, because she is a specific literary character and not a statement on womankind or motherhood (and many a commenter on Goodreads seems to have difficulty understanding this distinction). She’s a fascinating, messed-up, smart and self-destructive literary character. She doesn’t affirm anything. You will think she is wrong about a lot of things. But this doesn’t mean she’s not worth reading. In some ways, it makes her so much more worth reading than any literary character whose story can be tied up in a perfect bow.

The line is also important as a statement on motherhood though, an idea I’m still teasing out. That while indeed the problem is that women are all too isolated in early motherhood (and they are), it’s not just that other women don’t save us, but that they can’t. That every woman has to discover her own way through. Naomi Stadlen writes about this in a book called What Mothers Do that I found troubling for its simplistic notions and failure to understand maternal ambivalence, but the following passage in one of the smartest I’ve ever encountered on the subject:

“If she feels disoriented, this is not a problem requiring bookshelves of literature to put right. No, it is exactly the right state of mind for the teach-yourself process that lies ahead of her. Every time a woman has a baby she has something to learn, partly from her culture but also from her baby. If she really considered herself an expert, or if her ideas were set, she would find it very hard to adapt to her individual baby. Even after her first baby, she cannot sit back as an expert on all babies. Each child will be a little different and teach her something new. She needs to feel uncertain in order to be flexible. So, although it can feel so alarming, the ‘all-at-sea’ feeling is appropriate. Uncertainty is a good starting point for a mother. Through uncertainty, she can begin to learn.”

8.

And she does learn—this is the thing. Perhaps even Ari will. And not long after the end of the first year (which for me was when storm had ceased, I could see the shapes of things, but trauma was still so recent, and I wrote this) those early days begin to fade. Motherhood itself becomes less all-consuming (literally and figuratively), one’s rage at having a c-section or not becomes less potent, the baby becomes a human, breastfeeding is no longer such a preoccupation, sharing parental duties becomes easier, you sleep more, and it’s all less boring and shattering.

Which is to say that Elisa Albert has documented a very particular moment in motherhood in After Birth, instead of motherhood in general. And that this insistence upon specificity—in spite of her narrator’s generalized wailing in collective pronouns (which is what trips less-careful readers up, I think), in spite of the moments in which our identification with her is visceral—is the novel’s greatest strength. Specificity is what turns a political statement (and oh, this is one) into literature.

March 16, 2015

My review in CNQ 92

I’m very pleased to have a book review in Issue 92 of Canadian Notes & Queries, which should be on newsstands now or soon. I’m pleased first because it’s a neat issue—my friend Rebecca Rosenblum wrote a wonderful essay about the role played by levelled readers in early literacy, and I loved JC Sutcliffe’s piece on Innu and Inuit translation (including of Sanaaq), and lots of other intriguing pieces I have yet to explore in their entirety, including Alex Good’s talked-about take-down on “Canlit’s ruling gerontocracy“.

I’m very pleased to have a book review in Issue 92 of Canadian Notes & Queries, which should be on newsstands now or soon. I’m pleased first because it’s a neat issue—my friend Rebecca Rosenblum wrote a wonderful essay about the role played by levelled readers in early literacy, and I loved JC Sutcliffe’s piece on Innu and Inuit translation (including of Sanaaq), and lots of other intriguing pieces I have yet to explore in their entirety, including Alex Good’s talked-about take-down on “Canlit’s ruling gerontocracy“.

But I am really pleased about my review in the issue because it’s of Mireille Silcoff’s Chez L’arabe, which was a really great book, one of my favourite reads of last year. And because my review is one of the best I’ve ever written, I think. I worked really hard on it and I’m really proud of it as a testament to Silcoff’s work and as a piece of writing in its own rite.

But I am really pleased about my review in the issue because it’s of Mireille Silcoff’s Chez L’arabe, which was a really great book, one of my favourite reads of last year. And because my review is one of the best I’ve ever written, I think. I worked really hard on it and I’m really proud of it as a testament to Silcoff’s work and as a piece of writing in its own rite.

“In Illness as Metaphor, Susan Sontag writes, “the most truthful way of regarding illness… is one purified of…metaphoric thinking.” Albeit from an angle less concerned with truth than fiction, celebrated journalist Mireille Silcoff, in her debut story collection, Chez L’arabe, also situates illness as a point at which metaphor fails. At the centre of the book is a character suffering from a condition in which the spinal cord develops holes and begins leaking fluid until there is “no cushion around [the] brain, soft brain knocking against hard skull, no buffer, and every car ride felt like a prelude to an aneurysm.”

And what is the reader to do with that?

And what is the reader to do with that?

Metaphorically speaking, this affliction is a universal one, particularly in literature. Has there ever been a book that was not about metaphoric bumps in the metaphoric road that makes minds hurt (metaphorically)?

But no, the metaphor is too obvious, too awful. Particularly when we’re presented with a character walking to the car with her tripod cane, who then must lie face down across the backseat with her nose pressed into a cushion. “[P]lease be very careful on the potholes,” she tells her taxi driver. There is nothing metaphoric about that.

Sometimes, as both Silcoff and Sontag show, a thing is just a thing, and thus it is materiality with which Chez L’arabe is preoccupied.”

Buy the magazine, and read the whole thing. And then read the book. Read everything!

March 16, 2015

Best Book of the Library Haul: March Break Edition

Our March Break plans are modest ones: museum, art gallery, library, visits with friends in the morning, and then Iris nap times in the afternoons while Harriet watches movies and I work. Unlike the previous years, Stuart doesn’t have the week off too, and I’m less interested in adventuring without him. Though tomorrow I am taking Iris on the streetcar untethered, with only Harriet for support, moral or otherwise, which might be more adventure than I’m bargaining for. Other good things about March Break are that spring temperatures are here and it’s glorious, and also that it’s the first March Break ever during which I’m not awaiting biopsy results—that was always really poor scheduling on my part.

Our March Break plans are modest ones: museum, art gallery, library, visits with friends in the morning, and then Iris nap times in the afternoons while Harriet watches movies and I work. Unlike the previous years, Stuart doesn’t have the week off too, and I’m less interested in adventuring without him. Though tomorrow I am taking Iris on the streetcar untethered, with only Harriet for support, moral or otherwise, which might be more adventure than I’m bargaining for. Other good things about March Break are that spring temperatures are here and it’s glorious, and also that it’s the first March Break ever during which I’m not awaiting biopsy results—that was always really poor scheduling on my part.

Another good thing is that we got a fantastic library haul last week, which has meant it’s March Break, and the reading is splendid. And the best of the bunch is The Worst Princess by Anna Kemp and Sara Ogilvie. I’ve been championing anti-princess princess books for awhile now, but this one really takes the tiara. It’s in rhyming couplets, first, which is my definition of a picture book to die for. And tea and teacups and teapots recur throughout the narrative, which happens in most of my favourite books, and the children delight in pointing them out.

Another good thing is that we got a fantastic library haul last week, which has meant it’s March Break, and the reading is splendid. And the best of the bunch is The Worst Princess by Anna Kemp and Sara Ogilvie. I’ve been championing anti-princess princess books for awhile now, but this one really takes the tiara. It’s in rhyming couplets, first, which is my definition of a picture book to die for. And tea and teacups and teapots recur throughout the narrative, which happens in most of my favourite books, and the children delight in pointing them out.

The Worst Princess is Sue, whose been waiting around for her life to begin, reading up on all the stories to find out just how one goes about landing a princess. She’s grown her hair to extraordinary lengths, kissed frogs, slept on peas, all for naught. She is lonely and terrifically bored, and then delighted when her prince finally comes. Except that he’s built her a tower and expects her to stay in it locked away from the world—it seems that the prince has read all the books too. But Princess Sue has no truck with that. When not long after, she spies a dragon in the distance, she flags him and down and makes a deal (over a cup of tea, of course). He blows down her tower, sets the prince’s pants on fire, and then Sue and Dragon take off on a series of adventures, “making mischief left and right/ for royal twits and naughty knights.”

The Worst Princess is Sue, whose been waiting around for her life to begin, reading up on all the stories to find out just how one goes about landing a princess. She’s grown her hair to extraordinary lengths, kissed frogs, slept on peas, all for naught. She is lonely and terrifically bored, and then delighted when her prince finally comes. Except that he’s built her a tower and expects her to stay in it locked away from the world—it seems that the prince has read all the books too. But Princess Sue has no truck with that. When not long after, she spies a dragon in the distance, she flags him and down and makes a deal (over a cup of tea, of course). He blows down her tower, sets the prince’s pants on fire, and then Sue and Dragon take off on a series of adventures, “making mischief left and right/ for royal twits and naughty knights.”