March 15, 2015

Higher Ed by Tessa McWatt

There seems to now be a tradition of me beginning reviews of novels by Tessa McWatt—Vital Signs in 2011 and Step Closer in 2009—with a comment upon their strangeness, and now it would just seem wrong if I didn’t. Part of might be their author’s point of view—Guyanese-Canadian-turned-Londoner— which is a rare one in CanLit, and her sentences, with their particular rhythm and cadence, how the prose seems inflected by the beats and thrums of everyday life, how actual people think and speak. And also McWatt’s preoccupations, with theories and ideas instead of the minutia of plot. Her characters, while they talk like actual people, don’t quite move about in the world like actual people. They exist to prove a higher point, which is kind of a criticism, but not really. It’s more to note that to read a Tessa McWatt novel is to read a little differently, and that we’re not reading for realism anymore.

There seems to now be a tradition of me beginning reviews of novels by Tessa McWatt—Vital Signs in 2011 and Step Closer in 2009—with a comment upon their strangeness, and now it would just seem wrong if I didn’t. Part of might be their author’s point of view—Guyanese-Canadian-turned-Londoner— which is a rare one in CanLit, and her sentences, with their particular rhythm and cadence, how the prose seems inflected by the beats and thrums of everyday life, how actual people think and speak. And also McWatt’s preoccupations, with theories and ideas instead of the minutia of plot. Her characters, while they talk like actual people, don’t quite move about in the world like actual people. They exist to prove a higher point, which is kind of a criticism, but not really. It’s more to note that to read a Tessa McWatt novel is to read a little differently, and that we’re not reading for realism anymore.

Which is not to say that McWatt doesn’t engage with reality, particularly here in Higher Ed, her sixth novel. It takes place in London a few years ago on the verge of economic meltdown against the backdrop of a polytechnic-turned-university facing the inevitable funding cuts. Jobs are on the line—film professor Robin knows this doesn’t bode well for him as the most junior in his department and a theorist who doesn’t impart skills that translate into employability; administrator Francine, an American ex-pat, is also expecting to be sacked, as she had been not long ago by her boyfriend, therefore finding herself in her 50s without much of a foundation to stand on; Katrin, a Polish emigre (with a degree in economics), is trying to keep her menial job in a cafe but she keeps being tripped up; and then Ed, who works for the Council making final arrangements for those who have no one else to do it for them. One of the last vestiges of that society that Margaret Thatcher was so determined to prove didn’t—or needn’t—exist.

And then there is Olivia, an idealist, a law student. Biracial, she’s grown up with her white mother and her racist granddad (“He’s the kind of geezer who fools you, who is clever and doesn’t raise his voice except at the telly, talks like he has schooling, talks like he reads books, but deep down Granddad’s ignorance is as deep as his unknowing of his own soul.”). All she’s ever really known about her dad is that he left her, but when she stumbles upon him—he is Ed who works for the Council—while researching a project on paupers’ graves, she learns there is more to her story than she thought. Determined to save her father’s job—because her mother is hardly going to take him back if he’s unemployed, right?—she ropes Robin the film prof into coming up with a plan to celebrate the poetry of Ed’s work, to perhaps highlight the necessity of a job like his in a world that has any hope of being decent.

But Robin is not the right guy for the task, really, and he’s got concerns of his own—he’s fallen in love with Katrin from the cafe just as his ex-girlfriend has told him she is pregnant. Meanwhile, Katrin is calculating how she’s going to have her mother come live with her in London, how she’s going to be able to afford a flat that’s bigger than her bedsit. These people walk the same halls as Francine, who’s been traumatized by witnessing a man killed in a motorcycle accident (whose belongings in the home where he was a lodger will be eventually secured by his family in Italy, thanks to Ed) and is walking on the edge of something that’s going to change her life—for better or for worse.

The diversity of voices in the novel is impressive, McWatt convincingly infusing each character’s narrative with the appropriate vocabulary and syntax based upon the character’s background. Each character’s story comes with its own richness, which is enhanced by the opportunity to see these people from another’s point of view. How exactly their lives overlap seems forced seemed forced times, but these instances were forgivable—these lives were compelling enough no matter their trajectory. But I’m still a bit confused by the effect of all their lives together—what do all these pieces mean? My lapse in understanding partly due to my own failings—if I’d read the work of philosopher Gilles Deleuze, would it all have been clearer? And so I’m as puzzled as I ever was, but confident in McWatt’s project, that—as her character suggests in Step Closer—“There is an order here, awkward and quiet, even now, if you look carefully.” Which you could say about the world—or at least its cities—, I suppose, and McWatt’s achievement is a novel that’s a microcosm of such a thing.

March 12, 2015

Sidewalk Flowers by Jon Arno Lawson and Sydney Smith

It’s from picture books that I’ve learned that the best books have to be read at least 10 times before you really get a handle on them. Case in point: Sidewalk Flowers by JonArno Lawson and Sydney Smith. A wordless picture book (though a wordless book with an author, take note!) can slip past one pretty quickly. The first time I read it, I thought it was okay. A bit weird. The next few times, I still wasn’t sure. It’s the story of a young girl walking through the city with her father, her red-hoodie one of the few spots of colour on the page for much of the book. The other colour comes from the flowers she encounters on her journey, flowers which are actually weeds, which is the kind of distinction only adults make. In their ubiquity, we forget to note how remarkable it is that a dandelion—a living thing—can grow between cracks in the sidewalk. That a wild thing can be so determined to live, and how wildness continually thwarts a city’s attempt to tame.

It’s from picture books that I’ve learned that the best books have to be read at least 10 times before you really get a handle on them. Case in point: Sidewalk Flowers by JonArno Lawson and Sydney Smith. A wordless picture book (though a wordless book with an author, take note!) can slip past one pretty quickly. The first time I read it, I thought it was okay. A bit weird. The next few times, I still wasn’t sure. It’s the story of a young girl walking through the city with her father, her red-hoodie one of the few spots of colour on the page for much of the book. The other colour comes from the flowers she encounters on her journey, flowers which are actually weeds, which is the kind of distinction only adults make. In their ubiquity, we forget to note how remarkable it is that a dandelion—a living thing—can grow between cracks in the sidewalk. That a wild thing can be so determined to live, and how wildness continually thwarts a city’s attempt to tame.

And the flowers grow, and the child finds them, picks them. She’s the only one who notices these bits of wild colour on the urban scene, but they’re not all she’s noticing. (This novel’s grasp of the child’s eye view makes it an interesting companion to the award-winning The Man With the Violin). As her father talks away on his cell-phone, and the people around her conduct their business, she sees other things, other colours—the orange of citrus fruit for sale at a greengrocers, the warm yellow of a taxi-cab, a woman in a floral dress who is reading a book at a bus stop. She’s gathering her wild bouquet, part of which she, calling no attention to herself in the process, offers to a dead bird she walks by on the sidewalk, then to a man who is a asleep on a park bench, and to a neighbour’s dog. And as she leaves her flowers, something remarkable is happening to the world all around her—bit by bit, the city becomes rich with colour. Leaves appear on the trees and the sky turns blue. Through the girl’s small acts, the world is transformed.

And the flowers grow, and the child finds them, picks them. She’s the only one who notices these bits of wild colour on the urban scene, but they’re not all she’s noticing. (This novel’s grasp of the child’s eye view makes it an interesting companion to the award-winning The Man With the Violin). As her father talks away on his cell-phone, and the people around her conduct their business, she sees other things, other colours—the orange of citrus fruit for sale at a greengrocers, the warm yellow of a taxi-cab, a woman in a floral dress who is reading a book at a bus stop. She’s gathering her wild bouquet, part of which she, calling no attention to herself in the process, offers to a dead bird she walks by on the sidewalk, then to a man who is a asleep on a park bench, and to a neighbour’s dog. And as she leaves her flowers, something remarkable is happening to the world all around her—bit by bit, the city becomes rich with colour. Leaves appear on the trees and the sky turns blue. Through the girl’s small acts, the world is transformed.

It all happens so subtly, it takes until around the 10th read that it begins to be clear. And even then, the reader is still uncovering new details in Smith’s illustrations—the lion in Chinatown, a cat in the window, the streetcar coming around the corner (which is red!). The images are made interesting and complicated by shadows and reflections, adding extra texture to the story. Smith is depicting an any-city, though the savvy among us will see Toronto with its distinctive architecture and peculiar topography suggested by houses situated up flights up steps on steep hills.

Sidewalk Flowers is a book with mystery at its core, a book that is a manifestation of its theme of generosity, for it has given me something new every time I have encountered it. A wordless book too is an important tool for literacy, for it allows parent and child to remember the reason we open books at all. For them to approach a story for once on the very same level—a whole world to be explored together.

March 11, 2015

Intolerable: A Memoir of Extremes, by Kamal Al-Solaylee

Kamal Al-Solaylee’s Intolerable: A Memoir of Extremes is the final book of my 2015 Canada Reads selections, and an interesting way to finish them off having started with Thomas King’s The Inconvenient Indian. Both are non-fiction and work to complicate perceptions of people some of us best know from stereotypes. Both also reframe history to present their people—King with Canada’s First Nations and Al-Soylaylee with Muslims in the Middle East—as victims of a capitalism. For Al-Soylaylee, this is only a small part of the narrative, but it’s an important one—he sees the move toward extremism in Egypt being fundamentally linked to Anwar Sadat’s open-market policies and free-market capitalism in the 1970s, which drove Egyptians into poverty and situated the state as an enemy of the people. Politicized Islam filled the gaps. Al-Solaylee states, “And because Egypt exerted huge cultural and moral influence on other Arab countries, the shift towards a more politicized and economics-driven notion of Islam quickly spread to other parts of the region.”

Kamal Al-Solaylee’s Intolerable: A Memoir of Extremes is the final book of my 2015 Canada Reads selections, and an interesting way to finish them off having started with Thomas King’s The Inconvenient Indian. Both are non-fiction and work to complicate perceptions of people some of us best know from stereotypes. Both also reframe history to present their people—King with Canada’s First Nations and Al-Soylaylee with Muslims in the Middle East—as victims of a capitalism. For Al-Soylaylee, this is only a small part of the narrative, but it’s an important one—he sees the move toward extremism in Egypt being fundamentally linked to Anwar Sadat’s open-market policies and free-market capitalism in the 1970s, which drove Egyptians into poverty and situated the state as an enemy of the people. Politicized Islam filled the gaps. Al-Solaylee states, “And because Egypt exerted huge cultural and moral influence on other Arab countries, the shift towards a more politicized and economics-driven notion of Islam quickly spread to other parts of the region.”

How does it connect to the other Canada Reads books? Like Ru, this is the story of an immigrant’s journey to Canada and place to call home, and the narrator’s starry-eyed idealism never wavers. Like When Everything Feels Like the Movies, it’s a story of growing up gay and seeking a place where one can belong—although the characters’ journeys are very different, partly because we don’t have the same access to Al-Solaylee’s isolation that we do Raziel Reid’s Jude’s. Al-Soylayee’s narrative strikes me as similar to the image on the cover—a writer moving from darkness to light but he’s so focussed on that momentum that the dark corners are left unexamined. They’re alluded to—he writes of falling into a years-long depression after a trip to Yemen in the 2000s, years after leaving. But most of the story merely skims the surface on the road from there to here.

Which is not entirely mere—it’s a fascinating road. His own family’s from affluence to poverty; from enlightened liberal ideals to religious extremism; from Yemen to Beirut, to Cairo, and back to Yemen again. It’s a movement that’s emblematic of transformations in the Middle East in general. While Al-Solaylee’s had a different trajectory—to get OUT, whatever it takes. Living as a gay man in Yemen, in his own family, would be impossible. Could be punishable by death. And so he plots his path—to England to study, and then to Canada. By the time he’s made his success in Canada as a journalist and cultural critic, the gulf between his world and his family’s is nearly impossible to bridge. He doesn’t even want to try. He writes of his terror at border crossings still—his fear at being forced back to the world he’s escaped. By the time his mother dies, he’s just about given up on remaining connected with his family. He has spent years turning his back on his Arabness—the language, the culture, the geography. And was this selfishness or self-preservation? He’s not entirely sure of this. But then with the 2011 Arab Spring and war and unrest in Yemen, Al-Solaylee finally realizes that he can’t entirely disown the places—and the people—he comes from. And it’s this transformation that to me is the most compelling journey in the book.

Intolerable is the link between the three Canada Reads books I’ve already noted, and the fourth, Jocelyn Saucier’s And the Birds Rained Down. Because it’s also a book that’s all about choice, except that it’s mostly about what happens to people who don’t have any. Al-Soylaylee notes that he took the freedom to pursue his dreams in Canada, while his sisters—educated and once-liberated women—retreated to Islam. They tell him they find comfort there, but he’s not sure they would have been permitted comfort anywhere else. And even his brothers, whose hard-line points of view were pivotal to eventually wearing down their sisters’ resistance to religious infringement upon their lifestyle, are given a bit of leeway. What else did these men have? It’s true, Al-Soylaylee notes, that his brother became more devout the worse he did at school, but even if he had been successful, what opportunities could a country like Yemen have offered him? Over and over again we see that poverty and economic stagnation is a hole that radical Islam rushes to fill.

While not as structurally innovative as the other Canada Reads books, there is a whole lot going on here, but, as I’ve said, it’s happening far beneath the surface. I found the prose confusing at times, sentence after sentence beginning with conjunctions to show disagreement—even, but, although, however, though. To the point where Al-Solaylee is not debating between sides but moving in circles, suggesting his own discomfort with his history, with his take on it, and that he’s still not sure how to hold it. While this detracts from the subject matter a bit, keeping the writing from going as deep as I’d like, it’s also interesting to consider, and typical of something that promises “a memoir of extremes”. That while where we’re talking about breaking barriers, life is complicated, not necessarily two-sided simple, and that some barriers are not easily broken.

March 10, 2015

An Artist Lives Here

As you know, I love Carson Ellis’s new picture book, Home, and one of its chief delights is the final image, “An artist lives here.” It’s a glimpse into the book’s creation, and a fascinating self-portrait.

It reminded me of another book that we’ve been enjoying, Any Questions by Marie-Louise Gay.

But where is the artist who lives here? Here she is!

And surely, I thought, there must be other examples? It all seemed quite familiar, vivid in my mind’s eye. But when I thought about it, I came up with nothing. Except for Virginia Lee Burton’s Life Story, which isn’t of an artist in her studio (because her studio, as the book tells us, is in the barn behind the house). But there she is down in the lefthand corner painting a picture of the entire scene, finding inspiration in her own surroundings just like Carson Ellis and Marie-Louise Gay.

There must be more though. What other picture books can you think of in which the artist includes an image of the artist herself at home (which is to say, at work)?

March 9, 2015

On Immunity by Eula Biss

I will admit it: until recently, I was one of those parents whose children weren’t vaccinated due to my concerns about a number of toxic ingredients found in vaccines. But then when people started sharing vitriolic and expletive-filled Facebook statuses and tweets about “fucking anti-vaxxers” whose children deserved to die of smallpox, they really convinced me, and I finally came around and saw the error of my ways.

I will admit it: until recently, I was one of those parents whose children weren’t vaccinated due to my concerns about a number of toxic ingredients found in vaccines. But then when people started sharing vitriolic and expletive-filled Facebook statuses and tweets about “fucking anti-vaxxers” whose children deserved to die of smallpox, they really convinced me, and I finally came around and saw the error of my ways.

Okay, none of the above is true. First, because my children received their vaccines on schedule. But mostly because the described scenario doesn’t exist—no one’s going to change her mind in this climate. The rhetoric surrounding the vaccine “debate” is so inflamed and divisive that as it stands that there is no hope of reconciliation. I also have some sympathy for parents who doubt the safety or necessity of vaccines. While I have absolute trust in my doctor and her advice, and in the importance of vaccines for public health, I was one of the many people who put down that fear-mongering story in The Toronto Star last month on the HPV vaccine and said, “My kids are never going to get that.” And then the whole furor blew up, and I saw how we’d been played.

Which is the point at which I decided to read On Immunity by Eula Biss. Biss, poet and award-winning essayist, wades into the vaccine issue, not to seek a middle-ground—because she acknowledges that there isn’t one; the science is conclusive; her own child is vaccinated—but to seek context, to create something richer than a polemic. More than a book on “issues”, even, this is a book on language and metaphor, about how both frame the way we understand our bodies and our world, and about vaccinations and immunity might serve as a metaphor for America and the world today. “And it has vampires in it,” so notes the blurb on the back by Rebecca Solnit. Because, yes, this book is blurbed by Rebecca Solnit AND Anne Fadiman, which makes it basically a non-fiction holy book. And it is oh so very good.

Biss begins with the myths and fairytales, those stories in which “parents…have a maddening habit of getting tricked into making bad gambles with their children’s lives.” Including the myth of Achilles whose mother seeks his immortality. Biss writes, “Immunity is a myth, these stories suggest, and no mortal can ever be made invulnerable,” and considers the desperate ways in which parents seek to protect their children from their fates.

Her son was born as H1N1 panic spread across the world, around the same time my elder daughter was. I remember lining up for hours at Metro Hall downtown for the flu vaccines we were eligible for because we resided with a member of the vulnerable segment of the population. “It was not a good season for trust,” Biss writes, as financial markets were crumbling and many people were considering the response to the H1N1 panic to be overblown, a plot by big-pharma, the vaccine’s components considering dubious by many in the chattering-mother set.

Biss invokes Bram Stroker’s Dracula, a story that serves as a metaphor for disease. “What makes Dracula particularly terrifying, and what takes the plot of the story so long to resolve, is that he is a monster whose monstrosity is contagious.” And the story, she continues, is as much about the problem of evidence and truth as it is about vampires. How do we ever know what we know?

Public health, Biss notes, is rarely seen by members of the middle class as intended for “people like us.” She uses the example of prominent anti-vaccine campaigner Dr. Bob Sears who writes of the hep B vaccines, “This is an important vaccine from a public health standpoint, but it’s not as critical from an individual point of view.” Biss explains, “In order for this to make sense, one must believe that individuals are not part of the public.” But such a limited perspective is hardly novel, Biss shows shows, with historical epidemics thought to be the scourge of foreigners and outsiders (like Dracula!), and poor black people forced at gunpoint to be vaccinated in Kentucky a century ago. Historically, vaccination of those living in poverty would have benefited the wealthy, whereas the tables have now turned—the vaccination of children who live in privilege now serves to protect the vulnerable (in terms of income level and health). Biss extends her examination of this switch: “If it was meaningful for the poor [historically] to assert were not purely dangerous, I suspect it might be just as meaningful now for the rest of us to accept that we are not purely vulnerable. The middle class may be ‘threatened’, but we are still, just by virtue of having bodies, dangerous.”

But we feel threatened, we do. Here, Biss returns to poor season for trust, and explains how risk perception has more to do with fear than quantifiable risk. “Perhaps what matters,” Biss quotes the scholar Cass Sunstein has saying, “is not whether people are right on the facts but whether they are frightened.” And we certainly live in a culture of fear, which is ever heightened. Which has recently manifested in a paranoia against chemicals, countered with a strange faith that nature itself is benevolent. But vaccines, note Biss, reside where between the two: “vaccines are of that liminal place between humans and nature—a mowed field.” She further complicates the issue by using the example of the Americas’ native populations, decimated by disease after the arrival of Europeans: “Considering this course of events ‘natural’ favours the perspective of the people who subsequently colonized the land, but it fails to satisfy the ‘not made or caused by humankind’ definition of the term.”

Nothing is straightforward, and science writing, and misperceptions of science writing, skews things. Did you know that there is no causal link between DDT and cancers? I didn’t. I read Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, her book that sparked a revolution by suggesting there is no boundary between the human body and its environment, and while this is indeed the case, and while spraying DDT from airplanes over towns and vast tracts of farmland is indeed dangerous and does irreparable damage to ecosystems, Silent Spring‘s greatest legacy, as noted by journalist Tina Rosenberg, is that it’s “killing African children because of its persistence in the public mind.” Malaria has resurged in countries where DDT is no longer used against mosquitos. While Carson recognized the utility of DDT for disease prevention, Biss writes, “the enduring power of her book owes less to its nuances than its capacity to induce horror…. Like the plot of Dracula, the drama of Silent Spring depends on emblematic oppositions.”

Biss traces the origins of vaccines to folk medicine, practiced by women until they were pushed out of their positions of power in their communities by the medical establishment (men who pushed women into unsanitary hospitals to have their babies, many of whom would die there because these doctors didn’t know to wash their hands). Biss notes the strange relationship between anti-vaccine mothers and vaccination itself, both born out of the same anti-establishment systems that seek/sought to undermine women and their intuitive knowledge vs. scientific fact. This is certainly not a story about emblematic oppositions after all. But still, not a reason to turn away from science altogether. We need science, notes Biss, via Donna Harraway. “Where it is not built on social domination, science can be liberating.”

My very favourite part of this book, whose every bit I appreciated so much, was the end-note to page 8 (and it’s a testament to the goodness of On Immunity that I read its notes in entirety. I didn’t want the book to end). Biss writes something that reads like an echo of my introduction to The M Word, about motherhood being one’s occupation and preoccupation in the early days, about all those conversations about motherhood between new mothers making sense of their world, which is also the world. And this is what I find so exciting about this book, that such a work of literature can be from those “productive and necessary” conversations.

Biss notes:

“These mothers helped me understand how expansive the questions raised by mothering really are… I am writing to and from the women who complicated the matter of immunization for me…In a culture that relishes pitting women against each other in ‘mommy wars,’ I feel compelled to leave some traces on the page of another kind of argument. This is a productive, necessary argument—an argument that does not reduce us, as the diminutive mommy implies, and does not resemble war.”

March 5, 2015

Perhaps the alphabetizing is a diversion

There is something. I am not sure what it is. Perhaps we’re that much closer to the sun and the days are longer, though winter is still very present, and maybe it’s that I’m keeping my head down and just trying to make it to the finish line. With March Break on the horizon (and we’re having a Dreaming of Summer party, inviting friends over so their moms can drink sangria in the morning with me), plus we’re spending much of April in England, which I’m so excited about. Before we leave, I am quite adamant that I shall finish the second draft of my novel, so that’s a preoccupation of late. I’ve been reading so many exceptional books (Eula Biss’ On Immunity at the moment), and reading fewer think-pieces. The other day, I culled my to-be-read shelf and got rid all the books I kind of always knew I was never going to read, and all the books that I was intending to read because I thought I should (and while I’ve meant to stop acquiring such books, I sometimes even fool myself). And then I alphabetized the books that were left, whereas before they’d been a series of teetering stacks. And it feels good, tidy, exciting. Though perhaps the alphabetizing is just a diversion. Is it possible that alphabetizing is always a diversion? I don’t think so though. It’s an order to chaos, something that makes sense. Regardless, it does feel like I’m walking along on the edge of something.

There is something. I am not sure what it is. Perhaps we’re that much closer to the sun and the days are longer, though winter is still very present, and maybe it’s that I’m keeping my head down and just trying to make it to the finish line. With March Break on the horizon (and we’re having a Dreaming of Summer party, inviting friends over so their moms can drink sangria in the morning with me), plus we’re spending much of April in England, which I’m so excited about. Before we leave, I am quite adamant that I shall finish the second draft of my novel, so that’s a preoccupation of late. I’ve been reading so many exceptional books (Eula Biss’ On Immunity at the moment), and reading fewer think-pieces. The other day, I culled my to-be-read shelf and got rid all the books I kind of always knew I was never going to read, and all the books that I was intending to read because I thought I should (and while I’ve meant to stop acquiring such books, I sometimes even fool myself). And then I alphabetized the books that were left, whereas before they’d been a series of teetering stacks. And it feels good, tidy, exciting. Though perhaps the alphabetizing is just a diversion. Is it possible that alphabetizing is always a diversion? I don’t think so though. It’s an order to chaos, something that makes sense. Regardless, it does feel like I’m walking along on the edge of something.

What else? Heidi Reimer’s winning essay about female friendship has been published in Chatelaine. I interviewed Marilyn Churley about reuniting with her son and her fight to reform adoption disclosure in Ontario. My profile of Julie Morstad is now online at Quill and Quire. A few weeks back at 49thShelf.com, we did a virtual round-table on The State of the Canadian Short Story that was amazing. And finally, here is a photograph of my children, because I know there are a more than a few readers who visit this site for only that.

What else? Heidi Reimer’s winning essay about female friendship has been published in Chatelaine. I interviewed Marilyn Churley about reuniting with her son and her fight to reform adoption disclosure in Ontario. My profile of Julie Morstad is now online at Quill and Quire. A few weeks back at 49thShelf.com, we did a virtual round-table on The State of the Canadian Short Story that was amazing. And finally, here is a photograph of my children, because I know there are a more than a few readers who visit this site for only that.

March 2, 2015

Great Books Take Non-Fiction Prizes

‘But it is obvious that the values of women differ very often from the values which have been made by the other sex; naturally this is so. Yet is it the masculine values that prevail. Speaking crudely, football and sport are “important”; the worship of fashion, the buying of clothes “trivial.” And these values are inevitably transferred from life to fiction. This is an important book, the critic assumes, because it deals with war. This is an insignificant book because it deals with the feelings of women in a drawing-room.’ –Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own

‘But it is obvious that the values of women differ very often from the values which have been made by the other sex; naturally this is so. Yet is it the masculine values that prevail. Speaking crudely, football and sport are “important”; the worship of fashion, the buying of clothes “trivial.” And these values are inevitably transferred from life to fiction. This is an important book, the critic assumes, because it deals with war. This is an insignificant book because it deals with the feelings of women in a drawing-room.’ –Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own

Non-fiction by women gets the short shrift, even though women are often writing stories that nobody has ever told before, while, does anybody really need about book on WW1? So I am especially happy at the awarding of two recent fiction prizes to excellent books which were among my favourite books of 2014.

Karyn L. Freedman’s One Hour in Paris: A True Story of Rape and Recovery has won the BC National Award for Canadian Non-fiction, and Plum Johnson’s They Left Us Everything today became the first book by a woman to win the Charles Taylor Prize for Non-Fiction since Isabel Huggan won it in 2004. Both these books prove that personal memoirs can indeed have far-reaching global and historical implications, and demonstrate remarkable research, story-telling and insight. They’re exquisite books, and I’m so glad that even more readers are now going to discover this for themselves.

March 1, 2015

The Girl on the Train by Paula Hawkins

Here is a secret: sometimes when we say that a protagonist is unlikeable, what we really mean is that she is boring, or at least her plot is, or that as a character the protagonist fails to get up off the page, live in more than two dimensions. Which is to say that the whole “unlikeable protagonist” thing is not quite the problem that we might think it to be. It’s a shorthand for, I couldn’t be compelled to care about this person. Which is sometimes the fault of the reader, sometimes the fault of the writer. Not every book is for everyone.

Here is a secret: sometimes when we say that a protagonist is unlikeable, what we really mean is that she is boring, or at least her plot is, or that as a character the protagonist fails to get up off the page, live in more than two dimensions. Which is to say that the whole “unlikeable protagonist” thing is not quite the problem that we might think it to be. It’s a shorthand for, I couldn’t be compelled to care about this person. Which is sometimes the fault of the reader, sometimes the fault of the writer. Not every book is for everyone.

Though it seems that The Girl on the Train, by Paula Hawkins, is for an awful lot of people. Bestseller, huge hit, the latest novel to be christened “The Next Gone Girl,” which is something. I read it this weekend, and I loved it, which pleases me the way I like that I can still love hot-dogs, even though I’ve come to frequent the organic butchers. That I can still appreciate this novel, while I see plenty that’s wrong with it—some sloppy prose, a narrative structure that makes no sense, a plot that hinges on a character having a blackout. It’s no Gone Girl, which was a really solid book. But it’s just as gripping, and one thing it does better is that its unlikable protagonist is sympathetic. Gillian Flynn’s Amy was a monster, but while Paula Hawkins’ Rachel is a mess and heading fast down the stupid spiral, she’s incredibly human. We can see how she got to where she is. And its in her humanness (too much so) and not her unlikeability (because she’s that too) that being in her literary presence can be totally unbearable. But the reader persists because there’s a story here that begs to be unravelled.

Rachel travels to and from London every day from her home in the suburbs, the train stopping for a moment by a row of houses into whose back gardens she has a perfect view. She’s become fixated on one particular couple whom she sees drinking wine on their terrace, having breakfast in their kitchen, and she dreams up a whole life for them—her obsession with these people not unrelated to the fact that she’s desperately lonely and that their house is just doors away from the home she’d shared with her ex-husband until he’d dumped her for another woman with whom he now shares the house along with their baby daughter. Rachel’s marriage had broken down on account her drinking, and since her divorce, her drinking problem has escalated, plus she’s lost her job and is about to be thrown out by her flatmate.

Which means she’s not considered the most reliable witness when the woman in her fantasy couple goes missing. Rachel had spied the missing woman with another man the day before she disappears, and she feels this information must be relevant to the case. But there’s also the fact of her increasing attraction to the missing woman’s husband, plus her own ex-husband and his wife who are fast growing tired of her lurking presence outside their door.

While The Girl on the Train is worthy of the hype, in terms of being a fun read, I’d offer that Harriet Lane’s novel Her is a so much better example of the “domestic sinister” genre and more deserving of such hype. And that Lane’s novel, as well as the best parts of Hawkins’, made me think about Emily Perkins’ 2008 Novel About My Wife, which I’ve read twice and want to visit again. Wild women with mysterious pasts (where trauma lurks), disinterested husbands, suburban ennui, the perils of real estate, violence and danger. The likability of a protagonist doesn’t even register. It just matters that you care what happens next.

February 27, 2015

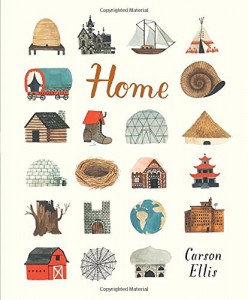

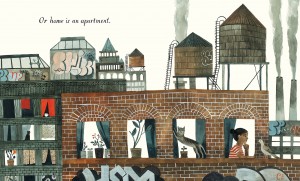

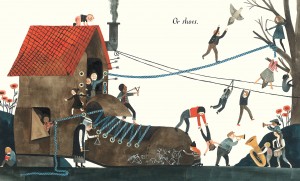

Home by Carson Ellis

While Carson Ellis’ Home is a beautiful book, it first appealed to me conceptually for its similarity to one of my favourite picture books, A House is a House for Me by Mary-Ann Hoberman and Betty Fraser, published in 1978. Both books—with whimsy, strange and gorgeous illustrations (plus a Duchess)—explore the variousness of dwellings, and the curiousness too; from the Hoberman book, “A box is a house for a teabag. A teapot’s a house for some tea. If you pour me a cup and I drink it all up, Then the teahouse will turn into me.” All this to the point where I opened by Ellis’ book, and wondered where were the rhyming couplets.

While Carson Ellis’ Home is a beautiful book, it first appealed to me conceptually for its similarity to one of my favourite picture books, A House is a House for Me by Mary-Ann Hoberman and Betty Fraser, published in 1978. Both books—with whimsy, strange and gorgeous illustrations (plus a Duchess)—explore the variousness of dwellings, and the curiousness too; from the Hoberman book, “A box is a house for a teabag. A teapot’s a house for some tea. If you pour me a cup and I drink it all up, Then the teahouse will turn into me.” All this to the point where I opened by Ellis’ book, and wondered where were the rhyming couplets.

But Ellis’ project with Home is something that’s different, more art-focused than text-focused, and the text itself seeking to open up the book rather than nailing it down, asking questions like, “But whose home is this?” of a home on the edge of a cliff, “And what about this?” of a tiny home underneath a mushroom—a vaguely Alice-ish reference (which gives this book another point in common with Hoberman’s, in addition to a thing for teacups).

So I sat down with my children and we started to look at the book, delighting in the illustrations (which will appeal to anyone who likes Jon Klassen’s work, which is everyone), and the oddities. Sure, homes are boats and wigwams, but what IS going on in that underground lair, and how strange to have “French homes” on a page with the inhabitants of Atlantis (whose homes are, naturally, underwater).

So I sat down with my children and we started to look at the book, delighting in the illustrations (which will appeal to anyone who likes Jon Klassen’s work, which is everyone), and the oddities. Sure, homes are boats and wigwams, but what IS going on in that underground lair, and how strange to have “French homes” on a page with the inhabitants of Atlantis (whose homes are, naturally, underwater).

Homes on the moon, in a geodesic dome in space, the home of a Norse god, a castle in a fish bowl (with the knights riding sea-horses), “A babushka lives here,” “A raccoon lives here.” The strange juxtaposition of the bizarre and familiar—it’s a weird and wonderful book that invites even more questions than those the text poses.

But then we started noticing other things—there is a pigeon on every page, and the same teacup recurs every little while, and there’s a monkey on the ship, and on the shoe-home page, there is a little boy on the roof who’s pulled down his pants, and he’s showing us him bum, and the children were howling. We still couldn’t find the pigeon on the “Bee homes” (though it dawns on me that it’s a wasp’s nest, but I digress) page, so we called in back-up and read the whole book for perhaps the fifth time, in the presence of Daddy. The book was so wholly engaging for the entire family, and we all of us loved it at once.

But then we started noticing other things—there is a pigeon on every page, and the same teacup recurs every little while, and there’s a monkey on the ship, and on the shoe-home page, there is a little boy on the roof who’s pulled down his pants, and he’s showing us him bum, and the children were howling. We still couldn’t find the pigeon on the “Bee homes” (though it dawns on me that it’s a wasp’s nest, but I digress) page, so we called in back-up and read the whole book for perhaps the fifth time, in the presence of Daddy. The book was so wholly engaging for the entire family, and we all of us loved it at once.

“An artist lives here.” is the book’s second-to-final image, showing a person at work in her studio, a room filled with fascinating and ordinary objects all of which (or nearly all of which?) are found within the other pages in the book—a shoe on the floor (sans bum), the fish bowl, stripy socks. And also sketches of the actual illustrations tacked up to the wall, giving the story a new puzzle along with a metafictional subtext, as well as underlining the message that creative inspiration—even for imaginative journeys to the farthest reaches of the universe—can be found in the ordinary world all around us. Which is certainly a testament to the nature of home, indeed.

February 25, 2015

The M Word reviewed in Literary Mama

The M Word was reviewed by Monica Frantz in the latest issue of Literary Mama:

The M Word was reviewed by Monica Frantz in the latest issue of Literary Mama:

“The M Word was an encouragement to me as I celebrated the first anniversary of becoming a mother. I was catching my breath after falling in love and falling pregnant in the span of six months, moving to the suburbs of Washington, D.C., from Manhattan, and surviving one year as a stay-at-home mom with an Ivy League master’s degree. My baby girl was one year old, and my world had shrunk and expanded many times over since that Sunday morning 20 months prior when I saw two lines on the pregnancy test and my boyfriend went out for bagels and decaf coffee to celebrate.

I was beaming at her first birthday party—proud of my girl and myself and thankful for everything our family had—but I also knew that I had lost a lot when I became a mother and that I had gained a new set of fears and anxieties. Reading The M Word gave me—sleep-deprived and desperate for adult conversation—the prompting and inspiration to do some reflecting on what motherhood meant to me. The text was engaging and, in some ways, challenging to my own tendency to seek safety among like-minded mothers.

As I finished reading it, a close friend found out that she was pregnant for the first time. As we celebrated her pregnancy, I hesitated to pass the collection along to her. Superstitious and hoping to protect her, I worried about giving her essays on loss and trauma and regret. But women deserve to hear a conversation about motherhood that is as beautiful and scary and messy and complex as motherhood itself. When her experience of motherhood strays from the accepted stereotype, if it hasn’t already, she’ll know that she is not alone.”