April 9, 2015

Mix CD for the Road

We made a mix CD for our car journey. It was strange having to explain to someone what a mix-CD was. I didn’t even complicate matters by mentioning cassettes (and how you could tape over cassettes by putting masking tape over the tabs on the top edge—remember that?). We are pretty happy with how the track list turned out. We also have a giant ziplock full of candy, so we’re basically all set for days and days of travel. Wish me luck. Don’t remind me not to lose my passport this time though, or I will probably stop liking you.

“Mary Ann and One Eyed Dan“, by Shovels and Rope

“I Really Like You“, by Carly Rae Jepsen

“Sailing“, by The Strumbellas

“Dirty Paws“, by Of Monsters and Men

“Riding in My Car”, by Elizabeth Mitchell and You Are My Flower

“Chandelier”, by Sia

“Let It Go”, by Frozen

“Can You Get To That?”, by Mavis Staples

“Moonquake Lake”, by Sia (Annie Soundtrack)

“Alphabet Dub”, by Elizabeth Mitchell and You Are My Flower

“Happy”, by Jennifer Gasoi

“Twisting the Night Away”, by Sam Cooke

“Love is An Open Door”, by Frozen

See you on the other side! Of the ocean, that is.

April 9, 2015

Motherhood Milestones

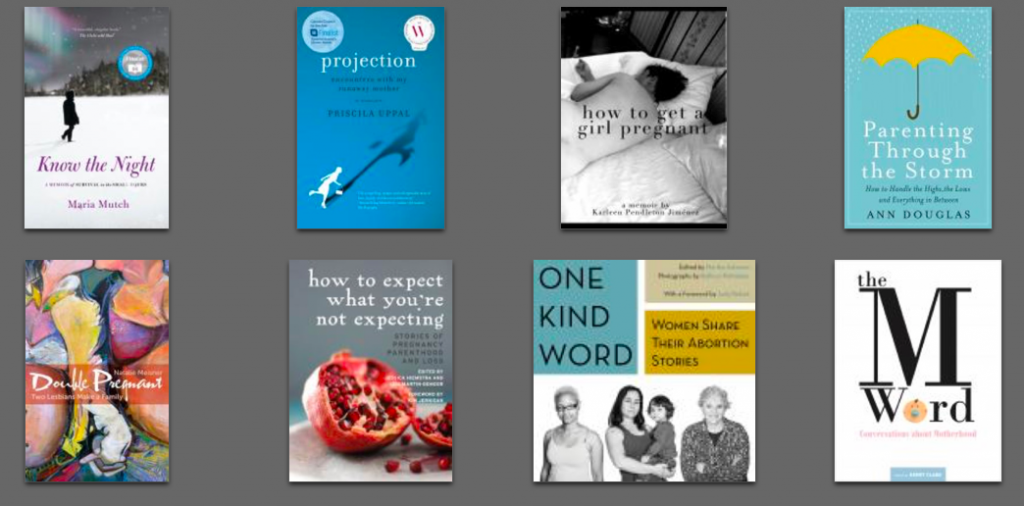

The M Word was published nearly a year ago, and Mother’s Day is just about a month away. To mark both these milestones, I’ve made a list of Canadian non-fiction books that have been expanding the conversation about motherhood along with The M Word.

April 8, 2015

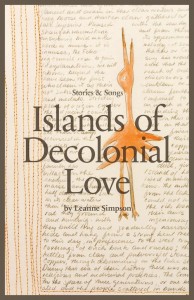

Giveaway: Islands of Decolonial Love by Leanne Simpson

A fouling up on the part of the postal system means that I’ve ended with two copies of Leanne Simpson’s Islands of Decolonial Love, and their mistake might be your good fortune.

A fouling up on the part of the postal system means that I’ve ended with two copies of Leanne Simpson’s Islands of Decolonial Love, and their mistake might be your good fortune.

From my blog post on the book:

“I can’t hold Leanne Simpson’s Islands of Decolonial Love in my hand and tell you what it is. I don’t want to, actually. To say I’m finished with it, that I get it, that it’s just one thing. When these are “Stories and Songs,” and tricky and various. Full of voices—I don’t know that I’ve ever read a collection packed with such a motley crew, every one with a story to tell and power behind it (even when lack of power is the story), blending European and Indigenous literary traditions. I read it last week, and then tonight sat down and listened to the spoken word recordings of some of the pieces, set to music. They’re beautiful, vivid, and you can listen to them here.

Last week, we had a virtual round table on The State of the Canadian Short Story at 49thShelf, in which Doretta Lau had mentioned Simpson’s collection as one that had blown her away. I’d already ordered the book, because Marita Dachsel had mentioned she’d heard Simpson read from it, and it was already included on this list of books by First Nations women (as suggested by Sarah Hunt, who inspired the list). If it hadn’t been on my radar already, Thomas King named Simpson as recipient of the RBC Taylor Prize for Emerging Writers last year.”

Leave a comment below for a chance to win my spare copy of the book in a random draw. Contest deadline is Friday April 18th. Thanks to Arbeiter Ring Publishing and Canada Post for making the magic happen.

April 8, 2015

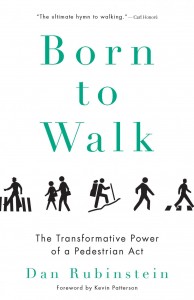

Born to Walk by Dan Rubinstein

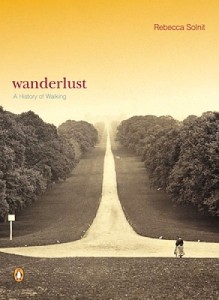

I thought I’d already read the book on walking. Rebecca Solnit’s Wanderlust: A History of Walking is one of the most fascinating books I’ve ever read, a book that opened my eyes to the wonders of rambling and tramping, and to how amazing is the ordinary world around us all the time. How extraordinary is the act of a single step, let alone one after another.

I thought I’d already read the book on walking. Rebecca Solnit’s Wanderlust: A History of Walking is one of the most fascinating books I’ve ever read, a book that opened my eyes to the wonders of rambling and tramping, and to how amazing is the ordinary world around us all the time. How extraordinary is the act of a single step, let alone one after another.

However extraordinary though, we are talking about walking. After Wanderlust, what else needs to be said? So I wasn’t entirely sold on Dan Rubinstein’s Born to Walk: The Transformative Power of a Pedestrian Act—not at least until I opened the book. I saw that Rebecca Solnit was his epigraph (“Perhaps walking is best imagined as an ‘indicator species’ to use an ecologist’s term…”). And realized that the journey, delightfully, continues on.

Whereas Solnit’s book was a history of walking, Rubinstein spreads his net wide and attempts to capture walking right now. What does it mean? How is walking changing lives and places? The book is divided into eight sections—Body, Mind, Society, Economy, Politics, Creativity, Spirit and Family—each one inspired by a central walking narrative with plenty of room for diversions. Rubsinstein, an award-winning journalist, blends memoir, sociology, psychology, cultural commentary and reporting to show how walking connects us to our fundamental selves and also to the natural world.

In “Body”, he journeys with a team led by Dr. Stanley Vollant, an Innu surgeon whose days-long hikes through the remote wilderness reconnects First Nations people with the lives their ancestors led before communities in Northern Canada became settled, hikes that are tests of physical and spiritual strength. (Aside: a quietly groundbreaking study published in 1953 asserting that “regular physical exercise could be one of the ‘ways of life’ that promote health.” More asides: modern labs which study how and why people fall, attempting to create safer stairs—”In Canada, the social and health-care cost of accidents on stairs alone is estimated at $8.8 billion a year.” An exoskeleton that enables paralyzed people to walk. So many asides: this is a text rich and enlivened by desire lines…)

In “Mind,” Rubinstein considers “The Glasgow Effect”—Glasgow has the lowest life expectancy in Western Europe, increased circumstances of psychiatric disorders—and examines programs to counter this effect including neighbourhood walks and connecting people with natural places. This chapter also uses examples of war veterans with PTSD, and the effect of hikes upon their wellbeing. In “Society,” Rubinstein travels the streets of Philadelphia with Police Officers on foot patrol, invokes Jane Jacobs, and demonstrates how different one’s experience of a city is when lived through a car window, or as part of the sidewalk ballet.

My adoration for Born to Walk was cemented with the chapter on “Economy,” which begins with a Canada Post letter carrier making her rounds in Ottawa. What do these kind of individuals offer Jacobs’ sidewalk ballet? And are people who walk for a living happier and healthier than the rest of us? Canada Post is phasing out home delivery, although they made a profit last year and their parcel delivery service is robust due to online retailers such as Amazon. Amazon, not yet fully automated—pickers at their warehouses walk 7 to 15 miles a day, Rubinstein tells us, shifting then to ask what a lack of walking costs us economically, what might be gained by created walking and cycling infrastructure. And what about the possibilities of walking and business? He addresses the walk-around management style, and the idea of walking-meetings. He also interviews two owners of a small dog-walking business. “It pays well and it’s only a half day, so I can also work on other things that I’m interested in… And yeah, the walking. That’s probably the best part.”

My adoration for Born to Walk was cemented with the chapter on “Economy,” which begins with a Canada Post letter carrier making her rounds in Ottawa. What do these kind of individuals offer Jacobs’ sidewalk ballet? And are people who walk for a living happier and healthier than the rest of us? Canada Post is phasing out home delivery, although they made a profit last year and their parcel delivery service is robust due to online retailers such as Amazon. Amazon, not yet fully automated—pickers at their warehouses walk 7 to 15 miles a day, Rubinstein tells us, shifting then to ask what a lack of walking costs us economically, what might be gained by created walking and cycling infrastructure. And what about the possibilities of walking and business? He addresses the walk-around management style, and the idea of walking-meetings. He also interviews two owners of a small dog-walking business. “It pays well and it’s only a half day, so I can also work on other things that I’m interested in… And yeah, the walking. That’s probably the best part.”

In “Politics,” Rubinstein walks with Rory Stewart, a British MP who got to know his constituents by hiking around Northwestern England, going door to door, the same way he’d got to know Afghanistan in 2002, after leaving behind his job in the Foreign Service. (His journeys through Afghanistan culminated in his book, The Places in Between.) The chapter invokes Thoreau, Gandhi, marches on Washington for woman’s suffrage and for civil rights, and First Nations walks in protest in Canada.

In “Creativity,” he takes part in walking as performance art in Brooklyn, considers artists for whom walking as served as muse or medium, and learns about the role of walking in creative cognition. In “Spirit,” he partakes in a hike through Wales, and writes about famous pilgrimages including El Camino in Spain, the Hajj in Mecca and the Kumbh Mela in northern India. He writes about what it means to finish a pilgrimage…and what it means to quit. And the final chapter is “Family,” in which he writes about walking to school with his children—particularly after they were mowed down by an SUV (and it’s always an SUV, isn’t it?) at their local crosswalk. What can we do to make streets safer for children to walk to school, for everyone to walk safely? He cites surprising benefits to walking to school—not just time for conversation and physical fitness, but studies showing that children who walk to school are more deeply connected to their communities geographically and psychologically. And he writes about walking with his children, hikes through nature—how this has always been part of their experience as a family. What it gives them: time, the moment, right now.

And that’s the thing about walking—these vast ramifications, but it often comes down to a little hand in yours, always ordinary until it comes to a tiny person’s miraculous first step.

In our family, we don’t have a car, and so the decision to walk to school isn’t one we ever have to think about. A few times a year, they have a “Walk to School Day” at the school, and we think this is funny, the same way I thought it was funny when someone declared 2014 the year to read women writers. Last year when I wrote about the Rebecca Solnit book (and its companion—the picture book The Silver Button by Bob Graham), Harriet was only 4 and finding the walk to school a bit of a struggle, whereas her legs are longer now and she’s used to it—particularly when she’s unencumbered by snow pants, the walk is not a slog at all. “I was born to walk,” she told me this morning, because she is impressionable, and can read book jackets now, and I’ve been talking a lot about this one. It’s a book whose connections to the world are so multitudinous that you keep putting it down as you’re reading to share something fascinating, and then when the book is done, you go out walking down the street, and the connections all come back to the other way.

Iris, who is not quite 2, is a different creature than her sister was, bipedally speaking. She wants to walk everywhere, shouting “Walkie! Walkie!” if we dare constrain her in her stroller, and she doesn’t just want to walk—she does walk. Last Tuesday, she walked down Bloor Street from Spadina to Bay. It’s her favourite thing in the world—she seems to know everything in Rubinstein’s book innately—to be motoring on her own steam, and so completely free.

April 6, 2015

Departures and Arrivals

We leave for our trip this week, and I keep waiting for that lull between our departure and the time in which nobody in our family is sick, but the window for such a thing is disappearing, and I am so very tired. And sick, again. There was about five minutes on Friday when I wasn’t, and then cold symptoms returned on Saturday morning shortly after my child threw up in a shoe store, which was a brand new milestone for all of us. But nevertheless, Easter was had, a holiday we celebrate for its pagan roots and not the Jesus bits. We’re all about the eggs, and the new life that comes with spring—I met a baby today who turns two weeks old tomorrow, and she was a miracle unfolding. We had a lovely visit with my parents, and saw friends on other days, and Harriet and Iris got the new Annie movie on DVD, and Harriet has watched it five times already. There are crocuses across the street. We are assembling our playlist, a CD of driving tunes for the journey from Berkshire to Lancashire (which I’m the smallest bit nervous about, Iris having just now decided that she hates cars. “Car, no. Car, no.”)

We leave for our trip this week, and I keep waiting for that lull between our departure and the time in which nobody in our family is sick, but the window for such a thing is disappearing, and I am so very tired. And sick, again. There was about five minutes on Friday when I wasn’t, and then cold symptoms returned on Saturday morning shortly after my child threw up in a shoe store, which was a brand new milestone for all of us. But nevertheless, Easter was had, a holiday we celebrate for its pagan roots and not the Jesus bits. We’re all about the eggs, and the new life that comes with spring—I met a baby today who turns two weeks old tomorrow, and she was a miracle unfolding. We had a lovely visit with my parents, and saw friends on other days, and Harriet and Iris got the new Annie movie on DVD, and Harriet has watched it five times already. There are crocuses across the street. We are assembling our playlist, a CD of driving tunes for the journey from Berkshire to Lancashire (which I’m the smallest bit nervous about, Iris having just now decided that she hates cars. “Car, no. Car, no.”)

Tonight we’re watching the new Mad Men, which premiered last night, but we watch it on download from iTunes so are behind the people who watch it on TV. I don’t know what I’m going to do in a world without Mad Men, a show that has been such a huge part of my life for years now and which has seriously informed my reading life too. It’s a good time to re-share The Canadian Mad Men Reading List, which I made last year, and am seriously proud of. Oh, Stacey MacAindra. Maybe I’ll finally get around to finishing The Collected Stories of John Cheever. I still haven’t read “The Swimmer.” I’ve been saving it, I think, of the post-Mad Men world. In which I am probably going to go right back to Season One.

Tonight we’re watching the new Mad Men, which premiered last night, but we watch it on download from iTunes so are behind the people who watch it on TV. I don’t know what I’m going to do in a world without Mad Men, a show that has been such a huge part of my life for years now and which has seriously informed my reading life too. It’s a good time to re-share The Canadian Mad Men Reading List, which I made last year, and am seriously proud of. Oh, Stacey MacAindra. Maybe I’ll finally get around to finishing The Collected Stories of John Cheever. I still haven’t read “The Swimmer.” I’ve been saving it, I think, of the post-Mad Men world. In which I am probably going to go right back to Season One.

Today I found a poem about motherhood, bpNichol Lane, Coach House Books and Huron Playschool, written by Chantel Lavoie for the Brick Books Celebrating Canadian Poetry Project. I find myself struck by the poem and the various ways it connects with my life, and how literature and motherhood and the fabric of the city are all so enmeshed. Particularly in this neighbourhood.

And finally, I am in a peculiar situation book-wise. I don’t know what books to take with me on vacation. Now, on a certain level, bringing any books on vacation is simply stupid because all I ever do when we go to England is buy books. And when I look at my to-be-read shelf now, no contenders jump out on me—nothing good for an airplane, nothing I am truly destined to love, no book with which I’d be thrilled to be holed up with in an airport terminal. You can’t take chances in a situation like this! So I have decided…to bring no books with me. This is truly the wildest and craziest thing I’ve ever done. This year, at least… To pick up a book at the airport, and trust I’ll find the right one there, and then live book to book. No safety net. This is terrifying. And yet potentially exhilarating, rich with adventure. The book nerd’s equivalent of jumping out of the sky.

April 5, 2015

Circle of Stones by Suzanne Alyssa Andrew

Suzanne Alyssa Andrew’s Circle of Stones is a novel in fragments, the story passed like a baton from one character to another, each one adding something essential to the overarching plot in addition to the peculiarity of their own perspective. It’s a tenuous arrangement, but it holds because of the solidness of Andrew’s prose, the rootedness of her characters, and her deftness at creating mystery and suspense by arranging the puzzle pieces of her novel just so.

Suzanne Alyssa Andrew’s Circle of Stones is a novel in fragments, the story passed like a baton from one character to another, each one adding something essential to the overarching plot in addition to the peculiarity of their own perspective. It’s a tenuous arrangement, but it holds because of the solidness of Andrew’s prose, the rootedness of her characters, and her deftness at creating mystery and suspense by arranging the puzzle pieces of her novel just so.

The overarching plot involves a pair of star-crossed lovers. Nik, a talented art student, is drawn to the enigmatic Jennifer, painting her features over and over in order to hold her in a way he knows he never can. Though he tries. When she disappears from his apartment in Vancouver, taking her dance bag but nothing else, leaving her cell-phone behind, he decides to go after her, against everybody’s advice—except for his grandmother, who’d urged him to be the one good man in their family and take care of the people he cares about. But Nik’s good intentions are thwarted by a violent thug who also appears to be on Jennifer’s trail. He quickly loses control of the plot altogether.

The plot is then taken up by Nik’s former roommate months later in Toronto, trying to sort out the broken pieces of his life (and here, Andrew underlines that the spaces between us are what connect us after all). Aaron has RCMP officers appearing on his doorstep asking questions about Nik, plus he’s struck by a meeting with his English professor, an annotated copy of The English Patient. Next up is the Prof herself, distracted by updates from her estranged sister about their dying mother. And then the story is taken up by a Nurse at the dying mother’s long-term care, Tina preoccupied by her Lhia, troubled teenage daughter, and something strange going on amidst the staff at work. The following chapter is from Lhia’s perspective as she negotiates her independence and sense of self as she goes into the world. On the streets of Ottawa, she meets up with Nik, who’s been on the run for awhile. And we’ve been catching glimpses of him and Jennifer in the periphery of the previous chapters, and have been able to piece together their separate trajectories, filling in the blanks.

Next is George, teenage Lhia’s uncle, a gay civil servant trying to live the good life on contract, trying to keep ahead of the place he came from but living paycheque to paycheque (when the paycheques even arrive). And then his friend, Lucy, whose story I’d read years ago as “Extreme Ironing” in Taddle Creek magazine. Suffering through grief at the death of her mother, determined to fill in the gap of her loss by taking care of her father, having his shirts sent across the country so she can iron them (on the Montreal subway no less, a guerrilla manoeuvre). I will admit that by the time we get to Tim, Lucy’s brother, a documentary filmmaker, the story seems to have circled a bit too beyond its point of origin, so it’s with relief that we find, in the following chapter, the circle narrowing again.

While the Nik and Jennifer storyline is what ties the pieces of the story together, for me they weren’t the most interesting part of the novel. They were always just a little bit too outside the frame (even intentionally so), their characters airily constructed. Some of this is deliberate—there is a scene in which Jennifer lights match after match, a vision only in the most fleeting light. But they were both a bit too ethereal to be true, whereas the other characters carrying the novel are startlingly realized in vivid, stark lines. To the point where the reader is overwhelmed, amazed that all these people—teenagers to octogenarians, men and women, gay and straight, parents, widows, the lonely and loved—have all been born from just one writer’s pen. And that there is nothing facile about what connects them—this kind of network is a simulacrum of the world.

Full disclosure requires that I note that Suzanne is a friend of mine, which only means that I was particularly pleased to like her novel so much. And it’s a demonstration of her talent that such a diversity of voices, experiences and points of view are so convincingly depicted, and that they are hung together, with mystery and intrigue, as something so remarkably whole.

April 1, 2015

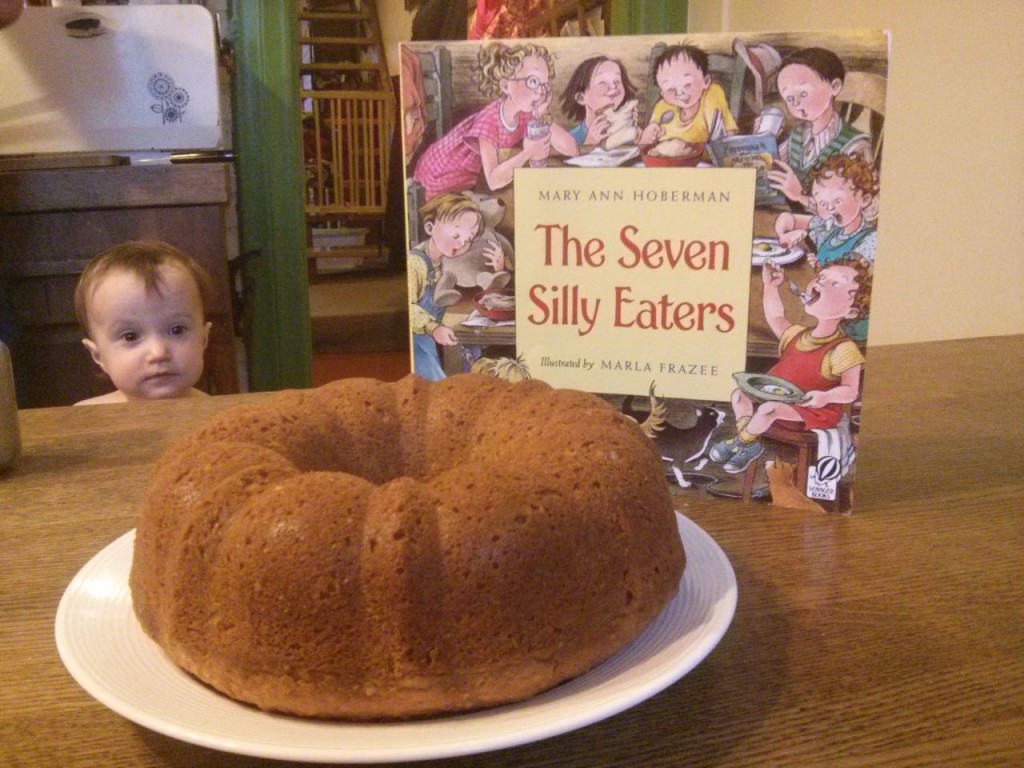

Mrs. Peter’s Birthday Cake

I’m about as crazy about literary cakes as I am about books illustrated by Marla Frazee (and written by Mary Ann Hoberman, no less), so I’ve been meaning to write about The Seven Silly Eaters for quite some time. A book that I’m actually ambivalent about, even though it has rhyming couplets. It’s down the other end of the spectrum from Mem Fox’s Harriet, You’ll Drive Me Wild, another book illustrated by Frazee. Harriet is the story of a mom who reaches her breaking point after being sorely tested, and she finally explodes at her extremely irritating (albeit loveable) daughter, and then apologizes and everything is okay. Because mothers are human. Getting angry and upset is what people do, and I think there’s nothing wrong with mothers modelling this. Imagine the child who’s gone through his entire life without learning the fact that people get upset sometimes, that one’s behaviour can have consequences; what a rude awakening the actual world is sure to be.

But then there is Mrs. Peters who seems to never have heard of birth control (with seven children in as many years) or setting limits. One by one, each of her children conspires to destroy her person and her cello-playing dreams by making ridiculous culinary demands: her first child refuses his milk unless it’s warmed to a precise temperature; her second will only drink homemade pink lemonade; third would only eat freshly made applesauce; with the fourth it’s oatmeal, unless that oatmeal has the suggestion of a lump and then he dumps it on the cat; the fifth demands homemade bread; and the twins will only eat eggs, poached for one and fried for the other.

But then there is Mrs. Peters who seems to never have heard of birth control (with seven children in as many years) or setting limits. One by one, each of her children conspires to destroy her person and her cello-playing dreams by making ridiculous culinary demands: her first child refuses his milk unless it’s warmed to a precise temperature; her second will only drink homemade pink lemonade; third would only eat freshly made applesauce; with the fourth it’s oatmeal, unless that oatmeal has the suggestion of a lump and then he dumps it on the cat; the fifth demands homemade bread; and the twins will only eat eggs, poached for one and fried for the other.

And while Mrs. Peters is happy in her bubble of domestic chaos—this is certainly the life she chose and she likes the pace—the resentment does eventually seep in. Not overwhelmingly, and she seems to accept it the way she’s accepted everything. “What a foolish group of eaters/ Are my precious little Peters,” she muses as she strains the oatmeal for the 4000th time. She thinks they’ve forgotten her birthday, and then she goes to bed sad—has there ever been anything more pitiful than that?

She should have put a stop to the whole thing years ago. “Make your own fucking applesauce, Little Jack. I’ve got a cello to play.” Mothers are people. It’s a good thing for a child to know.

But! Here is the twist. The children have not forgotten their mother’s birthday. Instead, they’ve crept downstairs in the middle of the night to make their mother all their most beloved foods—and do note that they don’t think to make her favourite food. It is quite possible that they’ve never considered that she has one. And because she gave them all a fish instead of teaching them all to fish, proverbially speaking, they have no idea how to cook anything, and so they abandon the project in the middle of it all, their dubious concoctions dumped in a pot and stuffed in the oven.

But! Here is the twist. The children have not forgotten their mother’s birthday. Instead, they’ve crept downstairs in the middle of the night to make their mother all their most beloved foods—and do note that they don’t think to make her favourite food. It is quite possible that they’ve never considered that she has one. And because she gave them all a fish instead of teaching them all to fish, proverbially speaking, they have no idea how to cook anything, and so they abandon the project in the middle of it all, their dubious concoctions dumped in a pot and stuffed in the oven.

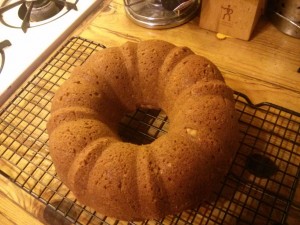

Where Mrs. Peters discovers it in the morning: miraculously, a pink and plump and perfect cake!

Naturally, we wanted to make it. The Seven Silly Eaters is a book that was born to have a recipe at the end, but there is none. Sadly. And we’re not the only people who thought so (google it: the Internet is rife with parent bloggers making Mrs. Peters’ birthday cake)—due to such a huge demand, Mary Ann Hoberman herself came up with a Mrs. Peters’ birthday cake recipe! So we made it too. Though I thought it was cheating because lemon juice in the milk (to create buttermilk) isn’t really pink lemonade, and she pinks the cake with red food colouring. So I decided to add lemon zest to the cake to make the lemon more authentic, and had the clever idea to make it pink by adding pureed beets to the applesauce (which isn’t in the recipe at all—perhaps Mrs. Peters went on to have a beetroot-loving eighth child?). My clever idea fizzled out, however, because by the time the cake was done, all the pinkness appeared to have been baked out of it. Alas. But the cake was totally delicious. Maybe not delicious enough to make up for more than seven years of domestic tyranny, but I was not asking such things from it.

Naturally, we wanted to make it. The Seven Silly Eaters is a book that was born to have a recipe at the end, but there is none. Sadly. And we’re not the only people who thought so (google it: the Internet is rife with parent bloggers making Mrs. Peters’ birthday cake)—due to such a huge demand, Mary Ann Hoberman herself came up with a Mrs. Peters’ birthday cake recipe! So we made it too. Though I thought it was cheating because lemon juice in the milk (to create buttermilk) isn’t really pink lemonade, and she pinks the cake with red food colouring. So I decided to add lemon zest to the cake to make the lemon more authentic, and had the clever idea to make it pink by adding pureed beets to the applesauce (which isn’t in the recipe at all—perhaps Mrs. Peters went on to have a beetroot-loving eighth child?). My clever idea fizzled out, however, because by the time the cake was done, all the pinkness appeared to have been baked out of it. Alas. But the cake was totally delicious. Maybe not delicious enough to make up for more than seven years of domestic tyranny, but I was not asking such things from it.

We love this book. I hope I haven’t suggested otherwise. Frazee’s illustrations are so chock full of detail that they can be explored for ages, and there are all kinds of extra-textual stories going on in the background. The family dynamic is fascinating to consider, and perhaps it’s a good discussion point for children—what happens when a family allows its mother to be treated this way? It’s a call for everyone to do her share. It’s a plea for less ridiculousness when it comes to the demands of picky-eaters. But mostly, it’s a cautionary tale for mothers, I like to think. To have limits and live inside them, to not give and give until you have nothing left for yourself. To admit that you too are a person whose needs must be met, and therein lies the negotiation of family life—a useful education for any child.

We love this book. I hope I haven’t suggested otherwise. Frazee’s illustrations are so chock full of detail that they can be explored for ages, and there are all kinds of extra-textual stories going on in the background. The family dynamic is fascinating to consider, and perhaps it’s a good discussion point for children—what happens when a family allows its mother to be treated this way? It’s a call for everyone to do her share. It’s a plea for less ridiculousness when it comes to the demands of picky-eaters. But mostly, it’s a cautionary tale for mothers, I like to think. To have limits and live inside them, to not give and give until you have nothing left for yourself. To admit that you too are a person whose needs must be met, and therein lies the negotiation of family life—a useful education for any child.

March 31, 2015

The Big Swim by Carrie Saxifrage

Books come from trees, and I’ve got this theory they never entirely shake their wild origins. I think this every time I’m reading outside in the spring and blossoms rain down on my book’s pages, or when a tiny midge appears and sits down at the end of a sentence. The poetry book Decomp by Stephen Collis and Jordan Scott was created from what remained of copies of Origin of Species that had been left in five distinct ecosystems to decay for a year, and I love that idea: of books and reading being so firmly embedded in nature, like they belong there. And in her extraordinary book of essays, The Big Swim, Carrie Saxifrage underlines this point, with references to literary pumpkins (Linus’s, Cinderella’s, and Peter Pumpkin Eater’s wife’s) in her essay on growing a 300 lb. squash; by recounting her grand awakening to the perils of climate change that came with reading—a series of articles by Elizabeth Kolbert; by explaining that she writes about climate change because it’s the one thing that relieves her heartbreak about understanding what we’re doing to our planet; and finally by making the natural world come alive for her reader, capturing the wonderfulness and wondrousness of nature in sparking, evocative prose.

Books come from trees, and I’ve got this theory they never entirely shake their wild origins. I think this every time I’m reading outside in the spring and blossoms rain down on my book’s pages, or when a tiny midge appears and sits down at the end of a sentence. The poetry book Decomp by Stephen Collis and Jordan Scott was created from what remained of copies of Origin of Species that had been left in five distinct ecosystems to decay for a year, and I love that idea: of books and reading being so firmly embedded in nature, like they belong there. And in her extraordinary book of essays, The Big Swim, Carrie Saxifrage underlines this point, with references to literary pumpkins (Linus’s, Cinderella’s, and Peter Pumpkin Eater’s wife’s) in her essay on growing a 300 lb. squash; by recounting her grand awakening to the perils of climate change that came with reading—a series of articles by Elizabeth Kolbert; by explaining that she writes about climate change because it’s the one thing that relieves her heartbreak about understanding what we’re doing to our planet; and finally by making the natural world come alive for her reader, capturing the wonderfulness and wondrousness of nature in sparking, evocative prose.

The next best thing to a tree for a tree to be, I’d say, would be any single page in this extraordinary book.

Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring meets Annie Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek meets Elizabeth Gilbert’s Eat Pray Love, with a healthy dose of Barbara Kingsolver—perhaps Animal Vegetable Miracle, a book that woke me up to the wonders of eating by the season, local food movements, and that potato have greens—who knew? In 12 absorbing, funny, and thoughtful essays, Carrie Saxifrage connects the personal with the universal and the scientific to the spiritual to celebrate her love for the world and confront her anxiety about its fate.

It’s a perfect book for spring, I think. Partly because bunnies turn up twice. The first time in “Hare,” when Saxifrage writes about tensions between “tree-huggers and rednecks” on her home of Cortes Island, BC. A friend whose family has ties to the local logging industry dares to bridge the gap between the two groups, but it all gets very complicated. (There is a blockade at one point, and Saxifrage offers muffins to everyone on sides, and I do so like that she appreciates the value of the muffin as a political tool.) A long story and good intentions lead to Saxifrage dressing up as “The Easter Hare” (not the bunny, no, this is the pagan symbol for springtime fertility) for the Volunteer Firefighter’s Easter Brunch, but things go wrong as best intentions always do, and our heroine ends up locked in a bathroom with terrifying children threatening to break down the door. In the end, Saxifrage resolves to get on side with her friend’s family by “non-controversial public service” in the future. Hopefully there still can be muffins.

In “Lagomorphic Resonance,” Saxifrage is hiking alone in Washington State, the same places she’d visited years before with a friend who’d later died: “It still felt like some remnant of Paul and me, as we had been, remained in the place itself.” And she’s there to see the pikas, mouselike creatures who are cousins of rabbits and live high up on mountains, who “seem like one of the many improbable details of the world’s enormous diversity.” The essay is partly about rumours of the pika’s endangerment, threats to its habitat by rising temperatures due to climate change, partly about her anxiety as mother of a teenager (and this anxiety hangs over a lot of the text in a really interesting way), about loss and memory, and the tremendous glory of being alone in quiet places.

The essays aren’t so much about what they’re about as they’re about narrative, and so many facts, anecdotes, sidelines adding layers of meaning to the reading experience. In the title essay, Saxifrage swims five miles in the cold ocean between Cortes Island and Quadra Island, capturing the unsexy details of such an endeavour (her entire body covered in lanolin to protect against the cold) and the thrilling ones, about the pleasures of swimming and its movements, of immersion, the challenges of endurance. It’s one of the best bits of swim-lit I’ve ever read: “Romantically speaking, I’m part ocean mammal. I spend time thinking about how real mermaids would actually swim… I’m strongly related to the marine branch of the family tree.” And why does she she partake in the splendid agony of these five mile swims? Because they permit her to “belong…to a vast, cold world where brilliant seaweed banners wave in exultation.”

(So yes, my love of this book also isn’t just because of what the essays are about, but because of how the writing is so incredibly good.)

In “Pumpkin People,” Saxifrage attempts to make her way into the community on Cortes Island where she has arrived as a homesteader (and one who was previously an American lawyer, no less…) by participating in the annual ritual of growing outsized gourds; in “Hail Mary, Shining Sea” she is awakened to the reality of climate change and its threats to the planet, this idea mingling with notions of “goodness”; pursuing a low-carbon lifestyle, she and her husband eventually stop flying, and so it’s by Greyhound bus that she makes her way to Mexico for adventure and Spanish lessons and to be part of a shining sea in a metaphoric way. “Deep Blueberry Gestalt” is Saxifrage hiking through Vancouver’s Strathcona Park alone while reading Arne Naess’s ideas about “possibilism”: “that we must decisively come up with our view of life and find meaning in it, yet remember that more things are possible than we can imagine.”

In “The Oolichan and the Snake,” she attempts to understand First Nations opposition to the proposed Northern Gateway Pipeline by taking the Greyhound for 20 hours to Kitimat in Northern BC to listen to First Nation testimony. “A lot of people don’t understand how industrious our people really were,” explains Gerald Amos, an elder of the Haisla Nation. “On this river alone, we estimate that our people harvested 600 tonnes of oolichan in the springtime. This went on for untold generations. We’ve made our living here for thousands and thousands of years without destroying it.”

“Nectar” is a beautiful story of Saxifrage’s mother’s final days, and contains one of the loveliest lines I’ve ever read: “Maybe when you love someone…you are preparing for a moment you don’t even realize will come.” “Falling into Place” is about a confluence of her mother’s death with the discovery of an ancient human jawbone on their property. “Journey to Numen Land” I loved because Saxifrage decides that sleeping a lot is radical, and she attempts to draw connections between her sleeping and waking life to fascinating ends. She returns to the water in “River Creatures,” rafting through the Grand Canyon and swimming (of course!) part way, making connections between her mother, the fossilized creatures in the canyon walls and river guides who’d gone before her: “None of them got to preserve for all time what they loved, or even completely determine their own course. Like me, they had the opportunity to study the rapids, choose their path, and find joy in the river’s firm embrace.”

March 29, 2015

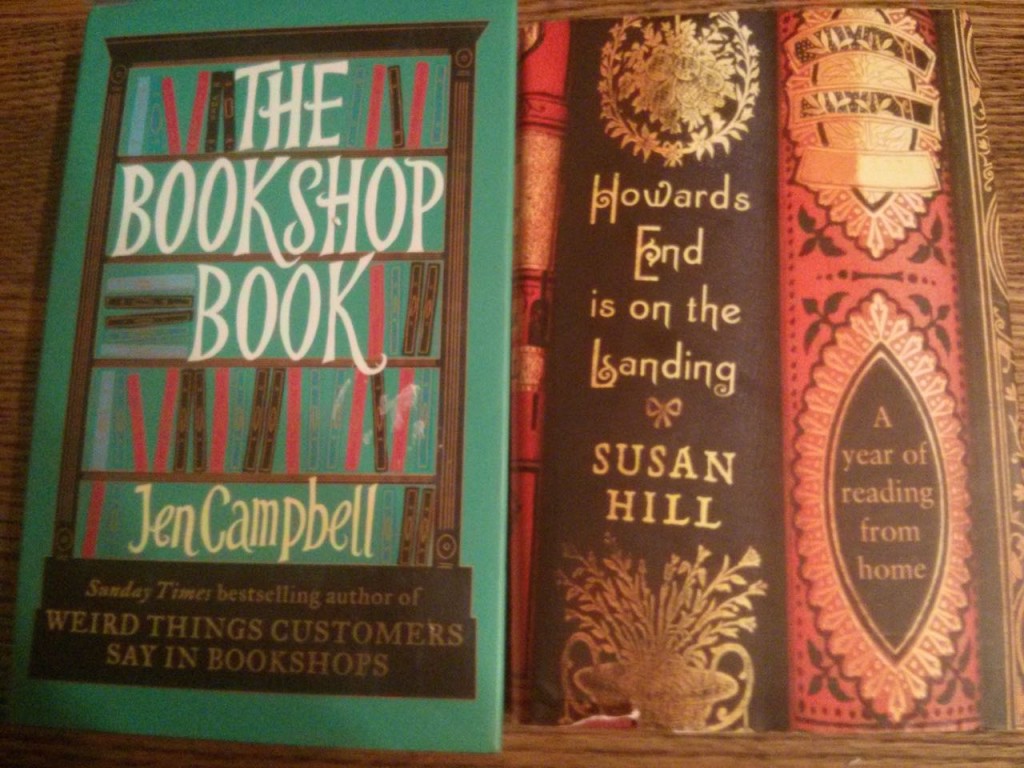

Preparations for Travel

The first step in getting ready for our trip to the UK next month is revisiting these bookish volumes which will no doubt inform many of our adventures!

March 29, 2015

Easy, healthy, delicious wholewheat banana pancakes

On the occasion of it being Sunday, I wanted to share with you my recipe for the easy, healthy, delicious wholewheat banana pancakes I make for my family every Sunday morning (while reading the paper, of course), once I finally manage to get out of bed. This recipe has so thoroughly been adapted that it’s totally mine. And now it also can be yours!

On the occasion of it being Sunday, I wanted to share with you my recipe for the easy, healthy, delicious wholewheat banana pancakes I make for my family every Sunday morning (while reading the paper, of course), once I finally manage to get out of bed. This recipe has so thoroughly been adapted that it’s totally mine. And now it also can be yours!

It’s a very forgiving recipe with measurements so exactness is not required (and banana size may vary, so that’s a good thing). Basically, if the batter is too gloopy, add more flour, and if it’s too thick, add more milk until you reach your desired consistency.

Serves 2 adults and 2 children, with a couple of pancakes left over. The children will have eaten the leftover pancakes by lunchtime if you leave them out on the counter on a plate.

Ingredients:

1 cup of buttermilk (a tablespoon of lemon juice turns milk into buttermilk)

2 eggs

2 or 3 ripe bananas, mashed

1 cup of wholewheat flour

2 teaspoons of baking powder

1/4 teaspoon of salt

Coconut oil (which we only use because it’s trendy, but vegetable oil will suffice)

Directions:

1) Whisk buttermilk, eggs and mashed bananas together in a medium-sized bowl.

2) Add the dry ingredients and whisk until the batter is smooth.

3) Melt 1 tablespoon of coconut oil in whatever pan you happen to have.

4) Add 1/4 of a cup of batter to the pan once the oil is hot (i.e. sizzles when you flick some water at it). Add a few other 1/4 cups, leaving room between pancakes. Pick up the newspaper and read an article or two.

5) Flip the pancakes when bubbles have appeared on the top and/or edges are browned and/or when pancakes are formed enough for easy flipping.

6) Don’t worry if they’re a little overcooked—the maple syrup will eliminate any problems with that. Read more of the paper while cooking for 2 or 3 minutes until the bottom side is browned, and then remove from the pan.

7) Repeat with the rest of the batter.

8) If you finish reading the paper, enjoy in the company of a good book. Serve with maple syrup and fresh fruit. And tea. Always tea. (Below is a photo of my last Sunday. It was a good one.)