March 19, 2024

The Afterpains, by Anna Julia Stainsby

Anna Julia Stainsby’s debut The Afterpains has been a hot topic of conversation in one of my group chats lately, so I was happy to get my hands on a copy and check it out for myself. It’s the story of three women and their respective experiences of motherhood and loss woven together with those of the people who love them, a testament to love and friendship, first and foremost, and the transformative possibilities of both. It’s the story of Isaura, whose teenage pregnancy was part of a long family history that seemed like a curse, and how she had to leave her daughter behind in Honduras while she travelled to New York to earn a living to support her child. Nineteen years later, the two are living a pretty good life in Toronto and it seems like daughter Mivi—on a cusp of heading to university to pursue her dream of being a doctor—has managed to defy the odds of the matrilineal curse, which Mivi is particularly grateful for because she happens to be in love with Eddie and the second part of the curse necessitates the man involved dying suddenly. Meanwhile, Eddie’s mother, Rosy, is still steeped in the grief of the daughter she’d lost to SIDS twenty years before, a trauma that has kept her too afraid to ever get close to her son, to allow herself the possibility of such a loss ever again. This is a story of grief, love and loss, what it means to have a child who is far away, or no longer alive, or growing up and away from you, which is just as it should be, but also excruciating and wondrous at once.

March 19, 2024

The Leap! (New Bookspo!)

The third episode of BOOKSPO is up, and it’s particularly special to me because…it was also the first interview I did for this project, at the end of January. Back when I knew absolutely nothing about how to make a podcast, back when my self-esteem and confidence were at remarkable lows, and I knew that making the podcast would help me find my way out of that low. But making the leap to doing that was scary. There was something paralyzing about where I was at that point, creatively, and making any leap seemed terrifying and impossible. I felt really intimidated about approaching authors for interviews because I didn’t know what I was doing, and performing that vulnerability just seemed too much to ask of myself. I wasn’t sure if it was even possible, if I’d be able to pull off the podcast at all. My first interview would be a kind of trial run, and I needed a safe place to land for that, and a kind person to work with, and Shawna was the only one. The person I trusted enough to be vulnerable with, to have faith in the thing I was trying to make, to bright thoughtfulness and beauty to the process.

I am so grateful to her now, and can honestly say that none of this very neat thing I have made would have been possible without her. And I hope you’ll enjoy our conversation as much as I did.

March 18, 2024

The Gift Child, by Elaine McCluskey

With her seventh book, The Gift Child, short story superstar Elaine McCluskey has pulled off a novel that’s as great as one of her sentences, which is saying a lot. It’s a novel in the form of a memoir by Harriett Swim, a photojournalist who lost her career when the bottom fell out of the industry, and lost her marriage around the same time for reasons she’ll eventually make clear, which is also to say that she is struggling. Age 52, she’s returned to her hometown of Dartmouth, NS, where she’s got a job at the casino and can’t help getting sucked into the vortex of her father, Stan, iconic news anchorman, philanderer, narcissist, pathological liar, and jerk. But does the story of what’s wrong with Stan and all his various crimes have to do with who Harriett is? And what about her cousin Graham, a bit slow, last seen riding a bicycle with a giant tuna head in the basket and missing ever since? What if it’s easier to get to the bottom of the mystery of what happened to Graham, what happened to Stan, than to unpack the reality her own trauma and heartaches? (“Focusing, as people often do, on the peripheral, because the real problem was too unmanageable.”) What if family ties weren’t necessarily destiny? But then, if that were true, what would explain it all? What stories would we tell?

This is a novel ostensibly made of bits and pieces, and diversions, but it’s also fundamentally a poignant journey to the heart of things. Further, it’s an assemblage of the weird and wonderful—aliens; Dartmouth separatists; an exploration of the culture of “paddling,” which I never even knew was a sport; off-colour adventures of the down and out; the crime beat; Russian spies, and hockey heroes. I loved it all so much.

March 15, 2024

Routine Interrupted

This message is coming to you from outside of routine in a variety of ways, the first being that it’s not due until the end of the month, but I’m spreading things out so that, going forward, my Pickle Me This Digest (a monthly compendium of my blog posts) arrives in inboxes mid-month, my essays come at month-end, subscribers don’t get end up forgetting about me, or getting fed up with all my newsletters arriving at once.

Because it’s not been long since my last Pickle Me This digest, this newsletter is shorter than usual, which is probably for the best since—also outside of routine—it’s March Break and my children are on holiday. I’m fitting my work into half-days and adventuring with my kids in the afternoons. We’ve been to see the Nature’s Superheroes Exhibit at the Royal Botanical Gardens in Burlington, to Leslieville for Queen East shenanigans (including a visit to Queen Books!), and to the Aga Khan Museum for the Night in the Garden of Love exhibit (it was so great—and so easy to get to on transit from the 100A bus from Broadview Station!). We also went to see The Mighty Ducks at Paradise Theatre. It’s been the perfect combination of low-key and FUN. (My specialty is stay-cation visits to places that are never crowded… ever since that one time I went to the Science Centre on a PA Day, a day that will live on infamy and that my daughters will be addressing with their therapists well into the next century…)

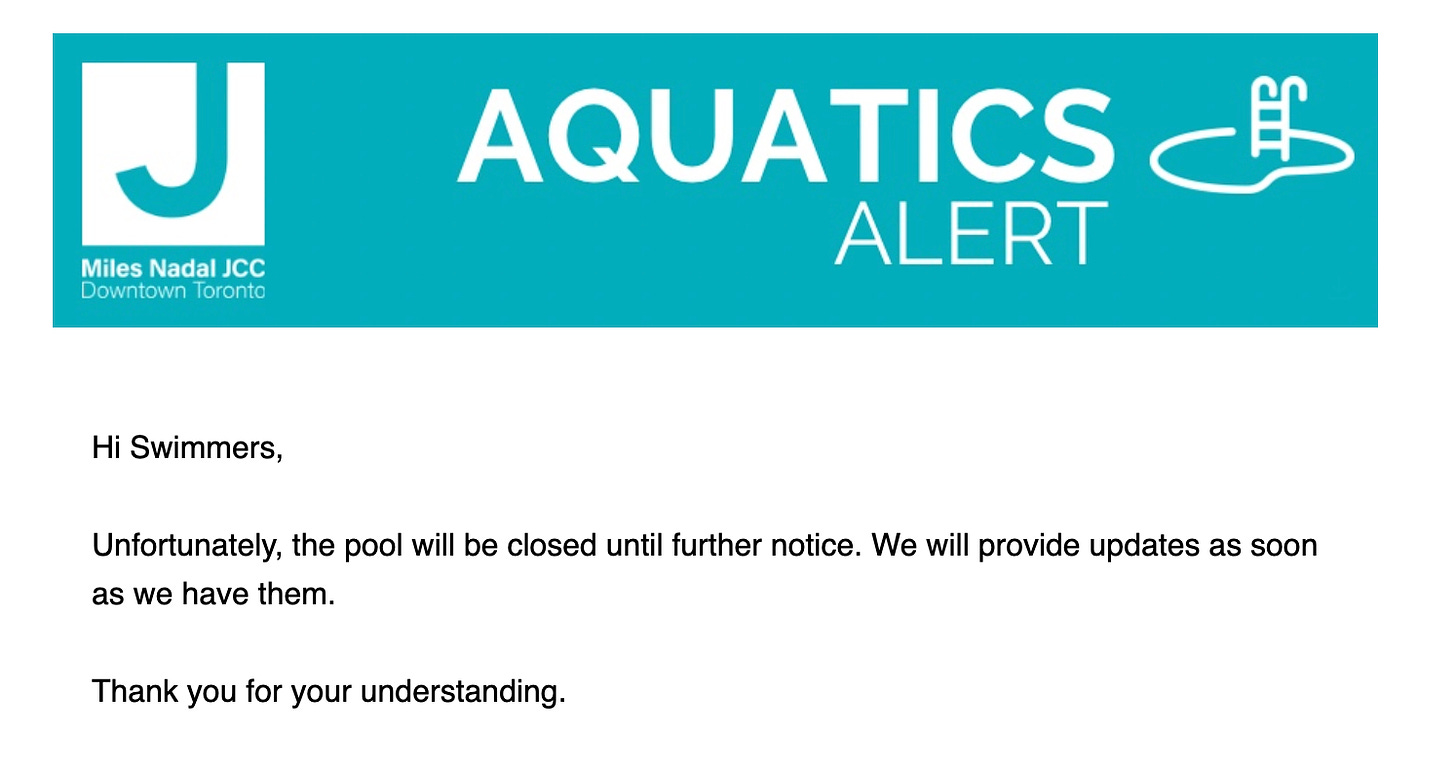

The most essential element of my routine being interrupted, however, is that I received this message in my email inbox last Tuesday:

It turned out that a light fixture crashed down from the ceiling over the pool deck, shattering glass all over the deck and into the pool itself. (Thankfully no one was hurt.)

Notices of pool closures “until further notice” have destroyed me in the past (as I wrote here, I blame that on a period of precarious mental health and having recently read The Swimmers, by Julia Otsuka), but I’m in a fairly stable place these days and also have a closed-pool contingency plan, which is the nearly brand new and incredible Wellesley Pool, just twenty-some minutes away from my house by public transit. That I’d be working half-days, however, meant I wouldn’t be able to swim during the day (which is my usual plan) and so I resolved to get up early and head west on the subway before sunrise*…even though this is the week the clocks have sprung forward so it’s even earlier than early. (I have never been a morning person.)

*Okay, about fifteen minutes before sunrise, but still.

I love swimming, but I’ve never had occasion to discover if I loved it enough to wake up before sunrise and take a ride on the subway. My usual pool is very conveniently situated halfway between my house and my child’s school, which means I pick her up every afternoon with my hair wet (this is why they invented hats!) and I don’t have to go out of my way to swim at all.

But it turns out that going out of my way, as I have this week, has not just wonderful, but even magical? Leaving the house while the sky is indigo (though it gets lighter and lighter with every passing day—the sun rose three minutes earlier today than it did on Monday). Getting on the subway when everything is still quiet, the city buzzing with a calm and quiet hum. All the most terrific communal aspects of public transit without the rush hour stress and fuss, humans at their most wonderfully human, today with spilled milky coffee spreading across the train floor like a Jackson Pollock painting, passengers engaged in a delicate dance to avoid it. And then a walk down Sherbourne Street, which is never dull, and arrival at a pool where anybody who wants to is welcome to swim for the free. The water is much cooler than at my usual pool, and it’s been refreshing, along with the swimming itself, an investment of energy that always pays back in dividends, the goodness I feel in my body for the rest of the day.

It has been wonderful and magical to discover a little surplus time in my day, especially during this season of daylight austerity; to realize that a little trip across the city is closer than I think; to connect with a neighbourhood and people who are new to me; to find out that I really do like swimming that much. I really do!

And I look forward to a return to my regular routine on Monday when the pool is scheduled to open again (fingers crossed) but I’ve enjoyed my time outside it very very much.

March 13, 2024

Home, by Toni Morrison

“It’s only been in the last few years that I’ve started to read the novels of Toni Morrison—Beloved, Sula, Jazz, and just recently her debut The Bluest Eye—and for me, this has been a process of becoming, of watching the possibilities of literature unfolding. Mesmerizing, and also disorientating. I’ve found understanding these novels to be difficult. The kinds of places where the bottom land is high up on the hill. Where the unsaid is articulated, where the wicked are permitted sympathy and understanding. Whose love is a kind of gutting desperation, an urge toward destruction. Stories that are strange, true, and irreducible…”

In the two years since I wrote those words (in a mini-essay I just loved writing) I’ve continued to make up for my Morrison deficit—I’ve since read read SONG OF SOLOMON, PARADISE and now HOME, that last one under the influence of Donna Bailey Nurse who posted about it on the last day of Black History Month: “Morrison jazzes our idealistic image of 1950s America. She scratches the sepia-toned album of post-war prosperity, small-town security, domestic bliss, and the nuclear family.”

HOME seems to me more straightforward than Morrison’s earlier books, but that doesn’t mean there’s not a whole lot going on beneath its surface, in the space between the lines. Between the actual chapters even, as Korean War vet Frank Money—”An integrated army is integrated misery. You all go fight, come back, they treat you like dogs. Change that. They treat dogs better.”—engages in dialogue with the author writing his story (“You can keep on writing, but I think you ought to know what’s true.”) The story of his journey through 1950s’ America to come to the aid of a beloved younger sister who’s in trouble, a journey whose obstacles include trauma, addiction, vagrancy, bad luck, and violent racism. A brutal story underlined by extraordinary gentleness and so much love.

*If you too have a #ToniMorrison deficit, I think HOME would be a great place to start remedying that.

March 11, 2024

Bury the Lead, by Kate Hilton and Elizabeth Renzetti

“There’s nothing to worry about, Glenda. It’s just routine. There’s no way the cops will think a butter tart feud is enough motive to kill someone. This isn’t Midsomer Murders.”

I first read BURY THE LEAD back in January in preparation for Bookspo Podcast (the episode went live last week!) and returned to it again this weekend as I’ll be interviewing co-authors Kate Hilton and Elizabeth Renzetti (who are friends of mine) as part of House of Anansi Press’s Beer and Book Club at Henderson Brewing this Wednesday March 13. And it’s something to read a mystery novel a second time, when you already know whodunnit, and can pay attention to how the machine is working, all the moving parts. For some books, that might take all the fun out of the experience, but not this one, which I liked even more the second time around. I loved the humour, the similes (the old newspaper that “looked like it had been typeset with a machete”), the fact that it’s concerned with newspapers at all (veteran journalist Renzetti brings her years of experience at the Globe & Mail, and a passion for locals news and journalists in general), the fierce feminism, the small-town Canadian cottage-country setting. It’s the story of Cat Conway, who’s turned up in Port Ellis (where she’d spent summers with her grandparents years before) on the burnt out trail of a marriage and a career both gone out in flames. Very soon, however, it seems that her new, smaller, quiet life is not going to be so quiet after all when the lead in local theatre production (who is a world-famous actor) turns up dead on opening night, and not of natural causes. Ever the reporter, Cat is determined to get to the bottom of the story, along with her posse of news colleagues, a motley bunch if ever there was one, except that it seems like somebody in town is intent on getting between Cat and the truth. But is there anyone more indomitable than a middle-aged woman fuelled by rage who has nothing left to lose? Bury the Lead is pure delight.

March 9, 2024

Both sides brought large speaker systems and screamed

I didn’t observe International Women’s Day in a public platform sort of way. (I did re-watch Hidden Figures with my family, however. Would recommend.) This was not a conscious choice, but when I opened Instagram yesterday morning and the first post I saw was a woman screaming about all the people not included in her feminism, my brain said Nope. Nope. Instead of posting about feminism on the 8th of March, instead of yelling about my politics, I’m striving to embody those politics every day of my life, to live them. Which is more subtle than a soapbox. It occurred to me that it’s been a long time since I posted anything on social media about abortion, which makes me uncomfortable. Embodying politics instead of screaming about them is not the same as staying quiet and being polite, but sometimes it looks the same. Maybe even the effects are the same, which is counter to the way I want to live my life, but all of this introspection has come about because I’m not convinced that yelling gets great results either. Also, as no doubt many are thinking, there are just three people left on the planet who don’t know my stance on abortion anyway. I have nothing new to say on the matter, just as I have nothing new to say about International Women’s Day, about women matter, why intersectionality matters, why feminism is necessary, why a world that’s good for women is good for everyone. I am so tired of reciting the same slogans over and over, the way the repetition comes to rob the words of meaning. The way they mean something when we first hear them, when we first say them, but then we cease to think about what those words mean, and then we cease to think altogether. The absurd theatre of it all, rather than anything substantive. “Both sides brought large speaker systems and screamed duelling chants at each other.”

I keep returning to this, from Rebecca Woolf: “It is in our best interest as a species to hold each other up through the complexity of our feelings instead of pushing each other down. While this moment demands ACTION — and I believe it does — it is also necessary for people in mourning to feel validated in their grief. All the energy being spent on attacking and unfollowing and disparaging each other online can and should instead be spent validating our own feelings and giving ourselves the space to move through them. Denying ourselves the time and space to do so will result in resentment and emotional constipation. (I am seeing this happen with people I know in real time.)”

“All the energy being spent on attacking and unfollowing and disparaging…can and should instead be spent validating our own feelings and giving ourselves the space to move through them.”

Woolf wrote this in the aftermath of October 7 2024, but I think it applies to everything. And yes, “validating our own feelings and giving ourselves the space to move through them” sounds very airy-fairy ’90s Oprah, and maybe some would argue that this is actually inaction, inertia, but are large speaker systems and screaming duelling chants (and self-righteous contempt) any more productive?

March 8, 2024

The Hunter, by Tana French

Tana French is my favourite. Her new novel, The Hunter, is the second book in her new series featuring Cal Hooper, a retired Chicago detective who buys a rural home in the west of Ireland to discover that the big city’s got nothing on the village of Ardnakelty in terms of darkness and depravity. I read the first book, The Searcher, in 2020 and then forgot everything about it, but no matter because The Hunter doesn’t require a reader to be wholly up to date. And I will likely forget everything about The Hunter too because, as with when I read any mystery novel, but especially Tana French’s, I’m more just steeped in the atmosphere than sorting through the details. And the atmosphere is HEIGHTENED in this latest release, set during a sweltering summer as crops fail and everyone’s on his very last nerve. Cal has created a healthy relationship with local teen Trey Reddy, but it’s all set to go awry when Trey’s father reappears after years away in the company of an Englishman who’s probably not what he seems, and when the locals try to pull one over the both of them, it might just be that they’re being swindled themselves, and just when Cal thinks he’s got a handle on things, a dead body turns up in the road on the mountain. Could not love it more. My only complaint is that now I can’t stop saying “Feck.”

March 6, 2024

Transgressions

It had to happen sooner or later, because it hadn’t happened in more than a year, but my pool has closed “until further notice” due to a light falling from the ceiling and smashing on the pool deck, shards of glass in the pool which now needs to be drained, etc. etc. And instead of having a complete nervous breakdown like I did when the pool had to close for a few weeks in 2022 (I blame it on a period of precarious mental health and having recently read The Swimmers, by Julia Otsuka), I am being stoic and patient (okay, it’s only been 16 hours, but I’m hanging in there) and taking the bus to the community centre at Wellesley and Sherbourne to swim in the pool there, which is a great pool, but the point of this story is that has a universal/non-gendered change room. Which, when I used the pool previously, has been absolutely a non-story, and I actually appreciate the non-gendered aspect as opposed to my usual pool where people lie down naked in the steam room with their legs wide opened so I can LITERALLY see right up their butt holes. All butt-holes must be covered in the non-gendered change room, where we get changed in private stalls and everyone is required to be attired. But the other times when I’ve used this change room, it’s been the only change room available, by which I mean that there are actually two change rooms, but only one was open at a time. Today, however, both change rooms were open, and I felt slightly uncomfortable for being in an unfamiliar space where I’m not clear on routines and rituals, so I just tried to look cool and went into the change room before me. Except that everyone I encountered in the change room was a man. Now, this pool, for various demographic reasons, has way more men than women anyway, but I couldn’t help but wonder if I’d missed something and entered a men’s change room by mistake. And the whole point of all of this was JUST HOW MORTIFIED/EMBARRASSED/WEIRD I felt about potentially having done such a thing. How it tapped into something ancient inside of me that’s always been afraid of transgression, being in the wrong space, being the wrong body in the wrong space. Something ancient that doesn’t actually come up so often because inhabiting traditionally male spaces (like when I played the trombone instead of the flute, was loud instead of demure, used to get ridiculously drunk at the Pig’s Ear Tavern) has always been kind of awesome and empowering (I’ve long worshipped at the altar of Jo Polniaczek) but this was terrible and shameful for reasons I’m still not finished unpacking, and it was fascinating to experience this discomfort (as well as unpleasant). What a prison gender truly is in all kinds of ways I’m not even cognizant of.