October 5, 2017

What Happened, by Hillary Clinton

Maybe Hillary Clinton is like cilantro, and you’ve just got a taste for it or you don’t. But I do, and it’s longstanding, which I know because in 1998 I sent Hillary Clinton an email voicing my support in the wake of the Monica Lewinsky scandal, and I recall respecting her decision to not give up on her marriage. Which was kind of a weird thing for an 18-year-old to be concerned with, and not very feminist really, or maybe it is. I didn’t identify as a feminist when I was 18 anyway, and I spent the 1990s’ as a middle aged woman in a teenager’s body, plus there just wasn’t a lot going on on the internet at this point and so sending emails to the White House was how one passed the time.

Hillary Clinton’s 2003 autobiography Living History was the very first book I ever wrote a review of online, during a brief period in 2004 when I had a book blog with a friend and imagined that I too could be a book blogger like Maud Newton but then it all seemed too ambitious and the book blog fizzled out. (And yes, boys and girls, I, like Hillary Clinton, am living proof that we can achieve our dreams. At least if the limits of our dreams are book blogging, I mean.) We lived in Japan at the time and I remember buying the book in the bookshop in our town that was located on top of the train station, just one of a handful of books in the entire store that was in English and therefore I had the literary skills to pick it up and read it. Books were rare then, which is funny because now I basically live in a castle constructed of them. All of that was a long time ago.

But I remember my main frustration with that book, which was Clinton’s refusal to admit her exceptionalness. Her remarkable life, she wrote, was a product of her time, of having been born in a moment where there would be opportunities for Americans, and American women in particular, as there had never been before. Her story, as she told it, was a part of a larger story, which is all fine and well, I guess, but it didn’t explain why everybody then had not become Hillary Rodham Clinton then. I mean, yes, the entire graduating class at Wellesley in 1967 was undoubtedly impressive, but she had been chosen to give their commencement address. Hers was a singular story too, and I wanted more of that.

Which is what you get in her brand new bestselling memoir, What Happened. A book in which Clinton talks about her reasons for pursuing the presidency a second time and dares to state this: “The most compelling argument is the hardest to say out loud: I was convinced that both Bill and Barack were right when they said I would be a better President than anyone out there.” If you have any idea how difficult it is to articulate something like this about oneself, you are probably a woman too.

In this book, Clinton has learned the invaluable lessons that failure has to teach us (and she learned it twice), plus she is angry, and she’s taking shit from no one. She’s no longer giving history all the benefit for her own success and for that of others. Of the women’s movement, she writes, “And it was and is the story of my life—mine and millions of other women’s. We share it. We wrote it together. We’re still writing it. And even though this sounds like bragging and bragging isn’t something women are supposed to do, I haven’t just been a participant in this revolution. I helped to lead it.”

She writes about her working going undercover in the American south during the early 1970s to find schools were segregation practices were still the norm (and there were plenty of them); of her work as a lawyer for women and families; of her successful attempts to found the Children’s Health Insurance Plans during her husband’s presidency, which provided healthcare for millions of American children and which the US government let lapse this week. A lot of this book is heartbreaking, as Clinton reflects on her plans for her Presidency and reflects on the winning candidate’s first actions in office. She reflects on her mistakes throughout her public life, on the many times she’s changed her mind, on her regrets, the evolution of her ideas. In fact, she reflects on all of these more than any man ever would, in that way that women are made to think they must do and the public only doubles down on this inclination. The double standard is incredible, and I never properly understood how systemic and institutionalized (and psychologized) it was until the American election of 2016. In some ways, learning the truth of the matter is incredible. In other ways, not so much.

And yet, this is also an inspiring memoir. It moved me to tears more than a few times. There was a moment reading this book where I felt something unlike anything I’d felt in years, which is envy for American people, for American women in particular (I know!) who had that singular experience of seeing a woman’s name on the ballot in their election for head of state and even got to place an x beside it. (Full disclosure: in our last Federal election, however, I had the amazing privilege of choosing between two exceptionally qualified and inspiring women candidates. That was also an incredible thing.)

Hillary Clinton’s mother, Dorothy Howell Rodham, was born June 4, 1919, “the exact same day that Congress passed the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution, finally granting women the right to vote.” So yes, sometimes the backdrops against which lives are shaped are incontrovertible and the connections can be uncanny. But that is only the half of it. The other have is the story of a person who is an actual human, which is say that she is an imperfect candidate. A phrase I’m still kind of obsessed with—because who isn’t? Certainly not Clinton’s running mate in 2016. But I was aware of her imperfections during the election, as no doubt we all were as a result of the biased media coverage Clinton refuses to condone in What Happened. And I remember tempering my enthusiasm for her, not wanting to speak up in support of Clinton, because to so would be invite a storm of vitriol from those concerned with her “Wall Street ties” and war crimes, those for whom she was not a taste that could even be acquired, those people who hated for all the ways in which it’s so much easier to hate a woman than a man, in all their pantsuited specificity.

But no more. Because I learned something from the 2016 American election, which is the danger of staying quiet, of being polite, of trying to please everyone. If I could take anything away from this political morass we’ve found ourselves in, it’s the courage to be half as brave as Hillary Rodham Clinton.

October 4, 2017

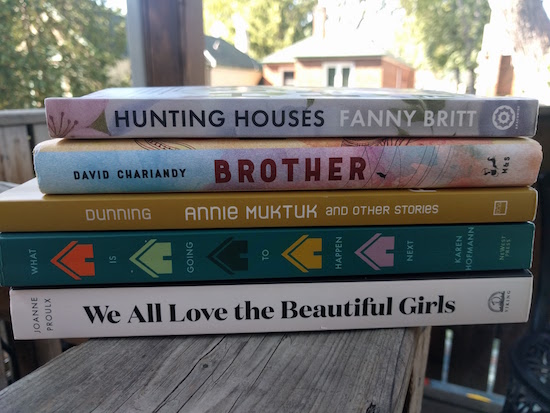

Books on the Radio!

Finalists for the Governor General’s Literary Awards were announced this morning, and the shortlist for the Scotiabank Giller Prize came out earlier this week, and the Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction prize list came out last week. Interestingly, none of the books that I’ve loved best this year are turning up on the prize lists—possibly my affection is a curse?—but I’ve been paying attention to this kind of thing long enough to know this is not something worth being bothered about. Nothing bugs me more than news stories after prize announcements highlighting what big names have been “overlooked,” or trying to be strategic about what books are nominated. Basically, it’s all very subjective, and I’m just happy that all the big Canadian prizes highlight such a wide selection of books this year. There are many titles on these lists I haven’t read yet, and I kind of love that—the possibility that they may indeed end up among the books I’ve loved best after all. Which certainly include the five titles I talked about on CBC Ontario Morning today. You can listen again on the podcast—I come on at 25 minutes.

October 3, 2017

Snacks: A Canadian Food History, by Janis Thiessen

As soon as I heard about Janis Thiessen’s book, Snacks: A Canadian Food History, I knew I’d want to read it, for so many reasons, not least of all because I’d necessarily have to purchase snacks in order to authentically Instagram my reading experience. Props, I mean. Plus, basically I’ll do almost anything to justify a bag of potato chips. I knew the book would inevitably lead to the purchase of cheezies: “It’s for work,” I’d tell the sales clerk, making sure to save my receipt. “The things I do to support Canadian and books and literature”, I’d self-congratulate, all the while licking orange cheese dust off my fingers. And all of this pretty much perfectly transpired, with the added bonus of the book being fascinating.

Now, if you cannot fathom how a book about the history of snack food might be fascinating, then I’m not going to try to win you over, but if Snacks already sounds intriguing to you, you won’t be sorry. Thiessen begins her book by placing snack food in the context of contemporary food culture, which stresses health and wellness, all things “natural” over processed, and sees fit to gloss over class, gender and labour issues in the ways we value and talk about food. She writes about the role of snacks in her childhood, which made me think a lot about the potato chips that were a fixture of my life when I was growing up—and how my Dad’s glove compartment was always packed with Bazooka bubble gum. She gives an inventory of her own family’s pantry, and challenges the vilification of snack foods in several interesting ways.

I wanted to buy a bag of Old Dutch potato chips to accompany my Hawkins Cheezies, but tracking down a bag here in Ontario would prove surprisingly difficult. Or not so surprising, I would learn, as I started reading about the Potato Chips Wars of the early 1990s (which were really a thing!) in which Old Dutch tried to expand into Eastern markets and Hostess Frito-Lay would go into Toronto stores and buy all their Old Dutch stock, promising discounts on their products if they didn’t sell Old Dutch again. My husband finally tracked down a bag at a convenience store on Bloor near Bathurst. Previously, he’d seen a box of 50 mini chip bags on sale for Halloween, and I admonished him for not buying the box—it was portion controlled, I pointed out. We could have kept the box around and had chips for weeks and weeks, except that we then devoured the one bag of chips he did buy so thoroughly that I realized no chips were safe in our midst. It was honestly fascinating to learn more about the history of the potato chip though, its industrial and agricultural histories, about the consolidation of potato chip companies in Canada, that Old Dutch, that Canadian mainstay, isn’t even actually Canadian….

Neither is Hawkins Cheezies, I was shocked to learned, or at least it didn’t start out that way. Hawkins began as a big American snack food company that fell apart due to scandals connected to divorces and Mafia ties, and what was left of the company was a plant making cheeses in Tweed, Ontario, whose business has remained unchanged for more than half a century. There is a mythology around these products, a national mythology too, and Thiessen probes these to interesting ends. Her research consists of oral stories by plant employees, getting at the labour side of snacks in a way that most food discourses neglect to. Readers learn about the experience of working at or managing Old Dutch and Hawkins plants, and other food companies, as well as candy, chocolate and biscuit factories. (Interesting fact: huge risk of fire and explosion in candy factories. Who knew?) Other companies Thiessen writes about include Paulins, Moirs (whose 1980s’ commercial for Pot of Gold I remember well…) and Ganong, Robertson’s Candy, Cavalier Candies, Purity Factories, and Scott-Bathgate.

The book’s last chapter is about a game show produced regionally across the Canadian Prairies in the 1960s called Kids Bids, wherein children were encouraged to save wrappers from Old Dutch potato chips and then bring in their collections to the show to bid on coveted items—top prize was a bicycle. Exploitive and unhealthy, perhaps, but Thiessen shows how the show gave children agency and opportunities…and basically eliminated litter from chip bags. Oh, those were the days…

October 2, 2017

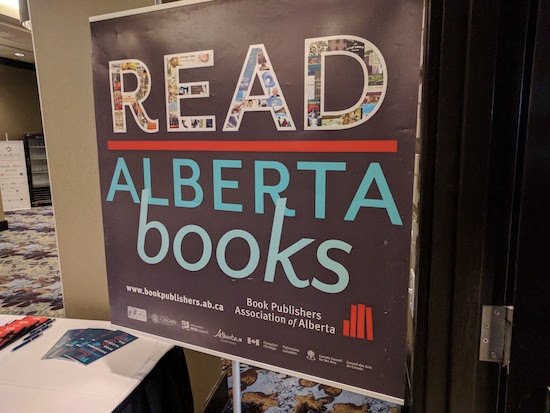

Pickle Me This goes to Edmonton

I lost my umbrella when I was in Edmonton, possibly in a bookshop, or somewhere en-route to the Hotel MacDonald, where I got to have fancy drinks with writer and blogger extraordinaire Shawna Lemay. So does that make it a literary lost umbrella, I wonder, even if it didn’t happen in fiction? Although I include the umbrella Virginia Woolf lost on a bus, and that wasn’t fiction either. Does it still count as a literary lost umbrella if it’s pocket-sized? Pocket-sized umbrellas just don’t seem all that literary. But they are particularly easy to lose.

Umbrella losses aside, however, as well as a minor mishap where I drank too much tea and managed to poison myself and spent an afternoon in bed in my hotel room, I had a wonderful time in Edmonton. (This was about two weeks ago. I’m a bit behind, blog-wise, and working hard on catching up.) I was invited for the Book Publishers Association of Alberta’s Annual Conference to give a presentation about why book blogs matter, and arrived in Edmonton on Thursday afternoon on a plane packed with women who were heading to some weird multi-level marketing conference for beauty products and obviously tried to convert me into their cult. (“Are you looking for your Plan B?” the woman sitting next to me on the plane was asking, and I’d never before considered how awful it would be to be trapped on a plane with people who were trying to convert you into their cult. I am still disappointed that I never thought to answer, “Are you peddling beauty products, sister? Cuz I don’t need no beauty products.”)

I had half a day to spend in a city I didn’t know yet, which is the most incredible kind of luxury, I think, in terms of time and opportunity. After finding my novel for sale in the airport bookshop (where the booksellers had even heard of it, or at least were very convincing in pretending they had…) a taxi delivered me to Whyte Avenue where I poked in shops and hung out in a Second Cup to charge my phone, and then I started walking, taking in the golden light in this place where Autumn comes earlier than it does where I live. Edmonton is beautiful, and it was a gorgeous, crisp fall day, and I had a very good time exploring on my own, making lines on a map that was new to me. When I reached the edge of the river valley, I was able to take in a great deal of the city at once, and it was gorgeous. I stopped at the High Level Diner for dinner, and it just happened to be Ukrainian night, so I got to have pirogies and borscht. And then I began my long long walk across the High Level Bridge with great dramatic clouds rolling in (see my first photo, above) and at this point I was pleased that I still had an umbrella.

As visiting bookstores is basically the reason I go anywhere, a trip to Audreys was the thing I most wanted to do in Edmonton, and it lived up to my amazing expectations. Although I must admit I’m partial to Audreys after my book was an Edmonton bestseller in April, and it was also pretty splendid to see it on the Staff Picks shelf. But even without these glorious details, I would have been happy to spend time browsing in Audreys, where I managed to find perfect gifts for each member of my family, and I bought Jen Powley’s memoir Just Jen and Claire Kelly’s debut poetry collection, Maunder, both of which would turn out to be very good choices.

Shawna met me at the bookstore, and then we went out for drinks, and had a delightful time. We’d met briefly at Shawna’s book launch in Toronto awhile back, but not exactly properly. However she is one of those bloggers that gives you the impression—with her candour, generosity, eloquence, thoughtfulness—that you know her. And I think I really did, because we had a terrific time together, never running out of things to talk about, and I could have talked forever, except that it was getting late and I was operating after a day of travel (planes and walking) and a two hour time difference. Luckily we got to keep on talking as Shawna kindly drove me to my hotel.

I saw the sun come up the next morning—I woke up at six so I could call my children before they headed off to school. There is nothing in the world quite like a prairie sky. And then I ordered room service and read books, and prepared for my presentation later that morning, which went very well, and it was so terrific to meet people in the Canadian book world with whom I communicate often and/or have been familiar with for years. I take for granted sometimes Canada’s hugeness, and that there are also these people I’ll never have the chance to meet face-to-face and then I do meet them and realize how powerful it is to bring people together and how much our culture benefits from these true connections being made. I loved Saskatchewan poet Brenda Schmidt‘s presentation about how social media has become her workbook—I identified so completely. And it was especially nice to be there to celebrate Alberta Books when I’ve been especially fond of them lately—Annie Muktuk and Other Stories and What Is Going to Happen Next are two stand-outs. It was a privilege to be part of it all, and hanging out in Edmonton.

September 29, 2017

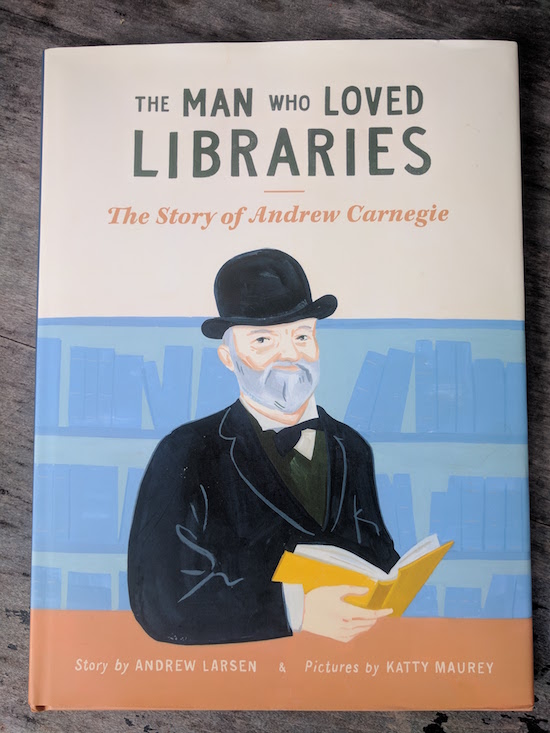

The Man Who Loved Libraries, by Andrew Larsen and Katty Maurey

Harriet has decided she’s going to be Jane Goodall for Halloween, mostly as an excuse to carry around a stuffed monkey at school, but it seemed like a good excuse for a little educating. So I put a bunch of kids’ biographies on hold at the librarian, and they all came in on Tuesday. Tuesday was the second day of a heat warning here in Toronto, a stop at the library on the walk home from school serving as a very good pit-stop. And when we got there, the place was packed, people escaping the heat, reading books and magazines, kids spinning on the spinning chairs, playing games on the computer, washing their hands in the bathroom because they were sticky from where popsicles had melted in the heat.

The library is for everyone, I was thinking as I took in the scene on Tuesday, Harriet gathering her stack of books, heading over to sign them out on the library we got for her when she was just a few weeks old. I’ve written before about how important the library was to me when Harriet was small, and our experiences with phenomenal children’s librarians underlined my children’s pre-pre-school years when I was home with them, and taught me the stories and songs that would become the foundation of our familial literacy. Our kids continue to attend library programs. We visit as a family every couple of weeks, and borrow so many books we need to bring a stroller in order to cart them home. Books and reading are a bridge between the thirty years that divides me from my children; reading books together is the one activity that we’re able to reap enjoyment from on the very same level. And the library has ensured there’s always something new for us to explore.

But the library isn’t just for us, the already book-spoiled. The library ensures that everyone has access to knowledge, to learning, to entertainment. To bathrooms too, and a place to sit down, and cool enough (or warm up, as the case may be). For a lot of kids, it’s where they get their access to computers, to the internet. It’s where people learn to format their resumes, where lonely people find company, where postpartum mothers go to give their muddy days a shape. For some people, the library is a comfortable place to sleep. They’re community centres, schools, literacy hubs. They’re about trust, community, democracy. I read a post recently where someone posited that if libraries didn’t exist and someone tried to invent one, you’d swear it would never ever work.

The funny thing that I hadn’t considered when I started this post is that I met Andrew Larsen at the library. We live in the same neighbourhood, and met when Harriet was small and he was on the cusp of publishing his second book, I think. And I would learn that he too felt the library had been essential to his experience as a stay-at-home parent, eventually leading his emergence as a children’s author. We have loved the books he’s published since, books that have delighted our family (“I read Andrew Larsen’s squiggly story today, Mommy,” reported Iris this very afternoon when I picked her up from junior kindergarten.) I’ve savoured our conversations on our walks to school together, and miss him now that his children have moved on to bigger kid things.

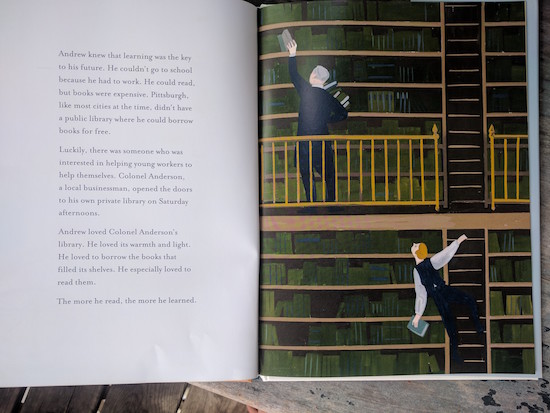

Andrew Larsen’s latest is a picture book biography of Andrew Carnegie, The Man Who Loved Libraries, illustrated by Katty Maurey who was also behind Kyo Maclear’s The Specific Ocean, another picture book we’ve loved. I’m familiar with Carnegie in theory, because he’d helped to build libraries in both of the Ontario towns I grew up in, as well as the Beaches, High Park and Wychwood Libraries in Toronto, among many many others. But Larsen’s story fills in the gaps—Carnegie was born in Scotland and moved to America as a child with his family who were looking for a better life. His first job was in a cotton mill, where he was a bobbin boy. A hard worker, he strove to get better work, and find whatever education was available to him. He made a point of teaching himself skills that would be relevant for work, but also was able to acquire deeper knowledge by accessing the private library of a wealthy businessman who opened its doors to workers on Saturday afternoons.

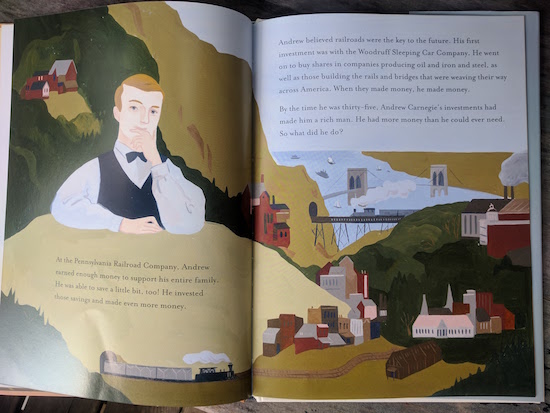

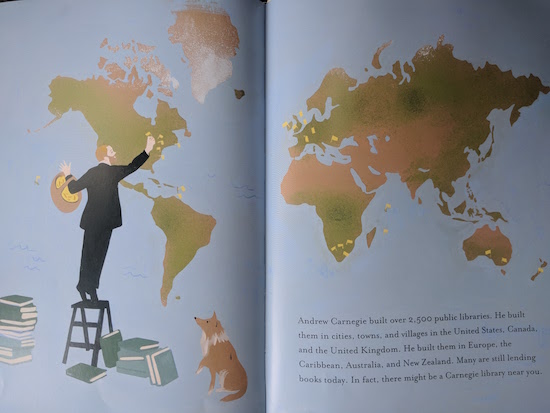

When Carnegie was 17, he got a job as a telegraph operator with the Pennsylvania Railroad Company, and by age 25 he was working in management. He started to make money, and invest money so that he made even more money. “By the time he was thirty-five, Andrew Carnegie’s investments had made him a rich man. He had more money than he could ever need. So what did he do?” Remembering the literary riches that had been shared with him in his youth, Carnegie worked to open public libraries so other working people could access books and learning. Carnegie’s first library was built in the Scottish village where he was born, and he would eventually build 2500 around the world.

Carnegie’s legacy is a mixed one, as a note at the back of the book makes clear. He fought against unions and resisted his employees’ efforts to fight for better working conditions and wages. As with everything, it’s complicated. But still, The Man Who Loved Libraries will provoke interesting conversations and make young readers reconsider ideas they might previously have taken for granted. At this moment in Western democracy, we need to underline the value of public libraries more than ever.

September 27, 2017

Niceness, kindness and goodness

I loved writing my essay, “Why we need to stop teaching girls to be nice” for Todays Parent because it was such an exercise in figuring out what I was thinking about. (If only all life’s dilemmas came with built in editors to underline parts of your understanding that are vague or ill-formed.) I got to think about goodness and kindness, and my discomfort with too much of an emphasis on empathy and that my daughters should feel that their responsibility is other people’s comfort. But also my puzzling out that teaching my daughters to care for themselves and take care of others is not necessarily incongruous. Even better, I get to reference So I Married an Ax Murderer, AND Joan Didion. I hope you will appreciate what I came up with. Thanks for reading!

September 26, 2017

My Body Might Know What My Head Don’t

Two weeks ago I did a talk at the Brockton Writers Series about my journey from blog to book, which was a journey that never would have gone anywhere had I tried to plot it. The thing with blogs, with books, with everything, I explained, is that you have to understand that you’re not necessarily in charge, and instead you need faith enough to follow the words where they lead you. And as I was giving my talk on that Wednesday night, I could hear my voice wavering just the littlest bit—”Interesting,” I thought to myself. “I must be nervous. Who knew?” Certainly not me, because I’ve come to take for granted that I am comfortable speaking to groups and I’d arrived prepared for my presentation. If not for the nearly inaudible wobble in my voice, I might never have known what I was feeling.

And isn’t that weird? How much about ourselves and our inner workings, emotional and otherwise, it’s really hard to be in touch with? Even though I’m a person who thinks all the time, can’t have a feeling without expressing it (god help the poor person who runs into me on the street when I’m the least bit upset about anything) and checks in emotionally with social media status updates multiple times a day. And I’m not being flippant about that last point—I don’t think status updates are necessarily as superficial as they’re made out to be. Sometimes Instagram is my way of taking stock of where I’m at for my own benefit. #TodaysTeacup is not just about the mug.

Anyway, yesterday this little burst of self-awareness proved insightful as I was trying to diagnose exactly what nonsense was going on in my brain. For a day or so, I’d been unable to shake this feeling that everybody hated me and thought I was stupid. Which is not to say that some people don’t hate me and think that I am stupid, some for very acceptable reasons, but just that my baseline for this portion of the population had rocketed skyward and I felt like a total loser. I felt conspicuous, vulnerable, and ridiculously sensitive…and there was something very familiar about it. I’d felt this way for a few weeks after my novel came out, a time that should have been amazing and euphoric but was so much more complicated than that and led to an entire Saturday that I spent lying on the floor.

The tide turned after that, by the way, one evening when I had an event and drank far too much wine beforehand, and refrained from saying anything entirely inappropriate in front of the group but still managed to have more fun than I’d been able to have in ages. And I’ve been having fun with my book ever since then.

But then all of a sudden there I was on Sunday feeling terrible again, when I should have felt terrific, after a chance to read from my book at the incredible Word on the Street Festival, and then an afternoon buying books and listening to authors and meeting up with bookish people, and having a very nice time. But then I would come away from every social interaction thinking, “Oh my god, I am a total knobhead. Why did I say that thing? Is working from home destroying me socially, so that whenever I go out in public I turn into a giant ninny? I wrote a book that everyone thinks is stupid. And how old do I have to be before I learn not to be socially awkward?”

It’s not that I am NOT socially awkward, like how there really are plenty of people who legitimately can’t stand me, but just that anxiety about all these things can ramp up to a level that’s actually debilitating. And that’s the real problem. And I was trying to figure this all out, why I was feeling the way I was feeling, or just what it was that I was feeling, because I didn’t have a clue. My voice was even pretty steady. But then it occurred to me that I’d spent the last three weeks with a higher profile than usual, with events and publications, and that possibly all the visibility had got to me. Same as when the book came out—so much was riding on what other people thought of me, their perceptions and judgements. For a while you can take it in stride. Like how when my piece about renting was so widely shared the other week, and it didn’t bother me. Everything was fine…and then all of a sudden it wasn’t anymore. And consciously I didn’t even know this was the case.

It is sort of ironic then to respond to my discomfort with visibility by writing it all down in a blog post, but a) nobody reads blogs anyway (except you of course, and I am so glad you do…) and b) my blog is how I make sense of everything. And while I don’t know exactly what the answer is to feeling too visible, except maybe to rent a burrow and the fortunate fact that I don’t have any events for the next few weeks, even just figuring it out makes me feel a lot better. The problem is not that everyone hates me and that I totally suck, but instead something has coloured my perception to make me think that this is the case. Which seems like a less daunting problem to grapple with. Suddenly, I hardly have a problem at all.

Update: I want to share a link to Billie Livingston’s essay, “How a White Trash Girl Stumbled on Grace”, which is not entirely irrelevant to any of this and is simply one of the most beautiful things that I’ve ever read. Or maybe it just arrived when I needed it most. Regardless, I am grateful.

September 25, 2017

Once More With Feeling, by Méira Cook

“This novel was not what I was expecting,” I wrote in my review of Méira Cook’s debut novel, The House on Sugarbush Road, in 2013, and it makes me laugh to see that now, because it’s exactly what I was going to say about her latest novel, Once More With Feeling. Possibly the only thing a reader can do with a Méira Cook novel is have no expectations at all. Because if you do, she’ll only grab you by them, and then swing you around and around her shoulder like a cowboy with a lasso. Or at least this was my experience of Once More With Feeling, which I’d been led to believe via the cover copy would be sweet and heartwarming, doddering professor Max Binder delivering an ill-advised gift to his wife on her birthday, the wife he’s still besotted with. I’d been setting myself up for a sweet comedy, a little bit homey and twee. But then the car drove off the road… Metaphorically and otherwise, and here we were barrelling down the off-roads, narratively speaking.

“This novel was not what I was expecting,” I wrote in my review of Méira Cook’s debut novel, The House on Sugarbush Road, in 2013, and it makes me laugh to see that now, because it’s exactly what I was going to say about her latest novel, Once More With Feeling. Possibly the only thing a reader can do with a Méira Cook novel is have no expectations at all. Because if you do, she’ll only grab you by them, and then swing you around and around her shoulder like a cowboy with a lasso. Or at least this was my experience of Once More With Feeling, which I’d been led to believe via the cover copy would be sweet and heartwarming, doddering professor Max Binder delivering an ill-advised gift to his wife on her birthday, the wife he’s still besotted with. I’d been setting myself up for a sweet comedy, a little bit homey and twee. But then the car drove off the road… Metaphorically and otherwise, and here we were barrelling down the off-roads, narratively speaking.

Once More With Feeling is not an easy book. (I think I said this about The House on Sugarbush Road as well.) It won’t be to everyone’s taste and there are things about it that are troubling, and I would have appreciated the end coming just a bit sooner than it did. I started reading this book on a plane, and to be completely honest there were a couple of points early on where I might have put the book down, had I not been thousands of feet in the air without another book to read. Not a singing endorsement, I know, but bear with me. I kept going, and it was not long after that it became clear to be that there was actually no better book for a four hour flight, or no situation better than a flight to enjoy a book like this. To give it the sustained attention it requires, and to have my reading time so richly filled with so many voices and stories. It’s hard to appreciate a feast in tiny bites, is what I mean, and so it was nice to just keep my seatbelt on and read voraciously.

Once More With Feeling is a novel about a city, Winnipeg in four seasons, although Winnipeg isn’t named. It’s specified though, and it reminded me of my favourite Winnipeg novel, Carol Shields’ The Republic of Love, in how the city is evoked, the sweep of its year. The two books are complementary, though Once More With Feeling is darker, with an edge. And every chapter is from a different perspective, connections between some of the characters tangential, and we get to see some of them from their internal monologues and also from far away. There is startling ambition as to the range of characters how share the story’s helm, a relay passed from one to another. Literature Professor Max Binder, then his wife’s editor at the local newspaper (whose contents we glimpse via letters from outraged readers). The newspaper’s spinster bookkeeper (who has a secret life of her own, surely) volunteers at a local mission that serves food to the homeless, and so the next chapter is from the perspective of another volunteer, whose mother is the Binder’s cleaner and whose sister is just one of many women who’ve gone missing on the city’s streets. And onward, through Max Binder’s children, and their schoolmates.

My favourite chapter was “Inspirational Living Centre,” from the perspective of a wayward high school student whose class gets paired up with Holocaust survivors. And while the bubbly popular girls in the class embrace this experience (“On the way back from the Inspirational Living Centre some of the girls said theirs were “cute” and Courtney Segal even said hers was “adorable.”) But the narrator is matched with a curmudgeonly asshole who refuses to be inspirational, and even ticks off Courtney Segal on the bus ride home—”Why can’t you keep your Holocaust survivor from bothering ours?” she demands.

Teenagers at the mall, a camp director in September, a chorus of Jewish mothers reflecting on Bar and Bat Mitzvahs past in a chapter that reminded me of Grace Paley (in which time made a monkey of us all). A chapter from the perspective of Lazer Binder’s English teacher’s ex-hushand, the Binders’ next door neighbour, two elderly sisters, and then back to Maggie after a year of grief and rage and the arrival of the missing piece of the puzzle of what ultimately happened to Max. And what is the plot? Which is the same question as what propels the story? Well, the sweep of days and months and change of the seasons, of course, the furious momentum of life itself, in a city in particular where nothing sits still for a moment.

Although with a Méira Cook novel (and this is her third) the language is as important as the plot is, and the vocabulary of this one is rich and dextrous. Cook is an extraordinary writer, an award-winning poet, as adept at plotting words as story—her sentences are truly magnificent.

September 22, 2017

Mr. Crum’s Potato Predicament, by Anne Renaud and Felicita Sala

I was going to say that chips are my weakness, but I prefer Stephanie Domet’s term, that they’re her “kryptonite.” Domet is the inventor of the #stormchips hashtag, a Martime phenomenon in which an impending storm necessitates the procurement of snack food, chips mainly. Last winter in our household I tried to make #stormchips into a thing, keeping a bag on hand in case of blizzard, except we don’t have the right kind of climate and I just ended up eating chips without a storm. Who needs a storm? Not me, which is why I can’t buy chips, but I love them. One after another, crispy, salty, greasy, kettle-baked, and preferably flavoured with salt and vinegar.

I had a bag of chips last weekend, Old Dutch Chips, because I was in Edmonton and they’re a western thing. I ate them on my flight home and they were so good my eyes actually rolled back into my head, and the thing about something this amazing is the remarkable fact that you can just have them. That there are chips in the world at all, I mean, readily available at any moment to be eaten, usually in giant handfuls. I am incapable of eating potato chips without stuffing them into my mouth like a madwoman, a chip-monster. I have never been able to eat just one chip or a couple. This is my problem. I’m not terribly bothered by it.

For all my talk of can’t buy chips and won’t buy chips, I buy a lot of chips, or at least lately. We eat chips when we’re camping or when we’re at the cottage, and there was a moment this summer when I was actually a bit tired of chips. Which it had never remotely occurred to me was possible. But last weekend’s chips were special occasion, chips outside of season. Although that I was on an airplane at the time kind of negates the whole occasion; I was in transit and one could argue it never really happened at all. The Old Dutch thing was really on my mind because I’ve got the new book Snacks: A Canadian Food History on deck, which I’m planning to read in the company of a bag of Hawkins Cheezies, and probably some chips. And I don’t think it’s weird to plan your reading material around their snacking opportunities. Because if there’s one thing I know, it’s that you can’t eat chips without occasion.

Fortunately, there is one more literary occasion for opening up a bag of chips, and that’s the picture book Mr. Crum’s Potato Predicament, by Anne Renaud and Felicita Sala, and it will make you hungry. (It also reminded me of Kyo Maclear and Julie Morstad’s Julia, Child in all the best possible ways.)

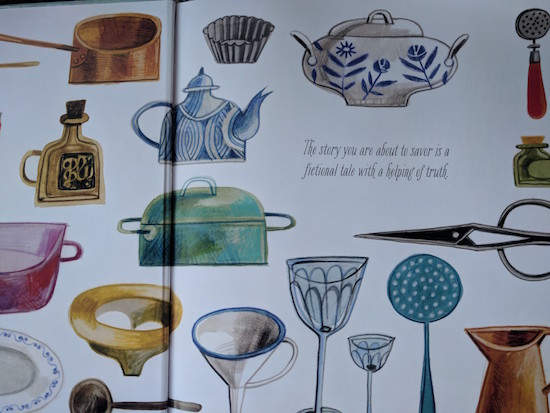

“The story you are about to savour is a fictional tale with a helping of truth,” the book begins, and then the reader is introduced to George Crum, his waitress Gladys, and the persnickety customer in George’s restaurant whose pickiness would lead to the advent of potato chips, as George is encouraged to cut his fried potatoes into thinner and thinner slices in order to satisfy his customer’s particular demands. The story is playful and light hearted, with a fantastic vocabulary, rich with synonyms and adjectives and gorgeous euphony. Crum was a real figure, Renaud’s author’s note informs us, though he is but one of many people credited with invented chips with his thin potatoes. But Crum certainly did play a role in making chips famous, and both author and illustrator have a lot of delicious fun bringing this historical character to life.

September 21, 2017

The Mother, by Yvvette Edwards

Last week I read The Mother, by Yvvette Edwards, a really beautiful and harrowing story of a mother attending the trial of the boy whose been accused of murdering her teenage son. Written in the first person in a voice that is raw and sometimes faltering, it’s not an easy read emotionally, but the novel is also fast paced and gripping. It evokes interesting question about motherhood, race, class and the ways in which we all assume our families, our children, can be inoculated against the social problems outside our warm and and cozy homes. The ways in which we assume too that we can exist apart from the world and its violence, and that there are issues we can say with certainty, “That is not my problem.”

It’s a deeply thoughtful and warmly provocative novel, Edwards’ second after A Cupboard Full of Clothes, which was long listed for the Man Booker Prize and shortlisted for the Commonwealth Prize. I learned of this title after reading Donna Bailey Nurse’s interview with Edwards, which you can read here—and I am so glad I did.

From Donna Bailey Nurse: “I admire Edwards’s authentic portrayal of Caribbean men and women. She is particularly adept at capturing the lithe movements of a certain kind of West Indian male. I was not surprised to learn that Toni Morrison is her “star” author or that she counts Beloved among her most cherished novels. As in Beloved, Edwards works with the opposing forces of murder and motherhood. And like Morrison, the psychological action of her fiction unfolds largely within the realm of black people. In The Mother Edwards describes the harsh circumstances and complex dynamics of an embattled community. At the same time she conveys the sense of a black British family rooted firmly in love.”