January 24, 2018

That Random Person on Twitter Isn’t Stalin

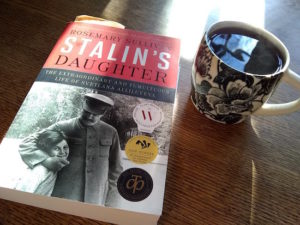

I honestly don’t think about Stalin very often. I read Rosemary Sullivan’s biography of Svetlana Alliluyeva last month and it was actually revelatory to be reminded that Stalin actually happened, that the story wasn’t inevitable, and to glimpse the awfulness of living within that terrible present which would unfold into the brutal and murderous history. When Svetlana moved to America, the idea that she’d enrol her daughter in public school was reprehensible to her, and she had no truck with American socialists, the fellow travellers. Her response to living under Stalin and his successors was not exactly nuanced, or considered, I mean, but then I think that’s probably a lot of ask of anybody.

I honestly don’t think about Stalin very often. I read Rosemary Sullivan’s biography of Svetlana Alliluyeva last month and it was actually revelatory to be reminded that Stalin actually happened, that the story wasn’t inevitable, and to glimpse the awfulness of living within that terrible present which would unfold into the brutal and murderous history. When Svetlana moved to America, the idea that she’d enrol her daughter in public school was reprehensible to her, and she had no truck with American socialists, the fellow travellers. Her response to living under Stalin and his successors was not exactly nuanced, or considered, I mean, but then I think that’s probably a lot of ask of anybody.

Still, I don’t think about Stalin very often, but last week I started to think maybe I was alone in this. This was the week that Margaret Atwood published an op-ed defending her feminist credentials, and reiterated that a lack of dude process regarding sexual assault cases was analogous to Stalinist purges, and then someone else on Facebook got upset because a small press declared a poet’s books out of print (after his public announcement that he’d only got them published because he knew the right people to have drinks with) because this was apparently Stalinist-era censorship, and just yesterday a couple of men on Twitter were comparing poets on Twitter to the East German secret police, which wasn’t referencing Stalin exactly, but it’s all in the spirit of the thing.

It turns out that a lot of people are thinking about Stalin all the time. And they see him everywhere they look, on Twitter threads, and Facebook conversations, in the back of the closet, and under the bed, but never, oddly enough, in the mirror. And while one might say that my lack of engaged consideration about Stalin on a regular basis may be to my detriment, because those who don’t know history are condemned to repeat it, I’m not convinced. Because while I don’t think about Stalin very often, I think about him enough to realize that random person on Twitter yelling at Margaret Atwood is not him. And neither are women circulating a shitty men list, or calling out sexual predators by name, or Indigenous people who have thoughts and ideas to express about cultural appropriation. Even if those people are angry. That woman who runs a small press? Not Stalin. That person who is attacking the thing you said, or the story you wrote, or the tweet you tweeted? Not Stalin. In particular if that person is trans, or disabled, or a person of colour (and yes, I know Stalin was also a minority, being Georgian, but that’s not the same thing), because what Stalin had was power to oppress people with, and the people you’re accusing of being Stalin? They don’t have much power at all.

That annoying woman on Twitter whose feed is full of weird politically correct jargon that is very irritating to read is not Stalin. That strange person with blue hair whose preferred pronoun is an unpronounceable word you’ve never heard of is not Stalin. That very earnest person who’s currently going around Twitter calling out anyone with the nerve to be reading Margaret Atwood right now is not Stalin. She’s kind of an idiot, but that’s not the same as being Stalin, and I think a lot of people are having a lot of trouble telling the two things apart. Even the person who’s going to be upset for me for making fun of people with blue hair and weird pronouns two sentences back is not Stalin…unless that person happens to have the power to throw me into prison for an indefinite period of time.

It’s not that I’m trying to minimize the crimes and atrocities of Stalin and his tyranny, in fact I’m doing quite the opposite. It’s because I know that Stalin is possible—and that power can make a person so dangerous—that making distinctions between the man himself and annoying people on Twitter is really important. Making the distinction is also important, because it seems like Stalin-hysteria is a reflexive response to moments in which people who’ve been oppressed are seeking to redress a power imbalance, when one might be feeling as vulnerable as a Romanov in 1917. Except that it’s 2018, and you’re talking about somebody on Twitter with 278 followers, and you’ve decided that your possibly legitimate fear of the USSR happening all over again means that, as a matter of principle even, you don’t have to listen to what other people have to say.

This morning I was delighted with Erika Thorkelson’s essay, “Margaret Atwood’s Books Taught Me To Listen to Women,” and not just because—most refreshingly—she doesn’t mention Stalin or the Gulag even once. It’s a beautiful piece about the importance of listening, which, Thorkelson writes, “requires full body presence. It requires you to soften and let go of the fear, the urge to argue, and the instinct to control the narrative. It takes a comfort with silence and a willingness to accept that your turn to talk may never come, that what’s happening might not be about you at all.”

What’s happening might not be about you at all. What a thing! It might not even be about Stalin…

Thorkelson continues, “The greatest block to really listening is not the noise of the world, but that voice inside that protects us, centers us, rattles with outrage or disbelief.” The voices that tells us that Stalin is hiding under the bed, and that you alone are the last bastion against evil and tyranny, when, in your refusal to listen, it might be tyranny (and/or the shoddy status quo) that you are, in fact, upholding.

January 23, 2018

Winter, by Ali Smith

I walked through a blizzard to buy Winter a week and a half ago, the new release by Ali Smith that I’ve been looking forward to since rereading Autumn in the autumn. A novel that helped me so much through the political turbulence that was 2017, contemporary events as rendered by literature so that they were just enough at a distance–it was clarifying, and gave me hope. And so it was strange to pick up Winter, the second book in Smith’s seasons sequence, and see that everything wasn’t okay after all. That one book is not going to cure us of what ails us, and the trouble continues through winter, a season during which nature settles down to sleep:

I walked through a blizzard to buy Winter a week and a half ago, the new release by Ali Smith that I’ve been looking forward to since rereading Autumn in the autumn. A novel that helped me so much through the political turbulence that was 2017, contemporary events as rendered by literature so that they were just enough at a distance–it was clarifying, and gave me hope. And so it was strange to pick up Winter, the second book in Smith’s seasons sequence, and see that everything wasn’t okay after all. That one book is not going to cure us of what ails us, and the trouble continues through winter, a season during which nature settles down to sleep:

“God was dead: to begin with. / And romance was dead. Chivalry was dead. Poetry, the novel, painting, they were all dead, and art was dead. Theatre and cinema were both dead. Literature was dead. The book was dead. Modernism, postmodernism, realism, and surrealism were all dead…”

The novel opens the day before Christmas, with Sophia Cleves who is haunted by a disembodied head. Interestingly, this being an Ali Smith book where surrealism is so often present, it doesn’t occur to me until later when we see Sophia through the eyes of other characters, that there is anything unusual about a woman being haunted by a disembodied head. Autumn had the weirdness of people turning into trees, and the head spectre is the strangeness of Winter, and usually these are points that would make me want to give up, but so much else makes me go on. Autumn opens with the absurdity of a character’s engagement with a bureaucrat at the passport office, and Winter does a similar trick with Sophia Cleves’ visit to the bank before they close at noon on Christmas Eve—the insanity and banality of these kind of engagements with the state and/or corporation, the robotic interaction between a human being and a person who’s just doing their job—presumably a human being as well.

Sophia Cleves is not the centre of Winter (the dead of?), which is instead her son Arthur, Art. Who writes a blog called Art in Nature, about stepping in puddles and bird sightings. Art who I was all prepared to sympathize with, all set for him to be my hero—and then we realize that as a hero he’s terribly flawed. His furious girlfriend berating him for his lack of engagement with the world around him, for believing he’s doing his part through his blog posts (which are totally made up; Art never leaves the city), and not seeing what’s going on around them. He tells her, “We’re all right… Stop worrying. We’ve enough money, we’ve both got good assured jobs. We’re okay.”

“Forty years of political selfishness…” she continues. Political divides, the rise of fascism, plastic bags, etc. And he dismisses her, all of it. It’s the way it always been, he tells here. These things are cyclic. Whatever, whatever. We’ll be all right. It’s all fine.

I am Art. This revelation occurred to me around page 58. This, and the fact that I’m a climate change denier , which is a revelation I had on Friday when I got in an argument with my dad about why we see robins around in the winter. “It’s totally normal,” I say, because I read it somewhere once. “Climate change,” says my dad. “It’s getting warmer, it’s scary.” And I become a bit hysterical. I don’t want to be scared. I know climate change is real, but I’m not sure what I’m supposed to do about it in my tiny little life, and so to preserve my sanity I cling to signs that everything is normal. For example, about how when I bought this book, I walked through a snowstorm. A blizzard. In the winter. Things are fine.

The story takes place over Christmas at Sophia’s, when Art comes to stay with his girlfriend, who is not his girlfriend (who has just broken up with him due to his political selfishness) but instead a random woman he meets on the street, an immigrant from Croatia via Toronto with a penchant for Shakespeare who is struggling to get by. When they arrive, it becomes clear that Sophia is not okay, and so they call her estranged sister Iris to come and help, Iris the old hippie, who’d protested against nuclear weapons at Greenham Common, Iris who is the living embodiment of another way to face the world, a way that’s different from Sophia and Arthur’s denial—of seeing, of engaging, and doing her part to change the world. Insisting that, via Greenham Common, she really did.

But it’s not as simple as that, of one way being the good way to live, and the other being bad. There is a moment when Iris and Sophia say to each other, “I hate you.” “I hate you.” And then embrace, and lay down together in bed, and there it is, what has to happen. It isn’t easy. It isn’t neat. But somehow these characters, “see its the same play they’re all in, the same world, that they’re all part of the same story.”

That last line a reference to Shakespeare’s Cymbeline (which I’ve never read or seen!), the play that makes Arthur’s not-girlfriend come to England, in fact. “A play about a kingdom subsumed in chaos, lies, powermongering, division and a great deal of poisoning and self-poisoning”…. “I read it and I thought, if this writer from this place can make this mad and bitter mess into this graceful thing it is in the end where the balance comes back and all the lies are revealed and all the losses are compensated, and that’s the place on earth he comes from, that’s the place that made him, then that’s the place where I’m going.”

Art is how we get there, is Smith’s thesis in this novel. Through Shakespeare, yes, but also by seeing what happens when we put real things in fiction—things like Brexit, and the Grenfell Tower fire. What happens to books when we put the world in it is a question that’s addressed in the most wonderful way, Arthur’s not-girlfriend (whose name is Lux) telling the story of an old copy of Shakespeare kept in a library with the imprint of what was once a flower pressed between the pages. “The mark left of the page by what was once the bud of a rose.” She’d called it, “the most beautiful thing I have ever seen… it was a real thing, a thing from the real world.”

Which was exactly what had made Autumn so powerful to me, and otherworldly too in the ways in which it did engage with the world. It was why reading it again in October was such a big deal, to be present in the novel’s moment. It was why it was especially meaningful to keep reading and discover that the Shakespeare play Lux refers to is housed at the Fisher Library here in Toronto, right at the end of my street. Uncanny, isn’t it? The line between life and fiction blurred in the most fascinating fashion.

My favourite thing about Winter was everything, but I especially loved its connections to Autumn, which are lovely, subtle, and so unbelievably perfect. Except I read somewhere that Spring’s not out until 2020, and how am I supposed to wait that long?

January 22, 2018

The Opposite of Democracy

“…the ideal of the internet represents the very opposite of democracy, which is a method for resolving difference in a relatively orderly manner through the mediation of unavoidable civil associations. Yet there can be no notion of resolving differences in a world where each person is entitled to get exactly what he or she wants. Here all needs and desires are equally valid and equally powerful. I’ll get mine and you’ll get yours; there is no need for compromise and discussion. I don’t have to tolerate you and you don’t have to tolerate me. No need to care for my neighbour next door when I can stay with my chosen neighbours in the ether, my email friends and the visitors to the sites I visit, people who think as I do, who want what I want. No need for messy debate and the whole rigamarole of government with all its creaky bothersome structures. There’s no need for any of this, because now that we have the World Wide Web the problem of our pursuit of happiness has been solved! We’ll each click for our individual joys, and our only dispute may come if something doesn’t get delivered on time. Would you rather be at home?”

“…the ideal of the internet represents the very opposite of democracy, which is a method for resolving difference in a relatively orderly manner through the mediation of unavoidable civil associations. Yet there can be no notion of resolving differences in a world where each person is entitled to get exactly what he or she wants. Here all needs and desires are equally valid and equally powerful. I’ll get mine and you’ll get yours; there is no need for compromise and discussion. I don’t have to tolerate you and you don’t have to tolerate me. No need to care for my neighbour next door when I can stay with my chosen neighbours in the ether, my email friends and the visitors to the sites I visit, people who think as I do, who want what I want. No need for messy debate and the whole rigamarole of government with all its creaky bothersome structures. There’s no need for any of this, because now that we have the World Wide Web the problem of our pursuit of happiness has been solved! We’ll each click for our individual joys, and our only dispute may come if something doesn’t get delivered on time. Would you rather be at home?”

—Ellen Ullman, “The Museum of Me,” which WAS WRITTEN IN 1998 (!!), from her amazing essay collection Life in Code.

January 17, 2018

There Will Be Blood

So the post I was going to write last week, before I got all riled up and furious, was a story about flossing, and also about Fargo, the perils of watching too much TV, and how excellent it is that I finally (after a decade) discovered a television show I like as much as Mad Men. And I will situate the beginning of this story about fifteen years ago when I had this fervent belief that flossing was unnatural and even harmful. “I’ve just got an aversion to anything that makes me bleed,” was the way I used to put it, but then I got health benefits, in addition to a lot of cavities, and started a serious relationship with my dental hygienist (seeing her at least once every six months) and now I find I’m putting my money in the pockets of Big Floss on a regular basis.

So the post I was going to write last week, before I got all riled up and furious, was a story about flossing, and also about Fargo, the perils of watching too much TV, and how excellent it is that I finally (after a decade) discovered a television show I like as much as Mad Men. And I will situate the beginning of this story about fifteen years ago when I had this fervent belief that flossing was unnatural and even harmful. “I’ve just got an aversion to anything that makes me bleed,” was the way I used to put it, but then I got health benefits, in addition to a lot of cavities, and started a serious relationship with my dental hygienist (seeing her at least once every six months) and now I find I’m putting my money in the pockets of Big Floss on a regular basis.

Basically, this is a story about life in my thirties and the wild incredible risks I take in my every day life. And about how I started watching Fargo in November was immediately infatuated, its characters living large in my mind after each episode ended. I was thinking about Molly Solverson all the time, and how both seasons one and two are partly about being a woman in a man’s world and negotiating with reality on those terms. And also how, like Mad Men, Fargo is a show that throws out the conventions of storytelling, skipping large blocks of time, having important details like weddings happen off-scene. And what I loved best about Fargo was how it doesn’t manipulate its viewers, how we usually know what the outcomes are going to be—who survives and who doesn’t, will they fall in love or won’t they—so that the details that keep us riveted are not those you’d usually expect, that it’s a different kind of tension. Not the what, but how. And how the writers have to come up with different ways to surprise us, hold us, than the usual twists of narrative.

I was also intrigued by the show’s questions and considerations of morality and character, and good and evil, which recalled Mad Men in their complexity, nuance and lack of a clear answer (which is why its all so interesting). The presence of a moral centre made the exploration of evil and villainy so much more palatable and the violence less troubling than it might have been. Mad Men was much less fixed that way—everyone was always selling out someone. (And now I’m thinking about the scene with the tractor in “Guy Walks Into an Advertising Agency,” and in its gory absurdity it was absolutely Fargo-esque.)

Usually I just watch TV one or two nights a week, because I tend to spend most of my evenings reading, but because the holidays are not for moderation, we got to watch Fargo every day. Which had a downside, because I started talking with the accent and saying, “You betcha” and became more than a little bit obsessed—our children had to ask us to stop talking about Fargo because our behaviour was not just alienating, it was boring. We finished up Season 1 in the week before Christmas, and went straight into Season 2, which was so different but I came to love just as much, although it was Season 1 that hit me hardest. The season finale was so full of tension I could hardly stand it, and kept having to leave the room and get away from the waiting for something to happen (which was never going to be the thing you saw coming after all…).

Usually I just watch TV one or two nights a week, because I tend to spend most of my evenings reading, but because the holidays are not for moderation, we got to watch Fargo every day. Which had a downside, because I started talking with the accent and saying, “You betcha” and became more than a little bit obsessed—our children had to ask us to stop talking about Fargo because our behaviour was not just alienating, it was boring. We finished up Season 1 in the week before Christmas, and went straight into Season 2, which was so different but I came to love just as much, although it was Season 1 that hit me hardest. The season finale was so full of tension I could hardly stand it, and kept having to leave the room and get away from the waiting for something to happen (which was never going to be the thing you saw coming after all…).

I’d left the room to get dental floss, because not only have I sold out to the dentist, but also because one of the great pleasures of my every day these days is the experience of going to bed. But I couldn’t stay away too long, not wanting to miss whatever happened next in the show, as much as I couldn’t stand to wait for it. So I came back, floss in hand, and perched delicately on the arm of the sofa, watching the screen over my husband’s shoulder. Dental floss wrapped around my two index fingers, so that my hands were essentially bound, and the floss and my fingers doing their work in my mouth so that I was basically gagged as well—a vulnerable position if ever I saw one, but at least I wasn’t dressed in just my underwear and running away across a barren Minnesota plain in the dead of winter. A season of Fargo had made clear that certainly things could be much worse.

But then I fell off the couch. In a few seconds that stretched out into an eternity in my mind, and I could see it all happening as it did. “This is completely ridiculous,” I thought, as I teetered on the edge, unable to call out to my husband to steady me, unable to reach out for support. Bound and gagged, I plummeted to the floor, landing with a crash that must have disturbed the downstairs neighbours. Free-falling is less romantic than it sounds, and nobody ever writes songs about the landing. It’s been nearly a month, and my wrist and elbow have been aching ever since.

But I continue to be cavity-free.

January 16, 2018

New Mitzi Bytes things…

Photo Credit: Julie at Try Small Things

I was delighted a few weeks back to discover that Mitzi Bytes was the January pick for the Sweet Reads Box, which is a very cool curated subscription box that includes one book and assortment of other fun things associated with the book’s story and theme. And as the boxes have been delivered this week, I’ve enjoyed (along with their recipients!) discovering what items are accompanying the book, especially because they’re so thoughtful and perfect and include my very favourite flavour of tea (which is my character’s favourite flavour of tea too, a detail I’d forgotten). To see what I’m talking about, head over to Try Small Things to see the Mitzi box unpacked, and to enter for a chance to win the January box for yourself. I’ve read the book already, in fact I wrote it, but I’m still a little disappointed that I didn’t order one before they sold out. The giveaway is featured in a few other places too if you search with the #SweetReadsBox hashtag on Instagram. I’m so thrilled to see my book finding readers in such a delightful way!

I’m also very happy to read such a smart and insightful take on Mitzi Bytes by Donna Bailey Nurse, a reader and writer I really admire, and who was kind enough to talk to me about my writing and life in an excellent conversation a little while back—you can read her article here. I’m always appreciative of readers who are able to discern that Mitzi Bytes’ lightness is deceptive and there’s a lot more going on under the surface.

And finally, I am happy to be featured on BoldFace, the blog at Editors Toronto, where I talk about the work I do, my discomfort with identifying as an editor, and also get to give props to the editors I’ve been so fortunate to work with so far in my career. You can read it here.

January 15, 2018

“The umbrella exists in a state of flux…”

“Nowadays, in a time when most umbrellas aren’t worth the stealing and are tossed aside like sweet wrappers when they fail, umbrella theft and ‘frightful moralities’ have been largely replaced by general indifference. Like pens, plectrums [guitar pick: who knew?], and Tupperware containers, the umbrella often seems an entity that is not owned but exists in a state of flux, travelling from person to person, taken up and left behind according to various states (or absences) of mind. Think of umbrellas doing endless loops on the Circle line, the inevitable bundles in the corner of lost property offices, the umbrellas in the staff room that nobody seems to own, or forgetting which they do own, they are afraid to take one away lest it actually belong to someone else. I would suggest that modern-day umbrella ownership has less to do with a specific object than the category as a whole: one possesses an umbrella, not their umbrella.” -Marion Rankine, Brolliology: A History of the Umbrella in Life and Literature.

“Nowadays, in a time when most umbrellas aren’t worth the stealing and are tossed aside like sweet wrappers when they fail, umbrella theft and ‘frightful moralities’ have been largely replaced by general indifference. Like pens, plectrums [guitar pick: who knew?], and Tupperware containers, the umbrella often seems an entity that is not owned but exists in a state of flux, travelling from person to person, taken up and left behind according to various states (or absences) of mind. Think of umbrellas doing endless loops on the Circle line, the inevitable bundles in the corner of lost property offices, the umbrellas in the staff room that nobody seems to own, or forgetting which they do own, they are afraid to take one away lest it actually belong to someone else. I would suggest that modern-day umbrella ownership has less to do with a specific object than the category as a whole: one possesses an umbrella, not their umbrella.” -Marion Rankine, Brolliology: A History of the Umbrella in Life and Literature.

January 10, 2018

“Be as large as you’d like to be.”

I was all set to write a blog post about how I hurt my elbow on the Christmas holidays because I fell off the couch when I was bound and gagged (this actually happened) but you’re going to have to wait until next week now for that story because I’ve got something on my mind. I was thinking about the fallout from what’s happening regarding Concordia University’s English Department (short version: a man articulated something women have been talking about for years regarding predatory males on the faculty, and then yesterday it was the six o’ clock news), all these conversations about men in positions of power—and then it occurred to me, “What is this ‘power’ we’re talking about?” The power of a part-time job teaching creative writing? The power of a handful of slim books of poetry whose sales total into the hundreds? The power of editing a literary magazine that nobody ever reads unless they’d like to be published by them (which would then permit said reader/writer the power of a publication credit)? If this is what passes for “power,” then we’re sadly impotent, the lot of us.

I was all set to write a blog post about how I hurt my elbow on the Christmas holidays because I fell off the couch when I was bound and gagged (this actually happened) but you’re going to have to wait until next week now for that story because I’ve got something on my mind. I was thinking about the fallout from what’s happening regarding Concordia University’s English Department (short version: a man articulated something women have been talking about for years regarding predatory males on the faculty, and then yesterday it was the six o’ clock news), all these conversations about men in positions of power—and then it occurred to me, “What is this ‘power’ we’re talking about?” The power of a part-time job teaching creative writing? The power of a handful of slim books of poetry whose sales total into the hundreds? The power of editing a literary magazine that nobody ever reads unless they’d like to be published by them (which would then permit said reader/writer the power of a publication credit)? If this is what passes for “power,” then we’re sadly impotent, the lot of us.

Of course, there is power. As a reader and a writer and someone who published a small press book and continues to be grateful to publish in literary journals, I know that there is indeed power in words, poems and stories; that lit mags can be magic; that small independent presses can move mountains; and a slim book that sells a few hundred copies might matter so much. I do not seek to undermine these institutions, systems and networks. I feel fortunate to have benefitted from them, but I also know that their power is in the works themselves, and that it’s a small and subtle thing, a power that can’t be quantified. This real power is also not a thing that can be lorded over others.

But I’m getting away from the point here, which is the ridiculous fact that a slovenly man with a part-time job and magazine imagines himself as having power. That we’re meant to looking up to a guy who churns out books that nobody reads and who is trapped in perpetual adolescence. That eventually that guy is in his fifties, and he’s entertaining the notion that a brilliant young woman might want to have sex with him—where, I would like to know, does a person get a sense of entitlement like that? Because, quite frankly, I would like to go there and get some too.

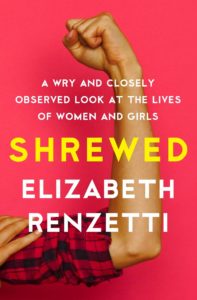

On Sunday I read an advanced copy (out in March) of Elizabeth Renzetti’s brilliant, generous, biting and moving collection of essays , Shrewed: A Wry and Closely Observed Look at the Lives of Women and Girls. I loved it. I wanted to read passages to my daughters, buy a copy for my mother, and plan to implore everyone I know to pick up a copy. Several essays had me in tears by the end, others made me want to grab a placard and march down the street, my shrill voice exclaiming, Feminist, feminist, feminist, feminist, feminist is for me! It’s a beautiful book rich with lessons learned from a few decades on the feminist frontline. And the theme that emerged as I read the essays was of not-enoughness—not enough women on the US Supreme Court, not enough women MPs in Canada’s House of Commons. (Related: why does nobody ever ask how many is enough men? Oh, wait! Me all the time. But never mind. Maybe a man will write a blog post about it and then we can hear about it tomorrow on the news.)

On Sunday I read an advanced copy (out in March) of Elizabeth Renzetti’s brilliant, generous, biting and moving collection of essays , Shrewed: A Wry and Closely Observed Look at the Lives of Women and Girls. I loved it. I wanted to read passages to my daughters, buy a copy for my mother, and plan to implore everyone I know to pick up a copy. Several essays had me in tears by the end, others made me want to grab a placard and march down the street, my shrill voice exclaiming, Feminist, feminist, feminist, feminist, feminist is for me! It’s a beautiful book rich with lessons learned from a few decades on the feminist frontline. And the theme that emerged as I read the essays was of not-enoughness—not enough women on the US Supreme Court, not enough women MPs in Canada’s House of Commons. (Related: why does nobody ever ask how many is enough men? Oh, wait! Me all the time. But never mind. Maybe a man will write a blog post about it and then we can hear about it tomorrow on the news.)

And of course, the book is very much about the way that women are made to feel as though they themselves are never enough—not smart enough, pretty enough, assertive enough, friendly enough, small enough, imposing enough, busty enough, thin enough, conforming enough, or original enough. As a woman, there are infinite ways to be faulty. Which is why it’s particularly powerful when Renzetti writes in her final piece, “Size Matters: A Commencement Address”: “Be large. Be as large as you’d like to be. Take up room that is yours. Spread into every crack and corner and wide plain of this magnificent world. Sit with your legs apart on the subway until a man is forced, politely, to ask you to slide over so he can have a seat. Get the dressing on the salad. Get two dressings. Order the ribs on a first date.”

(And then she goes on to write, “Throw away your scale. Stop weighing yourself. Is there ever a reason to know your precise weight? Are you mailing yourself to China? Are you a bag of cocaine?” Oh my gosh, this book…)

There are so many lessons that I’m taking away with this tragedy/debacle at Concordia/the world in general, but here’s the one I am focussing on today: if a slovenly largely unsuccessful middle aged writer can imagine himself a powerful sexual Lothario then it is possible I might actually be enough after all. Even more than. If a fucking imbecile can be President of the United States, there is really not limit for the rest of us sentient beings. If some guy who edits a literary journal is a powerful figure, then I am fucking King Kong with Godzilla riding on my shoulders, and so are you. And from now on we should be that large, and own the power we’re entitled to.

January 8, 2018

What I read on my holidays…

I think it happened the year I spent Christmas reading Hermione Lee’s biography of Penelope Fitzgerald, when the holidays began to seem to me like a fine vessel for reading biographies. With the time and space necessary to become absorbed by books so book and consuming, 500 or so pages most of them, which isn’t a number of pages that one can read in dribs and drabs. I’ve also developed a habit of going offline for a week or so at Christmas, which helps to get books like this done. Last year my Christmas biography project involved books about Claude Monet, Jane Jacobs, and Shirley Jackson, which was wonderful. So I was been looking forward to the holidays this year, stockpiling life stories, and it was a lot of pages, a lot of living, but I read four biographies in the end, biographies of four women who seem disparate at first glance, and there was such pleasure in drawing their stories together and understanding the ways in which their lives and experiences intersect.

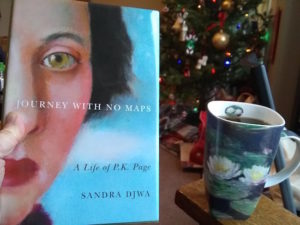

The book I read first was Sandra Djwa’s beautiful award-winning biography of P.K. Page, whose work I’m not very familiar with (although I met her once, in grad school. I can scarcely believe this actually happened. What did I say to her? Hopefully nothing…). Journey With No Maps is the book’s title, which would also be a fitting description for all women whose lives I read about during my holiday, and it was a gorgeously written evocative read. It follows Page through her life and experiences as a writer, a painter, and a diplomatic wife in Australia, Brazil and Mexico. What impressed me most with Page was the way in which she was just incredibly good at everything she set her mind to—she never really had an apprenticeship. Which is not to say that she didn’t grow and develop as an artist, but she was always P.K. Page. She seems to have always been excellent.

The book I read first was Sandra Djwa’s beautiful award-winning biography of P.K. Page, whose work I’m not very familiar with (although I met her once, in grad school. I can scarcely believe this actually happened. What did I say to her? Hopefully nothing…). Journey With No Maps is the book’s title, which would also be a fitting description for all women whose lives I read about during my holiday, and it was a gorgeously written evocative read. It follows Page through her life and experiences as a writer, a painter, and a diplomatic wife in Australia, Brazil and Mexico. What impressed me most with Page was the way in which she was just incredibly good at everything she set her mind to—she never really had an apprenticeship. Which is not to say that she didn’t grow and develop as an artist, but she was always P.K. Page. She seems to have always been excellent.

I wasn’t sure what the through lines would be from Page’s life to that of Svetlana Alliluyeva in Stalin’s Daughter, except that Rosemary Sullivan, who wrote the book, appears as a character in Journey With No Maps, which is very cool to consider. Svetlana’s story shows an extreme version of a pattern set out in Page’s biography, that of a woman being defined by her relationships to men. I suppose Svetlana’s is also a story of being in a family with a diplomat—she is paraded out during her father’s dinner with Churchill in 1942—even if the diplomat in question is Stalin. And there is unrequited love in both books—before her marriage, Page was deeply involved in a relationship with a married man that she never entirely got over; Svetlana, sadly, falls passionately in love with one man after another. We learn about Khrushchev’s Thaw, which brought with it political instability—Soviet tanks would crush a Hungarian uprising in 1956, at the same time that P.K. Page’s diplomat husband Arthur Irwin was working with Lester B. Pearson to ease tensions during the Suez Crisis. In 1967, Svetlana would defect to America. Also, Frank Lloyd Wright’s third wife is a bad bad woman, in that she brought Svetlana into an architectural cult and stole all her money. Seriously. The book was such a page-turner, Sullivan is such a wonderful biographer, and Svetlana Alliluyeva was a fascinating woman with literary talent and a fierce intelligence that was so often undermined. I found it interesting to learn how much she resisted all notions of socialism and communism after her experiences of totalitarianism, refusing to enrol her American daughter in public school because she found it anathema that the state should have a role to play in education, or anything. Sometimes its easy to dismiss what happened in the USSR as history, and to be confused by why so many people find state involvement in people’s lives potentially dangerous—Sullivan’s book did well to remind me that there’s some context to that.

I wasn’t sure what the through lines would be from Page’s life to that of Svetlana Alliluyeva in Stalin’s Daughter, except that Rosemary Sullivan, who wrote the book, appears as a character in Journey With No Maps, which is very cool to consider. Svetlana’s story shows an extreme version of a pattern set out in Page’s biography, that of a woman being defined by her relationships to men. I suppose Svetlana’s is also a story of being in a family with a diplomat—she is paraded out during her father’s dinner with Churchill in 1942—even if the diplomat in question is Stalin. And there is unrequited love in both books—before her marriage, Page was deeply involved in a relationship with a married man that she never entirely got over; Svetlana, sadly, falls passionately in love with one man after another. We learn about Khrushchev’s Thaw, which brought with it political instability—Soviet tanks would crush a Hungarian uprising in 1956, at the same time that P.K. Page’s diplomat husband Arthur Irwin was working with Lester B. Pearson to ease tensions during the Suez Crisis. In 1967, Svetlana would defect to America. Also, Frank Lloyd Wright’s third wife is a bad bad woman, in that she brought Svetlana into an architectural cult and stole all her money. Seriously. The book was such a page-turner, Sullivan is such a wonderful biographer, and Svetlana Alliluyeva was a fascinating woman with literary talent and a fierce intelligence that was so often undermined. I found it interesting to learn how much she resisted all notions of socialism and communism after her experiences of totalitarianism, refusing to enrol her American daughter in public school because she found it anathema that the state should have a role to play in education, or anything. Sometimes its easy to dismiss what happened in the USSR as history, and to be confused by why so many people find state involvement in people’s lives potentially dangerous—Sullivan’s book did well to remind me that there’s some context to that.

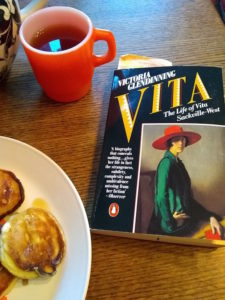

Next up was Victoria Glendinning’s biography of Vita Sackville-West who, as with P.K. Page, I have heard about and read about more often than I have actually read her work. Oh my gosh, this book! I just kept reading allowed my favourite sentences. 1956 factors here as well: “Shortly before they left on a fortnight in France in October—the Suez crisis was raging in England—Vita was stung on the neck by a wasp while giving tea to Megan Lloyd George in the garden.” The whole book is rich with such strange and perfect details, partly because Glendinning is a first class biographer (though Sullivan and Djwa are just as good) but also because she left so much material, her letters and diaries. On page 128 Katherine Mansfield dies, which is 1922—and Mansfield had been a huge influence on P.K. Page in her formative years, and Page carried on a critical dialogue with Mansfield as she read the author’s work. Page was also devastated by Mansfield’s death, though it had taken place more than a decade before Page would learn of it, but she’d been reading Mansfield’s stories in 1930s imagining the author as a kind of contemporary, that she was somewhere out there in the world. Anyway, as per Vita, when Mansfield died, she left a space in the life of Virginia Woolf, a space that would be filled by Vita herself, and Woolf was another great influence on PK Page.

Next up was Victoria Glendinning’s biography of Vita Sackville-West who, as with P.K. Page, I have heard about and read about more often than I have actually read her work. Oh my gosh, this book! I just kept reading allowed my favourite sentences. 1956 factors here as well: “Shortly before they left on a fortnight in France in October—the Suez crisis was raging in England—Vita was stung on the neck by a wasp while giving tea to Megan Lloyd George in the garden.” The whole book is rich with such strange and perfect details, partly because Glendinning is a first class biographer (though Sullivan and Djwa are just as good) but also because she left so much material, her letters and diaries. On page 128 Katherine Mansfield dies, which is 1922—and Mansfield had been a huge influence on P.K. Page in her formative years, and Page carried on a critical dialogue with Mansfield as she read the author’s work. Page was also devastated by Mansfield’s death, though it had taken place more than a decade before Page would learn of it, but she’d been reading Mansfield’s stories in 1930s imagining the author as a kind of contemporary, that she was somewhere out there in the world. Anyway, as per Vita, when Mansfield died, she left a space in the life of Virginia Woolf, a space that would be filled by Vita herself, and Woolf was another great influence on PK Page.

Like Page, Vita was a diplomatic wife, albeit a pretty unorthodox one. “Vita’s prejudices against the diplomatic life were confirmed, though she paid calls, attended and gave luncheons and dinners, as she had in Constantinople; she even gave away the hockey prizes. ‘I don’t like diplomacy, though I do like Persia,’ she told her father.” Later in her life, she was comfortable playing virtually no role in her husband’s diplomatic and political life at all—often to his displeasure. But Vita, like Page and Svetlana, made her own map, for what a daughter, a wife, a woman should be. She rankled at the limits permitted by society to her gender, and was ever resentful that because she was a girl she was not able to inherit her father’s estate and family home by which was tremendously attached and inspired. Though she did manage to buy a castle and live in a tower, so it worked out better for her than it might have for a lot of women. I was fascinated by the process of Vita moving from bohemian renegade to upper class conservative later in her life, as well as her nationalism in spite of her lack of appetite for her husband’s work. It’s such a surprising, but natural trajectory. Like Svetlana, Vita had many many love affairs, but she was the one who left lovers enthralled (and broke their hearts, though they would be forever devoted). Oh, and later in her life, Vita and her husband took to cruises, and when she’d visit Brazil she would find it quite differently than P.K. Page did (who found her experiences there transformative): “I think it is a beastly country and I never want to see it again.”

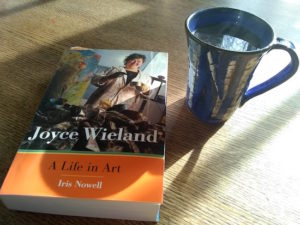

And then finally, another life without maps, that of artist Joyce Wieland, in Iris Nowell’s 2001 biography, Joyce Wieland: A Life in Art. Where there was no mention of the Suez Crisis at all, but Wieland, like Page, would also develop an affinity with Katherine Mansfield. No word on Mansfield and Svetlana—except no!! The evil Olgivanna Lloyd Wright who’d brought Svetlana into a cult and stole her money was the nurse who cared for Mansfield on her death bed, what????? Olgivanna and Mansfield were both pupils of George Gurdjieff, whose work would be meaningful to Wieland throughout her life. (And P.K. Page would become influenced by Gurdjieff through her connection with Leonora Carrington in Mexico. I don’t think Vita Sackville-West had much to do with Gurdjieff at all. I don’t know that she was so concerned with self-development. She had the confidence not to be…)

And then finally, another life without maps, that of artist Joyce Wieland, in Iris Nowell’s 2001 biography, Joyce Wieland: A Life in Art. Where there was no mention of the Suez Crisis at all, but Wieland, like Page, would also develop an affinity with Katherine Mansfield. No word on Mansfield and Svetlana—except no!! The evil Olgivanna Lloyd Wright who’d brought Svetlana into a cult and stole her money was the nurse who cared for Mansfield on her death bed, what????? Olgivanna and Mansfield were both pupils of George Gurdjieff, whose work would be meaningful to Wieland throughout her life. (And P.K. Page would become influenced by Gurdjieff through her connection with Leonora Carrington in Mexico. I don’t think Vita Sackville-West had much to do with Gurdjieff at all. I don’t know that she was so concerned with self-development. She had the confidence not to be…)

Anyway, I saw the Wieland exhibit at the McMichael Gallery in October and really wanted to learn more about her. Of the four women whose books I read, Wieland is the only one who attended a high school I can see from my bedroom (which is a mark of distinction for any life…) Her early life recalls Vita’s mother’s, in its illegitimacy and scandal (her father had left behind a wife and family in his native England) but much more destitute. She would be an orphan by age nine, and spend the rest of her childhood in the care of her older sister and family friends, but it was the Great Depression and not a great time for anybody to be taking in extra children. I loved reading about her experiences growing up in Toronto from the 1930s to the 1950s, the artistic scene in particular. I loved learning about Wieland’s interest in fashion design, and how that informed her art—and how her talent was nurtured during her years at Central Technical School under the tutelage of painter Doris McCarthy.

Once again, Wieland would be defined in relation to a man in her life, the artist Michael Snow—she’d spend a lot of time dismissed as ‘the wife of…”. Interesting to learn that she conceptualized his geese sculptures at the Eatons Centre in Toronto. Interesting too to learn that her art on the Toronto Transit System—which I tweeted about not long ago when we went to see her caribou, lamenting that we don’t have the vision anymore to make public art like that—was hugely controversial when it was installed; seems there never was a golden age of art appreciation. Or that the craftwork in much of her textile art was done by other people who employed, including her talented older system Joan—and she always took care that they got credit. Oh, and the sexism, as per P.K. Page. Unlike the three other women I read about, Wieland did not resist the label of feminist and that was refreshing (especially since all the women in my book stack so exemplified it). Like Page did, Wieland also worked very hard on behalf of Canadian artists and creators and tried to make a space where Canadian works could be celebrated as distinct from their American counterparts. Each of the women I read about on my holidays engaged with nationalism in singular and interesting ways—I’m thinking too of the way that Wieland would come to reevaluate her reverence for Pierre Trudeau, that it was never really reason over passion over all.

But then what kind of life would it be if it ever was? None of these books, nor these lives, would ever have reached the heights they did.

January 5, 2018

Measuring Life in Chesterfields

Can you measure a life in chesterfields? Or in couches, of sofas, or even settees? I’m beginning to think so. In university, my roommates and I had a set compiled of half a rumpled 1970s’ sectional reupholstered with a pineapple print salvaged from my parents’ basement and a red Ikea specimen that was literally made of styrofoam, and I don’t know where either of these eventually disappeared to—presumably the landfill. When Stuart and I moved to Canada in 2005, we were living on very little money, so couldn’t afford a couch, and purchased a futon instead, which seemed positively luxurious compared to sitting on the floor. It was also the first piece of furniture we ever bought, which seemed terribly sentimental (and it would stay with our family for years and years, eventually becoming our first child’s first proper bed, never mind that there was nothing proper about it…)

By 2007 we had arrived though, and we bought a proper couch from the Brick out on the Danforth. Yesterday we had a conversation about why we’d bought that couch exactly. “Because it’s really ugly,” we said. “It’s always been ugly.” Which is true. “It must have been cheap though.” “And probably we sat on it in the showroom.” Which would have clinched it, because it’s the most comfortable hideous couch in the world. Ask anyone who’s ever slept on it—and that’s a lot of you—and they’ll tell you the same. It is a giant stuffed toy of a couch, good for bouncing, and sliding, and also for naps. We were so incredibly proud of it, because it was even more grown up than a futon. And for the last decade that couch has been the centre of a lot of action, taking so much abuse from our two children who christened it in every way imaginable. So much so that the hideous couch has become even uglier, rumpled and sagging. Still loveable, still so comfortable. But we really felt it was time we got ourselves a couch that nobody in the history of the world has ever peed on.

It arrived this morning from Article, the Ceni Pyrite Gray Sofa, which has its own hashtag—our brown couch from the Brick certainly didn’t. And I’m absolutely delighted with it, its stylishness and comfort, that it wouldn’t look out of place in Don Draper’s office (but don’t worry—he hasn’t peed on it either). To complement it, we also bought a new coffee table, which has the incredible distinction of being the first coffee table we’ve ever owned that we didn’t take out of somebody’s garbage. Plus, the coffee table comes with book storage, and you know what that means—we have to buy more books. And we’re just very very happy here in this new era we’ve arrived in, of toilet trained children who don’t think that cushions are necessarily trampolines, being lucky enough to be able to afford a new sofa (which is as central to home as the kitchen table is), to live in the home we do in a place we love.

All of it is such a very very good life—and we look forward to barrelling through the next ten years on a couch as splendid as this one.

January 3, 2018

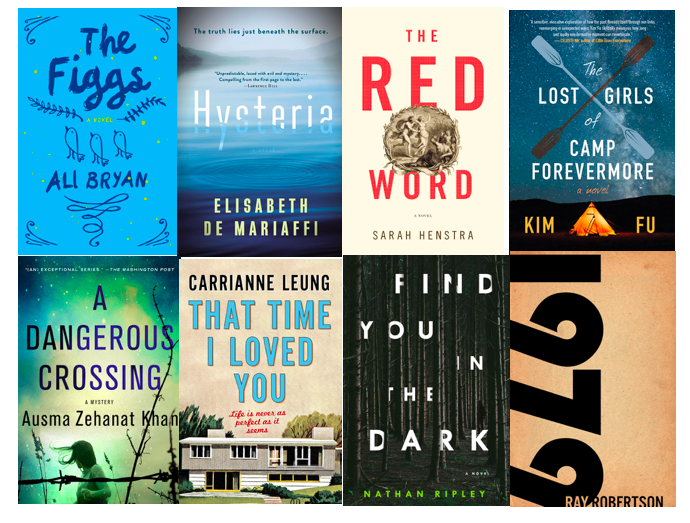

Looking Forward to 2018 Books

Happy New Year! I was on CBC Ontario Morning today talking about 2018 titles I’m really excited about. You can listen again here—I come on at 33.50.

Happy New Year! I was on CBC Ontario Morning today talking about 2018 titles I’m really excited about. You can listen again here—I come on at 33.50.