October 10, 2019

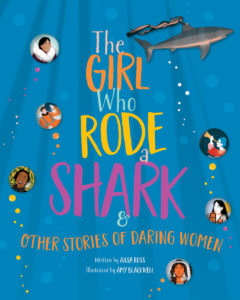

The Girl Who Rode a Shark, by Ailsa Ross and Amy Blackwell

I’m not yet bored of stories of brave and uncommon women, and this is not even a genre that began with Good Night Stories for Rebel Girls. Virginia Woolf published several biographical essay throughout her career—it was from “Lives of the Obscure,” in The Common Reader, that I learned about the Victoria entomologist Eleanor Ormerod, for example, and without Woolf we wouldn’t even know about Shakespeare’s Sister at all. Truth be told, I actually found Good Night Stories... a bit wanting…but that’s because I’d read Rad Women Worldwide before it, and liked it so much better.

But another similar book, The Girl Who Rode a Shark, by Ailsa Ross (who lives in Alberta!) and Amy Blackwell, has managed to live up to my expectations. My favourite bit is the Canadian content—we’re almost at the Roberta Bondar essay. And Indigenous hero Shannon Koostachin is included in “The Activists” chapter.

The women profiled in the book come from places all over the world, include many women of colour, and also women with disabilities. Even better—while many of the profiles are of historical figures, just as many are contemporary, young women who are out there doing brave and groundbreaking things as we’re reading. A few of these figures are familiar, but more are new to us, and their stories are made vivid and compelling through the book’s beautiful artwork and smart and engaging prose.

October 10, 2019

October

This month marks 19 years since I started blogging, and I’ve also been thinking a lot about where I was here a decade ago, when life was very different, when I was the new parent of a small baby and the universe was made of a million tiny little pieces that would eventually find their way together to make…my life. A life where the children go out of town for the weekend—WHAT? But yes, they went to Girl Guide Camp and Stuart and I were left on our own for 36 hours. So curious to slip back to the life that used to be, when days were wide open, we could walk until our feet hurt, and once the supper dishes were washed, we didn’t have to put anybody to bed. It helped that the day was golden, beautiful. We visited Little India in the east end, where we’d never been before, and then walked along Gerrard all the way from Coxwell to Logan, and it was so interesting and fun, and a great treat to return to that expansive life for a little while, and have my house clean. But oh, the children, with their complications and fascinations, and when they came home, we were glad to have them. Always, we are glad to have them. And lucky. And it occurred to me on Monday, when I was reading Theresa Kishkan’s blog, that I love her blog so much because she’s as mystified and fascinated by this particular thing as I am, the banal and extraordinary fact of the passage of time. How did we get here, far more interesting to me even than where are we going ever was.

October 8, 2019

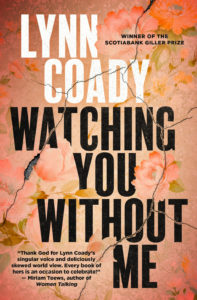

Watching You Without Me, by Lynn Coady

I’ve been a big fan of Lynn Coady for awhile now, since I read Mean Boy back in 2006. I absolutely adored her most recent novel, 2011’s The Antagonist, and I really enjoyed puzzling my way through her Giller Award-winning Hellgoing a couple of years later. Hellgoing, a book that, like the trajectory of Coady’s writing career, is packed with twists and turns, a resistance to the boring, conventional or expected. A resistance that continues right up her latest, Watching You Without Me, a thrilling and engrossing ride of a novel, a most unsettling but utterly captivating read.

Her protagonist is Karen, who returns home to Halifax after the death of mother to take care of things, and to sort out the future of her older sister, Kelli, who is developmentally disabled. The moment both Karen and her mother had been resisting for years, especially after an epic battle they’d had decades before when Karen voiced her refusal to be responsible for Kelli’s care and also blamed her mother for having her identity subsumed into that very thing. But the reality of the situation is more complicated than that, as Karen begins to realize as she becomes reacquainted with her sister and the household, whose demands are made somewhat easier with the curious presence of Trevor, her sister’s care-worker, who, it turned out, had come to play an important role in the family’s life while Karen was away.

But Trevor’s presence is also an uneasy and unsettling one. His familiarity makes Karen uncomfortable, she doesn’t really like him, he has “issues,” as they say, control issues in particular, and a propensity for flying off the handle. But Karen is also desperate, and vulnerable in the wake of her mother’s death, and she allows Trevor to continue to make a place for himself in the household, because he’s kind of a master manipulator, but also she needs all the help she can get.

Karen is a fascinating, solitary figure whose more recent history is glossed over, save her a recent divorce, but her lack of friends and confidantes is conspicuous. An elusive narrator, she sees what she wants to see, and does an effective job of shaping the narrative to her purposes, but there are moments when we see through to the story behind the story, and the story behind that, each of these worthy of novels onto themselves, so many questions—the complexity here is wonderful.

Karen’s story reminds me of the narrator of Helen Phillips’ The Need, recently nominated for a National Book Award. Another sinister book about the unrelenting demands of caregiving and how a person might crack underneath them to make some questionable choices. About how one might take whatever relief they’re offered, even if they know it’s a really bad idea, but it’s rather enticing, the opportunity for just a few moments of rest and also the assurance that somebody else, for once, is in control of the chaos.

Claire Tacon’s wonderful 2018 novel, In Search of the Perfect Singing Flamingo, also similarly explores disability and families, and the experience of being the adult sibling of a person with developmental disabilities, although the siblings’ parents are still alive in Tacon’s novel, and the idea of what happens once they’re gone just looms on the novel’s horizon. Coady’s novel, unflinchingly, takes the reader right there, that moment of the realization of so many parents’ fears for their children, but what is to be most feared actually arrives in the form of a saviour. And the unfolding story of just who Trevor is and what his intentions are results in a roller-coaster ride of a read—which is a remarkable feat when the reader considers that these are characters who barely leave the house.

October 7, 2019

Gleanings

- It is telling that this dedication is not to Stein herself, but to her words and sentences – those notoriously obscure, dense, allusive syntactical puzzles that require dedication and persistence to parse and comprehend.

- It’s lovely to choose your life again, even when you think you already appreciate it.

- Having breast cancer and knowing how little funding goes into research for metastatic breast cancer, and how it mostly goes into overhead and pink trinkets, has made me want to hate October.

- When I go into the kitchen and see the pot of hips on the table, I wonder how the summer passed so quickly.

- I am so grateful for this portal, and it’s always a delight when I hear that a post has inspired or moved someone, or just simply made them happy.

- It strikes me that reading Tove Jansson is like stepping through the back of the literary wardrobe into a Narnia-like world of magic and difference.

- The conservation area is located at #902 Ballyduff Road; small problem though, the road ends at eight hundred and ninety something. Beyond that was a very rough (very, very rough) track through the woods….

- Sometimes it’s fun to know next to nothing about a book prior to picking it up.

- Or the fact that I have been reading Tolstoy for decades and still only have the foggiest idea what a samovar is….

- If you are looking for consolation as a reader, you would be well advised to look elsewhere.

- Yet never has a colon done so much heavy lifting.

- I found her book in my building’s laundryroom’s bookshelf.

- If the bullshit-merchants have no shame about repeating themselves, their critics shouldn’t either

- There is a lot of work to be done out there, Readers! Kids need mirrors and windows!

Do you like reading good things online and want to make sure you don’t miss a “Gleanings” post? Then sign up to receive “Gleanings” delivered to your inbox each week(ish). And if you’ve read something excellent that you think we ought to check out, share the link in a comment below.

October 2, 2019

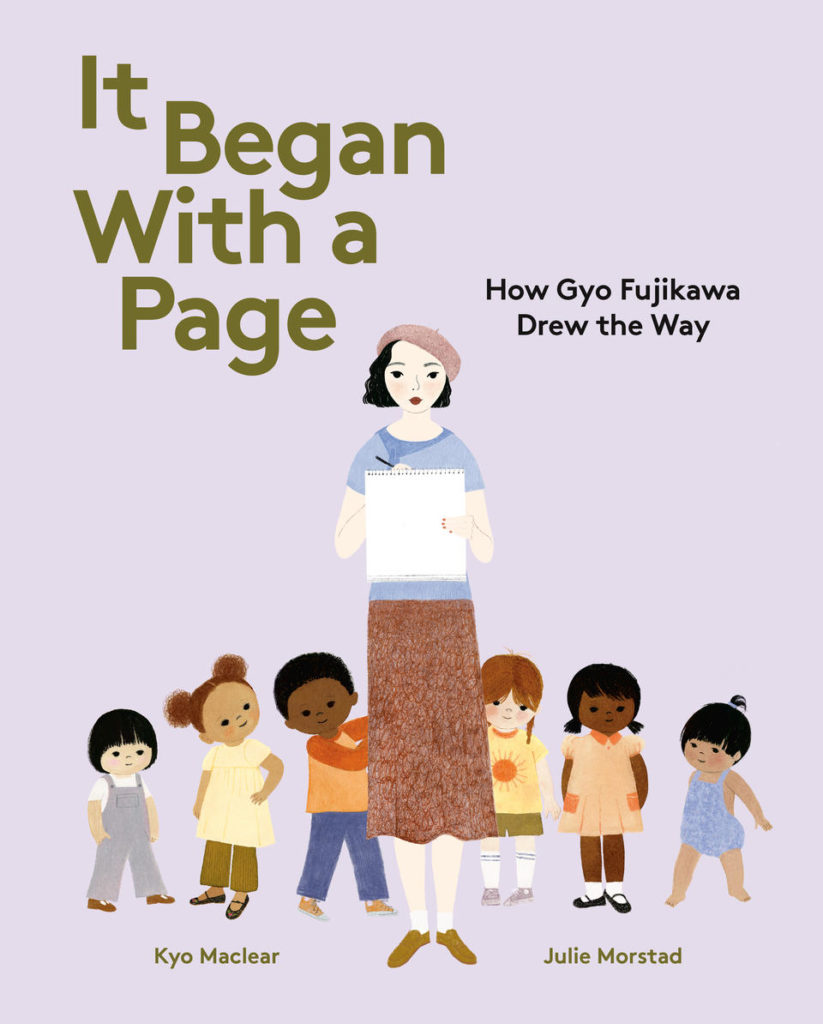

It Began With a Page, by Kyo Maclear and Julie Morstad

It Began With a Page, the new picture book collaboration by Kyo Maclear and Julie Morstad—who are already known for their picture book biographies(ish) of Julia Child, Elsa Schiaparelli, Anna Pavlova (illustrated by Morstad, written by Laurel Snyder), and Virginia Woolf (written by Maclear, illustrated by Isabelle Arsenault)—has everything. And to have Kyo Maclear, a leading Asian-Canadian author writing about THE pioneering Asian-American children’s author/illustrator, with illustrations by Julie Morstad who does such justice to her source material. Which is, of course, Gyo Fujikawa’s babies, an adorable array of little people from different ethnic backgrounds, all playing together—Fujikawa has clearly been an inspiration to Morstad since the beginning of her career. But what contemporary readers might not appreciate until reading It Began With a Page—which tells Fujikawa’s life story—is that it wasn’t long ago that picture book illustrations of children with different skin colours all playing together was revolutionary, and before that even not condoned.

Which is a convenient metaphor with which to tell a story of a society in which, just say, people from a certain ethnicity have their land and belongings confiscated and are sent to concentration camps. Although Maclear eschews metaphor altogether here, and sticks with the facts: “In early 1942, terrible things were happening. Bombs and gunfire rocked the world. America was at war with Japan. Kyo was shocked to discover that anyone who looked Japanese or had a Japanese name was no suspected of being the enemy… Gyo’s family was sent to a prison camp far, far away from their home.”

But first: “It began with a page, bright and beckoning.” A five-year-old girl with a pencil in her hand. “The dance and glide of a line. How a new colour could change everything: a bright splash of yellow, a sleep stroke of blue.” The girl fills her pages with drawings, and as she grows older, her talent is natured by a supportive teacher who pays for her art lessons Gyo Fujikawa is one of the few girls, let alone Asian-American girls, who goes to college in 1926. She travels to Japan, her ancestral homeland, to learn about the tradition of Japanese brush painting, and after she returns to America gets a temporary job designing books at Walt Disney’s studio in New York. Which means she is far away from her family when the Japanese internment takes place, but the distance only increases her heartbreak at what is happening in her country.

After the war, Fujikawa continues to work as an artist, and Maclear shows her awareness of the dawning civil rights movement. “Still, there was so much that hadn’t changed. At the library and bookshop, it was the same old stories—mothers in aprons and fathers with pipes and a world of only white children.”

But when Fujikawa submits her manuscript featuring “Babies! Chubby cheeked, squat-legged, bouncy-bottomed babies,” the book is rejected. “No to mixing white babies and black babies. It was not done in early 1960s America, a country with laws that separated people by skin colour.”

Fujikawa, however, does not give up on her vision. And eventually, the book is accepted, and is a huge success, the beginning of an incredible career for this illustrator whose drawings would create “a bigger, better world.”

The story includes a timeline of Gyo Fujikawa’s life, and photographs, and a note from Maclear and Morstad to readers about Fujikawa’s legacy (“Gyo as a TRAILBLAZER…and a RULE BREAKER”) was and how her family supported this book (Fujikawa died in 1998), providing access to stories, photos and archival materials.

October 2, 2019

Autumn Reads on the Radio

I was on CBC Ontario Morning today talking moody autumn reads that match the weather, but which also feature some glorious golden hues. If you missed it, you can catch my column on the podcast at 33.30.

October 1, 2019

Life Stories

In terms of books, fiction is my default, the first thing I pick up, the books I tend to write about, no matter how interesting I find actual real life people, and the way that nonfictional characters’ stories are often as rich with symbolism and metaphor, and teach me things about the world I never understood before. No matter too the way that I am always interested in memoirs, which means my pile of life stories to be read is embarrassingly high, and one of my reading projects this fall is the absolutely satisfying one of actually reading them. So here’s my start.

Tiny Lights for Travellers, by Naomi K. Lewis: to say that this is a story about a woman who discovers her grandfather’s diary documenting his escape from Nazi Europe and decides to retrace his steps… is far too simple to describe what’s happening in this book. For starters, Lewis is the least likely person to ever end up in a travel memoir. She has self-diagnosed herself with an actual affliction of being directionally-challenged, and she frequently gets lost in her own neighbourhood. She’s also still raw from her recent divorce, and has a complicated relationship with her Jewishness, as did her grandfather who escaped Nazi Europe, for that matter. But she decides to follow her grandfather’s steps anyway, but her real journey is one that’s internal as she navigates her connections to place, religious identity, marriage, secularism, sex, history, baggage (literal and otherwise), family, her own face, and more. It’s a fascinating and illuminating adventure, and a really beautiful book.

*

In My Own Moccasins, by Helen Knott: I had heard wonderful things about Helen Knot’s memoir, In My Own Moccasins, but I must confess that I bought it because it’s a pocket-sized hardback, a gorgeous book you can hold in one hand, and I couldn’t resist it. Good thing too, because the book is as gorgeous inside as out. Knott tells her story, which is one of seeming contradictions. She grew up in a family that was troubled and loving, she emerged as an activist and leader but struggled with drug and alcohol addiction, all of this overshadowed by her family’s history of colonial trauma and her own experiences of sexual assault. The story is told outside of chronology, each section of the book circling toward the central point, which is the violence of colonialism and also the story of resilience, as Knott fights her way out of darkness and claims the cultural heritage that colonialism would have denied her. It’s a harrowing and generous story, rich with wisdom and power.

*

To Speak for the Trees, by Diana Beresford-Kroeger

Reading Ariel Gordon’s Treed last spring changed the way I see the world, and certainly heightened my reverence for trees, so I was excited to read Beresford-Kroeger’s To Speak for the Trees, a memoir by the acclaimed scientist. A memoir that read somewhat incredulously if it were a novel, because surely it couldn’t really happen that way. Beresford-Kroeger born to an English aristocrat and his Irish wife, who become estranged, and then both die, leaving their daughter an orphan. She could very well be sent away to an orphanage, but instead is left in the care of a neglectful uncle, but she’s also adopted by members of her community and schooled in ancient Celtic wisdom. And she basically spends her career as a botanist proving with science all she’d been taught here, plants as cures and tinctures. It doesn’t hurt that she’s also incredibly intelligent with a photographic memory, and in conventional school it soon becomes clear that she’s an extraordinary pupil. Ireland was long ago deforested by the English, to fuel English industry but also to rob the Irish people of the spiritual power that came with the trees, and Beresford-Kroeger does not get to properly experience a forest until she immigrates to Canada, where she has spent her adult life. She writes about the importance of biodiversity, her quest to find and preserve rare trees, and how trees are instrumental in our battle against climate change. A curious and fascinating book.

*

Outside In, by Libby Davies

Libby Davies’ memoir of her career in activism, Vancouver municipal politics, and as a Member of Parliament in Ottawa was just the balm I needed in the midst of an election that, as expected, as turned out to be stupider than stupid. It’s inspiring, so interesting, and points out the opportunities and challenges of politics, and it was just so wonderful to read about someone driven to service, to make the world a better place, instead of seeing politics as a game, as so many others do (and Davies shows this). An activist since her teen years, Davies’ story is rich and the book is absorbing. It made me believe in the possibility of a better world, and renewed a little bit of my faith in the electoral system.

September 30, 2019

Gleanings

- In praise of kind ruthlessness: a writer’s appreciation of the intelligent non-expert

- This is a space to indulge the author’s enthusiasms, without recourse to chasing trends or fashion and with no claim to comprehensiveness or universality.

- I’ve confessed here before that I can have trouble staying “objective and professorial” during discussions of Gaudy Night because I love the novel so much.

- Deep delight, in a moment of mania. That was me, in the night, writing by starlight, telling the story over and over again.

- In simplifying my choice, I’ve given myself a greater chance of success, and created an opportunity for a cohesive collection and stronger personal aesthetic.

- For me, being lost unexpectedly turned out to be an entirely internal exercise.

- It is all ebb and flow. Some periods will feel quite desperate, and at other times we will feel light.

- What happens after a protest?

- I still have emails saved in a folder called SELLOUTS GET SENSITIVE.

Do you like reading good things online and want to make sure you don’t miss a “Gleanings” post? Then sign up to receive “Gleanings” delivered to your inbox each week(ish). And if you’ve read something excellent that you think we ought to check out, share the link in a comment below.

September 26, 2019

On Beauty

If there is one mistake of mine that it’s really important to me that my children could learn from, it is this: leave your eyebrows alone. More important than not smoking or getting ill-advised tattoos, because there is no coming back from eyebrow ruin. During the early years of my life, I had perfectly acceptable, unremarkable eyebrows, and I could have stayed that way, were it not for a teenaged need to perform womanhood with stupid grooming rituals.

So I went and got my eyebrows waxed, and waxed, and waxed and waxed, and there was a point in 2001 where they were tiny little lines, skinnier than I’ve ever been, and there was also the women who did my brows the day before my wedding who nicked me with the tweezers and made me bleed, so I gave her an extra big tip so she would feel less bad about the whole thing, and being a woman is so idiotic.

And then one day a couple of years ago, I decided I didn’t want to wax my eyebrows anymore. I didn’t even want to tweeze them anymore, standing before the bathroom mirror, hair-by-hair, each pluck making me sneeze. I don’t have time for that, because it always grows back. The same reason I’ve sworn off dieting, and colouring my hair, and running on treadmills—the whole thing is Sisyphean, and I refuse to be pushing a boulder for the rest of my life. These are losing battles, and I will not engage.

But the result now is that I have terrible eyebrows, sprawling and patchy. Would be that after all the waxing, my eyebrows would have thinned out altogether, but instead they’ve grown back in wide but with bald spots, a shape that is so far from a shape, and I just don’t care. And also I do, because I’m already on my fourth paragraph writing about it. But I just can’t go in for the incessant demands of grooming, and most of the time I don’t, which is one great benefit of being in a romantic partnership with someone who is terrifically far-sighted.

I was listening to a podcast today (which is the way that I start most of my sentences lately) when the host came on with an ad for some kind of skin care product I wasn’t paying proper attention to, and she talked about how much she loved her nightly skin care regimen, how it was just so fantastic that it gave her “me-time,” and I almost died of despair right then. The saddest thing I’ve ever heard, though perhaps I’m reading more into this than I should be. It is possible that no podcast host is quite as enthusiastic about the product she’s endorsing as she sounds like she is, and I actually really hope she isn’t, because that’s the saddest excuse for “me-time” I’ve ever heard.

It is also possible that she has nicer skin than I do. Most people do. Earlier this year, I turned down a prescription for rosacea from my dermatologist, so I’m hardly an expert on any of this. I’m just kind of lazy when it comes to grooming, and also would prefer to squander all my money on books instead.

Which is not to pass any judgement on those people who heavily invest in their aesthetic appearance—they’re are a million ways to be a woman after all, and who am I to tell another person what to do with her body, but this is kind of just my point, that the whole world is actually telling us what to do with our bodies, and I wonder sometimes if the whole thing is a conspiracy to keep us from doing anything more useful.

All those boulders we’re pushing, even once we’ve refused to push the boulders. I have no idea what liberation might look like.

September 25, 2019

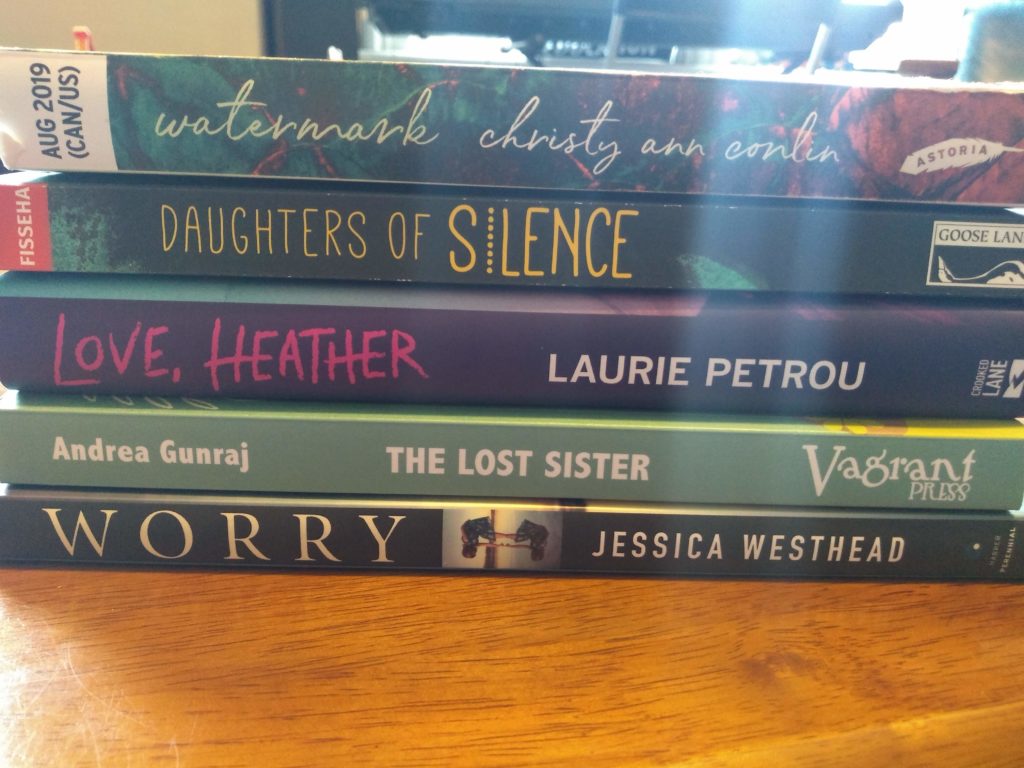

Love, Heather, by Laurie Petrou

“Why would anyone read a book instead of watching big people move on a screen? Because a book can be literature.” —Annie Dillard, The Writing Life

I thought I knew what I was getting with Laurie Petrou’s new novel Love, Heather, a book so informed by movie tropes—from Heathers to Mean Girls—that it seemed instantly familiar, like something I had read before. A high school setting, a relationship under strain—Stevie and Lottie have been friends since childhood, but they’ve started high school, and everything’s changing. Plus Lottie’s parents are splitting up, which means that Stevie is losing the stability she’d counted on from her friend’s family since her own parents divorced. And Lottie seems distant, intent on new friendships with a clique of girls in their grade, and this tension only magnifies Stevie’s social awkwardness, so that Lottie pushes her further and further away.

And then suddenly Stevie is all alone, cast out of the cool girls’ group, her missteps in navigating a new social order that she still doesn’t understand bringing her bullying and ridicule. She finds some solace in her love of old movies, and on her Youtube channel where she talks about film, but it isn’t enough, and eventually the bullies find her there as well. It seems there is no escaping them.

But then justice arrives in the form of a new friend, Dee, whose brazenness and daring makes Stevie nervous, but also invites her admiration. With Dee by her side, Stevie begins to make new friends, connecting with other misfits who don’t conform to the status quo. And under the influence of the charismatic Dee, and all the movies they’ve seen, the group begin to seek revenge against everyone who has wronged them, the cliquey girls, the entitled jocks. An exhilarating kind of justice, each act marked with a signature, “Love, Heather,” in homage to the Winona Ryder flick. But then things begin to spiral out of control, and there are questions about whether Dee is taking things too far, but do Stevie and her friends have the power to stop her now that the wheels of vengeance are in motion? When does a victim become a perpetrator? The hero the anti-hero? Where do you draw the line?

And then there was a twist, in this conventional-seeming story. A novel that’s billed as YA, and which underlines that such distinctions are kind of irrelevant, or at least uninteresting. Underlining too the message of the book, which is that adults have no idea what’s going in teenagers’ lives, no matter how well-intentioned they are. The twist in this book: I never saw it coming, and it cast the entire story in a new light, and demonstrated that Laurie Petrou is a master of her craft. Funny how this is a novel that’s so informed by film but which is precisely so powerful because it’s a book and does what only a book can do.

Not a novel for the faint of heart, Love, Heather, is dark and troubling, pulls absolutely no punches, but the reader will be rewarded for her bravery. By how the novel itself is a testament to the powers of literature, but also by how Petrou complicates so many contemporary conversations, which is what our discourse needs right now—writers who dare to stare down the darkness and emerge with important questions, instead of the simple answers we’ve been hearing for so long.