October 31, 2019

How to Organize a Literary Event in 48 Hours

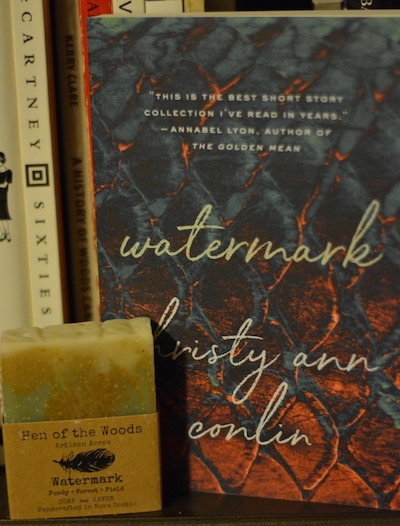

More than a month ago, I emailed my friend Nathalie and asked her if she’d attend the Toronto Public Library event with Christy Ann Conlin, Megan Gail Coles and Elisabeth de Mariaffi, and she replied with an enthusiastic YES, as you would, with a lineup like that. But then the event was cancelled after the Toronto Library was called on to cancel its provision of space to a speaker whose hate-speech about trans people is just one of the many awful things about her, and they refused. And so many authors and artists have cancelled their Toronto Library event in solidarity with the trans community, which is important and the right thing to do—but it also means that Christy Ann Conlin was coming to Toronto all the way from Nova Scotia for her very first reading in the city, and she had no event booked. So what to do?

I hadn’t properly understood the situation until Monday, or else I would have stepped up sooner, but once I’d figured it out, it wasn’t long before I had my inspiration. Right in the middle of dinner, in fact. “What would you think” I asked my husband, “about us having twenty people over for a literary event in our living room?” And my husband was so excited about me having a wild inspiration for which he would not be obligated to build a website that he agreed without hesitation. And so I sent an email to Christy Ann in Nova Scotia, and once she said she was in, there was just one more email to set the wheels in motion.

I had to email Nathalie and ask if she would be up for some custom mixology—and she agreed. Thank heavens, because everybody knows you can’t have a party without an official cocktail… (Nathalie invented three different cocktails, all with Nova Scotia spirits: “Minas Basin,” “It All Went Pear-Shaped,” and “Juniper and Apple Shrub.”)

And next, we needed people to fill my living room in 48 hours notice, but they came, a wonderful collection of generous, book loving people who were happy to welcome Christy Ann to Toronto. They filled my home with the most wonderful bookish spirit (and all got to take home custom Watermark soap from Hen of the Woods—what a treat!).

It was wonderful! Friends and neighbours came, a literary community of amazing readers and writers, including Christy Ann fans who I got to meet for the first time, plus a very exciting guest—Amy Spurway, of Crow fame, who was in town for the author’s festival. We ate food, sipped delicious drinks, made great conversation, listened to Christy Ann read from Watermark, and I got to ask her questions about her career and her book, and she was just so kind, and gracious and terrific. Throughly entertaining and delightful, and we were all so lucky to be part of it together, but me most of all, because I got to experience it without leaving the house.

October 30, 2019

It’s Not About the Vision Board

I want to go back to Jia Tolentino’s Trick Mirror, the parts about scams and delusions. That we exist in a moment where people are trying to sell us their 5 simple steps to becoming millionaires, or having body confidence, or achieving career success. That the only difference between you and that superstar you emulate is something corny like, “She dared to dream, and then she did it.” I have to confess to a mighty aversion to vision boards, especially since the images are usually cut out from magazine advertisements. Do I really want my vision to be borrowed from an ad for Hyundai? What are the limits to empowerment by hashtag?

And yet. A thing I’ve learned in the last few years, during this year in particular, is that we have more power than we realize. The point, of course, is just to use it, and certainly confidence is a factor. I turned 40 this year and what this new decade has delivered me is the confidence to realize I really do have something—skills, knowledge, experience and insight—to bring to the table. After a decade and more of not taking myself too seriously (because people who do can be insufferable) I’ve learned the value of doing so—while not being insufferable, I hope.

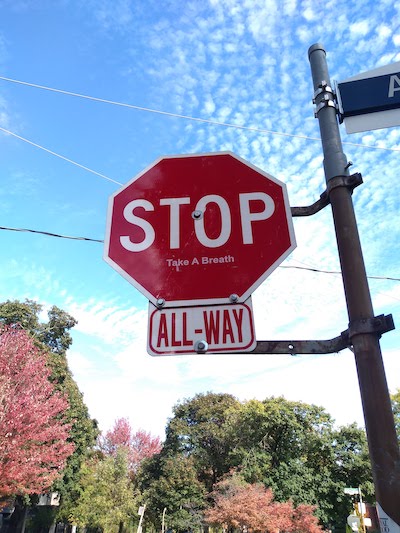

But it’s not about the vision board. It’s not even about “daring to dream big.” Instead, it’s about looking at the world head on and figuring out what needs doing. Asking “What if?” and daring to follow through. It’s about the doing, not the dreaming.

I note this example all the time, but it’s emblematic of many other things I’ve achieved on a larger scale: when my neighbours had a baby, I brought them a loaf of banana bread. And in doing so, I made our street, this world, a place where things like that can happen. A small thing, but I don’t discount the value of small things. I think they’re everything.

Anyone who attends a protest makes a world where people care about things. Anyone who reaches out to someone in need makes a world where people care about people.

The foundation is an understanding that you matter, and therefore the things you do will matter. And then you’ve got to do the things, which is where, of course, the work comes in.

October 28, 2019

Gleanings

- He encouraged us to think less in terms of tying the word “professional” to the idea of making money and more toward the idea of what we are doing as an integral part of ourselves.

- Can I make Saskatoon pie with dodgy Toronto berries?

- It’s inspiring to me how women, throughout time, have continued to create art.

- It was page 236 before I finally caved and looked up a picture of The Dress

- The thing is, I’ve been all over the place, and can’t really settle on any one topic…

- The monarchy is a helluva drug, you guys.

- I’ve been on page 9 of Ducks, Newburyport for some days now.

- Here’s the foolproof way to write your story faster: identify the scenes you are avoiding and get them over with.

- If I’m feeling tired, I open the file and aim to do just one thing.

- Happy second anniversary to our east end Toronto silent book club!

Do you like reading good things online and want to make sure you don’t miss a “Gleanings” post? Then sign up to receive “Gleanings” delivered to your inbox each week(ish). And if you’ve read something excellent that you think we ought to check out, share the link in a comment below.

October 25, 2019

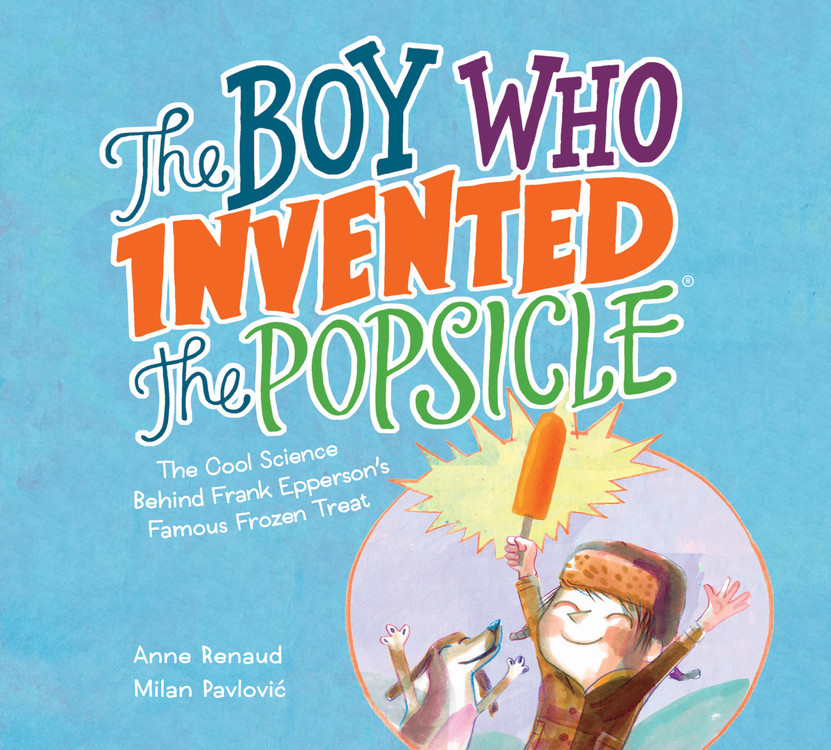

The Boy Who Invented the Popsicle, by Anne Renaud and Milan Pavlovic

For some reason, unless they happen to encyclopedic catalogues fun to flip through but with no overarching narrative, non-fiction gets short shrift with the young readers in my house. We’ve got a whole stack of titles about history and animals, dinosaurs, guides to crafting and science experiments, none of them appreciated as well as they should be, and my children read Archie comics to tatters instead.

But The Boy Who Invented the Popsicle, by Anne Renaud and Milan Pavlovic, is the exception to that rule, primarily because it’s a fabulous hybrid of a book—a great story that’s fun to read aloud; a biography based on Frank Epperson who really did invent the Popsicle; a gorgeous book with great design (endpapers to die for!); and it’s got science experiments—on mixing oil and water, how to make fizzy drinks, how to lower the freezing point of water—each one connected to the narrative, which is not only engaging, but also demonstrates the experiments’ real-world implications.

One of my favourite picture book biographies ever is Monica Kulling’s Spic-and-Span!: Lillian Gilbreth’s Wonder Kitchen, and The Boy Who Invented the Popsicle is kind of a companion, a story that blends the scientific and domestic realms, that shows how having children can inspire an inventor’s ideas, a story that makes the familiar extraordinary by taking an every day item (the popsicle!) back to its origins. It also shows how childhood dreams can transform into reality, and how curiosity and an insistence on asking questions can serve a person throughout his life.

October 24, 2019

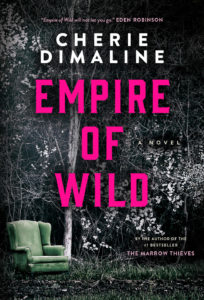

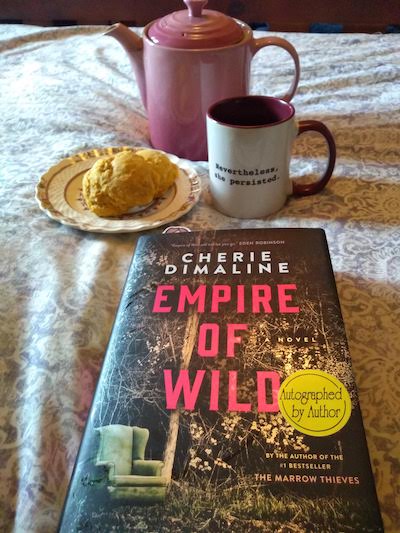

Empire of Wild, by Cherie Dimaline

How does an author follow up a success like The Marrow Thieves, Cherie Dimaline’s bestselling novel that won so many awards and prizes that they ran out of room on the cover? The most straightforward answer I can think of was also Dimaline’s herself, which was to publish Empire of Wild, a book that’s unabashedly excellent, gripping, funny, gorgeous, and dark. I read this book when I was taking part of in a read-a-thon last weekend. No, not that one that is my life, but the other one, raising money for metastatic breast cancer research. And Empire of Wild was the perfect novel for this experience—I couldn’t put it down, even if I’d wanted to.

It’s a book that reminded me a bit of Bad Ideas, another one of my favourite novels this year, about impossible love and what it means to believe in it. Empire of Wild begins with Joan, whose husband Victor has been missing for almost a year. He’d left the house after an argument they’d had about selling her family’s land. Hasn’t been seen since, though Joan’s not given up hope of his return just yet. And then one early morning, nursing a hangover, Joan walks into a revival tent in a Wal-Mart parking lot and discovers a man she knows is Victor, but he’s also a preacher whose name is Eugene Wolff. So who is he anyway? And what’s up with these holy rollers who seem to turn up in Indigenous communities who are making deals with big mining companies? Add to the mix a Rogarou, a werewolf-like creature from Metis stories, and you’ve got a plot-driven thriller on your hands.

Will Joan succeed in finding her husband again? Is Victor even still alive? With her Johnny Cash-obsessed nephew riding shotgun, Joan sets out to discover the answer to these questions, risking her own life in the process, and the result is an absolute terrific read, as powerful as it’s propulsive, plus the humour even in the darkness, savvy and self-aware lines like, “Sure hope those jackasses haven’t built over the spot. If they have, I hope those scary movies having it right and building over old Indian stuff makes your kids disappear into televisions.”

October 23, 2019

We are stardust, we are golden

One single quotation that bugs me in its vacuity even more than Madeleine Albright and her special place in hell for women who don’t help other women is that excerpt from a poem by Rumi that goes, “Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing, there is a field. I’ll meet you there.”

A line that maybe isn’t so offensive on its own, and I think that Rumi was talking about the spiritual realm, but I’m not sure it really applies here on Earth in the meantime, where people who insist on hanging out in that proverbial field are likely to come home at the end of the day with black eyes and bruises (because they’ve been cavorting with neo-Nazis), and possibly they’ll also have measles.

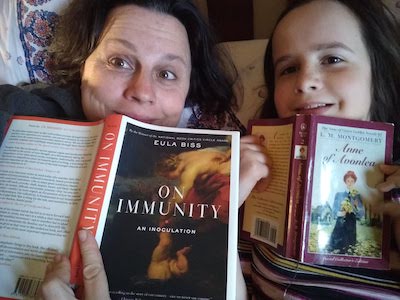

So, yes, Rumi, I will meet you there, but in the meantime, there’s the land right here before the field beyond wrongdoing and rightdoing, where we’re all trying to puzzle out this thing called existence and how to get along with each other, to do better than emblematic opposition, us and them, love is a battlefield. Where we need better metaphors, which is the central thesis of Eula Biss’s On Immunity, in which she uses the issue of vaccination to explore ideas of societal (dis)trust and polarization (and also the history of public health, and motherhood, and everything).

It’s not quite as simple as shrugging off right and wrong, heading out to the field. Different strokes for different strokes. Because of course, in innumerable ways, our lives and our choices all intersect. There is indeed such thing as society, and a public of which each of us are a part. Eula Biss calls on the work of Rachel Carson, who writes, “For each of us, as for the robin in Michigan or the salmon in the Miramichi, this is a problem of ecology, of interrelationships, of interdependence.”

Biss writes, “We are…continuous with everything here on Earth. Including, and especially, each other.”

My favourite part of On Immunity is in the endnotes, when Biss credits the women in her personal circles “who complicated the subject of immunization for me.” (Emphasis mine.) This same idea is repeated in the book’s acknowledgements: “I am grateful to the community…who complicated my thinking, argued generously, and pointed me in new directions.”

(In the endnotes, she goes on to explain her use of “mothers” when she might have used “parents” throughout the text. “This does not mean that I believe immunization is exclusively of concern to women, but only that I want to address other mothers directly. In a culture that relishes pitting women against each other in ‘mommy wars,’ I feel compelled to leave some traces on the page of another kind of argument…that does not reduce us, as the diminutive mommy implies, and that does not resemble war.”)

I first read On Immunity in 2015, which seemed like a polarized period at the time, but appears somewhat utopian when one looks back from our post-November 2016 world. And in the years since I read the book, I’ve continually returned to that idea of complication as a kind of service, a gift, something to be grateful for. Not always succeeding in my understanding, of course, failing more often than not, because it’s no small thing, to be grateful to the people who complicate your vision, your understanding. An astounding and rare feat of generosity, in fact, to be grateful to the people who keep the world from being simple…but this is the kind of achievement that I’m aspiring to, a way one might make it here in this place entrenched by ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing. This is how one might get beyond this place and manage to still have a soul.

“…it isn’t the clinging to answers but the embracing of ignorance that drives science,” Biss writes, but not just science—it drives everything. And to embrace ignorance is another way of asking to make it complicated. Tell me how the medical establishment has a centuries-old habit of undermining women’s knowledge, and that some of the first public health initiatives had people vaccinated at gunpoint. Tell me (as Biss does) how “a refusal to vaccinate falls under a broader resistance to capitalism,” but then complicate that. She writes, “But refusing immunity as a form of civil disobedience bears an unsettling resemblance to the very structure the Occupy movement seeks to disrupt—a privileged 1 percent are sheltered from risk while they draw resources from the other 99 percent.”

Or tell me how Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring alerted the world to the dangers of DDT, but also inspired a line of thinking that is not disconnected from the fact that one African child in twenty now dies from malaria as DDT is now discouraged for use against mosquitos. “For each of us,” as Carson herself said, “this is a problem of ecology, of interrelationships, of interdependence.”

It’s complicated. As they say.

Biss rejects the possibility of a middle-ground on vaccinations as facile, a middle-ground simply reinforcing the binary or this or that, and a divide instead of a connection, when the reality of most things is not so neat and simple. Bad guys and good guys? “[M]ost people are both,” writes Biss, and then quotes Naomi King, who knows something about monsters, because her father is an author called Stephen. She says, “If we demonize other people and create monsters out of each other and act monstrous—and we all have that capacity—then how do we not become monsters ourselves?”

On Immunity is preoccupied with the metaphor of vampires, and Dracula, but this passage had me thinking of Frankenstein, or rather Dr. Frankenstein, who, in creating a monster, has himself been transformed in into a monster, at least in the public consciousness.

However, now we’re back here with Rumi and the field beyond, basically, imagining that monstrosity is relative, but here’s the thing: I do think some monsters are real. And there is a distinction between the people who complicate things, and the people who set those things on fire. There is arguing generously, and there is arguing disingenuously, dangerously. Dog whistles. (That point where you start asking: am I being paranoid? Akin to someone who regards the polio vaccine as an global conspiracy?)

Possibly one benefit to restricting the bounds of your argument to apply to mothers, when certainly lessens the likelihood that you’re having your ideas complicated by someone who keeps body parts in the freezer, though no doubt (it’s complicated) there are even exceptions to that rule.

But now I’m back to Dr. Frankenstein again, and I don’t know what to do, but maybe complicatedness is the point. Complicatedness is reality. And the point is not untwining, but the twine, like ivy, and now I’m thinking of Biss’s final metaphor—for the body, for society. A better one than war, instead, the garden.

“The garden is unbounded and unkempt, bearing both fruit and thorns. Perhaps we should call it a wilderness. Or perhapscommunity is sufficient.”

A wild tangle. An exasperating mind-fuck. Sustaining, and but exhausting. Maybe that’s exactly what it’s supposed to be.

I reread On Immunity because it’s a Book Club Pick for the Mom Rage Podcast, a podcast which I’m embarrassingly enthusiastic about. I think they’re going to be talking about it on next week’s episode, but if you haven’t yet, you might as well just listen to all of them.

October 22, 2019

Reading All Day

The Turning the Page on Cancer Read-a-thon took place the very same day as the Waterfront Marathon here in Toronto, which got disproportionate media attention, really, considering that some slackers had completed their race in a couple of hours, but I was reading all day.

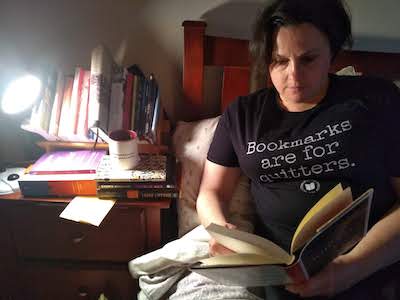

The event kicked off at 8:00, and I was so excited that I woke up before my alarm, taking a quick shower and donning my read-a-thon gear, which was track pants, my “Bookmarks are for quitters” t-shirt and “Fuck Off, I’m Reading Socks.”

I started off with a reread of Eula Biss’s On Immunity, which the Mom Rage Podcast will be discussing as a book club pick next week. (I read the book for the first time in 2015, and loved it. So happy to revisit it.) Reading with a pen in hand, which I never seem to do anymore, though I keep resolving to. But the read-a-thon was all about immersion, and I’d already marked up the volume the first time around, so there were underlines and notes in the margins. I look forward to writing a bit more about the book soon.

We’d envisioned buying my children whistles so that they could dance around the house cheering me like good coaches, and the idea of whistles appealed to them a lot of noise reasons, but then we remembered our resolution to avoid plastic crap (and also noise reasons) so the whistles would be metaphorical. Everyone in my family was terrifically supportive of my endeavour, which was basically lying in bed all day disguised as altruism. Stuart made waffles, and brought me tea, and Iris and Harriet both joined me for a while so I wasn’t reading all alone. (And yes, I loved that Harriet was so happy reading Anne of Avonlea.) Later, I would be delivered the most terrific grilled cheese sandwich.

True confession? 8 hours weren’t long enough. Around 11am, it occurred to me that I could keep going all day, which surprised precisely no one. Too much reading begets more reading, really, because my brain is tuned to focus and concentration. There was also a prize for most pages read, and I was really hoping for a solid chance at winning it. When I finished reading On Immunity, I read 25 pages of Ducks, Newburyport, and then moved on to my second book of day, Cherie Dimaline’s latest Empire of Wild, and if you’re ever doing a read-a-thon, I’d recommend a book like this. I LOVED IT. Unputdownable. Funny, suspenseful and rich, and yes, it would be a difficult task to follow up her incredibly successful novel The Marrow Thieves, but she’s done it properly here. (I am surprised it didn’t show up on awards lists this fall. With a handful of exceptions, the awards lists have forgotten a lot of the year’s true literary standouts.)

Sunday was a beautiful day, so I spent part of the afternoon outside in my dilapidated hammock, which has only just survived the season and will probably be thrown into the garbage soon, because when I lie in it, my entire weight is being supported by a couple of stitches. But they both held me safe for one more float, as I drank more tea and was enraptured by Empire of Wild. And then there was just an hour left to go. (No! My stamina knows no limits. Who knew that time could past so fast?)

So I read a story by Penelope Fitzgerald, and then 25 more pages of Ducks, Newburyport, and had enough time left to fit in 31 pages of Laura Lippman’s 2011 novel The Most Dangerous Thing, and then it was 3pm. 8 hours were up. Why must we ever stop reading? Why? Why???

Well, because my husband had been taking care of our children all day, and I’d promised to make dinner because he’d done breakfast and lunch, and it really was such a beautiful day that I ought to venture out in before I end up with bedsores. But in the meantime, I’d raised more than $1500.00, with a ton of donations rolling in that morning. (Thank you!!) Cumulatively, the Turning the Page on Cancer campaign raised nearly $22,000.

My #todaysteacup for the read-a-thon was my “Nevertheless, She Persisted” mug, not because I would need to persist through 8 straight hours of reading (turned out to be no chore, guys), but because this is what women happens to women who are diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer, the disease whose research we were fundraising for. There is no cure for metastatic breast cancer, but women diagnosed can go on to live and even thrive for years. The embodiment of nevertheless, she persistedship, with with more research these women can be better supported and live longer, and there will be a whole lot less to “nevertheless” about.

Thanks to everybody who supported me, to the other champions I was reading along with (including my pal Melanie), and to the amazing Samantha Mitchell, who made the whole thing happen. It was so much fun.

October 21, 2019

Gleanings

- Is “A Bargain for Frances” the best book ever written about childhood friendships?

- Why I Had to Rewrite the Ending of My Middle-Grade Book After Charlottesville

- My feet are my locomotive. I walk, a lot.

- I am not going to reproduce or respond to an email that yelled at me, and not in a humorous way, for not blogging often enough.

- Of course, I do believe it, but it’s good to sit with these things or, as the case may be, to blog about these things.

- Still, it was kind of luxurious to spend three days just reading.

- One of the pleasures of being an author is knowing that your characters are out there living their own lives, separate from you, totally out of your control.

Do you like reading good things online and want to make sure you don’t miss a “Gleanings” post? Then sign up to receive “Gleanings” delivered to your inbox each week(ish). And if you’ve read something excellent that you think we ought to check out, share the link in a comment below.

October 17, 2019

Daughters of Silence, by Rebecca Fisseha

Rebecca Fisseha’s novel Daughters of Silence is dazzling, partly because it’s particularly well crafted, but also in the sense that it messes up your vision a bit, that you’re not quite sure what you’re seeing at first. Because the book is a puzzle, a mystery unfolding, and also a circle. I’m so grateful that I had the chance to read it twice, because it’s one of those marvels, a novel that get better and richer with every encounter.

The first time I read it was in the spring in manuscript form after I’d received a message from its editor, who was once my editor, Bethany Gibson, asking if I’d consider blurbing the book. And Gibson’s passion for the novel as so apparent in her message that I agreed without hesitation. I read the novel, and I liked it, the ending in particular. I wrote, “Featuring gorgeous prose and a most compellingly prickly narrator, Fisseha’s debut novel is a puzzle, a page-turner, and a triumph.”

But then I reread the book two weeks ago in anticipation of my conversation with Fisseha at her book launch last weekend, and I wanted to go back to my blurb if only to underline it emphatically at least a million times.

Fisseha comes at her story with a singular, distinctive style, and a character who’s not here to make friends. No, instead Dessie is working to uncover the truth in her own history, the history of her family, truths she’s spent decades unable to face, hiding abuse and trauma in which the people who loved her were partly complicit, and the reader is simply along for the journey, following Dessie as she makes impulsive leaps and takes her own road. Unable to hide from her past anymore, because she’s stuck back in Addis Ababa, her birthplace, after her plane is one of thousands grounded all over the world after the eruption of an Icelandic volcano. Disturbances in the atmosphere, you know, but where the planes can’t fly, Dessie herself manages to discover some clarity, some answers, especially about the experiences of her mother who has recently died and has been buried in Toronto, not back in Ethiopia as had been what was expected.

In her essay for LitHub “on #MeToo in Ethiopia and Eritrea,” Fisseha writes powerfully about what happens when women decide to tell the truth about their own lives: “Perhaps because of my own predisposition to doom and gloom, I had interpreted Rukeyser’s line the world would split open as a disaster scenario. But now I realize how flexible that line is….The world could split open like a flower in bloom, like a woman shattering the glass that had separated her from true connection. Like the global event that became multitudes of habesha women finally telling their stories online…”

The real-life connections to Daughters of Silence do serve to underline the power of story in general, and in this story in particular, but let them not undermine the fact of what a fabulous work of fiction this novel is. The style, remember? The dazzle. Let Rebecca Fisseha take you on a journey. You will be glad you did.

October 15, 2019

Cities Work

I understand the circumstances that have resulted in an increasing number of people on our streets, but what I cannot understand is how someone could walk on by someone who is unconscious on the sidewalk and do nothing, which happens all the time. “If that were me lying on the sidewalk, I’d want someone to help,” I tell my children. “If it were you, I would want someone to help.” Today we called an ambulance for the second time in recent months for someone who was in trouble. Because that guy on the sidewalk, he’s our neighbour. We share this city together, and cities work when we take care of each other.

And as ever, I was so grateful for the kindness of first responders who accorded this man his dignity. Firefighters and ambulance arrived and took care of him, as a Falun Dafa Parade came up the street, an amazing marching band. We’d left by then and were across the street watching the parade half a block from where the firetruck and ambulance were blocking the road, and this tension, these intersections, and connections are why I love cities so much. Why I love this city so much.

It’s a miracle that any of it works, but sometimes it does, and it can be beautiful and so absurd, the golden autumn day a glorious backdrop.

By the time the parade had arrived, the emergency vehicles were gone, the man taken to the hospital, which I know is only the beginning of the story and unlikely to be the end of his struggles. But I hope it helped, and I loved the marching band and their music, and I am so grateful to be connected to all of it, to be part of this messed up, gorgeous, incredible world.