July 20, 2010

People around in the daytime

Nobody works in San Francisco. I noticed this when we were there a few years ago, cafes packed for brunch on a Wednesday morning– “how do these people make a living?” I wondered (“and how can I get to do that too?”). It’s a different kind of culture here in Toronto, where on weekday mornings the sidewalks belong to old men in funny hats, crazy parkbench ladies, and disgruntled nannies pushing double strollers. Or maybe I just frequent the wrong neighbourhoods, but I do know of what I speak, having not only been a stay-at-home mom for the past year, but a graduate student back in not-too-distant history.

Nobody works in San Francisco. I noticed this when we were there a few years ago, cafes packed for brunch on a Wednesday morning– “how do these people make a living?” I wondered (“and how can I get to do that too?”). It’s a different kind of culture here in Toronto, where on weekday mornings the sidewalks belong to old men in funny hats, crazy parkbench ladies, and disgruntled nannies pushing double strollers. Or maybe I just frequent the wrong neighbourhoods, but I do know of what I speak, having not only been a stay-at-home mom for the past year, but a graduate student back in not-too-distant history.

But lately, the days have felt a bit San Franciscan. I made two loaves of strawberry bread last week, because I had visitors due for a string of three afternoons, for a cup of tea or a glass of lemonade, depending on the temperature. Each of them people who are around in the daytime, each of them singularly wonderful (and bearing wonderful things).

On Friday my friend Ivor arrived, who I hadn’t seen properly in far too long, and what he brought with him was Ivor conversation. National newspapers pay him for it (and his twitter followers are legion) but I got the benefit of it directly from my couch, in all its fascinating hilariousness. He let Harriet paw at his iphone. Next up was a most excellent new friend called Kat (we met at the library!) and her fabulous baby boy Atlas, and she showed up with a freaking cheese tray. I think I’m in love with her. And today we had a visit from Julia, who is lovely and brilliant, and brought me At Large and At Small by Anne Fadiman (who I realize now I’ve heard of from a reference on Nathalie’s blog).

Anyway, the point of this being that I’m not sure strawberry bread even begins to account for the riches I’ve recently received. And maybe I can finally stop lusting after San Francisco.

July 19, 2010

Want to get your hands on?

There is no way I can describe to you how much I was enjoying reading CNQ 79 this morning, sipping a splendid cup of tea with the morning breeze drifting in through the window. And not just because it’s the first day in recent memory that nobody local has been operating a sledgehammer or chainsaw outside, nope. It’s because the magazine reads as good as it looks. My favourite kind of writing– critics passionately advocating for the work they love best, and for the short story form in general and particular. Reading the pieces that opened the magazine, I felt so inspired, excited, and lucky to be reading in a time in which, however much the form is maligned, incredible short stories keep getting written. (And celebrated).

There is no way I can describe to you how much I was enjoying reading CNQ 79 this morning, sipping a splendid cup of tea with the morning breeze drifting in through the window. And not just because it’s the first day in recent memory that nobody local has been operating a sledgehammer or chainsaw outside, nope. It’s because the magazine reads as good as it looks. My favourite kind of writing– critics passionately advocating for the work they love best, and for the short story form in general and particular. Reading the pieces that opened the magazine, I felt so inspired, excited, and lucky to be reading in a time in which, however much the form is maligned, incredible short stories keep getting written. (And celebrated).

Due to clerical error, however, I have ended up with two copies of this magazine. If you live in Canada and would like me to mail you my spare, please email me at klclare AT gmail DOT com and tell me the title of your favourite short story. I’ll pick a response at random this weekend. Good luck!

July 18, 2010

Rereading Still Life With Woodpecker by Tom Robbins

I’ll start with the fact that makes me want to die the least (honestly): I used to claim that all the wonderment of literature in general was contained within this one book, and if it was the only book left on earth, all the best things about literature would still remain. I am very glad I never was made to prove this.

I’ll start with the fact that makes me want to die the least (honestly): I used to claim that all the wonderment of literature in general was contained within this one book, and if it was the only book left on earth, all the best things about literature would still remain. I am very glad I never was made to prove this.

And then that I used to have a framed pack of Camel cigarettes hanging on my wall. I believed that it contained all the secrets of the universe, and would inspire me to be the kind of person I wanted to be.

That my copy of this book bears a heartfelt message from a boy who says he loves me. Which is really sweet, unless you know that I encountered him in an internet chatroom one day when I was very bored in 1999, and that we never met. (Though we did used to have discussions about how to make love stay, both agreeing ardently that when the mystery of the connection goes, love goes. However, we never did address how exactly the mystery of connection applies to two people who’ve never met.)

I think I’m less embarrassed about all that, however, than I am about the numerous lines throughout the text that I underlined in purple ink, in particular, “Me? I stand for uncertainty, insecurity, surprise, disorder, unlawfulness, bad taste, fun and things that go boom in the night.” Seriously, why did that speak to me? Because I only ever underlined things in purple ink if they resonated with my deepest being, but no one has ever stood for those things less than I do. Except bad taste. I think maybe it was aspirational…

So there are many ways to begin explaining just how much rereading Still Life With Woodpecker was an exercise in embarrassment. (And I reread this as part of Mark Sampson’s Retro Reading Challenge, I’ll have you know, of which embarrassment was sort of the point, but still, this must be unprecedented) I will explain that when I encountered this book, I was twenty years old and very bored, and that I was just contemplating turning my world upside down for the very first time. (The other line I fervently underlined during this period was from Tom Stoppard’s Arcadia [which I still love] which is: “This is the best time possible to be alive. When everything you know is wrong”).

Still Life… is the story of Leigh-Cheri, an exiled princess/all-American girl (like Anne Hathaway, but with more of a tendency toward unwanted pregnancies) who falls in love with a terrorist (and this was back when terrorism was still homey, domestic and romantic). Bernard is an “outlaw”, outside the law in every sense, except that he gets thrown back in jail, the couple drifts apart, her Arab fiance builds her a pyramid, the couple is reunited, and owe everything to a stick of dynamite. Bernard teaches Leigh-Cheri how to really be free, that love is crazy barking at the moon, that the moon is everything (including birth control), that sometimes you’ve got to throw caution to the wind, and blow a bunch of shit up.

When I read this book the first time, it gave me license to imagine I could live the kind of life I’d imagined. It made me feel more confident about going boldly forth, and making mistakes, and blowing shit up, and breaking the rules, and though I never did any of these things terribly prolifically (apart from the second), I am glad I learned these lessons when I was twenty years old. My life could possibly have been different otherwise, but I am not so sure I owe it as much to the Camel pack as I thought I did.

Rereading this book at 31, I see how far I’ve come, and how my literary judgement has sharpened, because the book is terrible. My political judgement has sharpened also– the Woodpecker is an anti-feminist, libertarian, but I would have noticed neither of these details then. Robbins’ prose is an orgy of play, but his language means nothing beyond its frippery, and it’s not even that funny– the only time I laughed out loud was when somebody sat on a chihuahua. I was bored reading most of it, and so bored out of my head by the end that I was only skimming. The sex was awful and gross, and not remotely sexy. The vagina euphemisms were totally disgusting, and I’m not sure why that didn’t put me off first time through.

I’m glad I reread it though– there were sparks of how brilliant I used to think it was. I don’t know if I’d ever read anything that interesting before, and it might have liberated me as a reader in the same way it did in a more general sense. And I wasn’t wholly cynical about its message. Even now, the idea of having CHOICE guide one’s life is very important to me: “To refuse to passively accept what we’ve been handed by nature or society, but to choose for ourselves. CHOICE. That’s the difference between emptiness and substance, between a life actually lived and a wimpy shadow cast on an office wall.” Rock on Tom!

Kind of inspiring, but not quite worth the 252 pages it took to get there.

July 14, 2010

The News Where You Are by Catherine O’Flynn

Catherine O’Flynn’s two books have been imperfect novels packed solid with goodness. The News Where You Are, like her first novel What Was Lost, chronicles contemporary life in the English Midlands, its bleak dose of “All the lonely people, where do they all come from?” nicely countered with humour, pop culture references, and an underlying faith in the human spirit. Her characters are vividly realized, their dialogue sharp, and the settings evoked with perfect detail. The plots and subplots are absorbing, both novels a pleasure to read, and so in the end all is forgiven even when they don’t quite work as wholes.

Catherine O’Flynn’s two books have been imperfect novels packed solid with goodness. The News Where You Are, like her first novel What Was Lost, chronicles contemporary life in the English Midlands, its bleak dose of “All the lonely people, where do they all come from?” nicely countered with humour, pop culture references, and an underlying faith in the human spirit. Her characters are vividly realized, their dialogue sharp, and the settings evoked with perfect detail. The plots and subplots are absorbing, both novels a pleasure to read, and so in the end all is forgiven even when they don’t quite work as wholes.

At the centre of The News Where You Are is Frank Allcroft, who serves less as a character than as an anchor for the various strands O’Flynn is weaving here– anchor fittingly, because Frank is a local news anchor, O’Flynn depicting the details and minutiae of his job in fascinating detail, and also showing him reflecting on the changing media scene, questioning the place for folksy local in a fast-paced globalized world; Phil Smethway, his old friend and mentor has died six months previously in a mysterious hit and run; Frank is finally beginning to admit to himself how much his mother’s unhappiness has always affected him, and he is also trying to reconcile his feelings regarding his architect father, whose buildings have one-by-one been demolished since his death; Frank makes a point of attending funerals of those whose lonely deaths he reports, and then one of these people turns out to be connected to Phil…

(Frank’s frosty co-anchor, responding to one of his famous corny jokes, asks him, “What the hell am I supposed to do? If I laugh, I look as if I’m mentally ill. If I don’t laugh, I look as if I hate you.” I can’t find another place to fit this in, but I want to repeat it because it’s funny, because it’s a dynamic I’ve never considered, and though a lesser author would make the co-presenter simply hateful and hating, O’Flynn opts more for the more interesting angle. Her characters are always surprising).

It sounds like a hodgepodge, but it isn’t, and in the end the whole thing comes together more effectively than What Was Lost. Too much is going on for this to be a masterful novel, but its strands are all compelling and they comprise the stuff of this world in a way that’s both familiar and surprising. Also a bit shamelessly heartwarming–though its premise(s) are sad, O’Flynn injects enough humour, enough pointed observation about the absurdity of everyday life, and provides Frank with a wonderful family whose solidity is never questioned. Without overdoing it then, O’Flynn gets the bleakness of contemporary England, the centuries of histories underneath the feet, which makes the recent past almost seem disposable, and how “the future” is now something looked back upon with nostalgia. What was lost and what remains.

July 13, 2010

Yes we have some bananas

It’s been more than a month since I last discussed being obsessed with bananas, and so much has happened since then! My quest for banana biodiversity in The Annex turned up plantains in Korea Town, and plantain chips at Sobeys (which tasted just like potato chips, which is sad when plantains are so much better). Eventually, I found baby bananas in Chinatown (and they are sweeter than the Williams Cavendish we’re all accustomed to), and red bananas at WholeFoods (and they even more so, delish). I also learned that banana biodiversity is limited due to more complicated factors than I initially supposed– we don’t find the Gros Michel banana anymore, because they’ve been wiped out by Panana Disease, and other kinds of bananas are pretty much impossible to export.

It’s been more than a month since I last discussed being obsessed with bananas, and so much has happened since then! My quest for banana biodiversity in The Annex turned up plantains in Korea Town, and plantain chips at Sobeys (which tasted just like potato chips, which is sad when plantains are so much better). Eventually, I found baby bananas in Chinatown (and they are sweeter than the Williams Cavendish we’re all accustomed to), and red bananas at WholeFoods (and they even more so, delish). I also learned that banana biodiversity is limited due to more complicated factors than I initially supposed– we don’t find the Gros Michel banana anymore, because they’ve been wiped out by Panana Disease, and other kinds of bananas are pretty much impossible to export.

I read Banana: The Fate of the Fruit that Changed the World by Dan Koeppel, and was relieved to find that the banana obsessed spot the globe. In some countries in Africa, people depend on them for sustenence. North Americans have made them more popular than the apple. In Leuven Belgium, a whole research centre is devoted to preserving the banana, which is under threat due to being a) sterile and b) susceptible to disease. I also learned what it means that the plant is sterile, and how it grows anyway (from clones of itself that come up in the roots). I learned that India is pretty much banana central in terms of biodiversity, but because export is where it’s at banana-wise, local varieties are being pushed out to make room for the Cavendish.

I learned that the Cavendish banana gets its name from a connection to Chatsworth House, now home of the last Mitford sister (and aren’t the Mitfords connected to everything?). What banana republic actually means, and how United Banana (now Chiquita) used its influence to have the US government overthrow the government of Guatamala in the ’50s. The terrible treatment of banana workers, which continues to this day, but companies take no responsibility for because they only sub-contract these workers. That a strain of Panana disease has hit Cavendish plantations in Asia, and if it arrives in North America, bananas are in trouble. That genetic modification is the only way to save the banana, which doesn’t even have the same points against it as most GMO arguments, due to the banana’s unique placement. I want to try the lakatan banana one day.

And now I will copy the recipe for plantain quesidillas which have been rocking my world lately (and it also makes a very good pizza topping). I got the recipe from a handout at the Royal Botanical Gardens in Burlington, and it’s absolutely delicious.

1) In medium frying pan over med-high heat, heat 1 tblespn veg oil. Add 1 plantain coarsely chopped (though I used 2) and saute until golden, about five minutes. Transfer to bowl and set aside.

2) Heat 1 tblespn in saute pan, add 1 med chopped onion and saute until golden, about 4 mins. Add one cap of rinsed black beans, 1/2 cup fresh cilantro (which I never used, subs parsley), 3/4 teaspoon of ground cumin, 1/4 teaspoon of cayenne pepper (which I never used), and saute until mixture is heated, about 5 mins.

3) Mix bean mixture, plantains and 1 cup of grated cheese and, using potato masher, mash mixture until it forms a thick paste.

4) In pan, heat small amount of oil over medium heat. Place one tortilla in pan, spread on bean and plantain mixture, and top with a second tortilla. Heat until bottom tortilla is golden brown and cheese is melting, about 4 mins. Flip and heat reverse side. Remove from heat, cut into wedges and serve with sides of choosing (they recommend sour cream and/or salsa, I never used sides).

July 11, 2010

Rereading Slouching Towards Bethlehem for the fifth time

Rereading Slouching Towards Bethlehem for the fifth time, and it’s full of moments. First, my own moments– cracking the book open for the first time six years ago on a tram enroute to Miyajima, reading it again in 2008 after having been to California, that same rereading and the line from “On Keeping a Notebook”, “because I wanted a baby and did not then have one”, and rereading it again with the baby asleep in her room. It is like keeping a notebook, all the secrets this book holds about who I used to be, and it’s a different journey every time.

Rereading Slouching Towards Bethlehem for the fifth time, and it’s full of moments. First, my own moments– cracking the book open for the first time six years ago on a tram enroute to Miyajima, reading it again in 2008 after having been to California, that same rereading and the line from “On Keeping a Notebook”, “because I wanted a baby and did not then have one”, and rereading it again with the baby asleep in her room. It is like keeping a notebook, all the secrets this book holds about who I used to be, and it’s a different journey every time.

It’s curious that this is a book I can’t stop reading, a book that I long for when we’re parted too long. Because I like novels so very much, but this book of essays speaks to me in a way few novels ever have. Lucille Maxwell Miller and her volkswagen, and the fact of a man called Arthwell Hayton (who went on to marry the au pair, of course). The title essay, and a derailed social movement that Didion puts down to inarticulacy. The way she writes, the repitition and the cadences– her prose is music. Hypnotic. She describes “people of character”, which is a term we hear even less than when she hardly ever heard it anymore. “You see I want to be quite obstinate about insisting that we have no way of knowing– beyond that fundamental loyalty to the social code– what is “right” and what is “wrong”, what is “good” and what is “evil””– which underlines everything she writes, how she appears to just let the pieces fall where they may, her facts and stories speak for themselves, and they do. She’s the most uninstrusive omniscient narrator I’ve ever encountered.

And oh, she’s cool. Her California (you should read her memoir Where I Was From), and her Hawaii, where she is sent to in this book not in lieu of a divorce, but because she was a “recalcitrant thirty-one-year-old child” (as am I!). How she cried in Chinese laundries, and her golden curtains flew out the window and got drenched in the rain, and how the maid sulks when the wind blows (doesn’t she just?). The helicopter dropping the morning paper off on Alcatraz, and how she went to the grocery store in her bikini. And she spins and she spins and she spins– what a master.

I remember reading this book for the first time, and how it was nothing like what I had thought it would be, and how it was harder. To follow the circles of her arguments, to grasp the ungraspable (that things fall apart, the centre cannot hold). I remember how every time I read this book, I discover something new, and how it’s always summer. (“I imagine, in other words, that the notebook is about other people. But of course it is not.”)

July 11, 2010

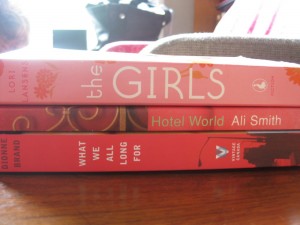

Books I found in a box on Albany Avenue

I swear, the spines aren’t even cracked, and how their hues complement one another. I’m so happy to finally own a copy of The Girls, which I loved so much when I read it a few years ago, and then a book by Ali Smith who I love, but I haven’t read this one yet, and finally What We All Long For by Dionne Brand, which won the Toronto Book Award in 2006. Beautiful. And can you imagine if I’d dared to pass the box by? Five more minutes, and the whole thing would have been drenched with rain.

I swear, the spines aren’t even cracked, and how their hues complement one another. I’m so happy to finally own a copy of The Girls, which I loved so much when I read it a few years ago, and then a book by Ali Smith who I love, but I haven’t read this one yet, and finally What We All Long For by Dionne Brand, which won the Toronto Book Award in 2006. Beautiful. And can you imagine if I’d dared to pass the box by? Five more minutes, and the whole thing would have been drenched with rain.

July 8, 2010

I wish my enemies were Russian

(I wrote this poem a few years ago, back when I wrote poems, and I’m reposting it now, in light of recent events, to celebrate my wish coming true.)

I wish my enemies were Russians

for the privilege of your naivete

they played you like an instrument

set against that Europe

your Russia was a love story;

the thinking man’s erotic fantasy.

You wrote odes to odes on lunacy

but even the polarity was an illusion

shifty spies confused the confusion.

That war was all in your head;

endless scenes of winter

intrigue. Your house with

picture windows and a fallout shelter;

mutually assured destruction.

Your history was the cinematic stuff

of fiction. The enemies were Russians

with beady eyes and edgy names.

Your symbols were comic book

red menaces and red phones,

iron curtains and star wars.

July 8, 2010

I would like to give her more

“It is time for the baby’s birthday party: a white cake, strawberry-marshmallow ice cream, a bottle of champagne saved from another party. In the evening, after she has gone to sleep, I kneel beside the crib and touch her face, where it is pressed against the slats, with mine. She is an open and trusting child, unprepared for and unaccustomed to the ambushses of family life, and perhaps it is just as well that I can offer her little of that life. I would like to give her more. I would like to promise her that she will grow up with a sense of her cousins and of rivers and of her great-grandmother’s teacups, would like to pledge her a picnic on a river with fried chicken and her hair uncombed, would like to give her home for her birthday, but we live differently now and I can promise her nothing like that. I give her a xylophone and a sundress from Madeira, and promise to tell her a funny story.” –Joan Didion, “On Going Home” from Slouching Towards Bethelehem