October 5, 2010

Doomed

All right, used bookshop owners are always a bit strange anyway, so I won’t even start on the woman who, because it was hot that day, couldn’t locate a book she knew was in her stock. Or rather I will start on her, then stop there, and just say that this experience is pretty representative of my efforts to support my local independent bookshops. Where I go out of my way, and spend even more money than elsewhere so that I can help these stores remain in my neighbourhood (because what we would lose if they didn’t), and then the customer service is so absolutely abysmal and I wonder why I bother.

I am fortunate to have independent bookshops all around me where I live, and when I needed a book for our next meeting of the Vicious Circle, I made a point of ordering it from the more-independent bookshop than the other one. I know that ordering a book takes time (which is another problem. Why does it take 2-4 weeks to have a book delivered? As a business model, this totally sucks, and it has to be changed. It just does.), which might be another “why do I even bother?” scenario, but one I was fine with overlooking.

Today I went into the store to see what was going on, and once they finally located my title, I was told that it had been ordered from a distributor that didn’t have the Canadian rights. Somehow it had taken nearly a month to figure out this had happened, no one had gotten in touch with me about it, but they would be happy to place another order from the correct distributor, which would take another 2-4 weeks. Except I need the book on Tuesday, and I was just annoyed by the waste of my time and my effort– I could have had this book from amazon in days at a discounted prize, I could have bought it right off the shelf at Book City. And though I really want to support this other bookstore, why on earth would I ever order another book through them again?

Seriously, if you’re an independent bookshop and you can’t keep *me* as a customer, than there really is no hope for you. And that this doesn’t seem to bother anyone is totally depressing.

October 3, 2010

On reading We Need to Talk About Kevin for the THIRD time

I have determined that Lionel Shriver’s We Need to Talk About Kevin might be one of my all-time favourite books, because I’ve just read it for the third time in five years and devoured it as ravenously as I did the very first. That first time, I was blown away by Shriver’s twist at the end, which I never saw coming and totally stunned me. The second time, I read to discover whether the book would be as good if I knew what would happen, and it was, because I could pay attention to the details that rushed by me and meant little before I knew how things would unfold. This third time, I wanted to read it to see how realized her depiction of motherhood seemed now that I was a mother myself, however the answer to this question wasn’t quite what I came away with.

I have determined that Lionel Shriver’s We Need to Talk About Kevin might be one of my all-time favourite books, because I’ve just read it for the third time in five years and devoured it as ravenously as I did the very first. That first time, I was blown away by Shriver’s twist at the end, which I never saw coming and totally stunned me. The second time, I read to discover whether the book would be as good if I knew what would happen, and it was, because I could pay attention to the details that rushed by me and meant little before I knew how things would unfold. This third time, I wanted to read it to see how realized her depiction of motherhood seemed now that I was a mother myself, however the answer to this question wasn’t quite what I came away with.

What I’ve found most overwhelming about reading We Need to Talk About Kevin this time is what a fascinating narrator Eva is, her very unreliability so unreliable, or perhaps it’s not, which is the point. How this book is always framed in terms of the “issues” it addresses, but in strictly literary terms this is a phenomenal novel.

It’s not about motherhood, or maternal ambivalence, or school shootings. This is a novel about character, and how we present ourselves to the world, how we orchestrate our narratives. Eva being particularly privileged in this respect, as the novel is organized by letters she’s written to her estranged husband, and we have to consider what she chooses to present, to leave out. Does she have less control of the story than she seems too? Are we meant to be so much reading in between the lines, or is this precisely what she might have intended?

As much as the novel is about motherhood, I think it’s more about marriage. And though there is a coldness to Shriver’s novels, she is preoccupied as a writer with intimacy, with the domestic, with the closeness of married life. The dynamics between Eva and her son are far more straightforward than those between Eva and her husband– she presents him as such a doofus, but claims that he’s the love of her life. How could she love such a doofus? Or else, how could she present the man she loves with so little respect? Or maybe that’s just as much as Eva is capable of loving anyone, which puts her back at the centre of the story, the catalyst. Was Franklin the victim of what happened, or was his refusal to acknowledge the problem what only made it worse? She does suggest a framing where he is to blame. Were the family alliances different all along from what they seemed? Or is it just convenient for Eva to have us think this way? By the end of the book, Eva has somewhat redeemed herself as a mother and as a wife, but it’s interesting to question how much such redemption is just her own imposition. The ending she insisted on carving out of this tale.

This is the kind of novel you can come back to over and over again, but it will never just settle down and simply be one thing. It always just escapes one’s grasp. The plot is often boiled down to “nature versus nurture”, but such a simple dichotomy is just the beginning of what goes on. We Need to Talk About Kevin is a multi-headed beast, and I love that about it.

And yes, Shriver’s motherhood is spot-on in many places. As is her distinction between being a good mother and trying to be a good mother, and on the experience of motherhood as transformative or otherwise. I identified with Eva’s experience of failing to bond with her newborn child, which is so much the opposite of everything we’re set up to expect, and though my love grew with time, Kevin the monster baby was not always so far from my reality either. All of this testament to Shriver’s incredible imagination, which is evident in all her novels, as she imagines her way into the wholeness of a character’s life, the intricate details of how they spend their days.

Anyway, third time through it becomes clear to me what a truly “great” work this novel is, and I look forward to returning to it down the line to see what it’s become by then.

October 1, 2010

Two best books I’ve read this year: Mammoth and Light Lifting

Alexander MacLeod’s short story collection Light Lifting never wavers, one solid story after another, and the effect is devastating, gripping, overwhelming. I could hardly believe that the book was this good, and so when I discovered that a friend was reading it at the same time that I was, I got in touch right right away for confirmation. Her take: “This guy is the real thing.”

Alexander MacLeod’s short story collection Light Lifting never wavers, one solid story after another, and the effect is devastating, gripping, overwhelming. I could hardly believe that the book was this good, and so when I discovered that a friend was reading it at the same time that I was, I got in touch right right away for confirmation. Her take: “This guy is the real thing.”

Short stories whose absolutely evoked universes reminded me of Alice Munro in their expansiveness, whose subtly horrifying endings were a bit Flannery O’Connor. Stories so engaged with the stuff of this world, the living and the doing– laying brick driveways, changing an explosive diaper in a disgusting truck stop bathroom, learning to swim, cycling in the snow, crossing the finish line in a track competition, searching for lice, outrunning a train. So vivid that it’s hard to believe it’s fiction, which is why I had trouble remaining composed at the end of the story “Light Lifting”.

These are stories that hinge on a single moment, when one thing turns into another, and yet these single moments are so emblematic of larger stories that each of these stories is a lifetime, is a novel, and utterly satisfying from beginning to end. MacLeod also manages to bridge the literary gender divide, which I found remarkable– how he writes like a woman, and how he writes like a man, and how such distinctions cease to matter with incredible work like this. I am full of awe, amazement, will be foisting this collection on everyone I know, and not a single one of them will be the least bit sorry. They’ll all feel as lucky as I do to have experienced this incredible collection.

(See Light Lifting on the Giller longlist.)

**

Larissa Andrusyshyn’s debut collection of poetry Mammoth is a study in paradox– how death brings the knowlege of what  finally endures; the entire universe made containable by the neat equations of its basest parts; that it is poetry unleashing the magic implicit in algebra, taxonomy, molecular biology, zoology. “Snakes are not made from scratch”, Andrusushyn demonstrates on the basis of its useless hip bone, and so neither are these poems, which have been created from the stuff of life, from the world. The story of the mammoth carcass from which a genome is harvested becomes conflated with another extinction, that of the narrator’s father, and as the scientist diligently searches for what endures, so too does the poet.

finally endures; the entire universe made containable by the neat equations of its basest parts; that it is poetry unleashing the magic implicit in algebra, taxonomy, molecular biology, zoology. “Snakes are not made from scratch”, Andrusushyn demonstrates on the basis of its useless hip bone, and so neither are these poems, which have been created from the stuff of life, from the world. The story of the mammoth carcass from which a genome is harvested becomes conflated with another extinction, that of the narrator’s father, and as the scientist diligently searches for what endures, so too does the poet.

Poems such as “Portrait of the Liver at the Open Mic” use humour to break the body down to its parts, show how these parts both function and decay, and to examine the language we use to understand these processes. “Diagram of Flightless Bird” and “Vestigial” connect these parts of ourselves to what came before us, and posit that we carry all history and the universe within ourselves– that we are not made from scratch either. The mammoth and the father return near the end of the book, the poetry asserting that we do not bury our dead after all. That we are a sum of our parts, of now and all that came before us.

Andrusyshyn’s book is understated and stunning, slim and expansive, hilarious and sad. Thoroughly engaged with a sense of wonder (“Voyageur”) and a sense of play (“The Mammoth Goes to School”). I had such fun reading (and rereading) this collection, and I know I’ll return to it again and discover something new. It’s a book that manages to not only be transporting, but also to deliver us home.

September 30, 2010

Author Interviews @ Pickle Me This: Alison Pick

I met Alison Pick not through literary circles, but because last year she moved in across the street from one of my dearest friends, which was we how ended up attending a babies program at the library together in the depths of winter, and then I happened to run into her one day while I was buying swim diapers at Shoppers Drug Mart. (See, artists are everywhere, out in the world– it’s amazing).

I met Alison Pick not through literary circles, but because last year she moved in across the street from one of my dearest friends, which was we how ended up attending a babies program at the library together in the depths of winter, and then I happened to run into her one day while I was buying swim diapers at Shoppers Drug Mart. (See, artists are everywhere, out in the world– it’s amazing).

I’d read her first novel The Sweet Edge, and many of her reviews in The Globe & Mail, and I was excited to learn she had a second novel coming out. I read Far To Go over a couple of days in August, and loved it, and it was a pleasure to read it once again in preparation for this interview. Alison and I met up over caffeine and sugar a few weeks ago to get our conversation started, and her little daughter was understanding when Harriet broke her tambourine. Our interview proper was conducted via email during the weeks that followed.

I: I am curious about the idea of adherence to facts in fiction, which becomes much more important in a historical novel than a contemporary one. What kind of factual truths were important for you to achieve in Far to Go as opposed to in your previous novel, The Sweet Edge?

AP: Writing Far to Go was different from writing The Sweet Edge in many ways, one of the primary ones being the need to “get it right” historically. There were two kinds of factual truths I was trying to achieve. Firstly, all the little details needed to line up. Street names, makes and models of cars, kitchen appliances, hair styles: I did a lot of googling, I admit, to ensure all of the above were properly situated in time and place. I wanted all of the small details to work in concert to create the second kind of “truth,’ which was an overall sense of historical aliveness. There’s a danger in historical fiction that the research appears too obvious, too self-conscious. I used hundreds of little facts, but tried to blend them into the background so the reader wouldn’t be conscious of them. Like stitches, I wanted the “facts” of my research, in effect, to disappear within the fabric of the narrative.

I: From a writer’s perspective, what is the relationship between historical aliveness and contemporary aliveness? Issues of period aside, do both kinds of literature “come true” in the same essential ways?

AP: Yes, I think that ideally they do, and that the desired goal is to make the one feel like the other. An historical book needs to be grounded in the small details of its own time and place, but the characters and their motivations should feel entirely contemporary.

I: It’s interesting though that in the present day passages of your novel, we don’t see the same attention to specific detail. Part of this, of course, is that your narrator is to be somewhat of a disembodied voice, but we do come to understand her and her environment even without knowing what shade of nail-polish she’s wearing, for example. So what kind of stitches would you say your narrative is constructed of in these parts of the story?

AP: Yes, good point. The present-day narrator is vague around the edges at the beginning of the story and basically remains so for the duration. Of course, I’m trying to conceal her identity for the purpose of narrative tension, hoping the reader will initially think she is the now-grown Pepik, and then, upon discovering her sex, have to revise. And her theorizing is also somewhat in keeping with her vocation – as a professor of Holocaust Studies focused on the Kindertransport she is uniquely situated to offer overall sweeping commentary on its themes (history, memory, dislocation).

Still, though, I did worry that her vagueness would wind up being a weakness, and tried in various revisions to make her more alive by way of nitty-gritty details. It just didn’t seem to work. At least not in any way I was happy with, and in the end I trusted my original intuition that she was meant to be a different kind of character from Pavel, Anneliese, or Marta. In the final pages Lisa acknowledges that she has chosen to withhold the bulk of her own story, fearing that by revealing too many specifics the overall scope might get lost. So, uh, I’m not sure how that translates in terms of fabric and stitches, but if we can switch to paint, her narrative is created with broad strokes rather than detailed brushwork! (more…)

September 30, 2010

On the loss of another great columnist

Dear Mr. Stackhouse [Editor of The Globe & Mail],

I wrote to your paper when you cut your books section down to nearly nothing, and I received a kind reply thanking me for my input. I am sure this message will elicit a similar message, if any, but please do allow me to say how saddened I am that Tabatha Southey will no longer be writing her vibrant, brilliant, relevant, smart and hilarious column in the Saturday Globe. Reading it aloud was a Saturday morning ritual in our family, and between the column’s absence and the now-tiny books section, it’s clear to me that you’re not that interested in me being one of your readers. Which is a shame, because I’ve been a devoted one, who understands the importance of a strong national newspaper, and relishes print for print’s sake. The whole thing makes me very sad, and I think we’re all going to look back on this time in journalism with a great deal of regret. I do already.

Sincerely,

Kerry Clare

[And seriously– no Tabatha Southey & Karen Von Hahn in The Globe, no Katrina Onstad in Chatelaine— these are publications that are killing themselves. It’s totally stupid.)

September 29, 2010

Things in the bag

The following is a list of things in the bag that Harriet carries around the house and cries when we take away from her:

The following is a list of things in the bag that Harriet carries around the house and cries when we take away from her:

1) Two plastic teacups

2) Belinda-Mona’s shoe

3) Harriet’s shoe

4) Whatever socks Harriet is meant to be wearing

5) A can of sardines

6) A plastic saucer

7) A small tin pie-plate

8) A coaster with a picture of the Sargeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album cover on it

9) A pink crayon

10) Conkers

September 28, 2010

When Fenelon Falls

I wrote about my adventures this summer in the land of (almost) no bookshops, and had determined that this area of the Kawartha Lakes region was about as unliterary as they come. And then, this Sunday at the Word on the Street Festival, I discover hot off the Coach House Presses is When Fenelon Falls by Dorothy Ellen Palmer– somehow this unliterary land has generated a book of its own. Having spent about fifteen childhood summers in the vicinity, in addition to a week in August, this book is now a must-read, and though Palmer’s story takes place long before I came along, I am sure some bits will still be quite familiar.

September 28, 2010

On rereading Nikolski

During Canada Reads 2010, I was championing the champion Nikolski, but of course I was a little bit concerned because I’d read the book two years before, and what it if had changed in the meantime? Because books do that, of course, or at least their readers do (which I had to discover with a great deal of nausea once the day I sat down to reread that once-beloved Priscilla Presley autobiography Elvis and Me, but that is another story). So I decided that I would reread Nikolski, to ensure that my championship remains appropriate, and it’s with a great deal of pleasure and relief that I can announce that it has. I will say, however, that it’s not a book that is necessarily better the second time around (as Lionel Shriver’s We Need to Talk About Kevin is, which is why I’ll be reading it for a third time in the next week or so) but it’s just as good, the prose just as rich, the text just as, um, textured. It’s a puzzle of a novel whose pieces fit together absolutely perfectly, the sum of its parts less remarkable than the fact of the summing itself, which is brilliant. In short, Nikolski is a book about books, the spells they cast, the paths they travel, and the paths they set us on.

September 26, 2010

Mad Men is either brilliant or terrible: Update

“Mad Men is either brilliant or terrible,” I wrote a few weeks back, and then last night we watched Season 3 Episode 11 The Gypsy and the Hobo and there’s no doubt it’s the former.

September 26, 2010

Books, I've had a few. Regrets? Not lately.

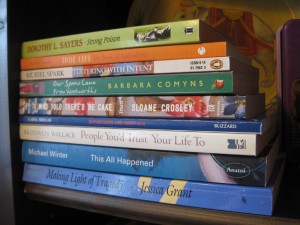

I went out by myself on Saturday m0rning to check out The Victoria College Book Sale (whose half-price Monday is tomorrow, for anyone who’s interested). The plan, seeing as I have far more unread books that I have money, was to purchase a book or two, which was quite a different plan than in years past when I’ve purchased a book or twenty. Plan was also different than in the past, because I was attending on a full-price Saturday, having noticed in the past year or two that the Monday books are usually the same. And am I ever glad that I made the switch, because the books I came home with are absolutely wonderful, albeit slightly more numerous than two. (“But think of all the books I didn’t buy,” I pleaded as I walked in the door, so bookisly laden.)

I went out by myself on Saturday m0rning to check out The Victoria College Book Sale (whose half-price Monday is tomorrow, for anyone who’s interested). The plan, seeing as I have far more unread books that I have money, was to purchase a book or two, which was quite a different plan than in years past when I’ve purchased a book or twenty. Plan was also different than in the past, because I was attending on a full-price Saturday, having noticed in the past year or two that the Monday books are usually the same. And am I ever glad that I made the switch, because the books I came home with are absolutely wonderful, albeit slightly more numerous than two. (“But think of all the books I didn’t buy,” I pleaded as I walked in the door, so bookisly laden.)

Not one of the books I bought is aspirational and due just to collect dust on the shelf, or a book I’m unlikely to enjoy a great deal. I put much thought into my purchases, and just as much into the books I didn’t buy, and I’m happy with what I settled upon. I am extremely excited to dig into each of these.

I got Strong Poison by Dorothy L. Sayers, because it’s the Peter Wimsey novel that introduces Harriet Vane, and I’ve been led to expect fine things from it. I got True Lies by Mariko Tamaki, because she intrigues me and because it was radically mis-catalogued, and so it was fate that I found it at all. Next is Loitering with Intent by Muriel Spark, because reading The Comforters is only the beginning of my Muriel Spark career. Our Spoons Came From Woolworths by Barbara Comyns, which I know nothing about, except that a few other bloggers have read it, I like the title, and I’m fond of that Virago apple. Sloane Crosley I Was Told There Would Be Cake, because I can’t get enough of essays, it comes well-recommended (and there’s cake). Carol Shields’ play Departures and Arrivals, because unread Carol Shields is a precious, precious thing. Bronwen Wallace’s collection People You’d Trust Your Life To, just because it felt like the right book to buy. Michael Winter’s This All Happened because it is shocking that I haven’t read it yet. And finally, Jessica Grant’s collection Making Light of Tragedy, because she wrote Come Thou Tortoise and I’ve heard this book is even better.

Can you believe that discretion was actually exercised? Unbelievable, I know. Less so was exercised today at the Word on the Street Festival, where I purchased a fantastic back issue of The New Quarterly (the quite rare Burning Rock Collective Issue 91), and the Giller-longlisted Lemon by Cordelia Strube. Harriet also got to peek through the Polka Dot Door, and meet Olivia the Pig, and there were also a lot of dogs and balloons, which are two of her favourite things.

In other remarkable this weekend news, someone who was neither Stuart nor me put Harriet to bed last night, because I’d blown the dust off my high heels for our friends Kim and Jon’s wedding. We had the most wonderful time, not least because it was within walking distance (even in said high heels). The ceremony was lovely, the bride was stunning, groom was adoring, the venue was incredible (overlooking Philosopher’s Walk, with a view of the city skyline), great company, delicious dinner, too much wine, and then we got to dance, and had so much fun looking ridiculous. We walked home after midnight happy and holding hands, and I could hardly detect an autumn chill while wearing Stuart’s too-big-for-me jacket.