September 27, 2011

Mini Review: Come Up and See Me Sometime by Erika Krouse

I feel a bit sorry for any book that was published in 2001– that day in September, scores of brand new books would have been made dated immediately, becoming relics of a different time. Perhaps this is part of the reason that Erika Krouse hasn’t published another book since her debut collection Come Up and See Me Sometime, which I bought discarded from the library for a quarter (see? the story of this book was always going to be a tragedy). Her book came into the world when “chick lit” was not so ubiquitous, and still had the potential to be an interesting genre. Her book contained a story called “Too Big To Float” in which a pilot says to his girlfriend, “Go to Aruba with me. I’m flying there tomorrow. It’ll be free. You can sit in the cockpit and see how it’s all done.” A product of another time indeed.

I feel a bit sorry for any book that was published in 2001– that day in September, scores of brand new books would have been made dated immediately, becoming relics of a different time. Perhaps this is part of the reason that Erika Krouse hasn’t published another book since her debut collection Come Up and See Me Sometime, which I bought discarded from the library for a quarter (see? the story of this book was always going to be a tragedy). Her book came into the world when “chick lit” was not so ubiquitous, and still had the potential to be an interesting genre. Her book contained a story called “Too Big To Float” in which a pilot says to his girlfriend, “Go to Aruba with me. I’m flying there tomorrow. It’ll be free. You can sit in the cockpit and see how it’s all done.” A product of another time indeed.

Come Up and See Me Sometime is constructed on a gimmick– each of these stories is preceded by a quote from Mae West. Though I’m no Mae West devotee, the gimmick is superfluous to the stories’ appeal, and I bought this book because it’s about women who choose not to get married, who choose not to have children. It’s about women who make these choices but also don’t necessarily live like adolescents, and I found this approach intriguing. My own reading is drenched in stories of domesticity, and I wanted to broaden my literary horizons a bit.

One never expects to really enjoy a book that was got for a quarter, but it turned out that I received a very good deal. Krouse’s stories are darkly funny, edgy and wise. Impersonators contains the passage, “On Anna’s eighteenth birthday, one of her friends had given her edible underwear. She didn’t go on a single date for over a year. Anna said that eventually she got tired of waiting and ate them herself.” Which is sort of the story of my life.

In “My Weddings” (West quote: “I’m single because I was born that way), a character recounts the weddings she’s attended in her life, and ends with “relief and fear tangled together, like the hands of women clutching in the air for a falling bouquet of something.” In “No Universe”, a woman considers her choice not to have children, and finishes with the most stunning ending, baby with a crackpipe. Romance with an addict is dealt with in “Drugs and You”, in “Other People’s Mothers”, the protagonist gauges her relationship with her mother against the relationships she has had with mothers of friends and boyfriends, in “Impersonators”, a love triangle gone askew involves two office temps who are both so realized.

Come Up and See Me Sometime was a great read, so completely full of promise, and I’d love to know what Erika Krouse, if she’s come out of the cockpit, so to speak, and what her characters would make of this sad new world we’re in today.

September 26, 2011

Author Interviews at Pickle Me This: Jon Klassen

I’m excited to be part of the Jon Klassen blog tour for I Want My Hat Back. At our house, we first discovered Klassen’s work with Cat’s Night Out, which not only won the Governor General’s Award for Illustration, but also received the enormous honour of being our Best Book of Library Haul on July 25th 2011. I also enjoyed his interview at the fabulous kids’ book blog 7 Impossible Things Before Breakfast. Clearly, Klassen is an interesting guy (check out his blog for some proof) and I’d love to know more about the trajectory of his career, why he’s so fixated on oblong shapes, what his own hat looks like (and if he’s ever lost it), but I am not going to ask.

I’m excited to be part of the Jon Klassen blog tour for I Want My Hat Back. At our house, we first discovered Klassen’s work with Cat’s Night Out, which not only won the Governor General’s Award for Illustration, but also received the enormous honour of being our Best Book of Library Haul on July 25th 2011. I also enjoyed his interview at the fabulous kids’ book blog 7 Impossible Things Before Breakfast. Clearly, Klassen is an interesting guy (check out his blog for some proof) and I’d love to know more about the trajectory of his career, why he’s so fixated on oblong shapes, what his own hat looks like (and if he’s ever lost it), but I am not going to ask.

Most of the writers I interview on my blog write chapter books (for adults) instead of picture books,  and I have strong feelings about these interviews focusing on the works themselves rather than their creators, and just because the work in question here is 250 words in length shouldn’t make it an exception. I Want My Hat Back is also good enough that it doesn’t have to be an exception. In these 250 words and the drawings, even with all the understatement in both, there is a whole lot going on, between the lines in particular.

and I have strong feelings about these interviews focusing on the works themselves rather than their creators, and just because the work in question here is 250 words in length shouldn’t make it an exception. I Want My Hat Back is also good enough that it doesn’t have to be an exception. In these 250 words and the drawings, even with all the understatement in both, there is a whole lot going on, between the lines in particular.

Klassen is an Ontario-born illustrator now living in Los Angeles. He was kind enough to answer my questions via email.

I: So, is this a book whose words accompany the drawings, or is it the other way around? Was it from images or words that this story originated? If it was from images, was the story implicit in the pictures, or did you have to go searching for a plot?

JK: I’m not sure it’s either one or the other, as far as what accompanies what. The story came from just the idea of a book with the title “I Want My Hat Back”, and a character on the cover who wasn’t wearing a hat. It was done being written before the pictures, but the writing had the notes about the pictures in it. I wanted a story where the characters didn’t have to do very much physically, so knowing that helped in the writing, but it wasn’t a case of having the characters first and then looking for something for them to do.

I: The bear’s character is rife with contradiction: he has a single-minded fixation upon locating his hat, yet he misses the hat when it’s right before his eyes. When the situation has never been more urgent and he fears never seeing his hat again, his response is to lie down on the ground in despair. When we read him aloud at our house, he speaks in a monotone. How do you read the bear?

I: The bear’s character is rife with contradiction: he has a single-minded fixation upon locating his hat, yet he misses the hat when it’s right before his eyes. When the situation has never been more urgent and he fears never seeing his hat again, his response is to lie down on the ground in despair. When we read him aloud at our house, he speaks in a monotone. How do you read the bear?

JK: I read the whole thing in monotone too. I wanted to try to and make it like the animals were given lines to read off of cue cards. That’s why, at the beginning, the animals are looking at us and not each other. The bear doesn’t see the hat initially because he’s sort of in the play by then and is just waiting for that scene to be done, so he’s not really paying attention. When he realises later what the rabbit has done, it’s like he forgets he’s in the play and becomes a bear again and does what a bear would do if he learned that this had been done to him.

I: I can understand the bear’s limited perspective though. Don’t tell anybody, but the first time I read your book, I completely missed the twist on the last page, the “hat on the rabbit’s head”, to speak in metaphoric terms. One man’s obvious is another man’s subtle, or maybe it depends how fast one man is reading. How do you draw the line? (I’m speaking in metaphoric terms again re. line-drawing)

JK: Keeping that last thing sort of subtle has turned out to be pretty handy when people wonder if the story is too mean for kids. Visually, the problem the book started with is solved at the end, and younger kids, I think, might stop there. That what actually happened is kind of easy to miss sort of saves it for older kids who are reading it to themselves, or are at least paying more attention to the words. I don’t want the book to come off as antagonistic or especially cynical or anything, and I hope that by stashing it away in that last paragraph that we’ve already heard earlier, it gets excused from that.

I: The key to this story’s success is its really simple language, and repetition. Were these a limitation or an aid to you as wrote the story? Similarly with the basic nature of the drawings (ie that the animals are devoid of facial expression). Can limits have an expansive quality?

JK: I think they definitely can. I’d never written a book before, so the formality of narration was really intimidating and I kept feeling  like a fake. When the idea came up of doing the whole thing in dialogue I got a lot more comfortable with it. The stiffness of the language was really the only way I felt comfortable getting the facts across, and the drawings of the animals are kind of the same way. The feeling I wanted to get into the illustrations of them was the same expression you get from a pet that you dress up. They look kind of surprised, they don’t want to move, and they are just generally unimpressed. I think they all have better things they could be doing, but I have this story I want to do, so just hold still for a minute.

like a fake. When the idea came up of doing the whole thing in dialogue I got a lot more comfortable with it. The stiffness of the language was really the only way I felt comfortable getting the facts across, and the drawings of the animals are kind of the same way. The feeling I wanted to get into the illustrations of them was the same expression you get from a pet that you dress up. They look kind of surprised, they don’t want to move, and they are just generally unimpressed. I think they all have better things they could be doing, but I have this story I want to do, so just hold still for a minute.

I: Is this a story about lying? About complacency? About carnivores? About hats? How do you explain it?

JK: I like to think that it’s just a story about itself. It came together so randomly that I can’t really claim a big message. The only abstract idea I had when it was being made was about the rabbit being indifferent, and how threatening indifference can feel. When the bear comes back to him and accuses him of something he’s pretty obviously guilty of, the rabbit doesn’t have a reaction. And when it becomes clearer what the punishment is going to be for this, he still doesn’t really react. He’s silent and unapologetic for this thing he did, and there really isn’t any way you can think of dealing with such indifference. There’s no reasoning with it, so the bear does what he does.

I: Until the story’s conclusion, the bear takes real action just once, when he helps out the turtle and lifts him atop the stone he’s been struggling to climb all day. But then the turtle is stranded there, isn’t he? Isn’t that kind of terrifying? What happens to the turtle??

JK: I think the turtle’s going to be fine. I wanted the bear to do something like that to remind us that even though he’s polite and sad and everything, he is still physically capable of picking most of these guys up off the ground, which is an important thing to keep in mind.

It sounds strange to say given that the turtle only has one line in the book, but I think I “get” him more than most of the other characters in the story, so I’m hoping there will be a book just about him some day.

September 25, 2011

The Vicious Circle reads Lucky Jim by Kingsley Amis

The Vicious Circle rocked The Junction last Thursday night, sitting out on a porch that was deep enough for all of us, on a September night that was warm enough to still be summer (until it got dark, and the chill set in, but it still wasn’t too bad at all). We begin with Kingsley Amis’s Lucky Jim, and the character of Margaret. That she shows Amis’ limitations in creating female characters, and some of us were offended that she turned out to be such a manipulative, conniving minx, though others though her manipulative, connivingness at least showed a bit of agency and made her a less pathetic character (and just as hateful, therefore, as everybody around her). We weren’t sure exactly who she was– she was mousy in her spectacles, though she also flirts with beads and an arty wardrobe. Clearly Margaret is trying it on as much as anybody else is. Though Christine isn’t, or when she is, she’s covering up something more appealing– we note that she’s described as “unmanningly beautiful”, and that she takes on typical male roles in their relationship, and that she threatens him with her strength– we wonder if they’ll actually end up together? Also, we loved Carol Goldsmith, who underlines that Jim, sexually, is still an adolescent.

The Vicious Circle rocked The Junction last Thursday night, sitting out on a porch that was deep enough for all of us, on a September night that was warm enough to still be summer (until it got dark, and the chill set in, but it still wasn’t too bad at all). We begin with Kingsley Amis’s Lucky Jim, and the character of Margaret. That she shows Amis’ limitations in creating female characters, and some of us were offended that she turned out to be such a manipulative, conniving minx, though others though her manipulative, connivingness at least showed a bit of agency and made her a less pathetic character (and just as hateful, therefore, as everybody around her). We weren’t sure exactly who she was– she was mousy in her spectacles, though she also flirts with beads and an arty wardrobe. Clearly Margaret is trying it on as much as anybody else is. Though Christine isn’t, or when she is, she’s covering up something more appealing– we note that she’s described as “unmanningly beautiful”, and that she takes on typical male roles in their relationship, and that she threatens him with her strength– we wonder if they’ll actually end up together? Also, we loved Carol Goldsmith, who underlines that Jim, sexually, is still an adolescent.

We thought the book was hilarious– Dixon’s unfortunate phone calls to Mrs. Welch in particular. Those of us in the know remarked that Amis’s send-up of academia was spot-on. Though we couldn’t figure out if Professor Welch was as dotty as he seemed– was there method to his madness? Was he an older version of Jim? Though we decided that he probably wasn’t because dotty or not, he did have passion for what he did, whereas Jim had passion for nothing.

We talked a lot about class– about how this slapstick comedy works in Britain in a way we’d find much less amusing if it were American.  Jim Carrey as Lucky Jim, somebody noted, would be unbearably horrible, whereas Hugh Grant might be able to pull it off. We wondered why the cultural differences in terms of comedy, and determined that Britain is so firmly entrenched in a class system that there are so many more inviolable rules for characters to transgress. Hence the humour. Though one of us would point out that the American comedy that comes closest is the TV show Curb Your Enthusiasm.

Jim Carrey as Lucky Jim, somebody noted, would be unbearably horrible, whereas Hugh Grant might be able to pull it off. We wondered why the cultural differences in terms of comedy, and determined that Britain is so firmly entrenched in a class system that there are so many more inviolable rules for characters to transgress. Hence the humour. Though one of us would point out that the American comedy that comes closest is the TV show Curb Your Enthusiasm.

So what about class and Lucky Jim Dixon? What’s his background? He only mentions his parents briefly when he laments that he has not parents such as Bertrand Welch’s who’d put him up in a London flat. We learn that the universities are being opened up due to scholarship programs, and this is probably how Jim got there, though it’s pointed out that this expanded population has resulted in a lowered tone. Jim was in the war, was stationed well out of the way of battle up in Scotland, which is typical really for how things go, but it also means he’s never had a chance to prove himself (or be killed with a bullet blast). We thought about him in comparison with Arthur Seaton, a literary contemporary from Alan Sillitoe’s Saturday Night and Sunday Morning— that both characters are locked in where they don’t belong. Then there’s Amis and the angry young men– Sillitoe’s Seaton was a bit of a departure from the other’s though, due to Sillitoe’s own working class origins.

Is class then the focus, that Jim is where he doesn’t belong? That he’s dared to transgress the bounds of his working class origins, and as a result he belongs nowhere. Though what is the class of the other characters, one of us asked? Do they necessarily come from better backgrounds, and it’s suggested that they don’t. That academia is rife with misfits, and Jim is a misfit amongst them, or outside of them, rather.

Is class then the focus, that Jim is where he doesn’t belong? That he’s dared to transgress the bounds of his working class origins, and as a result he belongs nowhere. Though what is the class of the other characters, one of us asked? Do they necessarily come from better backgrounds, and it’s suggested that they don’t. That academia is rife with misfits, and Jim is a misfit amongst them, or outside of them, rather.

Though in Jim’s own words, “I’m afraid that’s a tall order. Explain my conduct; now, that is asking something. I can’t think of anybody who’d be quite equal to that task.” And from this we took that it’s possible to read into this book too much, that it’s really comedy at its heart, one ridiculous action after another, unstoppable once the wheels were in motion. That at his own heart, Jim’s an idiot, a passive and lazy asshole. We wondered about the title because so many unfortunate incidents happen upon Jim that we’re not sure how he could possibly be “lucky”, but he is, and the ending proves it. That he was on the right trajectory from the start: “It was luck you needed all along; with just a little more luck he’d have been able to switch his life to a momentarily adjoining track, a track destined to swing aside at once away from his own.”

Really, then, is this a book about faith?

September 25, 2011

Word on the Street: in the bookmobile!

Though it shames me to say it, we take Word on the Street a bit for granted in our family. Partly because the street in question is ten minutes down the street from our house, and also because we live and breathe books 365 days a year, and so it’s rare that a WOTS vendor can tell me something I don’t know already, or sell me something that I don’t want already. The second point being most important today, as after Eden Mills and the Vic Book sale, I’m all book-bought out. I have too many books, and I’ve spent a lot of money, plus I have a complex about visiting vendors’ booths at WOTS and not buying their wares. So I stayed back from the booths this year, and checked out some readings. Mostly just soaked up the vibe from the bookish crowd, and it was fantastic. We had a wonderful time, and the highlight was the Toronto Public Library Bookmobile, a marriage of Harriet’s two great loves of busses and books. It was the best, best bus we’ve ever boarded, and never has checking out books been more of a novelty. Almost as thrilling as when Harriet would meet Chirp about five minutes later. We had a wonderful afternoon.

Though it shames me to say it, we take Word on the Street a bit for granted in our family. Partly because the street in question is ten minutes down the street from our house, and also because we live and breathe books 365 days a year, and so it’s rare that a WOTS vendor can tell me something I don’t know already, or sell me something that I don’t want already. The second point being most important today, as after Eden Mills and the Vic Book sale, I’m all book-bought out. I have too many books, and I’ve spent a lot of money, plus I have a complex about visiting vendors’ booths at WOTS and not buying their wares. So I stayed back from the booths this year, and checked out some readings. Mostly just soaked up the vibe from the bookish crowd, and it was fantastic. We had a wonderful time, and the highlight was the Toronto Public Library Bookmobile, a marriage of Harriet’s two great loves of busses and books. It was the best, best bus we’ve ever boarded, and never has checking out books been more of a novelty. Almost as thrilling as when Harriet would meet Chirp about five minutes later. We had a wonderful afternoon.

September 24, 2011

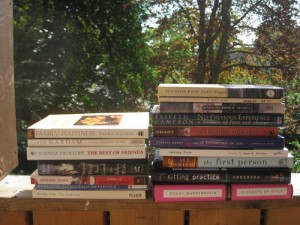

Vic Book Sale 2011

There are not words for how amazing was my haul from this year’s Victoria College Book Sale. Though I did not do as I intended, which was to buy only books from a list of titles I was looking for. From the list, I found one: Barbara Gowdy’s We So Seldom Look on Love, because I’ve never met anyone smart who didn’t revere it. The rest I couldn’t help but pick up alongside it, and I’m so pleased with my selections– I didn’t make the mistake of buying aspirationally, or picking more battered paperbacks condemned to sit unread on my shelf a half-decade.

There are not words for how amazing was my haul from this year’s Victoria College Book Sale. Though I did not do as I intended, which was to buy only books from a list of titles I was looking for. From the list, I found one: Barbara Gowdy’s We So Seldom Look on Love, because I’ve never met anyone smart who didn’t revere it. The rest I couldn’t help but pick up alongside it, and I’m so pleased with my selections– I didn’t make the mistake of buying aspirationally, or picking more battered paperbacks condemned to sit unread on my shelf a half-decade.

The only problem is that I am still determined to get through that unread shelf that I’ve been plowing through for the past six months– they’re in alpha-order by author, and I’ve read up to K so far. And in order for these books to continue to be read, I’ve decided not to read a single one of these delicious new selections until the shelf is empty. Which is a bit torturous, actually, but also very good incentive.

Books got: Family Happiness by Laurie Colwin (which I’ve read already, but has been missing from my library), A Long Way from Verona by Jane Gardam, The Best of Friends by Joanna Trollope, Stupid Boys are Good to Relax With by Susan Swan (I read this when I was in university, and hoping the title might justify my lifestyle at the time), Fables of Brunswick Avenue by Katherine Govier (we don’t live on Brunswick, but we do live about 30 metres from it), Offshore by Penelope Fitzgerald who I am determined to learn to appreciate, The Temporary by Rachel Cusk who is Rachel Cusk after all and I love everything she touches, You Never Know by Isabel Huggan who I’ve never read. I actually wanted The Elizabeth Stories but didn’t find them– have been interested since Elizabeth Hay’s recommendation on Canadian Bookshelf, I got The Rosedale Hoax by Rachel Wyatt which was pubbed by Anansi in 1977 and which I learned about from Amy Lavender Harris’s book Imagining Toronto, Elspeth Cameron’s memoir No Previous Experience, Lynn Coady’s Strange Heaven, Saving Rome by Megan K. Williams which my book club is reading next month, Ali Smith’s collection The First Person, Caroline Adderson’s novel Sitting Practice, and Wendy Wasserstein’s The Elements of Style.

And in about 40-some books’ time, I’ll be permitted to read them!

September 23, 2011

Envelopes by Harriet Russell

As any bookish person would, I spent much of Heather Birrell‘s daughter’s birthday party a few weeks back examining the family bookshelves (while HB led the kids in a round of Pass the Parcel). I was, naturally, interested to discover Harriet Russell‘s book Envelopes, which combines my two great passions of Harriets and the postal system, and the book did not disappoint. Harriet Russell is an artist who came upon the greatest idea ever, which is to send letters to herself with cryptically addressed envelopes requiring a postal worker to solve her puzzles.

As any bookish person would, I spent much of Heather Birrell‘s daughter’s birthday party a few weeks back examining the family bookshelves (while HB led the kids in a round of Pass the Parcel). I was, naturally, interested to discover Harriet Russell‘s book Envelopes, which combines my two great passions of Harriets and the postal system, and the book did not disappoint. Harriet Russell is an artist who came upon the greatest idea ever, which is to send letters to herself with cryptically addressed envelopes requiring a postal worker to solve her puzzles.

As Lynn Truss writes in her foreward to the book, “each envelope… is also a triumph of  humanity– because, after all, in nearly every case, the letter arrived! Therefore a human person must have worked out Harriet’s code, or enjoyed the conceit, or (at the very least) held the envelope at arm’s length, recognising the handiwork of that annoyign woman in that flat on Montague street.”

humanity– because, after all, in nearly every case, the letter arrived! Therefore a human person must have worked out Harriet’s code, or enjoyed the conceit, or (at the very least) held the envelope at arm’s length, recognising the handiwork of that annoyign woman in that flat on Montague street.”

Eventually, the postal workers started writing, “Solved by the Glasgow Mail Centre” on the backs of the envelopes, and their own annotations in the process of solving the puzzles are, as Russell writes, “[now] a real part of the work, adding an extra element that would not be there had they not participated.”

I think my favourite envelope was one made from an old map of London with an X, and the note, “Please deliver here. This is a very old map and the street used to be called Grand Junction.” Also, the drawing of the house with a note reading, “Please deliver to the house pictured”. The address is hidden in a crossword puzzle, connect the dots, colour by number, shopping lists, excerpts from a dictionary, a script from a play, a photograph, a menu, musical notation, and the periodic table of elements. Etc. Etc.

Cover to cover delight.

September 23, 2011

Weaned

At the age of 2 and one quarter and a bit, Harriet is now officially weaned, which I’m telling you now for a couple of reasons. The first is that I truly enjoying horrifying the kind of people who become horrified by the fact that I’ve breastfed for so long. The second reason is because it’s quite a milestone, and I don’t like the idea of breastfeeding having to be a private thing, business that I keep to myself for fear of horrifying somebody (except when I want to horrify someone, as previously noted), because it really is of the mundane essential stuff of life that I write about on my blog all the time. And the third reason I raise the topic here is because breastfeeding was always when I got my periodical reading done, and the loss of this reading time each day now means that I’ve got magazines piling up in my house at a terrifying rate. Plus it’s September, which means there is a new release out basically every day that I’m meaning to getting around to read, and the Victoria College Book Sale is this weekend (which is, as many of you know, the thing I enjoy in the world more than anything else at all except Afternoon Tea). So there will be books, books and more books, and now I’m a bit terrified at the prospect of my leaning tower of magazines.

September 22, 2011

Our Best Book from the library haul: Me… Jane by Patrick McDonnell

Patrick McDonnell’s Me… Jane is the story of an ordinary little girl with a stuffed chimpanzee who just happens to grow up to be Jane Goodall. Significant for being the first biography Harriet’s ever encountered, it also stands up on its own merits as a picture book with delightful illustrations of little Jane getting up to adventures ordinary (sneaking into the hen house to watch hens laying eggs) and extraordinary (Jane imagining herself like Jane from the Tarzan stories swinging on vines through the jungles of Africa). The story awakes its reader to the “magical world full of joy and wonder”, and also tells tells the inspiring story of a little who dared to dream big and whose dreams came true.

Patrick McDonnell’s Me… Jane is the story of an ordinary little girl with a stuffed chimpanzee who just happens to grow up to be Jane Goodall. Significant for being the first biography Harriet’s ever encountered, it also stands up on its own merits as a picture book with delightful illustrations of little Jane getting up to adventures ordinary (sneaking into the hen house to watch hens laying eggs) and extraordinary (Jane imagining herself like Jane from the Tarzan stories swinging on vines through the jungles of Africa). The story awakes its reader to the “magical world full of joy and wonder”, and also tells tells the inspiring story of a little who dared to dream big and whose dreams came true.

In addition to McDonnell’s sweet cartoon rendering of Jane and all the animals, the text pages are enhanced by gorgeous scientific drawings of plants, insects, and other animals. Most remarkable are the samples of Jane Goodall’s own juvenilia, including official documents from a childhood club called “The Aligator Society”.

The end of the book contains a detailed “About Jane Goodall” section and even “A Message from Jane”, which urges that “the life of each one of us matters in the scheme of things”. From even the littlest stories come great things. Or maybe the message is more that even great things have little stories at the heart of them.

September 20, 2011

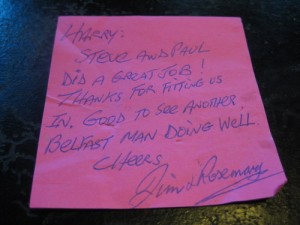

Another Belfast Man Doing Well

I found this on the ground on Saturday, and basically think it’s an entire novel condensed to a post-it note. Who is Harry? What kind of job did Steve and Paul do exactly? (I suspect dry-walling). Is Harry the Belfast man doing well? Can we take this to mean that Jim is a fellow well-doing Belfast man, or is he just someone who collects such people? How much is Rosemary really invested in the situation anyway? What was this note stuck to before it was so carelessly discarded? What’s Harry’s connection to Steve and Paul? And could there be any other names as archetypal as Harry, Steve, Paul, and Jim and Rosemary? Is this note not a throwback to a bygone age? Except for the pink post-it, of course. The pink post-it is very much of now.

I found this on the ground on Saturday, and basically think it’s an entire novel condensed to a post-it note. Who is Harry? What kind of job did Steve and Paul do exactly? (I suspect dry-walling). Is Harry the Belfast man doing well? Can we take this to mean that Jim is a fellow well-doing Belfast man, or is he just someone who collects such people? How much is Rosemary really invested in the situation anyway? What was this note stuck to before it was so carelessly discarded? What’s Harry’s connection to Steve and Paul? And could there be any other names as archetypal as Harry, Steve, Paul, and Jim and Rosemary? Is this note not a throwback to a bygone age? Except for the pink post-it, of course. The pink post-it is very much of now.

September 19, 2011

Cinderella Ate My Daughter by Peggy Orenstein

The bad news about Peggy Orenstein’s Cinderella Ate My Daughter is that she’s preaching to the choir here. My husband and I both read this book, and came away more than ever firmly entrenched that girlie/princess culture is bad news for little girls. And not just because of the limited nature of the princess narrative and her identity, but because underneath it lies the trap of rampant consumerism. The great news, however, is that we can’t afford to join that culture anyway, which also comes with its own parenting challenges, but will make so many other things easier.

The bad news about Peggy Orenstein’s Cinderella Ate My Daughter is that she’s preaching to the choir here. My husband and I both read this book, and came away more than ever firmly entrenched that girlie/princess culture is bad news for little girls. And not just because of the limited nature of the princess narrative and her identity, but because underneath it lies the trap of rampant consumerism. The great news, however, is that we can’t afford to join that culture anyway, which also comes with its own parenting challenges, but will make so many other things easier.

Orenstein does a great job of showing that “princess culture” is such a recent phenomenon, and that signing up is just to play into corporate hands (and to get those hands into your pockets). That these companies are not simply giving consumers what they want, but are also intentionally coercing children into wanting consumer products that are expensive, and detrimental to the development of their self-image. She shows that companies are out to make a buck by gendering children’s toys (thereby ensuring that parents will have to buy two of everything), and also by inventing stages from toddler to tween to “pre-tween” so that nothing ever lasts more than a season.

Orenstein’s writing is funny, engaging, and self-deprecating as she draws on her own experiences as a mother negotiating the labyrinth of princess-dom. She doesn’t take cheap shots, most notably in her chapter on the child beauty pageant circuits. Many of her subjects are really easy targets, but Orenstein writes about them with sympathy, and also shows how their preposterousness is only a magnified version of most parents’ experiences with princess consumer culture, echoing those same old excuses: “But we’re only giving her what she wants” and “It’s doing no harm.” From reading this book, it becomes decidedly clear that neither of these statements are true.

Anyway, what’s strangest to me is that the choir Orenstein is preaching to isn’t all that big. I guess if it was, we’d all have nothing much to sing about. For me, one of the biggest surprises of parenthood all along has been that common sense is such a relative thing. It reminds me of when writer Carrie Snyder wrote about no-gift birthday parties in her parenting column (an idea we’ve since stolen), and got the most cruel (anonymous) responses, similar to those received by Orenstein herself when, as she writes, she first dared to suggest that princess-dom might not be doing our daughters a lot of good. Both mothers were accused of deprivation, which is not so unbelievable, I guess, when you consider that so many people think shoe shopping is exercising our democratic freedom (not to mention, how to be a feminist). Anyway, I guess what I mean is that these are the people who should be reading this book, but they won’t be, and that’s depressing.