October 10, 2011

What Sally Draper must have been reading: Virginia Lee Burton and Mad Men

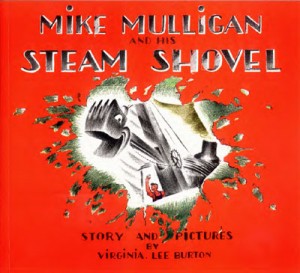

Virginia Lee Burton’s father was an engineer, and her mother was an artist, which is probably a surprise to nobody familiar with her work. Burton’s early books (Choo Choo, Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel, Katy and the Big Snow) are celebrations of man’s power to harness his environment with the use of technology, Burton’s vivid illustrations investing her fascinating machines with life and personality. Even 80 years after the publication of Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel, that steam shovel Mary-Anne appeals to young readers, and part of that timelessness is that Mary-Anne’s story of technological prowess (she could dig as much in a day as a hundred men in a week) was already about nostalgia even when the book was new. Burton’s work does not become dated, because within it she has acknowledged the passage of time. Mary-Anne was already the relic of a dying age, steam shovels being replaced by diesel-powered diggers, and Burton showed even as she glorified technology that progress did not necessarily lead to better.

Virginia Lee Burton’s father was an engineer, and her mother was an artist, which is probably a surprise to nobody familiar with her work. Burton’s early books (Choo Choo, Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel, Katy and the Big Snow) are celebrations of man’s power to harness his environment with the use of technology, Burton’s vivid illustrations investing her fascinating machines with life and personality. Even 80 years after the publication of Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel, that steam shovel Mary-Anne appeals to young readers, and part of that timelessness is that Mary-Anne’s story of technological prowess (she could dig as much in a day as a hundred men in a week) was already about nostalgia even when the book was new. Burton’s work does not become dated, because within it she has acknowledged the passage of time. Mary-Anne was already the relic of a dying age, steam shovels being replaced by diesel-powered diggers, and Burton showed even as she glorified technology that progress did not necessarily lead to better.

But the pastoral age that Mike Mulligan… hearkens back to is a pretty curious one. Children have always loved this book because children are fascinated by machinery and learning how things work (Burton: “Children have an avid appetite for knowledge. They like to learn, provided that the subject matter is presented to them in an interesting way”), but for an adult-reader to understand Mary-Anne as the story’s heroine represents a significant departure from how we in the 21st century have come to understand our relationship to the environment. Mary-Anne who can level hills to make roads for automobiles to drive on, and dig holes to turn grassland into skyscrapers, and is powered by filthy coal– that Burton’s steam shovel continues to be a lovable storybook character is a testament to the enduring qualities of her book as a whole.

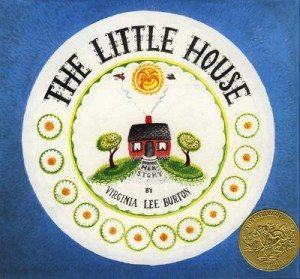

Mike Mulligan was published in 1939, and in 1942, Burton published her most celebrated book, The Little House, which won the  Caldecott Award that year (whose ceremony, it is noted in Barbara Elleman’s fascinating biography Virginia Lee Burton: A Life in Art, was attended by Lillian Smith, president of the Children’s Library Association and head of children’s services at the Toronto Public Library). And from these dates and these books’ acclaim, we can only assume that both found a place within the personal library of Sally Draper, who was born in 1955. Unlike her parents, Sally is rarely seen reading (until Season 4 when she’s spotted with a Nancy Drew), so the contents of her early library can only be inferred, but if the connections between Burton’s world and the Man Men universe are any indication, these books should be an essential part of any Mad Men reading list.

Caldecott Award that year (whose ceremony, it is noted in Barbara Elleman’s fascinating biography Virginia Lee Burton: A Life in Art, was attended by Lillian Smith, president of the Children’s Library Association and head of children’s services at the Toronto Public Library). And from these dates and these books’ acclaim, we can only assume that both found a place within the personal library of Sally Draper, who was born in 1955. Unlike her parents, Sally is rarely seen reading (until Season 4 when she’s spotted with a Nancy Drew), so the contents of her early library can only be inferred, but if the connections between Burton’s world and the Man Men universe are any indication, these books should be an essential part of any Mad Men reading list.

Part of the appeal of both Mike Mulligan and Mad Men is our own nostalgia, but the nostalgia already implicit within these works’ conception of modernity makes our own present ring doubly hollow. In both works, the Future is now, and the present is shining, but something essential has been irrevocably lost, and it has been too late to turn back forever now.

Modernity is symbolized by the city in Mad Men, and also in Burton’s work, no more so than in The Little House. In both works, the city is to be escaped from, its edges a pastoral idyll, though in both works, the city is creeping. In Mad Men, this is shown by suburban life’s failure to be protection enough from the vices and sordidness the city entails. Even in Arcadia (ie Ossining NY), there is infidelity, family violence, divorce, and women lock themselves in the house all day, drinking too much and smashing chairs up. The outside world is brought in every night by the dad in his hat coming home on the train, and by the television’s incessant blare.

Modernity is symbolized by the city in Mad Men, and also in Burton’s work, no more so than in The Little House. In both works, the city is to be escaped from, its edges a pastoral idyll, though in both works, the city is creeping. In Mad Men, this is shown by suburban life’s failure to be protection enough from the vices and sordidness the city entails. Even in Arcadia (ie Ossining NY), there is infidelity, family violence, divorce, and women lock themselves in the house all day, drinking too much and smashing chairs up. The outside world is brought in every night by the dad in his hat coming home on the train, and by the television’s incessant blare.

The creeping is literalised in Burton’s The Little House, which sits contentedly on its hill as the sun goes up and down, and as the seasons change. And then the lights of the city began to seem closer, and roads appear (courtesy of that same steam shovel we know so well from Mike Mulligan, as Harriet is always delighted to point out). There are new houses, and then the buildings around the house grow higher, and a subway is dug underneath, and trams run back and forth, and eventually the house is left abandoned and unloved in the middle of an urban wasteland. (And in this book, indeed, Burton has presaged and synthesized the ideas of Rachel Carson and Jane Jacobs).

But the book’s conclusion is as curious as is Mary-Anne’s status as hero instead of villain. The story of The Little House is resolved when a great-great grandaughter of the man who’d built the house discovers the place in its derelict state, and decides to move it back out to the countryside. Traffic is halted as the house is lifted up from its foundations and placed on a truck, then driven down a big road, then a small road, and eventually the house is settled down on a little hill much like the one it once called home (before that first hill was levelled by a steam shovel). Same apple trees and flowers, and the house can see the sky again, the sunrise in the morning, the moon shining high at night. “The stars twinkled all around her…/ A new moon was coming up…/ It was Spring…/ and all was quiet and peaceful in the country.”

The first few times I read this book as an adult, I figured the moral had something to do with white flight, and the death and death of the  American city. Until I realized that Burton hadn’t presaged Carson/Jacobs so much, and then I thought about the book in the context of its own time, and Mad Men’s. The story’s point, according to Elleman’s book, is that “the further away we get from nature and the simple way of life the less happy we are.” It is a story of the environment with man still at its centre, and with this notion of the city as a place to move away from is an understanding that the space “away out there” is infinite, inexhaustible. (See Kathryn Davis’s Hell and the spaces at the back of medicine cabinets for razor blade disposal in the mid 20th century house– that throwing something “away” was to make it disappear.)

American city. Until I realized that Burton hadn’t presaged Carson/Jacobs so much, and then I thought about the book in the context of its own time, and Mad Men’s. The story’s point, according to Elleman’s book, is that “the further away we get from nature and the simple way of life the less happy we are.” It is a story of the environment with man still at its centre, and with this notion of the city as a place to move away from is an understanding that the space “away out there” is infinite, inexhaustible. (See Kathryn Davis’s Hell and the spaces at the back of medicine cabinets for razor blade disposal in the mid 20th century house– that throwing something “away” was to make it disappear.)

In “The Gold Violin” (Mad Men, Season 2), the Drapers retreat further from urban/suburban life by partaking in a rare family outing, a picnic (although they get there in a brand new Cadillac, so modernity has certainly not been left behind). At the end of the picnic (which has involved smoking while horizontal and peeing behind trees), Betty Draper picks up the picnic blanket and shakes away accumulated rubbish, letting it fall down onto the grass where she’ll leave it.

As in Burton’s The Little House, the world away out there is still ours for the taking, to be used and made noble by our relationship to it.

October 7, 2011

The Withdrawal Method

I knew we were in for trouble once I’d spent most of Monday in tears about the death of Ralph Steinman, co-winner of the Nobel Prize for Physiology. For the next few days, emotions and hormones conspired to make me insane, and were assisted by my having read Lois Lowry’s The Giver and then Tessa McWatt’s Vital Signs, two very different books who share much heaviness in common. By the time I started reading Pasha Malla’s The Withdrawal Method on Wednesday, things were out of control. “Everybody’s dying of cancer in this book,” I kept exclaiming. “I thought Pasha Malla was supposed to be funny.” (Interestingly, reading McWatt followed by Malla was sort of fascinating, if not depressing. Both books share surprising things in common beyond their pictograms, Malla’s first story, “The Slough” in particular.) I wasn’t sure I’d be able to take much more of it, but was urged onwards at a gathering of Pasha Malla devotees on Wednesday night, which was operating under the guise of a reading by Rebecca Rosenblum and Laura Boudreau at Type Books. The Pasha Malla thing I discovered once I’d started railing against The Withdrawal Method in the cookbook section, and was confronted by a league of passionate defenders. Sympathetic passionate defenders, mind you. They understood about the Ralph Steinman thing and that I was operating under a limited emotional capacity at the moment. That perhaps this wasn’t the book for everyone, at every time. And I understood that it was a bit like back in my first trimester of pregnancy when I hated every single book that came my way because I associated all of them with feeling nauseous and exhausted, except that now, of course, I’m the opposite of pregnant.

I knew we were in for trouble once I’d spent most of Monday in tears about the death of Ralph Steinman, co-winner of the Nobel Prize for Physiology. For the next few days, emotions and hormones conspired to make me insane, and were assisted by my having read Lois Lowry’s The Giver and then Tessa McWatt’s Vital Signs, two very different books who share much heaviness in common. By the time I started reading Pasha Malla’s The Withdrawal Method on Wednesday, things were out of control. “Everybody’s dying of cancer in this book,” I kept exclaiming. “I thought Pasha Malla was supposed to be funny.” (Interestingly, reading McWatt followed by Malla was sort of fascinating, if not depressing. Both books share surprising things in common beyond their pictograms, Malla’s first story, “The Slough” in particular.) I wasn’t sure I’d be able to take much more of it, but was urged onwards at a gathering of Pasha Malla devotees on Wednesday night, which was operating under the guise of a reading by Rebecca Rosenblum and Laura Boudreau at Type Books. The Pasha Malla thing I discovered once I’d started railing against The Withdrawal Method in the cookbook section, and was confronted by a league of passionate defenders. Sympathetic passionate defenders, mind you. They understood about the Ralph Steinman thing and that I was operating under a limited emotional capacity at the moment. That perhaps this wasn’t the book for everyone, at every time. And I understood that it was a bit like back in my first trimester of pregnancy when I hated every single book that came my way because I associated all of them with feeling nauseous and exhausted, except that now, of course, I’m the opposite of pregnant.

Anyway, I woke up yesterday feeling much less idiotic, and continued on with The Withdrawal Method, and appreciated it more than I’d ever thought possible on Wednesday. Am convinced that this all really does have something to do with the second half of the book being better than the first, but perhaps that’s just my idiot bias showing. Regardless, I’m following it up with novel by Jennifer Weiner, which is the sort of thing I need right now like I really need a hot bath and a bar of chocolate.

October 6, 2011

Our Best Book from the Library Haul: Russell Hoban's A Birthday for Frances

It’s probably only been a month since we became acquainted with Russell Hoban’s Frances books, but I feel like she’s been a part of our lives forever. She was fast beloved, and my only complaint is that some of her books are a little bit long, which is a problem, you see, because I never end up reading one less than three times in a row. Harriet’s attention rarely wanders, however, and I think we’ve found our favourite Frances yet with A Birthday for Frances. The story of an older sister (who just happens to be a badger) upset with the attention being paid to little sister Gloria who’s on the verge of turning two. I love the Frances books because Frances really battles her demons, her worst self, and she shows that doing the right thing is so hard (and more over, she doesn’t even always do the right thing). For a badger, she’s one of the most realistically drawn, complex characters I’ve ever encountered in a picture book.

It’s probably only been a month since we became acquainted with Russell Hoban’s Frances books, but I feel like she’s been a part of our lives forever. She was fast beloved, and my only complaint is that some of her books are a little bit long, which is a problem, you see, because I never end up reading one less than three times in a row. Harriet’s attention rarely wanders, however, and I think we’ve found our favourite Frances yet with A Birthday for Frances. The story of an older sister (who just happens to be a badger) upset with the attention being paid to little sister Gloria who’s on the verge of turning two. I love the Frances books because Frances really battles her demons, her worst self, and she shows that doing the right thing is so hard (and more over, she doesn’t even always do the right thing). For a badger, she’s one of the most realistically drawn, complex characters I’ve ever encountered in a picture book.

Love this book also for the marvelous prose as Frances sets the scene for an imaginary frend called Alice: “That is how it is, Alice,” said Frances. “Your birthday is always the one that is not now.” Or when she’s reluctantly drawn into making place cards for Gloria’s birthday table, and sings: “A rainbow and a happy tree/ Are not for Alice or for me./ I will draw three-legged cats./ And caterpillars with ugly hats.”

I love the way Hoban acknowledges the dark side of a child’s emotional life, reflecting and validating feelings of jealousy and anger. And how the story shows its readers how to work through these feelings, but is also resolved in a way most marvelously un-saccharine.

*Turns out Russell Hoban is a sci-fi, fantasy novelist. Though there is no sign of this in the Frances books, it’s not all that surprising either.

October 5, 2011

Vital Signs by Tessa McWatt

Tessa McWatt writes the strangest novels. I’d read Step Closer in 2009, and found it utterly puzzling; not perfect, but so unlike anything else I was reading at the time that it struck a chord and stayed with me, the way she experimented with narrative and form to challenge the limits of fiction and story. Her latest novel Vital Signs is just as odd, and just as much a puzzle. It begins with a husband whose wife is wearing an electrode cap, having her brain scanned, and it dawns on him that he is not worthy of her. And we are to take from this that the idea has never occurred to him before the novel’s first sentence, that in all the years underlying this novel’s relatively brief time span, that he’d never considered this dynamic. But it’s hard to take him at his word, because he’s a narrator who doesn’t even know his own story, let alone his own self.

Tessa McWatt writes the strangest novels. I’d read Step Closer in 2009, and found it utterly puzzling; not perfect, but so unlike anything else I was reading at the time that it struck a chord and stayed with me, the way she experimented with narrative and form to challenge the limits of fiction and story. Her latest novel Vital Signs is just as odd, and just as much a puzzle. It begins with a husband whose wife is wearing an electrode cap, having her brain scanned, and it dawns on him that he is not worthy of her. And we are to take from this that the idea has never occurred to him before the novel’s first sentence, that in all the years underlying this novel’s relatively brief time span, that he’d never considered this dynamic. But it’s hard to take him at his word, because he’s a narrator who doesn’t even know his own story, let alone his own self.

Michael is the kind of husband who’s always loved his wife best at a kind of distance. (I’d mentioned that McWatt’s previous book reminded me of Emily Perkins’ Novel About My Wife. It ain’t got nothing on how this one does.) He’s attracted by the darkness of her skin when he first meets her, and waits for weeks to discover where she actually comes from, because he prefers the allure of mystery. An allure that is all but extinguished when his exotic wife is transferred to a domestic setting, and sets to work keeping his house and rearing his children. Michael’s disappointment is only added to when his design career doesn’t take off as he expected, and though he does well enough, so many dreams remain unrealized. His desperation for more finds an outlet in a cliched affair with a young colleague, which ends after too many years of her wanting more than he can give.

When Michael’s wife Anna is diagnosed with an aneurysm, the history of his marriage becomes stirred up in the present. He knows there is a chance his wife could die, and he is anxious to confess his sins to her. But this is complicated by Anna’s medical problems, which have left her with a mangled, near-indecipherable way of communicating. The words themselves are clear, but put together, they are nonsense, or else they are stories of things she believes are true that have actually never happened.

And yet, Michael feels there is secret meaning to what she says, that she knows more than she lets on. He begins to find himself communicating with her better than he has in years, and he uses his own skills in designing pictograms to tell her things he’s never been able to put into words. The reader finds, however, that he’s really just slipping into the same old patterns, lusting after his wife when she is away from him, exoticizing her character. He imagines the dressings that will be wrapped around her head after brain surgery: “[the nurse] will wrap it once, twice, more times around Anna’s head, and my wife will resemble an Egyptian nomad.”

Puzzles aside (and there are plenty. McWatt is attempting to answer the question, “What is a mind?” after all. The novel contains actual representations of Michael’s pictograms, and I confess to poring over the novel’s ending and still not really understanding what happened. Though perhaps this is the point– that Anna gets it, and this is all that matters), this is a novel about marriage and family. A decidedly bleak novel about marriage and family, and Michael’s ambivalence toward his wife and children pointedly demonstrates the desperate underside of love.

October 3, 2011

Caspian really loves his books

First, I have noticed the way that all parents says things like, “Caspian really loves his books. He just can’t get enough off them. He turns the pages, and loves the pictures, and chews on the spine, and laughs at the funny bits.” I’ve heard this kind of bragging so often that I think book-loving must be a thing that most little kids just do, like crawling and growing teeth. My daughter really loves her books too, and it’s one of the most delightful things about her, but maybe this is just one of the things we can take for granted when we’re fortunate enough to be literate, and have a love of books to share.

First, I have noticed the way that all parents says things like, “Caspian really loves his books. He just can’t get enough off them. He turns the pages, and loves the pictures, and chews on the spine, and laughs at the funny bits.” I’ve heard this kind of bragging so often that I think book-loving must be a thing that most little kids just do, like crawling and growing teeth. My daughter really loves her books too, and it’s one of the most delightful things about her, but maybe this is just one of the things we can take for granted when we’re fortunate enough to be literate, and have a love of books to share.

Second, I can’t believe I once wrote here in awe of such things as, Harriet can actually wave (without prompting, even!), and I’m sure that if we go back far enough, I wrote about how thrilling it was when she could finally hold her head up. Blah blah blah. And so I hope that myself a few years down the line will forgive me for posting the following (and that all of you with older children who know how boring and ubiquitous such things actually are will humour me for a moment): yesterday, Harriet read me a book. Yesterday, Harriet flipped through the pages of Olivia and the Missing Toy and more or less told me the story, beginning with, “One day, Olivia was riding a camel through Egypt…” In her funny little goblin voice, and Olivia is called Owivia. Some of the text is hard to decipher, but I like that she never forgets the pages on which Olivia’s mother calls her, “Sweetie Pie”. Being read a story by Harriet was really one of the greatest experiences of my life.

Harriet reading in bed. Yes, she still has a soother and sleeps in a crib. Do you want to make something of it?*

We do live a bookish life, reading our favourites over and over. We get about 15 books from the library every week, which mixes things up a bit. For some reason, we keep getting books about wolves though, over and over. Harriet keeps telling us things like, “The big bad wolf is in my room,” and then informs us that, “he’s teeny tiny.” Today she cried because we didn’t get a Katie Morag book from the library, and so we had to go back. (Actually, today was kind of annoying, but that’s another story…) Lately, she loves Little Bear, Charlie and Lola, Elephant and Piggie, Alfie and Annie Rose, Stella and Sam, Arthur and Franklin. Also Curious George, whose books are so long that reading them over and over gets to be a little tiresome. Don’t tell anyone I said so.

It’s Children’s Book Week this week at Canadian Bookshelf. First post went up today about the TD Grade One Giveaway, which is quite a cool program. Check the blog for new posts all week, including great ones by Sheree Fitch and Kristen den Hartog.

*”Do you want to make something of it?” is actually a quote from Judy Blume’s Superfudge, as delivered by Fudge’s best friend Daniel Menheim. As in, “I’m Daniel Manheim. I’m six. I live at 432 Vine Street. You want to make something of it?” Superfudge may be the only cultural reference point I allude to as often as Wayne’s World.

October 2, 2011

Outside the Box by Maria Meindl

My friend Maria Meindl has written one of the best books I’ve read this year in Outside the Box: The Life and Legacy of Writer Mona Gould, The Grandmother I Thought I Knew, and it’s a book that proves fascinating on all different kinds of levels. First, Meindl’s book is a history of magazines and radio broadcasting in Canada during the mid-2oth century, demonstrated by the experiences of Mona Gould who made her entire career as a freelancer in poetry, copy-writing, feature-writing, radio broadcasting, and column-writing between the 1930s and the 1960s. She wrote for publications including Saturday Night and Chatelaine, worked as a publicist for the Red Cross during WWII, was affected by the split between commercial and literary writing that took place during the 1950s, published two books of poetry, and her most famous poem “That Was My Brother” in included in anthologies and textbooks to this day. In her radio broadcasts, she’d have to find subtle ways to work word of her program’s sponsor into her scripts. At times, Gould was published in the same periodicals as poets as notable as PK Page and Margaret Avison, but never achieved the same prominence herself, and from this failure to remarkably ascend, her story has a great deal more to tell about the wider world of publishing and broadcasting in her time than those of those whose experiences were so singular.

My friend Maria Meindl has written one of the best books I’ve read this year in Outside the Box: The Life and Legacy of Writer Mona Gould, The Grandmother I Thought I Knew, and it’s a book that proves fascinating on all different kinds of levels. First, Meindl’s book is a history of magazines and radio broadcasting in Canada during the mid-2oth century, demonstrated by the experiences of Mona Gould who made her entire career as a freelancer in poetry, copy-writing, feature-writing, radio broadcasting, and column-writing between the 1930s and the 1960s. She wrote for publications including Saturday Night and Chatelaine, worked as a publicist for the Red Cross during WWII, was affected by the split between commercial and literary writing that took place during the 1950s, published two books of poetry, and her most famous poem “That Was My Brother” in included in anthologies and textbooks to this day. In her radio broadcasts, she’d have to find subtle ways to work word of her program’s sponsor into her scripts. At times, Gould was published in the same periodicals as poets as notable as PK Page and Margaret Avison, but never achieved the same prominence herself, and from this failure to remarkably ascend, her story has a great deal more to tell about the wider world of publishing and broadcasting in her time than those of those whose experiences were so singular.

Which is not to say that Mona Gould was not remarkable or singular. At her best and worst, there was no one else quite like her, and Meindl has done a tremendous job of portraying such a complicated woman and the ambivalence involved in family relationships. Though she certainly had the resources at her disposal– Outside the Box is not just Mona’s story, but is also the story of Maria’s years-long efforts to catalogue Mona’s archives for the Thomas Fisher Library at the University of Toronto. Boxes upon boxes she’d inherited after her grandmother’s death, and she writes about how the boxes were conspicuous in the archives– everything slung into boxes willy-nilly, the boxes themselves tatted and from anywhere, and the papers within covered with dust and cat-hair, and she’d discover open tubs of vaseline, and on the back of one pile of of papers was stuck a colostomy bag. The boxes were a mess, and cataloguing them often appeared an impossible task. More burden than gift, as her grandmother had so often seemed to be to Maria. And yet there was richness to be found, and a Mona Gould to be discovered who was distinct from the alcoholic, mean-spirited woman she remembered as having come between her parents in their marriage. Letters written to lifelong friends, papers that demonstrated that Mona had worked hard for her success and it had not simply appeared to her, as she sometimes spun it. That this woman who put herself above feminism and craved approval from men had battled discrimination throughout her career. Maria had been aware that her grandmother had been something of a liar, but the truth behind these stories is often more fascinating than she’d ever imagined.

The book also has much to say to a society so fixated on the cult of personality, celebrity, which Meindl shows is not an altogether modern phenomenon. It is likely that Mona Gould worked as hard on cultivating her “brand” as she did her writing (though, obviously, she would not have put it that way), craving attention and admiration, and in the end, she’d prove a victim of society’s fickleness, and to the changingness of fashion.

Ultimately, however, Outside the Box is a story of inheritance, of coming to terms with where we’ve come from and who we are. In exquisite prose and with a fascinating mastery of chronology, Meindl makes this her own story as much as Mona’s, the story of how becoming settled in her own life and happiness required her to make peace with her family’s past, to unpack the metaphoric baggage that was as heavy as all those boxes and boxes her grandmother had left her.

October 2, 2011

What's the point of being a sell-out if you're not getting paid?

I have never, ever blogged for free. Well, except for the times I did, here and elsewhere, but it’s different, and I will tell you why. But first, I want to underline how much I appreciated Russell Smith’s column last week about his bafflement with young writers who have no qualms with slinging words for nothing. Writers, I suppose, like me, who’ve spent the last decade slapping my life up online: “Ever since they were teenagers, they had clever thoughts, they posted them online, people reacted immediately… They can get famous fast this way, and it’s gratifying to have a huge audience.” (Or a tiny audience, or any audience at all. Hi Mom!)

I appreciated Smith’s article because it’s good to have occasion to step back and question the absurdities of one’s own life. And also because I think he’s right, in particular in the case of online magazines like the Huffington Post, “the cash-cow possession of a giant media conglomerate. There is no question that the HuffPo can afford to pay, and pay well.” And I’m sure he’s right, because when I blogged for the literary journal Descant from 2007-2009, they could afford to pay me. Not a whole lot, no, but no one pays me a whole lot for anything I do. But no one who pays me has a whole lot either, and I have even less, so it actually comes to be not insubstantial in the end. (And isn’t that the great thing about living on little– it doesn’t take much to make you feel rich.)

Anyway, my experiences have actually been the fulfilment of what Smith so scathingly rebukes. Though I promise you that I’ve never given a thought to my “brand” (because such a thought, I think, would undermine the fact that I’m a person), much of my writing career has come about as an extension of the work I’ve done for free. Indeed, it’s paid off pretty well. (I used to have this theory that perhaps I’d done okay because I was a person instead of a brand, but then I discovered there exists this wildly popular circuit of bloggers who do nothing but go to parties and wear ridiculous shoes, and realized that beating hearts, in fact, count for little.)

But I am sure that I have had some success as a blogging writer precisely because success as never been my primary objective. (This is going to be a discussion we return to many times in my blogging course, which starts on Tuesday. [I realize now this looks like product placement. It isn’t. I’m just excited, and have blogs on my mind].) When I stared blogging, no one did it to attain anything, except maybe a weird boyfriend on the other side of the country who looked like a hobbit. I’ve blogged for so long because I like the platform, yes, but mostly my blog has been useful to me in all manner of ways beyond that– my blog is a record, an infinitely valuable catalogue of memories, it has made me into a better writer and a better reader, it has allowed me to tap into communities of readers and writers who’ve become my friends (some in my neighbourhood, even!), it has allowed me to write rambling pieces (ie this one) that develop my ideas and has clarified my world, and it’s also a fine way to keep in touch with friends and family near and far. If no one was reading my blog, I would still be doing it.

But of course it’s a minefield, trying to answer these questions of why do we blog exactly. A less nice way to phrase what I wrote in the preceding paragraph is that blogging is inherently self-indulgent. Of course, I like getting positive attention. But I really do like to think that I’m serving the books I read, the authors who wrote them, and their readers. For me, it always come back to the Virginia Woolf quote: “The standards we raise and the judgements we pass steal into the air and become part of the atmosphere which writers breathe as they work.”

Last week, I read another article about blogging, this one about women bloggers who wield enormous influence, and are paid in consumer goods by companies who are hungry for some online attention. These women appear to be more frustrated with the system than Russell Smith’s bloggers, but it’s remarkable to me how much these women are corporate slaves as much as the HuffPo bloggers are, how much blogging has come to have everything to do with furthering corporate interests and making people spend more money on shit. It seems remarkable how many bloggers are compromising their integrity to be courted by corporations who really don’t seem to make the best suitors– I mean, what’s the point of being a sell-out if you’re not getting paid?

This isn’t blogging as I’ve come to know it. These women are doing it wrong.

And yet. I mean, I’ve got my own corporate relationships here. For years, publishers have been sending me books for review, and this has been something it has been tough for me to negotiate. Initially, I was pretty bad at it. Initially, I thought these publicists were doing me a favour, and this is probably reflected in a review or two in which I went a little too easy. I didn’t understand that our relationships were actually reciprocal, and I’ve slowly figured it out, I think. That I’ve got to keep buying books in order to exercise my power as a consumer and my independence as a reader, and that I’m allowed to criticize the books that come my way, and that I deserve to be taken seriously as a reader and reviewer (but I’m not to be an asshole about it. I’m a blogger after all. I get that too.). I claim the right not read certain books, and to stake out my territory as a reader– it amazes me to see bloggers reading totally out of their comfort zones because a publicist “was kind enough” to send a book that didn’t suit them. I guarantee you the publicist was less kind than kind of lazy.

But I also appreciate the publicists who do take the time to highlight books that are up my alley, and who care about good books as much as I do. I like to think there is an important distinction between books and the vast amount of unnecessary crap that mothering blogs, or gadget blogs, and the advertisements accompanying both are always trying to convince you that you need. The difference is that books aren’t stuff, they’re culture, and when book bloggers are doing their jobs right, that culture is enriched.

September 29, 2011

Time for some Harriet

The day Harriet learned about Katrina and the Waves, and also Miss Mabel Murple visits Dutch Dreams.

September 29, 2011

Our Best Book from this week's library haul: Wolves by Emily Gravett

We love Emily Gravett at our house– Monkey and Me, Orange Pear Apple Bear, Meerkat Mail, Dogs, Spells— but her Wolves was never on the library shelf, though I looked for it week after week. Turns out because it was on the older readers library shelf, probably because it’s another book in which a rabbit gets devoured (hi Jon Klassen! Don’t worry. You’re all working in the Beatrix Potter tradition. Everything will be fine…). We read it a few times, then Harriet decided it would join the realm of “too scary”, but then we got the new Chirp in the mail, which does a profile of wolves including baby ones (this is key. No such thing as a scary baby), and so now we love wolves and Wolves, and Emily Gravett’s good book is back in ours.

We love Emily Gravett at our house– Monkey and Me, Orange Pear Apple Bear, Meerkat Mail, Dogs, Spells— but her Wolves was never on the library shelf, though I looked for it week after week. Turns out because it was on the older readers library shelf, probably because it’s another book in which a rabbit gets devoured (hi Jon Klassen! Don’t worry. You’re all working in the Beatrix Potter tradition. Everything will be fine…). We read it a few times, then Harriet decided it would join the realm of “too scary”, but then we got the new Chirp in the mail, which does a profile of wolves including baby ones (this is key. No such thing as a scary baby), and so now we love wolves and Wolves, and Emily Gravett’s good book is back in ours.

The poor bunny (who’s not so innocent, I think. Surely, he’s a hat thief) takes a book out of the library to learn about wolves (and Gravett gives us an images of the end papers from the rabbit’s book with the date-due slip and the checkout card that actually comes out of the book, and even though ours is a library book (yes, a library book with a library book inside it– trippy), nobody’s lost it yet– magic!). He’s got his nose in the book through the rest of this book, making the mistake that’s as old as literacy, thinking that books will tell you all you need to know. Not necessarily. Not if, for example, you’re so enthralled in your wolf education that you walk right in the path of a wolf’s 42 sharp teeth. As you’re reading about how wolves eat many different animals including… rabbits.

Gravett includes a disclaimer– no rabbits were injured, the book is only fiction. And then “for more sensitive readers”, she gives us an alternate ending in which bunny and wolf become fast friends and share a sandwich. The end. But the final page, with a pile of the bunny’s unopened mail (including a letter from the library– Wolves is overdue) suggests that all might not be well after all in the land of bunny. But I took care not to point that out to Harriet.

September 27, 2011

Suitable Precautions by Laura Boudreau

There was a period in which Laura Boudreau and I were both enrolled in the same creative writing program at UofT, though due to me being a hermit, we never met up that often. So I must say that I know the stories of Laura Boudreau considerably better than I know Laura Boudreau herself– I remember reading “Strange Pilgrims” in The New Quarterly, the strange sad story of love with a mailman, and there was her Journey Prize-nominated story “The Dead Dad Game”, which I described as “a young person’s perspective on a broken world, and that world is realized with such humour, poignancy and quirky charm.”

There was a period in which Laura Boudreau and I were both enrolled in the same creative writing program at UofT, though due to me being a hermit, we never met up that often. So I must say that I know the stories of Laura Boudreau considerably better than I know Laura Boudreau herself– I remember reading “Strange Pilgrims” in The New Quarterly, the strange sad story of love with a mailman, and there was her Journey Prize-nominated story “The Dead Dad Game”, which I described as “a young person’s perspective on a broken world, and that world is realized with such humour, poignancy and quirky charm.”

So I thought I knew what to expect with Boudreau’s first book, the story collection Suitable Precautions, but it seems that Laura Boudreau writes to thwart expectations. Which I discovered when I read her book whose stories refused to be pinned down and be any one thing. Yes, we have “The Dead Dad Game”, which is just as good upon rereading, just your standard tale of two half-siblings lying on their father’s grave seeking out good vibrations (as the urging of the siblings’ one surviving parent), after which the creepy neighbour’s pot-bellied pig is maimed in a collision so that the siblings have to create apologetic chalk drawings.

For the first time here, I read her story “The Vosmak Geneology”, about the daughter of the daughter of alleged immigrants, whose mother becomes brain injured by a falling picnic table, loses the capacity for abstract thought or imaginings, then eventually creates a phenomenally popular series of children’s books, factually based upon the life of our narrator who spends her time doing homework in the window of a gypsy’s. “The Meteorite Hunter” about a divorced father who doesn’t quite rue his sorry past, but certainly ruminates upon it as he drives with his stranger daughter to visit a man who’s reported to be able to detect meteorites where they fall (and of course, what father and daughter find that their destination is not what they’d expected).

So what I mean by this is that Laura Boudreau’s stories are not “about” just any one thing, but rather they’re about story, about narrative, about the way a writer starts in one place and ends up in another. I mean, speaking of destinations not expected, that none of these stories will take you where you think you’re on your way to, that these are wild sprawling narratives, and yet Boudreau’s writing is so absolutely controlled. There is a tightness, a deliberateness to the way that she makes the jump from even once sentence to another a determined leap like, “I remember seeing a man in a paper gown masturbating in the hallway. We stayed for lunch.”

In terms of tightness, deliberateness, there is nothing else like Boudreau’s command of the first person voice, however. She does young people so well, in “The Dead Dad Game”, and also in “Poses”, which manages to be a story about a young girl posing for an internet pornographer but also be hilarious. I think my favourite story of the collection is “The D&D Report”, which is another of Boudreau’s stories that start somewhere and end up somewhere else, and manages to have years pass effortlessly as its narrator goes from slacker-lifeguard with a yearning for med. school to a doctor with a husband whose whole life is built on uncertain foundations.

Suitable Precautions is a curious book, the kind of book I had to talk about with somebody else as I read it, because there was so much to say. It’s the kind of collection that might appeal to another short story writer, Carolyn Black, who remarked in her interview with me, “For me, now, writing that explains everything requires a good deal of patience, if only because I’ve read so much of it; writing that resists explication seems beautiful and true.”