November 1, 2012

Kids' book review: I'm Bored

I was really pleased to review I’m Bored by Michael Ian Black and Debbie Ridpath Ohi in the October issue of Quill & Quire. It’s a funny, thoughtful book that takes the readers somewhere, and the scraggly-haired protagonist is just the kind of spunky girl I like to see in picture books. I also appreciate that it’s a book with a female protagonist that will appeal to boy readers as much as the girls.

I was really pleased to review I’m Bored by Michael Ian Black and Debbie Ridpath Ohi in the October issue of Quill & Quire. It’s a funny, thoughtful book that takes the readers somewhere, and the scraggly-haired protagonist is just the kind of spunky girl I like to see in picture books. I also appreciate that it’s a book with a female protagonist that will appeal to boy readers as much as the girls.

From my review: “Fans of Mo Willems’ Elephant and Piggie series will delight in the latest book by American comedian Michael Ian Black, illustrated by Toronto graphic artist Debbie Ridpath Ohi. Echoing Willems, Black’s story is constructed around the dialogue of an unlikely couple, in this case a small girl and a potato. The text is perfectly complemented by Ohi’s quirky minimalist drawings.”

You can read the rest here.

October 30, 2012

Hatchback

Where have I been? Nowhere, actually, except consumed by projects and daily life, plus we’re giving up napping at our house, which is cutting into my reading time. And so the past few days, I’ve been reading instead of blogging when I had the chance– the wonderful Elizabeth Stories, which I can’t wait to write about here. Had a wonderful night out with Stuart on the weekend, with dinner and Ira Glass at Massey Hall! Halloween has also become a full-time preoccupation–we’ve had three parties so far, and it’s not even Halloween yet. I’m also getting ready for the Wild Writers Festival this weekend, where at my session I will advise writers not to write blog posts in which they apologize for not blogging. So I’m kind of breaking my own rule now, but then consistency has never been my strong point, and I’m not apologizing either. Also, I can’t believe I haven’t told you about the eventful IFOA night I attended last week (I am the anonymous woman calling out angrily), with the marvellous Anakana Schofield (who came over for breakfast on Saturday) and that I met Leanne Shapton!!!, which went much smoother than the time I met Joan Didion. Thank goodness.

Where have I been? Nowhere, actually, except consumed by projects and daily life, plus we’re giving up napping at our house, which is cutting into my reading time. And so the past few days, I’ve been reading instead of blogging when I had the chance– the wonderful Elizabeth Stories, which I can’t wait to write about here. Had a wonderful night out with Stuart on the weekend, with dinner and Ira Glass at Massey Hall! Halloween has also become a full-time preoccupation–we’ve had three parties so far, and it’s not even Halloween yet. I’m also getting ready for the Wild Writers Festival this weekend, where at my session I will advise writers not to write blog posts in which they apologize for not blogging. So I’m kind of breaking my own rule now, but then consistency has never been my strong point, and I’m not apologizing either. Also, I can’t believe I haven’t told you about the eventful IFOA night I attended last week (I am the anonymous woman calling out angrily), with the marvellous Anakana Schofield (who came over for breakfast on Saturday) and that I met Leanne Shapton!!!, which went much smoother than the time I met Joan Didion. Thank goodness.

October 25, 2012

My Grade 12 English Text

I’ve started reading Isabel Huggan’s The Elizabeth Stories, because mention of it keeps turning up here and there, and because I keep spying it on terribly clever people’s bookshelves. I got a used copy last weekend, and opened it for the first time this morning to start reading “Celia Behind Me”: “There was a little girl with large smooth cheeks who lived up the street when I was in public school.” And I realized that I’d read this story before, more than once. It was so strangely familiar, like something I’d known in a dream, but somebody else’s dream. So distant because I’d read it a long time ago.

I’ve started reading Isabel Huggan’s The Elizabeth Stories, because mention of it keeps turning up here and there, and because I keep spying it on terribly clever people’s bookshelves. I got a used copy last weekend, and opened it for the first time this morning to start reading “Celia Behind Me”: “There was a little girl with large smooth cheeks who lived up the street when I was in public school.” And I realized that I’d read this story before, more than once. It was so strangely familiar, like something I’d known in a dream, but somebody else’s dream. So distant because I’d read it a long time ago.

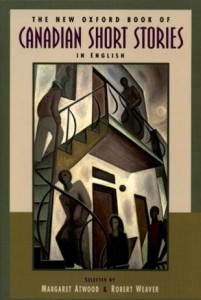

A little investigation revealed that I’d read the story in The New Oxford Book of Canadian Short Stories, edited by Margaret Atwood and Robert Weaver. I remembered the text, a row of spines lined up on the shelf in my grade 12 English classroom. I’d remembered “Celia Behind Me,” and also a story called “White Shoulders” (I remember being perplexed by it) which I was surprised to find out was by Linda Svendsen. (Alice Munro’s “The Red Dress” was not in the collection, but I remember reading that story too in the class.)

I was most surprised to discover that right there in my high school text were all these writers who I feel as though I’ve discovered in the last few years and who’ve become really important to me– Bronwen Wallace, Caroline Adderson, Cynthia Flood. And that Leon Rooke was there too, and John Metcalf, Clark Blaise, Diane Schoemperlen, Barbara Gowdy, Douglas Glover, Thomas King. I am pretty sure that we didn’t read “We So Seldom Look on Love” in my grade 12 English class, but I am just as sure that if I encountered many of these stories again, they would seem as instantly familiar as “Celia Behind Me” did.

This re-encounter has given me a new appreciate for the hoopla surrounding the Salon de Refuses and the Penguin Book of Canadian Short Stories in 2008. Well-curated anthologies are the optimum way for students to discover the short story, each one onto itself, one at a time. These seminal texts are also more important and influential than I’d before supposed, definitely sowing the seeds of love for short stories and for (Canadian) literature.

For me, it would take awhile for the love to bloom. I would not be exposed to contemporary writing this good again for years, and years, and I’d have to seek it out for myself. But maybe I hadn’t been on my own entirely. It’s been a meandering path from from there to here, but I am pretty sure that the me who picked up Isabel Huggan this morning (for fun) has The New Oxford Book of Canadian Short Stories to thank for a lot of the journey.

October 24, 2012

On the Rosalind Prize

So thrilled to read about the advent of the Rosalind Prize, Canada’s new literary prize for fiction by women. Which is not to say that Canada needs more literary prizes in general, but I think we need this one. Two years ago, I shared my thoughts on the Orange Prize, and I haven’t changed my mind. Oh, and you know my feelings on women and the Leacock Prize. Anyway, it turns out that the stats for women and Canadian literary prizes are as pathetic as all the others.

In a week during which the same old (justified) woes about women’s representation were aired again, and a venerable Canadian publisher faces peril, it is refreshing to see action for positive change and it’s really nice to be inspired.

October 22, 2012

Heidegger Stairwell by Kayt Burgess

I loved Heidegger Stairwell, a novel by Kayt Burgess, which seems to be an excellent companion to Sophie B. Watson’s Cadillac Couches, another CanLit musical ode which I recently read. Both are about musical fandom and friendship, with cross-Canada road trips thrown in for good measure. Burgess’ novel is structured as a work-in-progress, a tell-all book by music journalist Evan Strocker about his long relationship with the world-famous Canadian band Heidegger Stairwell, though he’s a little too close to his subject, as suggested by editorial notes from the band which are scattered throughout the manuscript (“No one had an STD. We are talking about something different. I told Evan that.–Coco”). Evan takes the band from their humble beginnings in a thinly veiled Elliott Lake ON–charismatic figures and musical prodigies colliding in high school hallways– to regional stardom, eventual breakup, and then reunion after their six-song EP becomes an underground sensation. It soon becomes clear (or at least Evan would like us to think so) that Heidegger Stairwell would not exist without Evan Strocker’s orchestrations, and we begin to understand that the band itself only exists to give Strocker’s universe coherence and his life some meaning.

I loved Heidegger Stairwell, a novel by Kayt Burgess, which seems to be an excellent companion to Sophie B. Watson’s Cadillac Couches, another CanLit musical ode which I recently read. Both are about musical fandom and friendship, with cross-Canada road trips thrown in for good measure. Burgess’ novel is structured as a work-in-progress, a tell-all book by music journalist Evan Strocker about his long relationship with the world-famous Canadian band Heidegger Stairwell, though he’s a little too close to his subject, as suggested by editorial notes from the band which are scattered throughout the manuscript (“No one had an STD. We are talking about something different. I told Evan that.–Coco”). Evan takes the band from their humble beginnings in a thinly veiled Elliott Lake ON–charismatic figures and musical prodigies colliding in high school hallways– to regional stardom, eventual breakup, and then reunion after their six-song EP becomes an underground sensation. It soon becomes clear (or at least Evan would like us to think so) that Heidegger Stairwell would not exist without Evan Strocker’s orchestrations, and we begin to understand that the band itself only exists to give Strocker’s universe coherence and his life some meaning.

I’ve never encountered a character like Evan Strocker in fiction before, a transgender man and an abashedly serious shit-disturber. Growing up in small-town Ontario as Evie, he fit in nowhere except with the band. He started off dating their drummer as a young teenager, and then became embroiled in torrid and/or complicated romances with most of the other band members as time went by. He’s not a protagonist who’s crying out to be liked, or perhaps it’s that he really is, but he has no idea how to go about making it happen.

Heidegger Stairwell was the 2011 winner of the 3 Day Novel contest, and while I thought that last year’s winner was a fun, cute read that was pretty good for a winner of the 3 Day Novel contest, I was pleasantly surprised to discover that this year’s is just really good full stop. Burgess comes with university degrees with classical music and creative writing, so she knows what she’s doing here. And it doesn’t really matter how long it took her to do it; she’s created a novel that’s outside of ordinary.

October 18, 2012

Our Best Book of the Library Haul: The Green Ship by Quentin Blake

We haven’t had a best book from the library haul in ages, not because the book are no good but because they generally all are, and because life is whirling along at a frenzied pace here so that library books are not what our days hinge about as they once did. But then we picked up Quentin Blake’s The Green Ship from a display at the library about sea and boat books. What a strange, mysterious, magical book about a brother and sister on holiday with an aunt who scramble over a wall to find themselves in a secret garden that is more like a jungle. And in the centre of the garden, they discover a ship except it is not a ship. It’s a strange fixture designed to look like a ship, built from pruned trees, and two tall trees which function as masts. A kind of garden shed is near the front, and inside the brother and sister discover a ship’s wheel, and then they’re discovered themselves.

We haven’t had a best book from the library haul in ages, not because the book are no good but because they generally all are, and because life is whirling along at a frenzied pace here so that library books are not what our days hinge about as they once did. But then we picked up Quentin Blake’s The Green Ship from a display at the library about sea and boat books. What a strange, mysterious, magical book about a brother and sister on holiday with an aunt who scramble over a wall to find themselves in a secret garden that is more like a jungle. And in the centre of the garden, they discover a ship except it is not a ship. It’s a strange fixture designed to look like a ship, built from pruned trees, and two tall trees which function as masts. A kind of garden shed is near the front, and inside the brother and sister discover a ship’s wheel, and then they’re discovered themselves.

They discovered by an older woman and the man she calls Bosun (“boatswain”, and actually he resembles a gardener). Stowaways, the boy and girl are made to scrub the deck, which is really to sweep away leaves, and then they all take tea and have madeira cake. The man and woman are all too happy to have the boy and girl join their crew, and so for the rest of the children’s holiday, they all partake in the ship life together.

I love this book for the same reason I love most of my favourite children’s books: because there is another story going on beneath the surface but we’re not privy to its details. In this video, Blake suggests that the old woman had lost her husband at sea, that he’s the “captain” she references, and that the green ship is a memorial to him. The story is viewed through the children’s eyes only who never stop and wonder at the circumstances around this wondrous thing they’ve found, and I actually like that the woman’s story is left untold. I like that it might not occur to children to wonder why grown-ups do any of the inexplicable things they do.

I loved the story’s climax, when the green ship is taken by a storm and it is though the ship is really a ship at sea as the rain pounds and the wind blows, and the old woman steers the ship and remembers what the Captain would have advised her: “Steer into the eye of the storm”. I have no idea if that’s really good advice, but it’s a line I love, and I imagine that it’s applicable somewhere.

October 16, 2012

(Some) Mothers are Writers

On Harriet’s long-form birth certificate, it is written that her mother is a writer. And while I don’t remember much of those blurry days after she was born, when our world was exploded pieces held together with love and hanging on just barely, I remember filling out that form, hunched over my laptop on our coffee table. When we’d got to Mother’s Occupation, we’d paused for a moment. I was three weeks into maternity leave from a job I wouldn’t go back to, from the least meaningful job title in the universe, which was “research administrator.” We couldn’t write that, and besides, I was no longer one. “Why not say, ‘writer’?” my husband suggested, and so we did.

On Harriet’s long-form birth certificate, it is written that her mother is a writer. And while I don’t remember much of those blurry days after she was born, when our world was exploded pieces held together with love and hanging on just barely, I remember filling out that form, hunched over my laptop on our coffee table. When we’d got to Mother’s Occupation, we’d paused for a moment. I was three weeks into maternity leave from a job I wouldn’t go back to, from the least meaningful job title in the universe, which was “research administrator.” We couldn’t write that, and besides, I was no longer one. “Why not say, ‘writer’?” my husband suggested, and so we did.

It is often noted as monumental, that moment when a writer learns to call herself as such, when she gathers the confidence, courage and faith necessary to embark upon a creative path. Which I don’t have a whole lot of truck with. I think we sentimentalize these things too much, that we spend too much time with our heads up our asses, and that a woman staring into the mirror practicing calling herself a writer is like Annie Dillard’s writer who “himself only likes the role, the thought of himself in a hat.” I would argue that more important that learning to call oneself a writer is to write and (even better) to write well and to get the work out there so that everyone will know you’re a writer, and what you think doesn’t really matter.*

So this isn’t about how I lied on official documentation and was professionally transformed, never to administrate research ever again. This isn’t about how I learned to call myself a writer, but instead about how everybody’s wrong about motherhood (and by “everybody”, I mean mainly The Atlantic and Newsweek).

Something funny started happening as soon as I got pregnant in 2008. Professionally speaking, research administration aside, it hadn’t been a great time for me. I was a year out of a graduate creative writing program that had failed to take me places, my classmates were publishing books and I was getting rejection after rejection from lit mags. That post-school thing is always brutal, and from creative writing programs in particular. I remember Anne Patchett writing in her memoir of her friendship with Lucy Grealy how they finished the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and had to “write to save their lives” (I paraphrase). It wasn’t working for me. And so when I got pregnant, it seemed like the writing thing was going to be put aside for awhile. At least I would have another focus.

Life, it seemed, would have other plans. Coinciding with my first trimester were some interesting writing opportunities, an invitation to speak on a panel about literary blogging with the Governor General, increased attention to my blog, and some wonderful new writerly connections. By the time Harriet was born, I’d started writing book reviews, had a couple of stories published, and cheques were arriving pretty regularly, even if they were pitifully small. So when I wrote, “Writer” on her birth certificate, I wasn’t entirely delusional. But it wasn’t entirely true yet either.

I suppose it’s still not wholly true, if we’re speaking in terms of finances, because if I didn’t have a husband who worked full time, we’d be in trouble around here. But I’ll tell you this much, because I’m proud of it, and not because it’s the most important thing, because it isn’t: every month, I make our rent. It’s something. Since I became a mother 3.5 years ago, I’ve managed to put together a hard-scrabbled, deeply fulfilling professional life involving writing, editing, teaching and reviewing. And while motherhood has not been integral to this, as though it unleashed some deep creative fount within me, neither has it been an impediment. In fact, it’s helped hugely with the process in practical terms. It gave me a reason to leave my boring 9-5 job. It’s been the inspiration for some of the best stuff I’ve ever written. I’ve made mother-friends who are inspiring writer-friends in their own right. And motherhood has given me the ability to focus, to sit down and get the words out. Harriet has been in playschool since September and I’ve had mornings for working, and I promise you that I’ve not wasted away a single one.

Now obviously, motherhood is not necessary for career success, for many it really does stand in the way, and plenty of writers have really done quite well without kids. Plenty of mothers are also happy enough to be focusing on motherhood alone. Many jobs don’t mix with motherhood quite so tidily. Quite obviously too, our rent is fairly cheap and I could stand to be way more successful. And furthermore, fortune has been good to me. I am enormously privileged. But–

I am thinking about all this now in connection with Jessa Crispin’s column “The Pram in the Hall“, about how fraught is the question of whether or not to have children for creative professionals in particular. She writes, “The reason why it’s so difficult to think through your decision is because people keep pretending like there is one way this motherhood thing could go, when in reality there are millions.” Which she sees as terrifying as it is rife with potential, but from where I stand now it’s mostly the latter. Like everything with parenthood, when people complain about kids being expensive, demands on parents’ time, how you have to give your kids your all, how you just have to have an exer-saucer just you wait, I throw up my arms and shriek, “It doesn’t have to be this way!” There is not only one way this motherhood thing can go. Because life happens. Also, free will doesn’t get taken out along with the placenta.

For mothers, as with women, and as with people (and I’ve made the connection between mothers and people before), there are reassuringly myriad ways to be. We have to broaden and complicate our understanding of what motherhood is and who mothers are if we ever want the conversation about motherhood to be one from which we actually learn something.

*Obviously, I was a child in the 1980s when our education system was robust, my teachers told me I could anything, and my parents underlined this point over and over. So I can afford to be so flippant.

October 14, 2012

The Cutting Season by Attica Locke

Attica Locke’s 2010 novel Black Water Rising was the most unlikely finalist for The Orange Prize. Not because it wasn’t good, but because cinematic crime fiction is hardly Orange-y fare. It was one of my favourite books of the year, however, so steeped in place and time with a plot that wouldn’t let go. It concluded with a suggestion that the book wasn’t quite over yet, that Locke would be taking Houston lawyer Jay Porter into another story, and so it comes as a bit of a surprise to me that in her second novel, she’s shifted gears so much.

Attica Locke’s 2010 novel Black Water Rising was the most unlikely finalist for The Orange Prize. Not because it wasn’t good, but because cinematic crime fiction is hardly Orange-y fare. It was one of my favourite books of the year, however, so steeped in place and time with a plot that wouldn’t let go. It concluded with a suggestion that the book wasn’t quite over yet, that Locke would be taking Houston lawyer Jay Porter into another story, and so it comes as a bit of a surprise to me that in her second novel, she’s shifted gears so much.

A surprise, but not a disappointment. Although Locke starts from scratch in The Cutting Season, the writing is just as tight, the story just as solid. The setting now is rural Louisiana, a sugar plantation turned tourist attraction called Belle Vie. Everything, from the big house to the slave cottages, is preserved exactly as was, which means something different to everyone who comes to see it, whether it be Scarlett O’Hara glamour or the travesty of slavery. For Caren Gray, Belle Vie is home, where her ancestors worked until they were freed, and where they continued to work even after. Her own mother had been the plantation’s cook, and it’s where Caren herself has come back to work as manager after a failed relationship and losing her New Orleans home to Hurricane Katrina. Belle Vie is a return to her roots, but also a fresh start as she aims to give her young daughter the best opportunities in life.

The idyll is broken when a dead body is discovered on the plantation grounds, the body of a migrant worker who’d toiled in nearby farming fields in a way not so different from Caren’s own ancestors a century before. The Cutting Season draws its own parallels between slavery and America’s illegal migrant agricultural workforce, and also becomes about real estate, slavery’s legacy, the modern South and its relationship to its complicated past. Though she never finished law school, Caren has background enough to know that a young Black man who works for her is being set up for a crime that he didn’t commit, and that a cover-up is going on. Her first priority, however, is to protect her daughter who appears to know more about the murder than what she lets on. To that end, her ex arrives to suss out the situation, and to provide his own expertise–he’s a lawyer proper now working in DC at Obama’s White House. He’s just weeks away from his wedding but the past between he and Caren, as the past always does in the American South, just refuses to rest.

There were a few clunky moments, the kind that cause you to shout, “Don’t go down in the basement!” at the horror movie heroine, but these were overridden by the book’s general goodness, its complexity, depth and the brilliance of Attica Locke’s prose. The Cutting Season was the first novel selected for a new imprint by crime writer Dennis Lehane, and it’s easy to see why. It’s a gripping, unforgettable book about the connections between history and now.

October 14, 2012

On Barbara Gowdy, cut-out cookies, and other decapitations

Over the weekend, I read Barbara Gowdy’s We So Seldom Look on Love, which readers and writers I admire have been talking about for years. In a collection full of devastating stories, I was most devastated by “Lizards”, in which a woman’s very tall lover decapitates her baby daughter by carrying her on his shoulders and walking too close to a ceiling fan. For some reason, I thought this was an essential plot point to share with my family, including those among us who are 3.

Over the weekend, I read Barbara Gowdy’s We So Seldom Look on Love, which readers and writers I admire have been talking about for years. In a collection full of devastating stories, I was most devastated by “Lizards”, in which a woman’s very tall lover decapitates her baby daughter by carrying her on his shoulders and walking too close to a ceiling fan. For some reason, I thought this was an essential plot point to share with my family, including those among us who are 3.

Harriet, whom I’ve accidentally given a fascination for all things macabre, couldn’t get enough of this story. “What happened next?” she asked. “Well,” I said. “The baby died. Her head fell off.” And no, it couldn’t have been put back on. Harriet eventually suggested that they should probably get a cutting board and cut off its arms and legs for good measure. And then we decided it would be an excellent idea to bake some gingerbread men.

Well, not gingerbread, exactly. We made “chewy oatmeal” cut-out cookies, but we call them gingerbread men anyway. Even the women. Their chewiness was part of their appeal, but it also meant that the men were partial to losing limbs and that the day’s focus on decapitation continued. Stuart and I surreptitiously gobbled up the casualties, which meant that by the time the cookies were all decorated and Harriet was permitted to have her “just one”, we were about ready to be sick.

Incidentally, this version of The Gingerbread Man story is our favourite. As with Gowdy, its author doesn’t shy away from darkness, but points out that a cookie getting eaten is far from the worst way a story could end.