November 15, 2012

Virginia Lee Burton: A Sense of Place

One day when I finally get my act together, I will write an enormous blog post about how this summer we ended up buying every single book Virginia Lee Burton ever wrote. The entire Virginia Lee Burton library, which now lives on a shelf in the living room, rather than in Harriet’s room with the other kids’ books. Harriet adores them all, and they mean a whole lot to all of us, actually. I read Burton’s biography last year, and it only increased my appreciation for her work, for her genius. To learn how important she considered book design to be, how innovative she was as an illustrator, the extraordinary praise her sons had for her as an artist and as a mother, the richness of her life, and her vision. I learned that beyond her books, Burton was also a well-known textile designer, founder of the Folly Cove Designers artistic community. She was brilliant, and her work is timeless, and her ideas have influenced the way I’ve come to understand the world, and my relationship to my child.

So in all my enthusiasm, I was pleased to discover a 2008 PBS documentary about Burton called Virginia Lee Burton: A Sense of Place. Stuart and I borrowed it from the library and sat down to watch it last weekend, and while much of the material was familiar to me from the biography (whose author acted as a consultant for the film), I enjoyed the movie very much. Interviews with Burton’s sons, friends and fellow-artists, and even Dickie Birkenbush himself! Other interviews with children’s authors, librarians, academics and artists provided great context to Burton’s story and underlined her singularity.

I don’t know that I’d ever paid attention to Burton’s books’ feminist angle. She wrote with her sons as her intended audience so that her subject matter is decidedly “boyish” (not that it stops my girl!)–a train, a steam shovel, a snow plow, a cable car, a horse in a Western. But all her subjects–the train, the steam shovel, the snow plow, the cable car, the house and even the Little House herself–are charactertized as female. The female characters are equal partners with male characters, independent, strong and hard-working. Which provides me with a whole new level of appreciation for these books, though it’s not as though I needed one…

See also: “What Sally Draper must have been reading: Virginia Lee Burton and Mad Men”

More details about the doc are here.

November 13, 2012

Where Are the Parents? 8 Excellent Books about Inattentive Moms and Dads

(Exciting note! This is my first cross-post to the excellent Bunch Family site. Hope you enjoy, and check out the scene there as well.)

They are useful, books about inattentive moms and dads. They prepare children for independence and allude to parents having their own complexities and places in the world beyond the family. A parent-free universe also paves the way for marvelous fictional adventures.

Sunday Morning was created by kid-lit royalty, Judith Viorst of Alexander and the No Good Very Bad Day and Hilary Knight, who drew Eloise. Fantastic silhouette drawings show Mom and Dad stumbling home after midnight, re-tucking the kids into bed and making them promise not to make a peep until 9:45 am (“and we’ll tell you when that is”). The rest of the story is about the kids creating havoc in attempts to entertain themselves, (“We colour. We paste. We build a tower higher than my bed”) with a parent calling out from the bedroom, “Some boys are going to be spanked” every few pages. It’s a story of sibling tension, imagination, fun, and the happy ending of well rested parents.

Sunday Morning was created by kid-lit royalty, Judith Viorst of Alexander and the No Good Very Bad Day and Hilary Knight, who drew Eloise. Fantastic silhouette drawings show Mom and Dad stumbling home after midnight, re-tucking the kids into bed and making them promise not to make a peep until 9:45 am (“and we’ll tell you when that is”). The rest of the story is about the kids creating havoc in attempts to entertain themselves, (“We colour. We paste. We build a tower higher than my bed”) with a parent calling out from the bedroom, “Some boys are going to be spanked” every few pages. It’s a story of sibling tension, imagination, fun, and the happy ending of well rested parents.

In Alfie’s Feet, by the wondrous Shirley Hughes, the parents are attentive enough, usually frazzled actually and totally on top of the shoe shopping, but I always like that in Shirley Hughes’ books, Mum and Dad are seen relaxing with obligatory cups of tea. Further, when Dad takes Alfie to the park to try out his new rain-boots, Dad takes not only his book along with him but also his newspaper. Alfie is shown splashing happily in the puddles while Dad reads on the periphery, comfortably parked on a bench.

In Alfie’s Feet, by the wondrous Shirley Hughes, the parents are attentive enough, usually frazzled actually and totally on top of the shoe shopping, but I always like that in Shirley Hughes’ books, Mum and Dad are seen relaxing with obligatory cups of tea. Further, when Dad takes Alfie to the park to try out his new rain-boots, Dad takes not only his book along with him but also his newspaper. Alfie is shown splashing happily in the puddles while Dad reads on the periphery, comfortably parked on a bench.

Things take a more sinister turn in “Disobedience” by A.A. Milne, a poem from his collection When We Were Very Young. Most of the fun of this one lies in the rhythm, and reading aloud:

Things take a more sinister turn in “Disobedience” by A.A. Milne, a poem from his collection When We Were Very Young. Most of the fun of this one lies in the rhythm, and reading aloud:

James James

Morrison Morrison

Weatherby George Dupree

Took great

Care of his Mother,

Though he was only three.

James James Said to his Mother,

“Mother,” he said, said he;

“You must never go down

to the end of the town,

if you don’t go down with me.

Naturally, Mother disobeys and goes to the end of the town anyway, never to return. The poem is useful for the attention it pays to children’s fears of separation from their parents, and also for its mysteries, its strangeness, the questions it leaves unanswered.

A exuberant, boisterous book, There Were Monkeys in My Kitchen is certainly one that leaves the reader asking, “Where are the parents?” Written by Canadian poet Sheree Fitch and recently re-issued with new illustrations by Sydney Smith, Monkeys is the story a small girl who is left defenceless as her house is overtaken by simian creatures. “I said, ‘This place is CHAOS!’ I said, ‘BABOON catastrophe!’ You folks have got to help! You’ve got to rescue me!” But nobody comes, even though she’s called the police and RCMP. And by the time help arrives, it’s already too late.

A exuberant, boisterous book, There Were Monkeys in My Kitchen is certainly one that leaves the reader asking, “Where are the parents?” Written by Canadian poet Sheree Fitch and recently re-issued with new illustrations by Sydney Smith, Monkeys is the story a small girl who is left defenceless as her house is overtaken by simian creatures. “I said, ‘This place is CHAOS!’ I said, ‘BABOON catastrophe!’ You folks have got to help! You’ve got to rescue me!” But nobody comes, even though she’s called the police and RCMP. And by the time help arrives, it’s already too late.

Absent parents are a trusting, benevolent force in Caroline Woodward and Julie Morstad’s Singing Away the Dark, which was nominated for all the major Canadian children’s book prizes in 2011. It’s about a six-year-old girl in a rural community who must walk through the darkened woods on winter mornings to get to her school bus stop. In verse, Woodward describes how the girl summons all her courage by trudging forth and singing loud: “I see a line of big old trees, marching up the hill. ‘I salute you, Silent Soldiers! Help me if you will.’” The verse is perfectly complemented by the detail of Morstad’s delightful drawings.

Absent parents are a trusting, benevolent force in Caroline Woodward and Julie Morstad’s Singing Away the Dark, which was nominated for all the major Canadian children’s book prizes in 2011. It’s about a six-year-old girl in a rural community who must walk through the darkened woods on winter mornings to get to her school bus stop. In verse, Woodward describes how the girl summons all her courage by trudging forth and singing loud: “I see a line of big old trees, marching up the hill. ‘I salute you, Silent Soldiers! Help me if you will.’” The verse is perfectly complemented by the detail of Morstad’s delightful drawings.

Similarly a story of bravey, Maurice Sendak’s Outside Over There is a long way from the wild rumpus of Where the Wild Things Are. “When Papa was away at sea,” it begins, “and Mama in the arbor, Ida played her wonder horn to rock the baby still—but never watched.” Mama is clearly suffering from some kind of depression, and Ida has been left in charge of her baby sister, who is stolen away by goblins when Ida turns her back. It’s a strange, disturbing tale, with simple prose given enormous depth by Sendak’s remarkable illustrations, but small children have an appreciation for questions without answers and they might better understand this book than their parents do. Heroic Ida triumphs in the end, rescuing the baby and bringing her home.

Similarly a story of bravey, Maurice Sendak’s Outside Over There is a long way from the wild rumpus of Where the Wild Things Are. “When Papa was away at sea,” it begins, “and Mama in the arbor, Ida played her wonder horn to rock the baby still—but never watched.” Mama is clearly suffering from some kind of depression, and Ida has been left in charge of her baby sister, who is stolen away by goblins when Ida turns her back. It’s a strange, disturbing tale, with simple prose given enormous depth by Sendak’s remarkable illustrations, but small children have an appreciation for questions without answers and they might better understand this book than their parents do. Heroic Ida triumphs in the end, rescuing the baby and bringing her home.

The tone is lighter in Mairi Hedderwick’s Katie Morag Delivers the Mail. Katie Morag lives on a tiny island in the Scottish Hebrides, where her mother is the postmistress and her father manages the general store. One day when her parents are particularly busy, Katie Morag is put in charge of delivering the mail. Things go awry when she gets distracted from her task, and the situation is only put right again with the help of Katie Morag’s wily granny. It’s a story about the overwhelming nature of independence, but also the surprising and liberating fact of how much one can get away with in actuality.

The tone is lighter in Mairi Hedderwick’s Katie Morag Delivers the Mail. Katie Morag lives on a tiny island in the Scottish Hebrides, where her mother is the postmistress and her father manages the general store. One day when her parents are particularly busy, Katie Morag is put in charge of delivering the mail. Things go awry when she gets distracted from her task, and the situation is only put right again with the help of Katie Morag’s wily granny. It’s a story about the overwhelming nature of independence, but also the surprising and liberating fact of how much one can get away with in actuality.

And finally, in Dennis Lee’s Jelly Belly, a collection of poems well-populated with free-range kids and inattentive parents, the mother from “Mrs. Murphy and Mrs. Murphy’s Kids” must be singled out. A modern-day version of the old woman in the shoe, Mrs. Murphy kept her kids in a can of peas but, “The kids got bigger/And the can filled up,/ So she moved them into/ A measuring cup.” The kids move from one vessel into another as they grow, eventually ending up on a mountain top. “But the kids just grew/ And the mountain broke apart,/ And she said, “Darned kids/ They were pesky from the start!” She’s eventually relieved of her duties when the kids grow up and have babies of their own. And we’re told that Mrs. Murphy’s kids kept all their kids in a can of peas, the whole unfortunate cycle beginning again.

And finally, in Dennis Lee’s Jelly Belly, a collection of poems well-populated with free-range kids and inattentive parents, the mother from “Mrs. Murphy and Mrs. Murphy’s Kids” must be singled out. A modern-day version of the old woman in the shoe, Mrs. Murphy kept her kids in a can of peas but, “The kids got bigger/And the can filled up,/ So she moved them into/ A measuring cup.” The kids move from one vessel into another as they grow, eventually ending up on a mountain top. “But the kids just grew/ And the mountain broke apart,/ And she said, “Darned kids/ They were pesky from the start!” She’s eventually relieved of her duties when the kids grow up and have babies of their own. And we’re told that Mrs. Murphy’s kids kept all their kids in a can of peas, the whole unfortunate cycle beginning again.

November 12, 2012

Sleeping Funny by Miranda Hill

It’s so tough to review a short story collection with any authority. Whenever I go declaring the “strongest story in the collection,” the book reviewer next door will go and call it the weakest, or not even mention the story at all in his review. And that one story that just didn’t do it for me will be the one that someone else celebrates.

It’s so tough to review a short story collection with any authority. Whenever I go declaring the “strongest story in the collection,” the book reviewer next door will go and call it the weakest, or not even mention the story at all in his review. And that one story that just didn’t do it for me will be the one that someone else celebrates.

In truth, it’s tough to review any book with real authority, but most short story collections definitely further complicate the task. So much really is just a matter of taste, so that of course I’d be the least enamoured with Miranda Hill’s “Rise: A Requiem” because historical fiction just doesn’t do it for me, while “The Variance” absolutely held me enraptured, but then I’ve got a thing for stories about middle-class wives and mothers and leafy streets, don’t I?

When I review short stories, I like to talk about the book as a whole rather than necessarily break it down into parts, but Sleeping Funny makes this nearly impossible. I could say, I guess, that this is not a seamless, well-curated, devourable collection. This is not a book that seems to be more than the sum of its parts, and yet… its parts are extraordinary at times and altogether worthwhile.

What I will say is that I am so very glad this book exists. Because it’s really a beautiful object, comprising stories by a writer who won our nation’s top story prize in 2011, because the stories themselves are rich and deep, and because not every publisher these days is going to take a chance on a collection whose stories are so disparate. Because this is a book less about its bookishness than about the stories themselves. A celebration of stories, nine of them, which demonstrate the remarkable range of what a short story can be.

“The Variance” really was my favourite, the latest addition the Canon of Can-Lit Lice. Written from a dizzily shifting array of perspectives, it’s the story of neighbours on a well-to-do street and how their lives are disrupted when a new family moves in and casts the reality of their lives in an unflattering light (and plus, they’re petitioning to cut down the old maple). A bit Meg Wolitzer, a bit Tom Perrotta, this story also shows the influence of Zsuzsi Gartner, under whom Hill has studied. I also enjoyed “Sleeping Funny”, the story that ends the collection. It’s about a woman who has failed to live up to her early potential and now must come home to pack away the pieces of her (hoarder) father’s life after his death, and is struggling to keep a pet fish alive in order for her young daughter to have something to believe in.

I’ve got a thing for realism too, which is probably why these two stories worked best for me. The others read more as experiments, though they’re grounded by the same detail that made “The Variance” and “Sleeping Funny” so successful. In “Apple”, a high school sex-ed class is traumatized by visions of the circumstances of each of their own conceptions (except for Amanda Axley, “a brainiac in a family of rednecks” who is thrilled to learn she was the product of an illicit affair with a handsome doctor, conceived in the back of a supply closet). “Petitions to St. Chronic” is winner of the 2011 Journey Prize, the story of an abused wife who finds salvation in infatuation with a comatose man who has just attempted a very public suicide. In “6:19”, a man’s attempts to alter the rigid structure of his life takes him on a journey more strange than he’d ever anticipated.

“Because of Geraldine” is the story of a marriage in a shadow, the narrator looking back on her family’s infatuation with her father’s first love, who become a country and western singer. In “Precious”, a family and their whole community become enthralled by a beautiful, golden-haired infant whose older brother’s own singularity goes unnoticed. And then two stories about digging and death– “Digging for Thomas” about a young widow in WW2 whose attempts at a Victory Garden confuse her young son, and “Rise: A Requiem”, about an Anglican Minister in Kingston in the 1800s who discovers that the bodies he buries are being disturbed.

While the range is sometimes disorienting, I preferred Sleeping Funny to the kind of short story collection that perfects one trick, and then just performs it over and over. Miranda Hill’s is certainly a remarkable debut, and a promise of exciting books ahead.

November 11, 2012

We go to the theatre: Soulpepper's Alligator Pie!

Yesterday was a monumental day, as we took Harriet to see her very first play. It was Alligator Pie, an original Soulpepper production based on the works of Dennis Lee. We’d been seriously preparing for the experience by reading the book entire, which is beloved by our whole family. It’s just as wonderful as Dennis Lee knew it would be to “discover the imagination playing on things [we] live with every day”, but I suppose it’s not just about the here and now because I really love that with Dennis Lee books, Harriet is enjoying the books that were mine as a child. But yes, I love that we get to read about the streets where we live: “Yonge Street, Bloor Street,/ Queen Street, King: Catch an itchy monkey/With a piece of string.” Walking around the city, we get to see our books brought to life, and that’s an extraordinary experience, the very best way to love literature.

Yesterday was a monumental day, as we took Harriet to see her very first play. It was Alligator Pie, an original Soulpepper production based on the works of Dennis Lee. We’d been seriously preparing for the experience by reading the book entire, which is beloved by our whole family. It’s just as wonderful as Dennis Lee knew it would be to “discover the imagination playing on things [we] live with every day”, but I suppose it’s not just about the here and now because I really love that with Dennis Lee books, Harriet is enjoying the books that were mine as a child. But yes, I love that we get to read about the streets where we live: “Yonge Street, Bloor Street,/ Queen Street, King: Catch an itchy monkey/With a piece of string.” Walking around the city, we get to see our books brought to life, and that’s an extraordinary experience, the very best way to love literature.

Seeing Alligator Pie on stage took it to a whole new level though. In spite of our prep, much of the show was new to us, based on Dennis Lee poems not just from the books we know (which are Alligator Pie, Garbage Delight and Jelly Belly). And even those pieces we recognized had become otherworldly by being translated into song– “Psychapoo” as a doo-wop ballad, “Tricking” as a rap. The show was loud, and fun–I noted beaming faces in the audience all the around the theatre throughout that were mirroring my own. Its emphasis was on friendship and also on play, not one of the many props on stage ever used for a single purpose of the one you’d imagine it was intended for. The actors (who were also the show’s creators) were full of energy, charisma and talent, and did justice to their material, even made it something new.

Seeing Alligator Pie on stage took it to a whole new level though. In spite of our prep, much of the show was new to us, based on Dennis Lee poems not just from the books we know (which are Alligator Pie, Garbage Delight and Jelly Belly). And even those pieces we recognized had become otherworldly by being translated into song– “Psychapoo” as a doo-wop ballad, “Tricking” as a rap. The show was loud, and fun–I noted beaming faces in the audience all the around the theatre throughout that were mirroring my own. Its emphasis was on friendship and also on play, not one of the many props on stage ever used for a single purpose of the one you’d imagine it was intended for. The actors (who were also the show’s creators) were full of energy, charisma and talent, and did justice to their material, even made it something new.

The show was an hour long, which was the perfect length of time for any audience members who were 3. It was only in the last few minutes when Harriet announced (in a rare moment of silence in the room, of course): “I don’t want to watch this show anymore.” Which was fine, because by then it was over. We got to walk out to the theatre by stomping on a huge sheet of bubble wrap, and all of us were very satisfied with Harriet’s first theatre experience.

We’d even do it again!

November 7, 2012

Desperately Seeking Susans

When I heard about Desperately Seeking Susans, an anthology of Canadian poets called Susan, I was instantly delighted and knew this would be a book I’d have to get, and not least of all because it would probably include a poem by Susan Holbrook. So you can imagine my excitement when it all came together and I learned keeping Holbrook company would be Susans Briscoe, (Suzette) Mayr, Telfer, Olding, and Sorensen (oh yes, she of the A Large Harmonium fame!). The anthology (so reads its jacket copy) “brings together Canada’s most eminent Susans… paired with Canada’s emerging Susans”. It’s also edited by Sarah Yi-Mei Tsiang, who wrote the wonderful Sweet Devilry (which won the Gerald Lampert Prize in 2012) and is author of a few of our favourite picture books.

Now I have very good intentions when it comes to poetry; unlike many people, I even buy the stuff. But I find sitting down to read it altogether challenging sometimes, because I’m a book devourer, and poetry doesn’t always lend itself to being digested in such a manner. And so it says something about Desperately Seeking Susans that I read it over the weekend, and that reading was such a pleasure. Not that many of these poems could be read in one go– I had to read most of them twice or three times but the nice thing about the anthology was the range of poems, that each one would require a different kind of mental muscle, and so I never got exhausted. Every time I turned the page, I would discover something different and new.

Discovery is the key here. Not being the most avid poetry reader, here is where I’ve discovered some of those “eminent” poetic Susans for the very first time– Goyette, Elmslie, Ioannou. I loved the range of subject matter, from “The Coroner at the Taverna” by Susan Musgrave and “9 Liner” by Suzanne M. Steele about the war in Afghanistan, to poems about children, about elderly mothers and fathers. I love that the book’s epigraph is a poem called “Susan” by Lorna Crozier, and that the book has been blurbed by Susan Swan. I loved the first poem, “First Apology to My Daughter” by Susan Elmslie, which ends with the tremendous last line, “I taught you the ferocity of hunger,” Sue Goyette’s heartbreaking, beautiful poems about grief, Susan Holbrook’s “Good Egg Bad Seed”, which I had to read in its entirety to my husband before we went to bed on Saturday night (“You subscribe to Gourmet magazine or you don’t want fruit in your soup./ You get Gloria Steinem and Gertrude Stein mixed up or you get the Bangles and the Go-Go’s mixed up.”).

I loved Susan Glickman’s “On Finding a Copy of [Karen Solie’s] Pigeon in the Hospital Bookstore”, imagine a poem like Suzannah Showler’s with the fantastic title, “A Short and Useful Guide to Living in the World”. I was always going to love Susan Olding’s poems, which are “What We Thought About the Chinese Mothers” and “What the Chinese Mothers Seemed to Think of Us”. I could go on and on; there is everything here.

I love this is a book founded on such a fun premise, and how the richness and quality of the work did not have to suffer for that fun. It is an essential addition to the library of any Susan, or to anybody who loves poetry, or anyone who doesn’t know yet how much she really does.

November 6, 2012

Sharon Butala and Prairie Fire

My essay “True Crime” is featured in the current issue of Prairie Fire, as part of its celebration of Sharon Butala. I’m quite excited about this publication, as it’s about a book that meant a lot to me, and also because the project has been a long time coming. The opportunity to contribute to the issue came about 4 years ago when I was pregnant, and I remember accepting it with fear as I had no idea what my writing life would be like once my baby was born. “At the very least,” I remember thinking, “I will have one thing published in the next few years.” Which is funny to consider now, because I’ve been lucky enough to do so much with these few years.

My essay “True Crime” is featured in the current issue of Prairie Fire, as part of its celebration of Sharon Butala. I’m quite excited about this publication, as it’s about a book that meant a lot to me, and also because the project has been a long time coming. The opportunity to contribute to the issue came about 4 years ago when I was pregnant, and I remember accepting it with fear as I had no idea what my writing life would be like once my baby was born. “At the very least,” I remember thinking, “I will have one thing published in the next few years.” Which is funny to consider now, because I’ve been lucky enough to do so much with these few years.

I’m excited about this issue as well because it’s really beautiful, highlights a fantastic Canadian writer, and includes work by other great Canadian writers, academics and publishing folks. I’m really proud to be a part of it. Should be on newstands any day now.

November 4, 2012

The Vicious Circle reads The Wives of Bath

It occured to us to read The Wives of Bath after we read Skippy Dies last winter, whose female characters were scarcely invested with heartbeats let alone souls. We wanted some women with more than two dimensions, and in The Wives of Bath, we got what we were looking for. We liked this book, everyone. This is remarkable. Some of us had read it years ago, others encountering for the first time. A few of us kept talking about the movie Heavenly Creatures in connection. We talked about boarding school books, and how delicious they are, especially when the reader is young, even though the schools themselves are always terrible. Why the attraction then? It’s another world, it’s Lord of the Flies. We talked about Skim by Mariko Tamaki and Jillian Tamaki, and Jo Walton’s Among Others. And then we broke out the Cheetos.

It occured to us to read The Wives of Bath after we read Skippy Dies last winter, whose female characters were scarcely invested with heartbeats let alone souls. We wanted some women with more than two dimensions, and in The Wives of Bath, we got what we were looking for. We liked this book, everyone. This is remarkable. Some of us had read it years ago, others encountering for the first time. A few of us kept talking about the movie Heavenly Creatures in connection. We talked about boarding school books, and how delicious they are, especially when the reader is young, even though the schools themselves are always terrible. Why the attraction then? It’s another world, it’s Lord of the Flies. We talked about Skim by Mariko Tamaki and Jillian Tamaki, and Jo Walton’s Among Others. And then we broke out the Cheetos.

Mouse is the portal to the book, our connection to the story, which means we’re distanced from the story and predisposed for sympathy for her. We wondered if Mouse’s sad sad story was a weakness, if we’d been too driven to sympathize. How sad can one story get? And yet it was her personality rather than her tragedy than won her to us. She does guide the story, but then we related this to Great Expectations, to Pip, laying everything out for the reader. Certainly there is literary value in this approach.

We talked about connections between fact and fiction, about a real life murder than inspired the novel’s climax and about autobiographical elements of the story. We talked about how this was not a perfect novel, if there seemed to be more at work behind the book than the story itself. How the novel contained so many elements– gothic, intrigue, humour, violence, ideas– and that it lacked a certain seamlessness. It’s a book that’s doing so many different things at once. And then we pause: “But it’s so good!” It’s that we can sit down and talk about it so intensely, coming to new questions instead of conclusions. That such a readable book can have so much depth.

We talked more about boarding school, about ideas of gender which were less in the public discourse when the book came out. We wondered if different elements of the book would be focussed on now? We talked about bodies in the book, how they were all misshapen somehow, exaggerated, too big or too small. The sadness of the Father/Daughter relationship, and how she never gives up on her father. How we forget that Mouse is younger than she seems, and (as with most teenagers) she is probably not as hideous as she imagines herself to be. We are happy she no longer talks to Alice in the end. We think she is going to be okay. We talked about the film version of the book and how different it was, with its emphasis on the lesbian storyline, which doesn’t exist here, or does so less titillatingly because the lesbians in the book are two old women rather than two beautiful young girls.

We talked about what happened to Paulie, what made her the way she was? Was she transgender? Was it the trauma of her childhood? Or was her adoption of maleness simply a logical reaction to the way she would be treated as a woman in her society, as a refusal to cede her power. How ironic than a person with such disdain for femaleness would end up the ward of a lesbian in a girls’ boarding school. And then we thought about how interesting it was that everyone (and us) wants to know what is wrong with Paulie, and no one ever says, “And what about every single thing that’s wrong with the world around her?”

November 4, 2012

Wild Writers in Waterloo

I took all the wrong pictures in Waterloo yesterday at the Wild Writers Festival. The pictures that I should have taken included one of a room full of about 30 students (with such friendly faces!) who’d turned out to listen to me talk about blogging for an hour and a bit; the Wild Women Writers panel with Miranda Hill, Alison Pick, Carrie Snyder and Kerry-Lee Powell, which was such a joy and inspiration to listen to; Miranda Hill’s book Sleeping Funny, which I had to buy because its author enchanted me; photos of all the people I know from online only and was so thrilled to meet in person finally; and pictures of The New Quarterly staff and their terrific volunteers who worked so hard to make things run smoothly and make the day so enjoyable for us.

I took all the wrong pictures in Waterloo yesterday at the Wild Writers Festival. The pictures that I should have taken included one of a room full of about 30 students (with such friendly faces!) who’d turned out to listen to me talk about blogging for an hour and a bit; the Wild Women Writers panel with Miranda Hill, Alison Pick, Carrie Snyder and Kerry-Lee Powell, which was such a joy and inspiration to listen to; Miranda Hill’s book Sleeping Funny, which I had to buy because its author enchanted me; photos of all the people I know from online only and was so thrilled to meet in person finally; and pictures of The New Quarterly staff and their terrific volunteers who worked so hard to make things run smoothly and make the day so enjoyable for us.

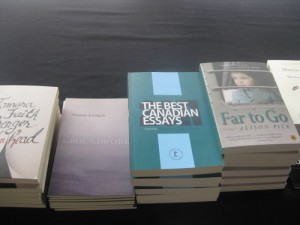

The pictures I did take were of my gourmet lunch box, which I’d been ridiculously looking forward to and which surpassed all my expectations and then some. The box was massive, and the food was so so good. I also took a picture of (part of) the booksale table (by Words Worth Books), because they’d brought in Best Canadian Essays 2011 (with my essay in it!) and put it on display beside all the other festival presenters’. I am sure it sold like hotcakes, but yes, it was kind of the honour of my life to be a little old blogger up there beside some of Can-Lit’s finest. A thrill I will never, never forget.

The pictures I did take were of my gourmet lunch box, which I’d been ridiculously looking forward to and which surpassed all my expectations and then some. The box was massive, and the food was so so good. I also took a picture of (part of) the booksale table (by Words Worth Books), because they’d brought in Best Canadian Essays 2011 (with my essay in it!) and put it on display beside all the other festival presenters’. I am sure it sold like hotcakes, but yes, it was kind of the honour of my life to be a little old blogger up there beside some of Can-Lit’s finest. A thrill I will never, never forget.

Rumour has it that the event was a success, and they might put it on again next year. Here’s to the beginning of a fantastic literary tradition!

November 2, 2012

Where my tea rests

I don’t have a desk. In another life, I worked in a closet, but now the closet is stuffed with baby paraphernalia and there is no room for me and mine. Which isn’t bad, in fact it’s fine. For the past three years, I’ve made the western half of our couch my working home, which you’d be able to tell if you ever sat on it. The springs are shot. My seat is right beside the tall bookcase which houses authors A through H, with a table nearby to pile books and set my laptop on. Often, my husband is situated nearby too, which makes for an optimum working environment. I like it also because I get to work whilst lying down.

I don’t have a desk. In another life, I worked in a closet, but now the closet is stuffed with baby paraphernalia and there is no room for me and mine. Which isn’t bad, in fact it’s fine. For the past three years, I’ve made the western half of our couch my working home, which you’d be able to tell if you ever sat on it. The springs are shot. My seat is right beside the tall bookcase which houses authors A through H, with a table nearby to pile books and set my laptop on. Often, my husband is situated nearby too, which makes for an optimum working environment. I like it also because I get to work whilst lying down.

What I appreciate most truly, however, is the place where I rest my tea. From my Random House mug, of course, because what’s a point of a teacup if it isn’t enormous? But not so enormous that it can’t perch exactly within arm’s reach, right beside Anne Enright and Alice Thomas Ellis. I think my tea keeps really good company– the gorgeous spines of my Anne Fadiman books, and even Deborah Eisenberg. It’s always right there when I need it. But not so near within my reach that my flailing arms have ever knocked it over. Yet. Knock on (bookcase) wood.

November 1, 2012

The Elizabeth Stories by Isabel Huggan

Isabel Huggan’s The Elizabeth Stories is the book I’ve been talking about for a week now, desperate to shove it into someone’s hands so they can know, or else to encounter someone who already knows just how wonderful it is (and this has happened a lot). In terms of Canadian short stories masters, we don’t have to pick sides, but I liked this book better than any I’ve ever read by Alice Munro or Mavis Gallant. Less a novel in stories or a short story collection than a book— but then I can also reflect back on the individual stories. I think that “Sorrows of the Flesh” might be the best short story that I have ever, ever read.

Isabel Huggan’s The Elizabeth Stories is the book I’ve been talking about for a week now, desperate to shove it into someone’s hands so they can know, or else to encounter someone who already knows just how wonderful it is (and this has happened a lot). In terms of Canadian short stories masters, we don’t have to pick sides, but I liked this book better than any I’ve ever read by Alice Munro or Mavis Gallant. Less a novel in stories or a short story collection than a book— but then I can also reflect back on the individual stories. I think that “Sorrows of the Flesh” might be the best short story that I have ever, ever read.

As a bildungsroman, The Elizabeth Stories visits familiar terrain–young girl growing up in small town Ontario, constrained by convention, a misfit, confused by how the conservative society she lives in has no regard for her burgeoning sexuality. The stories were familiar to me as scenes from my own life– anger at a school-yard victim and the horrible people they drive us to be; the epic nature of childhood humiliations; the pain of not fitting in; of being misunderstood; of that impossible love for a high school teacher.

And yet, these stories surprised me at every turn, Elizabeth surprised me at every turn, for her ordinariness, for the plainness of her situation, a plainness so rarely encountered in fiction. In The Elizabeth Stories, there is no justice, no ending is tidy. Elizabeth’s parents are unbearably awful people in very subtle ways, though we’re provided glimpses as to how their characters have been shaped. Elizabeth herself does the most terrible ordinary things, we witness moments that are unbearable to watch, that leave us thinking, “Oh, no she didn’t. But of course she did!” How shocking twists are inevitable just a page later. And how many shocking twists there are in this book that so much reeks of the ordinary, the domestic, the mundane. There is a brutal, horrifying stuff going on here, and I think of this at a time when women writers are crawling out onto crazy limbs in order to be gritty, shocking, to push the limits of what we’re allowed to write about. When Isabel Huggan was doing it all the while, such brutality right here embedded into this neat little package of a book. Maybe some of us don’t have to try as hard as we think we do, or maybe the point is that not everyone is Isabel Huggan, but still.

And oh, the writing. How the ordinary is illuminated (like Lisa Moore and sock-sorting in February— turns out there is more story in a laundry basket than we ever imagined). From “Queen Esther”: “As soon as I was tall enough, my household chore on Mondays was to bring the wash in after school. It was a job I never objected to, even when in the winter my fingers ached as I pulled at the pegs on the frozen shirts and sheets. The clothes, stiff and unwieldy, would be stacked like boards in the basement where overnight they’d go limp and damp, perfect for ironing on Tuesday. The grey-blue shadows on the snow, the sky like clear rosy tea steeping darker, the creak of the lined–the only part missing in winter was the smell. In all other seasons, I buried my face in the laundry and breathed it in, the delicate aroma of virtue.”