April 24, 2013

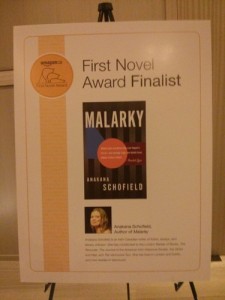

Malarky Triumphs!

Oooh, what a night! I’ve been a devotee of Anakana Schofield’s Malarky since I first read it just over a year ago now, and so it was fantastic to be in the crowd tonight as Our Woman, the book and its author finally got the credit they’ve long-deserved. So pleased that Malarky was tonight awarded the 2013 Amazon First Novel Award. Sometimes it all works out all right. And sometimes you also end up with the most mind-blowing assortment of desserts in your lap, on a plate even, ready to eat. They were as good as they looked.

Oooh, what a night! I’ve been a devotee of Anakana Schofield’s Malarky since I first read it just over a year ago now, and so it was fantastic to be in the crowd tonight as Our Woman, the book and its author finally got the credit they’ve long-deserved. So pleased that Malarky was tonight awarded the 2013 Amazon First Novel Award. Sometimes it all works out all right. And sometimes you also end up with the most mind-blowing assortment of desserts in your lap, on a plate even, ready to eat. They were as good as they looked.

April 23, 2013

Getting Ready

It is with as much relief as terror that we acknowledge that this is really happening. That after 36 weeks of us definitely thinking of getting around to performing these tasks that there is now a crib set up in our room, tiny diapers stacked next to the changing-pad, order created from the chaotic mess of our garret/closet which contains a ridiculous four-years-worth of baby and kid stuff. The baby clothes are laundered and waiting in a drawer. And the baby itself is head-down as confirmed by last week’s ultrasound and therefore I’ve not had to spend this week consulting moxibustionists. This is not to say that there aren’t a thousand things I want to/have to do before our baby arrives, but at least they don’t involve putting furniture together, matching tiny socks, or turning impossible babies. In a fundamental way, we are actually ready for the baby to come. And due to a crazy trick of nature, we’re even excited.

It is with as much relief as terror that we acknowledge that this is really happening. That after 36 weeks of us definitely thinking of getting around to performing these tasks that there is now a crib set up in our room, tiny diapers stacked next to the changing-pad, order created from the chaotic mess of our garret/closet which contains a ridiculous four-years-worth of baby and kid stuff. The baby clothes are laundered and waiting in a drawer. And the baby itself is head-down as confirmed by last week’s ultrasound and therefore I’ve not had to spend this week consulting moxibustionists. This is not to say that there aren’t a thousand things I want to/have to do before our baby arrives, but at least they don’t involve putting furniture together, matching tiny socks, or turning impossible babies. In a fundamental way, we are actually ready for the baby to come. And due to a crazy trick of nature, we’re even excited.

There wasn’t a lot of “birth preparation” going on the last time we went through this. We took the obligatory pre-natal class, but due to obvious defects in our personalities, Stuart and I just sat in the back and made sarcastic comments. And Harriet was stuck in the transverse-lie from so early on that it felt futile to make real arrangements for the natural birth we’d been hoping for. The “natural birth” itself was a choice we’d plucked out of the air without much context–it didn’t really seem possible that we’d come out of this whole pregnancy gig with something as miraculous as a baby anyway, and we were very much just going through the motions. When we were waiting for Harriet to be born, we were really just playing house.

This time however, it’s been so different, and I’ve been so much more deliberate in my choices. Even though my choices are the same, but this time I understand what they mean to me, to us. And it’s different too now that “us” is also Harriet. Having a little person with stakes in the arrival of another little person changes everything. She is also evidence that this baby is really going to happen, and our lingering memories of her babyhood make us quite aware of what we’re getting into.

“This time, it’s been different….” I keep writing this, and it should be self-evident, but the difference continues to fascinate me. It all feels a bit like Annie and Ernie McGilligan Spock and their fantastical trike ride: “In the same front yard/ Stood the same small tree;/ On the same brown table/ The same pot of tea.” And yet not the same at all. “How was it possible?/ Think of the shock…”

There is relief though this time in how much seems so different. My introduction to motherhood was such terrible time and we’ve still not quite shaken off the trauma of it all, and so I relish the idea that this time around we could make a different story. I think this was why it seemed particularly distressing last week when doubt was cast as to whether Baby was really head-down after all. And, “No way, no how,” said I. “I am not having another c-section.” For the past four weeks, I’ve been practising birthing hypnosis, and its impact became evident to me in how I responded to the potential breech situation. “I have courage, faith and patience,” I said. “This baby is going to turn. I am not going to book a c-section. I am going to go into labour. I am going to deliver this baby breech if I have to. This baby and my body know what they have to do.”

It’s quite true that I am determined that my birth story is going to be different this time. Not that the birth of Harriet was particularly troubling in itself, and recovery from c-section was remarkably easy, but I’ve told the story to myself over the past four years, it’s become clear to me that the c-section was responsible for some of the disconnect I felt from my baby after my birth. And I have gotten more angry as time as passed that I never saw her when they pulled her out of me, that I never saw her purple and sticky. She wasn’t shown to me until she’d been tidied up and wrapped in a blanket, which was only a few minutes, but I am sure I missed something terribly important in that gap. I read a copy of my operative report last week and it was fascinating (“interoperative finds: a live female”) but disturbing too that this thing had been done to me and I was so uninvolved. Unfathomable that the subject of the report was me.

(Last Tuesday when we thought Baby was breech, I was in a foul, foul mood. I’d also brought home a pamphlet from a cesarean support group that helps women spiritually heal from and grieve their c-section experiences. “What kind of bullshit is this?” I was exclaiming [at the dinner table, naturally] and my terrible husband with an evil glint in his eye said, “I think you should go.” I protested and he shrugged calmly: “You’ve been grieving your c-section for four years,” he said. My fist shook at the ceiling. “I am allowed,” I told him, “to grieve my c-section and find c-section support groups totally stupid.” I am a complicated person, and therefore this is my right.)

Harriet’s birth was booked two weeks before it happened, and it baffles me now that I opted for surgery so readily (though not before trying an ecv so there was a bit of effort on my part). But I think that my scheduled caesarean brought with it a bit of relief, some assurance, less of the great unknown. I’ve been sorry ever since that I never got a chance to go into labour though, and I’ve never shaken the feeling that I missed out on something monumental in my own birth as a mother. I went into her birth uttering inane phrases like, “The baby’s in charge,” but I never really meant it. If motherhood has taught me anything, it’s that I can out-stubborn the most unruly toddler. I was a fool to pretend that I could give in so easily, and this time I refuse to. I think I also said things like, “What matters is the result of a healthy baby and not how baby arrives,” which is a very easy thing to say if your body is not involved with baby’s arrival. Birth happens to Mother as much as Baby and to suppose that the mother’s experience somehow matters less is so completely insulting. This is also the thing that disappointed people say, as I know from experience, and also because my friends who’ve had amazing births will tell you straight that how their babies arrived matter to them very, very much. And I want to know what that’s like.

As much as one can ever prepare for something as unknown and unpredictable as childbirth, I feel as though we’ve made a valiant effort. Daily hypnosis practice, so much reading, the 3 hour pre-natal refresher we did last night which was so fantastic. I am very excited about the chance to try something I feared would always be out of reach to me. I can’t quite believe it really that anything could be so straightforward, and while I know that there is nothing straightforward about birth (just as I know that Harriet and I would have died had I not had access to a c-section with her in a transverse lie, and I know that these things don’t matter to some people as much as they’ve turned out to have mattered to me, which is just fine), I feel confident and supported in this being a road I can travel down.

And I now am excited and hopeful to discover just where that road leads.

April 21, 2013

Cottonopolis by Rachel Lebowitz

In Cottonopolis, Rachel Lebowitz both imagines and recreates the global trinity that was created by the 19th century cotton industry–in the American South where the cotton was grown by slave labour, in Lancashire England where the cotton was produced in mills with their belching chimneys and inhumane working conditions, and in India whose own textile trade was violently supplanted by the introduction of English imports. Through a series of prose poems and found poems, Lebowitz draws tight the lines between these distant places, their connections to lives lived locally and globally, and the connections between economics, industrialization, and story-telling. She plants seeds of connection between those nineteenth-century factories “[u]ntil the 1980s is a wasteland of old chimneys. Until the clothes are made in China…”. This is not a story as distant in place and time as it might seem.

In Cottonopolis, Rachel Lebowitz both imagines and recreates the global trinity that was created by the 19th century cotton industry–in the American South where the cotton was grown by slave labour, in Lancashire England where the cotton was produced in mills with their belching chimneys and inhumane working conditions, and in India whose own textile trade was violently supplanted by the introduction of English imports. Through a series of prose poems and found poems, Lebowitz draws tight the lines between these distant places, their connections to lives lived locally and globally, and the connections between economics, industrialization, and story-telling. She plants seeds of connection between those nineteenth-century factories “[u]ntil the 1980s is a wasteland of old chimneys. Until the clothes are made in China…”. This is not a story as distant in place and time as it might seem.

Many of the poems in Cottonopolis are classified as “Exhibits”, extrapolations of nursery rhymes, historical record, images, maps and items everyday and otherwise. Some echo the voices of those whose lives were made or broken by the cotton trade. The collection’s notes at the end of the book provide context and further explanation for what the poems themselves represent, and they add fascinating weight to this creative work and its stories.

But most remarkably for this book that uses language to build a museum is that the language itself is easily and unabashedly the work’s most remarkable aspect. I love the stories here, the history, but I can’t help but catch my mind on a line like “The trill of the/ robin, the trickle of the rill.” Or my favourite poem in the collection, “Exhibit 33: Muslin Dress” which turns language inside out in order to sew the whole world up into a tidy purse: “Here are the railway lines and there are the shipping/ lines. Here’s the factory line. The line of children in the/ mines. The chimney lines. There is the line: from the/ cotton gin to the Indian.”

April 17, 2013

Not just fine

“But something about new motherhood also darkened my worldview and made the thought of those cries more threatening. This is where you may be wondering if I’m just talking about post-partum depression, but the struggles I have in mind are unlikely to raise any significant red flags at the six-week check-up. And while, being raised in a family of psychologists, I certainly asked myself whether I might have PPD, I generally didn’t find that line of questioning helpful.

Don’t get me wrong—it’s an important question that we should keep asking ourselves and each other, and we should seek treatment unapologetically if the answer might be yes. But the problem with that question as our primaryapproach to the struggles of new motherhood is that it suggests that the post-partum experience itself is just fine, unless of course you have a legitimate clinical illness that distorts your perception of it. And the post-partum experience is not just fine. It is immensely, bizarrely complicated. It is, at various times and for various people, grueling and joyful and frightening and beautiful and disorienting and moving and horrible. There’s a lot going on there that will never make its way into the DSM V.”

-from “Before I Forget: What Nobody Remembers About New Motherhood” by Jody Peltason, whose standout line was “” We thought it would be sitcom-style hard.” Yes, indeed!

April 16, 2013

Upside down

I am quiet this week, mostly because I am reading Meg Wolitzer’s The Interestings and that’s all I really want to do. What I don’t want to be doing is fretting about Baby being breech, but alas this seems to be my fret of the moment. I’m waiting for an ultrasound that will confirm either way. At least Baby is not transverse ala Harriet, which means the ending of this story has yet to written. Fingers crossed, but I’m pulling out all the stops this time, which is to say that I might discover what moxibustion is, and anything else that could possibly help turn the wee one. And if baby is breech, I will then be really concerned about why its bum is so head-like in its composition. What kind of anatomy is that?

I am quiet this week, mostly because I am reading Meg Wolitzer’s The Interestings and that’s all I really want to do. What I don’t want to be doing is fretting about Baby being breech, but alas this seems to be my fret of the moment. I’m waiting for an ultrasound that will confirm either way. At least Baby is not transverse ala Harriet, which means the ending of this story has yet to written. Fingers crossed, but I’m pulling out all the stops this time, which is to say that I might discover what moxibustion is, and anything else that could possibly help turn the wee one. And if baby is breech, I will then be really concerned about why its bum is so head-like in its composition. What kind of anatomy is that?

In good news, I’ve worn capri pants and sandals two days in a row. Not entirely sensibly, but altogether happily. And at least the sun is shining.

April 14, 2013

The Douglas Notebooks by Christine Eddie

I was attracted to The Douglas Notebooks by Christine Eddie first because it is a beautiful object, a small and lovely book whose cover is adorned with blossoms and brambles that wind their way throughout the book entire. I was attracted to it also because the book in its original French had been the recipient of several literary awards, and French Quebec fiction is such unexplored territory for me. I welcome Goose Lane Editions publishing this English translation (by Sheila Fischman), widening my literary landscape as they did by publising Australian lit-award winner Night Street by Kristel Thornell last year. What a service to English Canadian readers to bring us these books we mightn’t encounter otherwise.

I was attracted to The Douglas Notebooks by Christine Eddie first because it is a beautiful object, a small and lovely book whose cover is adorned with blossoms and brambles that wind their way throughout the book entire. I was attracted to it also because the book in its original French had been the recipient of several literary awards, and French Quebec fiction is such unexplored territory for me. I welcome Goose Lane Editions publishing this English translation (by Sheila Fischman), widening my literary landscape as they did by publising Australian lit-award winner Night Street by Kristel Thornell last year. What a service to English Canadian readers to bring us these books we mightn’t encounter otherwise.

The Douglas Notebooks is branded “a fable”, which I’ll admit did not attract me to the book. I like my novels in the here and now, thank you very much, peopled by people instead of scurrying creatures. But “fable” here is a label loosely applied (for example, there are no talking rabbits, and apparently fables are meant to have morals but I’m not sure what the moral is here), and I often find that any novel I read in translation has an element of “fable” about it anyway, or at least sone kind of otherness. Here is not the novel in the shape I know it, I mean, and they always seem a little bit otherworldly. I have to judge a novel in translation on its own basis as well, and not based on what I understand “the novel” to be in my own limited experience of the form.

Which is not to say that The Douglas Notebooks is difficult to approach as a reader, or that I had to work hard to enjoy it. On the contrary, it was an easy book to slip inside, a fast and lively read. It seems out of place and out of time, situated in a village that doesn’t appear on a map and that for most of the book remains out of touch with progress and the rest of the world, though there are indications–the telltale tattoo on the schoolteacher’s arm, for example, which situates the book inside history. It’s the story of Romain, the son of a rich family who escapes them as soon as he can for a solitary life in the woods where he can be free. He enounters Elena, who has fled her violent homelife and made an apprenticeship with the village “pharmacist”, learning from her natural and herbal remedies for illness. But Elena leaves the pharmacist to make a life in the woods with Romain, who has since been remamed Douglas, for the fir tree. When Elena becomes pregnant, the couple feels as though their dreams will be fulfilled, and that with their child they will create a new world and a new way of life far removed from the trappings of society. But plans go wrong, and the result is heartbreak.

Brought into their fold are the local doctor who had loved Elena from afar, and the schoolteacher who had always been an outsider in the community, as well as a tamarack tree with mythical properties. In the centre of it all is the baby Rose, and the love that is wrapped around her like the brambles on the novel’s cover, both protection and a trap.

The Douglas Notebooks is a peculiar book, a tricky thing, and I’m not surely I’ve completely made sense of it yet. Why it’s a fable, for example, and what it means that this very rural book with all its natural elements (including, most wonderfully, a reverence for trees) is sort of structured cinematically, with the novel broken into sections with titles like “Wide Shot”, “Fast Motion” and “Close-Up” and even “Credits (in order of appearance)” as the book’s conclusion. But the unanswered questions are not unsatisfying, rather they underline for me in this slim and quiet book are just depths I haven’t plumbed yet.

April 12, 2013

Stick Figure Families and the Punch List

When I was pregnant with Harriet and in my third trimester, I started creating something called a “punch list”. Let’s just say I was not the picture of serenity. And as I move toward the final month of this pregnancy, the same old rage is taking hold, and today I’ve channelled it into a post at Bunch about the inexplicable nature of stick figure family car stickers. And I really do think that “fucking Fido Dido” is the best line I’ve ever written. Dare to argue, and I’ll likely punch you.

April 11, 2013

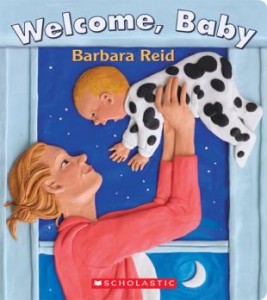

A Book for Baby's Library

I bought a book for the new baby this week, the very first book of this baby’s own. It’s Welcome, Baby, a gorgeous new board book by Barbara Reid that I’m sort of thinking was written just for our new baby. If you know Barbara Reid’s illustrations, then you already know the book is beautiful–I’m in love with the quilt on the title page. “Welcome, baby, welcome!/ All the world is new,/ And all the world is waiting/ To be introduced to you…” the book begins, with a picture of a couple holding their new little one, a tree and robin just outside the window. And what I really love is that older siblings are a part of this welcome too, and so Harriet gets to point to the picture of Big Kid and Baby playing trucks, and saying, “That’s me!” of the former, and so too with the picture of the siblings splashing in the paddling pool. It ends, “We’ll hold you close,/ And let you fly.” which is just perfect, and the whole trick of being a parent really. I look forward to reading this one over and over, and in delighting as new tiny hands learn to grasp its pages.

I bought a book for the new baby this week, the very first book of this baby’s own. It’s Welcome, Baby, a gorgeous new board book by Barbara Reid that I’m sort of thinking was written just for our new baby. If you know Barbara Reid’s illustrations, then you already know the book is beautiful–I’m in love with the quilt on the title page. “Welcome, baby, welcome!/ All the world is new,/ And all the world is waiting/ To be introduced to you…” the book begins, with a picture of a couple holding their new little one, a tree and robin just outside the window. And what I really love is that older siblings are a part of this welcome too, and so Harriet gets to point to the picture of Big Kid and Baby playing trucks, and saying, “That’s me!” of the former, and so too with the picture of the siblings splashing in the paddling pool. It ends, “We’ll hold you close,/ And let you fly.” which is just perfect, and the whole trick of being a parent really. I look forward to reading this one over and over, and in delighting as new tiny hands learn to grasp its pages.

April 10, 2013

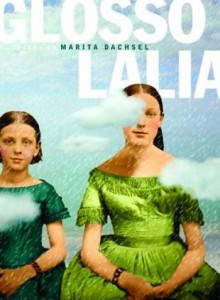

Glossolalia by Marita Dachsel

Marita Dachsel is a friend, and I was already inclined to like her new book Glossolalia because I’ve got a thing for obscure historical figures/stories whose voices are resurrected via poetry. In Glossolalia, the stories belong to the 34 polygamous wives of Joseph Smith, founder of the Mormons, though Dachsel is careful to point out that her book is not meant to be a biography or a historical work. Rather, as Sharon McCartney explained with her Laura Ingalls Wilder poems, “the voices, the characters and the details are vehicles, a way to say what I want to say.”

Marita Dachsel is a friend, and I was already inclined to like her new book Glossolalia because I’ve got a thing for obscure historical figures/stories whose voices are resurrected via poetry. In Glossolalia, the stories belong to the 34 polygamous wives of Joseph Smith, founder of the Mormons, though Dachsel is careful to point out that her book is not meant to be a biography or a historical work. Rather, as Sharon McCartney explained with her Laura Ingalls Wilder poems, “the voices, the characters and the details are vehicles, a way to say what I want to say.”

Glossolalia is a curious, wonderful book, in which a “self-avowed agnostic feminist uses mid-nineteenth century Mormon America as a microcosm for… universal emotions…”. Through Smith’s wives, each one with her own name, point of view and distinct voice, Dachsel explores ideas about love, marriage, pregnancy, motherhood, jealousy, domesticity, sex, trust, and betrayal. While the poems themselves are united by their representation of the voices of Smith’s wives, their styles and approaches are remarkably diverse, some written with formality and great distance, others more ribald and contemporary in tone. Apart from a few (often negative) examples, there is no sense of connection between these women, the poems showing their experiences of the world to be remarkably disparate, complicating tidy ideas of sisterhood. Dachsel’s wives are less a chorus than a cacophony, a crowd of dissonant voices, each shouting to be heard above the others.

But hear them, we do. The wives each emerge as distinct, aware, embodied, and it is the smallness and closeness of poetry (as well as their poet’s talent) that brings them so to life.

April 9, 2013

Life After Life by Kate Atkinson

I never got over Behind The Scenes at the Museum, Kate Atkinson’s first novel which won the Whitbread Award in 1995 (“‘A 44-

I never got over Behind The Scenes at the Museum, Kate Atkinson’s first novel which won the Whitbread Award in 1995 (“‘A 44-

I was ecstatic to learn, however, that her new novel would be a return to straightforward literary form. Well, not straightforward exactly, because Atkinson makes a point of taking form and exploding it into a million pieces. There is nothing at all straightforward about Kate Atkinson’s fiction, and what has always delighted me most about her literary novels is how covertly they’re all detective novels as much as Case Histories et. al. That there is ever such mystery at the core of her books–ghosts and dead bodies and things unexplained.

What is explained, however, what most readers will know because they start reading is that Life After Life comes with a gimmick. Think Sliding Doors and The Post-Birthday World, though not with parallel lives exactly but an array of them instead, strung together like a garland of paper chain dolls. Ursula Todd comes to life, then she dies, and then she’s born again and again, after each death returned to her beginnings, that night in 1910 when she comes into the world during a snowstorm. But then this isn’t even really the point, and here’s what allows Kate Atkinson to defy the bounds of genre: the point of this book isn’t the fantastic, but that it was written by Kate Atkinson and she’s wonderful.

I began this book with a strange sense of deja-vu (which was funny in itself because deja-vu is what it’s all about) because it reminded me so much of AS Byatt’s The Children’s Book, which I read four years ago when I was even more ridiculously pregnant than I am right now. The same depiction of the Edwardian middle-class family in a rural idyll (Todefright Hall vs. Fox Corner) with more children that it knows what to do with, some of whom are suspected to not really belong. And the banker father, fairy story references, connections to Germany. Both novels are setting out to do vastly different things, but in Atkinson’s I sensed an echo of the Byatt, and I loved that.

Ursula is born, Ursula dies, and then Ursula is born again, and while Atkinson does not explicitly spell out Ursula’s consciousness of her situation, her actions portray a dawning awareness that there is more to her life than just this one. This awareness manifests as strange sense of dread when she is young, that keeps her firmly on the beach where she’d drowned just a short lifetime ago. Her plight turns comical as she attempts numerous time to prevent her family’s maid from attending WW1 victory celebrations at which she’ll encounter the Spanish influenza and go on to infect Ursula and her beloved younger brother. Ursula eventually resorts to pushing her down a flight of stairs (thus saving the day), and ending up on a psychiastrist’s couch. Her parents are concerned with her oddness, her propensity for deja-vu.

Ursula comes up with clever ways of avoiding her previous mistakes, managing to make it through the 1920s and ’30s and only dying a handful of times. She falls in love, she has affairs, she stays single, she suffers a disastrous marriage, she is disgraced, she triumphs, she falters, and then is born again, determined to make her way. The connections and disconnections between Ursula and her siblings are particularly compelling. World War Two, however, proves to be an enormous impediment to Ursula’s lifeline. Again and again, she finds herself killed in the Blitz, and when she finally manages to skirt her particular explosion, other complications present themselves. Her fate seems determined to find her no matter how she goes out of her way to avoid it.

There is texture to a book like this, and the pleasure of seeing secondary characters from a wide variety of angles–Ursula’s mother in particular whose role in the novel’s conclusion was ingenious. Life After Life is a long book, as befitting a life lived over and over again, and I savoured its slowness, the returns to where I’d been before, places and people I was happy to revisit. I appreciated the specificity of its detail, the brilliance of its writing, its genre-blurring, its daringness in reframing the shape of a narrative, and yes, this is Kate Atkinson, so there is going to be that too.