May 26, 2013

Canary by Nancy Jo Cullen

Not the most succinct review, this one. I read Nancy Jo Cullen’s Canary for enjoyment rather than critical analysis, mostly because I’m 40.5 weeks pregnant, and who wants to analyze critically whilst crawling on the floor (and incidentally, I’m on my knees and elbows as I type this)? But the book left such an impression on me that I have to write about it. I loved these stories of families and volcanic eruptions, hitching rides and kissing cousins. In “Ashes”, a teenaged girl’s family falls apart while she and her dad are out practicing driving (and we meet the girl again decades later in the story “Eddie Truman”, whose links are subtle and touching). A marriage of convenience is the subject of “The 14th Week in Ordinary Time”, in which a gay holy roller takes up with a singer with a past she’s more than happy to escape. “Regina” begins with the line, “I wasn’t in love with the kleptomaniac but he was a good dresser” and it just goes from there. “Valerie’s Bush” is about a Brazilian wax and a rock through a window. “Canary” is one of a few stories about drivers and passengers, this one about an embarrassing mom chauffeuring her teenage son on a date. Another is “Passenger”, about a widower driving a teenage girl across the country as he grapples with the loss of his wife who has gone to a heaven he doesn’t believe in. In “Happy Birthday”, a woman flees her mother’s 83rd birthday party and her asshole of a partner, bolting to freedom. I loved “This Cold War” because I’ve got a thing for 1989. And oh my goodness, “Big Fat Beautiful You”, what a powerful way to finish this collection, connecting past and present, as a middle-aged woman testifies to who her sister was and who she is now: “Caroline is like one of the comets that travel fast enough to enter and leave the solar system with almost no attention. I guess I am the witness who noticed the collision and subsequent disintegration of the marvellous light.” A story like a Bruce Springsteen song, if Springsteen were a woman–I love that. There is humour here, engrossing narrative, and wonderful, wonderful writing.

Not the most succinct review, this one. I read Nancy Jo Cullen’s Canary for enjoyment rather than critical analysis, mostly because I’m 40.5 weeks pregnant, and who wants to analyze critically whilst crawling on the floor (and incidentally, I’m on my knees and elbows as I type this)? But the book left such an impression on me that I have to write about it. I loved these stories of families and volcanic eruptions, hitching rides and kissing cousins. In “Ashes”, a teenaged girl’s family falls apart while she and her dad are out practicing driving (and we meet the girl again decades later in the story “Eddie Truman”, whose links are subtle and touching). A marriage of convenience is the subject of “The 14th Week in Ordinary Time”, in which a gay holy roller takes up with a singer with a past she’s more than happy to escape. “Regina” begins with the line, “I wasn’t in love with the kleptomaniac but he was a good dresser” and it just goes from there. “Valerie’s Bush” is about a Brazilian wax and a rock through a window. “Canary” is one of a few stories about drivers and passengers, this one about an embarrassing mom chauffeuring her teenage son on a date. Another is “Passenger”, about a widower driving a teenage girl across the country as he grapples with the loss of his wife who has gone to a heaven he doesn’t believe in. In “Happy Birthday”, a woman flees her mother’s 83rd birthday party and her asshole of a partner, bolting to freedom. I loved “This Cold War” because I’ve got a thing for 1989. And oh my goodness, “Big Fat Beautiful You”, what a powerful way to finish this collection, connecting past and present, as a middle-aged woman testifies to who her sister was and who she is now: “Caroline is like one of the comets that travel fast enough to enter and leave the solar system with almost no attention. I guess I am the witness who noticed the collision and subsequent disintegration of the marvellous light.” A story like a Bruce Springsteen song, if Springsteen were a woman–I love that. There is humour here, engrossing narrative, and wonderful, wonderful writing.

May 23, 2013

Date Due

The honeymoon has ended, that wonderful period of pre-baby motherhood in which it’s imperative to be taken out for afternoon tea and be administered lots of fragrant baths. Now instead of relaxing and taking care of myself, I’m given instructions like, “Try crawling around the carpet for half an hour–while watching TV or listening to music. It is good exercise as well as good for the baby’s position!” And it’s only a short slide from here to the point where I’ll be having trouble breastfeeding and crazy people on online forums will instruct me to refrain from eating anything but white rice, while I lock myself in a darkened room for a fortnight hovering naked over my colicky child in order to discourage it from nipple confusion. At least this time, I know what to expect.

Today is my due-date, which I’m calling my date-due because I’m better at libraries than being patient. But what I’m better at than anything else is jumping straight to worst-case scenarios, which is why I decided that since baby shows absolutely no sign of imminent arrival (or even un-imminent arrival) that baby was never going to arrive at all. I’ve since been reassured by enough stories of babies failing to be engaged who managed to be born anyway that I am no longer fretting about booking a c-section at 42 weeks. I’ve had a hunch all along that our baby was going to be born on the Barbara Pym Centenary anyway, (June 2, but you already knew that) and I’m becoming convinced that this is really the case. I’m also sure that my bout of stomach flu at the weekend made the baby reluctant to make an entrance to the world, and now that I am feeling much better and energetic again, I am content to wait until baby decides that it’s time.

As I crawl around the carpet on my hands and knees, of course. There cannot be enough of that.

May 21, 2013

Dance, Gladys, Dance by Cassie Stocks, 2013 Leacock Medal Award-Winner

In many ways, Cassie Stocks’ Dance Gladys Dance is the kind of book that tends to win the Leacock Medal for Humour (unlike The Sisters Brothers, which took the prize in 2012 and stands out for its gory darkness). It’s a folksy, Sunshine Sketches, Vinyl Cafe kind of book about good people and their weathered porch steps, about the eccentric woman next door who is devoted to her cat. There is a life-affirmingness to the narrative, coupled with biting lines that made me laugh out loud.

In many ways, Cassie Stocks’ Dance Gladys Dance is the kind of book that tends to win the Leacock Medal for Humour (unlike The Sisters Brothers, which took the prize in 2012 and stands out for its gory darkness). It’s a folksy, Sunshine Sketches, Vinyl Cafe kind of book about good people and their weathered porch steps, about the eccentric woman next door who is devoted to her cat. There is a life-affirmingness to the narrative, coupled with biting lines that made me laugh out loud.

In one fundamental way, however, Stocks’ novel stands out from the other winners from over the last 66 years, or at least the other winners save the paltry five (5!) in the crowd which also happened to be books written by women. Last year, I kicked up a fuss when some of the funniest books by women weren’t included in the mix, and I was even more annoyed when the lone male writer on the shortlist ended up taking home the prize. And so this year when Cassie Stocks was awarded the 2013 Medal, I felt I had a responsibility to show my support for the book and its acclaim by buying it and reading it. Not the most arduous gesture either–how hard is it to read a book that’s funny?

It’s not all sunshine in Dance, Gladys, Dance. The novel deals with parental estrangement, prostitution, drug abuse, loneliness, and the undermining of women’s work and women’s art by society at large. Frieda Zweig is fed up with the whole thing and has decided to abandon her artistic dreams altogether. She has come home to Winnipeg with a new goal for herself–to hang up her paintbrushes for once and for all and learn how to live like an ordinary person instead. And though we’re rooting for Frieda right from the start, we’re quite aware that being ordinary is the one thing in the world she’s not capable of.

She answers an ad in the paper for an antique photograph for sale. “Gladys doesn’t dance anymore,” it says. “She needs the room to bake.” Seeing parallels between Gladys’ story and her own, she goes looking for Gladys only to discover there is no Gladys at all, but instead an elderly man with a room to rent. This situation works out quite conveniently for Frieda, and then Gladys starts showing up–it turns out she’s a ghost with a lesson to impart from her own experiences a century before, and there is something she wants from Frieda as well in exchange. In the meantime, the local arts centre is set to be closed and the community must rally around to save it, plus Frieda’s best friend has become a utensil thief. The woman next store is a compulsive crocheter, Frieda’s ex-boyfriend Norman (millionaire heir to a porn dynasty) has come to woo her back, bringing along his mother who’s busy reading everyone’s aura. And what of the homeless girl who builds boxes covered in tampon ads, and the drug addicted screenwriter holed up in a divey hotel who’s a Hollywood smash and doesn’t even know it? And Gladys herself? Does she ever get to dance?

Obviously, there is a whole lot going on here, and it’s often a bit too much, however amusing. The novel’s construction is more haphazard than precise, more elaborate and teetering towers than the firm foundation required to adequately address the subject matter at hand. We skim the surface of these stories, which seem more like sketches, and the people are more caricature than character much of the time. So yes, I’m criticizing a novel that’s just won a prize for humour for not being serious enough, which is a bit rich, of course, but I point it out only because the novel is reaching for depth but doesn’t quite manage to get there and there were times I wished it would.

Other times, however, I was quite content with Gladys as she is–light, smart and feminst, a stand-out in the crowd. Cassie Stocks demonstrates that the funny sisters are doing it for themselves.

May 19, 2013

Author Interviews @ Pickle Me This: Samantha Bernstein

I was introduced to Samantha Bernstein once at an event at the Toronto Women’s Bookstore not long before her memoir Here We Are Among the Living came into the world. When her book was nominated for the BC National Award for Canadian Non-Fiction, one of just three books written by women on a long-list of ten, I knew I had to read it, and it turned out to be one of my favourite books of 2012.

I was introduced to Samantha Bernstein once at an event at the Toronto Women’s Bookstore not long before her memoir Here We Are Among the Living came into the world. When her book was nominated for the BC National Award for Canadian Non-Fiction, one of just three books written by women on a long-list of ten, I knew I had to read it, and it turned out to be one of my favourite books of 2012.

Yes, this is a memoir written by Irving Layton’s daughter, but Bernstein’s literary lineage was less interesting to me than the Toronto she writes about, and her stories of what it was to come of age at the turn of the millennium. I came away from the book wanting to expand on the questions it posed, and so I was very pleased when Bernstein agreed to engage in an email conversation with me.

The following interview was conducted over the past five months, which seems like a long time, but considering it took place between two pregnant women with rich and busy lives, it’s really a wonder that we pulled it off at all.

KC: Did you always know that your memoir was going to be in epistolary format? Why was it important that it was? And were the emails in your book based on actual correspondence?

SB: Yes, I knew from pretty early on that the book would be in emails. I first started working on it during my undergrad in creative writing at York, and my prose assignments started coming out as emails. The idea of writing a book was like a pair of sunglasses I couldn’t take off, but which I felt quite stupid about wearing—Who am I trying to be? and all that. My world at the time was completely tinted by those damn glasses (which, as my mom would tell you, I was super pissed off about much of the time). That need to transcribe everything got funneled into my correspondence with my friends Eshe and Joe; so writing in emails was at first just a less intimidating way to write, because it was familiar and because they presuppose an interested audience.

In my last year of university I read The Sorrows of Young Werther, Goethe’s epistolary novel that sparked rebellion in the hearts of his contemporaries. Werther’s letters, at first, just seem ridiculously whiny and self-indulgent (as twenty-somethings are apt to sound…), but as we discussed the book, the self-narration began to take on a broader significance. The intensity behind Werther’s writing is fueled by the fears of youth, fears of being turned into something you despise, of betraying ideals, of failing to properly appreciate or capture the beauty you are experiencing. And as I learned more about the epistolary form, I liked its history of social engagement and criticism, its continual probing of moral and ethical questions. I felt like it would make sense for this book to be in that tradition. Especially because, as it appeared the book would have to be a memoir, I thought that the epistolary concern with subjectivity—its political implications, its distortions and narcissism—would at least be a formal recognition of the problem of writing about one’s self.

The book is based on actual correspondence, but the letters are almost entirely made up. Some lines are direct from emails I’d sent to Joe and Eshe, and certainly the correspondence we’d had helped me to remember what was going on at the time, and what we’d been thinking about. Thoughts and images from our emails got reworked into the book. I’d also been gathering moments and things people said in notebooks for years. I’ve been surprised, though, at how many people think I just printed out my hotmail folder. If only! But I’m glad the emails are believable. It was hard, sometimes, to keep my late-twenties self from editing my early-twenties self into a less obnoxiously naive/enraged person than I was.

The book is based on actual correspondence, but the letters are almost entirely made up. Some lines are direct from emails I’d sent to Joe and Eshe, and certainly the correspondence we’d had helped me to remember what was going on at the time, and what we’d been thinking about. Thoughts and images from our emails got reworked into the book. I’d also been gathering moments and things people said in notebooks for years. I’ve been surprised, though, at how many people think I just printed out my hotmail folder. If only! But I’m glad the emails are believable. It was hard, sometimes, to keep my late-twenties self from editing my early-twenties self into a less obnoxiously naive/enraged person than I was.

KC: How does email change the epistolary format? Granted, your emails aren’t so cyberish—no emoticons and LOLs. But I imagine the immediacy makes a difference. Does email offer the epistle a boost or does it reduce it?

SB: Oh, that’s a good question! I think it could do both, depending on the correspondents. It would be an interesting study to compare the language in classic epistolary and in what Michael Helm cleverly called e-pistolary novels. Both email and traditional letters express a captivation with the present moment, a need to communicate it to someone who will understand. When the first epistolary novels were being written, the postal system was the amazing new technology! But the immediacy of email does heighten the sense of youthful urgency so often present in the epistolary form; I wanted to capture the intensity of letting those thoughts spill out, usually late at night, knowing my friend would wake to see them, and that I might have a reply by the next night. An email correspondence can feel more like a conversation, I think, which opens interesting possibilities.

When I was twenty, in 2001, email was still a relatively new thing. I don’t think the word emoticon existed yet. We got our first computer when I was fifteen, and I got my hotmail account when I was about eighteen (the one I still have, whose stupid address can be explained by this fact). I’ve often mused with people my age about being the last generation to remember life before the internet, and it may be that our emails reflect this, and cling to the conventions of letter-writing. I also tend to be kind of stodgy about language —I feel like words, not pictures or acronyms, should be doing the work (although I’m not against a smiley face now and again…) But I’m sure there are people are using txt speak and such in creative and interesting ways that will ultimately help to perpetuate the epistle.

KC: What are the connections between your academic self and your writer self? Do your projects tend to overlap and how do they inform one another?

SB: In some ways I feel that academic and non-academic creativity support each other—for instance, I read the wonderful poet Gwendolyn Brooks for a course, and then wrote a sonnet cycle to her. I really felt this interaction as I was editing the book. My doctoral dissertation deals with the ethics of aestheticizing poverty, which is also a strain of the memoir, and the academic thinking helped to structure my edits and bring that theme out more clearly.

As a middle-class person interested in social justice, it’s important, I think, to be aware of how we approach and express our desires to help. When I was younger, this idea was tied up with a lot of frustration around whether my ideals or my friends’ were in any way useful or if they were simply aesthetic choices. I was especially racked by this question because of being raised in the residue of the Baby Boomers’ youth culture, which was a social revolution largely enacted through identity—now a profoundly commercialized aesthetic of “personal freedom,” “rebellion” etc. That was really the question that spawned Here We Are—what happened to the anti-materialist, egalitarian youth movements of the sixties? Were they ever really that? Or was there something inherent in those movements that resulted in the present culture that sells cars with Jimi Hendrix songs (or more recently, Keith Richards hocking Louis Vuitton)? So I did a Master’s at York that allowed me to research youth subcultures, to see how European and North American youth have historically expressed their dissent, and how these traditions intersect with epistolary and life writing. That program at York was amazing luck—I got grants, and so was able to spend the second year of the Master’s basically just writing. A dream, really.

I do feel sometimes, though, that I should choose between academia and literature. Although there are amazing people like Priscila Uppal who gracefully balance the two worlds (and I owe a lot to her teaching), you often hear that it’s one or the other. There are writers like, for instance, Camilla Gibb, who I heard was accepted into some amazing doctoral program and turned it down to write full-time. I worry there won’t be time to do it all, especially now as Michael and I are expecting our first child in the summer. That said, I know I’m not the big-time academic type. I’m not going to be moving around the country for the next ten years in search of tenure. I love teaching—I really still do (most of the time) believe that if you can incite some curiosity in a couple of students, you’ve done a valuable thing. There are so many good and important jobs that help people, for which I am in no way qualified, and teaching is one of the very few professions in which the skills I have can be put to good use. So I just hope to have the privilege of doing that, and continuing to research stuff— because I really like sitting down with a book and a pen, and underlining sentences, and thinking about what I might say about them. And I’m hoping that sometimes that saying will come out in a literary way.

KC: Speaking of youth cultures, that early-twenties self that you document in your book is actually quite a fashionable figure in our pop-culture at the moment, though what I really appreciate about your book is that the young self is a starting point, something to grow (up) from rather than to fetishize in and of itself. Youth is certainly worth examining (and I remember how profound everything seemed when I was 21, how strong was the urge to record every atom as it fell) but for many women, our early twenties are also ourselves at our worst, our most loopy and unhappy. So much gets figured out in the decade that follows, no matter how confused we remain into our 30s. And so I wonder what kind of a feminist gesture is it that society (I’m thinking books and TV shows lately—primarily the show Girls which I can’t bear to watch, fearing it will strike too close to home, reminding me of a self whose existence wasn’t as profound as she imagined she was…) is so focused on the moments before women finally get it together? Can this really be useful?

SB: This is a super interesting question, Kerry. I think it’s really true and important to point out that one’s twenties, exciting as they can be in many ways, are also this weird half-formed time in which one feels far more mature than a few years earlier (high school feels like elementary school in its contained simplicity) but is still essentially blundering around in a miasma of unexplained desires and fears (like, a thicker miasma than in later life…). I was just talking with Joe about this yesterday: how we didn’t know anything in our twenties—and yet, and yet… thinking of how we knew enough to hold onto this friendship despite geographical distance and all the uncertainty of those years, I said we were starting to know something about what we needed to be what we wanted to be.

And maybe that’s what makes this moment such a rich one to represent: we want to capture the sense of self germinating. We’re developing into some form of ourselves that can actually be carried forward, consciously, into our future lives. We are, in many cases, expressing our beliefs very strongly and at least trying to understand them, which, I think, differentiates this process from what happens in our teens, when we start believing things passionately, or identifying with things passionately, but utterly uncritically. In our twenties we start adhering—sometimes just as absurdly—to a critical framework for our actions. The blunders and insights this generates often make for good art.

There was an article in the January 13 New Yorker by Nathan Heller, which I thought was rather lovely on the topic of the twenty-something. He observes the basic continuity of depictions of this age despite recent studies on how current social and economic factors are determining the ways people experience their twenties. He compares a bit of dialogue from Fitzgerald’s 1920 novel This Side of Paradise with a bit from our present Girls, which amazingly demonstrates the continual concern with one’s own mind, with anxiety and self-doubt and how we navigate these in our relationships. Reading Heller’s article made me both happy and slightly sheepish about my book. Sheepish because I am yet another “[a]ble-bodied, middle-class [North] American” (67) documenting the “thrilling sense of nowness” (71) that characterizes the twenties for so many people in that category. Happy, though, to be in this tradition of youths of the modern world—to have documented coming of age in this particular corner of the world that hasn’t been much documented yet, and is interesting in its specificity and its connection to other times and places. And because I captured the wonder of those years as best I could, and am glad to have those moments stashed away.

So to answer your question… I think all good writing is potentially useful and all bad writing potentially harmful. I think art that depicts women in their twenties as hot messes might contribute to dialogues about everything from mental and sexual health to career choice and motherhood. I think, though, that there is a fascination with the seamy and the broken in this society, and that stories about women in harmful circumstances are perhaps more common than is quite helpful. This fascination is a central aspect of my doctoral work, because there’s an old and very interesting aesthetic tradition to our desire to make degradation and suffering into art. We should, I think, look carefully at this desire, because I do believe that art has moral implications, and if we’re satisfied with only the messed-up twenty-something girls, without signs of their growth (See Nussbaum on “Girls” ) that just indicates that we, as a society, have a lot more growing up to do.

KC: With that “thrilling sense of newness” you document, you were on to something though, and it wasn’t all in your head. Reading your book, I was struck by how you’d documented a really pivotal time in the history of Toronto, a burgeoning sense of urbanism and civic awareness among a certain class/demographic of downtowners who were made to feel as though they had a say (or deserved one) in how the city was being shaped around them. (Edward Keenan documents the same thing through a less personal filter in his new book Some Great Idea: Good Neighbourhoods, Crazy Politics and the Invention of Toronto.) Did you have a sense as you wrote Here We Are Among the Living that you were writing a Toronto book? What role does the city play as a character in your story?

KC: With that “thrilling sense of newness” you document, you were on to something though, and it wasn’t all in your head. Reading your book, I was struck by how you’d documented a really pivotal time in the history of Toronto, a burgeoning sense of urbanism and civic awareness among a certain class/demographic of downtowners who were made to feel as though they had a say (or deserved one) in how the city was being shaped around them. (Edward Keenan documents the same thing through a less personal filter in his new book Some Great Idea: Good Neighbourhoods, Crazy Politics and the Invention of Toronto.) Did you have a sense as you wrote Here We Are Among the Living that you were writing a Toronto book? What role does the city play as a character in your story?

SB: I’m glad that my book brought something out for you about the changes that have been happening in Toronto. From the beginning I wanted to write about this city, which still, in the early years of the millennium, had a kind of stigma around it. It had never been and would never be as cool as Montreal. You couldn’t go hiking or skiing the way you could if you lived in Vancouver, and the weed was more expensive. The sense that Toronto was Hogtown with a sheen of Bay St. lawyers was why, in 2002 when Samba Elegua went marching alongside a spontaneous parade through the Financial District, it felt so incendiary. That youthful feeling of “nowness” that Heller describes—the acute, almost overwhelming awareness of the singular moment being experienced—was intensified by the newness of what we were doing.

As the decade progressed, we also developed a sense of being in a kind of precious time before gentrification entered full swing. I felt a tremendous poignancy about the east end. Ty’s loft on Eastern Ave. was across a waste lot from what is now the Distillery District. It was a ghost town when he moved in, one that we could traipse through and wonder what would become of the beautiful red bricks, the wood shutters and cobblestones. The Canary, on Cherry St., was still a functioning diner where we ate cheap breakfasts, discovering over those smokes-and-eggs that I was fetishising a certain aesthetic that was very indicative of where I came from and the kind of life I desired. So our twenties were largely about learning the city, and what kind of city we wanted—in part by assessing the gentrification rumbling toward Kensington and Leslieville. Knowing that the qualities for which we loved these places would threaten them later. There’s a petition going right now to keep Loblaws out of Kensington. I have nothing against Loblaws, but that would seriously alter the nature of the neighborhood. (On an amazingly happy note, I discovered last night that Casa Acoreana, the iconic coffee shop at the corner of Augusta and Baldwin, is not going to be gentrified out of business. The landlord was going to raise the rent, but the outcry from the neighborhood and in local newspapers was so impassioned that he rethought the increase, and the shop gets to stay. A rare and inspiring bit of beauty, that.)

Michael tried to convince me yesterday that the Starbucks on Logan has been there for ten years. Oh no it hasn’t, I said, and I’ll tell you why I know; when we used to walk to the Tango Palace [a coffee shop at Queen and Jones where we’d do our homework on the weekends] I’d say, there will be a Starbucks in this area within three years. And the year after you moved out [in 2006],

there was one.

I think the city in my story is a kind of muse. Certainly it made me want to write about it all the time. And it generates creativity and joy by bringing people together—Joe, for instance, comes to Toronto from England intending to go on to Vancouver, but changes his mind and stays because he likes it. A desire for the city to be a community inspires Streets Are For People!, the collective which creates Pedestrian Sundays in Kensington. And you’re right, that’s not just about dancing in the streets, or playing giant chess on the asphalt while eating empanadas; it’s about people being involved in the shape this city takes, and feeling like we have a responsibility and a right to advocate for things that will make life good here.

Street festivals like Taste of the Danforth, which has something like a million attendees now, engender a similar spirit, if perhaps in less direct ways. Even though there’s more of a consumerist bent to these bigger festivals, they still promote independent businesses and bring people together—and that’s good for the city as a whole. I love, too, that this discussion is coming to places outside the downtown core. I don’t know as much about this as I’d like to, but I’m really hopeful that street festivals, bike lanes and farmer’s markets aren’t just going to remain the purview of 416-ers.

Keenan’s book is definitely on my summer reading list. The changes in Toronto aren’t entirely great, but we’re getting a lot right and it’s nice that people are paying attention to what those things are, so we can keep ’em coming.

KC: Growing up in Toronto, did you have a sense of its literary landscape, which has been underlined by recent projects such as Amy Lavender Harris’ Imagining Toronto book and Project Bookmark installations? What Toronto books contributed to your own literary landscape?

KC: Growing up in Toronto, did you have a sense of its literary landscape, which has been underlined by recent projects such as Amy Lavender Harris’ Imagining Toronto book and Project Bookmark installations? What Toronto books contributed to your own literary landscape?

SB: Honestly, growing up in Toronto I felt like this city wasn’t on any literary map at all. In part, that’s probably because when I started seriously reading, in my late teens and early twenties, I was doing the young person thing of reading about everywhere else. So it was The Famished Road, by Ben Okri, and Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being. The Beats, of course. And trying to catch up on “the classics”—you know, The Great Gatsby, Dostoyevsky, Balzac…

So all through my early twenties, as I was thinking of writing this book, and scribbling notes for it, I was motivated in part by my love for a city that seemed undocumented. It was something we talked about, my friends, my mom and I—how no work of art had yet made Toronto “cool,” or even interesting. There was no romance about it at all. To some extent I still think that’s the case. Everyone I know was pretty darned excited when the movie Scott Pilgrim vs. The World came out, and we could recognize Bloor St., and there’s that scene where they’re CD shopping in Honest Ed’s.

It wasn’t until I was in the first year of my PhD, and TA’d for Modern Canadian Fiction, that I read a bunch of books set in Toronto: Hugh Garner’s Cabbagetown, which, despite now being unfashionable (its stodgy realism and blatant social agenda) I truly enjoyed. Austin Clarke’s excellent novel The Meeting Point was the first—and remains the only, come to think of it—depiction I’d read of Forest Hill. Barbara Gowdy’s labyrinthine Don Mills streets in Falling Angels were a revelation that Toronto’s suburbs had been made into art (which I hope to see a lot more of).

For me, best of all was Dionne Brand’s What We All Long For. That novel evokes the Toronto that I know and love: the youth of the four main characters capture the city’s restless, growing heart, its striving for beauty. The students loved that book, too. Our outstanding prof, Cheryl Cowdy, introduced us to the idea of psychogeography (now such a buzz word, thanks to Shawn Micallef’s 2011 book), and the concept just took off for students when we studied What We All Long For–I think because it was current, and the city so recognizable. The class got a lot of pleasure from looking at how characters were responding to their environments, and there are so many different Toronto environments depicted in Brand’s book that students were both learning about and identifying with; it made the fictional world very real to them, and I think made the city more real to them at the same time.

I’m excited that so much more art is being made in and about Toronto. I’d love to see more renderings of Toronto in the 1960s, or the 1980s, when I think a lot was changing. I’m working on a story set then; I’m hoping to include something about Operation Soap, the bathhouse raids on Richmond Street in 1981.

KC: So now I’m excited that you’re making more art in and about Toronto. Anything else exciting that you’re working on? And what are you reading right now?

SB: Well, there’s the short stories; the one that’s finished is a very long story called “The Optimists.” I’ve also got a lot of poems—many of which involve Toronto—that I’d like to turn into a book.

I’ve just started The Golden Bowl, by Henry James, who I love because he can make thinking the central action of a novel. I’m also reading a book called Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity by Richard Rorty, which I’m hoping is going to help me make a case for the social utility of liberal guilt and self

May 16, 2013

On book blogging and criticism

All my best opportunities usually come my way a week or two before or after I give birth, and you can’t say no. So at the moment, I am working on a review assignment I’m quite excited about, and I’m not remotely bothered that Baby will probably still be a little while in coming, because I have to get this article finished anyway. I am also pleased because from my post-partum stupour, I’ll see my name in print, and I imagine this will read as an encouraging sign from a world beyond (or behind) that I still exist, or at least that my writing does, somewhere. Anyway, none of this is really the point, which instead is that I’m thinking how much more time I spend on the books I’m reading for work than the books I read for fun, and what I’m missing. For example, the first time I read through this slim volume, I found it baffling and wondered how one was supposed to review a book one didn’t understand. And then I read it again, and again, and now all of a sudden I’ve got this ARC full of notes, crazy connections, ideas, and I’m working toward a spectacular synthesis of this short story collection which, you won’t believe it, won’t just be a summary of each of the stories contained within–who knew this was possible?

Now, fair enough, sometimes this isn’t possible. Some books are really as insubstantial as they appear at first reading. A lot of short story collections really are not very remarkable as wholes, or even in parts. I’ve been fortunate to have been assigned a book by a writer whose talent is extraordinary, and it’s this extraordinary work that has drawn me so deeply into this book I just skimmed across first time through. But it makes me wonder what would happen if I approached every book I read this closely, if I were this actively engaged, if all my unpaid reviews were as interesting and thought-out as this paid one is going to be. A few things: there is not time enough in the world, and the pay for my blog reviews is just the smallest bit, um, paltry for such dedication, and my blog is meant to be a kind of leisure for me, not labour. Also, for the past 39 weeks (and maybe even longer) I’ve been so so tired, but yes, I’ve be thinking about how much gets missed. What if the key to any book’s brilliance is just to read it enough times, to study it deeply enough? Of course, I’ve read enough terrible books to know the fault isn’t always mine, that there are terrible books indeed, that taste counts for something, that there are books and then there is *this book* I’m reading and writing in right now and which makes me consider the infinite possibilities of literature.

May 15, 2013

Basements and Attics, Closets and Cyberspace: Explorations in Canadian Women’s Archives by Morra & Schagerl

I am one of those readers who has bought into the romanticism of libraries and archives, Barbara Pym heroines and Maud Bailey in Possession. In 2001, I helped to unpack the Woolf Collection at the Pratt Library in its new sub-basement home, and it was one of the most remarkable things I’ve ever done. And even when it’s not romantic, archives are fascinating; one of my favourite books of recent years was Outside the Box by Maria Meindl about legacy of her grandmother’s archive, and unexpected questions: what do you do with a pile of papers covered on dust and cat hair, a colostomy bag stuck to the back? A question that probably wouldn’t faze most archival librarians, as Meindl discovers, and Susan McMaster too in her essay “Rat in the Box: Thoughts on Archiving My Stuff” from Basements and Attics, Closets and Cyberspace: Exploration in Canadian Women’s Archives (Linda M. Morra and Jessica Schagerl, eds). Her essay begins with a literary archivist asking for details, “Mouse turds or rat turds? A few mouse turds are nothing, they can be brushed off…”

I am one of those readers who has bought into the romanticism of libraries and archives, Barbara Pym heroines and Maud Bailey in Possession. In 2001, I helped to unpack the Woolf Collection at the Pratt Library in its new sub-basement home, and it was one of the most remarkable things I’ve ever done. And even when it’s not romantic, archives are fascinating; one of my favourite books of recent years was Outside the Box by Maria Meindl about legacy of her grandmother’s archive, and unexpected questions: what do you do with a pile of papers covered on dust and cat hair, a colostomy bag stuck to the back? A question that probably wouldn’t faze most archival librarians, as Meindl discovers, and Susan McMaster too in her essay “Rat in the Box: Thoughts on Archiving My Stuff” from Basements and Attics, Closets and Cyberspace: Exploration in Canadian Women’s Archives (Linda M. Morra and Jessica Schagerl, eds). Her essay begins with a literary archivist asking for details, “Mouse turds or rat turds? A few mouse turds are nothing, they can be brushed off…”

The connections between the essays in Basements and Attics, Closets and Cyberspace are broad and strange, as befitting a book of “explorations”. Why “Women’s Archives” in particular? Because it’s a whole different game that requires in some cases a redefinition of what archives are. One can’t go looking in ordinary places for women’s history, because for so long there was no such thing, and different ethical questions are raised about public and personal stories. But what does it mean for the archive to change the definition of archive? What is expanded and what is undermined? The book is a fascinating exploration indeed, and while it’s published by an academic press and makes a fair number of references to Derrida, much of it was accessible to the likes of me, and was a really enjoyable read.

In “Of Mini-Ships and Archives”, Daphne Marlatt writes of language itself as an archive, and asks, “Does writing… inherently contain the possibility of going public?” based on her experiences in archives using personal stories to provide context for larger issues. Cecily Devereau posits eBay as an archive, discussing its advantages and limitations over tradition archives in the quest for “Indian Maiden” lore. “Faster Than a Speeding Thought” by Karis Schearer and Jessica Schagerl was of particular interest to me, examining poet Sina Queyras’ blog Lemon Hound, the blog as archive and ethical implications of this (there is no permanence; who do comments belong to?; can there be such a thing as a paperless archive?) and poses interesting questions about blogs in general: “Although, on the one hand, controlling the means of publication can be a powerful tool for shaping the literary field, on the other hand, it does have its own implications for women’s labour.” In “Archiving the Repertoire of Feminist Cabaret in Canada”, T.L. Cowan attempts to use anecdotes to recreate an event whose ephemera has been entirely lost, and discusses what kind of archive emerges from this exercise. Penn Kemp writes about archives from the point of view of the archivee, as does Sally Clark who discusses her own discomfort with archiving and the question it requires of her: “What are you worth?”

In “Keeping the Archive Door Open: Writing About Florence Carlyle”, Susan Butlin presents some of the unique challenges of researching Canadian women’s history, and the role of her own prejudices in the process (as she discovers the more commercial ventures of the artist Carlyle). Ruth Panofsky and Michael Moir’s “Halted by the Archive: The Impact of Excessive Archival Restrictions on Scholars” tells of Panofsky’s experiences with Adele Wiseman’s archives when Wiseman’s daughter suddenly made her mother’s archives inaccessible to scholars. The limits of traditional archives are further explored in Karina Vernon’s “Invisibility Exhibit: The Limits of Library and Archives Canada’s “Multicultural Mandate”. Katja Thieme uses letters to the Woman’s Page of Grain Grower’s Guide to show how the page function as an archive of rhetoric which underlines our understanding of the Canadian suffrage movement. Vanessa Brown and Benjamin Lefebvre discuss the archive of LM Montgomery and its role in their own work, as well as its inherent gaps and mysteries. Kathleen Venema uses an archive of her own–a collection of letters exchanged between her and her mother decades ago–to create a new archive and explore the limits of her mother’s memory as she becomes more and more afflicted with Alzheimer’s. In “Locking Up Letters”, Julia Creet questions what is she to do with her mother’s letters about her experiences during the Holocaust when the letters are of vast historical import but also recount experiences that her mother spent the rest of her life trying to flee from and hide.

Basements and Attics, Closets and Cyberspace is not a tidy book, but what exploration in an archive (or any one worth exploring) ever would be? Rather than putting away things in boxes, this book throws the boxes open wide, inviting more questions than answers, and demanding a broader point of view.

May 14, 2013

Baby Blankets and Mini Monsters

We sure hope our baby doesn’t end up with jaundice because this blanket/cap combo really isn’t going to flatter if that happens. Blanket and cap are yellow as per Big Sister’s instructions, as yellow is the colour she most reveres, and basically the baby is welcome to be born at any time because Harriet has had her birthday party and the blanket is done. This is the Big Bad Baby Blanket, which I’ve knit many times before, and I made a little hat with the leftover wool. The blanket is pretty lovely with just enough errors that you’d know it was handmade if you went looking for problems, but none that stand out too much. Strange that it won’t be too long before we meet the wee person these knitted things are meant for. At this point, it’s still quite unbelievable to suppose that it’s really going to happen. It feels like these are ordinary days–who’d go and throw a newborn into the midst of that?

We sure hope our baby doesn’t end up with jaundice because this blanket/cap combo really isn’t going to flatter if that happens. Blanket and cap are yellow as per Big Sister’s instructions, as yellow is the colour she most reveres, and basically the baby is welcome to be born at any time because Harriet has had her birthday party and the blanket is done. This is the Big Bad Baby Blanket, which I’ve knit many times before, and I made a little hat with the leftover wool. The blanket is pretty lovely with just enough errors that you’d know it was handmade if you went looking for problems, but none that stand out too much. Strange that it won’t be too long before we meet the wee person these knitted things are meant for. At this point, it’s still quite unbelievable to suppose that it’s really going to happen. It feels like these are ordinary days–who’d go and throw a newborn into the midst of that?

The little monster is Harriet’s gift for the baby. For months, she’s been determined that she was saving the money in her piggy bank to buy a present for the baby. A few weeks ago, we gathered funds (and were grateful to whomever had once given her a ten dollar bill) and went to the Intergalactic Travel Authority to purchase Maggie the Monster, Harriet’s chosen companion for her own Colin, and our baby’s future crib-mate. For all my deriding of consumption (book buying aside, naturally), it was quite adorable to watch Harriet make her first purchase in a shop. They told her the total and then she handed them a nickel and asked if it was enough. I had to help her with the rest, but was quite proud of her and the spirit of generosity behind the project. I really do think that Harriet is going to take to the Big Sister life with aplomb, and that our baby who is not yet even born is already incredibly lucky.

May 12, 2013

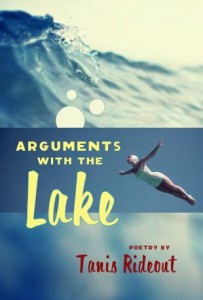

Arguments with the Lake by Tanis Rideout

…Let’s step now to these gathering places./Name them–our birthright, strung like beads/ on northern shores. Let’s lay claim to the stories/ on this lake, the aquatic murmur of what’s past/ what’s to come.

…Let’s step now to these gathering places./Name them–our birthright, strung like beads/ on northern shores. Let’s lay claim to the stories/ on this lake, the aquatic murmur of what’s past/ what’s to come.

Oh, it’s become a bit of a pattern, hasn’t it, me falling in love with poetry that give voice to obscure figures from the past. This time it’s Tanis Rideout’s poetry collection Arguments With the Lake, which imagines a friendship/rivalry between Marilyn Bell and Shirley Campbell, two women who as girls were determined to swim across Lake Ontario just two years apart. Bell made it and became a legend, while Campbell disappeared into obscurity after two failures to complete her swim. Rideout imagines the connections which bind these two girls, the force which drew them both to the lake’s edge and made them attempt to be a part of history. As the book’s exquisite cover suggests, there is 1950s’ bathing-beauty glamour going on here with a particular Toronto bent–Sunnyside Beach and the Palais Royale. The poems also examine the darker forces of friendship, of womanhood, of what inevitably follows girldom, stardom. The lake itself is Rideout’s main character though throughout the book, speaking back to each of the girls’ arguments, enduring but ever-changing. From “The Fear of Silence”: “The shoreline changes more than its citizens. The city/ has leeched into the lake. Front Street really was the Front./ Fisherman docked at the market’s doors. It is as though/ we want to live in that water–press into it, fill it up,/ like empty hours filled now with digital detritus”. I loved this book.