July 15, 2013

Bobcat by Rebecca Lee

I had only read the first story in Rebecca Lee’s short story collection Bobcat before I’d ordered a copy of her novel from the bookstore. Why, I wondered already, had this collection not been more hyped? Not until it was awarded the Danuta Gleed Award a few weeks back did it really come to my attention. But one story was all it took for me to realize that Lee is a writer approaching mastery of her craft. As significant, I think, as the fact that she received an MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop is that she received it 21 years ago. That Lee has had time to grow and develop as a writer so she’s no ingenue, but instead her writing reveals a maturity that is most admirable. Her grasp of these stories was so firm, and her voice so strong that I knew I’d be wanting more of it. I look forward to reading her novel The City is a Rising Tide very soon.

Rebecca Lee’s short stories share the same approach as Sarah Selecky’s, the same intimate first-person narration, close attention to detail that sets these characters as very much of this world (lines like “Lizbet basically knew how to live a happy life, and this was revealed in her trifle–she put in what she loved and left out what she didn’t”)–as well as dinner-party settings and fork on the cover. But on the other side, Lee’s marvelous telescoping endings and ultimate broadness of perspective remind me of the stories in Jhumpa Lahiri’s The Interpreter of Maladies. (I think “Bobcat” may join Lahiri’s “The Fifth and Final Continent” as one of my favourite short stories ever.) These stories were written over two decades and accordingly the collection lacks a certain cohesion, except for (and this is significant) the solidity of Lee’s voice.

“One of the things Strandbakken had been struggling to teach us was that a building ought to express two things simultaneously. The first was permanence, that is, security and well-being, a sense that the building will endure through all sorts of weather and calamity. But it also ought to express an understanding of its mortality, that is, a sense that it is an individual and, as such, vulnerable to its own passing away from this earth. Buildings that don’t manage this second quality cannot properly be called architecture, he insisted. Even the simplest buildings, he said, ought to be productions of the imagination that attempt to describe and define life on earth, which of course is an overwhelming mix of stability and desire, fulfillment and longing, time and eternity.” –from “Fialta”

Lacking a certain cohesion (which in a collection this good is less a criticism than a statement of fact), yes, but there are more than a few points in common. Three of these stories take place in academic settings. These are stories written with an awareness of history and not just a general contemporariness. They are filled with allusions and references to actual places, people, and things. Though “Bobcat” is like this least of all, the first story, about a dinner party and so tightly contained within four walls that the effect is claustrophobic until the story’s incredible ending in which the whole thing explodes. A hostess is acutely aware of the inner lives and workings of her dinner guests, so much so that she’s blind to her own destiny. The people in this story are so vivid and real, and the ending was both incredible and heartbreaking. “The Banks of the Vistula” is a 1980s’ Cold War story (“But this was 1987, the beginning of perestroika, of glasnost and views of Russia were changing. Television showed a country of rain and difficulty and great humility, and Gorbachev was always bowing to sign something or other, his head bearing a mysterious stain shaped like a continent one could almost but not quite identify” [and how I love that “almost but not quite…]) about a university student who plagiarizes a linguistics paper from 1950s’ Soviet propaganda.

“Slatland” is a peculiar story about a strange psychologist and his impact on a young patient who returns to him years later looking for him to translate letters her Romanian fiance is writing to a woman whom she suspects is her fiance’s wife. In “Min”, another Midwestern university student travels to still-British Hong Kong and is enlisted with the job of selecting him a wife, as her friend’s diplomat father is being faced with the morally ambiguous task of deporting Vietnamese refugees. In “World Party”, a female professor during the 1970s’ uses her relationship with her (perhaps autistic?) son to decide the future of a male colleague who has been accused of a sexually inappropriate relationship with a student. And the final story is “Fialta”, in which architecture becomes analogous to story-writing and a group of students enrolled in an elite mentorship program fall in and out of love with one another, learn, come of age and of self, and are each uniquely bound to their teacher for better or worse.

July 15, 2013

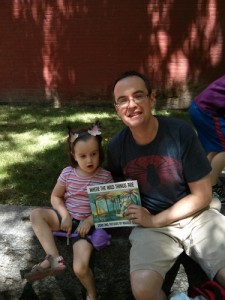

The Wild Rumpus

I learned about Story Mobs on Friday, and knew immediately what we’d be up to the next day. What an adventure: “where great kids’ books meet flash mobs with a dash of Mardi Gras thrown in.” Our family met up with many others in a small park behind Nathan Phillips Square on Saturday afternoon with our maracas on hand, along with wolf ears and a copy of Where the Wild Things Are. Now, we have a newborn in the family and we’re quite crap at organization (wolf ears created 10 minutes before we left the house), so our preparations paled in comparison to those of others who were exquisitely attired and were carrying amazing props. We took part in a rehearsal of the story’s reading, and then made a parade with all the other wild things to the pool in front of City Hall where we drew attention with strange costumes, samba drums, and the general oddness of our presence. The story began, featured readers projecting their voices across the square and the rest of us participating with responses. My favourite part is when we got to shout: “Oh, please don’t go. We’ll eat you up! We love you so.” Though the wild rumpus itself was nothing to be scoffed at as we danced like wild things around Nathan Phillips Square with a bunch of similarly-minded strangers in the sunshine. (The Ai Weiwei sculptures in the pool added nicely to the effect, I think.) And then Max sailed back in and out of weeks to his very own room where his supper was waiting. It was still hot, which deserved a cheer, we thought, and then we scattered, and the event was over as though it had never begun, except for in the minds of those of us who were there.

I learned about Story Mobs on Friday, and knew immediately what we’d be up to the next day. What an adventure: “where great kids’ books meet flash mobs with a dash of Mardi Gras thrown in.” Our family met up with many others in a small park behind Nathan Phillips Square on Saturday afternoon with our maracas on hand, along with wolf ears and a copy of Where the Wild Things Are. Now, we have a newborn in the family and we’re quite crap at organization (wolf ears created 10 minutes before we left the house), so our preparations paled in comparison to those of others who were exquisitely attired and were carrying amazing props. We took part in a rehearsal of the story’s reading, and then made a parade with all the other wild things to the pool in front of City Hall where we drew attention with strange costumes, samba drums, and the general oddness of our presence. The story began, featured readers projecting their voices across the square and the rest of us participating with responses. My favourite part is when we got to shout: “Oh, please don’t go. We’ll eat you up! We love you so.” Though the wild rumpus itself was nothing to be scoffed at as we danced like wild things around Nathan Phillips Square with a bunch of similarly-minded strangers in the sunshine. (The Ai Weiwei sculptures in the pool added nicely to the effect, I think.) And then Max sailed back in and out of weeks to his very own room where his supper was waiting. It was still hot, which deserved a cheer, we thought, and then we scattered, and the event was over as though it had never begun, except for in the minds of those of us who were there.

Another Story Mob is scheduled for two weeks from now with Jillian Jiggs being performed. Thanks to Bunch Family for bringing this fabulous event to my attention!

Another Story Mob is scheduled for two weeks from now with Jillian Jiggs being performed. Thanks to Bunch Family for bringing this fabulous event to my attention!

July 7, 2013

The Silent Wife by ASA Harrison

For me, last weekend belonged to The Silent Wife by A.S.A. Harrison, a perfect summer book if compulsive page-turning in the sunshine happens to be your thing. It’s a book that’s been compared favourably to Gone Girl, though it’s a very different literary creature. It’s not a whodunit, but instead a “Why’d she do it?” It being murder, of course. We learn at the novel’s outset that Jodi will kill Todd, her husband of 20 years, and the rest of the novel illuminates what would bring a seemingly rational woman to such a point.

For me, last weekend belonged to The Silent Wife by A.S.A. Harrison, a perfect summer book if compulsive page-turning in the sunshine happens to be your thing. It’s a book that’s been compared favourably to Gone Girl, though it’s a very different literary creature. It’s not a whodunit, but instead a “Why’d she do it?” It being murder, of course. We learn at the novel’s outset that Jodi will kill Todd, her husband of 20 years, and the rest of the novel illuminates what would bring a seemingly rational woman to such a point.

“Seemingly” is the key word though. Jodi Brett is rational to the point of near-madness, a therapist who prides herself on psychological acuity. It seems that she is as blind to her own self, however, as she imagines she is to her husband indiscretions. Todd is a cheater, and he’s always been, but the stakes are different now. Natasha, the daughter of Todd’s oldest friend, is pregnant, and she informs Jodi that they’re going to be married. Married. Which Jodi and Todd have in fact never been, Jodi adamant that she will not relive the life of her mother, eternally put-upon by a philandering husband. No, she’s always refused to be married, even when Todd asked her, just as she refused to see that her life has assumed the same shape as her mother’s anyway.

The story is told in alternating chapters from each partner’s perspective. Todd is a convincing portrayal of a guy who just can’t help himself, though that Jodi has tolerated his cheating for two decades suggests that she’s less a victim than an enabler. It is hard to have sympathy for either of them, and what compels the reader instead of any sympathy is curiosity as this disastrous relationship heads toward its inevitable end. Curiosity too to unravel the workings of Jodi’s mind, and while Harrison provides an impetus for her behaviour that detracts from the story, it’s still fascinating to see insanity comes in all matter of forms. That is terms of awfulness, Jodi and Todd are in fact a perfect match.

Harrison manages to craft suspense in a story whose outcome is sure from the beginning, though not entirely sure. The conclusion of The Silent Wife is still surprising, ambiguous and clever, the perfect ending to a really good book.

July 5, 2013

One Whole Month of Iris

When I wrote “Love is a Let-Down”, the point was not to say that new motherhood is necessarily a terrible experience, but instead to underline how different it is for everyone. That for many of us, the experience didn’t align with the greeting card slogans. We’re not over-the-moon but instead completely overwhelmed by a world that has been shattered into pieces and put back together in a still-broken state. And now I worry that in my current state of mind I’m letting down the team a little bit, undermining the message of those who’ve dared to speak honestly about what it is to become a mother. But then again, I’m really not undermining it at all, but instead underlining my main point which is that every woman comes to motherhood in her own way. Because this time, with my second baby, the experience has been everything it wasn’t first time around. I’ve become a walking greeting-card slogan myself—“Everything is going really well!” If I wasn’t living it, I’d be convinced I was lying.

When I wrote “Love is a Let-Down”, the point was not to say that new motherhood is necessarily a terrible experience, but instead to underline how different it is for everyone. That for many of us, the experience didn’t align with the greeting card slogans. We’re not over-the-moon but instead completely overwhelmed by a world that has been shattered into pieces and put back together in a still-broken state. And now I worry that in my current state of mind I’m letting down the team a little bit, undermining the message of those who’ve dared to speak honestly about what it is to become a mother. But then again, I’m really not undermining it at all, but instead underlining my main point which is that every woman comes to motherhood in her own way. Because this time, with my second baby, the experience has been everything it wasn’t first time around. I’ve become a walking greeting-card slogan myself—“Everything is going really well!” If I wasn’t living it, I’d be convinced I was lying.

Of course, anyone who’s ever had a second baby will tell you that this is what happens. They told me, actually, but I didn’t believe them, or else I certainly didn’t believe that it could be possible for someone like me who was so notoriously terrible at new motherhood. That this time you know what you’re doing, you learn to ride the chaos instead of thinking you’re doing it wrong, that it all goes by faster and you really do try to enjoy every minute.

Of course, anyone who’s ever had a second baby will tell you that this is what happens. They told me, actually, but I didn’t believe them, or else I certainly didn’t believe that it could be possible for someone like me who was so notoriously terrible at new motherhood. That this time you know what you’re doing, you learn to ride the chaos instead of thinking you’re doing it wrong, that it all goes by faster and you really do try to enjoy every minute.

It is a different experience altogether. That first baby requires “becoming a mother”, which comes less naturally to some of us than others. I’m reminded of the trauma undergone by astronauts when they re-enter the earth’s atmosphere–my experience was the emotional equivalent of that. But this time, I’m a mother already and there is no becoming necessary. There is none of the shattering, the loss of self that was so terrifying to experience. I am fundamentally unchanged by the birth of Iris, except that our family is a different shape and the world is just a little bit bigger.

It is a different experience altogether. That first baby requires “becoming a mother”, which comes less naturally to some of us than others. I’m reminded of the trauma undergone by astronauts when they re-enter the earth’s atmosphere–my experience was the emotional equivalent of that. But this time, I’m a mother already and there is no becoming necessary. There is none of the shattering, the loss of self that was so terrifying to experience. I am fundamentally unchanged by the birth of Iris, except that our family is a different shape and the world is just a little bit bigger.

Motherhood is a storm, is the quote by Laurie Colwin that I seized on, the metaphor that so clearly articulated what I was going through. But it’s not been stormy this time. Instead, I’d say it’s been like a summer’s day, albeit one sometimes experienced from my bed but with the patio door wide open and the sun pouring in. The baby is screaming, her face so red that I’m reminded of a cartoon character with smoke coming out its ears, but this is funny instead of traumatic. I’ve got living proof asleep in a bedroom downstairs that this wretched, squalling foetal creature is in fact going to grow into an actual human being. And so that’s how one becomes a greeting-card slogan, all consumed by how fast the days are flying by and by the smell of the baby’s head.

Motherhood is a storm, is the quote by Laurie Colwin that I seized on, the metaphor that so clearly articulated what I was going through. But it’s not been stormy this time. Instead, I’d say it’s been like a summer’s day, albeit one sometimes experienced from my bed but with the patio door wide open and the sun pouring in. The baby is screaming, her face so red that I’m reminded of a cartoon character with smoke coming out its ears, but this is funny instead of traumatic. I’ve got living proof asleep in a bedroom downstairs that this wretched, squalling foetal creature is in fact going to grow into an actual human being. And so that’s how one becomes a greeting-card slogan, all consumed by how fast the days are flying by and by the smell of the baby’s head.

It has been a good month. My husband has been a huge part of this. Whereas the early days of Harriet challenged our relationship like nothing else, we have been so kind to one another since Iris arrived. That he is able to be on parental leave means that the hardships weigh more equally on both of our shoulders. He has taken extraordinarily good care of me during my recovery. And as I’ve recovered, we have had fun together, with Harriet too when she wasn’t yelling at us. (We now understand why people enroll their children in camp all summer long.) And now that I am nearly recovered, a brilliant summer lies before us. It’s all more graspable than I dared to imagine it was.

We went out for lunch today (of course) to celebrate a month of Iris, and to toast to the three of us for so successfully weathering the last few weeks. And now Harriet’s asleep and Iris is squawking downstairs, so I must go down to feed her, but while I do, we’ll be watching The Hour, which is so so good, and this nightly television thing is the most excellent ritual. Previously, we’d both worked in the evenings and TV was a treat saved for Friday nights (with wine) but now every night is Friday night, and how can you fault a life like that? It might as well be July. And it actually is.

Iris is gorgeous when she sleeps, slightly weird looking awake, and entirely beloved by every member of her family. Her most remarkable attribute was that she was born with a tooth. We are curious about who she’s going to grow to be, but we love her already. She looks a bit like her sister, but more like her self, and a little bit like me who also had ginger eyebrows as a baby. She is usually asleep or calm when people meet her, undermining her reputation as a miserable person. She likes to sleep in my bed in my armpit, which is a bit counter to what the safe-sleep advocates say, but I guess we like to sleep dangerous. I think we’re safe though, because she doesn’t really sleep that much. She took a soother once, and I was overjoyed, but hasn’t done it after. Since her birth a month ago, she’s gained two whole pounds, which is amazing. She gazes at Harriet like she looks at no one else, though I’ve gazed at Harriet myself so I can’t say I blame her. Her mouth is beautiful. She also likes to fall asleep on people’s chests, and she’s not yet discriminating about whose. Her belly button is shaped like an @ sign. She screams a lot and hates most things, but still manages to be adorable. And there is not really much else one can say when describing someone her age, but we’re so excited to get to know more and more about her.

July 3, 2013

Redfish Bluefish

Over at Bunch, I wrote about our new favourite cafe Redfish Bluefish. Read my piece here.

July 2, 2013

Incredible Journeys

We were thrilled to visit the Incredible Journeys exhibit at the Lillian H. Smith Library’s Osborne Collection of Early Children’s Books. We all loved the pop-up books featuring trains, boats and planes, and the displays featuring storybook characters travelling in balloons, airships, by train, bicycle, public transit, and also “journeys of the mind”. It was exciting to see so many books we recognized–Curious George, Canadian Railway Trilogy, and more*, and also to see so many beautiful old illustrated books for the first time. But the particular highlight was an actual map of the Island of Sodor and several first-edition books from The Railway Series (which was a precursor to Thomas the Tank Engine).

We were thrilled to visit the Incredible Journeys exhibit at the Lillian H. Smith Library’s Osborne Collection of Early Children’s Books. We all loved the pop-up books featuring trains, boats and planes, and the displays featuring storybook characters travelling in balloons, airships, by train, bicycle, public transit, and also “journeys of the mind”. It was exciting to see so many books we recognized–Curious George, Canadian Railway Trilogy, and more*, and also to see so many beautiful old illustrated books for the first time. But the particular highlight was an actual map of the Island of Sodor and several first-edition books from The Railway Series (which was a precursor to Thomas the Tank Engine).

The exhibit is on until September.

*I would delineate exactly which ones, except that I haven’t slept more than 2.5 hrs in a row in a month and therefore my short-term memory has been obliterated. I remember being very impressed though. Really!

July 1, 2013

The Flame Throwers by Rachel Kushner

“A funny thing about woman and machines: the combination made men curious.”

I do wonder if one day there will be a literary genre distinguished by its treatment of women whose broken dreams are symbolized by their dissatisfaction with their kitchen renovations. I noticed this first in Arlington Park by Rachel Cusk, whose middle-class preoccupations were redeemed by Cusk’s Woolfian narrative, and then recently in Krista Bridge’s The Eliot Girls which was more Picoultian than Woolfian and left me frustrated with narrative in general. And so I turned to Rachel Kushner’s The Flame Throwers next, because it promised to be not Picoultian in the slightest and featured a female protagonist who never went into the kitchen at all.

Though to call her a “protagonist” is not entirely accurate, because Kushner’s narrator is more of an observer, and a cypher than one who the story happens to. We get a sense of her internal monologue, but not of her self–we don’t even know her name. (I am careful not to refer to her as “Reno” [um, for the city, not the abbreviation for “renovation”] though she is referred to as such in the book’s copy. But in an interview, Kushner remarks, “Twice, she’s referred to as Reno, and so reviewers have latched onto this.” And I don’t want Kushner to think that I am a latcher. Never.) This is a novel about motorcycles, motor racing, rubber manufacturing, Fascism and terrorism, which is the kind of novel that generally wouldn’t appeal to me, except that it’s also the book that everybody is talking about and for once I wanted to get in on that action. Plus, it’s a novel about all of these things from the point of view of a female character, and I was curious about that. And so I picked up The Flame Throwers, and perhaps I’ve got a thing for speed and crashes after all because I was hooked by page 21 with the story of a legendary American racer whose parachute failed and had to stop from 522 miles per hour on the salt flats of Utah.

Of course, to call Kushner’s character an “observer” is disingenuous, because while the novel doesn’t happen to her, her voice and perspective are certainly key to its construction. She has more agency than we can really understand. The story begins with Kushner’s character on the salt flats in 1977, riding her Valera motorcycle (which had come from her boyfriend back in New York, Sandro Valera, the estranged heir to the Italian motorcycle/tire manufacturing fortune). Her aim is to race her bike, and also to photograph other races. She is an artist, we learn, who has moved from Reno to New York where she met Sandro. Her racing plans are curtailed by an accident, however, and she, previously the lone wolf, ends up with the Valera racing team by virtue of her motorcycle’s make. She ends up setting a world record for female drivers in the Valera car, the Spirit of Italy, and a scheme is concocted wherein she will travel to Italy on the coattails of her racing fame.

And then the narrative takes us to New York nearly two years before, the girl from Reno arriving in the city to make herself (though we learn a few peculiar details to suggest she’s not entirely formless–she’d been a success as a ski racer years before, and once acted in a McDonalds commercial. She grew up in a household with two motorbike-mad cousins, and an uncle who watched TV in the nude. And even the most mundane detail begins to seem conspicuous because there are so few of them). She tells us, “I thought this was how artists moved to New York, alone, that the city was a mecca of individual points, longings, all merging into one great light-pulsing mesh and you simply found your pulse, your place.” But she fails to, remaining estranged from the city itself, from its art scene. She is young and naive, and through a cast of eccentric characters (“I once went to a house in the Hollywood Hills that was a glass dome on a pole, its elevator shaft. Belonged to a pervert bachelor and he had peepholes everywhere. He was watching me in the toilet. Some guy drugged me without asking first. Angel dust. I was on roller skates which presented a whole extra challenge.”) she meets artist Ronnie Fontaine, and falls in love with his best friend, Sandro Valera. She makes her place on the scene as Sandro’s girl, but overrides him when he resists the idea of her trip to Italy.

In chapters involving Sandro’s father, we learn the sordid details of how he made his fortune and these suggest just why Sandro is so uncomfortable with returning to Italy and why he is determined to remain distanced from his family heritage. When the trip finally happens, it is the disaster he predicted, as Sandro’s mother shows disdain for his American girl, and the whole family is troubled by political uprisings by their factory workers, which were part of a movement sweeping the country in 1977. And finally, our character is faced with the truth about her boyfriend’s intentions toward her, and in an instant she makes a decision that embroils her in Italy’s underground radical social movement.

Kushner’s prose thrums with a Didion-esque rhythm, and her narrative concerns read like a combination of “Good-Bye to All That” and “Slouching Towards Bethlehem”. Her sense of time and place is stunningly evoked, and while details waver in a few places, the overall impression is of remarkable realization. There is a reason everyone is talking about this book, and that’s because it’s a great American novel in the grand tradition but as rendered by a female hand, but then this novel with all its masculine concerns is a treatment of the feminine as well. What is the place of Kushner’s female character in this kind of story? Is she the I or just the eye? Does anybody hear her voice beyond us, the reader? We hear her, but what are the impressions of those who can see her? In a way, she is as invisible as the “China Girl” appearing among the first frames of movie film, ever present but anonymous and glimpsed by almost no one. Is this the extent of possibility for the woman artist? (“You’re not supposed to evoke real life. Just the hermetic world of a smiling woman holding a colour chart.”)

So much of this book’s impact comes from its evasive approach, which is summed up in its final sentence: “Leave, with no answer. Move on to the next question.” And that’s why so many people are talking about this book–because it’s a difficult one from which to draw tidy conclusions.

June 27, 2013

My review of The Dark by Lemony Snickett and Jon Klassen

Lucky me. I got to review The Dark, a new picture book by Lemony Snickett and Jon Klassen. It was such a pleasure to read and review.

Lucky me. I got to review The Dark, a new picture book by Lemony Snickett and Jon Klassen. It was such a pleasure to read and review.

““Laszlo was afraid of the dark,” the book begins. The accompanying illustration shows Laszlo playing with his trucks in a shrinking ray of light, the sun outside the window starting to set. When the sun goes down, shadows fall throughout the house, and Laszlo fends them off with his ever-present flashlight and night light. But when the bulb in his night light burns out, Laszlo is forced to face his deepest fears.”

Read the rest here. And get this book!