August 27, 2014

Big Shoes

The last few days have been huge for Iris, who is just a week shy of being 15 months old. She spent about four days straight sleeping until at least 4am (and one day until 6:00, which was massive, but then we had to contend with being up at 6:00. At least when she wakes up at 4:00, I can bring her to bed until the alarm goes off…) and, most dramatically, after 8 months of only ever wanting to read Little You by Richard Van Camp (and hey, if you’re going to read 1 book 948 times this year, let this one be the one…), she’s become obsessed with I Want My Hat Back by Jon Klassen—she likes his illustrations of the bear. Lately. she’s also really into Jack and the Box by Art Speigelman, which she thinks is terribly funny, and she’s right. So Iris is proving herself to be quite discerning in her literary tastes, never mind her affinity for any bookish translation of The Wheels on the Bus.

The last few days have been huge for Iris, who is just a week shy of being 15 months old. She spent about four days straight sleeping until at least 4am (and one day until 6:00, which was massive, but then we had to contend with being up at 6:00. At least when she wakes up at 4:00, I can bring her to bed until the alarm goes off…) and, most dramatically, after 8 months of only ever wanting to read Little You by Richard Van Camp (and hey, if you’re going to read 1 book 948 times this year, let this one be the one…), she’s become obsessed with I Want My Hat Back by Jon Klassen—she likes his illustrations of the bear. Lately. she’s also really into Jack and the Box by Art Speigelman, which she thinks is terribly funny, and she’s right. So Iris is proving herself to be quite discerning in her literary tastes, never mind her affinity for any bookish translation of The Wheels on the Bus.

It is exciting to see her own tastes developing. Though we’ve known for a long time that she loves the CD Throw a Penny In the Wishing Well by Jennifer Gasoi, because she started dancing the first time she heard it, which was also the first time we learned that she knew how to dance, but now she listens to the song, “Happy”, and sings along, and then walks around the house saying, “Hap-pee. Hap-pee.” One of the few words she knows—though she added another tonight at the Farmer’s Market when she exclaimed, “Cheese,” in pursuit of a sample. She got one.

She doesn’t know that she’s a baby. She thinks that she can read, and opens books, thumbing through them and muttering as the flips through the pages, or maybe she thinks that we think she can read, and we’ll let her think that. Her dignity is very important. She also insists on china plates and cutlery for all her meals, and she wields a fork like a champion. It’s a bit eerie to be in her company, because she seems to be watching us too carefully—whenever I fiddle with my hair, she does the same with the fluff on her skull. She watched her dad dry his hair the other morning, and then grabbed a hand towel and dried hers too. She has new shoes (see photo), and insists on wearing them everywhere, and fetching them before we go somewhere is her favourite part of any outing, I think. When we arrive back home, she sits down to take them off, and nobody ever taught her to do that. In fact, nobody has ever taught her anything, but she keeps knowing new things all the time, blowing her own mind, and our minds, every single day.

August 25, 2014

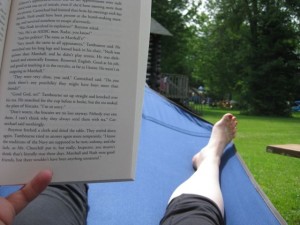

The Long Way Home by Louise Penny

It was almost exactly a year ago that Louise Penny’s How the Light Gets In came out, a book I was so excited about that I purchased it the day of its release. And I loved it—it was one of my favourite books of the year. All the usual suspense and emotion and I’ve learned to expect from a Louise Penny novel, and then she goes and pulls this literary sleight of hand that was so exciting and perfect. The novel concluded the plot of police corruption that had been building since Penny’s Inspector Gamache series began, and it was with some sadness that I concluded that the series was probably finished, retired along with the Chief Inspector. What a way to go though–it was an absolutely terrific novel.

It was almost exactly a year ago that Louise Penny’s How the Light Gets In came out, a book I was so excited about that I purchased it the day of its release. And I loved it—it was one of my favourite books of the year. All the usual suspense and emotion and I’ve learned to expect from a Louise Penny novel, and then she goes and pulls this literary sleight of hand that was so exciting and perfect. The novel concluded the plot of police corruption that had been building since Penny’s Inspector Gamache series began, and it was with some sadness that I concluded that the series was probably finished, retired along with the Chief Inspector. What a way to go though–it was an absolutely terrific novel.

So I was surprised and pleased to discover earlier this year that there was more Gamache on the horizon. The Long Way Home finds Gamache retired to Three Pines, looking for a break from homicide (though Three Pines really is the last place I’d ever go to find such a thing). He’s uneasy, a bit restless, watchful of his protege (who is also now his son-in-law), concerned that Jean-Guy might slip back into addiction. Concerned for his own mental health too, as is his loving wife, Reine-Marie, who knows that Armand has not yet found the peace he so desperately requires. So she’s unsurprised but also worried when their neighbour and friend, Clara Morrows, comes to him with yet another mystery to solve.

Clara’s husband Peter is missing. They’d agreed upon a year’s separation, after her surprise success in the art world caused friction in the dynamic of their marriage, and on the set date, he didn’t materialize. She hasn’t heard from him at all, which wasn’t like him, and she is fearing for his safety. Having lived in Three Pines long enough, Clara is well aware that no mystery brings with it a simple solution, and that murder lies at the heart of most things, so she’s concerned. As is Armand, and Reine-Marie, and all their other friends, who band together to find Peter. They trace his travels across Europe, to a strange place in Scotland called the Garden of Cosmic Speculation, to Toronto, Quebec City, and then into the wilds of the province. Going on instinct, vague clues, discerning locations from Peter’s paintings, and interviews with people who’d seen him during the past year, they’re able to piece together Peter’s own story, which seems more and more suspicious the closer they get to finding him. Their sense that Peter is in danger turns out to be well-based, and it becomes clear that time is of the essence.

It was always going to be difficult to follow up Where the Light Gets In, which tied up so many loose ends and came together so majestically. The Long Way Home seems to be much less organic in its construction, requiring suspension of disbelief from the reader for the plot to make sense, and the plot itself cobbled together of pieces rather than woven into a whole. Part of the problem is that for much of the book, the mystery that needs solving is less than pressing—the whodunnit is more like, “Who done what?” There’s not even a murder until quite late in the book, which for Three Pines is all-time record, and quite unfathomable. And that the residents of Three Pines would have the resources (time and money) to devote to finding their friend, whose imperilled state is not really apparent, seems unlikely. It’s the kind of book that when you start to read to closely all sort of falls apart.

But. If you’re a fan of the Gamache novels, there’s no way you’re going to miss this one. The place seems so realized, and it’s people familiar—how could you not want to know what happens next? And while the pieces don’t come together terribly well, the pieces themselves are fascinating, revealing remarkable corners of its author’s mind, her preoccupations. If you’re new to the series, then definitely go back to the beginning, and don’t read this one before How the Light Gets In. Which was always going to be a book so hard to follow up.

August 24, 2014

Discover The Art of Blogging at UofT

It has been ages since I taught The Art of Blogging at the University of Toronto’s School of Continuing Studies, but I’m so pleased that the course is being offered this fall. Online is such a fast world that blogging has changed a lot since I last taught the course, and so has some of my thinking about blogging. Moreover, teaching small blogging workshops (like at the Wild Writers Festival in Waterloo!) has taught me a lot about the best way to present this kind of material and get students engaged. And so all of this will really culminate in a fresh and exciting class, I think. I’ve revised the course outline significantly (you can view it here!). We’re going to focus on learning to love the unpolished nature of the blogging, and embrace its work-in-progress-ness, and there will be lots of writing exercises to get students used to blogging efficiently. We’re going to explore using blogging in a way that fits neatly into your life, and even how blogging can make you live your life a bit better. I look forward to good discussion, sharing of experiences, lots of inspiring blog reading, and delving into the history of this fascinating medium as we all move forward as part of its future.

It has been ages since I taught The Art of Blogging at the University of Toronto’s School of Continuing Studies, but I’m so pleased that the course is being offered this fall. Online is such a fast world that blogging has changed a lot since I last taught the course, and so has some of my thinking about blogging. Moreover, teaching small blogging workshops (like at the Wild Writers Festival in Waterloo!) has taught me a lot about the best way to present this kind of material and get students engaged. And so all of this will really culminate in a fresh and exciting class, I think. I’ve revised the course outline significantly (you can view it here!). We’re going to focus on learning to love the unpolished nature of the blogging, and embrace its work-in-progress-ness, and there will be lots of writing exercises to get students used to blogging efficiently. We’re going to explore using blogging in a way that fits neatly into your life, and even how blogging can make you live your life a bit better. I look forward to good discussion, sharing of experiences, lots of inspiring blog reading, and delving into the history of this fascinating medium as we all move forward as part of its future.

August 21, 2014

Family Happiness

I reread Laurie Colwin last week, the novel, Family Happiness. And I am still thinking about “chicklit” (a term I dislike, because I’d never actually call a human person a “chick”) and how I’ve changed my mind about it. The problem with chicklit, I used to think, was that so much of it was shallow and silly and that important books kept being undermined by being shushed away into that category. I used to agree with authors who’d protest that any book about women and relationships was automatically written off as “chicklit”, and also that it was a travesty how women’s fiction was always pushed to the margins. I wrote an entire essay about this, which referenced the line from Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own: “This is an important book, the critic assumes, because it deals with war. This is an insignificant book because it deals with women in a drawing-room. A scene in a battlefield is more important than a scene in a shop – everywhere and much more subtly the difference of value persists.”

I reread Laurie Colwin last week, the novel, Family Happiness. And I am still thinking about “chicklit” (a term I dislike, because I’d never actually call a human person a “chick”) and how I’ve changed my mind about it. The problem with chicklit, I used to think, was that so much of it was shallow and silly and that important books kept being undermined by being shushed away into that category. I used to agree with authors who’d protest that any book about women and relationships was automatically written off as “chicklit”, and also that it was a travesty how women’s fiction was always pushed to the margins. I wrote an entire essay about this, which referenced the line from Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own: “This is an important book, the critic assumes, because it deals with war. This is an insignificant book because it deals with women in a drawing-room. A scene in a battlefield is more important than a scene in a shop – everywhere and much more subtly the difference of value persists.”

I still think that it’s true that women’s fiction gets pushed to the margins, but I’ve recently realized that this has nothing to do with chicklit. I have recently determined, in the past few weeks as I’ve reread To the Lighthouse, and Family Happiness, and as I’m reading Caroline Adderson’s new novel, Ellen in Pieces, right this very minute* (nearly) that there is indeed a way to write about women and relations, to write women’s fiction (for I emphatically believe that there is such a thing, and that literature is all the better for it) that will never be confused for chicklit ever.

The key, of course, is to subvert readers’ expectations, to resist the formula from which chicklit is concocted. I’m thinking about Laurie Colwin, especially, whose subversion is oh-so-subtle that undiscerning readers might miss it, but it’s there. It’s not to resist happy endings, necessarily, but to acknowledge that happiness is complicated, and endings are only relative. Colwin’s writing doesn’t hinge on “issues” or crises to propel her plots, and some might protest that Laurie Colwin doesn’t plot at all (just as Jennifer Weiner** took down Claire Messud’s The Woman Upstairs for not having a driving plot, for failing to conform to chicklit’s basic requirements, as if that somehow makes it less of a book). Indeed, her books are full of upper-middle-class women sitting on lush sofas wearing exquisite worn cardigans and turning their minds over and over again. There is pages of this. And I love it. There are no villains. Everybody is just conflicted and deeply flawed, and when they run into one another, things happen (and those things are often further conversations).

Colwin walks this narrow line between light and substance, and I think the effect of lightness comes from so much visual light—illumination, brightness, joy—and this is far from the same thing as shallow. She has been compared to Jane Austen, which I agree with, but I’m not nuts about Jane Austen, so I’m conflicted. I have this suspicion that if I came at it the other way though—reading Jane Austen with a view to her being a bit like Laurie Colwin—I could come to a new appreciation. Either way, Laurie Colwin isn’t chicklit, even though her characters are neurotic and wear specific shoes. They’re books without a template, my vague Austen references aside. Immediately readable, but as with Woolf and Adderson (though on a more subtle level), Colwin is trying to push the novel to be something more, beyond its own limits, to get life to fit inside.

How do you tell a story about the many sides of happiness? Of love?

There is a place for formulaic books, and they certainly have their legions of readers, though I no longer count myself among them. (This isn’t true. I love detective fiction. But maybe the difference is that the very formula for detective fiction is to surprise its readers. As with the best of literary fiction, you rarely known who’s going to come around the next corner.) I just don’t have the patience anymore for a book that’s going to turn out exactly as I expect. I read that book already. I want the unfamiliar, which can be breezy (Maria Semple, Laurie Colwin) or more dense (Adderson, Woolf), or a thousand other things, but it isn’t chicklit, which reduces women and their lives to types and tropes. Whose very trademarks are endings that are always going to be tidy.

“I just have a very hard time seeing entertainment as a bad thing,” said Jennifer Weiner in her interview with Rebecca Mead. But just because something isn’t a bad thing doesn’t make it literature.

*This sentence was true on Saturday, when I wrote it.

**It occurs to me now that the two books by Jennifer Weiner I enjoyed most were Fly Away Home and Goodnight Nobody, both of which were probably her most formula defiant. And maybe her point is that nobody noticed these distinctions, so she gave up even trying, which is why “[i]n later novels, she decided to ‘give my characters the thing that none of us get, which is the promise that it’s going to be O.K.’”

*** Also, speaking of worn-out templates, I basically wrote about this exact same thing two years ago. I am not sure why I can’t just get over it, but then again, I’m not the only one.

August 20, 2014

The Pyrex is Multiplying

The bowls on the right were given to me by Amy Lavender Harris, who awakened me to the wonders of Pyrex. And then I found the dish on the left on the street last week, the bowl in the middle today at Value Village, and I do fear that this might be becoming a habit… I’ve got a ways to go though.

August 19, 2014

Wild Libraries: Fort York

Yesterday, we took a trip on the streetcar to the newest (and 99th!) branch of the Toronto Public Library, the Fort York Library at the foot of Bathurst Street, a place that is helping to turn this former no-man’s land between the rail-lines and the waterfront into an actual neighbourhood. A bright, airy building with floor to ceiling windows, Fort York Library is a transport vehicle-loving toddler’s paradise, actually, with streetcars and cement-mixers rumbling over the Bathurst Bridge, trains running by to the north, and cars on the Gardiner Expressway whizzing by overhead. Not to mention condo towers going up all around us, cranes in the air, the CN tower so close—what a spectacular view of the city!

Yesterday, we took a trip on the streetcar to the newest (and 99th!) branch of the Toronto Public Library, the Fort York Library at the foot of Bathurst Street, a place that is helping to turn this former no-man’s land between the rail-lines and the waterfront into an actual neighbourhood. A bright, airy building with floor to ceiling windows, Fort York Library is a transport vehicle-loving toddler’s paradise, actually, with streetcars and cement-mixers rumbling over the Bathurst Bridge, trains running by to the north, and cars on the Gardiner Expressway whizzing by overhead. Not to mention condo towers going up all around us, cranes in the air, the CN tower so close—what a spectacular view of the city!

We walked in and were drawn to the views, and then to the new books on display in the foyer (and the great thing about a new library is that every book is a new book, and it was an excellent selection of new releases and classics, nary a dog-ear among them yet). And then Harriet and Iris made their way into the kids’ section, where they felt immediately at home.

Harriet was pleased to find a Superman picture book, and I tried to read it to her, all the while chasing Iris around the library. (I have found that visiting the library with both children on my own is a pretty ridiculous experience.) Both girls had fun climbing in the letters and picking books off the shelves, and recognizing some of their favourites among the collection.

And then Iris discovered there was a staircase, and so of course, she had to climb it. Big Sister led the way.

They spun around in the spiffy red chairs and didn’t annoy the other patrons too much.

We were intrigued by the sight of the 3-D printer, and the objects it has made. Lots of space for reading, and group and individual study up there on the second floor too, and a really nice selection of books for teens, brand new gorgeous art books and graphic novels.

When it was time to go, Harriet signed her Superman book out.

And then we took a selfie as we waited for the streetcar, which delivered us home just in time for lunch.

August 19, 2014

“If Life Gave Me Lemons” at Joyland

Today, a little dream came true. My short story, “If Life Gave Me Lemons”, has been published at Joyland. It’s a story about unrequited love, finding yourself, the bizarre culture of English teachers in Japan, and all the ways we fool ourselves. I love this story, not just because it’s part-ode to my life in Japan more than 10 years ago, though the lovingness of that ode is mostly hidden. But it’s there. So I’m so pleased that the story has found a home, and what a home it is. Thanks to Kathryn Mockler for her great edits, and to the Joyland team for making such a fantastic space online. I’m so thrilled to be a part of it.

Today, a little dream came true. My short story, “If Life Gave Me Lemons”, has been published at Joyland. It’s a story about unrequited love, finding yourself, the bizarre culture of English teachers in Japan, and all the ways we fool ourselves. I love this story, not just because it’s part-ode to my life in Japan more than 10 years ago, though the lovingness of that ode is mostly hidden. But it’s there. So I’m so pleased that the story has found a home, and what a home it is. Thanks to Kathryn Mockler for her great edits, and to the Joyland team for making such a fantastic space online. I’m so thrilled to be a part of it.

August 18, 2014

Ellen in Pieces by Caroline Adderson

Caroline Adderson’s Ellen in Pieces is the novel we’ve all been waiting for. Me, because I’ve been reading pieces of Ellen in Pieces in journals and magazines for the last few years, and hearing rumours they’d culminate in an actual book, and how often are one’s longings so perfectly satisfied? And you’ve been waiting for this book, because I promise that it’s one of the best you’ll read this year. Devastating, wonderful and brilliant. Because aren’t you always looking for a book to apply such adjectives to? Because I’ve been longing to read this book for years, and when I did, it was even better than I’d hoped.

Caroline Adderson’s Ellen in Pieces is the novel we’ve all been waiting for. Me, because I’ve been reading pieces of Ellen in Pieces in journals and magazines for the last few years, and hearing rumours they’d culminate in an actual book, and how often are one’s longings so perfectly satisfied? And you’ve been waiting for this book, because I promise that it’s one of the best you’ll read this year. Devastating, wonderful and brilliant. Because aren’t you always looking for a book to apply such adjectives to? Because I’ve been longing to read this book for years, and when I did, it was even better than I’d hoped.

It’s a novel in stories, or a collection of linked stories, or maybe a novel comprised of fragments, which is more like a life is than most novels I’ve ever read. The first three “chapters,” I’d read previously, and through which I’d become entranced with Adderson’s character, Ellen McGinty, divorced, determined, blundering, flawed, impulsive, hated, and loved. Because it’s rare to encounter such a character in fiction, a woman in the middle years of her life, a woman who is not a type, who has history, is unsure of what to do with her present, who has a body, experiences lust, gets tired, loves her children, cannot stand her children, has friends, fights with her friends, who is herself with such remarkable specificity—”Ellenish” is a term applied at one point in the book, and I knew exactly what they meant. It is rare that a character is so vividly realized—so familiar and yet utterly original at once.

Caroline Adderson pays attention to words, which are as specific as her characters. No one else would write a sentence like, “A melting weakness overtook her and she remembered all those years ago, not here but in Ellen’s North Vancouver kitchen, how he glissaded out of the way so Georgia could set down her platter of blintzes.” A platter of blintzes—has there ever been such a thing? The world reinvented through Adderson’s extraordinary, euphonic vocabulary.

In the first chapter, “I Feel Lousy”, Ellen discover that her younger daughter, not even the disappointing one, is pregnant, which evokes memories of her own troubled past, an accidental pregnancy with her ex-husband, the terrible, awful burden of motherhood, single motherhood in particular, and the lengths that a mother will go to—this mother in particular—for her daughter’s sake. “Poppycock” finds us a few years into the future, Ellen’s estranged father on her doorstep, obviously suffering from some kind of malady and she’s horrified to find him but also bowled over because he wants her, he needs her. She’d assumed her family had written her off altogether since she’d tried to sleep with her brother-in-law at her father’s 50th birthday years before. But the past, just like the present, turns out to be more complicated than that, and the reappearance of her father is a gift that comes with a shadow, a particularly long one.

And if you think that ending is devastating, read “Ellen-Celine, Celine-Ellen” next, about Ellen and her two friends whose relationship was forged at pre-natal class years ago, Ellen all alone because her asshole husband Larry had just abandoned her (the first time). The three stay close in the decades to follow, Ellen and Celine taking a trip to Europe together, which is ill-advised, so say their other friend, Georgia, and also Ellen’s hairdresser, Tony, because Ellen and Celine spend much of their friendship not being able to stand each other, a situated not mitigated by their strong personalities, and also that of the three friends who’d met in pre-natal class, it had been Celine’s baby that died.

Have I conveyed that these stories of death and crisis, all the drama of a life, are also funny? Adderson portrays human behaviour at the intersection of heroism and buffoonery, or else just irritability, to much effect. There’s a subtlety at work here. There are lines that are going to come along and break your heart.

The next few stories are more concerned with the present, pieces fitting more closely together. Ellen begins to find herself—her daughters are settling down, or else calming down; she sells her house; she takes up pottery again; after years of searching, she is learning to be present. She also starts sleeping with a young man who is her daughters’ age, which doesn’t hurt. She thinks she’s beginning to get over her ex-husband, Larry, whose desertion has wrung her heart for years and years.

One chapter is from the point of view of Matt, Ellen’s young lover, who is using Ellen to escape from his own troubled domestic situation. Another by Ellen’s older daughter, Mimi, who has overcome her problems with addiction but is still searching for something to hold onto, and still running from her mother too, whose presence is still vividly felt even from halfway across the country in Toronto, currently in the midst of a garbage strike. (Mimi traces back most of her problems to having once discovered her mother in bed with her grade-five teacher, whom she’d been in love with. Until that point.) Another word in this chapter, “orrery”, which recurs at the end of the story as Mimi rolls down a car window using a similar device. “She saw the moon, the faint stars vying for attention against the glare of human habitation. Pluto was up there somewhere, that small cold outcast planet far away. But there were people who still believed in it, people who wished it well.”

If the story doesn’t devastate you, I promise that the prose will.

At the end of this chapter, Mimi finally gets an inkling of why her mother is who she is, with the aid of a handy Bryan Adams lyric. Maternal ambivalence is a two-way street, and Adderson’s is a gut-wrenching depiction of its flip side. And then in the next chapter, “Mother-eye—the curse cast on every birthing woman, the hex of self-sacrificing empathy. I will see your pain, but you will never see mine.”

It’s at the end of this chapter when Ellen is diagnosed with breast cancer, and I’m going to tell you this, tell you this straight: Ellen dies.

I am telling you this because it’s revealed anyway in a tiny sentence on the back of the book (“…we watch Ellen negotiate the last year of her tumultuous life as the pieces of who she is finally come together.”), and in the epigraph as well, and I am telling you this because if you aren’t prepared, it might just be too terrible to take. When was the last time an author dared to kill off the central character in her novel and not even at the end of her novel…

…and of course, Virginia Woolf did, in To the Lighthouse, which I read last month, and which I see as having all kinds of parallels with Adderson’s book, although the two vary greatly in style (and Adderson’s prose is devourable, while Woolf’s must be savoured in measured portions). The notion of “time passes” and that we see a character through the eyes of those around her, the mixture of love and dislike and what lies between which makes up most relationships, and she isn’t even knowable to herself, because who has ever been so pinned down? That she a person whom people assemble around, in all her flaws and fallibility. If she is a solar system, here is the sun, and what happens after the light goes out?

The death scene is sublime, written from the perspective of Ellen’s young grandson, who has his own problems, and when I came to the paragraph break, I put down the book and sobbed and sobbed, and had to go find someone to comfort me—it’s rare that text on a page is ever this affecting. I was devastated, but also amazed at the beauty of the scene, of Adderson’s writing—it was perfect. Masterful.

In the final stories of the book, Ellen’s friends and family gather around her, offering richer perspectives on the scenes we’ve already read. I was especially besotted with “The Something Amendment,” from the perspective of Georgia, who is the third in Ellen’s friendship with Celine. We’ve previously known Georgia through her telephone conversations with Ellen, her jolly husband Gary chiming in from the background. As ever, however, the reality of life is more complicated than can be discerned from down a telephone wire, and Georgia’s own relationship with Ellen is different from even what Ellen suspects, and one of the great achievements of Adderson’s book, I think, is her rich portrayal of decades-long female friendships, the betrayals and compromises that are implicit in such relationships.

If I have to go out of my way to find a criticism of the book, it would be that the Ellen herself is so compelling that the chapters in which she’s at a distance are not as much—the half-grownness of Ellen’s lover is so bland compared to the presence of Ellen in her prime, although the characterization of him at home with his family is vivid, rich and surprising. Or maybe it’s just that I think that Ellen could have done better?

I don’t hate that she died. I wish she hadn’t, but I also didn’t feel like Adderson was using cancer or death as a plot device, to manipulate her characters or (worse!) to manipulate her reader. If its confrontation with cancer and mortality, Ellen in Pieces is a companion to Oh, My Darling by Shaena Lambert, which I read last year (and Lambert is thanked in Adderson’s acknowledgements; they share a publisher). It’s a brave take on things, really, but typical, because the exquisite nature of the entire book comes from Adderson defying her readers’ expectations, surprising you with every line, with every turn of the page.

August 12, 2014

Summer of the Yellow Dress

In most of our photos from this summer so far, a memorable (much) recurring character has been my yellow polkadot dress, which is one of the few things I own that always garners compliments from strangers. I bought the dress at a secondhand store at the end of May, which was surprising because I’m sort of between bodies right now and clothing is an awkward fit. So it was shocking to encounter this Donna Karan shift dress for $30, and then the yellow polkadot dress for $20, which I can even breastfeed in if I’m unabashed about having my boobs out.

The yellow dress was a strange purchase for me–I’ve never worn anything yellow before. I am very much partial to red and blacks, to fuchsia if I’m feeling like some colour. But the yellow dress appealed to me because it looked like something Harriet would wear. Yellow is her favourite colour, and she’s zealously devoted to it, still, even though she has recently consented to be served dinner on a plate that is another colour (if necessary). When I wear yellow, I look even more sallow than I actually am, so I’ve always avoided it, while celebrating Harriet’s affinity for it. Hooray for a little girl whose favourite colour is anything but pink.

But this dress… “What would Harriet do?” I wondered. Obviously, she would buy it, and insist on wearing it to bed, and while I didn’t go that far, I bought it and even put it on. “What do you think?” I asked my family, and they loved it. It’s kind of a weird dress with a ruffly colour, one that’s meant to be worn off the shoulder, I think, but I don’t do that because I am not a 1970s’ bridesmaid. It’s a wee bit too tight (but what isn’t these days) but the cut is flattering. And it turns out that I look not so terrible in yellow after all, or at least not once summer has arrived and the sunshine has kissed my face a bit.

And it’s a lesson I think, as well as a fortunate fashion tale (because it could well have gone the other way). That I can learn a little something by taking a leap and seeing the world through Harriet’s eyes. That something might be gained by aspiring to be just a little more like she is.

I am thinking of taking up her practice of lying on the sidewalk and screaming and kicking whenever I’m hungry or tired…