July 23, 2015

Holiday Reads

We leave for the cottage on Saturday, and obviously we are not remotely packed, except my stack of books which I’ve had ready for weeks. Heartburn by Nora Ephron, a battered copy I found somewhere recently. I read it long ago but want to read it again as part of my research into funny woman authors. Still Life by Louise Penny, which was the first Gamache mystery. I’ve never read it before, and I always read Louise Penny at the cottage, and it will be good prep for the new Gamache book out later next month. The Home by Penelope Mortimer, who I was reminded of when my Book Club comrade sent this link, and I’ve wanted to read this title since seeing it referenced in Carol Shields and Blanche Howard’s letters. Shine On, Bright and Dangerous Object, by Laurie Colwin, another reread, for funny women reasons and because it’s Laurie Colwin. The Giant’s House, by Elizabeth McCracken, because I am nostalgic for when I read her Thunderstruck last summer. And a reread of Barbara Pym’s Some Tame Gazelle, because what is a summer without a novel by Barbara Pym?

July 22, 2015

That’s what makes The M Word so surprising…

“That’s what makes The M Word so surprising, and also moving, gripping, funny, and, occasionally, really uncomfortable to read: the writers put it all on the table, all the confusion, ambivalence, difficulty, suffering, hope, despair, and insight that swirl around people’s different experiences with motherhood, whether they are or aren’t mothers, however motherhood is defined, and whether their situation arose from choice or accident, gift or tragedy. As many of the writers observe, there’s a popular public story about motherhood that is all bliss, smiles, and cuddles. For many of them, there is plenty of bliss, but that’s rarely the whole story and often not the story at all. The M Word doesn’t try to tell one story: it allows, even insists, on the coexistence of many different ones.”

“That’s what makes The M Word so surprising, and also moving, gripping, funny, and, occasionally, really uncomfortable to read: the writers put it all on the table, all the confusion, ambivalence, difficulty, suffering, hope, despair, and insight that swirl around people’s different experiences with motherhood, whether they are or aren’t mothers, however motherhood is defined, and whether their situation arose from choice or accident, gift or tragedy. As many of the writers observe, there’s a popular public story about motherhood that is all bliss, smiles, and cuddles. For many of them, there is plenty of bliss, but that’s rarely the whole story and often not the story at all. The M Word doesn’t try to tell one story: it allows, even insists, on the coexistence of many different ones.”

Many thanks to Rohan Maitzen for a smart and thoughtful review of The M Word. Maitzen is one of my favourite literary critics and I love reading her reviews, and so to encounter her review of my book is really overwhelming. And fantastic.

July 21, 2015

Unfathomable Doorknobs

Tonight my roommate from first year university, who I haven’t seen in fifteen years, walked past me as I stood in front of my house. It turns out she lives around the corner. It also turned out that she was holding a doorknob, because it had just fallen off her door, so she couldn’t get into her house. And it turned out that I was standing outside of her house with a box of tools, because we’d just finished lowering the seat on Harriet’s new bike. So we went over to see if we could help—we don’t know how to fix broken doorknobs either but the tools were something. And they were, because Stuart got the door open with a pair of pliers.

And afterwards, we reflected on that. What would you think if you were watching a movie, say, about somebody who is walking down the street holding a doorknob. And their salvation would turn out to be their roommate from nearly twenty years ago who just happens to be standing on the sidewalk holding a pair of pliers? How unlikely would that plot point seem?

For sheer unfathomability, fiction’s got nothing on the world.

July 19, 2015

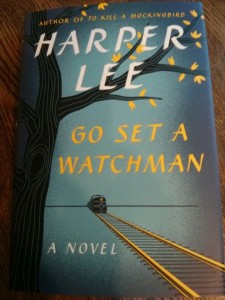

On Go Set a Watchman

Good news, if you are one who has constructed your identity along the lines of, “Everything I need to know I learned from Atticus Finch.” Because, contrary to what you may have heard, his wisdom features in Go Set a Watchman, Harper Lee’s new old book, her second book that is actually her first book and which is perhaps not a book at all but merely a draft of one. Lines like, “Hypocrites have just as much right to live in this world as anybody.” And also, “You must see things as they are, as well as what they should be.” Go Set a Watchman is not an incredible novel, though I liked reading it well enough, but it’s a remarkable artifact. (Confession: I may not have bothered reading it were the cover not so wonderful, so terrifically vintage.) I feel okay about reading it as rumours of Harper Lee’s lucidity seem fairly convincing, and I love when book news is so huge—on Tuesday, Watchman was on the six o’clock news. Book sales are good in general too, and so. Scout Finch grows up to be Midge from Mad Men—it’s kind of a amazing. And this Atticus, if he is in fact the same Atticus we know from To Kill a Mockingbird (and keep in mind that he is not Gregory Peck in any case) is indeed a racist, though I wasn’t as disturbed by his views as some readers have been because a) I live in the world and I am well aware that plenty of people think this way (and closer to home, his views about the backwardness of Black communities are identical to those I’ve heard about First Nations communities in my own country) and b) I know he is a fictional character. And it baffles me how readers seem to be so bothered by having the fictionalness of fictional creations pointed out to them (in this book, in incongruities between Attitcuses, or in Kate Atkinson’s God in Ruins at her book’s surprising twist at the end). To me, the fictionalness of a fiction is its most compelling characteristic. I love when a fictional universe is so absolutely rendered that I can see right to its edges. And so I am more interested in two Attitcuses and the two novels than I am betrayed or dismayed by them or their incongruences. Atticus Finch was never my hero. I have read the book more times than I’ve seen the movie, and for me, it’s Scout. Not to undermine the Atticus devotees or to suggest that Mockingbird isn’t a ridiculously good novel, because it is. I’ve read it at least once in the last decade and couldn’t believe how good it was. But then I didn’t reread it last week, which is key. Last week I was rereading a pretty unsatisfactory novel published recently (and it wasn’t even a first draft) so it was this to which I compared Watchman when I read it, and not To Kill a Mockingbird. It is possible that to be as good as or better than To Kill a Mockingbird is an unfair thing to demand of any book, no matter who wrote it.

Good news, if you are one who has constructed your identity along the lines of, “Everything I need to know I learned from Atticus Finch.” Because, contrary to what you may have heard, his wisdom features in Go Set a Watchman, Harper Lee’s new old book, her second book that is actually her first book and which is perhaps not a book at all but merely a draft of one. Lines like, “Hypocrites have just as much right to live in this world as anybody.” And also, “You must see things as they are, as well as what they should be.” Go Set a Watchman is not an incredible novel, though I liked reading it well enough, but it’s a remarkable artifact. (Confession: I may not have bothered reading it were the cover not so wonderful, so terrifically vintage.) I feel okay about reading it as rumours of Harper Lee’s lucidity seem fairly convincing, and I love when book news is so huge—on Tuesday, Watchman was on the six o’clock news. Book sales are good in general too, and so. Scout Finch grows up to be Midge from Mad Men—it’s kind of a amazing. And this Atticus, if he is in fact the same Atticus we know from To Kill a Mockingbird (and keep in mind that he is not Gregory Peck in any case) is indeed a racist, though I wasn’t as disturbed by his views as some readers have been because a) I live in the world and I am well aware that plenty of people think this way (and closer to home, his views about the backwardness of Black communities are identical to those I’ve heard about First Nations communities in my own country) and b) I know he is a fictional character. And it baffles me how readers seem to be so bothered by having the fictionalness of fictional creations pointed out to them (in this book, in incongruities between Attitcuses, or in Kate Atkinson’s God in Ruins at her book’s surprising twist at the end). To me, the fictionalness of a fiction is its most compelling characteristic. I love when a fictional universe is so absolutely rendered that I can see right to its edges. And so I am more interested in two Attitcuses and the two novels than I am betrayed or dismayed by them or their incongruences. Atticus Finch was never my hero. I have read the book more times than I’ve seen the movie, and for me, it’s Scout. Not to undermine the Atticus devotees or to suggest that Mockingbird isn’t a ridiculously good novel, because it is. I’ve read it at least once in the last decade and couldn’t believe how good it was. But then I didn’t reread it last week, which is key. Last week I was rereading a pretty unsatisfactory novel published recently (and it wasn’t even a first draft) so it was this to which I compared Watchman when I read it, and not To Kill a Mockingbird. It is possible that to be as good as or better than To Kill a Mockingbird is an unfair thing to demand of any book, no matter who wrote it.

- Read Hadley Freeman’s “With critics like these, it’s no wonder Harper Lee stayed silent”

- Lawrence Hill’s review in the Globe is wonderful. “But it is a pity that Go Set a Watchman was not published in the 1950s, when it would have shaken up readers, provoked even more calls for book bans …and accelerated public discussions of women’s sexual freedom.”

- And Heather Birrell’s review too, on what’s going on in Watchman and why Mockingbird still resonates

July 19, 2015

Summer Days

Sunday night, we are sunburned, all of us (oops) and everything is gritty with sand. On the cusp of a new week, a summer going swimmingly, but much too fast. Last week Harriet began the first of two weeks of day-camp at the museum, just for the afternoons, and she’s having a great time. She comes home and tells us stories about Hatshepsut and how blacksmiths fashioned knights’ armour. We’re enjoying our mornings together, hanging out with friends and going to the library, but there has been no time to clean the house and it’s become a disaster. All the sand we brought home today isn’t helping. And our weeks are hung on a routine that includes the farmer’s market, soccer, hammock afternoons. Yesterday for the second Saturday in a row, we went to Christie Pits pool to cool off from the heat, and it was perfect, straight out of Swimming Swimming. Though it was still plenty hot when we went to bed, and got even hotter when we lost power at 1am, our trusty box fans silenced. Out the window the sky was so bright, and I decided there’d been some kind of disaster, or that this was going to be a blackout lasting days and in our attic bedroom it would only get hotter and hotter. Although lights in tall buildings on the horizon suggested otherwise, but my mind was taking me to crazy places. Only settling down when Harriet woke up at 3 concerned that she’d gone blind like Mary from Little House on the Prairie, because she couldn’t see anything. By this point, Iris had taken over my spot in bed so I went to sleep on the couch, awakened by Harriet and every electrical appliance in the house when the power came back on around 4. At approximately 4:46, the sunrise began, and I watched it from my living room window, and the night was declared an official disaster.

Sunday night, we are sunburned, all of us (oops) and everything is gritty with sand. On the cusp of a new week, a summer going swimmingly, but much too fast. Last week Harriet began the first of two weeks of day-camp at the museum, just for the afternoons, and she’s having a great time. She comes home and tells us stories about Hatshepsut and how blacksmiths fashioned knights’ armour. We’re enjoying our mornings together, hanging out with friends and going to the library, but there has been no time to clean the house and it’s become a disaster. All the sand we brought home today isn’t helping. And our weeks are hung on a routine that includes the farmer’s market, soccer, hammock afternoons. Yesterday for the second Saturday in a row, we went to Christie Pits pool to cool off from the heat, and it was perfect, straight out of Swimming Swimming. Though it was still plenty hot when we went to bed, and got even hotter when we lost power at 1am, our trusty box fans silenced. Out the window the sky was so bright, and I decided there’d been some kind of disaster, or that this was going to be a blackout lasting days and in our attic bedroom it would only get hotter and hotter. Although lights in tall buildings on the horizon suggested otherwise, but my mind was taking me to crazy places. Only settling down when Harriet woke up at 3 concerned that she’d gone blind like Mary from Little House on the Prairie, because she couldn’t see anything. By this point, Iris had taken over my spot in bed so I went to sleep on the couch, awakened by Harriet and every electrical appliance in the house when the power came back on around 4. At approximately 4:46, the sunrise began, and I watched it from my living room window, and the night was declared an official disaster.

Though I roused myself for a trip to Centre Island today, a day with our friends that was so absolutely perfect. No line-ups at the ferry docks, happy children (who spent the day pretending two flat stones were smartphones via which they had fascinating conversations), splash pad fun, swimming at the beach, and lots of relaxing. Iris slept in the stroller en-route to Ward’s Island, and once we were there the thunderstorms threatened for days by the weather report finally arrived, but we were sheltered by a big old tree that mostly kept the rain off as we ate dinner and drank beer and began to feel exhaustion set in in the most terrific way. Followed by ice cream, of course, and the ferry at the dock’s so we caught it back to the mainland and that might be one of my favourite journeys in the world, how we’re always sated. How every island day always seems like the best one ever. But this one really really was.

Though I roused myself for a trip to Centre Island today, a day with our friends that was so absolutely perfect. No line-ups at the ferry docks, happy children (who spent the day pretending two flat stones were smartphones via which they had fascinating conversations), splash pad fun, swimming at the beach, and lots of relaxing. Iris slept in the stroller en-route to Ward’s Island, and once we were there the thunderstorms threatened for days by the weather report finally arrived, but we were sheltered by a big old tree that mostly kept the rain off as we ate dinner and drank beer and began to feel exhaustion set in in the most terrific way. Followed by ice cream, of course, and the ferry at the dock’s so we caught it back to the mainland and that might be one of my favourite journeys in the world, how we’re always sated. How every island day always seems like the best one ever. But this one really really was.

July 16, 2015

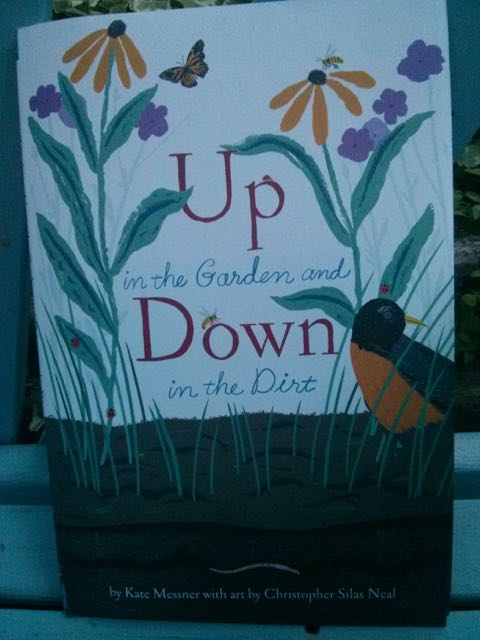

Up in the Garden and Down in the Dirt

We went to Parentbooks today to buy a birthday present for Harriet’s friend, and their gorgeous summer books table drew me right in. We ended up buying Up in the Garden and Down in the Dirt, by Kate Messner and Christopher Silas Neal, because it seemed a wonderful companion to Weeds Find a Way, because the illustrations are gorgeous, and because it was so perfectly in tune with our familial zeitgeist of late, which is all butterflies (which Iris calls “fuff-eyes”), watering cans, weeding, and getting up to our elbows in soil.

The story begins in the springtime, the earth just waking up and the crocuses poking through. Neal’s illustrations show that it’s not just up in the garden where the action is happening, but that underground a whole world exists that helps the plants to flourish.

My favourite thing about the book is how the illustrations convey the momentum of the summer garden, which is never the same two days, one plant replacing another. From crocuses, to forsythia, to magnolias, to lilacs, to irises, to linden blossoms, and onto cosmos. It’s like time, spilling over, uncontainable. The kind of thing I never noticed before I started paying attention.

Messner shows the garden as a place of fun and play as well as labour, her young protagonist cooling off from the summer heat by being sprayed by her Nana’s garden hose. While, “Down in the dirt, water soaks deep. Roots drink it in, and a long legged spider stilt-walks over the streams.”

The silhouettes at the end are particularly striking, showing that the nocturnal world—bats!—has its own role to play in helping with the garden. On the next page, there is even a skunk, an animal which—according to the book’s fascinating glossary—is actually a garden helper. Who knew? “Like bats, skunks are nighttime predators that gobble garden pests after dark. Skunks love grubs and slugs.” Ants too—I had no idea. They help to pollinate plants and air the soil with their tunnelling. Harriet and I were both gripped by these facts. It is nice to find a book that can teach new things to two readers who are thirty years apart.

By the end of the book, it is fall, harvest time. Much of the action is taking place underground again, as the pumpkins are nearly ready and the cold is near. And in winter, the story tells us, “a whole new garden sleeps down in the dirt,” the tunnels and nests and animals and insects underground drawn to resemble flowers and vines in an abstract sense—pictorial subtext. It’s wonderful.

Wonderful too the way that the book makes the connection between gardens and books and reading so clear.

July 15, 2015

For Better or for Worse: The Comic Art of Lynn Johnston

It’s a familiar story: an isolated mother begins sharing stories of her family life, expressing her frustrations with domestic life and the challenges of motherhood. Building a platform out of adversity—she’d been a single mom for a while, had a fraught relationship with her own mother. Largely self-taught, not necessarily ambitious. Hard-working, yes, but credits her success to doors opening by happenstance. Her platform growing to huge audiences, but she’s still not properly respected. She’s telling stories about kids and laundry, after all. But she keeps on telling those stories for nearly three decades, her success bringing with it fame but also certain challenges: what are the ethics of writing about one’s children, one’s family? When you’ve made a career out of telling their stories but their lives are becoming separate from yours, what kids of stories do you tell instead? And how to deal with trolls, online critics out for attack who seem to forget that you’re actually a human being?

It’s a familiar story: an isolated mother begins sharing stories of her family life, expressing her frustrations with domestic life and the challenges of motherhood. Building a platform out of adversity—she’d been a single mom for a while, had a fraught relationship with her own mother. Largely self-taught, not necessarily ambitious. Hard-working, yes, but credits her success to doors opening by happenstance. Her platform growing to huge audiences, but she’s still not properly respected. She’s telling stories about kids and laundry, after all. But she keeps on telling those stories for nearly three decades, her success bringing with it fame but also certain challenges: what are the ethics of writing about one’s children, one’s family? When you’ve made a career out of telling their stories but their lives are becoming separate from yours, what kids of stories do you tell instead? And how to deal with trolls, online critics out for attack who seem to forget that you’re actually a human being?

It’s a career trajectory not so far removed from that of many popular bloggers, although Lynn Johnston’s began in the 1970s and her “platform” was the comic, “For Better or For Worse”, syndicated daily in newspapers across North America. And when I saw recently that she’d listed a book Erma Bombeck as one of her most influential reads, the whole thing made sense to me. That Johnston, like Bombeck, was one of blogging’s foremothers, and in particular with the immediacy of her strip, domestic life unfolding in real time.

Lynn Johnston’s life and career are outlined in the new book, For Better or For Worse: The Comic Art of Lynn Johnston, a book released to coincide with a retrospective of Johnston’s work on exhibit now at the Art Gallery of Sudbury until November. The book includes full colour and black and white comics from the course of Johnston’s career, as well as examples of her early work, a discussion of her influences, and notes of the creative work she’s been up to since her strip ended in 2008. It’s fascinating reading, a behind-the-scenes look at her work that’s still so familiar to me—the Pattersons, their friends and neighbours. Which, like the best blogs, is not ephemeral at all.

July 14, 2015

Nature is as careless as it is bountiful

“For nightmare, you eat wild carrot, which is Queen Anne’s lace, or you chew the black stamens of the male peony. But it was too late for prevention, and there is no cure. What root or seed will erase that scene from my mind? Fool, I thought; child, you child, you ignorant, innocent fool. What did you expect to see—angels? For it was understood in the dream that the bed full of fish was my own fault, that if I had turned away from the mating moths the hatching of their eggs wouldn’t have happened, or at least would have happened in secret, elsewhere. I brought it upon my self, this slither, this swarm.

“For nightmare, you eat wild carrot, which is Queen Anne’s lace, or you chew the black stamens of the male peony. But it was too late for prevention, and there is no cure. What root or seed will erase that scene from my mind? Fool, I thought; child, you child, you ignorant, innocent fool. What did you expect to see—angels? For it was understood in the dream that the bed full of fish was my own fault, that if I had turned away from the mating moths the hatching of their eggs wouldn’t have happened, or at least would have happened in secret, elsewhere. I brought it upon my self, this slither, this swarm.

I don’t know what it is about fecundity that so appalls. I supposed it is the teeming evidence that birth and growth, which we value, are ubiquitous and blind, that life itself is so astonishingly cheap, that nature is as careless as it is bountiful…” –Annie Dillard, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek

Although Dillard concedes that fecundity is not quite so appalling with plants. She goes on to report, with amazement, a fifteen-foot-long tree growing from the corner of a garage roof, “rooted in and living on ‘dust and cinders.'” I had forgotten about her relative comfort with, her admiration for exploding botanicals, because it’s around this time of the summer every when I spy life coming up through the cracks in the sidewalk that I think about her comment on the appallingness of fecundity—something awful in both senses of the word. When summer throws off its harness, asserting the wild. We are no tamers of it, any of us, and concrete is only incidental. The whole world is bursting with green.

Although Dillard concedes that fecundity is not quite so appalling with plants. She goes on to report, with amazement, a fifteen-foot-long tree growing from the corner of a garage roof, “rooted in and living on ‘dust and cinders.'” I had forgotten about her relative comfort with, her admiration for exploding botanicals, because it’s around this time of the summer every when I spy life coming up through the cracks in the sidewalk that I think about her comment on the appallingness of fecundity—something awful in both senses of the word. When summer throws off its harness, asserting the wild. We are no tamers of it, any of us, and concrete is only incidental. The whole world is bursting with green.

Though I am not sure there is anything careless about it. I have never encountered a force more determined.

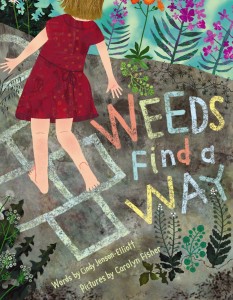

So it seemed like as good a time as any to get Weeds Find a Way out of the library, a book I recall hearing about last year when it came out but hadn’t read yet. The writer, Cindy Jensen-Elliott as full of wonder and amazement as Dillard is when it comes to the tenacity of weeds, their adaptive knack. Carolyn Fisher’s illustrations are beautiful, the book’s unique design bringing text and images together in a playful, gorgeous and illuminating experience. A glossary at the end of the book highlighting a number of common weeds, weeds so common as to be obscure if (to steal a line from poet Mary Ruefle via Heidi Julavits in The Folded Clock) “we can extend the meaning of obscure to be mean covered up by dailiness.” And who doesn’t love a book with a glossary?

So it seemed like as good a time as any to get Weeds Find a Way out of the library, a book I recall hearing about last year when it came out but hadn’t read yet. The writer, Cindy Jensen-Elliott as full of wonder and amazement as Dillard is when it comes to the tenacity of weeds, their adaptive knack. Carolyn Fisher’s illustrations are beautiful, the book’s unique design bringing text and images together in a playful, gorgeous and illuminating experience. A glossary at the end of the book highlighting a number of common weeds, weeds so common as to be obscure if (to steal a line from poet Mary Ruefle via Heidi Julavits in The Folded Clock) “we can extend the meaning of obscure to be mean covered up by dailiness.” And who doesn’t love a book with a glossary?

“Wild carrot (Daucus carota) is also known as Queen Anne’s lace. It is said to have gotten its nickname when Queen Anne of England visited Denmark and challenged the ladies there to create lace as fine as the flower of the wild carrot.”

“Wild carrot (Daucus carota) is also known as Queen Anne’s lace. It is said to have gotten its nickname when Queen Anne of England visited Denmark and challenged the ladies there to create lace as fine as the flower of the wild carrot.”

Which you can also eat for nightmare, apparently. Who knew?

July 12, 2015

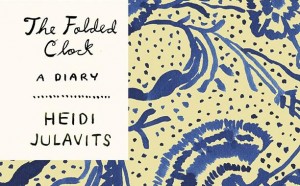

The Folded Clock: A Diary by Heidi Julavits

On Monday evening, I became overwhelmed by an irrational compulsion to go out and purchase a copy of Heidi Julavits’ new book, The Folded Clock: A Diary. Like I really needed another book, but there was something about this one—I’d been reading about it at edge of evening over the past month or so—and I not only had a car (I was visiting my parents in Peterborough where the chain bookstore is open late) but I had no one sensible to talk me out of an out-of-the-way jaunt to the bookstore past the children’s bedtime, so we went and I am so glad we did. It would be a shame if my totally irrational compulsion purchase turned to be disappointing, but it was amazing, mind-blowing. I read it once and then went through it again in my hammock yesterday, making notes, trying to figure the whole thing out. It doesn’t hurt that the cover designer is Leanne Shapton, though the only bad thing about that is that the cover got damaged in my bag and now I am a little bit devastated.

On Monday evening, I became overwhelmed by an irrational compulsion to go out and purchase a copy of Heidi Julavits’ new book, The Folded Clock: A Diary. Like I really needed another book, but there was something about this one—I’d been reading about it at edge of evening over the past month or so—and I not only had a car (I was visiting my parents in Peterborough where the chain bookstore is open late) but I had no one sensible to talk me out of an out-of-the-way jaunt to the bookstore past the children’s bedtime, so we went and I am so glad we did. It would be a shame if my totally irrational compulsion purchase turned to be disappointing, but it was amazing, mind-blowing. I read it once and then went through it again in my hammock yesterday, making notes, trying to figure the whole thing out. It doesn’t hurt that the cover designer is Leanne Shapton, though the only bad thing about that is that the cover got damaged in my bag and now I am a little bit devastated.

- Read Eula Biss’s New York Times review of The Folded Clock

- Read Heidi Julavits’ tumblr, The Keeping Society: Objects and Ephemera from The Folded Clock

The Folded Clock is a diary, though it’s a most peculiar diary. Chronology is jettisoned in favour of an arrangement of time that is and isn’t wholly random. A year’s worth of entries, each one beginning with, “Today I…” The book’s inspiration, Julavits writes, coming from an experience she had revisiting the diaries of her young, writing that she’d always imagined was her foundation as a writer, and finding instead of a foundation that, “The actual diaries revealed me to possess the mind of a paranoid tax auditor.” Time itself, she notes, had changed, becoming sweeping, a simple day insubstantial. She’d also recently borne a serious illness, one that challenged her perceptions of time: “It was no longer linear; it did not cut through my day like a road. I did not see time ahead of me. I experienced time on top of me.”

Time is a preoccupation of the entries in The Folded Clock, as evidenced by the title. Time itself not linear—many of the “Today I…” entries are actually about events decades-old, inspired by objects or experiences in the present day—and there is the issue of the construction of the book itself, which was deeply revised and shaped over another period of time divorced from the immediacy of the diary. Parenthood is another preoccupation connected to time—the impossibly tiny span of a childhood, which spins out of our control, and then conversely (but not really), the unbearable vastness of time in a child’s company: “how can this day not mostly involve my waiting for it to be over?”

Time is a preoccupation of the entries in The Folded Clock, as evidenced by the title. Time itself not linear—many of the “Today I…” entries are actually about events decades-old, inspired by objects or experiences in the present day—and there is the issue of the construction of the book itself, which was deeply revised and shaped over another period of time divorced from the immediacy of the diary. Parenthood is another preoccupation connected to time—the impossibly tiny span of a childhood, which spins out of our control, and then conversely (but not really), the unbearable vastness of time in a child’s company: “how can this day not mostly involve my waiting for it to be over?”

The diary’s various settings become familiar—the writer’s apartment in New York City, the community in Maine where Julavits, her husband and their children spend their summers, the German villa where they’re living while her husband is on a fellowship, and various artist retreats to which she escapes throughout the year. There is nothing haphazard in the entries’ arrangement, so that we’re introduced to a concept or thing or incident and will be referenced later, our knowledge taken for granted. Less obviously, the entries seem contextualized from a future vantage point so that each one takes its reader somewhere—a mini-essay every one. There is cohesion to the entire project, though the patterns are difficult to discern. Which is the point, Julavits points out, in one of the several clues she offers throughout the book pertaining to its curious construction:

“What’s on the page appears to have busted out of my head and traveled down my arms and through my fingers and my keyboard and coalesced on the screen. But it didn’t happen like that; it never happens like that.”

The Folded Clock is a book about the puzzles and mysteries of an ordinary comfortable life. For me, one of those mysteries is the way that a book—an object wholly apart from my existence, until I bought it—can appear to be reading my mind, stealing my life. (I have this experience also when I am reading Rebecca Solnit.) Like Julavits’ whole chapter about Wasted: The Preppie Murder, by Linda Wolfe, and being three fucks away from Robert Chambers—not that I have ever been such a thing, but I have a thing about that book. Or about abortions as women’s work, about how the boyfriends are always informed but they’re never there—abortions are something that happen between friends. About the internet and desire, about conscious attempts to resist the google-ization of everything—which is interesting because there is at first glance something so bloggish about Julavits’ approach, and yet the construction of her entries is so counter to blogging’s immediacy. The Folded Clock is a bit of a throwback, a project decidedly analogue.

It works because the writing is wonderful: lines like, “Worrying about originality is like worrying about the best place to hang your wall phone.” Anecdotes that start with, “Once I stole the name of a fetus.” How could you not want to read the rest? And while her prose style isn’t Didion’s, Julavits has that writer’s ability to lay down a thread and appear to be following it, while she is in fact blazing an altogether different trail. Connections, symbioses, and coincidence—all interwoven, meaningful and nothing by the by. And always, unfailingly, interesting. The question of whether male writers ever consider female writers a threat. The nature of relationships. Some of these entries made me uncomfortable, sometimes because I couldn’t identify, and other times because I could. And any diary worth its salt should garner such a response.

I loved this weird wonderful beautiful book, a book that was also easy to read in little bits—important when I was caring for my children without a break last week. A book I knew I needed before I needed it, and there is something otherworldly about the whole thing. Or perhaps I mean the opposite, that the book—with its preoccupation with objects and thingness and remarkable beauty as a thing itself—is eerily all too wordly—but then its not, it’s so rarefied, no matter how much it seems to have busted out of a head, out of the earth.

But still, it’s the kind of object one wants to go around clutching. Last week I wrote down directions to my friend’s house on a yellow post-it note that I promptly lost, mysteriously—which is another of Julavits’ preoccupations, the way that an object can dematerialize. When I found the post-it note again yesterday between the end pages and the back cover, I was not at all surprised. And I left it there. I will discover it again the next time I read the book, and of course I will remember.

July 9, 2015

Lavender

On our way back to Toronto today, we stopped at Lavanne Lavender in Campbellcroft, whose signs I’d been noting on the highway for years now. They regretted that their lavender fields weren’t quite an amazing as they should be—a nasty combination of drought and frost this spring—so admission fees were waived, but we had a great time all the same. I’m kind of their target audience, and so I went through their shop like a lavender fiend in a lavender shop. I got lotion, shortbread, honey, and a jar of Herbes de Provence—all homemade. The children had fun running up and down between the lavender plants, and we walked the labyrinth even if it wasn’t very bloomy. And then we had lunch at their pop-up cafe, which is running Thursday-Sunday all summer long. The lavender-inspired menu included a mango lavender gazpacho, lavender flavoured chicken and lamb brochettes, melon salad with lavender honey, and a lavender custard tart that blew my mind. It was delicious, and a really lovely setting. Definitely one of the most interesting pit-stops we’ve taken lately.