August 20, 2015

Preventative: The Litter I See Project

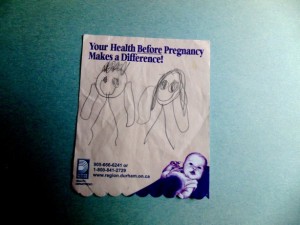

Today my short short story, “Preventative”, is up at the fantastic The Litter I See Project, a brainchild of the excellent Carin Makuz. She has enlisted a slate of Canadian writers to create a piece inspired by a piece of litter (“the litter I see”) in order to support literacy. Readers who enjoy these pieces are encouraged to make a donation to Frontier College. Find out more about the project here.

Today my short short story, “Preventative”, is up at the fantastic The Litter I See Project, a brainchild of the excellent Carin Makuz. She has enlisted a slate of Canadian writers to create a piece inspired by a piece of litter (“the litter I see”) in order to support literacy. Readers who enjoy these pieces are encouraged to make a donation to Frontier College. Find out more about the project here.

My story:

“She’s all arms and legs, that girl,” was what everybody kept saying to Myra when Teeny turned six and got gangly. Which irritated Teeny, who was not only pedantic but also sensitive to remarks about her appearance, and so she’d glare at whoever was speaking and she’d say, “That’s not even true. I have a body.” Slapping her bum to make the point, storming away, a tornado of limbs. Eventually Myra’s sister felt she had to have a word.

“That girl needs to learn to watch her tone.”

August 19, 2015

Summer Vacation Reads: The Syllabus

While it is true that the books one reads on her vacation can in fact make or break that vacation, it is essential that the reader not worry too much about all that. That she not fuss about reading books that are geographically fitting, or thematically on point; there needn’t necessarily be a syllabus for one’s vacation reading, is what I mean. And not because a syllabus is not important, but because a syllabus has a strange way of asserting itself. It’s a kind of magic, I think, how when a few random books are selected to be read one after another, they end up speaking to each other in uncanny ways, and echoing the world around their reader.

While I take full credit for reading seven books during my recent one-week summer vacation (with children, no less) full disclosure requires me to inform you that I spent 1.5 hours waiting by myself for our delayed rental car with Nora Ephron’s Heartburn in my bag the day we left, so I got a jump start on the reading. I finished that book before we arrived, but this is kind of cheating because I started it before we even got on the road. In fact, I was reading it on the subway on my way to pick up the car, strap-hanging with one hand, the book in the other, when Rachel’s analysis group gets held up by a robber, and I almost fell over with the pacing of that scene, the absurdity, surprise. The book’s mingling of comedy and tragedy is so wonderful, and the only way a writer could ever get a book like this to work so well, I decided, would be for her to be Nora Ephron. From a technical standpoint, so much is wrong with Heartburn, but it’s perfect. I also tried the Potatoes Anna recipe and it was so ridiculously delicious, and not just because it was butter-laden. I really loved this novel, which introduced what my vacation-reads thesis was ultimately to be: books about marriage, but from often-unexamined points of view. Ephron’s roman a clef about the end of a marriage taking her reader on the roller coaster ride of emotions, the will-she-stay, will-she-go, will-she-plummet-or-soar questions as Rachel navigates her heartbreak. I loved it.

And then Still Life, by Louise Penny, her first Inspector Gamache novel. Which is one of the two mysteries I read that week, neither actually according to the syllabus, but what kind of fun is consistency? Whereas Still Life is so fun, wonderfully good. (I was reading it partly in preparation for the new Gamache book that comes out next week.) Though if I had to make this novel pertain to the syllabus somehow, it would be that Louise Penny novels are books that both parties in my marriage are crazy about. Having Stuart to talk about them with is one of my favourite parts of the reading.

And then Barbara Pym, and I do love to reread her in the summer. I can never remember her titles distinctly until I reread them and it all comes back. Some Tame Gazelle is the one with a Harriet, who lives in a country parish with her sister Belinda. It is also the one with a caterpillar in the cauliflower cheese. Harriet is mad for curates and Belinda harbours an impossible old love for the Archdeacon, who is married. These longings not quite the stuff of Jane Austen (with whom Pym is so often compared) in that the novel only ends with just one wedding and not six, and neither Harriet nor Belinda are the bridal party. And yet these unrequited affections are not meaningless or unimportant: ”Some tame gazelle, or some gentle dove: / Something to love, oh, something to love.” Marriage need not be the end of the story for a life to be full and complete.

Next was The Giant’s House, by Elizabeth McCracken, whose Thunderstruck was one of my favourite books of last year. I didn’t like it as much as the short stories—the sadness brought me down and I found that the narrator didn’t give us enough of herself, when she was the most fascinating character in the book. But McCracken is wonderful, and I’ll read everything she writes. Her narrator a rather Pymmish character, a librarian who meets a young boy with giantism. Peggy is drawn to James and desperate to be part of his orbit, never mind the different in their ages or height. It’s a story with a compelling sense of place and time, and richly drawn secondary characters. Two points about the marriage: that Peggy describes herself as the product of two parents who were in love with each other, and that is a blow no child can recover from. And McCracken too describes a Pymmish arrangement, a love that was not conventional or a marriage as we’d understand it, but meaningful and profound all the same.

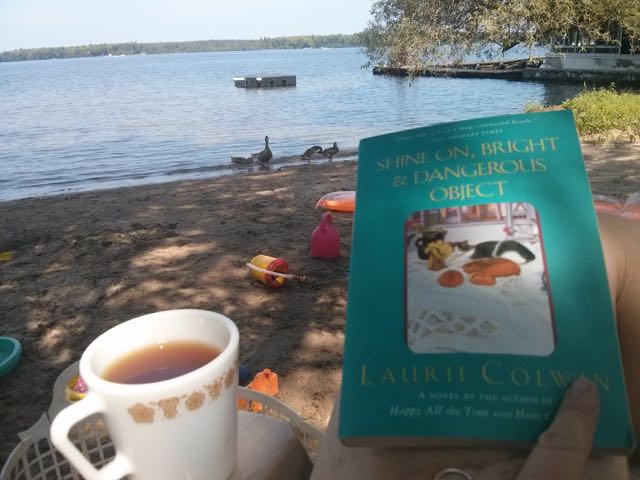

And then I read Laurie Colwin. Oh my god, Laurie Colwin. I have not reread her books in so long, and I think I was a bit too young when I read them the first time. She is so excellent and funny, and so perfectly strangely skewed. Her book, Shine On, Bright and Dangerous Object, is about a young woman who must renegotiate the terms of her life after the sudden death of her husband in a sailing accident. A husband with whom, she admits, she probably would have divorced—he was young and reckless, and she came along for the ride. So yes, she is devastated, but the ride is over, and what now? The narrative zeroing in on all the parts lesser writers might skip, the seemingly mundane. Colin has unconventional views about marriage and fidelity, and oh yes, she believes in love, but life is as complicated as her characters’ psyches. I loved this book and devoured it, and reread Goodbye Without Leaving last week and then ordered Passion and Affect and The Lone Pilgrim right after, which are the two remaining Laurie Colwin novels I haven’t read yet. Oh, you have to read her. She is so so good.

The Home, by Penelope Mortimer, was my biggest surprise. She is the most undated 1970s’ novelist ever, and I remember thinking that when I read My Friend Says It’s Bullet-Proof, but this one could have been written tomorrow. (This is the novel I have been wanting to read for years because Carol Shields and Blanche Howard wrote about it in their collected letters.) It was so funny, contemporary, surprising, and strong. About recently-divorced Eleanor who embarks upon her new life as a divorcee after 25 years of marriage, at first with wide eyes and ideas about a home where her grown children would return, her youngest son could grow up secure, where she would have parties, entertain lovers, and be free, for the first time in her life. But reality doesn’t quite measure up (and oh, there is a heartbreaking scene where she has prepared herself and her home for the arrival of a lover, with tragic results). Eleanor’s children are so distinct, loveable, terrible and annoying—I was most amused by the family’s reaction to the eldest, Marcus, a homosexual who lives in France. This was a Margaret Drabble-ish read, but also particular and so excellent. This is a book that absolutely has to be brought back into print.

And then I read Gillian Flynn’s Dark Places, which I loved, but there is no way I’m going to see the movie because it might terrify me. The book was definitely not on the syllabus, but it was so good though that I couldn’t put it down and finished before the sun went down. Which mean that I was left bookless: usually a terrifying situation. But kind of a liberating one, after seven days of mad marathon reading.

I am thoroughly incapable of reading nothing though. That night I made do with two 1980s’ Archie Double Digests, and they were fantastic.

August 19, 2015

In the continuing story of our garden planter

In the continuing story of our community garden planter, it appears that fairies have suddenly and mysteriously set up shop there.

August 17, 2015

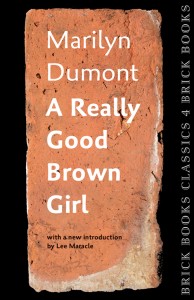

A Really Good Brown Girl, by Marilyn Dumont

I hadn’t budgeted for books at The Stop Farmers’ Market at Artscape Wychwood Barns a few weeks back, but it turned out that Pedlar Press and Brick Books were vendors (and I met Kate Cayley, whose How You Were Born I loved so much!) so I couldn’t help but pick up something. And I am so glad that the something I got turned out to be the deluxe redesign of Marilyn Dumont’s Gerald Lampert-winning debut collection, A Really Good Brown Girl. A book I read in days, which is rare for me and poetry, but I was captivated by the narrative, the language, the brute force of these poems, as well as their sense of humour, their cheek. “Squaw Poems,” about growing up Metis on the prairies, a household surrounded by “The White Judges” who waited to pounce. And never really went away. But then—

I hadn’t budgeted for books at The Stop Farmers’ Market at Artscape Wychwood Barns a few weeks back, but it turned out that Pedlar Press and Brick Books were vendors (and I met Kate Cayley, whose How You Were Born I loved so much!) so I couldn’t help but pick up something. And I am so glad that the something I got turned out to be the deluxe redesign of Marilyn Dumont’s Gerald Lampert-winning debut collection, A Really Good Brown Girl. A book I read in days, which is rare for me and poetry, but I was captivated by the narrative, the language, the brute force of these poems, as well as their sense of humour, their cheek. “Squaw Poems,” about growing up Metis on the prairies, a household surrounded by “The White Judges” who waited to pounce. And never really went away. But then—

“I am in a university classroom, an English professor corrects my spoken/ English in front of the class. I say, “really good.” He say, “You mean/ really well, don’t you?” I glare at him and say emphatically, “No I/ mean really good.”

This line giving the book its title, a double as so many of the poems show the Metis girl who hears, “You are not good enough, not good enough, obviously not good enough/ The chorus is never loud or conspicuous,/ just there.” And also connecting Dumont not just to her literal foremothers (the women raising Blue Ribbon children with the White Judges looming ) but her literary foremothers too—in her Afterword she writes of the African-American women writers who inspired her, and other Indigenous writers from all around the world. She writes of another really good brown girl in “Helen Betty Osborne”:

Betty, if I set out to write this poem about you/ it might turn out instead/to be about me.

Another poem, “Letter to Sir John A. MacDonald”:

Dear John: I’m still here and halfbreed,/ after all these years/ you’re dead, funny thing… / because you know as well as I/ that we were railroaded/ by some steel tracks that didn’t last/ and some settlers who would settle/ and it’s funny we’re still here and callin’ ourselves halfbreed.

The poems are their own context, but in this new edition they are complemented by Dumont’s Afterword, as well as with an introduction by Lee Maracle:

“No other book so exonerates us, elevates us and at the same time indicts Canada in language so eloquent it almost hurts to hear it.”

I’m so glad I finally read it.

August 16, 2015

This is Happy, by Camilla Gibb

While it is certainly true, as Joan Didion wrote, that we tell ourselves stories in order to live, it is possible that by now the phrase itself has become so hackneyed as to be a cliche, as have become gushing publisher’s copy comparing heartbreaking memoirs to Didion’s A Year of Magical Thinking. But while the good people at Doubleday Canada have resisted to the temptation to slap Camilla Gibb’s memoir, This Is Happy, with the Magical Thinking comparison, I think this the rare case in which the comparison really does apply—Gibb’s memoir is a no-holds-barred dispatch about devastating heartbreak from the frontiers of stark grief, a gut-wrenching story told from the perspective of a most cool and discerning “I”. It’s the “telling ourselves stories in order to live” in practice, Gibb, like Didion, pasting the pieces of her shattered life together, the art that emerges from the exercise.

While it is certainly true, as Joan Didion wrote, that we tell ourselves stories in order to live, it is possible that by now the phrase itself has become so hackneyed as to be a cliche, as have become gushing publisher’s copy comparing heartbreaking memoirs to Didion’s A Year of Magical Thinking. But while the good people at Doubleday Canada have resisted to the temptation to slap Camilla Gibb’s memoir, This Is Happy, with the Magical Thinking comparison, I think this the rare case in which the comparison really does apply—Gibb’s memoir is a no-holds-barred dispatch about devastating heartbreak from the frontiers of stark grief, a gut-wrenching story told from the perspective of a most cool and discerning “I”. It’s the “telling ourselves stories in order to live” in practice, Gibb, like Didion, pasting the pieces of her shattered life together, the art that emerges from the exercise.

For anyone familiar with Gibb’s fiction, much the memoir will be familiar too, so much of the former rich with autobiographical details, her first two novels in particular. It is clear that Gibb has been telling herself stories in order to live since her success with her first book in 1999, Mouthing the Words, which was also the story of a young girl from a broken home with a troubled father and plenty of trauma, mental illness, and the disillusionment of the Oxford experience. In This is Happy, Gibb goes back to her own beginnings to paint a picture of her early struggles, trying to pinpoint the moment where it all went wrong.

The happy ending was supposed to be Gibb’s marriage, which lasted ten years, to a woman who is called “Anna” in the book. A period of calm, of happiness. She does not slip into depression, she writes, she finds continued literary success. And then in her late thirties, she is surprised by a yearning to have a baby. After a painful miscarriage (though I don’t know there is any other kind), Gibb finds herself pregnant again, still tentatively so—just eight weeks along. When Anna reveals that their relationship is over, that she has fallen out of love with her. Sending Gibb into torrents of grief, which is extra-troubling because of the new life she carries inside her: this was supposed to be a beginning. Instead it’s more of the same, and Gibb fears her child growing up with the same hardships, emotional deprivations, and sense of displacement that plagued her throughout her own childhood. The damage is being done already, she feels, knowing how a fetus is meant to be affected by a mother’s stress. And she is powerless to stop it.

Except that she isn’t, which is the miracle of narrative. That it moves forward, even if one is only crawling in agony. The final third of the book is the story of Gibb’s pregnancy and experience of new motherhood, and it’s not clear for a long time that this will be a story of triumph. For most of this period, Gibb is wracked with despair, receiving special care after the baby arrives—she realizes later—not because her midwife has concerns about lactation, but because she is crying all the time. Gibb resisting a diagnosis of depression in a way I find interesting, because felt similarly when I first became a mother: that this is not depression, it just that life is terrible. Except that for Gibb, returning to antidepressants brings with it some relief. As does the support system that she has built around her as she’s put her life back together again.

In the new home that she has made for herself and her daughter, Gibb is surrounded by her long-estranged bother, an addict struggling to overcome his demons; her nanny, Tita, an immigrant from the Philippines who is waiting to be able to bring her husband to Canada to be with her; as well as friends, but not the ones she might have expected. Her brother builds her a back deck and does home renovations, she and Tita embark upon the complicated dance of an employer and employee who become much more than that. When her daughter is just a few weeks old, Gibb takes her across the country on tour for her novel, The Beauty of Humanity movement, revealing little of her pain in media interviews, though to be fair, most new mothers only ever really understand the mess they were in in retrospect anyway.

It is not a convenient trajectory: this unconventional family arrangement is not the ending either, but a moment in time. Gibb’s brother eventually leaves for Vancouver, his period of sobriety ending; Tita’s husband arrives, and they’re going to need space to become a family of their own. Gibb’s daughter gets older, a little person in her own right. Every resolution brings with it another kind of challenge, but eventually—with the help of her psychoanalyst, her unique support network, and a lot of what she’s learned about herself in the stories she’s told herself in order to live and then interrogated in order to see deeper—she finds some kind of footing:

“This is the circle that could never quite be complete… It is a story with a different ending. A story without an ending at all./ And this, I know, is happy.”

The amazing but necessary understatement of the final statement. Happiness being only an ordinary thing. And it is, and yet one must undergo a certain amount of experience before understanding that there is nothing ordinary about it—Joan Didion wrote about that in Blue Nights.

While Gibb’s own story is harrowing and awful, it emerges not as the most remarkable element of the memoir, which is instead her narrative voice, the “I” that is Didionesque. Not in the rhythms and cadence, for Gibb’s prose is excellent and entirely her own, but in the distance, the coolness, and restraint. The reader is not to imagine herself in Gibb’s shoes on that fateful day when everything changed, when she’d just purchased a freezer full of expensive fish, anticipating dinner parties and occasions unrolling into the future like a ribbon. She gives a sense of what it felt like, but that sense is not the point: the point is what does it mean? What does one make out of this kind of devastation?

And in Gibb’s case, with This is Happy, the answer is a beautiful, powerful book.

August 13, 2015

Three New Books About Loss

The Bureau of Misplaced Dads, by Eric Veille and Pauline Martin

The Bureau of Misplaced Dads, by Eric Veille and Pauline Martin

This book has a vintage vibe right down to its oranges, greens and yellows, the crosshatching, and that the illustrations remind me so much of Esphyr Slobodkina’s Caps for Sale—perhaps it’s the moustaches? It also is completely weird in that way picture books got away with back in the day. Utterly pointless, silly, absurd, and I mean it in the best way. (Maybe it’s just European?) It’s about a boy who loses his dad one morning and finds assistance at the Bureau of Misplaced Dads, where lost fathers go to wait for their children to retrieve them. (Most are in fairly good condition when they’re finally found.) Some are found same day, others have been waiting since the dawn of time. “The dads in striped sweaters hang out in the Ping-Pong room.” They aren’t allowed to play with the crocodiles, but otherwise they can do anything they please. There are two full-page spreads that are totally Wild Rumpus-inspired. The ending will satisfy anxious readers, but is just as strange as rest of it, which is to say that it involves a short cut in which the boy climbs up the ladder beside an old dog, and arrives home via a hole in the floor. Hooray for short-cuts, and books rich with strange surprises.

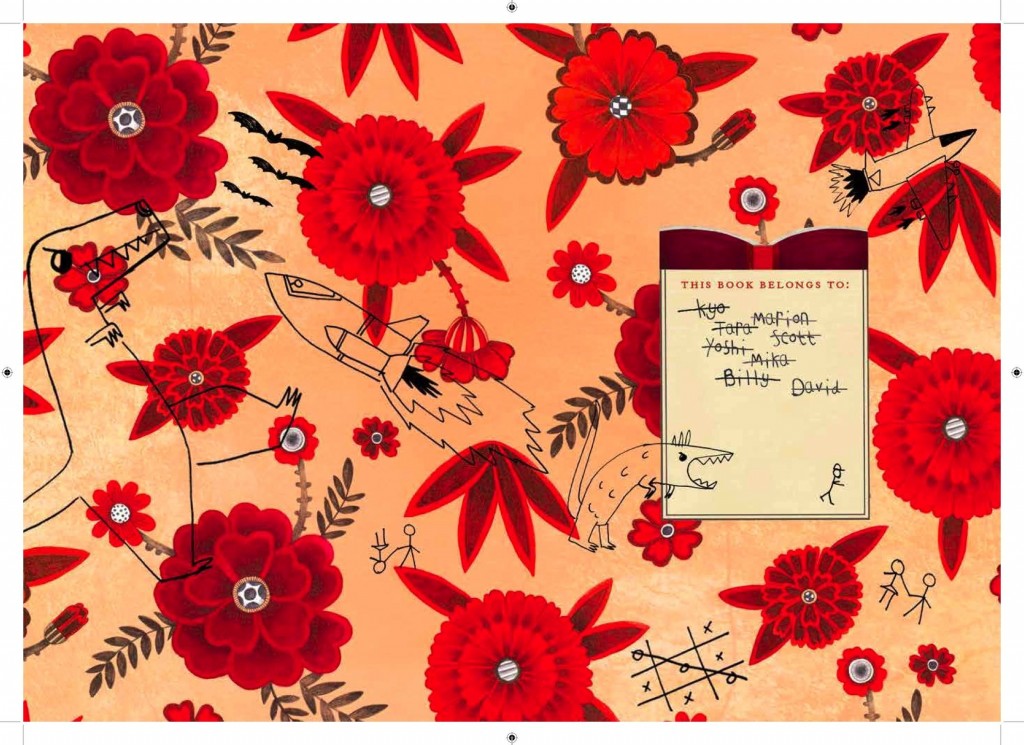

The Good Little Book, by Kyo Maclear and Marion Arbona

The Good Little Book, by Kyo Maclear and Marion Arbona

I was rhapsodizing about Kyo Maclear a couple of weeks back because she’s managed to have two books out this fall that are very different and both excellent—she’s so good! The Good Little Book is a gorgeous package, its deliberate graffiti’d bookplate and endpapers, the whole thing beautifully designed to emphasize the book as object, which connects to the story. About one book in particular that is “neither thick nor thin, popular nor unpopular. It had no shiny medals to boast of. It didn’t even own a proper jacket.” (Get it? Jacket?) But this little book finds its way into one reader’s heart, and there it stays, accompanying the reader everywhere, changing his life. Until one day the book gets lost. The boy who lost it fearing for his book in the wild, seeing as it doesn’t even have a jacket. (Ha!) But a good book, the boy learns, never really goes away, and the book itself, we learn, continues to be loved and read, as good books do. “Is this the end of the book?” is the question inked upon the final pretty floral endpaper, to which this reader knows the answer: never!

Some Things I’ve Lost, by Cybele Young

Some Things I’ve Lost, by Cybele Young

As one who has long been intrigued by the secret lives of things, I’m intrigued by Cybele Young’s new book, which is inspired by her paper sculptures. A set of keys, a roller skate, an umbrella (and I do have a fascination with literary lost umbrellas), a pair of glasses. Things that disappear (and I’ve written about that too). But: “Where there’s an end there’s a beginning,” Young’s book’s introduction tells us. “Things grow. Things change.” The books’ transformations are abstract enough as to be unpredictable and engaging, and budding artists might be inspired to make their own “some things” new.

August 11, 2015

Sistering by Jennifer Quist

It would have saved me a whole lot of trouble if Sistering, by Jennifer Quist, had had a different cover. Something pink and quirky, a decorative font, I’m thinking a pair of legs sticking out of an open grave, feet in sparkly slippers. Instead of the sombre cover the book has now, which had me imagining I was reading something deep and serious. Although the actual cover did appeal to me too—stair steps like siblings, one after the other. This was a book about five sisters, the copy told me, which put me in mind of the early ’90s melodrama Sisters starring Sela Ward and (for a season) an early George Clooney, which I was totally obsessed with when I was 12. But Sistering was more Mary Hartman than Sisters, a morbid comedy. A romp, like the cover copy says, even though there is nothing rompish about the cover image as it stands.

It would have saved me a whole lot of trouble if Sistering, by Jennifer Quist, had had a different cover. Something pink and quirky, a decorative font, I’m thinking a pair of legs sticking out of an open grave, feet in sparkly slippers. Instead of the sombre cover the book has now, which had me imagining I was reading something deep and serious. Although the actual cover did appeal to me too—stair steps like siblings, one after the other. This was a book about five sisters, the copy told me, which put me in mind of the early ’90s melodrama Sisters starring Sela Ward and (for a season) an early George Clooney, which I was totally obsessed with when I was 12. But Sistering was more Mary Hartman than Sisters, a morbid comedy. A romp, like the cover copy says, even though there is nothing rompish about the cover image as it stands.

Which meant that I was confused at the beginning of the book by the strangeness of the characters, by their unnatural behaviour, and how nobody ever remarked on it. Although the story was compelling, and the writing was good, but I kept getting caught on certain points—how Suzanne is obsessed with her mother-in-law, for one. An affliction that’s happened to no one that I’ve ever known, but her sisters take it for granted. And then things with Suzanne and her mother-in-law take a particularly weird turn when the mother-in-law dies in an accident in her home, and Suzanne responds in a way that is, um, untraditional to say the least. At this point I was still not fully cognizant of the constructs of Quist’s literary universe—confused by the cover—and so the absurdity of the situation just seemed bizarre. Until I read further (compelling story, good writing, remember?) and realized that absurdity was the very point.

Quist is no stranger to odd books about death. Her first novel, Love Letters of the Angels of Death, was completely unique and well received, though with a twist at the end that I could not bring myself to bear for personal reasons, and so I was unable to fully appreciate it. This second book has a lighter touch, but with the same morbid preoccupations—one sister runs a funeral home, another mimes her own mother-in-law’s suicide, and another owns a shop creating cemetery monuments. Both books daring to present death as part of every day life, worth writing a romp about even. And in the end, the morbidness comes to takes a back seat to the sisters themselves, who were never meant to be ordinary or “relatable” in the first place—although they’re all familiar in many ways. Sometimes scarily so.

Over the course of the novel, Suzanne loses her mother-in-law, two of the other sisters find theirs are resurrected, babies are born, marriages are broken, so is an engagement, and there is a whole lot of gossip in the meantime under the guise of concern. That the sisters and their husbands are more types than fully realized characters is part of the exercise, as to exist in a large family is to be typecast—how else is one suppose to carve out her place? The types themselves setting up the potential for absurdity as characters behave accordingly. When nobody is just ordinary, neither is the plot.

I liked this book—though it took me some time to be sure about this, because for nearly the first half, I was mostly just confused. But once I figured it out—it’s supposed to be funny—it really was. Weird and original, a dark comedy indeed—not necessarily miles away from Sela Ward and Sisters either. This one that will appeal in particular to readers who loved Trevor Cole’s Practical Jean, and to anyone who ever had a pack of sisters.

August 9, 2015

I wish there was more

We didn’t need clocks on our vacation, or calendars. The hours of the day were accounted for by the sunshine as it moved across the grass, and we had to move the hammock to keep up and remain in the shade. The days themselves were marked by the the spread of a rash down my arms, which became quite extensive because the weather was great and we were swimming every day and I am actually allergic to lake water. It’s hard out there for a sex-goddess. Anyway, the week progressed as quickly as the rash did. I read seven books, this success jump-started by our rental car pick-up being delayed and so I got to sit for 1.5 hours reading Nora Ephron’s Heartburn before we even hit the road. It was wonderful, and contains the delicious recipe for Potatoes Anna which I have since made twice. I will be writing more about my vacation reads soon.

Our week away was lunches, cruising down highway to the strains of Taylor Swift, corn on the cob, watching boats, eating butter tarts and creamsicles, playing UNO, digging holes, building castles, making smores in the oven, going out for Kawartha Dairy Ice Cream, and reading Mary Poppins. Iris was impossible and so frustratingly two that sometimes the whole endeavour was too exhausting to be vacation, but it all came together in the end, even if the morning sounds of birds outside woke her up far earlier than we would have liked. I particularly enjoyed reading vintage Archie digests and doing the pie shack shimmy (see photo above).

We came home a week ago, and spent a fun long weekend in the city hanging out with our friends. I’ve been reading some terrific new books I’m excited to be able to share with you, and trying to get work done on a big project I’m looking forward to sharing with you soon—although Iris wasn’t sleeping well at all, which has put a cramp on my “working in the evening” plans. Further cramping has ensued since my swimming rash morphed into an insane reaction this weekend, colonizing my face, which is now swollen and gross. So I am not only hideous, itchy and uncomfortable, but was prescribed super hardcore antihistamines at a walk-in clinic this morning that have rendered me totally stupid. It is possible that I’ve written this entire post in Latin, and I don’t even realize. Veni. Vidi. Itchi.

**

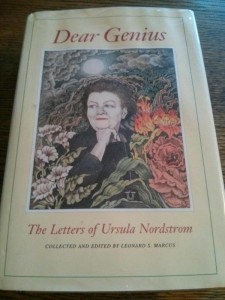

Dermatological issues aside, my only real complaint about summer is that it’s half-done. A splendid one so far. This weekend well-spent even through the rashy trauma as I compulsively read Dear Genius: The Letters of Ursula Nordstrom, which I absolutely had to purchase used after reading Rohan Maitzen’s post about it. She writes, “If you ever read a book, or were a child, or read a book to a child–if your childhood was shaped in any way by the books you read–then you should buy this book and read it immediately.” It’s the best advice I’ve followed in ages, and I’d urge you to do the same. Certainly a window into the mind of the woman behind literary classics such as Where the Wild Things Are, Harriet the Spy, Good Night Moon, Charlotte’s Web, The Carrot Seed, Harold the Purple Crayon, and others. 500 pages and I read it in three days. I wish there was more.

Dermatological issues aside, my only real complaint about summer is that it’s half-done. A splendid one so far. This weekend well-spent even through the rashy trauma as I compulsively read Dear Genius: The Letters of Ursula Nordstrom, which I absolutely had to purchase used after reading Rohan Maitzen’s post about it. She writes, “If you ever read a book, or were a child, or read a book to a child–if your childhood was shaped in any way by the books you read–then you should buy this book and read it immediately.” It’s the best advice I’ve followed in ages, and I’d urge you to do the same. Certainly a window into the mind of the woman behind literary classics such as Where the Wild Things Are, Harriet the Spy, Good Night Moon, Charlotte’s Web, The Carrot Seed, Harold the Purple Crayon, and others. 500 pages and I read it in three days. I wish there was more.

July 24, 2015

If you need me, I will be in the hammock.

Farewell, my friends. I will see you in a few weeks. And until then, I leave you this image of an avocado that has been partially eaten by a squirrel. I am impressed by the precision of how the top was sliced off, and the intricate details in the marks in the flesh left behind by tooth and claw.

(It is not often that one gets to use that expression literally. Hope this is the first and last occurrence of such a thing for me for some time.)

July 24, 2015

This Specific Ocean by Kyo Maclear and Katty Maurey

The first thing I ever read by Kyo Maclear was The Letter Opener, a novel, which I loved, and so it’s taken some time to get my mind around the idea of her as a picture book author. Even though the books themselves were very good—the brilliant Spork, and the strange and beautiful Virginia Wolf, and the even-stranger Mr Flux that has grown on us so much that I routinely pick it up and read for comfort in times of anxiety (“Sometimes change is just change”). I should have twigged to something with the amazing Julia, Child, her collaboration with one of my favourite illustrators, Julie Morstad. But no, I thought. These were just ones-0f-a-kind. Brief flourishes of excellence. No picture book writer could keep producing work that is every time so different, so smart in its concept, original and singular—each book its own perfect world. But Kyo Maclear does, and it’s so remarkable. I’m convinced finally as this fall she has two extraordinary releases, The Good Little Book, illustrated by Marian Arbona, and this one, The Specific Ocean, with Katty Maurey.

Maclear has been fortunate in her picture book career to work with some of Canada’s best illustrators, Isabelle Arsenault and Morstad among them, ensuring that her books have considerable visual appeal. Indeed, when the books have won awards, it has tended to be for their illustrations, and my own focus on her book’s images has contributed to my reluctance to give Maclear full credit for her picture book prowess, though I have long been a huge fan of her work. But with her two most recent books—each so different in illustrations and design, and so different too from her previous works—I’ve really finally come on board. In all her stunning books with their own particular style, Maclear herself is the common denominator. And she’s come far enough in her career that we can start to marvel at her oeuvre.

But, as the title suggests, it’s time to get specific, and Maclear’s work is so various that specifics are the most interesting way to discuss it. The Specific Ocean is about a young girl whose family is flying across the country for their summer vacation, but the girl doesn’t want to go with them. She wants to stay in the city and play with her friends, so when they finally do arrive at their destination beside the sea, she is resolute in her misery and refuses to enjoy herself.

It’s the ocean that finally sways her though, its formidable coldness, the spots of warmth: “We float on our backs, and the wind blows ripples across the water’s surface, and those ripples grow into waves that life us up and up.” She begins exploring the wonders of the beach, birds and shells and tide-rolls. “When the sun comes out, we sit on the rocks and watch the waves. Shine, shimmer. gleam, glow. It makes me dizzy to imagine where the sea ends. The ocean is so big that it makes every thought and worry I have shrink and scatter.”

As with all of Maclear’s books, complex ideas are presented through scenarios with which a young reader would be familiar. The effect is subtle—my daughter would not notice that she’s reading anything but a story about a girl who travels to the seaside. But she might notice that this is very different than other books about trips to the seaside. In a deceptively simple narrative package, Maclear is addressing issues of anxiety, of anger, of wonder, of emotions, of the power and knowledge that comes with growing and learning and changing one’s mind.

The girl learns to embrace the ocean, but with that comes a new anxiety. For how does one embrace an ocean after all? With something so huge, how do we wrap our arms around it? How do we love things that are much too big to hold? The girl comes up with scenarios involving putting the ocean in a bowl, carrying part of it home with her. But her wise older brother counsels her otherwise: “[he] says if I do that, the ocean will be less. He says the ocean may be big, but it isn’t endless.”

By the end of the vacation, the girl doesn’t want to go home—of course! Life itself being a tension between two pulls/poles. But she becomes reconciled with her departure by an awareness that the wildness of the ocean, its deep and dark mysteries and lack of containment, are most essential to what she loves about it. And that this same spirit and complexity she carries within herself: “Calm. Blue. Ruffled. Gray. Playful. Green. Mysterious. Black. Foggy. Silver. Roaring. White.”

Which means she’s not leaving it behind at all.