February 15, 2016

Good things come

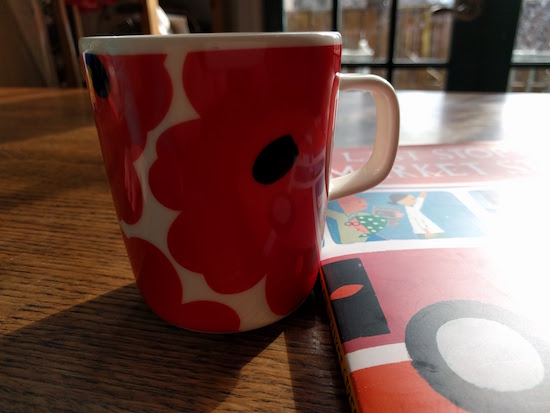

Sometimes the internet is portrayed as the opposite of the world proper, as the opposite of civility, and scapegoat for the end of all things ranging from bookshops to mail delivery, but my internet isn’t really like that. If it weren’t for the internet, I don’t know that I’d get much mail at all, and oh, I do get mail. Today, this most absolutely perfect object: a teacup! A gift from Jocelyn in Calgary whose manatea infusers delight me daily with her #TodaysTeacup photos. I am touched and delighted and overwhelmed, and so thrilled that this perfect object now has a home in my cupboard. happy! is exactly right.

(For me, Instagram is very much about happiness: I found a paragraph that articulated it exactly in The Republic of Love this weekend, even though Carol Shields wrote that book in the early 1990s, but then Carol Shields knew everything: “All morning there have been rain showers, but now a fan of sunlight cuts across the table and she stops to admire the effect. How fortunate a woman she is to possess this kind of skewed double vision. To be happy. And to see herself being happy.)

I do wonder if there is a direct correlation between happiness and being a person who gets a lot of mail. For me, the key is magazine subscriptions and ordering a lot of secondhand books, and being someone who regularly writes thank you notes and Christmas cards, thereby ensuring that I get a few of these in return. Yes, and also being publicly ebullient about the post in general, so that kind friends and strangers out there in online-land are inspired to reach out via the mailbox. After I wrote about Miss Rumphius last year, Theresa Kishkan mailed me a packet of lupine seeds. A few months ago, the write Jennifer Manuel sent me a beautiful card and a book by her late mother, Lynn Manuel, called The Lickity Split Princess, which I enjoyed reading with my family. I haven’t been in touch with my good friend Bronwyn for quite some time, although she sent me a lovely book called Ten Poems About Tea in the fall—and I sent the same book to my friend Melanie a while after that. I had a dream-come-true in December when my in-laws sent me a get-well cookie from The Biscuiteers (all the way across the ocean and everything!). I remember three years ago when I was very pregnant and also going through scary things like neck biopsies, the poet Gillian Wigmore mailed me a drawing of a unicorn her daughter had made. Recently we received an excellent package from our beloved Zsuzsi Gartner who’d heard about Harriet’s recent skating prowess and mailed her a copy of Hans Brinker, or the Silver Skates that had been lingering in a Free Little Library in her neighbourhood, and we look forward to reading it soon.

All of which is to say that I am very lucky, and perhaps kind of spoiled, but more importantly that people can be wonderful, and sometimes it’s true that good things come. The last line from Jane Gardam’s A Long Way From Verona: “But like at the Novelty Machine, I just felt filled with love, knowing that good things take place.” (I read that line back when I was in the midst of neck biopsy panic, and I remember the simple perfection of that sentiment, how it shifted my perspective. Plus, there were drawings of unicorns, which helped too.)

Today is the strangest day of all the others, the one holiday (Family Day here in Ontario, though it’s not celebrated across the country) upon which we also receive mail delivery. Mail delivery and a holiday: “the universe conspiring to delight me” I wrote today, and it’s true.

February 13, 2016

Happy Valentines Day

Everything’s been a special occasion around here lately, what with Pancake Tuesday and the fact that we had afternoon tea for dinner the day after that. And now it’s a long weekend, four days of it if you count Harriet’s PA Day, and we’re stretching out our Valentines Day celebrating and marking it with cheese. (Long weekend adventures have been extensively instagrammed.) It’s freezing cold outside but everything around here is wonderful and cozy, which feels nice after our terrible boring Christmas vacation rife with sickness. I just finished reading my second novel by Tana French (you MUST read Tana French) and now for sentimental reasons, am about to embark upon a reread of The Republic of Love.

February 12, 2016

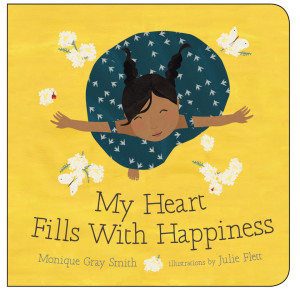

My Heart Fills With Happiness, by Monique Gray Smith and Julie Flett

As the world’s biggest fan of Little You, the board book by Richard Van Camp and Julie Flett, I’m particularly excited about Flett’s latest work, My Heart Fills With Happiness, a board book written by Monique Gray Smith (whose novel, Tilly, was winner of the 2014 Burt Prize for First Nations, Métis and Inuit Literature). “This book is dedicated to the former Indian Residential School students and their families—may you find what you seek,” reads Smith’s dedication, and her text is a celebration of First Nations culture as well as those perfect moments of exuberant joy that might be noted as ordinary if they weren’t so extraordinary (and perhaps the key to happiness lies in knowing that distinction): when you see the face of someone you love, smell bannock baking in the oven (with a teapot in the illustration; and oh, do I ever want to bake bannock now), when you’re dancing, singing, or holding the hand of someone you love. “What fills YOUR heart with happiness?” the book asks as it ends.

I received an advanced copy of My Heart Fills With Happiness back in December when I’d been ill in bed for weeks, and I recall reading it with Iris one afternoon while we were home alone together. It was late afternoon and the west-facing window in my room was poured through with sunlight, as yellow as this book’s beautiful cover. We were lying in my bed, face to face, and prompted by the book’s final question, we started talking about the things that fill our hearts: cake, and sunlight, and hugs, and books. The first proper conversation we’d ever had, it occurred to me, as her brain had undergone some transformation rather suddenly (she’d just turned two and a half) and now was (kind of) a creature capable of communicating complex ideas: she looked at me and said, “The sun makes my window so open.” And I knew exactly what she meant.

UPDATE: Bannock happened! We baked it this morning and the smell is indeed one that would fill your heart with happiness. Delicious. We happen to have leftover Devonshire cream in the fridge as well as strawberry jam, so my heart is basically exploding (and not just with cholesterol). I got the recipe from here.

UPDATE: Bannock happened! We baked it this morning and the smell is indeed one that would fill your heart with happiness. Delicious. We happen to have leftover Devonshire cream in the fridge as well as strawberry jam, so my heart is basically exploding (and not just with cholesterol). I got the recipe from here.

February 10, 2016

Frankie Styne and the Silver Man, by Kathy Page

My first proper job after graduating from university was temping as admin staff for a social services agency in the English Midlands, and it was a job that blew my mind in terms of what it taught me about the possibilities of narrative. My job required me type out reams of notes scrawled on yellow notepads and other paper scraps, and render these into a coherent story, and it was fascinating. I worked in Fostering and Adoption and wrote up family trees and histories for families pursuing these avenues, and then moved into Children and Families and supported social workers with overflowing caseloads working to protect vulnerable children and/from their parents (who were often unfathomably idiotic—or fathomably so; indeed, there was an entire basement room with paper files stacked to the ceiling of cases that stretched back generations).

My first proper job after graduating from university was temping as admin staff for a social services agency in the English Midlands, and it was a job that blew my mind in terms of what it taught me about the possibilities of narrative. My job required me type out reams of notes scrawled on yellow notepads and other paper scraps, and render these into a coherent story, and it was fascinating. I worked in Fostering and Adoption and wrote up family trees and histories for families pursuing these avenues, and then moved into Children and Families and supported social workers with overflowing caseloads working to protect vulnerable children and/from their parents (who were often unfathomably idiotic—or fathomably so; indeed, there was an entire basement room with paper files stacked to the ceiling of cases that stretched back generations).

I had this job concurrent to the Victoria Climbié murder inquiry, which delved into the systematic failure to protect a small girl who had been tortured and murdered by her guardians. The details of this failure are shocking, and yet they weren’t altogether: I’d seen how resources were scarce, how social workers were often impossibly tasked, and wondered too how far the social safety net would have to stretch in order to account for every possibility of unthinkable human evil. “The ends and edges of what [people] could have done or could do,” which is a line from Frankie Styne and the Silver Man, by Kathy Page.

Frankie Styne is a new edition of Page’s novel, first published in 1993, and it put me in mind of my favourite Hilary Mantel novels, her first two, Every Day is Mothers Day and Vacant Possession, dark comedies about the dark edges of humanity and their successful attempts to outmaneuver meddling social workers. Page’s social worker is Annie Purvis, who we know first from the point of view of her client, Liz Meredith, who’s just been moved into a terrace house with her baby. Liz has spent her time most recently living on a railcar after becoming estranged from her family, but since her baby’s birth (compounded by the fact that he has developmental abnormalities) she’s become tangled up in “the system”. Although she diverts all attempts to get her installed with a phone (living as she does by her grandmother’s advice to “Always avoid ties that bind”), she could do with a television, but in the meantime, she contents herself by listening to conversations between the troubled couple next door and imagining a different kind of reality existing on a planet far away, that life itself is merely the plot of a cheap pulp novel she’s somehow been stuck in.

A novel kind of like those penned by Frank Styne who lives next door to her, though they’ve barely met, and she’s never heard of his novels. Styne is a recluse, done in by a facial deformity and a lifelong struggle with sexual dysfunction, but now his latest book has been nominated for a major award and he’s going to have the press on his doorstep. Which drives him to become embroiled in a revenge plot of his own, sadistic fantasies that outdo any possibilities that have turned up so far in his books.

What impact do Frank Styne’s horror novels have upon the world? Is the impact more or less than the effect of Annie Purvis’s attempts to care for clients such as Liz Meredith and her son? Does Liz really require Annie Purvis’s meddling? And Page does such a terrific job of creating sympathy for each of her characters that we’re gunning for Liz, that we understand why she doesn’t take her son to a clinic after his foot is injured—because it’s true that they’d only take him away from her. And we know too that “they” is a group of people around a table, Annie Purvis and her associates, and they’re making their own gambles about the ends and edges of narrative possibility. That Annie Purvis has struggles of her own, a husband who resents the demands of her job. That all these people in close proximity affect each other in ways that no one can predict and that could never be plotted on a graph. That, contrary to Mrs. Thatcher’s assertion, there is such a thing as society after all, but what it is isn’t always pretty.

Frankie Styne and the Silver Man is dark and funny, painful and uplifting, marvellously satirical but never cynical, and thoroughly invested with good faith. Kathy Page is a marvel. This is the very best book that I’ve read in ages, and if I read another half as good in the next few months, that will constitute an extraordinary literary year.

February 8, 2016

The Disappearing Woman Writer

I’ve never read anything by Constance Beresford-Howe. Why not? Because her books were old, their covers not very enticing. That her focus was on older women also would not have meant anything to me for a very long time, would have been a drawback, actually (I’d had been through enough with The Stone Angel; I still don’t really love that book) though I recall that my mom had a copy of The Book of Eve. I never read her because her books were never assigned to me for a class, which the reason that I read many things. I suspect I didn’t read her books for the same reason that women proclaimed our universe “post-feminist” in the late 1990s. But her name was familiar when I encountered it in The Globe obits a couple of weeks ago. (You see, I am now at the point in my life at which older women have become interesting; I pore over the death notices every Saturday.) A name with which I am that familiar should perhaps have the death of its bearer meet with more press than just an obit: “Educator, Author, Lover of Literature.” The Globe’s Marsha Lederman had tweeted about her death, as well as had a few others who’d had her as a teacher at Ryerson. And I was glad when I learned that a longer obituary for Beresford-Howe was in the works. Because, see, I’d recently read the essay, “The Amazing Disappearing Women Writer”, and realized that lack of attention to Constance Beresford-Howe, in later life and in death, was not a literary anomaly.

I’ve never read anything by Constance Beresford-Howe. Why not? Because her books were old, their covers not very enticing. That her focus was on older women also would not have meant anything to me for a very long time, would have been a drawback, actually (I’d had been through enough with The Stone Angel; I still don’t really love that book) though I recall that my mom had a copy of The Book of Eve. I never read her because her books were never assigned to me for a class, which the reason that I read many things. I suspect I didn’t read her books for the same reason that women proclaimed our universe “post-feminist” in the late 1990s. But her name was familiar when I encountered it in The Globe obits a couple of weeks ago. (You see, I am now at the point in my life at which older women have become interesting; I pore over the death notices every Saturday.) A name with which I am that familiar should perhaps have the death of its bearer meet with more press than just an obit: “Educator, Author, Lover of Literature.” The Globe’s Marsha Lederman had tweeted about her death, as well as had a few others who’d had her as a teacher at Ryerson. And I was glad when I learned that a longer obituary for Beresford-Howe was in the works. Because, see, I’d recently read the essay, “The Amazing Disappearing Women Writer”, and realized that lack of attention to Constance Beresford-Howe, in later life and in death, was not a literary anomaly.

In her essay, Jeannine Hall Gailey asks the question: “So, how can the mid-life woman writer attempt not to disappear right before the eyes of prominent male writers, king-makers, editors, judges and juries of prizes and grants? How do we stay seen and heard when perhaps our youthful charms may be diminishing but our art may be improving?”

It was a question I came at as a reader, though I am a writer too with greying hair and a body that is slowly turning into a splendid pudding. But it was as a reader I considered it, how much we are missing. And it affirmed why I do what I do here and elsewhere, championing books from the platform I’ve made, making noise and shouting my darnedest to ensure that women writers don’t just disappear. And that I have to backtrack too, take note of all those books and readers who weren’t bright and shiny enough when I first encountered them, give them another chance.

I was so happy to read Judy Stoffman’s profile of Constance Beresford-Howe in the Globe this weekend, and to have it affirmed that she’s probably a writer I will deeply appreciate, with Barbara Pym comparisons as the cherry on the sundae. I went out on Saturday afternoon and picked up a second-hand copy of The Book of Eve, and look forward to tracking down her other books in time, and to doing a lot of shouting about them.

February 7, 2016

Patrin, by Theresa Kishkan

And so #TodaysTeacup continues, the Instagramming of my daily cup of tea, the end of the week marked with #CupAndSaucerFriday. I used to think I had too many sets of cups and saucers, but now it seems as though I don’t have enough. On Friday I took down the last of my cup and saucer sets to use, and was surprised to find that this one set is not from England—not Regency China, or Paragone Fine Bone China, or Coalport. No, this set was from a Czechoslovakian company called Altrohlau. Which was strange because I have Czechoslovakia on the brain, one of the settings for Theresa Kishkan’s beautiful, mysterious novella, Patrin—a novella in which the characters drink Earl Grey.

And so #TodaysTeacup continues, the Instagramming of my daily cup of tea, the end of the week marked with #CupAndSaucerFriday. I used to think I had too many sets of cups and saucers, but now it seems as though I don’t have enough. On Friday I took down the last of my cup and saucer sets to use, and was surprised to find that this one set is not from England—not Regency China, or Paragone Fine Bone China, or Coalport. No, this set was from a Czechoslovakian company called Altrohlau. Which was strange because I have Czechoslovakia on the brain, one of the settings for Theresa Kishkan’s beautiful, mysterious novella, Patrin—a novella in which the characters drink Earl Grey.

I first read Theresa Kishkan in her essay that won the Edna Staebler Personal Essay Contest, and which was included in her essay collection, Mnemonic: A Book of Trees. Unsurprisingly, trees factor prominently in Patrin as well, in patterns of leaves on a quilt inherited by the title character from her grandmother, a Roma from Czechoslovakia who’d immigrated to Canada and become estranged from the rest of her family. When her grandmother dies, Patrin tries to discern the quilt’s pattern, hoping they might provide clues to her family history, which is otherwise lost to her now, the answer to the questions: from where and what did I come?

I first read Theresa Kishkan in her essay that won the Edna Staebler Personal Essay Contest, and which was included in her essay collection, Mnemonic: A Book of Trees. Unsurprisingly, trees factor prominently in Patrin as well, in patterns of leaves on a quilt inherited by the title character from her grandmother, a Roma from Czechoslovakia who’d immigrated to Canada and become estranged from the rest of her family. When her grandmother dies, Patrin tries to discern the quilt’s pattern, hoping they might provide clues to her family history, which is otherwise lost to her now, the answer to the questions: from where and what did I come?

The novella weaves together several timelines from throughout the 1970s—Patrin embarking to Europe on her own and having her heart broken by a Gypsy musician; spending time with her grandmother in Edmonton after her father’s death, them sleeping together under the quilt; Patrin working in a bookstore in Victoria later in the decade, isolated from the world, trying to decode the mysteries of her own self; and Patrin journeying to Czechoslovakia to do exactly that in 1979, supposing the pattern of trees and leaves on her grandmother’s quilt might be a map of the area in Moravia in which her foremothers had lived and travelled almost a century before.

The world Patrin finds in Czechoslovakia is shadowy and mysterious, the elusiveness of Patrin’s own story underlined by Soviet-era suspicion and paranoia. A friend of a friend takes her on a journey to Moravia to find if her quilt-map line up with actual places after all, and if any history of her family remains. And here the story takes on dimensions of a fairy tale, rich and verdant with a touch of magic, with an ending that in retrospect was inevitable, and is also perfect.

There’s another teacup too—Patrin takes stock of her “batterie de cuisine” as she moves into her own apartment on Oak Bay Avenue in Victoria in 1974, including a mug “from a potter on West Saanich Road” with a ceramic frog at the bottom. We have a mug just like that, a #TodaysTeacup feature from a few weeks back, Patrin wending its own way into my world, surprising patterns emerging, real life as art’s echo.

There’s another teacup too—Patrin takes stock of her “batterie de cuisine” as she moves into her own apartment on Oak Bay Avenue in Victoria in 1974, including a mug “from a potter on West Saanich Road” with a ceramic frog at the bottom. We have a mug just like that, a #TodaysTeacup feature from a few weeks back, Patrin wending its own way into my world, surprising patterns emerging, real life as art’s echo.

February 5, 2016

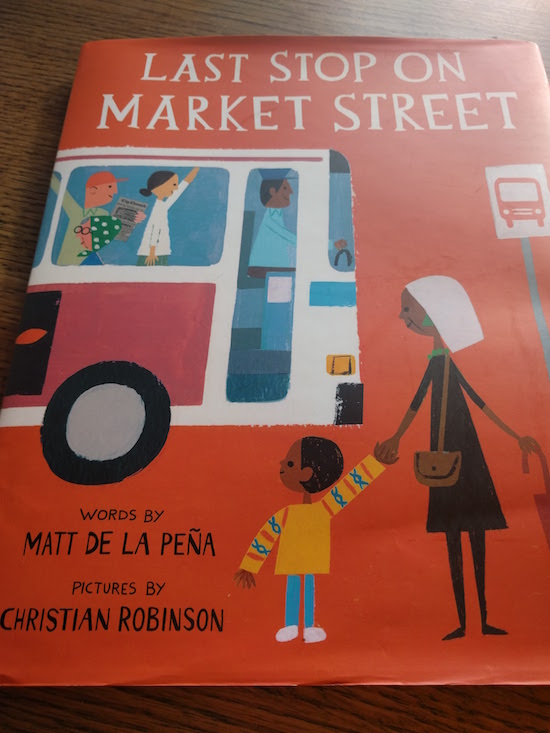

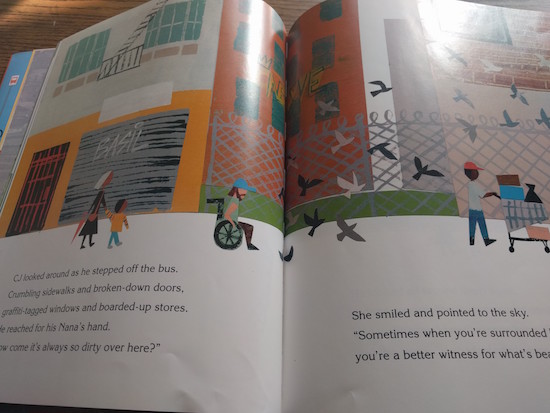

Last Stop on Market Street, by Matt de la Peña and Christian Robinson

I’ve been spending a lot of time lately thinking about the nature of an imperfect world, about the gifts inherent in that kind of reality. (The only kind of reality.) That accepting the imperfections and imperfectability of the world is not about giving up hope of making things better, but instead the reason why we mustn’t stop trying—where would we be if we did? And how other people keep us in check—even the assholes. Well-being lies not about improving the assholes, obliterating assholedom, but instead learning to live among them. Accepting too that everybody is someone else’s asshole sometime. It’s all a negotiation, this business of daily life in the world. Even negotiating with those people who will never understand that.

I read an article last weekend about a teacher remarking on her high-needs students: “There are a lot of kids here who keep life interesting.” I’m aspiring to maintain such a perspective on my fellow humans, the challenging ones.

A gift of living in the city and especially raising my children here is that the world’s imperfections are always close at hand. Garbage in the gutters, mentally ill people shouting obscenities in the streets, mentally sound people shouting obscenities in the streets, someone threw up on the sidewalk, drivers nearly bowling us over turning right on red lights, ugly graffiti sprayed on beautiful murals, and people who vape. Here is the world…and yet we love it anyway. Perhaps even more so. Because there’s also bees alighting on flowers, little kids holding their parents’ hands, squirrels eating sandwiches, cherry blossom springtimes, the wonder of an airplane soaring overhead, and music, and finger paint, and dancing to “Trouble” by Taylor Swift. It’s the same reasons we take to read Grimms’ fairy tales at their gruesomest: because here is the world…and yet.

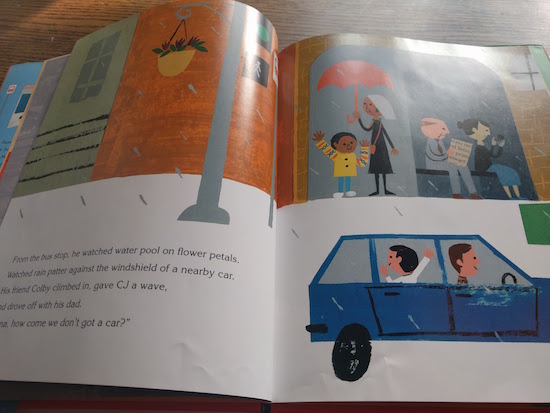

The city in Matt de la Peña and Christian Robinson’s Newbery Award-winning Last Stop on Market Street is San Francisco which, by virtue of its density, is a city of contrasts. We see this as CJ and his Nana board the bus on Sunday after church and make their way across town for a weekly appointment. CJ wonders why they have to go. He wonders why they can’t travel by car, like their friends who passed while they were waiting at the bus stop. But his Nana reminds him of the advantages of riding “a bus that breathes fire” (there is a dragon on the advertisement on the bus’s side), and of the people they’ll meet, the stories CJ will encounter on his way.

She’s proven right too, CJ’s Nana, knitting as they go, making friends with the man with the seeing-eye dog, convincing the man with guitar to break out in song—to which CJ closes his eyes and launches into a reverie, all butterflies and rhythm and moonlight. When the song ends, CJ tosses a coin into the man’s hat and suddenly they’re at their destination: “Last stop on Market Street!”

CJ is still not sure as he steps off the bus, taking his Nana’s hand. It’s a rough neighbourhood with boarded up shops and graffiti. The only birds are pigeons. His Nana points to the sky though: “Sometimes when you’re surrounded by dirt, CJ, you’re a better witness for what’s beautiful.” And in the following spread we see a bigger picture, a rainbow overhead. “He looked all around them again,/ at the bus rounding the corner out of sight/ and the broken streetlamps still lit up bright/ and the stray-cat shadows moving across the wall.”

The subtle rhyme of de la Peña’s prose gives the story a kind of music, rhythm and cadence. The journey culminates with CJ and his nana’s arrival at the soup kitchen where they work every week serving lunch to the people of the neighbourhood. People who are people in their own right: Esther with her new hat, and the Sunglass Man. And CJ tells his grandmother that he’s glad they came.

The story concludes with CJ and his nana back waiting for the bus, with caged spindly trees and overflowing litter bins, but the beauty’s there: we see it now. Perhaps it’s been there all along.

February 1, 2016

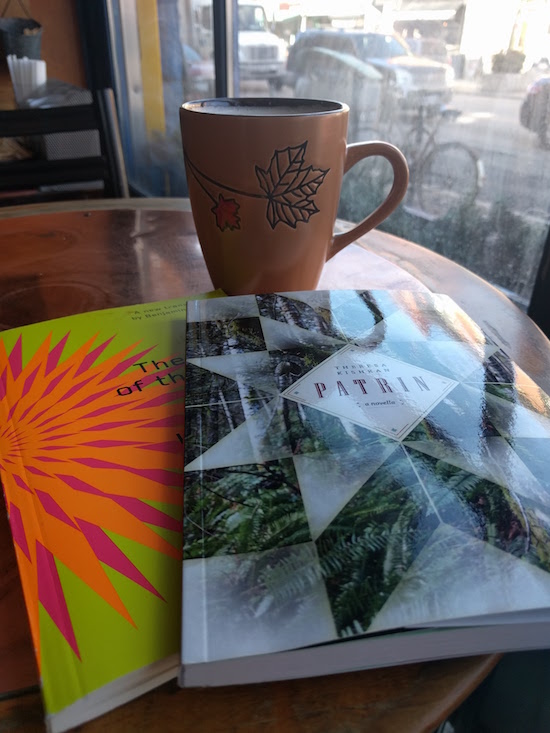

Gifts to Myself

This morning was a gift to myself, a handing-in-your novel gift, though it didn’t occur to me that this was the occasion until I was looking for an excuse to spend my free time sitting reading a book while drinking a chai latte in a cafe. By this point I’d had my hair cut and my eyebrows waxed, and finally dropped off my new bathing suit to have the straps shortened—all the errands that I’ve been putting off for ages. I ordered a new green bin to replace our battered one, and bought clear garbage bags at the hardware store to use for green waste until the new bin arrives. Bought some stamps and finally mailed the thank-you notes that I’d had Harriet painstakingly write after Christmas, and which have waiting ever since to be enveloped and addressed. And yes, still had time to kill before it was time to fetch Iris from school, and so I sat in Future Bakery finishing The Hour of the Star, by Clarice Lispector. Thinking about the time I’d been there about two years ago reading Last Friends, by Jane Gardam, also having just had my hair cut and brows waxed—grooming, for me, is pretty much an annual affair; I’m low maintenance, or perhaps “slovenly” is more apt—and how Iris had just been a baby then and getting out for time to myself had been a major accomplishment. This time it’s an accomplishment of a different kind—I’ve been working hard this last two weeks on edits of my book, and also contributing to the wondrousness that is 49th Shelf at the moment (and I’m particularly proud of what we’re continuing to do there). It was such a pleasure to sit and read, and also to get those errands done. I’m mostly very reluctant to waste my child-free time on such things, but then I don’t really want to waste our Saturday/Sunday family time on them either, so then thank-you notes, for example, end up sitting unsent for weeks and weeks. Once in a while it’s nice to clear the decks. A gift indeed.

Though of course gifts to myself are hardly few and far between. I am nothing if not generous in that respect. Yesterday I had another excellent morning, following Harriet’s swimming lesson as we all headed to Kensington Market to buy chicken for last night’s dinner and also to try churros for the first time, and get wood-fired bagels for lunch, and I got to browse at Good Egg. Where I bought a beautiful Marimekko mug, my favourite print, the first such mug I’ve bought since #TodaysTeacup started, and yes, let’s not go overboard, but how wonderful to just want a thing…and simply have it. It’s almost more precious just for that, and I’m very pleased about this impulse buy. Also that it included the Newbery Medal-winning Last Stop on Market Street, which is so wonderful and I look forward to writing about this week for Picture Book Friday. So you see, not all my indulgences have to do with mugs and teacups—only most of them.

January 31, 2016

Bearskin Diary, by Carol Daniels

Carol Daniels’ first novel, Bearskin Diary, is driven by a remarkable protagonist, powered by compelling narrative voice and an extraordinary point of view. Sandy Pelly was part of the “Sixties Scoop”, a First Nations child taken from her parents and set adrift in the fostering and adoption system. Her story, unlike so many others, turned out mostly well—she was adopted by white parents who were loving and supportive, who did their best to fight against the racism omnipresent in the society in which they lived, and she was well loved by her grandmother, her Ukrainian “Baba“, who instilled in Sandy a sense of her own self-worth and an instinct for story-telling. But the loss of her heritage and culture is deeply traumatic, a loss whose effects Sandy can’t even articulate properly—she doesn’t know what she’s missing. But she knows she’s missing something, not least of all a place where she belongs. There is a disturbing remembrance of Sandy at five-years-old trying to scrub away the brown from her skin.

Carol Daniels’ first novel, Bearskin Diary, is driven by a remarkable protagonist, powered by compelling narrative voice and an extraordinary point of view. Sandy Pelly was part of the “Sixties Scoop”, a First Nations child taken from her parents and set adrift in the fostering and adoption system. Her story, unlike so many others, turned out mostly well—she was adopted by white parents who were loving and supportive, who did their best to fight against the racism omnipresent in the society in which they lived, and she was well loved by her grandmother, her Ukrainian “Baba“, who instilled in Sandy a sense of her own self-worth and an instinct for story-telling. But the loss of her heritage and culture is deeply traumatic, a loss whose effects Sandy can’t even articulate properly—she doesn’t know what she’s missing. But she knows she’s missing something, not least of all a place where she belongs. There is a disturbing remembrance of Sandy at five-years-old trying to scrub away the brown from her skin.

Things are going well for Sandy. Against the odds, she’s making it as a TV reporter, a rare position for a First Nations woman in the 1980s (and not so common these days either)—and we’re shown the racism she has to contend with from co-workers. She and her best friend Ellen enjoy regular Girls Nights, and it’s at one of these that she meets Blue for the first time. A Metis police trainee, she is instantly attracted to him, for obvious reasons, but also because she sees a glimpse in him of what she’s missing in herself. Blue is similarly alienated from his culture, however, and their relationship proves complicated—she throws caution to the wind and decides to follow him to Saskatoon, where he lives and works, but after a period of domestic bliss, she realizes he’s still distracted by a previous relationship that might not be as far back in the past as she’d been lead to believe. While this revelation is devastating, however, Sandy has other preoccupations—she’s managed to find a great job in her new city, and has just received a troubling tip about Saskatoon police officers taking First Nations women into isolated areas and raping them, getting away with it over and over again. And as she’s grappling with just how to tell that particular story, Sandy is also connecting with local First Nations Elders and discovering the richness of a culture that’s been denied to her for her entire life.

I read the book in a couple of days, and found it fast-paced and really absorbing. Although I was compelled by the story itself and its main character, more so than the novel’s structure, the container that held it. While Sandy was a rich and textured character, secondary characters were more one-dimensional. There were also strange shifts in point-of-view throughout the text. But it also occurs to me that critiquing the book by English literature standards is also beside the point—Bearskin Diary is part of a different tradition and has a more mythological structure, with expansiveness instead of depth, with depth in the places that I didn’t look for it at first. It’s chronology too is remarkable, the present moment dissolving into the past—each one containing all those that came before. It’s a novel with the feel of the oral tradition—and indeed it’s the voice that draws the reader in.

Which makes reading Bearskin Diary really a pleasure. In a time in which it’s never been more important that First Nations’ women voices are heard (and read), Daniels’ novel is definitely one not to miss.

January 29, 2016

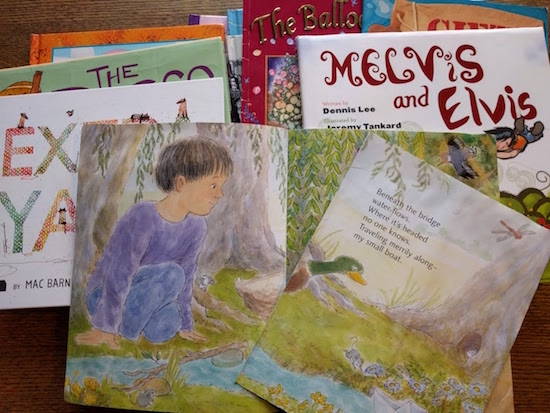

Picture Books We’ve Loved to Pieces

Wednesday was Family Literacy Day, and on 49thShelf, I wrote about the picture books our family has read to pieces. Reading with my children was been one of the most incredible parts of my life since they were born, and we’ve all come a long way since the first time I observed Family Literacy Day (which was six years ago, and I turned it into a week-long blogging extravaganza. Scroll down a bit here to se what we got up to). These days Harriet reads by herself more often than we read together, but we still read picture books every night, plus some of a chapter book—at the moment we’re doing The Borrowers Afield and it’s so perfect. Hanging out with books is my favourite way to be a family—or to be anything, for that matter…