March 9, 2016

Barbados in Words, Part II

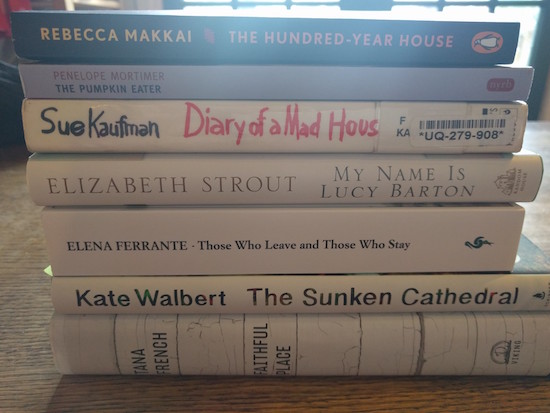

I think photos say it better though. Mostly because we really didn’t do much—you’ll notice that I took very few photos that weren’t from the vantage point of a beach lounger. By the end, we were getting bored (and sick of eating), which was kind of the point. To be bored—what a luxury. Also, to read an entire book every single day. But really, speaking of luxury, best of all was the time together, just the two of us. We haven’t spent a week without our children ever since they were born, and we’ve never been to an all-inclusive resort, or to the Caribbean. The closest we’ve ever come to a beach vacation was our time in Northern Thailand building a house for Habitat for Humanity, which had no beach and involved mixing cement by hand and brick-laying (which, incidentally, I’m not very good at, in case you were wondering). So this trip to Barbados was precedent setting. And probably mostly once in a lifetime. But how cool that that happened last week.

Our tenth anniversary was last June, and we might have gone away then except that Iris was too small and we wanted to go to England before she turned two (and therefore required a seat purchase). So it was put off until this year, which was fine because how nice to be still celebrating our anniversary nine months later. And none of it could happened without my wonderful mom who came and took excellent care of our daughters so that we didn’t worry about them ever, ever. (“Was it difficult to adjust to being away without then?””Well…no.”) And so we two had a week in paradise where the weather was always always perfect, where nobody had to cook or make school lunches, and we could sit with just us at the table—except for the time our breakfast was interrupted by a monkey.

In Barbados, there are trees on the beach, which didn’t prevent me from breaking out in a terribly rash from my sun allergy, but I didn’t care because I was sitting under a tree on the beach. Where the water was so magically blue, and I was either reading or swimming, and the sea was so warm and we floated in the saltwater with incredible ease—nothing has ever been more relaxing. Sometimes, to break up the day, we sat upright, but not very often. We drank rum punch, pina coladas, and daiquiris before lunchtime. I ate friend plantains for breakfast every day until I was tired of them. Our beach was a five minute walk from the town of Speightstown, which gave us a glimpse of a Barbados a little more real than our resort afforded, and also the most amazing bakery and sea views at the Fisherman’s Pub. And there were so many hours in the day, it seemed unfathomable. To read an entire book, and still have a few hours free? What an amazing indulgence. Every day the sun went down around 6pm and we made a point of marking the occasion…with another drink.

March 8, 2016

In Time of Need, by Shakirah Bourne

( Or, the alternate blog post title: “Barbados in Words Part I” )

Or, the alternate blog post title: “Barbados in Words Part I” )

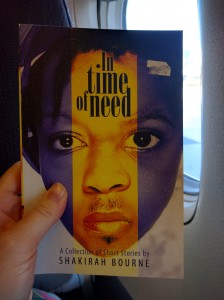

In the future whenever I think about the challenges of fostering a thriving literary culture in a country like Canada (pop. 35 million—as opposed to the US’s 318 million) I’m going to think about the population of Barbados, which is 285,000. Literacy rates are sky-high in Barbados, but there aren’t many bookshops outside the capital city of Bridgetown, which made our vacation last week particularly unique in our experience—this trip was just five minutes away from being the only one we’ve ever taken that did not involve bookshop pilgrimages, and from which we’d come home with fewer books than we’d left with.

Except…that after finally making our way through airport security, five minutes past when our boarding time had started, a bookshop appeared before us at the Grantley Adams International Airport, like a vision. A terrible husband would have suggested that instead we get on the plane, but my husband knew better, and so into the shop we went, me in pursuit of a single thing: a literary book by a Barbadian writer who was a woman. And there is was, In Time of Need, by Shakirah Bourne, a self-published title I knew nothing about, and after all, time was a-wasting, so bought it and rushed for the plane. And I happily read In Time of Need all the way home.

It’s a collection of stories, many of which have already appeared in Caribbean literary journals (including Arts Etc Barbados, which is edited by Bajan-Canadian Robert Edison Sandiford), and which was awarded the Barbados Governor General’s Award for Literary Excellence last year. The opening story, “Getting Marry,” is from the perspective of a young boy confused by his parents’ decision to become married (“because I could have swear that them was married every since”) who decides that getting married is all about kissing and cake, and decides to get in on the action himself with a young friend, only to witness a very adult moment from his hiding spot under the cake-lady’s table. The story is fixed in the boy’s point of view and rich with the slang and colloquialism of his language, but then the voice we encounter in the next story is entirely different (from the pov of a young woman who’s just been sold into sex trade, though she doesn’t realize it), and still the next, “The Last Crustacean,” which is narrated by a crab—all of which is to say that this is a fast-paced eclectic collection, a veritable grab-bag of good stories.

I loved “Sheep Don’t Stand Still,” with its fabulous twist, about a woman who thought she was living How Stella Got Her Groove Back with a Bajan lover she’d met on the beach, but who finds out more than she bargained for when he dies suddenly and she goes back to Barbados for the funeral. “If Dogs Could Talk” is a terrific story, one-sided dialogue by a woman being interrogated by police after her cousin is accused of murder. “Four Angry Men” is about politics and takes place over an afternoon at a rum shop. These are stories about domestic violence, child abuse, and family ties. “I Didn’t Know” has the most wonderful opening paragraph: “I first met Betty when her son stole my car. As I watched her punch him in the face and force my car keys from his pocket, all the while begging God for forgiveness, I decided we should be friends.” Another stellar selection was “The Five Day Death of Mr. Mayers,” a story of happenstance and misunderstanding, one thing leading to another with hilarious results. And I loved “A Tear for Miss Cinty,” about a young girl who doesn’t appreciate her mother’s devotion to an elderly neighbour until her own mother is old herself, and left so much alone.

This was all certainly a side of Barbados I was not privy to from the vantage point of my all-inclusive deck chair, but the colours, the sun, the flowers, the food, the slang and rhythms had become familiar to me and immersion in Bourne’s literary worlds was the perfect way to make my vacation last a little bit longer. So nice to bring a little piece of that place home.

February 26, 2016

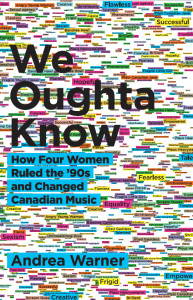

We Oughta Know, by Andrea Warner

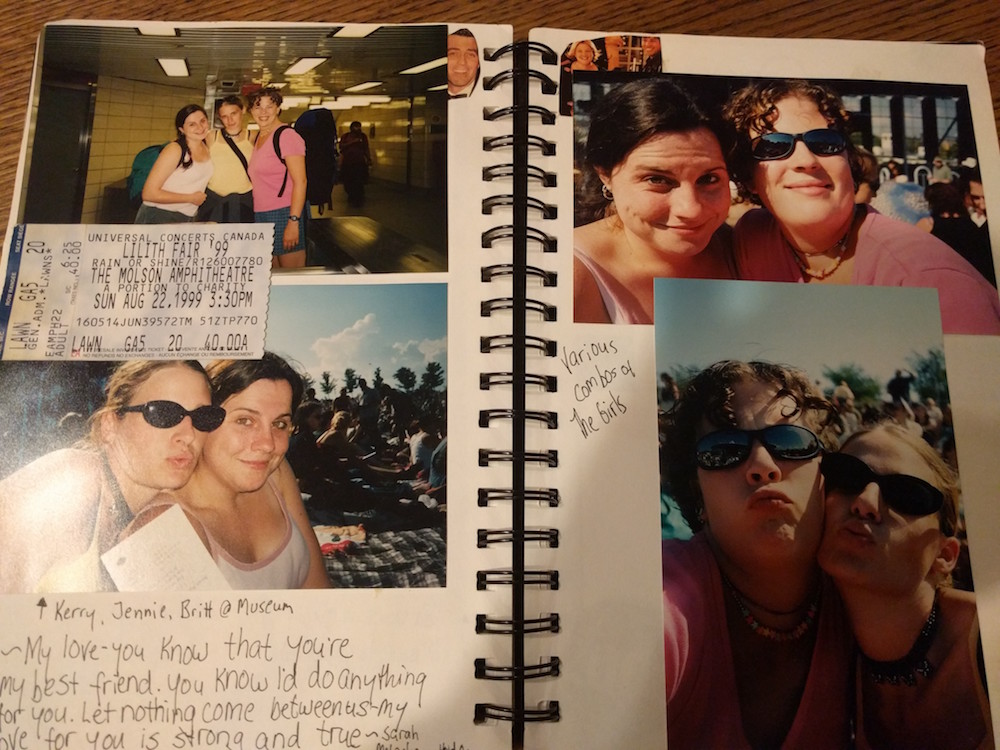

The very first real concert I went to (i.e. not with my dad) was to see Sarah McLachlan on tour for Fumbling Toward Ecstasy, a CD I’d recently purchased from Columbia House for a penny. This was in grade nine, I think, 1993 or 1994, with my best friends Britt and Jennie. Britt’s dad drove us there, to the theatre in Lindsay, ON, where we were part of the amazing, intimate performance, and I saw a girl with dreadlocks who kind of looked like a boy, which left me flummoxed. There is a connection, I think, between having seen Sarah McLachlan, powerful and awesome at her piano, on the guitar, and that Britt and I would spend all of high school performing at talent shows and low-rent concerts playing pop covers on our acoustic guitars, singing in harmony. We really took it for granted, all those amazing women who articulated our feelings so well, whose lyrics we scrawled in our scrapbooks. It was the times we were living in. It seemed inevitable that we’d see Sarah McLachlan against six years later at a much larger venue, us sitting high up and far away on the grass, watching her perform with Sheryl Crow, Deborah Cox. I think the Dixie Chicks were there. Biff Naked on a side stage. Women in songs were in the ascendence. “Women in Songs” was the name of a popular CD series here in Canada in the last few years of the decade, and that the collections were feminist or even that these were women at all seemed to use kind of incidental as we drove down the main street in our town singing along with Natalie Imbruglia as she bared her heart with “Torn.”

In her book, We Oughta Know: How Four Women Ruled the ’90s and Changed Canadian Music, Andrea Warner articulates that whole scene, and the remarkable fact that four Canadian women were leading the charge of women in song: Celine Dion, Sarah McLachlan, Shania Twain, and Alanis Morissette. These four women too are (along with Diana Krall) are the only Canadians on Canada’s best-selling artists lists, coming in above the Beatles. And even more remarkably, they all made their mark during a five year period in the mid-1990s. What was going on exactly, Warner wonders? How did they do it?

In her book, We Oughta Know: How Four Women Ruled the ’90s and Changed Canadian Music, Andrea Warner articulates that whole scene, and the remarkable fact that four Canadian women were leading the charge of women in song: Celine Dion, Sarah McLachlan, Shania Twain, and Alanis Morissette. These four women too are (along with Diana Krall) are the only Canadians on Canada’s best-selling artists lists, coming in above the Beatles. And even more remarkably, they all made their mark during a five year period in the mid-1990s. What was going on exactly, Warner wonders? How did they do it?

Dion, McLachlan, Twain and Morrisette are not musicians usually linked together, more often viewed in terms of their differences—the good girls and the bad ones, the authentic musicians versus the manufactured ones. Warner makes the interesting point that as a teenager, she regarded these women as she regarded the members of The Babysitters Club, definitive types, not allowing for complexity of character. Making assumptions: how could Dion with her entrepreneurial skills be a Feminist with all her love schlock, and the same with Twain and her bared midriffs? Exhibiting the same narrow-mindedness that led critics to be baffled by Morissette’s “Jagged Little Pill” (which, incidentally, was the only album my husband and I ended up with two copies of when our CD collections merged):

‘The sweetness of “Head Over Feet,” the sensitive sprawl of “Mary Jane,” and the quirky landscape of “Ironic” were baffling to the easily confused, particularly to those who were committed to painting Morissette as a screaming, seething ball of rage. How can she be angry but so gentle here? Well, how can you have both a right hand and a left hand? It’s simple, provided you’re not someone who hates women. People contain multitudes and women are people; therefore women contain multitudes.’

In her book, Warner takes us track by track through the albums that rocketed these women to stardom, and also examines her own feelings toward them and how coming to admire Dion and Twain for their talent and hard work is a part of her coming to terms with her own notions of feminism. She also takes inspiration from 90s music heroines and blends the personal in with her cultural analysis, discussing how her parents’ separation and own ideas of love and marriage influenced her perspective on Dion’s music, or how McLachlan’s devastating Rarities, B-Sides and Other Stuff (which I always used to put on when I was at my most angst-full, just to feed the pain) intersects with her grief around her father’s death. She also examines how these four women were regarded by the music industry, by the media, the sexism and stereotypes and the system that is set up so that women are unable to succeed, for example, the rule against playing two songs by women in a row on the radio, which is what galvanized Sarah McLachlan to start The Lilith Fair to show that women aren’t merely to be pitted against each other, but can stand together. Fascinating too to consider the stupid Lilith Fair backlash, that it was reverse sexism. I remember being gibed about “lesbians” by certain morons in my company at the time who knew I was going to the concert, as though most rock festivals are not enormous cockfests (which are distinct from “enormous-cock fests”) and why don’t we ever talk about that?

Warner is a music critic for CBC Music and Exclaim, and a warm, engaging writer who celebrates the power of girls and women and their voices, and critiques the culture that made all this happen. An appendix in We Oughta Know includes a long list of other Canadian female acts who made their mark throughout the 1990s—Alannah Myles, Amanda Marshall, Jann Arden, and others—making clear that the four women spotlighted in her book are not merely some freak phenomena.

“The ’90s were a remarkable decade for girls like me, and ultimately, the woman we would become. When you come of age in a time when women have voices, take up space, are visible creators and entrepreneurs, it never dawns on you that silence is the rule and these women, your idols, are the exception.”

February 25, 2016

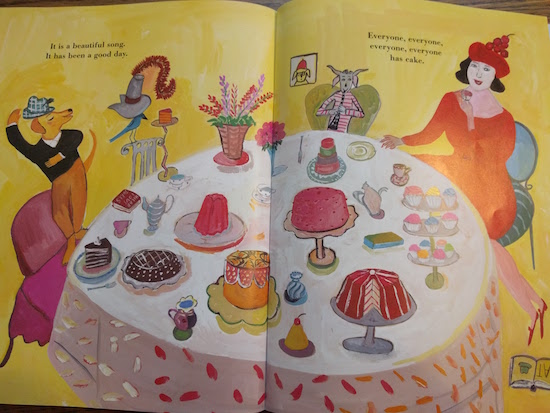

13 Words, by Lemony Snicket and Maira Kalman

I came to Maira Kalman by accident, which seems particularly Maira Kalman-esque, really. And now I am in love with her work, the themes and ideas she returns to again and again. I bought her picture book alphabet, Ah-Ha to Zig-Zag for my children (yeah, right, no, for me), and was overjoyed to find 13 Words, written by Lemony Snicket, in the library not so long. And loved that one so much that I had to buy it too.

I don’t know Lemony Snicket from A Series of Unfortunate Events as Harriet is averse to literary peril, but we are mystified by and simultaneously in love with 29 Myths On the Swinster Pharmacy. And then there is his picture book with Jon Klassen, The Dark. He promises weird and wonderful, and totally delivers.

From Publishers Weekly: “Based on an unlucky number of key words and authored by someone who takes pleasure in unfortunate events, this volume conjures a sense of foreboding.”

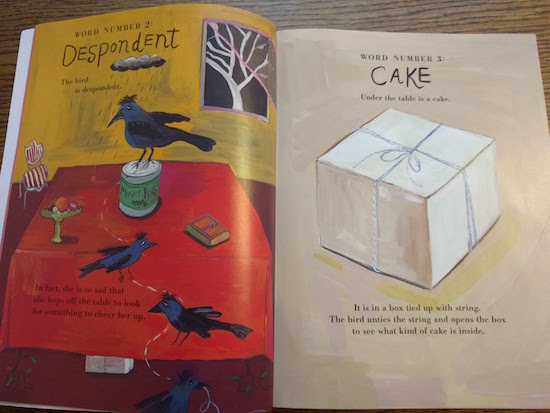

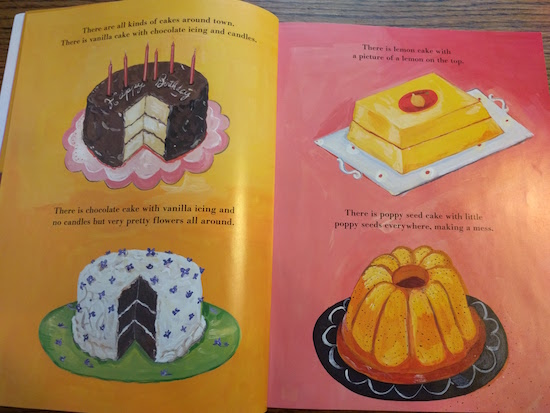

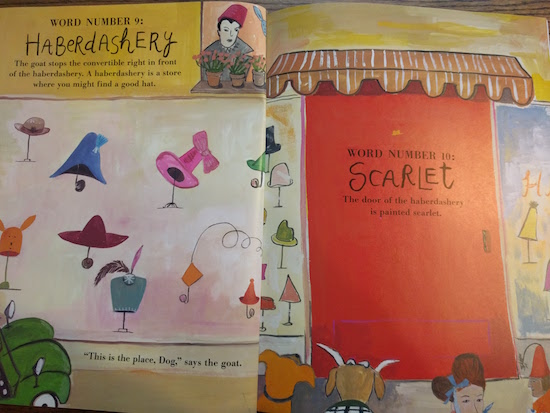

The premise is 13 seemingly random words and a story created around them. And this is not your usual word book. While there is “Bird,” “Baby,” and “Hat,” there is also “Despondent,” “Haberdashery,” and “Panache.” And yes, there is cake. Is there ever cake—even one of the bundt variety.

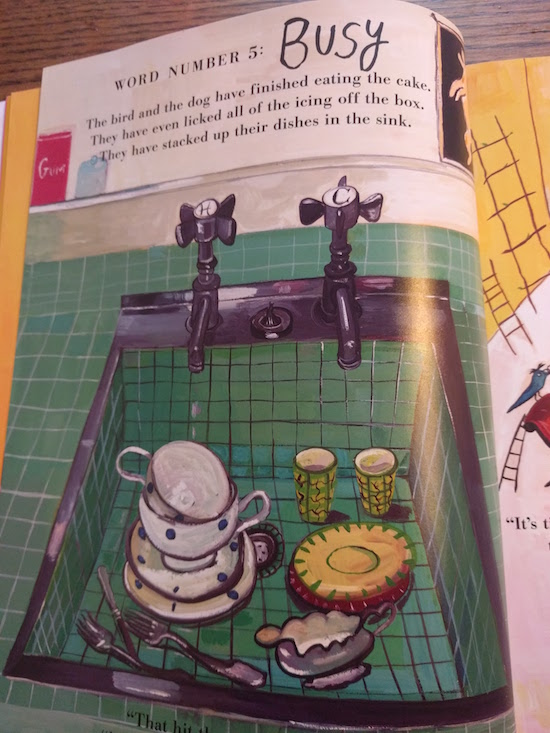

One thing leads to another, but to never quite what you think. There is a goat in a convertible and the bird starts painting ladders, and there are dishes in the sink.

Kaman’s illustrations are so perfect here, every ordinary thing a revelation, full of magic, so that it doesn’t seem so strange to see, say, a giraffe behind the wheel of a car, a table sprouting vines, and or a baby minding a hat shop.

It doesn’t make sense, but the best things rarely do. And like all the best things, it ends with a party (with cake!) and a song.

Although even so, the bird is still despondent.

February 23, 2016

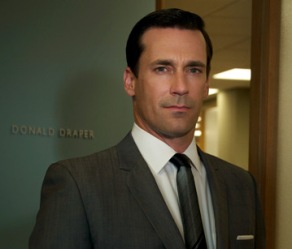

What is Don Draper thinking?

“ Draper. Who knows anything about that guy? He could be Batman.” —Harry Crane

Draper. Who knows anything about that guy? He could be Batman.” —Harry Crane

“What is Don Draper thinking?” —frequent jotting in my notebook during my rewatch of Mad Men Seasons 1-3

The first time I watched Mad Men, it confused me, and the reason I’ve just rewatched the first three seasons for (perhaps?) the fourth time is that it still does, which is precisely the point. I didn’t realize then. That the very thing that compels me to the show is that so much of it and its characters remain a mystery, some of which becomes clearer as I watch it again (and again) but some of it doesn’t.

I don’t get Don Draper, but then nobody does. Inconsistency is his salient feature, that a man whose treatment of women is shameful admonishes others about being respectful to them (and his other respectful bents too, men taking off their hats in the elevator etc.), although he’s really kind of horrible to everybody. One thing I do know about him is that he gives terrible advice, and that’s why I loved the final episode of the series, where he delivers one of his sermons to Stephanie, who doesn’t buy it and thinks it’s bullshit and tells him so—that’s a huge moment, I think. His pitches and his advice are all the same, and their power is his delivery, which might convince you that it almost means something. But I’m starting to think it never does.

I am forever married to the idea of Don and Betty, and I can’t shake it. In the final episode, there is a connection between them, though I don’t think it emerges until they split. (Remember what she says when he sleeps with her while he is married to Megan? That line [paraphrased] about the worst way to get close to Don is to love him? When Betty stops doing so, she starts to really mean something to him as a person in her own right.) My insistence on their substance as a couple mostly stems from about twelve seconds in the episode “The Wheel” in which his pitch for Kodak’s Carousel is so good that he buys it himself, and comes home believing that he loves his family. We see him meet him at the door—he’s coming for Thanksgiving after all. He’s done the right thing. But then it all dissolves and we realize it was a fantasy (or a nightmare), and that his house is empty. He sits down on the step while “Don’t Think Twice It’s Alright” plays, and here is where I wrote, “What is Don Draper thinking?” I used to think he was regretting mistakes he’d made, that he wasn’t a better husband and father, but now I’m not so sure.

I am forever married to the idea of Don and Betty, and I can’t shake it. In the final episode, there is a connection between them, though I don’t think it emerges until they split. (Remember what she says when he sleeps with her while he is married to Megan? That line [paraphrased] about the worst way to get close to Don is to love him? When Betty stops doing so, she starts to really mean something to him as a person in her own right.) My insistence on their substance as a couple mostly stems from about twelve seconds in the episode “The Wheel” in which his pitch for Kodak’s Carousel is so good that he buys it himself, and comes home believing that he loves his family. We see him meet him at the door—he’s coming for Thanksgiving after all. He’s done the right thing. But then it all dissolves and we realize it was a fantasy (or a nightmare), and that his house is empty. He sits down on the step while “Don’t Think Twice It’s Alright” plays, and here is where I wrote, “What is Don Draper thinking?” I used to think he was regretting mistakes he’d made, that he wasn’t a better husband and father, but now I’m not so sure.

“It shouldn’t have happened,” Don tells Rachel Mencken during the first season, and it seems like he’s referencing his feelings toward her with the “it”, but now I’m thinking that he’s talking about his marriage. Later Betty alludes to the fact that their marriage came about suddenly—they got engaged quickly and then she got pregnant, or perhaps it was the other way around, and that was the end of their New York life. The details of everyone’s life pre 1960 are quite hazy on the show, which is strange because it’s so pointed about so many details. But for so many of these characters, you get the sense that they didn’t exist before the cameras started rolling. An example: in their entire friendship, Betty never once tells Francine that she used to model until that one episode where Francine comes over to borrow a dress? There are others like this, scenes between Don and Roger when it is hard what they’ve meant to each other, and the haziness is underlined by the weird flashbacks, dopey early Don who seems so different that the surefooted Don we know in the present (although he isn’t really—he’s just better at playing the part). There is a flashback of Don in California, goo-goo eyed about a girl he met called Betty, and it seems false to me. Similar to one that comes later in the series when we see how he hoodwinks Roger into giving him a job, though this isn’t consistent with the story that Roger tells, and Don just doesn’t seem like Don in any of these scene. But who is Don, anyway? And are his flashbacks as made-up as his pitches?

(“Who ARE you? is a question that characters ask each other throughout the series, in all manner of tones.)

So the revelation to me was that Don and Betty might have never meant anything together at all, that the Don’t Think Twice… moment wasn’t meaningful, and even if it was, that’s just twelve seconds of meaning. Plus remember later when Don tells Megan that he didn’t love his children…until he did (and I think he does, but who knows?) but when did that start? Though I think Betty does love him when the series starts, or at least the idea of him, or at least she wants to have sex with him, but he doesn’t even give her that. (Season One is very much about notions of wanting and desire, in both the consumer and the carnal senses.) “All this,” is the thing they talk about, usually with a hand gesture toward their lurid green headboard or their plaid kitchen walls. What “this” is is never clearly delineated—it seems to very much be the house and its contents (“What do you put in that freezer I bought you?” Don asks her), which is strange because neither of them really likes the house. To Betty, the house is a prison, and to Don it is an anchor of the worst kind. He longs for freedom, a lesson he learned from the hobo who told him, “Home, mortgage, a family—I couldn’t sleep. Went on the road with the clothes on my back, and now I sleep like a stone.” The trouble is that he also wants power and status, and these things come with baggage. And without the wife and house, he doesn’t have the power or the status. He needs Betty, even if he doesn’t want her.

The only proper, reciprocated connection between them, I realized, was in the third season when Don is contemplating moving up the ranks at PPL and being moved to London. He tells Betty about this, and she’s thrilled with the possibility of getting out of the suburbs, and you see that they’re good when making plans like this (and here they’re at their most Revolutionary Road-ish). It’s the ordinary they have more trouble with, the role-playing they’re really poor at, whereas their scene in Rome, when they’re both pretending to be people they aren’t, they’re amazing. The trouble is, however, that Betty knows who she is and when she’s posturing, but for Don Draper, there isn’t any difference.

I thought a lot about Pete Campbell this time, with more sympathy than I had before. I’ve always found him loathsome, and he is, but I see now that he’s not simply a foil to Don, he’s also having parallel experiences. And that he’s much more foregrounded in the show than I ever thought he was—the show begins with his marriage to Trudy and indeed they’re the only couple that stays together throughout (and I always think of Sarah’s comment now: “people who dance that well together, in such a very ambitious way, should never have parted”). Trudy is wonderful, and while Pete is loathsome, their marriage is such a partnership in a way that Don and Betty’s never is, or Don and Megan’s either. (Trudy was not a virgin when she got married—remember? She lost her virginity to the publishing guy who offers to sell Pete’s story in Boy’s Own Magazine. I think this is signifiant.) Trudy knows what she’s doing throughout, and she is the one character who really does get what she wants. Though the idea that this is somehow emasculates Pete and the show’s preoccupation with their power dynamic, and how powerful women are emotionally trying for men is one thing I find really tiresome…

Peggy too is one of the show’s anchors—the pilot is her first day of work and she develops in a way that none of the others do as the series progresses. She is also a version of Don, assembling her persona from what she sees of others just as he does, and I think we understand Don better because of Peggy’s openness with this. She is always watching, watching, while Joan is always being watched, and for each woman, this is her path to power, each one using this, respectively. But here’s another thing I got wrong the first time, another thing that confused me—Joan and Peggy throughout the series, the two paths for women to success. And I was thrown off by the ways in which they were alike and different, and none of it was entirely congruous—where is the symmetry. But no, I realized, as I watched the first three seasons this time. These are not THE two paths for women, but simply two paths, and they aren’t parallel or in opposition, but they’re both different, and each one gets each woman to where she wants to go. This is huge, I think. Peggy and Joan aren’t defined in relation to men or even to each other, but as individual people. It’s a hard thing to get one’s head around.

But a lot of things are: this is deliberate. And it happens because of the bizarre surrealness that permeates so many scenes of the show, the moments that have no footing in reality except to make viewers cringe: Sally Draper driving, Peggy stroking Don’s hand, Glen watching Betty pee, when Lois drives a lawnmower over that guy’s foot. Our reactions are visceral and sometimes the scenes are inexplicable, and all of it keeps us as viewers from getting complacent.

February 22, 2016

There will be cake—eventually

As a blog writer, I tend to think of the future in terms of posts. And this was supposed to be the one in which we celebrated Stuart becoming Canadian. He had new Hudson’s Bay mittens and everything, a citizenship gift from my mom. He passed his citizenship test a few weeks ago, and was called to take his oath this morning. He’d ironed his suit, located a tie (tricky business—most ties he ever had are now located in the children’s dress-up box and are used alternatively as head decorations and leashes for stuffed toys, irrevocably knotted) and we had a car booked to head out to Mississauga this morning for the eight o’clock appointment. We were so excited—I’ve been waiting years for this.

As a blog writer, I tend to think of the future in terms of posts. And this was supposed to be the one in which we celebrated Stuart becoming Canadian. He had new Hudson’s Bay mittens and everything, a citizenship gift from my mom. He passed his citizenship test a few weeks ago, and was called to take his oath this morning. He’d ironed his suit, located a tie (tricky business—most ties he ever had are now located in the children’s dress-up box and are used alternatively as head decorations and leashes for stuffed toys, irrevocably knotted) and we had a car booked to head out to Mississauga this morning for the eight o’clock appointment. We were so excited—I’ve been waiting years for this.

And then at two o’clock this morning, Iris woke up sick, and proceeded to be sick until she fell back asleep after five. It was not long before it was clear that us getting to Mississauga just wasn’t going to happen, and so we turned off the six o’clock alarm and I took Harriet to school this morning as usual (and she wasn’t so gutted about the whole thing—they’re celebrating their 100th day today and she was sorry to be missing that). Stuart has called immigration and has to write a letter requesting a rescheduling of his appointment, and so all should be well in time, but we’re disappointed. This was going to be a big deal. There should have been cake.

Alas. There will be cake—eventually. And in the meantime, Iris is sitting on the couch happily eating popsicles and watching Charlie and Lola, her stomach ailment causing her no trouble except, well, stomach related ones. We are consoling ourselves with the fact that we are leaving (without the children) for a trip to Barbados on Saturday.

February 19, 2016

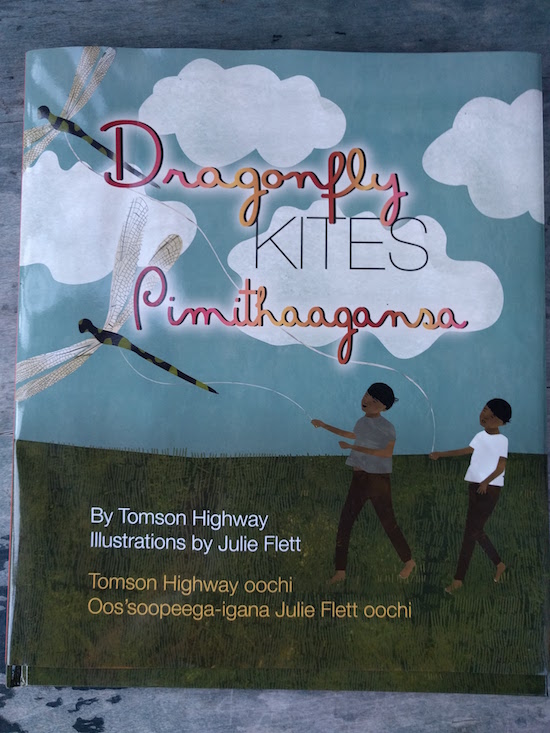

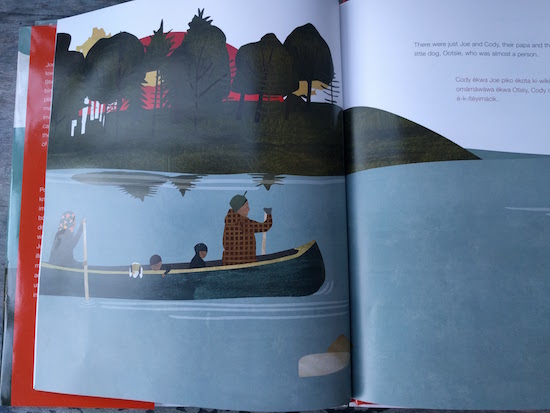

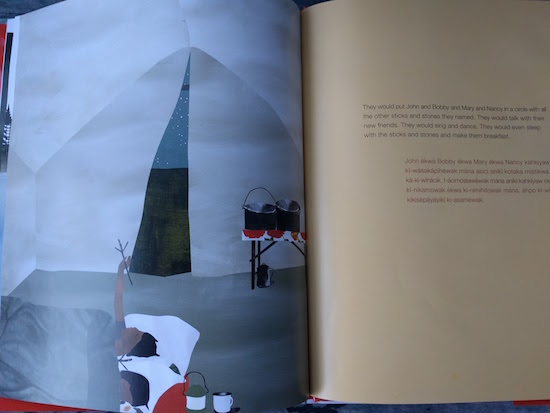

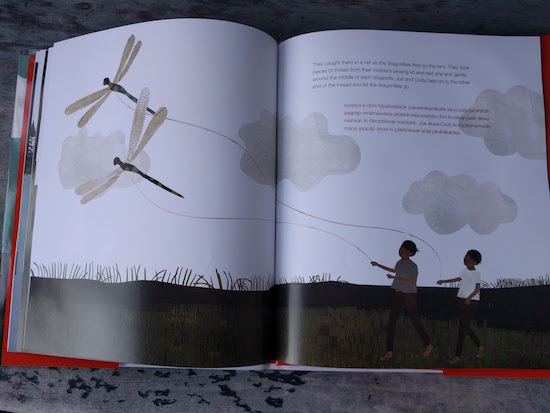

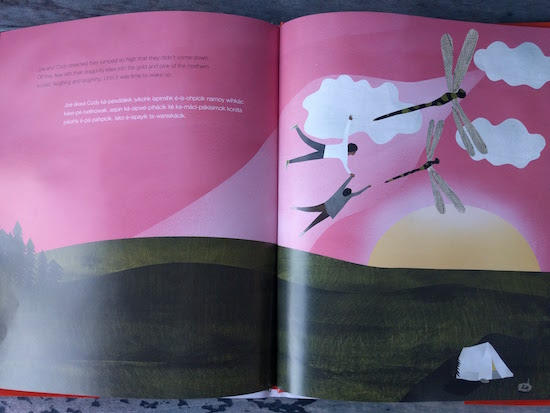

Dragonfly Kites, by Tomson Highway and Julie Flett

Just a week after bringing you a review of My Heart Fills With Happiness, by Monique Gray Smith and Julie Flett, I’m pleased to bring you another beautiful book illustrated by Flett. This one is Dragonfly Kites, written by Tomson Highway, who’s best known for his plays and works for adults (The Rez Sisters, Dry Lips Oughta Move to Kapuskasing, Kiss of the Fur Queen).

Like Flett’s illustrations, Highway’s story is gorgeous and simple. It features Cody and Joe, who appeared in his previous picture book, Caribou Song (and there is another in the works in this planned trilogy). The boys live with their parents in Northern Manitoba where there are so many lakes they’ve never stayed on the same one twice, and there are “islands and forests and beaches and clear water But no people.”

In this landscape, the boys make their own play, collecting sticks and giving them names, making up stories about the characters they become. (As we read this, I asked my city-dwelling children, “Do we know anybody who’d ever play a game like that?” and they both nodded, smiling at me.)

The story gives Flett the opportunity to do what she does best (and what she’s made a reputation for in books like Dolphin SOS, Wild Berries and Little You): beautiful scenes set in nature, highlighted with bright prints and patterns. Her talent shines in particular with her renderings of the dragon flies of the book’s title, with the gorgeous intricacies of their wings.

Joe and Cody name and play with many animals they encounter in the wild, but the dragonflies are their favourite. They catch the dragonflies in nets and tie threads around their middles, holding the strings with the dragonflies flying like kites. Which is the point at which the book really takes flight, and I’ll own up to googling “dragonfly kites” to find out if this is really something people do, and I don’t think it actually is, but that Highway made me wonder is a testament to this book’s magic. The dragonflies’ flight continuing long after the boys are tucked into bed at night, continuing on in their dreams, and now they’re soaring high with the insects, into the sunset, straight on until morning.

“That was a good one,” said Harriet when the story was over, the flight was done.

February 17, 2016

On Carol Shields, Rereading, and The Republic of Love

I’ve gone back off the grid in terms of reading, into backlists and rereads. The occasion of Valentines Day inspired me to pick up Shields’ The Republic of Love, which I read last in 2007, according to the note on the inside cover. (Apparently, I was much more organized in 2007.) I wrote a post about it too, and seemed to be as bowled over by the book’s goodness as I was this time (and also was struck between parallels between it and Lionel Shriver’s The Post-Birthday World, as I’d later see connections between Small Ceremonies and We Need to Talk About Kevin). I don’t remember how much I loved this book back in 2007, but what I do recall and experienced as a faint echo as I read The Republic of Love this time was how much it made me long to go out and write a book just like it. A sad kind of longing it was because my attempts to be Carol Shields at that point had come up very short and resulted in considerable rejections. (I once wrote a story that was a short story glosa with excerpts from a story in Shields’ Various Miracles, and one rejection I received explained that the inclusion of Carol Shields’ prose on the page with my own only made clear how much my prose was not by Carol Shields. Sigh.) This, this, this, I remember thinking, as I read The Republic of Love in 2007. This is what I want to do. And it was something to be recalling that now from the other side as I now read with a novel of my own.

I feel like I’ve grown up with Carol Shields. I received The Stone Diaries as a gift in high school from my mom, a lovely little compact hardcover, before all the awards, I think, because it has no stickers, and her biography was still celebrating The Republic of Love having been shortlisted for The Guardian Short Fiction Prize in 1992. And I loved it—it was easy to love. This was makes Shields work so easy to dismiss—as “light,” not serious. It was her world-building that did it for me, the inclusion of actual photos and a family tree, the poetry written by fictional characters. How the photos were (many of them) of Shields’ own family, and this amazing blurring between fact and fiction was fascinating to me. The novel would stand on its own without these additions, but they pushed its edges, its limits, in ways that were wonderful to somebody who is only just discovering what fiction can do.

I feel like I’ve grown up with Carol Shields. I received The Stone Diaries as a gift in high school from my mom, a lovely little compact hardcover, before all the awards, I think, because it has no stickers, and her biography was still celebrating The Republic of Love having been shortlisted for The Guardian Short Fiction Prize in 1992. And I loved it—it was easy to love. This was makes Shields work so easy to dismiss—as “light,” not serious. It was her world-building that did it for me, the inclusion of actual photos and a family tree, the poetry written by fictional characters. How the photos were (many of them) of Shields’ own family, and this amazing blurring between fact and fiction was fascinating to me. The novel would stand on its own without these additions, but they pushed its edges, its limits, in ways that were wonderful to somebody who is only just discovering what fiction can do.

Unless remains my favourite of all her books—I went into great detail to explain why in this post from 2011. It’s a book I’ve returned to again and again, and it’s been rich with surprises every time. Eventually, I’d read all her books, her short story collections. I bought Various Miracles in a used bookshop in Kobe in 2003, and remember reading with rapture. Larry’s Party, Happenstance. I reread Small Ceremonies a few years ago, and really loved it—even with her first novel, it was clear that this was a writer with tremendous vision. I loved her collection of letters with Blanche Howard—I’ve read that book twice and intend to return to it throughout my life. There’s so much wisdom from two remarkable women, about living and writing, marriage and motherhood, and it was they who inspired me to pick up Penelope Fitzgerald’s Home, and I’m so pleased that I did. I think that’s also the book in which Shields notes that she’s no longer jealous of others’ literary success (though perhaps that was in Carol Shields: The Arts of a Writing Life), which seemed like an impossible goal for me once upon a time, but I’ve found my way toward it. I was stirred too by the notes about her “talent for friendship”; Shields has been such an inspiration for me as a writer, a mother, a feminist, a friend.

Unless remains my favourite of all her books—I went into great detail to explain why in this post from 2011. It’s a book I’ve returned to again and again, and it’s been rich with surprises every time. Eventually, I’d read all her books, her short story collections. I bought Various Miracles in a used bookshop in Kobe in 2003, and remember reading with rapture. Larry’s Party, Happenstance. I reread Small Ceremonies a few years ago, and really loved it—even with her first novel, it was clear that this was a writer with tremendous vision. I loved her collection of letters with Blanche Howard—I’ve read that book twice and intend to return to it throughout my life. There’s so much wisdom from two remarkable women, about living and writing, marriage and motherhood, and it was they who inspired me to pick up Penelope Fitzgerald’s Home, and I’m so pleased that I did. I think that’s also the book in which Shields notes that she’s no longer jealous of others’ literary success (though perhaps that was in Carol Shields: The Arts of a Writing Life), which seemed like an impossible goal for me once upon a time, but I’ve found my way toward it. I was stirred too by the notes about her “talent for friendship”; Shields has been such an inspiration for me as a writer, a mother, a feminist, a friend.

I had no idea what to expect when I picked up The Republic of Love last weekend; I didn’t remember much about it. I wasn’t even sure I really wanted to read it because there are so many books waiting for me to read them for the first time, let alone reading this one for the third or fourth. But here were my impressions as I read it. First, I was hooked immediately. My husband was reading a book he was loving, and said to me a while into it, “I’m hooked now.” “I was hooked on this one in the first paragraph,” I replied. Or the first sentence? “As a baby, Tom Avery had twenty seven mothers.” I’d forgotten about that and though it was Larry from Larry’s Party with the 27 mothers, but but I remember now that he had just one mother and she went and committed botulism. Carol Shields is certainly one for memorable prologues. Also remarkable: Tom is the name of Reta’s husband in Unless. I guess Shields had run out of good men’s names, the stolid types, Toms, and Joes. I think a lot about authors who reuse names—Barbara Pym does this. And then I went and read somewhere that there was no meaning behind it: “With me it’s sometimes just laziness,” she wrote to Philip Larkin. “If I need a casual clergyman or anthropologist I just take one from an earlier book.”

I had no idea what to expect when I picked up The Republic of Love last weekend; I didn’t remember much about it. I wasn’t even sure I really wanted to read it because there are so many books waiting for me to read them for the first time, let alone reading this one for the third or fourth. But here were my impressions as I read it. First, I was hooked immediately. My husband was reading a book he was loving, and said to me a while into it, “I’m hooked now.” “I was hooked on this one in the first paragraph,” I replied. Or the first sentence? “As a baby, Tom Avery had twenty seven mothers.” I’d forgotten about that and though it was Larry from Larry’s Party with the 27 mothers, but but I remember now that he had just one mother and she went and committed botulism. Carol Shields is certainly one for memorable prologues. Also remarkable: Tom is the name of Reta’s husband in Unless. I guess Shields had run out of good men’s names, the stolid types, Toms, and Joes. I think a lot about authors who reuse names—Barbara Pym does this. And then I went and read somewhere that there was no meaning behind it: “With me it’s sometimes just laziness,” she wrote to Philip Larkin. “If I need a casual clergyman or anthropologist I just take one from an earlier book.”

Another thing that was important was that I’d visited Winnipeg since my last reread of The Republic of Love, which made the book’s sense of place all the more vivid to me. We’d even made a pilgrimage to the Project Bookmark marker on the corner of River Avenue and Osborne Street, speaking of blurring lines between truth and fiction. I’d essentially stood right there inside the passage of the book, and now there were the words on the page after I’d seen them right there in their world, and the effect was amazing.

Another thing that was important was that I’d visited Winnipeg since my last reread of The Republic of Love, which made the book’s sense of place all the more vivid to me. We’d even made a pilgrimage to the Project Bookmark marker on the corner of River Avenue and Osborne Street, speaking of blurring lines between truth and fiction. I’d essentially stood right there inside the passage of the book, and now there were the words on the page after I’d seen them right there in their world, and the effect was amazing.

Shields loved naming characters (gratuitous Toms notwithstanding), creating the webs, the family trees we see in The Stone Diaries. It seems unfathomable that the world of The Republic of Love is created, made-up, rich as it is with friendships and histories, and couples who knew each other since meeting at someone else’s wedding through somebody’s aunt a thousand years ago. We get entire paragraphs of people who turn up at a party whom we never see again in the book, but they add texture to the world of Shields’ love story here, that it’s never just about two people anyway. Because the lovers have parents, and ex-spouses, and ex-boyfriends who have moved back in with their ex-wife whose husband used to be married to the first wife of one’s fiance. A merry-go-round, Shields refers to it.

And oh yes, it’s about love: “It’s possible to speak ironically about romance, but no adult with any sense talks about love’s richness and transcendence, that it actually happens, that it’s happening right now, in the last years of our long, hard, lean, bitter and promiscuous century. Even here it’s happening, in this flat, midcontinental city with its half million people and its traffic and weather and asphalt parking lots and languishing flower borders and yellow-leafed trees—right here, the miracle of it.” (Which was precisely what I was getting at here.)

And oh yes, it’s about love: “It’s possible to speak ironically about romance, but no adult with any sense talks about love’s richness and transcendence, that it actually happens, that it’s happening right now, in the last years of our long, hard, lean, bitter and promiscuous century. Even here it’s happening, in this flat, midcontinental city with its half million people and its traffic and weather and asphalt parking lots and languishing flower borders and yellow-leafed trees—right here, the miracle of it.” (Which was precisely what I was getting at here.)

I am older than Fay McLeod, heroine of this story—this is weird to me. Though when you are 36 you start being unfathomably older than so many people and it’s totally bizarre. I have been married a decade and have two kids, but still think it’s strange that Fay McLeod is older than me, but that’s mostly because she’s never been older than me before in the entire time I’ve been reading her story, and it’s hard to get my head around that shift. Will I ever read this book and think that Fay McLeod seems young? When I am 53 and she is 35, I wonder? Though I still think that girls in the high school yearbook who were 18 when I was 14 seem more grown up than I’ll ever be, so maybe there is no cure for this affliction.

I am older than Fay McLeod, heroine of this story—this is weird to me. Though when you are 36 you start being unfathomably older than so many people and it’s totally bizarre. I have been married a decade and have two kids, but still think it’s strange that Fay McLeod is older than me, but that’s mostly because she’s never been older than me before in the entire time I’ve been reading her story, and it’s hard to get my head around that shift. Will I ever read this book and think that Fay McLeod seems young? When I am 53 and she is 35, I wonder? Though I still think that girls in the high school yearbook who were 18 when I was 14 seem more grown up than I’ll ever be, so maybe there is no cure for this affliction.

What else…. I love the late night radio in this story, perhaps (sadly) the one bit of the novel that is dated because all the local stations would syndicate something cheap for the hours between 12 and 4 am these days. I love those voices late in the night, the call-ins, and everybody with an opinion, something to say. I love the way that time sweeps here, through nearly a year, I think. How so much happens off-page, in the margins. The voices—how Shields lets them have their space without explaining that they’re there for. I love the way an aerogram letter is essential to the plot. The different points of view, misunderstandings, what is understood but doesn’t have to be said. How there is no plot, except that love is the plot. That one can make a plot with good, decent people who aren’t terrible to each other. This, this, this, was what I meant when I said that this was the kind of book I wanted to write.

What else…. I love the late night radio in this story, perhaps (sadly) the one bit of the novel that is dated because all the local stations would syndicate something cheap for the hours between 12 and 4 am these days. I love those voices late in the night, the call-ins, and everybody with an opinion, something to say. I love the way that time sweeps here, through nearly a year, I think. How so much happens off-page, in the margins. The voices—how Shields lets them have their space without explaining that they’re there for. I love the way an aerogram letter is essential to the plot. The different points of view, misunderstandings, what is understood but doesn’t have to be said. How there is no plot, except that love is the plot. That one can make a plot with good, decent people who aren’t terrible to each other. This, this, this, was what I meant when I said that this was the kind of book I wanted to write.

There is a lovely line by Elizabeth Hay in her essay from the PEN anthology, The Writing Life, that I underlined when I read it first in 2006: “What I’m doing is catching a ride on the coattails on literature.” YES. It occurred to me too how foundational all of Shields’ work has been for me, finding its way into my literary DNA and while I’m still no Carol Shields, her stories and ideas and preoccupations are echoing away in every paragraph I write. If not for her and all her work, I might be whiling away my time in a literary no-womansland.

PS I am excited about Startle and Illuminate, a new book of Shields’ advice on writing, which is forthcoming this April.