May 9, 2016

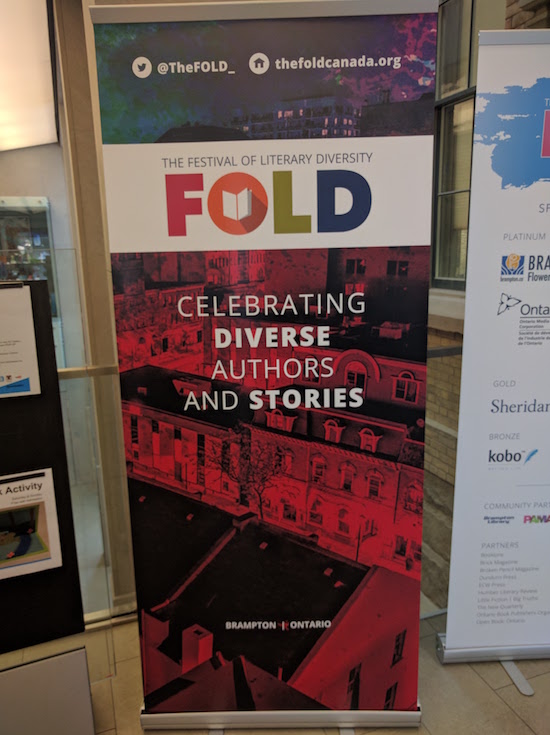

The Festival of Literary Diversity

Warning: There’s gonna be typos, as I translate my pages and pages of handwritten notes into a blog post. Forgive me, please?

From the start, The Festival of Literary Diversity (FOLD) seemed to me like a most inspired idea, one whose time was exactly right, although my enthusiasm was mostly theoretical. Because, and here’s my confession, for all my lit championship, there are few events I’d choose to attend over, say, staying home and reading. I don’t need to discover new books and authors, I feel connected enough to the literary scene, and I’d rather read an author’s work than hear her answers at a Q&A.

But then the FOLD rolled out their schedule, and I was as excited as I was impressed. Not only did it seem like something I should go to, but now I actually wanted to. I’ve been going to literary festivals for years, but these were panels apart from anything I’ve ever attended before. These sessions were asking questions whose answers I had no idea about—what an incredible opportunity for learning. There were also writers whose work I was familiar with, but others I hadn’t encountered before. I knew that I absolutely had to be a part of it, and it was pretty easy to find three writer friends who wanted to come along.

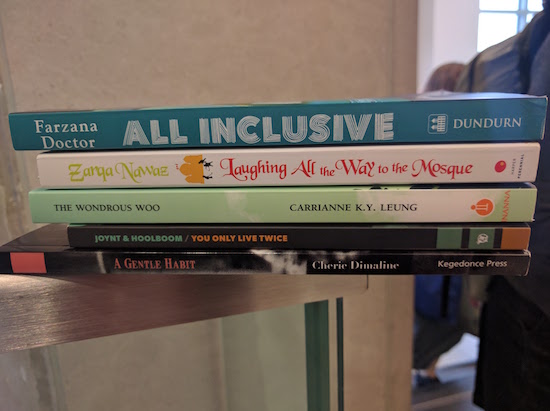

Although we took a wrong turn off the 410, so were late for the Faith and Fiction panel. As we walked in, Zarqa Nawaz (author of the memoir Laughing All the Way to the Mosque and an actor from the TV series Little Mosque on the Prairie) was discussing the universal struggle for social justice, how it was not just particular to faith communities. She gave the example of women who are restricted from attending school in France because of wearing religious dress—secular and fundamentalists both, she explained, are capable of denying a woman eduction due to dogmatic beliefs.

Although we took a wrong turn off the 410, so were late for the Faith and Fiction panel. As we walked in, Zarqa Nawaz (author of the memoir Laughing All the Way to the Mosque and an actor from the TV series Little Mosque on the Prairie) was discussing the universal struggle for social justice, how it was not just particular to faith communities. She gave the example of women who are restricted from attending school in France because of wearing religious dress—secular and fundamentalists both, she explained, are capable of denying a woman eduction due to dogmatic beliefs.

Cherie Dimaline (an award-winning Métis writer whose most recent book is the short story collection A Gentle Habit) told us that for her, stories themselves were a faith, and that repetition was used in storytelling as a way to keep the stories, “to develop the brain like a beehive,” she said. She’d been selected in her family when she was young as a story-keeper and her responsibility in this respect is to the seven generations before and after her, to reach back and also reach forward.

Ayelet Tsabari (author of The Best Place on Earth) continued this connecting of faith and story. In order to write, she explained, you need a tremendous amount of faith—in one’s self, in the reader and also in the possibility of fiction changing the world even in the smallest ways. “You can write fiction without faith,” she said, “but it’s much harder.” And then she noted how for her, writing was very much a spiritual practice, with ritual, an insistence on objects, and a whole lot of praying. “Aside from parenthood,” she explained, “[writing] is the one thing I take seriously, where I find meaning.”

Nawaz talked about Muslim women and victim literature. “A boring suburban life was really radical for a Muslim woman,” she noted. In publicity for her work, she finds herself being defined as someone belonging to a violent faith that doesn’t believe in comedy. She tries to find a way to talk about her community in ways that are fair and also challenge stereotypes. An interviewer in the US mentioned responses to Little Mosque on the Prairie, and Nawaz countered that with Christian responses to the film The Last Temptation of Christ, or the furor when Sinead O’Connor ripped up a photo of the Pope on TV. “There’s cultural amnesia,” she said. “The examples are everywhere.” The stereotypes are so entrenched, but it ultimately it all comes down to the fact that people everywhere are all the same.

Dimaline continued the thread about stereotypes and their entrenchment. People, she said, can be upset when their expectations are disrupted. Her novel, The Girl Who Built a Galaxy, begins with a girl and her grandfather, familiar territory for a Indigenous story. But then it takes a twist and the girl ends up in New Orleans, which threw a few readers. “‘Where’s her canoe?'” Dimaline has her hypothetical reader asking, answering that reader’s question with, “You know, we also exist outside your imaginations.”

“Writing,” says Dimaline, “is the last true magic. Imagine being able to create something out of nothing,” and that something is what literature is. It takes faith to create it, and also to receive it.

Moderator Eufemia Fantetti asked about criticism of writers’ portrayal of faith. “I try to listen to feedback,” answered Vivek Shraya, the multidisciplinary artist whose latest book is the poetry collection even this page is white. The feedback is not always useful, but can be, says Shraya, as she embarks in work like her recent work, She of the Mountains, which reimagines Hindu mythology through a feminist lens. She went on to talk about the importance of not underestimating one’s audience. It’s been tricky having a book about queerness with “God” in the title, but sometimes, she said, you have to trust your muse. And people have connected with these stories in all kinds of surprising ways. Diverse books are important because people get to see their own experiences reflected, but these books are also good for readers who can connect with different perspectives.

Tsabari said that the story she was most afraid to publish for fear of controversy (the story of an Israeli woman who comes to Canada to meet her new grandchild, and discovers the boy will not be circumcised) was the one which has received the most overwhelming emotional response. That often a writer has to write about what scares her. And the stakes seem even higher now as her book is about to published in Canada. “It’s all scary,” she said. “That’s why we need faith.”

Both Nawaz and Dimaline talked about how the threat of right-wing tyranny has galvanized their respective communities, Nawaz in response to 9/11 and Dimaline with Idle No More, and has had Muslim and First Nation communities come out of isolation and begin to engage, to shape their own narrative after years of invisibility.

Next up was the Powerful Protagonists Panel with Brian Francis (Fruit, Natural Order), Sabrina Ramnanan (Nothing Like Love), Waubgeshig Rice (Legacy), and Heather O’Neill (The Girl Who Was Saturday Night, The Daydreams of Angels). Each author read from their recent works, and then a discussion began, moderated by Aga Maksimovska.

Next up was the Powerful Protagonists Panel with Brian Francis (Fruit, Natural Order), Sabrina Ramnanan (Nothing Like Love), Waubgeshig Rice (Legacy), and Heather O’Neill (The Girl Who Was Saturday Night, The Daydreams of Angels). Each author read from their recent works, and then a discussion began, moderated by Aga Maksimovska.

His own powerful protagonist, said Francis, was born of his interest in older generations and the way they kept private and personal stories close, linked to pain and shame. What if, he wondered, he wrote a character who tried to escape from that?

Ramnanan’s protagonist was one who, after a sudden fall from grace, was surprised to discover she was vulnerable, that as a woman she was forced to adhere to different standards than the boys were. She is disgraced and then furthermore when she learns that the man she loves is going to marry somebody else. And she achieves her power when she makes the decision to go and confront that woman her love is due to marry, and in doing so changes the course of her life and also that of the people in her village

Rice’s character in Legacy is one who is powerful because she doesn’t believe what the world tells her about herself and her people, and because she carves out a path for herself, coming to the city to pursue an education at a time when this wasn’t common for First Nations women, thereby laying a path for future generations.

O’Neill said that her fascination is with protagonists who have to learn how to be themselves in surprising contexts, in the midst of narratives where they mightn’t feel that they belong. “We are not our contexts,” she said. “We strive against our contexts.”

The writers talked about when their protagonists are a little them, and also about the opportunity to live vicariously through their characters. In response to the question of character likability, Francis commented that it’s so much more important that characters be interesting. Ramnanan would prefer her characters be memorable. Even if a reader doesn’t like a character, said Rice, at least the character is invoking a reaction. And O’Neill said that for her as a novelist, creating likeable characters is a driving force. She sets challenges for herself of making the most unappealing characters loveable—and through that, the reader can have a growth experience.

They talked about characters as witnesses, and whether or not it’s easier or harder to write a character who is more or less like you, and whether plot comes first or character (and the answers were varied). They were asked about building a character’s strength, and O’Neill said that she likes to start her characters so far down that there’s nowhere for them to go but up. Francis considered the question of whether a character must necessarily triumph. And what kind of characters do they struggle with? O’Neill has never been able to write a mother; Rice was nervous about writing in the perspective of a woman, but drew from the women around him to get it right; Ramnanan has more trouble writing about experiences closer to her own than writing wholly imagined ones; and Francis said that he’s conscious of writing about family—that everyone imagines himself the hero of his own story, and it disturbs everything when a writer goes and upsets that narrative.

And then we broke for lunch! There were several options right there in the venue (which was fantastic, by the way, as was the organization of the event and how completely wonderful it was to be there) and we ended up having wraps and salads. After that was a browse in the pop-up bookstore, which was being put on by Orangeville’s Booklore. And then we needed tea, of course, so we went exploring historic downtown Brampton (including a band playing in the town square, the audience in comfy Muskoka chairs) to find T by Daniel, where we all partook in a cuppa and took a selfie of our crew.

And then we broke for lunch! There were several options right there in the venue (which was fantastic, by the way, as was the organization of the event and how completely wonderful it was to be there) and we ended up having wraps and salads. After that was a browse in the pop-up bookstore, which was being put on by Orangeville’s Booklore. And then we needed tea, of course, so we went exploring historic downtown Brampton (including a band playing in the town square, the audience in comfy Muskoka chairs) to find T by Daniel, where we all partook in a cuppa and took a selfie of our crew.

Which meant that we were late again for the next panel, Defying Boundaries, with Vivek Shraya, Chase Joynt, and Zoe Whittall. When we finally sauntered in, Shraya was discussing faith and queerness. Joynt began explaining that transness was not just about gender, but about the experience of finding kinship with wider communities. Both writers were asked about defying boundaries as mutual-media artists, and Shraya answers that while her foundation in music sometimes makes her feel like a fraud as a writer, that each form informs the others. Every form is limited, said Joynt, and it’s useful to be able to go beyond those limits.

Which meant that we were late again for the next panel, Defying Boundaries, with Vivek Shraya, Chase Joynt, and Zoe Whittall. When we finally sauntered in, Shraya was discussing faith and queerness. Joynt began explaining that transness was not just about gender, but about the experience of finding kinship with wider communities. Both writers were asked about defying boundaries as mutual-media artists, and Shraya answers that while her foundation in music sometimes makes her feel like a fraud as a writer, that each form informs the others. Every form is limited, said Joynt, and it’s useful to be able to go beyond those limits.

Both artists are also prolific collaborators. “Stories are more powerful with more voices involved,” explained Joynt, and Shraya noted the benefits of getting different perspectives on a project and learning to work with others. They’d been talking about this in regards to different approaches to social media. And Shraya remarked that for her, coming from a self-published, indie background, social media and self-promotion had never been a choice, which made it frustrating to have to listen to older authors complaining about this part of the job. She talked about the selfie as a political strategy for queer people of colour—what a radical act it was to take up space like that. She talked about moving from self-publishing to traditional publishing, and how while there are benefits (getting your books into bookstores being one), there’s still a lot of work required on the part of the artist. Joynt spoke about moving away from academic writing, and the freedom in that, and also about how he’s inspired by artists like Claudia Rankine and Maggie Nelson and their experimental citation strategies.

Joynt talked about his intent upon destabilization of trans narrative, and Shraya concurred: “If I’m going to transmit a narrative of femininity, it’s going to have hair.” When asked about her new book about racism, Shraya noted she was conscious of the privilege inherent in her experience in terms of anti-Black racism and First Nations racism, and she had to think about how to articulate her own complicity.

An audience member asked a question about trans narratives, and the prevalence of depressing themes, and Joynt expressed interest in the question of who gets to be fun. How do we account for the devastating impact of transphobia and give people room to be fun?

Joynt talked about memoir and the construction of story, and how his mom factored into it differently than other characters because she was the one stable force—his mom was always going to be his mom—and so he needed her permission to share her experience. Although Shraya’s take on this idea was very different—she hadn’t asked her mother about including her in the recent project, Trisha because she was going to do it anyway, so this way she didn’t have to go to the trouble of having her mother refuse her. And this all made me think about whether that kind of freedom goes both ways, and what kind of obligation a mother has to her child in regards to making art and telling stories. And was just one of the many additional questions that this fascinating panel led to.

And then finally it was time for Publishing (More) Diverse Stories, with Anita Chong from Penguin Random House, Barbara Howson from House of Anansi, Bianca Spence from the Ontario Media Development Corporation, Rachel Thompson from ROOM Magazine, and Susan Travis from Scholastic Canada, moderated by the amazing Léonicka Valcius who’s even more fantastic in person than you’d expect (which is saying something). Truly a knockout panel, all of them, and I’d really been looking forward to this.

And then finally it was time for Publishing (More) Diverse Stories, with Anita Chong from Penguin Random House, Barbara Howson from House of Anansi, Bianca Spence from the Ontario Media Development Corporation, Rachel Thompson from ROOM Magazine, and Susan Travis from Scholastic Canada, moderated by the amazing Léonicka Valcius who’s even more fantastic in person than you’d expect (which is saying something). Truly a knockout panel, all of them, and I’d really been looking forward to this.

Chong responded to the first question, about her ideal diverse book publishing ecosystem, by explaining that we need a wider pool of readers. There is the typical reader (40-60, white, woman) but she’s not everyone. Those in publishing need a greater understanding of who readers are, and to that end, there needs to be a wider talent pool throughout the entire industry—not just writers or at the publisher level either.

Howson took on the question then of how to widen that readership, and the answer is to publish different voices to include new perspectives, younger people. She noted how difficult it is for people outside of a select socio-economic level to enter the industry, and would like to make it easier for them to do so.

Travis, who works in sales, spoke about broadening the variety of what she has to offer buyers (who are booksellers). Diverse has to mean substance—it’s not just about giving a kid in a picture book brown skin. She explained that buyers are cautious, that they tend to be old-guard, and that perhaps their caution is understandable given the realities of their industry. The people they’ve got working on the floor though, actually hand-selling the books, are more open-minded, and they’re the people that Travis approaches.

How to widen the pool then? Thompson spoke about her experiences at ROOM magazine, and efforts to transform their volunteer editorial board to reflect a more diverse make-up. She noted that an ideal landscape in terms of diversity would mean a magazine like ROOM (with a feminist mandate, publishing women) would not need to exist.

Spence reflected on the nature of arts funding, as well as the costs of getting into publishing via college or university publishing programs and/or internships, and wondered what would happen to the landscape and what kind of new perspectives might be discovered if these elite, expensive experiences were no longer regarded as pre-requisites for publishing careers.

Chong said that she’s so tired of being the only non-white person in the room, and that she continues to insist that inclusiveness doesn’t mean a lowering of standards. Widening the pool only means that you’re going to get something new. She spoke of her experience with the Journey Prize, and how she continually asks herself how she can run this program better. It’s about challenging your own expectations. For her, a solution was ensuring a diverse jury for the prize, and the results have only made the program stronger.

Howson talked about Groundwood Books, which has always had a diverse mandate, perhaps because its founder came from Guatemala and so brought with her another language and a different kind of point of view. And Groundwood has been publishing Spanish books and books from other cultures for years, which made the recent #WeNeedDiverseBooks movement a bit annoying from their perspectives in that they were being overlooked. And so to find a way to say, “Hey! We’re here!” they created a catalogue highlighting those diverse titles. Similarly, House of Anansi created Anansi International, looking for voices from around the world, and has a list of French Canadian titles.

It’s a question of finding and highlighting diverse voices, and working with marketers and the gatekeepers in stores to make it all happen.

Travis sees this as her job, keeping the conversations going, not just having diverse titles ghettoized, but having them integrated into stock. And making sure that conversation gets to the people who are actually selling the books, who are not necessarily store owners.

Spence says that as she is often the only person of colour in the room, she sees it as her job to ask tough questions to make people think about who gets included and why. She also likes to make connections with people just coming up in the industry and serving as an example, make connections and taking on mentorship roles. She encourages others in publishing to make their own connections with people of colour, to diversify networks and communities that way.

Thompson talked about the politics and diplomacy required in transforming communities. At ROOM, their focus was bringing in new people, a new diverse team. An example since then has been their Women of Colour issue, which was hugely successful—their call for submission went viral, and the issue entirely sold out. She’s hoping that their peers in the industry will undertake similar initiatives—they have had such success, but is left wondering why everybody else is so far behind.

Chong said that it all comes down to economics, and who can afford to be in the industry. There is one thing that we can all do though, which is to BUY THE BOOKS. Going to the library is not good enough. There is data about what sells, and if it sells, that data is irrefutable.

Spence said too that we have to make room for more diverse books. How come there can be twelve books about young white women working in the city, but only one Guatemalan book? To which Chong chimed in with annoyance at the way that diverse books are only read at certain times of year, like Black History Month, or Chinese New Year.

Howson noted though that even those who can’t afford to buy books can make a difference by using the library—ordering the books, putting on holds. The library is another place where the reader can demand diverse books.

Valcius added that it’s not all about data and economics though, and she is wary of the idea that it all comes down to the buyers and their agency. Because there are some books that don’t sell, but they still need to be published. Buying books is important, but it’s not all a numbers game.

“We publish poetry,” said Howson. “It’s not a numbers game.” But it’s still important to get a wide audience, to get the numbers up. And also to get books into schools. (Travis gave the example of BC schools’ changing curriculum and new demand for First Nations stories.)

Spence pointed out that writers need to be able to make money. That media outlets need to cover more books, and that shrinking coverage just means that everyone is reading the same 12 books. We need more diverse coverage of books. And that publishing salaries are pitifully low.

Writers these days need full-time jobs, says Chong, fearing for a point at which the only people who can afford to be writers are middle-class.

Thompson explains that ROOM has strategy for diversity now, and that everything they do is measured by it now. And funders are now asking for this to be part of programs, so it’s working for them, and enabling them to pay more people to work for the magazine, which widens their talent pool. They also have found themselves with increasing numbers of subscribers.

The panel took questions from the audience, many of whom were writers who felt the doors were closed to them. This idea was refuted by Chong, who noted how important it is for her to see diverse stories embraced for their universality, to see marginal stories brought into the centre. “There is a hunger for new voices,” she said. What these writers may be perceiving as a weakness isn’t necessarily so.

Spence brought up Shakespeare, and how readers are taught to push through the difficulty in accessing his work. Those picking up books by diverse writers need to be similarly encouraged to get past perceived difficulties such as dialect and find the universal.

“And talk about the universal,” said Howson. “That’s how you sell it.”

Valcius finished things up by suggesting it might help too to keep a sign hanging on the gate, one that says, “Hey, we’re open!”

AND SO. It was everything I hoped for and more. Panelists Nawaz, Dimaline and Joynt sold their books to me by virtue of their stellar presentations. I bought others I’ve been looking forward to reading. I came away inspired and full of questions and ideas, and I’m not the only one. Kudos for Jael Richardson and Léonicka Valcius, two incredible women, for making it all happen, with the help of their fantastic team and their great volunteers. And what I’ve written here only represents one day of three days of programming, not to mention the other panels, workshops and events that were taking place on Saturday while we were there.

So yes, this was a big deal. Hopefully the start of something bigger.

“So often on a panel I am the token. It’s exciting how much more nuanced the conversation is when there are many diverse voices,” tweeted Vivek Shraya after the fact, and it’s so entirely true. The difference for those of us who were there was entirely palpable.

May 9, 2016

Books are not going away

“Books are not going away any more than family is going away, any more than community is going away, anymore than love and intellectual inquiry are ever going away. Poetry is never going away—and yes, it’s important to keep these two ideas in your head at the same time: 1) hardly anyone reads poetry and 2) poetry has always existed.”

“Books are not going away any more than family is going away, any more than community is going away, anymore than love and intellectual inquiry are ever going away. Poetry is never going away—and yes, it’s important to keep these two ideas in your head at the same time: 1) hardly anyone reads poetry and 2) poetry has always existed.”

—Lynn Coady, Who Needs Books?

May 8, 2016

On Mother’s Day

Sunday morning, and I am reclining on the spine of a very, very good weekend, late Friday night aside. I can’t tell you about Friday night because I am a mother who makes a point of keeping my children’s dignity intact, but my goodness, what a story I could tell you over a nice cup of tea. Motherhood is lousy with unsavoury, monstrous things, when it’s not blinding with moments of pure, shining light. But we’re thirty six hours after that now. I spent yesterday in Brampton at The Fold Festival, with three wonderful friends keeping me company on the road and throughout. The day was inspiring and terrific, and I can’t wait to tell you all about it. I arrived home last night to dinner on the table, and a happy rest-of family who’d spent their own very good day together.

And now today is Mother’s Day, and I find myself appreciating my own mother even more than usual for how she saved our family when I was ill last December and cared for my children for a week this winter so my husband and I could celebrate our tenth anniversary in tropical climes. Where would any of us be without her? Certainly never, ever in Barbados. But as my mother is across the country today with her other favourite daughter and other favourite grandchildren, I get to be the star of my own show. Which means breakfast in bed and reading so many papers that my thumbs turned black. Iris gave me a flower she’d planted at playschool, and Harriet gave me a painting she’d made of irises, so floral is the theme. And Stuart gave me a book and a teacup, so he knows me well too. And what I want for the rest of the day is to make soup for lunch (I have become addicted to my immersion blender), to spend some time cleaning up the leaves and seasonal detritus from our backyard, and a little bit of hammock time. Followed by dinner at my favourite restaurant.

This morning I was brushing my teeth and perusing the row of books lined up beside my bathroom sink, and figured it was a good day for a flip through White Ink: Poems on Mothers and Motherhood, edited by Rishma Dunlop, who died a few weeks ago—Priscila Uppal’s eulogy for her friend is extraordinarily good. And I came to the poem “On Mother’s Day,” by Grace Paley, which is tangled, beautiful, sad and very funny, just like motherhood, just like life is. And I am so glad I did…

Suddenly before my eyes twenty-two transvestitesin joyous parade stuffed pillows undertheir lovely gownsand entered a restaurantunder a sign which said All Pregnant Mothers FreeI watched them place napkins over their belliesand accept coffee and zabaglioneI am especially open to sadness and hilaritysince my father died as a childone week ago in this his ninetieth year

May 6, 2016

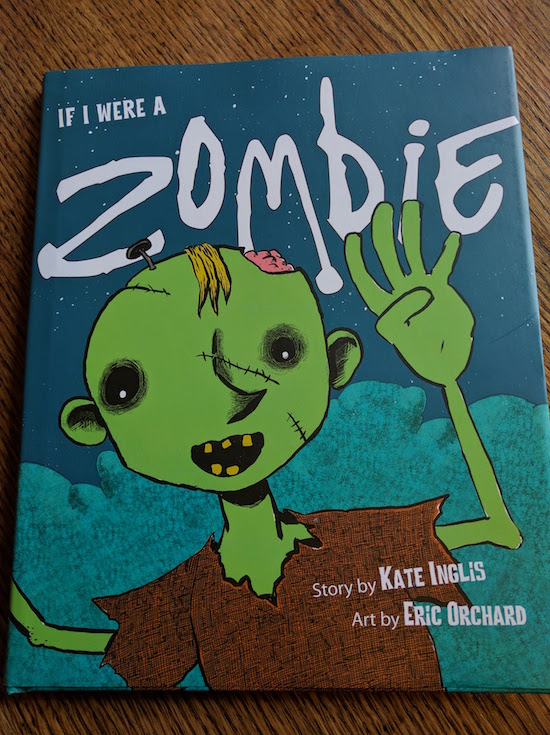

If I Were a Zombie, by Kate Inglis and Eric Orchard

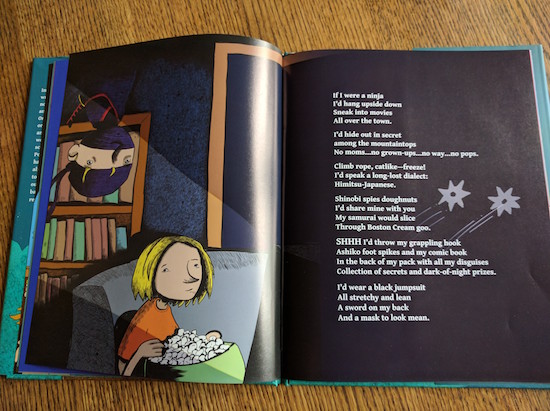

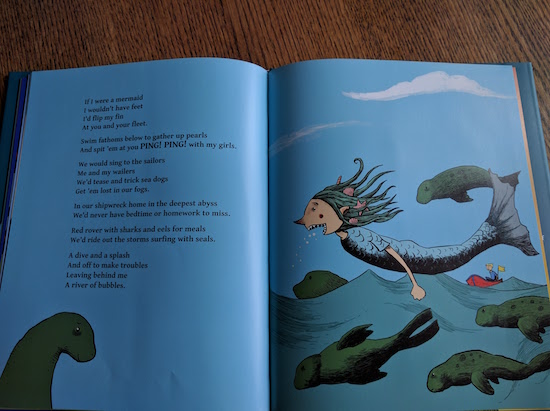

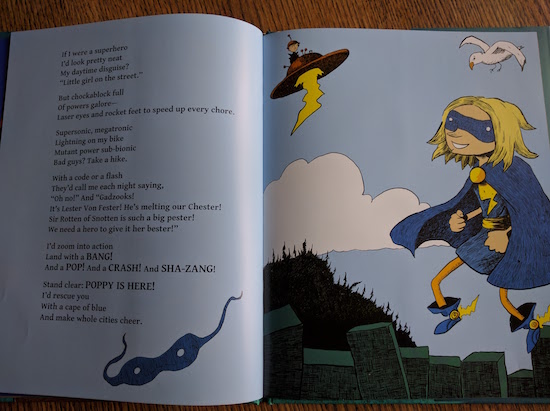

True confession: I don’t really get zombies. Along with “Talk Like a Pirate Day” and Nutella, zombies are a wildly popular phenomena whose appeal I just don’t understand. (I also have no strong feelings about Prince or Shakespeare, which made last week kind of strange.) What I do like is a beautiful picture book though, a kid-friendly one that my children delight in as much as I do, and so to that end, the undead notwithstanding, Kate Inglis’ latest book, If I Were A Zombie, illustrated by Eric Orchard, totally delivers.

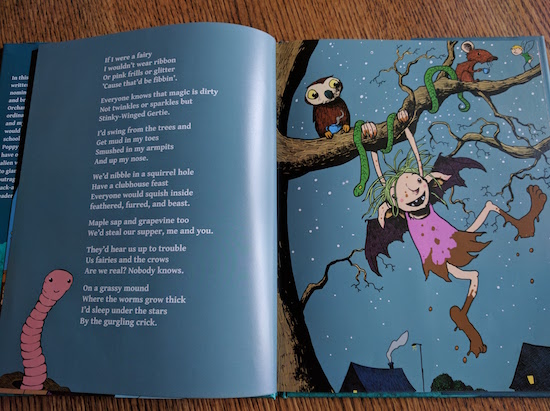

The premise is this: the narrator explores the various possibilities for selfhood amidst the kinds of creatures with children tend to be most fascinated: fairies, giants, witches, pirates and vampires. And even actual ninjas! Plus the zombies, of course.

The text is poetry, whose structure reminds me of Sleeping Dragons All Around, by Sheree Fitch (which is by the same publisher). Admittedly, rhyming couplets would have made for an easier read—sometimes the prose is tricky to say, and it’s hard to keep a rhythm—but I am not sure that such bounciness was ever Inglis’s intention. This is also a book that older children will read on their own which makes matters of rhythm irrelevant. And read it, they will. This is a book with zombies and ninjas after all. But there is more to it than that—this is a book about exploring all kinds of being, about possibilities, and adventure, and dreaming up stories for our lives. Teachers and other grown-ups will easily be able to encourage young readers to explore all kinds of “If I were….”s of their own, after trying out the various roles suggested in the book.

My very favourite thing about If I Were a Zombie though is its treatment of gender, assuming boys and girls alike as its readership—and also that all possibilities in the story are open to both of them as well. For a boy to have fairies and mermaids in his story—and I love Orchard’s non-cutesy takes on these. For children to read a book in which the superhero is a girl, which is particularly appealing to my superhero-loving daughter too. I love how gender becomes completely irrelevant, and all possibilities are open to either.

PS: If I Were a Zombie makes a very cool companion to Vikki VanSickle’s If I Had a Gryphon, but concerned with monsters and imagined creatures, as well as the conditional tense.

May 5, 2016

The M Word: Ariel Gordon’s Additional Dependent

This is the sixth in a series of posts catching up writers from The M Word, and finding out what they’re up to now. (Find out more about The M Word and read its rave reviews right here.) From previous weeks: “Kerry Ryan on Wishing and Washing“; “Heather Birrell on Talking to her (M)Other Self”; “Dear Me, by Nicole Dixon“; “Kerry Clare on Motherhood and Abortion” ; and “Christa Couture: Ever Since the End.”

“Primipara,” Ariel Gordon’s essay from The M Word about her choice to have one child, was one of the most widely remarked upon in the book’s critical responses—not least for its inclusion of her poem of the same name which began, “If I had had twins, I would have eaten one.” It was Gordon’s essay that earned The M Word its unlikely place on Brain Child Magazine’s Humour Book List last year. And now she catches us up to the very surprising news that her family has since acquired a new addition.

*****

My partner and I were together for seven years before we got knocked up.

It took us another decade to acquire an additional dependent.

In those ten years—the age of many of my friend’s marriages before they busted up—we had a tank full of fish which included Downie, a black Asian Upside-down Catfish.

We hand-fed Downie shrimp pellets, until those weren’t enough and s/he started eating everyone else. (One fish leapt to his/her death to avoid Downie’s jaws-of-death. S/he became fish-jerky between the dresser where the tank sat and the wall: “It smells in my room,” my daughter noted.)

We surrendered Downie to the pet store. We didn’t mention s/he was a cannibal.

Next we got black-and-white Mollies, which are starter fishes like Tetras, the difference being that they are prolific breeders. One female came pre-loaded with enough sperm that she gave birth every month for six months. She was the alpha: she got huge and monstrous and wouldn’t let any of the other Mollies eat, nipping their fins and head-butting them. And then she’d release a brood of baby Mollies, which looked like flecks of ash. They’d hide in the aquatic plants we grew in the tank, which came from the store infested with snails.

We surrendered entire litters of small black Mollies to the pet store.

After we drained the fish tank, my daughter pined, though she’d shown very little interest in the fish.

“I want a real pet,” she said. “Can we get a real pet?”

The summer after we drained the tank, we found a greeny-yellowy wild salamander swimming in the pool with us at the water park in Portage La Prairie. That fall, someone brought a carsick hedgehog to daycare. (“It pooped on two of my friends,” my daughter reported, excited.)

So we had serious conversations about salamanders, lizards, and geckos and then hedgehogs, guinea pigs, and rats. Anna pushed for a cat or a dog, though what she really wanted was a perpetual kitten or puppy. I resisted, citing my furry-animal allergies, but was glad that the conversation was about having-a-pet and not about having-a-sister/brother.

Now, I don’t watch kitten videos or hunt baby animals on the Internet. But when summer rolled around again and a friend posted pictures of a small white kitten stretched out, yawning, I felt a pang.

A friend of hers was trying to find homes for three kittens, including the white one. It turned out that I knew the friend-of-a-friend, so one Sunday, we went to go see them. The girl could barely contain herself on the way there, but neither of us connected with the kitten, so next we visited a no-kill shelter. I sneezed, my nose dripped, but we were both suddenly determined.

A week or so later, we brought home a half-grown black-and-white cat.

We only wanted one child and we similarly only wanted one cat. Not two or three, or a cat and a dog. One cat. But, unlike my daughter, we’ve so far managed to keep the cat out of our bed.

My boss and I commute to work together. When I told him we’d gotten a cat, he had one question.

“Who’s home the most?”

“I am,” I answered.

“She’ll love you best, then,” he said. He said with pets it’s a combination of who spends the most time with them and who feeds them.

This logic could equally be applied to children, of course. Mothers are still most often the ones home with their children when they are babies, primarily because they gave birth to them and have the boobs with which to feed them with. But I’m sure half the reason that mothers often have such strong bonds with their children is because they spend all those endless early days and weeks and months with them, skin on skin.

My boss was right. Given a choice, Kitty prefers to sit on my boobs, wedge her knobby spine under my chin, and listen to my heartbeat. She bunts my glasses aside, spreading contentment pheromone all over the bones of my face. If she’s feeling particularly tender, she licks my eyelids.

According to the Internet, this is submissive behaviour. She’d do the same to the alpha if she lived in a community of cats. She also rolls on the ground the moment the front door opens, showing her belly, as if to say “Hello, big hairless cats! Please love/feed me…”

Nowadays, people refer to their pets as furbabies and to themselves as their pets’ parents. But I prefer to think of myself as a cat that is slightly higher than Kitty in the social hierarchy. I have certain responsibilities to her—and affection for her— but I am not her parent.

Last night, after the girl had gone to bed, I was sitting on the couch and Kitty assumed her usual position. Except this time, she reached out and softly put her black-and-white paw on my eyelid. After a few moments, she tucked both paws under her body and promptly fell asleep.

When I was breastfeeding my daughter, I was often aware that I was putting my nipple into a mouth full of irrational teeth, that I was trusting her not to bite me.

Kitty’s paw is full of sickle-shaped claws. Her mouth is full of needles. But I am still willing to offer her my softest bits.

I’m good with animals, even if I don’t need them, if that makes any sense. When I was a kid, delivering newspapers in my neighbourhood, I came to an understanding with each of the neighbourhood dogs. They stopped barking at me when I entered their territory; some of them even offered me their bellies to rub.

Once, I was walking down my street at night and saw a dog-shaped animal twenty feet away. When I got a bit closer, I saw that it was a red fox. But I still bent down and offered my hand and said soft things, trying to tempt it to closer. We looked at each other for long moments, but it was wild and eventually loped away. I hold that memory close, the same way I hold the memory of watching my late uncle dandle my youngest cousin when she was two weeks old, the way I hold the memory of that hot summer when my daughter was born, how naked we both were.

My daughter had hoped that the cat would be hers, that it would love her best, but I tell her that Kitty loves all of us differently. I tell her she has to be more patient with the cat, let it come to her, but she’s almost ten now and isn’t very patient.

What’s more, she’s starting to push me, alternating pouting with correcting every single thing I say. I am embarrassing, she says.

I tell her I could be much more embarrassing, given half a chance. She squints at me.

Today, between karate and groceries, the girl was hungry, so we stopped at Tim Horton’s for a bagel and cream cheese. And she pouted because I wouldn’t get her a Frozen Lemonade or a Maple Cinnamon French Toast bagel, restricting her to the tap water I’d brought from home and a Twelve Grain bagel.

We’d made it through the drive-through and were sitting at the light and she was lifting my water bottle to her mouth when the light changed. I moved smoothly into the intersection and had just completed my left turn when she yelped.

“What?” I said.

“Waaaaaah,” she replied.

“Anna, what?”

“You—jerked—the car…”

“Anna, I was driving. I didn’t jerk the car.”

“You made me spill the water all over myself…”

A sniffly moment of silence.

“Here, blot yourself.” I passed her the box of tissues I keep in the front seat.

“I don’t even know what that means.”

“It means pat yourself with the tissues.”

“Like that’ll make a difference…”

“Anna—“

“What!?!”

“I’m starting to get mad…”

We spent the rest of the trip to the grocery store in silence. After we’d found a parking space, I handed the girl a coin and asked her to go get a cart.

I’d opened the trunk and was preparing to transfer our bags and bins when Anna returned, parking the cart next to the car.

“Mama,” she says, her face pink from crying and bashful. “Can I have a hug?”

And I didn’t need the Internet to tell me that this was submissive behaviour. That she was trying to apologize for shouting at me and for pouting before that.

But the difference between Anna and Kitty and even the neighbourhood dogs of my childhood is that my relationship with my daughter is slippery; we are both alternately dominant and submissive. More than that, we are just people, trying to get along, even if I built her in my body, cell by cell, limb by limb.

“Yes,” I say. And I pull her close, holding her tighter than usual. I want her to remember that once neither of us could remember where she began and I ended. I want her to hear my heartbeat, thudding irrationally in my chest.

And I am suddenly glad we are here, damp and irritable, in this parking lot, that we have all made it this far. My daughter was born in the hospital; Kitty was born under somebody’s stairs. But we love each other, and we most of the time, we remember to pull our claws.

Ariel Gordon is a Winnipeg writer. Her second collection of poetry, Stowaways (Palimpsest Press), won the 2015 Lansdowne Prize for Poetry. She is currently working on CNF about Winnipeg’s urban forest, which is slated for publication in 2018.

May 5, 2016

CanLit Gets Name Therapy

Anne-with-an-E, Booky, Dustan, Daisy Stone Goodwill, Zenia, Aminata, and more…

Anne-with-an-E, Booky, Dustan, Daisy Stone Goodwill, Zenia, Aminata, and more…

Inspired by Duana Taha’s book, The Name Therapist, I’ve made a list of the most storied names in Canadian literature. I had the most ridiculous fun writing this post, and really could have written it forever and ever.

May 4, 2016

No big scheme

It’s interesting to me how social media has changed the way I blog. I use Twitter to share other people’s stories, whereas I used to collect these in link round-ups here, and Instagram to capture moments of domestic mundanity thereby rendering them a little less mundane (which is arguable, of course. And I still take care to keep it pretty mundane around here too). Instagram is also a good place to tell my own stories, but it takes me ages to type on my phone so I do less of this. An exception is the story of slut sign, which I shared last night, but it got a really nice response. Anyway, maybe it’s clearer to say that social media hasn’t changed the way I blog, it just has had me spreading my blogging wider, across platforms. Twitter, Instagram, Facebook—it’s blogging, all of it. (But what about Snapchat? I don’t know. A blogger can only spread herself so wide.)

It’s interesting to me how social media has changed the way I blog. I use Twitter to share other people’s stories, whereas I used to collect these in link round-ups here, and Instagram to capture moments of domestic mundanity thereby rendering them a little less mundane (which is arguable, of course. And I still take care to keep it pretty mundane around here too). Instagram is also a good place to tell my own stories, but it takes me ages to type on my phone so I do less of this. An exception is the story of slut sign, which I shared last night, but it got a really nice response. Anyway, maybe it’s clearer to say that social media hasn’t changed the way I blog, it just has had me spreading my blogging wider, across platforms. Twitter, Instagram, Facebook—it’s blogging, all of it. (But what about Snapchat? I don’t know. A blogger can only spread herself so wide.)

Which brings me to this article about the end of the blog, Bookslut, which was one of the first book blogs I read years ago when my blog wasn’t a book blog and I could only dream of such a thing, along with other bloggers like Lizzie Skurnick and Maud Newton. The interview is so candid, smart and pointed, and embodies so many of my own ideas about blogging and its inherent wildness (and messiness!) and the fact that blogs and making money were never ever compatible (and that if you’re making money with your blog, it’s probably ceased to be a blog) and that blogging in search of a book deal is a sad sad pursuit and an insult to the form.

Anyway, I already shared the article on Twitter, but I want to share it here too, along with some of my favourite bits:

- “Well, the only reason why Bookslut was interesting was because it didn’t make money, and when I realized the sacrifices I was going to have to make in order for it to make money, it wasn’t worth it.”

- ” There was no big idea, no big scheme. I just wanted to talk about books with my friends.”

- “There’s always space to do whatever you want. You won’t get as much attention, but fuck attention. Fight for integrity.”

May 4, 2016

Flannery, by Lisa Moore

There was little doubt in my mind that Lisa Moore could pull off a YA novel. I remember her teen character in Alligator, which was a book that just delighted me when I read it first, and the vividness of her point of view. And as a writer who so skillfully employs word as tools to create meaning, I was sure she had the deftness to tune her work to a different kind of reader. Which, of course, didn’t preclude me from reading it too. If she wrote One Direction fan fiction, I’d probably read that as well. Lisa Moore’s name is a literary hallmark.

There was little doubt in my mind that Lisa Moore could pull off a YA novel. I remember her teen character in Alligator, which was a book that just delighted me when I read it first, and the vividness of her point of view. And as a writer who so skillfully employs word as tools to create meaning, I was sure she had the deftness to tune her work to a different kind of reader. Which, of course, didn’t preclude me from reading it too. If she wrote One Direction fan fiction, I’d probably read that as well. Lisa Moore’s name is a literary hallmark.

So it’s no surprised that I really enjoyed Flannery, her latest book. The title character is a sixteen-year-old girl whose best friend has started ditching her for her cool musician (and slightly dangerous) boyfriend. Meanwhile, Flannery has got to complete an entrepreneurship project with her partner Tyrone, who she’s known since they were babies and is quite possibly in love with, but he’s not showing up to do any work, plus her free-spirited artist mother can’t afford to buy Flannery the new biology textbook she’s required to have, and keeps writing about Flannery on her parenting blog, which other kids at school are actually reading.

Flannery’s voice and point of view represents a stable force in a crazy world, and she’s an amazing mix of confusion, steadfastness and yearning. And naturally, I was very interested in her mother’s character, which Moore renders with just as much nuance. I think a lot about a mother’s right to tell her own story, even when her child is part of that story, because suggesting otherwise is another way of telling a woman to shut up. I do think that when a mother writes about her child with a great deal of thought, she can do this successfully, although Moore shows that Flannery’s mother Miranda is not too thoughtful about her blog (which disappointed me a bit—I would have loved some substance here), or anything, for that matter. Except her love for her children, of course, which is demonstrated in lovely, pointed ways—Miranda swooping in to exalt Flannery’s entrepreneurship project, her intuition regarding the well-being of her son, which her smartass daughter doesn’t give her credit for. Moore shows the the imperfect mother is the only kind of mother, and sometimes that all a child needs.

But of course none of this would be of much concern to the novel’s target readers, for whom Miranda would only be peripheral, I think. Those readers will be just as wrapt as I was by the story though, by Flannery’s incredible outlook on the world, but menacing shadows at its edges. And yes, there is edge here, real significant danger, and Moore so successful melds these points into a true, believable life, rather than using them for more sensational purposes (as bad YA novels might do, and even as a very good one like Raziel Reid’s When Everything Feels Like the Movies did quite deliberately). As the world’s is, the emotional spectrum of Flannery is wide. There is a scene in a mall food court where Flannery is betrayed by Tyrone that will break your heart as profoundly as that scene did in Moore’s February when her character waits in a bar for a date who never arrives.

Moore doesn’t push syntax and narrative structure quite as hard in Flannery as she does in her other books, which is the one significant way that the book is a break from her oeuvre. But here and there in her prose sparkles in just the same way her readers have come to expect: “The sun was so low that its reflection was a perfect bright red circle on the water’s surface and as the boat swing around, the circle was smashed into a thousand pieces that skittered away from each other and then floated back together, making the perfect circle again.” Such an extraordinary sentence! And what a gift to any reader, regardless of their age.

May 2, 2016

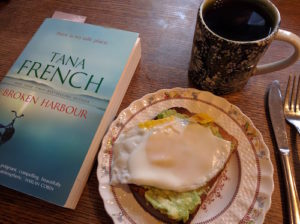

Tana French is Ruining My Life

I’ve been working my way through the works of Tana French ever since my friend Nathalie delivered all of her books to my house on New Years Day in a Waitrose bag, along with a container of soup. (Remember December, when everybody was sick?) Now usually such a loan would constitute a kind of imposition, but I’d been meaning to get into Tana French, and as soon as I opened the first book (In the Woods), I was hooked: “What I warn you to remember is that I am a detective. Our relationship with truth is fundamental but cracked, refracted confusingly like fragmented glass. It is the core of our careers, the endgame of every move we make, and we pursue it with strategies painstakingly constructed of lies and concealment and every variation on deception…”

I’ve been working my way through the works of Tana French ever since my friend Nathalie delivered all of her books to my house on New Years Day in a Waitrose bag, along with a container of soup. (Remember December, when everybody was sick?) Now usually such a loan would constitute a kind of imposition, but I’d been meaning to get into Tana French, and as soon as I opened the first book (In the Woods), I was hooked: “What I warn you to remember is that I am a detective. Our relationship with truth is fundamental but cracked, refracted confusingly like fragmented glass. It is the core of our careers, the endgame of every move we make, and we pursue it with strategies painstakingly constructed of lies and concealment and every variation on deception…”

And this is what’s most compelling about French’s novels, the slipperiness of her first person narrators, how they’re always just clinging to the edges of things, and totally unconscious of how close they are to falling. The subtlety with which she reveals the true circumstances behind her narrator’s carefully constructed reality, the skilful way she manages to reveal all the things these characters would never, ever tell us. The things these characters don’t even properly know themselves.

I’m reading her fourth novel now, Broken Harbour. (One more title to go before I return the Waitrose bag, and then French has a new novel coming out this fall. And then I fear it’s going to be like Harriet and Amulet, the way she went through the whole series, 1-7, boom boom boom, having no idea that Amulets don’t grow on trees, thinking new ones were an ever-available resource, and now she has to wait an eternity for number 8). And the book is kind of ruining my life, because I can’t stop reading it, staying up far too late and just-one-more-chapter. Because how can I not want to know what happens next?

Both my children are currently undergoing sleep changes and bed experiments and we’re all playing musical beds at our house these days, and the last few nights I’ve been awakened twice or three times before dawn. But I really can’t blame my current stupor on this entirely, on my children. Because the real reason I’m so tired, like words-confusingly tired, should-not-be-permitted-to-operate-a-motor-vehicle tired, is that I’m staying up past midnight reading Tana French, and then even once I manage to put the book down and turn the light off, I’m still immersed in its atmosphere, fearing shadows in the darkness. Awake and lying still, alert to barely perceptible sounds. Perhaps imagined ones. And the distinction doesn’t even matter.

May 1, 2016

The M Word: Ever Since The End, by Christa Couture

This is the fifth in a series of posts catching up writers from The M Word, and finding out what they’re up to now. (Find out more about The M Word and read its rave reviews right here.) From previous weeks: “Kerry Ryan on Wishing and Washing“; “Heather Birrell on Talking to her (M)Other Self”; “Dear Me, by Nicole Dixon“; “Kerry Clare on Motherhood and Abortion.”

In her essay, “These Are My Children”, Christa Couture introduces readers to her sons, Emmett and Ford, and recounts how she has mothered and related to motherhood since their deaths. Here, she considers what’s changed and what hasn’t in the two years since her essay was published.

*****

Between the time I first wrote “These Are My Children” and the time for final edits before The M Word went to print, the one update I made was to the ages my children would have been, if they were still alive (from six and three to seven and four).

I’m thinking of what’s changed in the time from print to now, and the same update is my first thought: Emmett would be nine, and Ford would be, in a few weeks from now, seven.

When asked to consider what else has changed in this time, I worried that nothing has. Motherhood remains a kind of fixed story for me, one I can still replay from its beginning to end. “The End” was the title of the final blog post where my husband and I kept family and friends updated on Ford’s 14 months of life while he was living. And when I think of my story with my children, “the end” feels almost like the title, not just the last page. I picture it a finished book; I picture that book in a bag that I carry forward into each year of my life.

That hasn’t changed.

I have moved from the city (Vancouver) where my sons’ ashes are interred to Toronto. Thus, I visit that site now, so far, only yearly. When I do, I still place my hand on the shared gravestone, still trace the letters, and still feel comfort in close proximity to their remains, and to the part of my body there.

That hasn’t changed.

When I return to their grave, new gifts have been left on its ledge, from their grandmothers, aunts, father… slow changes to the scenery take place.

In my essay, I had written of the physical record of my children on my own body. The stretch-marked belly remains the same, but the caesarean scar I’ve found comfort in tracing is almost entirely, to the eye, gone, and increasingly fading to the touch. As it fades, the whisper of the ridge of that scar gets quieter: “I am the window he climbed through, into your arms.”

I don’t mind that this fades. And that is a change.

I no longer, as I had written those few years ago, cry daily for them. When I do cry, it is with less distress.

With as much longing, but less panic. This change I am grateful for.

My therapist and I disagreed: he drew a chart, an arc, of grief and pointed to the end, “When is this?”

“Never.”

I argued I will always grieve for my children. He argued it’s an emotion that, like other emotions and like scars, will run its course and fade.

I don’t consider grief negatively. It has slowly become integrated in my body and life, blooming sometimes unexpectedly and otherwise reliably on certain holidays and anniversaries of death and birthdays. Sometimes grief still hurts enough that I gasp for air. Less often, grief still curls me into a ball and I feel blind to anything outside of it. Otherwise, it moves into my chest as a wave and with my hand to my heart and a deep breath, I sway with it until the intensity passes.

I understand better that the intensity passes.

That is a change.

A friend’s baby recently died and I realized that while I knew many bereaved parents, I had met them all after one or both of my sons’ deaths. I had not known it to happen to someone I already knew. I was struck in considering the beginning of what will be a very long journey and in remembering how impossible the first night feels. The first night is the worst one. And then the first week, the first month… how slow and dark time is until the first year when counting starts to become harder to do. How I ached, in early days, for time to pass yet hated that it did—that each day passing only took me further away from my children, putting that event and title “the end” further in the past.

“It’s not that it gets easier, but it does change,” I told this friend, knowing too well that there was nothing I could say that would help.

With her son’s death, I was reminded of having “entered a place in which I could be seen only by those who were themselves recently bereaved,” as described by Joan Didion in The Year of Magical Thinking. I felt, when I first saw my friend, seen in a way I seldom do. I found it comforting, a relief almost, for that part of me that remains hidden (against its need), and then immediately I felt regret: I would rather be lonely in grief considering that understanding can only come through such utter heartbreak.

And, in looking at a beginning after an end, I felt relieved for time passing.

“What place do you go to for strength?” I was recently asked. If time passing is a place, then that is where I have been since I first wrote my essay. I have been writing and singing and crying and moving across the country, and waiting.

And life has changed.

My boys would be nine and seven. I will always count those years and, occasionally, imagine who my boys would be, and would have become.

I will miss them. I will love them.

And that will never change.

**

Christa Couture’s new album is Long Time Leaving. It’s out right now. (Buy it!) She’s currently on a cross-Canada tour.