May 22, 2016

I slept all night

I slept all night last night. This is beginning to be kind of unremarkable, since I don’t know when, and it’s not always the case, but more and more it is. Which means something in particular right now, because I’m thinking back to the May holiday weekend last year, which was dreadful, and I wasn’t sure how it wasn’t always going to be that way. (That was the weekend where we had to send our babysitter home because Iris wouldn’t go to sleep, and taking 2+ hours to fall asleep in the evening would proceed to wake up at midnight and every few hours thereafter, and I was so tired and sad and felt enslaved by it all. That was the weekend I finally stopped breastfeeding and we left her to cry until she learned to fall asleep on her own, because I just couldn’t stand it anymore). And while it’s true that me daring to write this down here means that Iris will make up screaming at 4:30am tonight, it’s just nice to affirm that some things do get better.

We have had a nice weekend—we went to see my parents yesterday and drove home into the most stunning sunset and nobody cried or threw up because we’d gotten all that out of our system on the journey there that morning. Today we got up early (isn’t it funny what can happen when you sleep) and tidied up our backyard and deck for summer, planting flowers in our pots and getting them up all lined up on the fire-escape. Iris went down for her nap (because yes, Iris naps again—we found out that we like her so much better when she does) and I spent the afternoon drinking ice-tea in my hammock in the sunshine. And then got to work preparing for our party tomorrow—Victoria sponge cake and edible bunting (I KNOW!). It’s Harriet’s birthday party, which has a Queen Victoria tea party theme. There will be jam tarts and tiny sandwiches, and we will be making tea blends and decorating mugs. And the party launches our month of celebrations: her actual party on Thursday, Iris’s birthday not long after, and our wedding anniversary, and Father’s Day, and my birthday, and also the birthdays of both our moms. June is full to bursting. And goes by oh so fast.

I’ve been reading the most fantastic books this weekend—The Turner House, by Angela Flournoy, was a stunner of a debut novel, and one of the best books I’ve read in ages. I remember how good it felt to read The Corrections the first time all those years ago, back before hating Jonathan Franzen became an international pastime (who I’ve resented ever since Freedom), and The Turner House was kind of like that. The Detroit setting is so compelling, and the novel is so much in its reach (as any novel about a family with 13 siblings would be) and I loved it. I wanted to buy the book as soon as I read Doree Shafrir’s profile, “Why American is Ready for Novelist Angela Flournoy” and the novel did not disappoint. (Incidentally, how much richer would literature be if everyone wrote as wonderfully about books as Shafrir does here?)

I’ve spent today reading Double Teenage, by Joni Murphy, which I was initially concerned I wasn’t cool enough to appreciate, but it’s painful and wonderful (and is also the reason we’ve been listening to Graceland all day). The Katherine Lawrence book, Never Mind, is for our book club meeting next month. And yesterday I bought Modern Lovers, by Emma Straub, whose The Vacationers I read over the July 1 long weekend two years ago as I was embarking upon the first few pages of the first draft of Mitzi Bytes, and gave me the idea of the literary tone I aspired to. So I find myself nostalgic again as I contemplate her latest title while in the very early stages of a new writing project of my own. I kind of want to start reading it right away, but I also am tempted to save it, to look forward to it for a little longer.

May 20, 2016

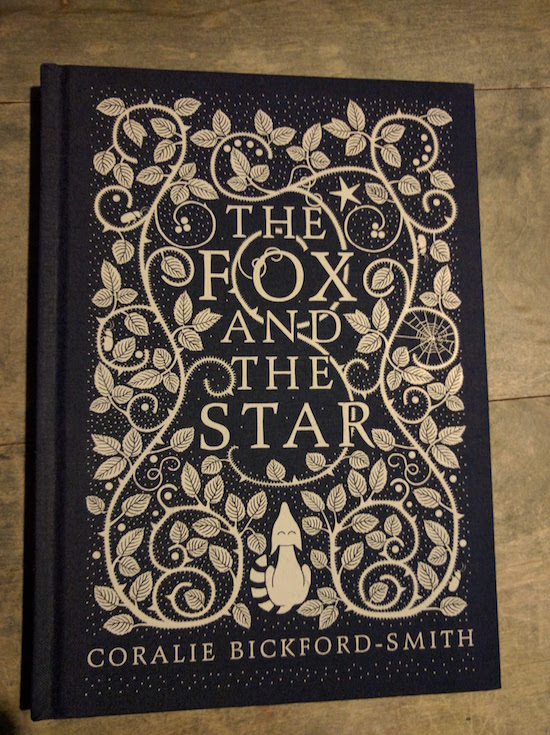

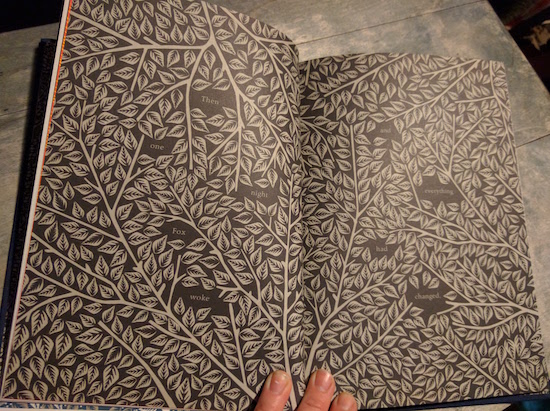

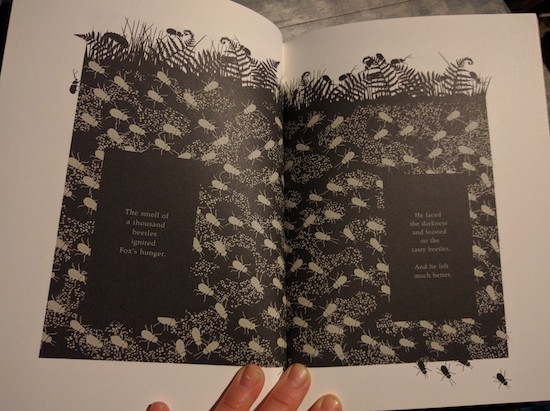

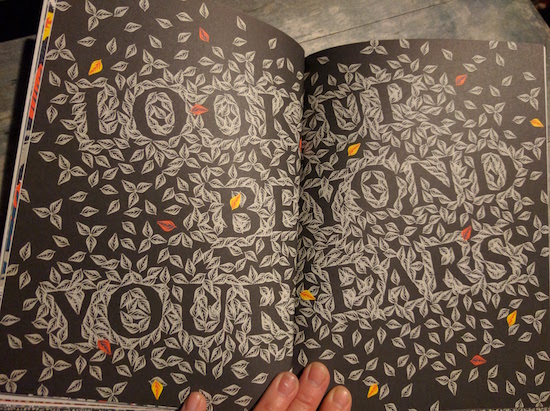

The Fox and the Star, by Coralie Bickford-Smith

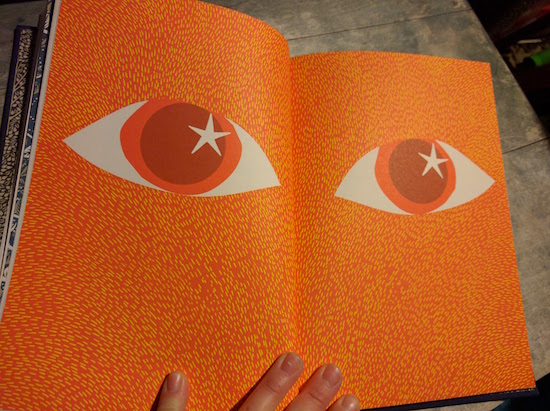

So obviously we didn’t end up buying The Dead Bird by Margaret Wise Brown, and got The Fox and the Star, by Coralie Bickford-Smith, which I can’t say is a hardship. And really, that this book is by Coralie Bickford-Smith (world-renowned book designer) tells you everything you need to know about The Fox and the Star: visually, the book is stunning. But does being a book designer necessarily mean that a person can write a book? In the case of Bickford-Smith, it does, in particular because design is so integral to what makes a good picture book work. I’m thinking of an author/illustrator like Virginia Lee-Burton who, like Bickford-Smith, knows the limits of the page and uses those limits and the liminal spaces. There is no single part of the book that doesn’t matter, that doesn’t have attention to it.

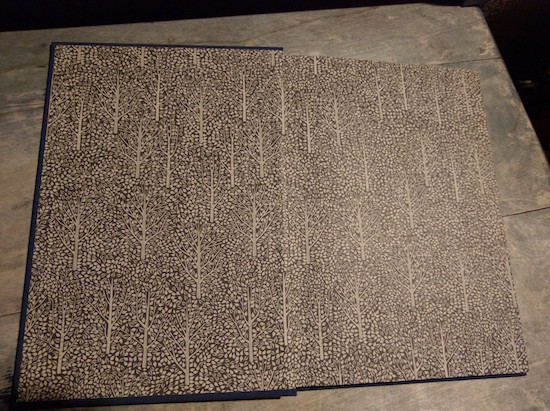

Can in point? Endpapers.

The Fox and the Star is the story of a fox who is small beneath the trees and the sky, but takes comfort in the constancy of a star above him.

The forest is not the the place for constancy though, and one night the fox looks above him and the star isn’t there anymore.

Bickford-Smith shows the life and movement of the forests, above ground, on the ground and underneath it. Her scurrying insects are amazing, as our the rabbits created of white space, and the ferns, and the orange of the leaves as the seasons change, and how she integrates the text into her illustrations. And gradually we begin to understand what has happened to the star.

And as the leaves fall, the fox looks up to find the star again, high up in a sky that’s full of them: “Fox could not believe there were so many stars. His heart was full of happiness.”

This book is exquisite.

May 19, 2016

The Suitcase

On Friday night we watched “The Suitcase”, which might be my very favourite episode of Mad Men ever (along with “The Wheel”, “Shut the Door, Have a Seat,” “Meditations in an Emergency,” and and and…). Although it’s significant to note that it’s taken us three months to get to “The Suitcase” after (re)watching the first three seasons at almost an episode daily throughout January and February. Part of this is circumstantial: we went away for the first week in March, we spent some time watching other things (including a Mad Men-inspired viewing of The Apartment, which was so wonderful), and I also stopped watching TV daily because I wanted time to read. But part of it is also the nature of Season 4, which was a turning point for the series. It was always Don Draper’s domestic situation that interested me most about the show—the contradiction of his character trying to fit the mould of husband and father—and by Season 4 that situation has disintegrated. (He eventually gets together with Megan, but their relationship never mattered to me as much as Don and Betty’s did, partly because it was hard to believe it really mattered to either of them. The stakes were never high enough.) Season 4 is also painful to watch in places—Don Draper is falling to pieces. It makes me think about the freedom Don is promised by the end of his marriage, which sounds like what he was sold as a child in “The Hobo Code” about being able to sleep so much better without the chains of a mortgage, etc. But it doesn’t turn out to be so freeing after all.

But with “The Suitcase,” Season 4 finally starts to get it together, just like Don does. It’s a pivotal episode for Peggy as well, who finally breaks up with her mediocre boyfriend and begins to see herself on equal terms with her boss. (Remember back in Season 2 where she calls him “Don” for the first time? It’s like that.) We see the depth of Don’s descent in this episode too, which we’ve only glimpsed in previous ones. He’s gross, and ugly, and mean. But he also makes himself known here in a way he doesn’t very often. At no point in this episode did I have to write, “What is Don Draper thinking?” in my notes is what I mean, and I always have to write that. When Peggy suggests that Anna is not the only person in the world who knows Don, she’s not wrong. She doesn’t know the details, but she gets him. She knows what he’s thinking, and she takes her knowledge to apply to her own situation to get where she’s going. But in this situation also, she can use it to be a friend. (And neither of these characters has very many of these.)

The episode is also really funny, delivering that legendary scene in which Duck Phillips tries to take a shit in Roger’s chair. “I killed 17 men at Okinawa.” Fantastic bathroom scenes too—Megan and Peggy, and then a heavily-pregnant Trudy Campbell and assures Peggy that she’s still young. (Also, “You’re witty…) And then the look on Pete’s face when he sees Peggy and Trudy together. They are a fascinating triumvirate. We find out Peggy’s resentment at Don taking all the credit for the GloCoat ad: “You never say thank you.” “That’s what the money is for.” They go out to eat and Don asks Peggy, “What’s the most exciting thing about a suitcase?” “Going somewhere,” she answers. They talk about how you know when you’ve had a good idea. Coming back to the question of wanting and desire, which has been a fixation of the series from the start. “I know what I’m supposed to want, but it never feels right,” says Peggy, articulating something that Don has never been able to do, but certainly understands.

They talk about how they both saw their fathers die. Don reveals that he never knew his mother. He tells Peggy that she’ll find someone, “You’re cute as hell,” and she tells him that everybody thinks she got her position by sleeping with him. He says that he didn’t sleep with her because she was unattractive, but because he has rules for work. She reminds him that he’s broken those rules. “You don’t want to start giving me morality lessons,” he tells her. “People do things.” And then he asks her about her baby—do you know how strange this is? For Don to be curious about anybody’s inner life? (I wonder if there is a connection between the mother he lost and the baby Peggy gave away.) “Do you think about it?” he asks her. She tells him, “It comes out of nowhere.”

They talk about how they both saw their fathers die. Don reveals that he never knew his mother. He tells Peggy that she’ll find someone, “You’re cute as hell,” and she tells him that everybody thinks she got her position by sleeping with him. He says that he didn’t sleep with her because she was unattractive, but because he has rules for work. She reminds him that he’s broken those rules. “You don’t want to start giving me morality lessons,” he tells her. “People do things.” And then he asks her about her baby—do you know how strange this is? For Don to be curious about anybody’s inner life? (I wonder if there is a connection between the mother he lost and the baby Peggy gave away.) “Do you think about it?” he asks her. She tells him, “It comes out of nowhere.”

And then when Don calls Stephanie and gets the news that Anna has died, and he falls apart, and they sleep together, but only in the literal sense. And then she returns to his office later that morning and he’s all fresh as though nothing has happened, and she’s gone to sleep on her office couch, and we’re all ready to see him punish her for having witnessed his vulnerability—it’s certainly happened before. But he doesn’t. And how he how he clutches her hand. All this anticipating the wonderful episode in Season Six (or Seven?) when they dance together. And also referring back to when she stroked his hand provocatively in the first episode of the series and he rejected her (and I suppose also how he takes Betty’s hand when she tells him she is pregnant at the end of Season 2—interesting how a man supposedly so fluent in ideas is most honest with a wordless gesture).

When she leaves the room, the door is left open. And Don Draper is ready to start climbing again.

May 18, 2016

Mini Reviews: He Wants and Middenrammers

Alison Moore follows up her Booker-shortlisted The Lighthouse with He Wants, a novel that is an exercise in withholding and revelation. As the title suggests, this is a book about yearning. Lewis Sullivan has lived a quiet life and cannot articulate just what he longs for to either himself or to his reader, although the reader going back through the seemingly quiet text will notice that all the signs are there, in previously invisible flashing lights, even, and it’s quite remarkable that a “quiet” text can be such a minefield upon rereading. The narrative follows Lewis over the course of a single day whose pattern is disturbed by the arrival of a stranger in town…except that he’s not a stranger at all, but Lewis’s former schoolmate. And while the novel’s web became too tangled by the end—story threads about Lewis’s daughter and also a local thug distracted from the central story, too much coincidence—the climax is perfectly, subtly performed, and beautifully written. DH Lawrence fans in particular should take note. Plus, Rachel Cusk loved it.

Alison Moore follows up her Booker-shortlisted The Lighthouse with He Wants, a novel that is an exercise in withholding and revelation. As the title suggests, this is a book about yearning. Lewis Sullivan has lived a quiet life and cannot articulate just what he longs for to either himself or to his reader, although the reader going back through the seemingly quiet text will notice that all the signs are there, in previously invisible flashing lights, even, and it’s quite remarkable that a “quiet” text can be such a minefield upon rereading. The narrative follows Lewis over the course of a single day whose pattern is disturbed by the arrival of a stranger in town…except that he’s not a stranger at all, but Lewis’s former schoolmate. And while the novel’s web became too tangled by the end—story threads about Lewis’s daughter and also a local thug distracted from the central story, too much coincidence—the climax is perfectly, subtly performed, and beautifully written. DH Lawrence fans in particular should take note. Plus, Rachel Cusk loved it.

**

John Bart’s debut novel, The Middenrammers, suffers from being a novel with a political agenda, which works in places to undermine the impact of the characters on the page who are not necessarily enlivened by their own will. It’s the story of a young doctor who arrives in a Yorkshire town to practice at the town’s maternity hospital in 1970, and finds himself up against forces working to restrict women’s access to contraception and abortion. Things are a little too black and white—the evil-doers in this book are so totally evil but—as Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie wrote in her novel, Americanah—“like life is always fucking subtle.” And whenever I was feeling frustrated by the lack of subtlety, Bart would go and blow me away with a stunning scene, like the one in which the doctor has his arm stuck inside a woman’s vagina to keep the cord from prolapsing, and must move through the entire hospital in this awkward manner to get her to surgery. And he portrays the devastating impact of restricting women’s reproductive freedom, and shows too how such restrictions are part of systemic project of oppression of women and the poor. Despite my few reservations, I really enjoyed this fast paced novel, read it in a day, and think it would appeal to anyone who’s been a fan of Call The Midwife.

John Bart’s debut novel, The Middenrammers, suffers from being a novel with a political agenda, which works in places to undermine the impact of the characters on the page who are not necessarily enlivened by their own will. It’s the story of a young doctor who arrives in a Yorkshire town to practice at the town’s maternity hospital in 1970, and finds himself up against forces working to restrict women’s access to contraception and abortion. Things are a little too black and white—the evil-doers in this book are so totally evil but—as Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie wrote in her novel, Americanah—“like life is always fucking subtle.” And whenever I was feeling frustrated by the lack of subtlety, Bart would go and blow me away with a stunning scene, like the one in which the doctor has his arm stuck inside a woman’s vagina to keep the cord from prolapsing, and must move through the entire hospital in this awkward manner to get her to surgery. And he portrays the devastating impact of restricting women’s reproductive freedom, and shows too how such restrictions are part of systemic project of oppression of women and the poor. Despite my few reservations, I really enjoyed this fast paced novel, read it in a day, and think it would appeal to anyone who’s been a fan of Call The Midwife.

May 17, 2016

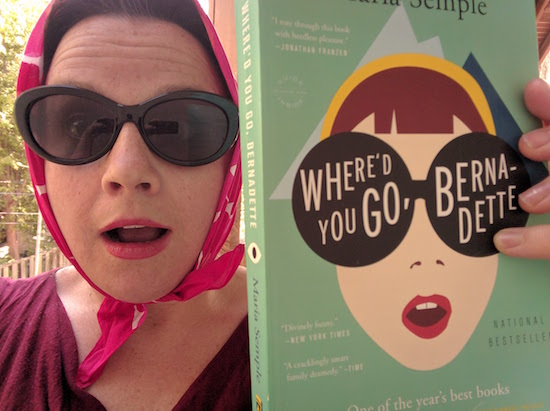

New Maria Semple!!!

I really am this excited about the news of a new book by Maria Semple coming this fall. You can learn more about it and also read an excerpt here. (Yay!!!) Today Will Be Different is out in October.

May 16, 2016

How to Terrorize Your Child with Margaret Wise Brown

We were at the bookstore a few weeks ago, and I couldn’t narrow down my selection of picture books.

We were at the bookstore a few weeks ago, and I couldn’t narrow down my selection of picture books.

“Should we get,” I proposed to Harriet, “The Fox and the Star, by Coralie Bickford-Smith, or The Dead Bird, by Margaret Wise Brown.” I was emphatically waving the latter in the air.

Harriet pointed to the other one. “Why would I want to read a book about a dead bird?”

“Only because it’s a reissued book by a literary icon that dares to confront uncomfortable issues of mortality.”

“No,” she said.

I said, “Why?”

She said, “I don’t want to read books about dead things.”

She was still annoyed about a recent book I’d read her in which the Grim Reaper comes to tea and takes away the children’s grandmother, and everybody understands and feels good about the whole thing. Even though the children appear to left without a guardian. And even though the book doesn’t address the question of death coming for children, or young parents—would we put the kettle on for the reaper then? Though if someone wrote that book, I’d probably make Harriet read it too.

“So we’re getting The Dead Bird,” I told her. The illustrations are beautiful—by the award-winning illustrator of Last Stop On Market Street— and normalizing death is healthy and wasn’t there a dead bird in Sidewalk Flowers by Jon-Arno Lawson and Sydney Smith? And everybody liked that book.

And Harriet said, “No.”

“The Dead Bird,” I said.

She said, “No dead bird.” And she seemed kind of immoveable, so I didn’t want to push it.

Two weeks later, we were at the library and I saw The Dead Bird on the new releases shelf.

“Now isn’t that lucky,” I said. “A brand new copy of The Dead Bird, and nobody else has picked it up yet. It must be fate. The book was meant for us.”

“Do you think nobody has picked it up,” said Harriet, “because nobody would ever, ever want to read it?”

But I pooh-poohed her. Dropped the book into our library bag. A red-letter day—we’d brought The Dead Bird Home. What a find!

I told her, “I can’t wait to read this.”

She said, “I can.”

I told her, “Just wait. It’s about death. And dying! Come on, you’re going to like it.”

“I won’t,” she said.

I said, “You’ll see.”

Today I told her, “I’m writing a blog post about you reading The Dead Bird.”

She said, “I’m still not going to read it.”

“But how am I going to write the blog post if you don’t?

She told me, “I read it already, actually. By myself.”

“And did you like it?”

She said, “No. It’s about a dead bird. What’s to like?”

I admitted to her, “You know, the New York Times Book Review shares your assessment of it. And of the Grim Reaper book also.”

She said, “I told you.”

I said to her, “Who are you? Are you even my child? Ursula Nordstrom would be rolling in her grave if she could hear you right now.”

And she said, “Yeah. And then Margaret Wise Brown would go ahead and write a picture book about it. And then wouldn’t you like to go and try to make me read that too.”

“You’re not going to let me read you The Dead Bird then.”

And Harriet said, “No.”

May 15, 2016

A Pillow Book, by Suzanne Buffam

In the notes for Eula Biss’s On Immunity: An Inoculation, the author writes about the other mothers with whom she found herself “in constant conversation” after she became a mother herself, “and the subject of our conversation was often motherhood itself.” (My experience of these same conversations inspired a book, as I wrote about in my foreword here.) Biss writes, “These mothers helped me understand how expansive the questions raised by mothering really are.” And so it meant something to me that Eula Biss is one of the people acknowledged in A Pillow Book, by Suzanne Buffam (whose first book won the Gerald Lampert Prize and whose second was a finalist for the Griffin Prize), that Biss included Buffum in her own acknowledgements as one of the friends by whose conversations her own writing was fed, to consider that A Pillow Book was born of those conversations from the other side.

In the notes for Eula Biss’s On Immunity: An Inoculation, the author writes about the other mothers with whom she found herself “in constant conversation” after she became a mother herself, “and the subject of our conversation was often motherhood itself.” (My experience of these same conversations inspired a book, as I wrote about in my foreword here.) Biss writes, “These mothers helped me understand how expansive the questions raised by mothering really are.” And so it meant something to me that Eula Biss is one of the people acknowledged in A Pillow Book, by Suzanne Buffam (whose first book won the Gerald Lampert Prize and whose second was a finalist for the Griffin Prize), that Biss included Buffum in her own acknowledgements as one of the friends by whose conversations her own writing was fed, to consider that A Pillow Book was born of those conversations from the other side.

Although Buffam’s book is not obviously a companion to On Immunity. At first glance, it has more in common with Jenny Offill’s novel, Dept. of Speculation, a novel in fragments whose form suits the disintegration of the protagonist’s marriage, career and sense of self after she becomes a mother. The novel has been celebrated for its frankness in addressing that kind of disintegration, although my struggle with the book was with its failure to really be a novel. Whereas Buffam’s book is catalogued as poetry, and we’re told within the book itself (as well as on its back cover): “Not a memoir. Not an epic. Not an essay. Not a spell. Not a shopping list. Not a field report. Not a prayer. Not a dream book. Not a novel…” A far more interesting book for its lack of imposition of structural constraint.

While On Immunity is certainly apart from these, a volume of rigorous non-fiction, I think the three books form a fascinating trinity. When I am trying to persuade a reader to pick up Biss’s book (because not everyone is always up for rigorous non-fiction), I tell them that this is the kind of rigorous non-fiction a woman writes when she has a small child. It’s a short book, created of manageable pieces. You could pick up the book and read a section every time you feed your baby, is what I mean. So in a way while it’s decidedly coherent, On Immunity is structurally as fragmented as the others. Furthermore the whole premise is that Biss is trying to make sense of a world that has been exploded to pieces, to reconcile polarities and complexities, to put the pieces back together. Which is what Offill and Buffam are doing as well, and I wonder if together these books suggest a new genre of mother-lit, books that use structure and content to interrogate and complicate the narratives we’re handed about what motherhood is supposed to be and who mothers are and what we’re supposed to preoccupied with. All three books also blend autobiographical elements with fiction (or non-fiction in the case of Biss) in ways that further complicate the narrative and allow the author a necessary expansion of literary possibility.

(Sarah at Edge of Evening wrote this week about Her 37th Year: An Index, by Suzanne Scanlon, and after I read her post, I immediately ordered the book from the publisher. I have a suspicion that this book too might fit [but not comfortably; there are is nothing comfortable about these books] into the genre I’m talking about.)

Buffam’s collection has been born of a certain panic. The first: she’s unable to sleep. In lieu of counting sheep, she’s making lists, strange connections, pursuing fascinations, and becoming preoccupied with sleep hygiene. Plus pillows. “Among the oldest living pillows in the world today is a smooth block of unpainted wood with a wide crack running through its middle and a shallow indentation on the top,” the book begins. The next fragment of text starts, “F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote lists. Abraham Lincoln took midnight walks…. I put a piece of paper under my pillow at night, and when I could not sleep, I wrote in the dark, wrote Henry David Thoreau, who once spent a fortnight in a roofless cabin with his head on a pillow of bricks.”

Lists such as, “Books I’d Like to Read Someday,” “Dream Jobs” (the fragment above which is a piece beginning, “Later that fall in West Orange, New Jersey, Thomas Edison staged the first pillow fight ever recorded on film.”), “Unendurable” (“Dinner with donors./ Dreadlocks on a WASP.”), and “Dubious Doctors” (“Dr. Feelgood/ Dr. Doolittle/ Dr. Spock../Dr. Pepper./ Dr. Dre.”), “Moustaches A to Z” (Anwar Sedat and Burt Reynolds to Yosemite Sam and Zorba the Greek).

The fragments are divided by small circles whose shadings progress in the way of the lunar cycle (as in the cover of the book). And amidst all these other curiosities are dispatches (though “not a dispatch” is probably also true) from the field of motherhood, the narrator’s young daughter referred to as “Her Majesty:

“No luck with the potty today I record in my little blue pillow book. No interest, either, in wearing the new Hello Kitty underwear I bought last week at Target, though Her Majesty did kiss each pair as we removed them from the shiny plastic packaging.”

“Was Shonagon bored? Was she lonely?” Buffum’s narrator wonders of the Japanese author of the first Pillow Book, another object of fascination. We see her husband meeting with a student to discuss her paper on Spinoza: “From the hovering basket of a hot-air balloon in our front yard…the lift off into a swirling swarm of downy flakes, leaving me behind with Her Majesty in the kitchen…” Early in the book, moons before, she recalls sharing sushi “with a famous aging editor in New York.” When he learns she has no children (yet), he tells her, “Good…You’ll be finished as a writer if you do.”

As I said, this is a book that is born of panic.

And it’s fascinating, so readable. It got to the point where I had to put my bookmark onto the following page without turning it over because if I hadn’t, I would have read the page, devouring the whole book in a sitting, when it felt so good just to eke it out, a few pages before bedtime. A book truly to savour. Because the contents are so strange and interesting, ever surprising, and the language is beautiful. I kept reading parts out loud to my husband, and it was then that the poetry of the prose, Buffam’s attention to language was most clear, with subtle rhymes, alliteration. A sense of rhythm. A sense of humour most of all.

May 13, 2016

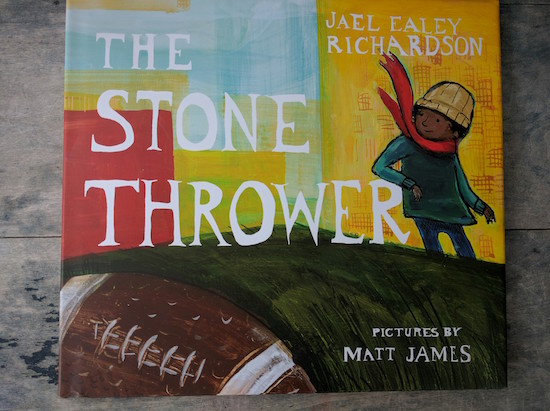

The Stone Thrower, by Jael Ealey Richardson and Matt James

Because this is the week that began with The Festival of Literary Diversity, it only seems fitting to end it with The Stone Thrower, a brand new picture book written by The FOLD’s executive director, Jael Ealey Richardson and illustrated by Matt James (of the award-winning I Know Here). Richardson has told the story before of how an impetus for the festival was her experience promoting her first book, a non-fiction biography of her father, CFL Quarterback Chuck Ealey, and having an indie bookstore owner decline her invitation to visit with the explanation, “This town is very white.”

“There are so many gatekeepers – publicists and sales reps, and bookstore owners, and all these people have to buy into the story in order for you to have any chance,” Richardson explained in her interview with Quill & Quire, and The FOLD emerged as part of an effort to find a way to change that. And now The Stone Thrower is the other creation that Richardson has brought into the world this spring, her father’s story told in picture book form, and it’s every bit as extraordinarily good.

The first time I finished reading this book to my children, we closed the cover a little bit breathless.

“That was really good,” said my oldest daughter, and we made sure to read the book again at night before bedtime so that her dad could know just what we were talking about.

He was also very impressed.

And what do I mean by the fact that this is a book that took our breath away? Because we read a lot of books. We know from good. But rare is the book like this one, with a moral tone as gripping as its story, full of suspense and ultimate triumph, spots of humour, rich and warm illustrations, and prose that feels wonderful in your mouth when you say it.

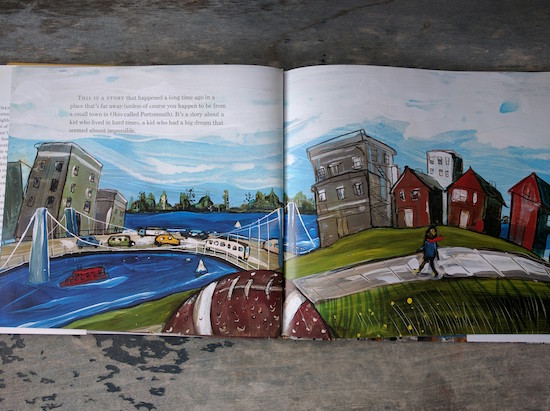

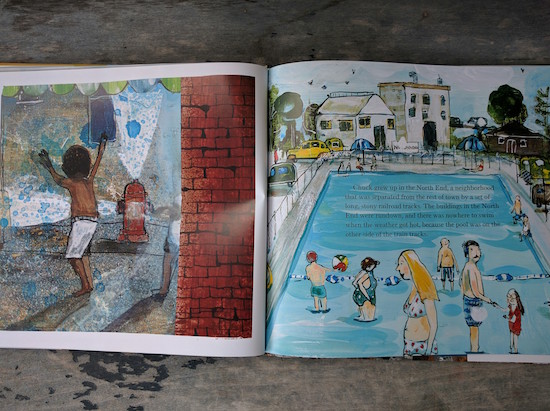

It is the story of a boy called Chuck who grew up in Portsmouth, Ohio, during the 1950s. “It’s a story about a kid who lived in hard times, a kind who had a big dream that seemed almost impossible.” And the odds are against Chuck, a Black kid growing up on what was literally the wrong side of tracks. James’ illustration shows Portsmouth’s white residents cooling off on summer days in a swimming pool, while the kids on the North End, like Chuck, played in the spray from opened-up fire hydrants. Chuck’s mom works hard, but she dropped out of school when she was young and makes very little money. She wants a different kind of life for her son.

“Those coal trains that come through, they don’t stop here,” she said. “I want you to be just like that. Do you remember where you’re going, son?”

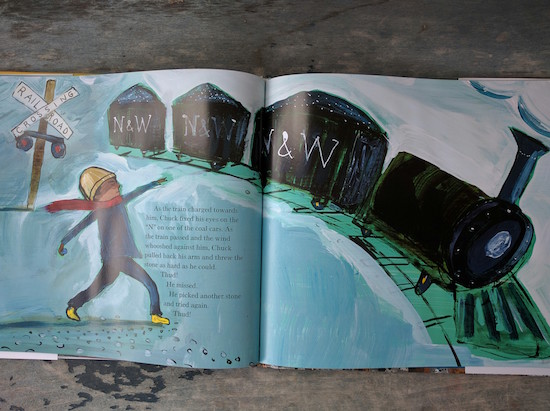

While walking down by the tracks, Chuck picks up a stone as the train comes by. Richardson makes her story rich with atmosphere: “The ground began to rumble, and the train tracks shook. The stones along the tracks jumped and bounced like hot kernels of popcorn.” Chuck aims for the N on the N&W on the boxcars (for Norfolk and Western), and throws. And misses. And misses again. But as the last car chugs by, he tries one more time: “BANG! Chuck smiled and raised his hands in victory.”

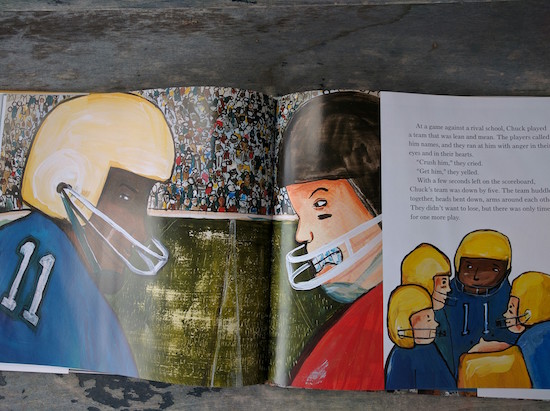

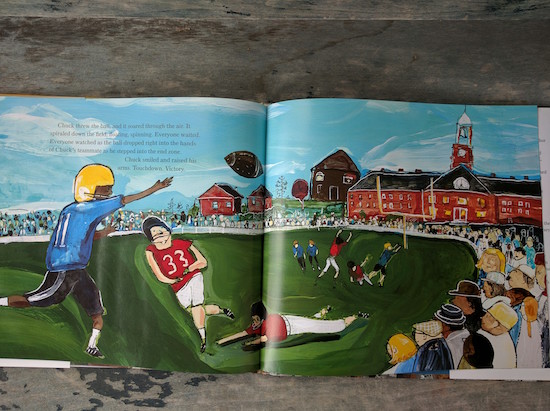

And this kind of persistence becomes emblematic of Chuck’s experience both in school and in football too, paving the way to his success as quarterback of the school football team. At games, he faces taunts from rival players because of the colour of his skin, but Chuck doesn’t let this break his focus from the object of the game, which is to connect with his teammates and win. And he does. The final words of the story: “Touchdown. Victory.”

The story is made all the more poignant with Richardson’s author’s note at the end of the book, which explains that Chuck Ealey won every game as quarterback of his high school team, and received a scholarship to the University of Toledo, where he won every game there. But after graduating with his college degree (“the best of all his victories”) he finds himself unable to play professional football in America, because the idea of a Black quarterback was still unfathomable to the powers that be.

So he moved to Canada, and played in the CFL, leading the Hamilton Tiger-Cats to the Grey Cup in his very first year. “It’s an unbeatable story that amazes me,” writes Richardson, “even though I’ve heard it all before, because Chuck Ealey happens to be my father.”

In Richardson’s Quill and Quire interview, Groundwood Books Publisher Sheila Barry underlines the need for more contemporary Black figures to inspire young kids: “We have Viola Desmond, but that was a long time ago.” Although obviously, this is a book that will appeal to readers regardless of the colour of their skin.

Together, Richardson and James have hit a target of their own: that of a really great story. And they totally nailed it.

May 12, 2016

Throwback Thursday

I was a compulsive photographer and documenter of days long before I’d ever heard of social media, although it’s true that I didn’t photograph my lunch back then. But it’s true that I used to take photos of everything and everybody, evidence of this being picture after people of lined up in a row looking awkward and confused about just why I am taking their pictures. People sitting around a table looking unimpressed seemed to be my primary focus as a photographer, although I think they’d been happy and engaged enough until I pulled my camera out, this being, of course, why I wanted to take the picture. To capture something. As if that was even possible, and it makes me things of the drawers in Joan Didion’s New York apartment in Blue Nights stuffed with envelopes and documents and things that she imagined could keep her from losing the people she loved. I have engaged with that book, in all its messiness and imperfections, in a way that I haven’t with The Year of Magical Thinking. I say “haven’t” because I imagine that I will some day, that like with Rachel Cusk’s A Life’s Work and motherhood, one day my universe will shatter and I will finally understand what Didion is talking about about. Not that I’m counting down to that. But I understand the impulses of Blue Nights so innately, and not just because it’s May and the nights are blue and we’re coming up to the solstice. And my urge to capture and keep everything that happened to me back in those days between the ages of 16 and 23, say, ultimately would come to nothing. It was always going to be like that.

I was a compulsive photographer and documenter of days long before I’d ever heard of social media, although it’s true that I didn’t photograph my lunch back then. But it’s true that I used to take photos of everything and everybody, evidence of this being picture after people of lined up in a row looking awkward and confused about just why I am taking their pictures. People sitting around a table looking unimpressed seemed to be my primary focus as a photographer, although I think they’d been happy and engaged enough until I pulled my camera out, this being, of course, why I wanted to take the picture. To capture something. As if that was even possible, and it makes me things of the drawers in Joan Didion’s New York apartment in Blue Nights stuffed with envelopes and documents and things that she imagined could keep her from losing the people she loved. I have engaged with that book, in all its messiness and imperfections, in a way that I haven’t with The Year of Magical Thinking. I say “haven’t” because I imagine that I will some day, that like with Rachel Cusk’s A Life’s Work and motherhood, one day my universe will shatter and I will finally understand what Didion is talking about about. Not that I’m counting down to that. But I understand the impulses of Blue Nights so innately, and not just because it’s May and the nights are blue and we’re coming up to the solstice. And my urge to capture and keep everything that happened to me back in those days between the ages of 16 and 23, say, ultimately would come to nothing. It was always going to be like that.

(For me everything hinges on 2002. I met my husband that year and stopped longing, and have been more or less happy ever since. Everything that ever happened before that year mostly mortifies me to consider now. And I wonder if I was able to shrug off my impulse to document it all and keep everything because from that point on I had someone with whom I could verify that all of these things actually happened. Another idea: that the internet took over my life that year and I started capturing everything online. And that I’m just as a compulsive a documenter as I ever was, and well, you’re kind of reading the evidence of that.)

The other night I had occasion to sort through my boxes of photographs upstairs. I have one from high school and the other from university. There used to be many, many more photographs, but I did a cull about a decade ago because there are only so many photos a person needs of her boyfriend from grade eleven, though I did not think so when I posed for those shots. And what I realized the other night as I was looking through photos from my university years is most of these photos signify nothing now. There are people I love and unbelievably bad haircuts, and I continue to be baffled by everything I ever wore. The decor of all of my bedrooms is also unfathomable: throughout those years I had either a Spice Girls or John Travolta as Vinnie Barbarino post above my bed at all times, plus inspirational quotes written in marker on index cards, an album cover with a picture of Nana Mouskouri on it, and a campaign poster for John F. Kennedy. It was kind of a weird aesthetic.

And maybe I knew it was always going to get lost. Perhaps it was never about capturing and keeping, but instead about evidence that any of it had ever been. That if it weren’t for the photos, I’d never believe in a room like that, and I’ve got the pictures and I still don’t. And I see my friends and I with our arms around our shoulders in rooms that I don’t recognize, places where I’m sure I’ve never been. There are people in those photos who mean nothing to me now. And there are holes in my memory as big as oceans—did you know that I saw Prince on stage with Sheryl Crow at the Lilith Fair in 1999? I didn’t. I still don’t, really. And even the stranger things, like the photo from my 22nd birthday party, me and three other people, and two of them are dead. Or that during the 2000/2001 school year, I lived in an apartment with a huge black and white photo of the New York City skyline at night hanging over the fireplace. The World Trade Centre, but I never even knew what those towers were called until five months after I’d moved out of there and into another apartment, until the towers were gone and we sat on our roof that night watching the CN Tower gone dark.

And maybe I knew it was always going to get lost. Perhaps it was never about capturing and keeping, but instead about evidence that any of it had ever been. That if it weren’t for the photos, I’d never believe in a room like that, and I’ve got the pictures and I still don’t. And I see my friends and I with our arms around our shoulders in rooms that I don’t recognize, places where I’m sure I’ve never been. There are people in those photos who mean nothing to me now. And there are holes in my memory as big as oceans—did you know that I saw Prince on stage with Sheryl Crow at the Lilith Fair in 1999? I didn’t. I still don’t, really. And even the stranger things, like the photo from my 22nd birthday party, me and three other people, and two of them are dead. Or that during the 2000/2001 school year, I lived in an apartment with a huge black and white photo of the New York City skyline at night hanging over the fireplace. The World Trade Centre, but I never even knew what those towers were called until five months after I’d moved out of there and into another apartment, until the towers were gone and we sat on our roof that night watching the CN Tower gone dark.

Maybe it’s not the photos that turned out to signify nothing that so fascinate me, but instead the ones that ended up telling stories so different from those I thought I was telling at the time.

May 11, 2016

13 Ways of Looking at a Fat Girl, by Mona Awad

I wasn’t expecting to struggle with Mona Awad’s debut, 13 Ways of Looking at a Fat Girl. The day I bought it, I met up with two friends who both happened to be in the middle of the book and they said it was great. It’s been receiving rave reviews. But as I began to read it, I couldn’t help but find it unsettling, and not just in the ways it was intended to unsettle. Part of the problem is entirely my own—I’ve had a hard time reading most of the books I’ve picked up in the last couple of weeks. Part of the problem too was with the book’s design, the unfinishedness of its stark design and its lack of heft. Was lack of heft the problem? Ironic. I did keep thinking that I’d read a version of this book a long time ago, and it had been called A Girls Guide to Hunting and Fishing. Was I being chick-lit-ist? But then Awad’s Elizabeth is definitely no “chick.” There’s nothing pink about this book. The only shoe you’d put on this cover would be an army boot, but maybe that was the trouble—Elizabeth the teen goth all in black, maudlin and sad. A bit like the actual cover then, rough outlines, scrawled. Maybe that was the problem too.

I wasn’t expecting to struggle with Mona Awad’s debut, 13 Ways of Looking at a Fat Girl. The day I bought it, I met up with two friends who both happened to be in the middle of the book and they said it was great. It’s been receiving rave reviews. But as I began to read it, I couldn’t help but find it unsettling, and not just in the ways it was intended to unsettle. Part of the problem is entirely my own—I’ve had a hard time reading most of the books I’ve picked up in the last couple of weeks. Part of the problem too was with the book’s design, the unfinishedness of its stark design and its lack of heft. Was lack of heft the problem? Ironic. I did keep thinking that I’d read a version of this book a long time ago, and it had been called A Girls Guide to Hunting and Fishing. Was I being chick-lit-ist? But then Awad’s Elizabeth is definitely no “chick.” There’s nothing pink about this book. The only shoe you’d put on this cover would be an army boot, but maybe that was the trouble—Elizabeth the teen goth all in black, maudlin and sad. A bit like the actual cover then, rough outlines, scrawled. Maybe that was the problem too.

My problem with 13 Ways of Looking Like a Fat Girl was one that interested me, which is vastly different from most books I have a problem with. The problem I have with most books is that they don’t interest me at all, but this wasn’t the case here. It was totally bizarre. Here I was getting hung about a book because its protagonist was so unlikeable—which says way more about me than that protagonist. What kind of a reader am I? Only the kind of reader who usually considers herself above such critical assessments. Unlikeable, piffle. But I couldn’t shake it here. Elizabeth, I wanted to say to the girl, cheer the fuck up. It can’t all be that bad. Wash off all that unfortunate eye makeup and go out into the sunshine.

Part of my problem with 13 Ways of Looking Like a Fat Girl was personal. In general terms, to be a woman is to be afflicted with a mild case of body dysmorphia, and this inability to grasp one’s own bodily reality for me hasn’t been aided by the three times I’ve lost about 30 pounds in the last 20 years (only once through trying really hard; there was also the time I moved to Japan and the other when I stopped breastfeeding) or the two times I’ve gained 30 pounds in pregnancy, not to mention the other times I’ve gained 30 pounds without any real explanation (except for that one time, which was all down to moving to England, eating a lot of sausage [not a metaphor, you sick dog] and being in love). So you see, I know what it is not to know one’s own body. And so the stories that were fixed in Elizabeth’s perspective unnerved me then. Was she really fat? How fat? And did it even matter? Of course it did. But it doesn’t too. So my unsettlement here is a testament to Awad’s achievement of giving her reader such a feeling of the claustrophobia one can experience living inside a body. Some of it was just all too familiar.

Some of it really was that Elizabeth was also kind of annoying though. Which would be fine, except I think that what I mean by complaining that the character is unlikeable is actually that her lack of evolution is just not very interesting, from a literary point of view. Although it is interesting that so much remains stable for her even as she loses weight—this is quite deliberate on Awad’s part. The novel’s epigraph is from Margaret Atwood, Lady Oracle (I think?): “There was always that shadowy twin, thin when I was fat, fat when I was thin.” At any size, really, the song remains the same.

But it doesn’t have to be that way. And while it is also to Awad’s credit that this is not a heartwarming story about a woman’s struggle overcome adversity and finally accept herself (blech), I wanted something more for the character than what was written. As a kind of stand-in for actual evolution, Awad has Elizabeth changing her name as the book progresses, employing the various possibilities inherent in a name like that. But that literary strategy seemed kind of facile, because I didn’t know Elizabeth well enough to understand what it was she was striving for with her new names, what each one meant.

There is a dawning awareness though. The reader sees this in the story “Caribbean Therapy,” in which Elizabeth goes to a really terrible nail technician, incredulous of the woman’s reality—that here is a fat woman who loves and is loved and is happy. And then in the story “Additionelle,” with its stunning, awful, claustrophobic ending. That she’s trying and trying but not getting any closer to the person she is trying to be, to become. And finally in the last story, “Beyond the Sea,” in which she’s coming to realize the futility of her struggle, that we get one life and why should it be such a struggle, unless you’re Karl Ove Knausgård of course. (I think about this a lot, actually. Not about not being Karl Ove Knausgård, I mean, but that I am 36 years old and I refuse to to spend the next forty years of my life fighting, trying to be less, losing, and then losing again. I refuse to be 70 years old and hating myself because I’m fat. For that matter, I refuse to be 36 years old and hating myself for being fat. And am I fat? How fat? No. I refuse to engage. I’d rather eat a croissant. I’d rather take a walk.)

And then the ending of this story, the final line of the book: “As I watch her [a woman peddling on a stationary exercise machine]… I feel dangerously close to a knowledge that is probably ours for the taking, a knowledge that I know could change everything.” And it was here that I wanted to cheer: Yes, yes, take it, Elizabeth. Because that knowledge is right there. Everything I wanted from this book, for this character, summed up in a line. And it’s a credit to Awad too that all possibilities are wide open right here.

Being happy and fat (and what is fat? how fat? etc. etc.) is not a given, but that knowledge that is ours for the taking seems very much of this moment. Just this morning I read Kaye Toal’s article, “I Promise You Don’t Have to Lose Weight to Be Happy” AND Dr. Yoni Friedoff on how liking the life you’re living is the best way to have a heathy weight, AND just yesterday, Lindy West on how to be a happy fat woman. There are very few ways in which I can say that right now is a glorious time to be living as a woman inside a body, but with such zeitgeist this may be one of them. And it feels good.

I hope that Mona Awad’s character gets the memo too.