November 10, 2017

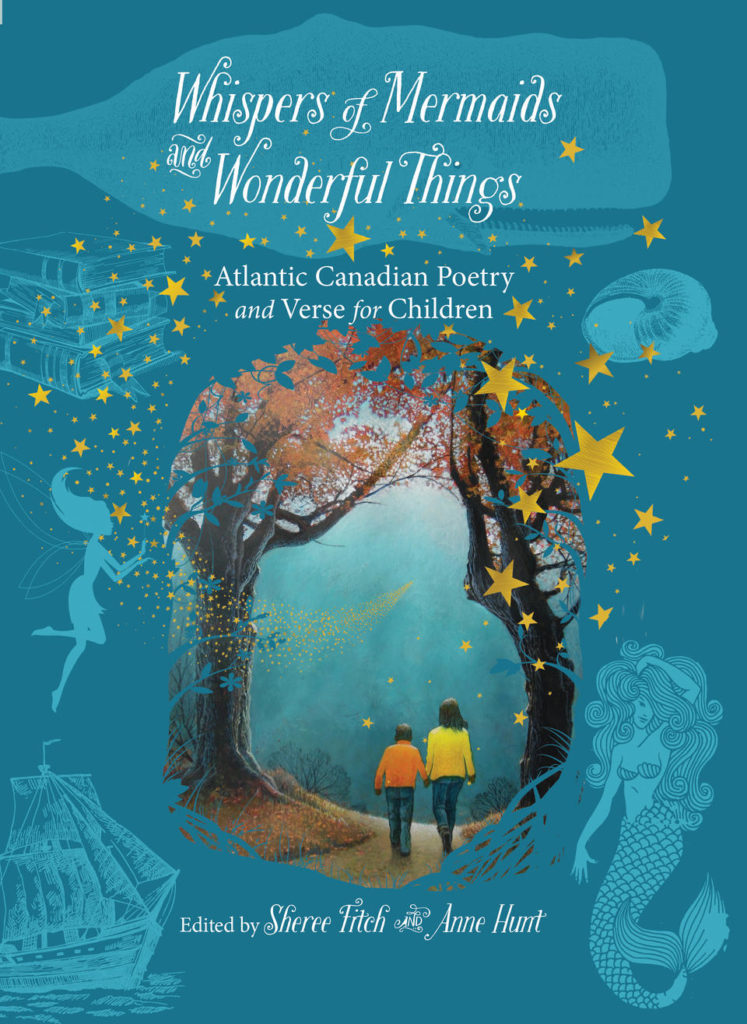

Whispers of Mermaids and Wonderful Things

Full disclosure necessitates I tell you that I had lunch with Sheree Fitch yesterday, although possibly I’m just telling you that because I’m still marvelling at the fact that I had lunch with Sheree Fitch yesterday. Sheree Fitch, whom we travelled to Nova Scotia to see this summer on the day her seasonal bookshop opened. Sheree Fitch is the most extraordinarily generous brilliant person I’ve ever known, a woman whose books have been the framework of my life as a mother and remember when a tiny Harriet crashed the stage to read with her at Eden Mills years and years ago? Although I was one of hundreds upon hundreds of people who traveled to River John, Nova Scotia, to see Sheree Fitch this some, because she is the sort of person who inspires such a gesture.

Even fuller disclosure: Everything Sheree Fitch touches is more than a little bit magic.

Although in the case of her latest project, the anthology Whispers of Mermaids and Wonderful Things: Atlantic Canadian Poetry and Verse for Children, co-edited with Anne Hunt, she’s not the only magic-maker. Credit belongs too to the designer of this gorgeous book whose cover art is absolutely enchanting, along with delightful leafy end pages, borders, and yellow ribbon to hold one’s place. And to her co-editor too, with whom Fitch has selected these works, and to the poets too, some of whom—Fitch herself, Jennifer McGrath, Kate Inglis, Al Pittman—I’m familiar with through their words for children, and others—Lynn Davies, Kathleen Winter, Sir Charles G.D. Roberts, E.J. Pratt, Alden Nowlan—I know if a very different context.

So how do you use a book like this, a pretty book with a ribbon, a book that isn’t a picture book because there aren’t any pictures? Which is to say, how does one awaken the magic within, the whispers of mermaids and wonderful things? And the answer, of course, is to read it. To take book off the shelf and leaf through at random, see where the pages fall open or where the poem catches your eye. To make a ritual of it, a poem before bed, perhaps, or first thing in the morning, like a vitamin. To revel in the words and rhymes, and share that wonder with the people around you. Let beginning readers have a chance to read these poems too, to experience the pleasure saying their phrases, how the words feel in their mouths.

This is a book that will make an extraordinary holiday present for (or from!) anyone with an affinity for words or poems, or an affiliation with Atlantic Canada. It’s such a beautiful object, a treasure, and then you open it up, and there are worlds upon worlds inside to explore.

November 7, 2017

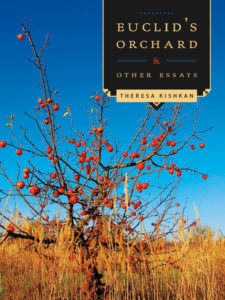

Euclid’s Orchard, by Theresa Kishkan

One of my greatest claims to fame was that I once tied for second place in an essay contest with Susan Olding—whose collection is the wondrous Pathologies: A Life in Essays—and that the first place spot went to the magnificent Theresa Kishkan, who would soon after publish Mnemonic: A Book of Trees. In terms of literature, I don’t know that I’ve ever been in finer company, and I don’t think I properly appreciated this in the moment. Seven years later, I look back and can’t believe that really happened, but I am glad it did—mostly for how it brought me to these authors’ work.

One of my greatest claims to fame was that I once tied for second place in an essay contest with Susan Olding—whose collection is the wondrous Pathologies: A Life in Essays—and that the first place spot went to the magnificent Theresa Kishkan, who would soon after publish Mnemonic: A Book of Trees. In terms of literature, I don’t know that I’ve ever been in finer company, and I don’t think I properly appreciated this in the moment. Seven years later, I look back and can’t believe that really happened, but I am glad it did—mostly for how it brought me to these authors’ work.

In the years since then, Kishkan has published two novellas, and now a new essay collection, Euclid’s Orchard, which I read avidly over a couple of days last week. It’s a book I’d been looking forward to for a long time and whose genesis I knew a lot about and had kind of born witness to as an avid reader of Theresa Kishkan’s blog. Which is also how I knew that these essays, while they explored many of Kishkan’s usual preoccupations, had been written during a particularly trying time in her life, when she was awaiting a scary medical diagnosis, confronting the weight of her history (so much of it left unknown with her parents gone), and contemplating the wonders of her own children coming up in the world, and becoming a grandmother.

The title essay comes at the end of the collection, referring to her son’s proclivity for mathematics, which came as a surprise to both his parents. She writes of trying to understand the codes and languages of her mathematical son’s mind, and of trying to map such understanding onto her own experiences through quilting. But she is also writing about fruit, and grafting, and the orchard she and her husband planted when they arrived at the place that would become their home, and orchard that would be abandoned for reasons the essay delineates. Which is to say that the fruits they would harvest weren’t the fruits that they were planning on—and isn’t it always the way? There’s not a formula for that. Nor for keeping out the coyotes and the bears either. Kishkan is writing about patterns, and functionality, and parenthood, pollination, and Fibonacci numbers, and coyotes singing:

They were our names, our bodies under the heavens, all of us singing together in different voices to tell the story of our orchard, our time here, in this place we have inhabited since—for John and me—1981, and the only way to shape the story is through connotation, not ordinary discourse, though I praise the literal, the specific, but by reaching up into the starlight to parse what lies beyond it.

Reaching up into starlight (figuratively speaking) is also the only way left to search for answers to the gaps in Kishkan’s parents’ histories, particularly as historical documentation has proven elusive and misleading. In two essays, she tries to make sense of these gaps and the documents, as she searches for her mother’s birth parents—her mother had been born to an unwed mother and raised as a foster child—and as she explores the history of her father’s family, immigrants from what is now the Czech Republic who become homesteaders near Drumheller, AB, although some sleuthing reveals her grandparents had been squatters whose petitions to own the lands they lived on had never been successful. And what do they mean, all these pieces and gaps in her history. As Kishkan writes, “the only way to shape the story is through connotation,” and Kishkan does this masterfully.

In the other pieces, she writes directly to her remote father who always seems disappointed in his sons, who had never properly regarded his daughter. On what to do with a fifty-year-old bottle of her mother’s perfume. She writes about the landscapes of her childhood, places firmly etched on the map of her mind. About trees and flowers, cuttings the history and stories of gardens—and this book is a nice complementary read to Helen Humphreys’s new book, The Ghost Orchard, which I read not long before it. Euclid’s Orchard is a collection of fascinations and astonishments, of the world as it is and was and is ever becoming.

November 6, 2017

The Intricate Properties of Teacups

“How well we artists and writers know the chances of our work sinking into the abyss! And yet how grateful we are to be able to make these marks, to live a life that risks blooming in the bracing cold, that can offer tender furled messages, indecipherable traces. A life that has allowed us to sink into the knowledge of the real and difficult abundance, while merely sitting before a white teacup on a table. It is something, as well, to pay attention to traces of these fine eruptions of gratitude that escape into paint. For we have much yet to learn about how souls connect, let alone about the intricate properties of teacups, their simple gleaming.”

—Calm Things: Essays, by Shawna Lemay, “Of Coffee Pots, Teacups, Asparagus and the Like”

November 5, 2017

Cozy Inside

It’s so dark, but I’m not tired of it yet. It’s still novel, and my house is warm with all the lights on. I’ve literally got an illuminated banner hanging up in this room right now whose letters read LIGHT LIGHT so I guess you can see that we’re really trying here. And it’s working. I really do love evenings like this, the world so dark outside our windows but everything bright and cozy inside, each of us here exactly where we belong.

It hasn’t been the easiest season, for reasons that are mostly (and blessedly) unremarkable, the usual business of life. It’s not been terrible either, but it’s also been busy, and while we’ve had many adventures and good fun with excellent friends, this Saturday was the first Saturday in at least a month or maybe more where we had absolutely nowhere to go. And it was perfect, the way an empty Saturday can be, the way it isn’t when everyone is tired and the house is too small and nothing good is in the cupboard. No, everything was completely the opposite of that, and yesterday was cold and bright and sunny. We didn’t leave the house until after two o’clock, when we headed to the library, and we’d had bread and jam for breakfast, and played games, and then Harriet made a video game about putting all your apples in one basket (and it turned out fine!). At the library, amazing books we out on display, and we got the new Carson Ellis and whole stack of Bob Graham books, the brand new Girls Who Code book by Reshma Saujani, and a book of kitchen experiments about growing mould that for some delightful but obscure reason was exactly what Harriet was desiring.

We walked home via Kensington Market, and bought bagels. And then arrived home to the smell of bread in our bread-maker, nearly done. And I made that one kind of soup that my children will consent to eat, which is pretty much devoid of flavour, but it’s still soup and they eat it which means we’ve come a long long way. All I’ve ever wanted really are children who eat soup, so I won’t quibble, and their company at dinner was delightful. It’s been that way most of the weekend actually, which is so so nice. When we turn to each other and say, “Don’t you just adore these funny people we made?”

(This is in contrast to early in the week when one of those funny people kept coughing in bed and we were contemplating making her sleep in the shed.)

Today was the day with twenty-five hours in it, which is always my favourite day of the year, and this year it once again delivered, never mind that I probably spent my extra hour in bed struggling to go back to sleep after creepy dreams were keeping me up in the night—I’ve been reading too many intense novels lately. We had cottage cheese pancakes this morning and hung out reading newspapers and the children entertained themselves, and we made banana bread. After lunch, we went to the pool and spent a delightful hour frolicking in the shallows, which saved us from a day of doing absolutely nothing at all and going stir-crazy. We came home and I read books while the kids watched TV, and then Stuart made dinner, and Harriet and Iris and I made guacamole, except Iris kept calling it Whack-a-moley. And Iris even ate it! (“And Iris even ate it!” is the unbelievable incredible ending to so many stories I tell.)

Today was the kind of grey and rainy Sunday you just hope will come along, during those rare and precious times when you’ve got nothing else to do. This entire weekend feels as restorative as a week-long vacation, and we don’t even have to unpack.

November 3, 2017

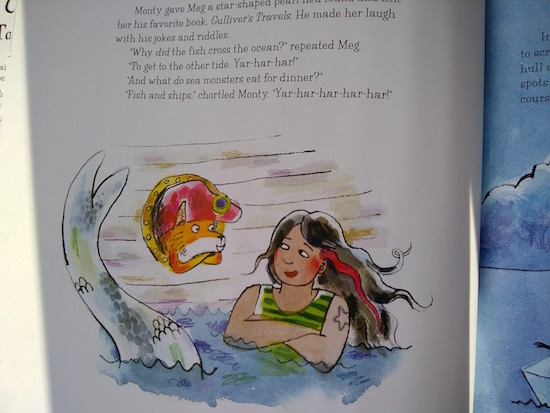

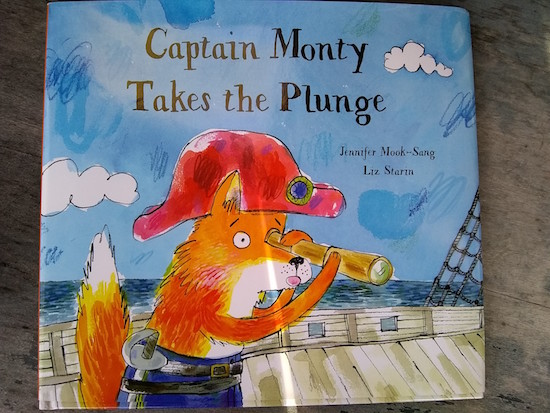

Captain Monty Takes the Plunge, by Jennifer Mook-Sang and Liz Starin

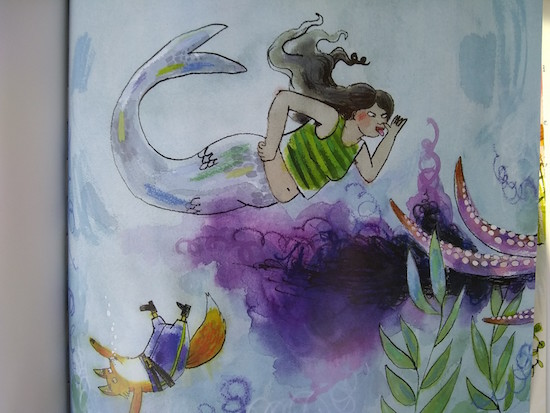

Is it wrong to fancy a mermaid? Well, it mustn’t be so wrong, because sailors have been doing so for centuries. But is it wrong to fancy a mermaid in a picture book? One who’s already in a relationship with a pirate who is also a cat? Well, if loving a picture book mermaid is wrong, I don’t want to be right.

And it’s not like Meg is just any picture book mermaid. “She’s like you, Mommy,” said my daughter. “She has a star tattoo.” And I remind my daughter, “We also both have awesome squishy tummies.” Because Meg the mermaid is the kind of mythical creature you want to have a lot in common with. She’s cool. She plays the ocarina, likes bad jokes, and she teaches Captain Monty how to set his course by the constellations, which is a useful thing for a pirate captain to know.

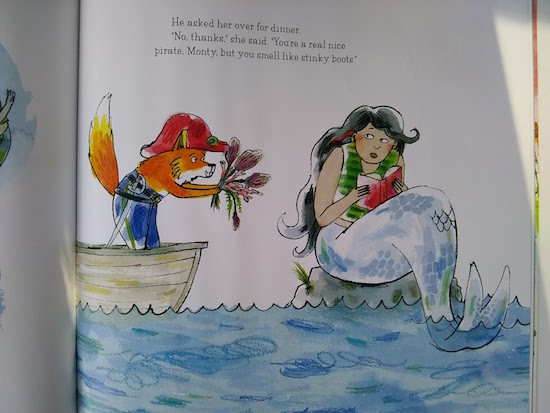

While she might be a punk rock mermaid, Meg still swims like a fish, displaying amazing skills that put poor Monty (who’s afraid of water) to shame. And she’s got standards too: when Monty asks her out, Meg turns him down. Because a guy who’s afraid of water never gets a chance to bathe, and she tells him, “You’re a real nice pirate, Monty, but you smell like stinky boots.”

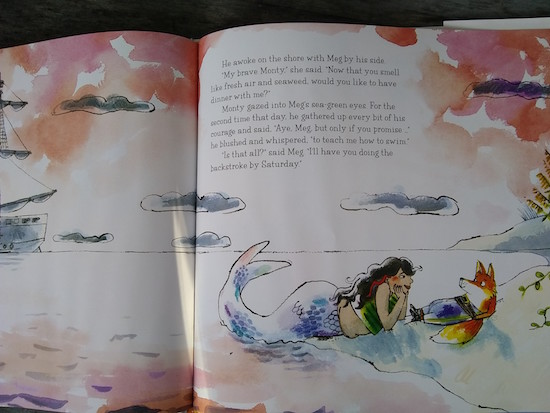

When Meg gets captured by an octopus, however, Monty has to step up to save her. Which he kind of fails at, until he thinks up a clever way to outwit the many-legged sea creature, and Meg joins in on the action, the two of them rescuing themselves together. And all that is pretty romantic, so of course they fall in love. “My brave Monty,” Meg tells him. “Now that you smell like fresh air and seaweed, would you like to have dinner with me?”

Captain Monty Takes the Plunge, by Jennifer Mook-Sang and Liz Starin, is a fun and lively book for any young reader who’s into pirates, dislikes bathing, and/or requires just a few more ounces of courage before she leaps into the pool. But it’s Meg who steals the show, a fabulously subversive and feminist rad mermaid, and she’s the reason we keep returning to the book again and again.

November 2, 2017

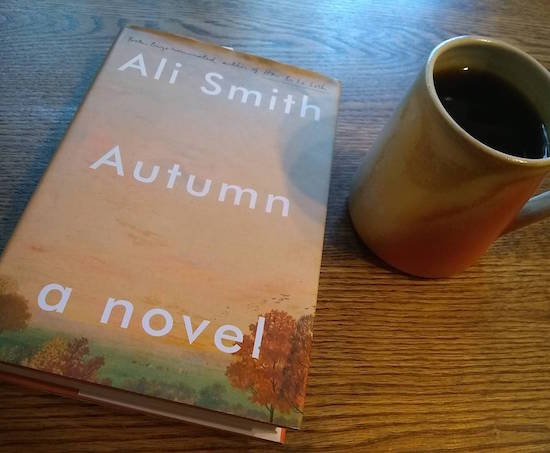

Rereading Autumn in autumn.

I returned to Ali Smith’s Autumn because when I read it in April I was as baffled by it as I was entranced. And I returned to it also because it was actually autumn, October: “October’s a blink of an eye. The apples weighing down the tree a minute ago are gone and the tree’s leaves are yellow and thinning. A frost has snapped millions of trees all over the country into brightness. The ones that aren’t evergreen are a combination of beautiful and tawdry, red orange gold the leaves, then brown, then down./ The days are unexpected mild. It doesn’t feel that far from summer, not really, if it weren’t for the underbite of the day, the lacy creep of the dark and the damp at its edges, the plants calm in the folding themselves away, the beads of condensation on the web strings hung between things./ On the warm days it feels wrong, so many leaves falling./ But the nights are cool to cold.” And now it is November, which is the very point.

I finished rereading Autumn and was no less baffled than I was the first time, which normally would frustrate me, but there are so many things in this novel that function as footholds, even when reading makes me totally lost. The characters of Elisabeth and Daniel, the satire of post office bureaucracy, the beautiful writing, the contemporary nature of the setting, its immediacy. (“It is like democracy is a bottle someone can threaten to smash and do a bit of damage with.”) I got such comfort from that when I read this in the spring, the world being too much with us—and yet somehow it was helpful, a comfort, to find it in a book. Upon rereading I underlined the part (though I underlined many parts) when Elisabeth is reading A Tale of Two Cities and sees her own reality reflected in literature: …it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness… And Smith writes, “The words had acted like a charm. They released it all in seconds. They’d made everything happening stand just far enough away.” [Emphasis mine.]

The main character in the novel (apart from the man who is a tree, obviously…) is a lecturer in art history, and art features prominently in the story, particularly the art of Pauline Boty, who was a founder of the British pop-art movement and its only female painter. Both worked in collage and I got the sense that Smith’s novel is kind of a literary homage to her style, figures and ideas from current events cut out of newspapers and magazine and glued onto a surrealist background. The kind of art I’d take my kids to see exhibited, even though we don’t fully understand the project, because so much in the images are recognizable, remarkable, and interesting in their new contexts.

This time when I read I took note of all the instances of “leaf,” and “leaves,” and trees and scrolls. On the remarkable ways that book speak to the world around us (like when Elisabeth is reading Brave New World in the post office and comes across an allusion to Shakespeare, looking up at the very moment to see an advertisement for a Shakespeare commemorative coin on display), what the novel says about neighbours and neighbourliness in the age of Brexit, about what is story and what is fiction and what is real, about drawing lines and blurring lines, divisions and connections. And speaking of lines, my very favourite one in the entire book continues to be, “Whoever makes up the story makes up the world,” which is an idea that continues to fascinate me. When Elisabeth is asked a question, “Why should we imagine that gender matters here?”

Also, “Time travel is real… We do it all the time. Moment to moment, minute to minute.”

And so, here we are.

October 31, 2017

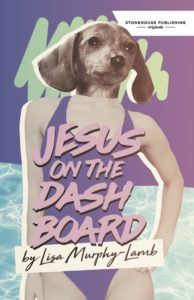

Jesus on the Dashboard, by Lisa Murphy-Lamb

When I was in Edmonton in September and Stonehouse Publishing won the Emerging Publisher of the Year Award at the Alberta Book Publishing Awards, I had some familiarity with the press—mostly because the day before the bookseller at Audreys had taken care to bring me all their books as examples of a small press making beautiful books and doing it well. The only reason I didn’t end up buying one of their books was because they were historical fiction, which isn’t always a genre I go for, but when I learned that one of their latest releases is set in the 1980s, which is one of my favourite periods in all of historia, I was immediately keen. Even more so when I saw the cover, and read the synopsis; Lisa Murphy-Lamb’s Jesus on the Dashboard, I decided, was right up my street.

When I was in Edmonton in September and Stonehouse Publishing won the Emerging Publisher of the Year Award at the Alberta Book Publishing Awards, I had some familiarity with the press—mostly because the day before the bookseller at Audreys had taken care to bring me all their books as examples of a small press making beautiful books and doing it well. The only reason I didn’t end up buying one of their books was because they were historical fiction, which isn’t always a genre I go for, but when I learned that one of their latest releases is set in the 1980s, which is one of my favourite periods in all of historia, I was immediately keen. Even more so when I saw the cover, and read the synopsis; Lisa Murphy-Lamb’s Jesus on the Dashboard, I decided, was right up my street.

The novel is about Gemma, seventeen-years-old, whose mother’s departure years before has been somewhat traumatizing, part of the reason why Gemma is remote from her peers and her father, refuses to be touched, has food issues, and why her deepest bond is with her therapist. Which makes it all the more surprising when Gemma’s estranged mother’s cousin Rachel (who one shared a house with Gemma’s parents) turns up with her eldest daughter with a curious invitation for Gemma—and Gemma even accepts it. It seems that Rachel has changed her wild ways and become a born-again Christian, as has Rachel’s mother Angie, and they both attend the same church in Springbank, Alberta. And now Angie has gone and adopted a Korean orphan in an effort to find her way back to motherhood, and Rachel wants Gemma to be part of that journey—would Gemma like to come and spend the summer with her family?

Of course she goes, because the premise of seeing her mother again is irresistible, but it’s not that straightforward, because Angie knows nothing about Rachel’s plan, but Rachel has been praying, and Rachel has faith. And in the meantime, Gemma finds herself part of a busy raucous household nothing like the one she shares with her father, and she has to navigate the complicated social terrain of her cousin Penelope who tells her, “I may be churchy, but I’m no virgin.” Consistency is overrated, which is probably a good lesson for anybody to learn early, and I loved Murphy-Lamb’s depiction of Penelope and her friends who embrace their faith and the world and all that contradiction…which is what saves Gemma in the end when the show-down with her mother finally happens, and she realizes she’s stronger than she ever knew.

Murphy-Lamb writes great prose with humour, and crafts her characters with a loving sympathy that will totally win your heart. “I’m glad I went,” Gemma tells her therapist at the end of it all. “If I hadn’t gone, I would have spent the summer surrounded by double garages, aerated lawns, stuccoed houses, and my own self-loathing.” A line that tells you something about the singularity of her narrative voice, the way that Murphy-Lamb strikes the right balances between precocious and naive, impossibly young and wise-beyond-her-years, and something too about the joy of having access to her stream of consciousness. At some points I found the narrative hard to follow and the book could have benefited from a tighter edit, but neither of these points overrode my appreciation for the novel, whose ending is just fantastic.

October 27, 2017

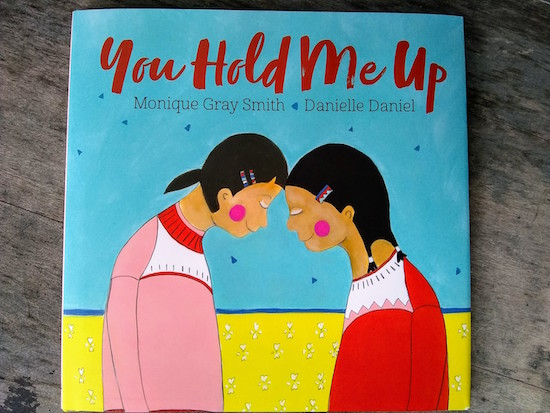

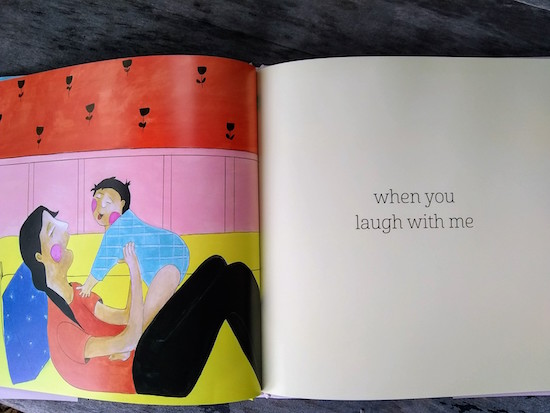

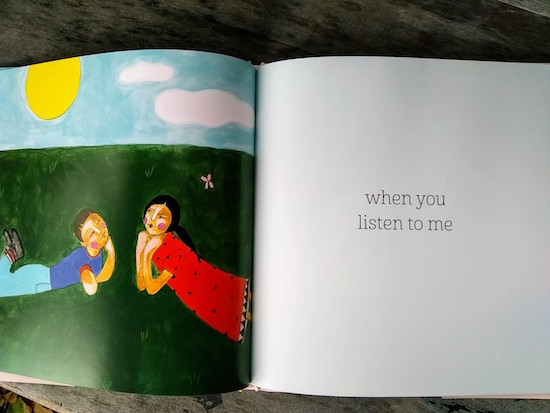

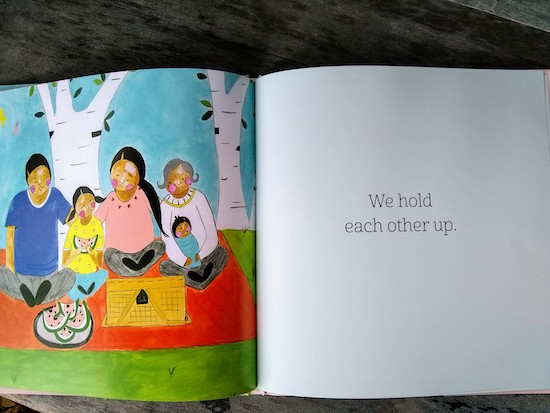

You Hold Me Up, by Monique Gray Smith and Danielle Daniel

My children delighted in You Hold Me Up, by Monique Gray Smith and Danielle Daniel. As we read it, my littlest kept guessing what the text might be based on the image. “When you dance with me!” she offered, for the “you hold me up when you play with me” page, so she wasn’t wrong. She also guessed, “When you yawn with me,” for “when you sing with me,” which is a little bit wrong, but then we all started yawning, underlining the point of the book, that we’re all connected to each other.

Monique Gray Smith is the award-winning author of Tilly: A Story of Hope and Resilience, and children’s books My Heart Fills With Happiness (which I read last year) and Speaking Our Truth. I also really recommend her podcast, Love is Medicine. Illustrator Danielle Daniel won the Marilyn Baillie Picture Book Award for her first book, Sometimes I Feel Like a Fox, which we loved, has another new picture book just out, Once in a Blue Moon, and I also really liked her memoir for the adult set, The Dependent—my review is here. The idea of these two teaming up on a project has had me looking forward to You Hold Me Up for ages.

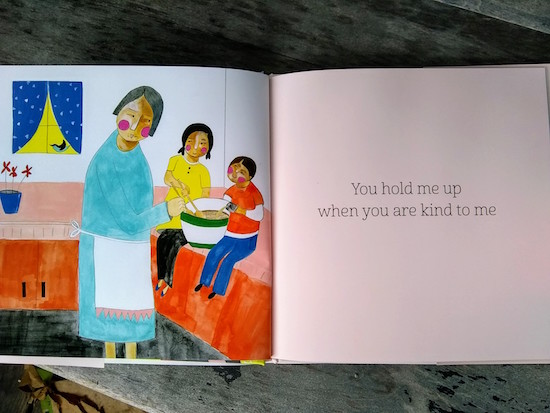

Smith’s text is simple, but powerful, about the small and essential ways we all support each other. “You hold me up when you are kind to me…” it begins, accompanied by a photo of an Indigenous family in the kitchen baking together. “…when you share with me…when you learn with me.” Daniel’s illustrations have a playful approach, but are also nicely stylized and textured, with a collage effect and fine details, warm and familiar images of people together.

“It’s about family,” Iris proclaimed when we got to the end of the story, the line, “We hold each other up,” with the facing image of two adults, their children, and a grandmother having a picnic under birch trees. And she’s not wrong here either, except it’s not only that. Smith writes in her Author’s Note of Canada’s “long history of legislation and policies that have affected the wellness of Indigenous children, families and communities.” Like her My Heart Fills With Happiness (and in everything she does, really) Smith is writing about survival and resilience, about the strength and power that comes from the love we give each other.

October 26, 2017

Dozens of Umbrellas

“In the meantime, I found work in a dollhouse shop. We sold tiny things to put in them, from lamps to Robert Louis Stevenson books with real microscopic words in them. Peter got a job in a graveyard, installing tombstones, digging graves, helping with Catholic burial processes, and cleaning up messes. He would find diaphragms, empty bottles of spirits, squirrel kinds left over from hawks’ meals, and dozens of umbrellas. He brought the umbrellas home, until our apartment started to look like a cave of sleeping bats. I had an umbrella sale one Saturday when he was at work:

ALL UMBRELLAS TWO DOLLARS AS IS

It was an overcast day so I did well for myself. ”

—From “The Mouse Queen,” by Camilla Grudova, in The Doll’s Alphabet

October 25, 2017

F-Bomb: Dispatches From the War on Feminism, by Lauren McKeon

There were women who actively campaigned against universal suffrage. When I learned about this a while ago, the revelation stunned me—but also was something of a comfort. That this kind of lunacy was not without precedent, I mean. That women (and people in general) have always been self-defeating and so obstinate. It’s almost admirable. Almost. But not really, because it’s also dangerous and stupid and it terrifies me. Last fall I spent an inordinate amount of time arguing with strangers on twitter about feminism, in one circumstance about why MPs shouldn’t have to put up with being called “ugly cunt” and threatened with rape or death, for example. Suggesting that this was a gender problem, mostly because this sort of thing didn’t happen to MPs who weren’t women, but plenty of women disagreed with me. Online abuse, they informed me, is simply part of life, and to suggest that women weren’t tough enough to take it, to roll with the punches, was a blatant example of sexism. And it was roundabout this point that my brain twisted into a pretzel shape, and then my head completely exploded.

There were women who actively campaigned against universal suffrage. When I learned about this a while ago, the revelation stunned me—but also was something of a comfort. That this kind of lunacy was not without precedent, I mean. That women (and people in general) have always been self-defeating and so obstinate. It’s almost admirable. Almost. But not really, because it’s also dangerous and stupid and it terrifies me. Last fall I spent an inordinate amount of time arguing with strangers on twitter about feminism, in one circumstance about why MPs shouldn’t have to put up with being called “ugly cunt” and threatened with rape or death, for example. Suggesting that this was a gender problem, mostly because this sort of thing didn’t happen to MPs who weren’t women, but plenty of women disagreed with me. Online abuse, they informed me, is simply part of life, and to suggest that women weren’t tough enough to take it, to roll with the punches, was a blatant example of sexism. And it was roundabout this point that my brain twisted into a pretzel shape, and then my head completely exploded.

And so while the general content of Lauren McKeon’s new book, F-Bomb: Dispatches from the War of Feminism, would not come as news to me, the book itself actually proved to be a comfort. Showing me that I hadn’t gone completely insane, for example, as my conversations on Twitter were really causing me to think I had, and that anti-feminism is indeed an actual phenomenon. Which, when unarticulated, seems encroaching and awful, when suddenly everyone who’s wrong gets to be right (and very loud). But McKeon situates the phenomenon in its own context and the context of our current political nonsensicalness, and her analysis actual made me feel better. As in, here is a thing and it’s insane but it’s also graspable, and the only thing any thinking person can do is try to understand it and to learn.

“[E]early feminists…largely protested abortion, at least in public. Still, as much as we owe a debt to these women, I’m not about to grab a petticoat and try to be them. I might picture myself standing on their shoulders, but its not in a straight and unwavering line. Rather, it’s an inverted pyramid that allows for pluralities and expansion, a rejection of this idea that it’s good to go backward.”

“An inverted pyramid that allows for pluralities and expansion” is a fair articulation of McKeon’s feminism in general, and I love that. I appreciate too the way that she necessarily complicates the idea of first/second/third/fourth wave feminisms too: “As much as older feminists can seem surprised and baffled by younger feminists, the lines aren’t strictly generational; they’re ideological.” Calling upon a discussion of generational divides by Bitch co-founder Lisa Jervis, McKeon writes: “Categorizing feminism into waves flattens the differences in feminist ideologies within the same generation and discounts the similarities between different ones, all in one fell swoop… When we buy into the wave theory, we forget common goals, like the fight for abortion rights, equal pay, and ending violence against women.”

But while McKeon suggests that feminism can indeed thrive on difference, she affirms that we’re nowhere near there yet. White women, she writes, still have ways to go in confronting their privilege, in complicating their own understandings of feminism, and moving over (or even sitting down) to make room for other voices. “If feminism wants to survive and grow, not shrink, it’s vital that it learn how to communicate within itself.”

Because here’s what feminism is up against, as McKeon delineates in the rest of the book: there is the usual chorus of “I’m not a feminist, but…” people, who are only too happy to benefit from the movement, while contributing nothing to it. Men’s rights organizations are on the rise, and women are jumping on board their bandwagon. McKeon delves into the Men’s Rights movements, while never losing her feminist footing (“The men’s rights movement is fond of saying its members don’t hate women. What a load of BS… That’s akin to saying an abusive husband likes his wife. Whatever, buddy; that’s not the point.”) McKeon finds roots of the movement in 19th century magazine editorials, and in the 1989 Montreal Massacre too, whose perpetrator hated feminists. What’s new, however, is the movement’s modern rebranding toward a superficial notion of equality, claiming a universality due to the women who are happy to be its public face.

McKeon speaks to some of these women, who are unabashed in their contradictions (and, usually, in also their ignorance too). A Thunder Bay housewife who writes about how women shouldn’t have the right to vote (who concedes that her brash online persona is mostly bluster and clickbait—and this is a problem, the damage done by so-called provocateurs who are literally profiting on online outrage). A writer of erotica whose website was trolled by anti-feminists…who led her to their website, and won her over, and now pulls in thousands of dollars per speaking engagement. These women’s con-jobs, McKeon writes, are remarkable: “convincing women to shun victimhood without actually doing anything to make us not victims… They’re like the Houdinis of discrimination and hate, conjuring up amazing illusions. Underneath it all, though, the message is essentially: let’s keep things unequal for women, so everybody wins!”

She goes on to critique opt-out culture and the domestication of pre-feminist gender roles, which feeds right into men’s rights rhetoric and fuels the faux-polarization of stay at home moms and working ones, which obscures realities including class. These nostalgics also forget that 1950s housewives were miserable, purged from postwar jobs and stuck in the suburbs on tranquilizers, and blamed for everything that was wrong with their children. It was not a great time, folks. And those who think it was have misunderstood the intentions of second-wave feminists—McKeon points out that Betty Friedan “wanted better treatment for housewives, not to abolish the role.” The myth of “having it all” was invented not by feminists, but by journalists, who’ve been trying to sell magazines (and pitting women against each other) with it for decades.

It is the context of a conscious effort to keep women out of the workforce that McKeon writes about “Gamergate,” the online movement targeted at abusing women who wanted to have a voice in the video game industry—and precedent for the dumpster fire that was the 2016 US Presidential Election. But it also stands for the way that women are driven out of lots of industries, McKeon posits, often for being pregnant, or having sick children to care for. Or simply because they can’t afford the costs of childcare. And anti-feminists dispute all of this, of course. The wage gap is a lie, they’ll tell you. McKeon writes, “By capitalizing on women’s anxieties about doing/having/being it all, and simultaneously crafting these neat little pretzel knots of logic, anti-feminists have helped strengthen the silence.”

And speaking of silence, she writes about women denying rape culture and the violence of sexual assault—including the groups of mothers whose sons have been accused of rape and have started a group in support of boys in their sons’ situations, actively trying to convince women that the things that happened to them weren’t even rape after all. (“‘You can make a good faith mistake about whether you were raped,'” Stotland assured me, presumably benevolent, like a fairy godmother of victim blaming.”)

She writes about the rebranding of anti-abortion activists as pro-women as well, and the ways in which their movement is gaining ground, with access to abortion becoming more and more difficult across the United States (and in some parts of Canada, it’s never been great anyway). Is “pro-life feminism” even a thing? McKeon quotes an activist, “The future is pro-life female… We’re not trying to control women or take over their bodies—that’s not it at all… We believe you should have control over your body from the moment it first exists.” McKeon writes that pro-life feminism lacks an agenda beyond being anti-abortion, and that its rhetoric is unlikely to take hold in the feminist movement proper… “But can I see it working alongside the anti-feminist and post-feminist movements to crush modern intersectional feminisms and the reproductive and sexual rights around which they mobilize? Well, yeah, sure, I can see that.”

The book ends on a hopeful note, you will be happy to know. McKeon’s second-last chapter is about young empowered feminists who waging brave and awesome campaigns, both online and in the world. She goes back to high school, where her own feminism was born in a gender studies class, and is inspired and moved by the conversations she sees happening there. The idea that young women don’t care about feminism is a myth up there with “having it all.”

And then she concludes her book with her trip to the Women’s March in Washington on January 21 2017, a monumental event whose media coverage fuelled discord and served the anti-feminist agenda exactly…except the Women’s March was a triumph. The Women’s March was amazing.

“Was the Women’s March on Washington a crucial time for women to join together, or was it an opportunity to confront its historically privileged and narrowly rigid roots?” McKeon asks. The answer is simple. The answer is easy (but it also isn’t). The answer is affirmatively positive: McKeon answers, “Yes. And yes.” And the rest of her book is the reason why she and her reader are so emphatic that this must be the case.