November 30, 2017

Eating all the pies

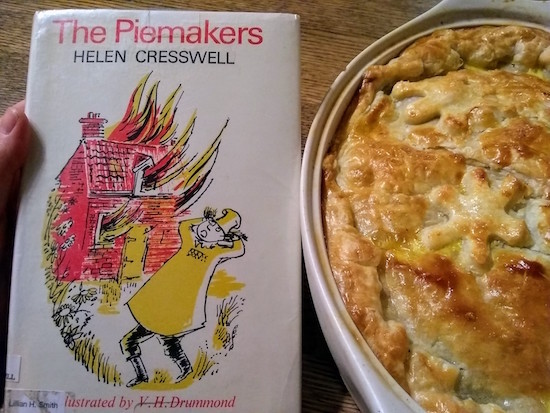

I felt very liberated when I read in a cookbook about pies that one should use store-bought puff-pastry always, because attempting to make puff-pastry from scratch was just stupid. I don’t really know if the author of my pie book is an authority (according to wikipedia, she’s an interior designer and pies are just a sideline) but I’m not going to ask too many questions, because puff-pastry makes pies so easy. Savoury pies, I mean, as in for a meal. I still have pretty strong feelings about pastry from scratch for fruit or dessert pies. But puff-pastry means you could have a meat pie on the table as an easy weeknight supper. And we were all over that while we were reading The Piemakers, by Helen Cresswell, which our librarian recommended to us recently and we read-aloud with pure delight. A story that reminded me so much of The Borrowers in tone that I kept forgetting that the characters were not miniature—although the giant pie dish in which they float down the river didn’t make the scale any less confusing. It’s about a family of pie-makers—the daughter is called Gravella, named for Gravy—and it all goes wrong when they get the opportunity to bake a pie for the actual king. (Too much pepper, cough cough.) But then they get another chance to redeem their pie-making reputation, and everyone in the village pitches in, and (spoilers!) the result is a pie-making triumph. We loved it. But it made us hungry. And let me tell you the other best thing about store-bought puff pastry? That it’s sold in packages of two.

November 30, 2017

The Marrow Thieves, by Cherie Dimaline

Do you know what’s NOT very original? Me writing about The Marrow Thieves, by Cherie Dimaline, that’s what. The book that won the OLA White Pine Award, the Governor General’s Award for Young Readers, the big-deal Kirkus Prize, among its many accolades, and has since run out of space on its cover for awards. I first encountered Dimaline at The Festival of Literary Diversity in 2016 on a fantastic panel about faith in literature, and she was so impressive I bought her short story collection A Gentle Habit right after and I really liked it. But even so, I was less inclined to pick up her novel that followed it, because I was all, “YA dystopia, huh? No way.” Partly because of my own genre-biases, it’s true, but also because the world is dark enough: why should we throw a pack of post-apocalyptic teens into the mix?

Do you know what’s NOT very original? Me writing about The Marrow Thieves, by Cherie Dimaline, that’s what. The book that won the OLA White Pine Award, the Governor General’s Award for Young Readers, the big-deal Kirkus Prize, among its many accolades, and has since run out of space on its cover for awards. I first encountered Dimaline at The Festival of Literary Diversity in 2016 on a fantastic panel about faith in literature, and she was so impressive I bought her short story collection A Gentle Habit right after and I really liked it. But even so, I was less inclined to pick up her novel that followed it, because I was all, “YA dystopia, huh? No way.” Partly because of my own genre-biases, it’s true, but also because the world is dark enough: why should we throw a pack of post-apocalyptic teens into the mix?

But we should, actually, as advised by Shelagh Rogers who tweeted, “I am delighted @cherie_dimaline. The Marrow Thieves is billed as YA. I urge A’s to read it!!” And then this fall everywhere I went, people kept asking me, “Have you read it yet?” Until finally, I had no choice but to buy it, and I am so glad I did, because (and you never saw this coming): The Marrow Thieves was amazing!

Although it took me a few pages to settle into it, to get a sense of the shape of the narrative. It’s from the point of view of Frenchie, a 17-year-old who travels through the wilderness of Northern Ontario with a ragtag family of kids and a couple of elders ever on the move to escape the clutches of “the recruiters,” officials who take Indigenous people away to special “schools” where their bone marrows are harvested. The reason? Climate change has sent the environment into turmoil and as a result of the devastation people have lost the ability to dream—except for Indigenous people, whose resilience and connection to the land has enabled them to survive one apocalypse already and whose dream lives are an essential part of their cultures. And so the bone marrow of Indigenous people become coveted, the key to recovering the ability to dream without which people the world over are going mad.

The book begins with Frenchie’s brother being taken by the recruiters, after the boys have already been separated by their parents and the world is a dangerous, toxic place. Using his wiles, as well as his connection to the land and remarkable abilities in hiding and climbing, Frenchie gets away from the recruiters and is eventually found by Miig, who tells Frenchie and the other children who travel with him the story of what has happened to their land and their people, some of this story still speculative to novel’s the reader and much of it historical fact. We follow Miig and Frenchie and the rest of their found-family, learning the often harrowing stories of how many of them came to join the group.

But soon the recruiters are getting closer, and the stakes are getting higher. Three quarters of the way through, this novel becomes so difficult to put down and part of the appeal is that all its darkness is underlined with such abundant joy. The love story between Frenchie and Rose is part of this, as well as the family love between Frenchie and Miig and the other members of their group, and the strength and wisdom they carry on their journey that seem incorruptible. Amidst the YA darkness is the rich spirituality of the novel and its sense that some things—love, not least among them—are inconvertible. That life and love and land are worth surviving for.

And the third last page! The third last page! It had me audibly gasping like a, well, like a grown up devouring a YA dystopian novel in all its incredible goodness. I still can’t get over that third last page, and what it leads to. I loved this book, and urge you to pick it up if you haven’t read it yet.

November 27, 2017

Your Heart is the Size of a Fist, by Martina Scholtens

After a few days stuck in a reading rut, I knew I was probably going to enjoy Your Heart is the Size of a Fist, by Martina Scholtens MD. I’d flipped through it and supposed this was a collection of vignettes about a doctor’s experience working with patients at a Vancouver refugee clinic, a timely topic with the arrival of thousands of Syrian refugees in Canada over the last two years, and considering that our previous Federal government had seen fit to cut refugee healthcare—a decision that was reversed when the Liberal government restored benefits in 2016. A few passages jumped out at me—there was a bit about Canadian sponsors and infantilization of the refugee families they’d supported, which is something I’ve been thinking about a lot, the complexity of those relationships. This would be a book I’d find interesting, I knew.

After a few days stuck in a reading rut, I knew I was probably going to enjoy Your Heart is the Size of a Fist, by Martina Scholtens MD. I’d flipped through it and supposed this was a collection of vignettes about a doctor’s experience working with patients at a Vancouver refugee clinic, a timely topic with the arrival of thousands of Syrian refugees in Canada over the last two years, and considering that our previous Federal government had seen fit to cut refugee healthcare—a decision that was reversed when the Liberal government restored benefits in 2016. A few passages jumped out at me—there was a bit about Canadian sponsors and infantilization of the refugee families they’d supported, which is something I’ve been thinking about a lot, the complexity of those relationships. This would be a book I’d find interesting, I knew.

What I was not anticipating was that I’d be so compelled by the work as literature, for its shape as a memoir, the glimmer of its prose, and for its depth and richness as memoir. These are not just stories of Scholtens’ patients, the story of her work, its challenges and contradiction, its joys and satisfactions. The book is framed by Scholtens’ engagement with a family newly arrived from Iraq (although, as she writes in her preface, her patients in the book are composites of actual people for privacy concerns) and also by her own family life as she suffers a miscarriage and then later becomes pregnant again, giving birth to her fourth child. She counsels the Haddad family through their health concerns (PTSD among them), works to diagnose their son’s developmental problems, talks to their teenage daughter about sexual health, and gives the girl’s mother advice about how to get pregnant all the while being wary of the many health risks involved. Along with this family, we are shown glimpses into Scholtens’ relationships with other patients, from Kenya, Myanmar, Syria and Iraq.

It is with Scholtens’ own pregnancy loss and the profound way in which her own healthcare provider is present for her that she has a revelation about the role she plays in her patients’ lives. Previously, she’d felt uncomfortable with their profound gratitude toward her when she felt as though she wasn’t really providing anything, or certainly only providing to piecemeal solutions to the problems they were working to overcome in their lives. But she comes to understand the value of a physician just to bear witness and listen. She comes to understand too that while the gifts her patients bring for her, for example, might make her uncomfortable, her patients are seeking to balance a relationship in which they feel profoundly indebted. Or else gift-giving is an important cultural touchstone for that particular patient—and there funny and lovely anecdotes depicting these interactions.

Bearing witness is no small thing though, and Scholtens writes beautifully about her own struggles. What does it do to one’s spirituality and notions of God and good and evil, to see evidence of the harm and trauma that people can inflict on others? How does she reconcile her own comfortable life in contrast to the poverty and social isolation of the people she cares for? How to balance the demands of her job with her own mental health and general wellbeing—not to mention the demands of caring for four children? How to bridge cultural gaps without undermining the essential nature of cultural identity and religion?

Your Heart is the Size of Your Fist becomes a story of how a doctor learns from her patients the answers to all these questions, or at least discerns clues as to the direction to go in search of answers. To say that it’s an uplifting and breezy read should not undermine the spiritual weight of Scholtens’ story and its importance—but hopefully it will compel you to read it.

November 24, 2017

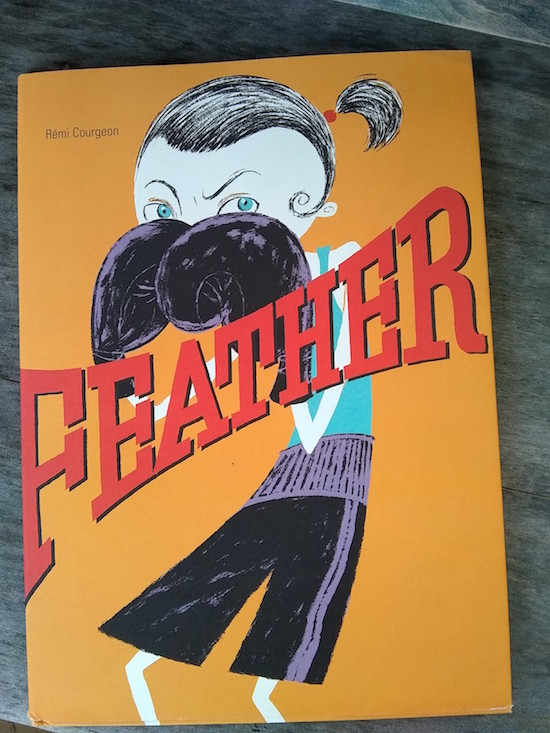

Feather, by Remy Courgeon

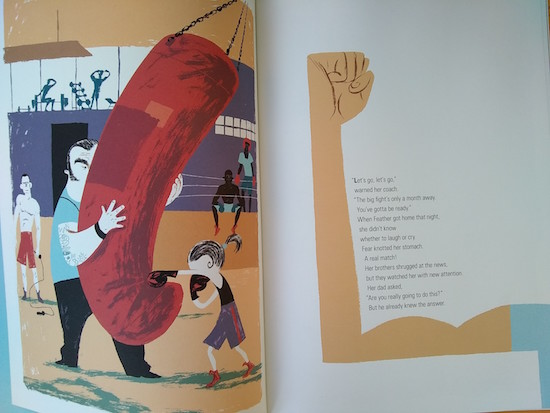

So I’m not exactly blazing a trail here, singing the praises of Feather, by Remi Bourgeon, which is included on the New York Times Best Illustrated Children’s Books of 2017 list, but it’s a book we’ve been falling in love with more and more every time we read it.

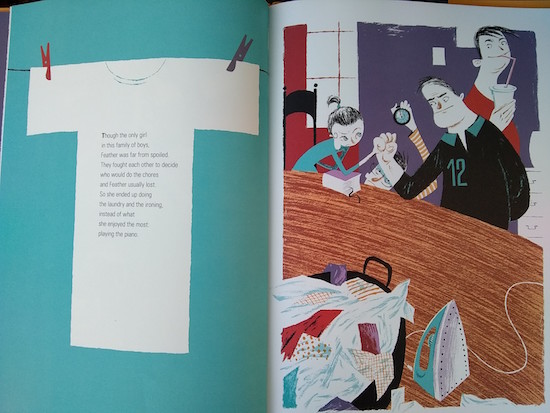

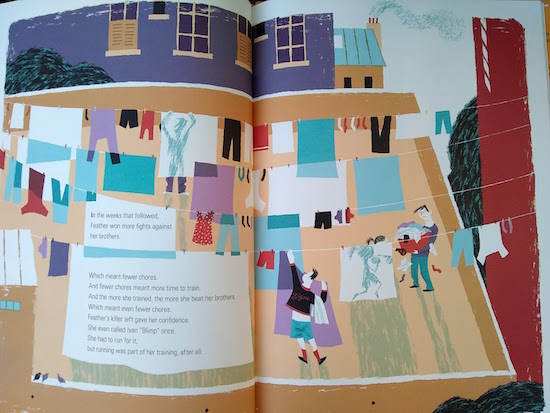

It’s an incredible exercise in minimalism, an entire novel so perfectly condensed into a few hundred works. Paulina is growing up in France, child of a Russian father who works all night driving taxis. Her mother, the reader assumes, has died, leaving Paulina the only girl in a household with three older brothers. She’s not just the youngest, but she is also the smallest—they’ve nicknamed her “Feather”—and when they end up fighting over household chores, she always loses, and ends up having to cook and do the laundry and she’s left with no time for her favourite occupation: playing the piano.

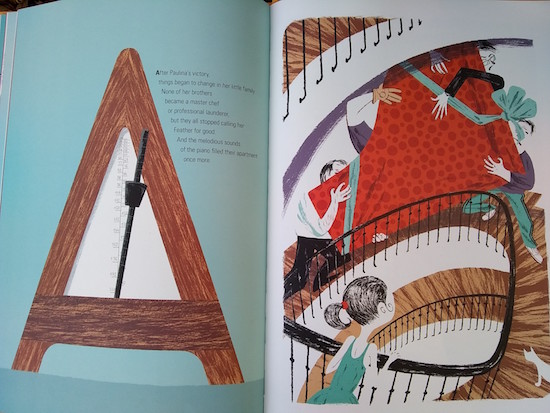

One day, after getting punched in the face and sporting a mean black eye, Feather announces that she’s quitting piano to take up boxing. No one can get her to change her mind, and she’s just as determined in her training as a fighter. Courgeon’s illustrations are fantastic, full of detail and action, and are so excellently married with the text in that the first letter of the first word on every pages is also a picture: see the L as the flexed arm below, the T in the t-shirt above, a J that is a cat’s tail dangling from the top of the piano, and an S that is a skipping rope. (And credit to translator Claudia Zoe Bedrick for making this work in English!)

As Feather devotes herself to training, her brothers are forced to take on a greater load of the household chores, but mostly just because Feather starts winning the fights over who has to do them. “Feather’s killer left gave her confidence. She even called Ivan ‘Blimp’ once. She had to run for it, but running was part of her training, after all.”

Before every match, Feather gets ready by reciting “the names of women who had bravely made a place for themselves in the world: Rosa Parks, Marie Curie, Nellie Bly, Anna Lee Fisher, Sally Ride… She always ended with Nina Simone, because she had played the piano too.”

The book’s climax is the moment before the big fight, when Feather discovers notes from her brothers and her father hidden in her boxing glove, cheering her own. Her father has left a photo of her mother with a note on the back: “We’re with you, Paulina! Love, Dad.”

She wins, of course. You knew she would. And things do change around their house—she’s learned the respect of her rough and tumble older brothers But the surprising twist in the story is that she gives up boxing after that, and goes back to piano. “Fists should be opened and fingers should fly,” she explains, the last illustration showing a grownup Paulina playing piano with a baby on her lap and a boxing trophy on display.

The book’s final image is a boxing glove in the endpapers being used as a vase for flowers, and I love that idea. This is a fantastic book with a strong feminist message, but like all the best feminist things that message is not singular. This is a fun engaging book first and foremost, but it will also leave its reader with questions and things to think about, and a million other reasons to reopen the book and start reading gain.

November 23, 2017

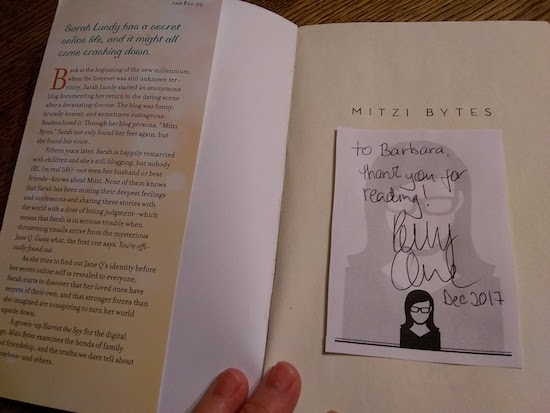

Mitzi Bytes in the World—and under the Christmas Tree

For a person whose book came out a whole season ago, I had a pretty busy fall doing bookish things, and I realized I’d forgotten a few of these here. The first was my event at Word on the Street in September, which was a day so overwhelmed with exciting things that I kind of lost my mind, but still. I did a fantastic event on literary outcasts with Jonny Sun and Shawn Hitchens, and our tent was packed and I had the very best time.

And in October, we had the most glorious weekend away in Stratford, taking in the goodness of that wonderful town and a showing of Treasure Island—but the whole reason we were there at all was for the Stratford Writers’ Festival. I arrive on Saturday morning and did my blogging workshop for a fantastic group of people at the library.

And then later that day I got to be on a panel on feminism with Scaachi Koul, which was hilarious and invigorating, and she was lovely and exactly as smart and biting as she in her book. It was a great conversation, and it was very cool to see Mitzi Bytes discussed in the context of Koul’s work and her book, and how both books informed each other. It was such an honour and a pleasure to take part in this event.

And I finally, I really think that Mitzi Bytes would make an amazing holiday gift for all your loved ones. (Of course I do!) If you’re going to be giving Mitzi Bytes for Christmas, drop me an email at kerryclare AT gmail DOT com and I will mail you Mitzi Bytes bookplates personally autographed to your gift’s recipient. Because books always make the best gifts and they don’t even require batteries.

November 22, 2017

The books I didn’t read

Last month I wrote a post called “Where do my books come from?”, whose title was pretty self-explanatory. And I am curious to explore the ideas within it further, beyond the wheres of my book choices to the whys. That I read Guidebook to Relative Strangers because two friends (one online, one in the park) had recommended it to me in the same week; I read My Conversations With Canadians after seeing Lee Maracle speak at Word on the Street. But before I get to the whys, I want to finally write down a post that’s been on my mind for awhile, a post about the books I didn’t read. Which requires me to underline again that I receive books in the post almost every day of the week from publishers, in addition to the considerable number of books I purchase from bookstores, meaning there are always inevitably going to be books I didn’t read. Some will filtered out by my own biases: books about inspirational dogs, YA books about dragons, middle grade and YA books in general (though there are exceptions), books without women in them, books about regional politics, and books about academic theory, and paranormal erotica.

It’s not so much that there is anything wrong with these books or these genres per se, it’s just that I have so many other books to read and if I’m going to have dismiss some it makes sense to dismiss the ones that don’t interest me. If I were paid to read widely, then one might argue I have an obligation to explore all the literary avenues, but this is my blog and anyone who comes here arrives expecting to read about the books I want to read, not the books I’ve read by obligation. And yes, I know I will indeed miss out on some wonderful books by dismissing many so categorically—but the sad fact of the matter that I’m still coming to terms with is that I can’t read all the books in the world I want to read, so I’m hardly going to worry about the ones that I don’t.

Which is not to say that I’m not obligated to expand my horizons, of course, or to look critically at the limits of my reading experience. Once upon a time, ages and ages ago, I realized I was missing out on books published by small independent publishers, and for a while especially sought these out—but then very soon after I didn’t have to do the seeking because the whole thing had become habitual. Similarly, about five years ago it occurred to me that I was mostly only reading books by authors who were white. I was fortunate that I had this revelation at the same moment so many other people did, because suddenly there seemed to be a bigger spotlight on Indigenous writers and writers who were people of colour and I didn’t have to go out of my way to find these books.

And can I just mention that the reason I want to find these books is not out of some demonstration of virtue or social obligation, but because it’s kind of weird to live in a world populated by people from all kinds of ethnic backgrounds and realize that you mostly only read books by people who are white? Think of all the stories and voices you are missing. I don’t want to be that narrow as a reader. I also happen to find those stories and voices very interesting—and so these are the reasons by books by Indigenous writers and people of colour are less likely to be the books I didn’t read.

On the other hand, I don’t tend to read books by men. I have to be very diplomatic about this. I have to be diplomatic about this because someone I know recently posted such a statement on Facebook, to which someone respond with an angry tirade they then deleted and then they unfriended her. Clearly, this is a sensitive issue. And I address this by stating that I have piles and piles of books to be read, and it’s not that I don’t want to read the books by men but that I want to read the books by women first (because I find them more interesting) and if I’m ever through with the books by women I’ll get to the men books—but this hasn’t happened yet.

Also, the other night I was posting flippant tweets about reading books by men, and then later I considered the authors whose works my tweets were dismissing and I felt a bit guilty for potentially hurting their feelings. AND THEN. And then it occurred to me that (I am quite sure) not a single one of these authors felt obligated to read my book (if you are a man and you read my book, I know exactly who you are and I am really grateful to you, and I can also count the number of you on my fingers) so I stopped feeling guilty after that.

So just say you are a woman, or a Black man, and/or you’ve written a book that’s not about an inspirational dog, which is to say that you’ve just made it into my sacred reading lair—what might compel me to stop reading your book once I’ve bothered to stop reading? Bad typesetting, for sure. A hideous cover—book design is important. Typos. Allusions to an artist or philosopher I’ve never heard of is another—I really just don’t want to read the book you’ve written imagining 19th century polemicist Tomas Niskanovich Pornakarsky as a squeegee kid on the streets of Saskatoon. Once a few years ago I stopped reading a novel on Page 7 because the main character noted that he’d begun to find older women attractive and subsequently became overwhelmed by feelings of dread (which is another reason I don’t tend to read books by men, by the way).

Two weeks ago, I stopped reading a novel because it was 500 pages long, all the women characters were ethereal, and I hated the book more and more with every paragraph—and I’d already read to page 200. It was a novel that was desperately trying to be Fates and Furies, which I must admit was also a novel that tested my patience as a reader, but I had such confidence in its author that I persisted. Not so much with its derivative.

Often I put down a book determining, “It’s just not for me.” This, honestly, is not the same thing as determining, “This novel is a piece of garbage” (which, of course, is another reason I will put down a book, but wouldn’t you?). Sometimes I see the literary merit of a book but I’m just not very interested in the project. Can I bear to suffer through 300 pages of this? Possibly an inspirational dog has bounded in on page 27, catching me unaware. Maybe there is also a child narrator, which I have a really hard time with. Or the book is written as a series of paragraph-long chapter vignettes, and I decided I’m going to have as much trouble focussing as the book’s author apparently did.

My terrible confession is this: there is an incredible correlation between the books I’ve started reading and abandoned for being not for me (or never bothered to pick up at all) and books that have gone on to be nominated for all the major literary prizes in Canada. I might have the very worst literary instincts in this country.

I tend to put books down if they feature a character whose best friend has died of cancer and that death has inspired main character to change the way she lives her life, particularly if I happen to have picked up this book when I am in the waiting period for biopsy results. Along those lines, I have never read The Bear, by Claire Cameron, because it came out while I was pregnant with my second child and terrified I was going to die of thyroid cancer, and so the premise of a book about a child whose parents die at the very beginning was too terrifying for me to contemplate. I have also never read The Crooked Heart of Mercy, by Billie Livingston, because it’s about a family whose child dies, and I seem to have turned into the kind of person who kinds such narratives too hard to ponder—but I think I am going to read it at some point, because I’ve heard so many good things about it.

I almost didn’t read Station Eleven, by Emily St. John Mandel, because I’d had a lot of trouble with her first book and Station Eleven was post-apocalyptic—but then I ended up loving it. I didn’t read Truly Madly Guilty, by Lianne Moriarty, when it first crossed my path because I’d read a dismissive review of it and thought it wasn’t worth my time, but then I read Big Little Lies and realized that Lianne Moriarty was a genius. So I’m not saying my system is infallible, but the point is that I did find my way to these books eventually, and more often than not I think my instincts are right about the kinds of books that work for me, and so I trust them. And why not? It’s not like there’s ever been a shortage of books that I am totally in love with.

I kind of insist on my right to not like a book, to hate a book even. To be uninterested in a book, or dismiss it without having read it. Because life is too short and the books are too long. I think this insistence has helped to me as an author to process and even appreciate those readers (I believe there were three and a half of them—poor souls) for whom my book was not their cup of tea. There really are so many books out there, and I’m glad that readers are free to plot their own ways through them, to pick and choose based even on the most arbitrary things. This kind of freedom is what keeps life interesting, and enables literary conversations to mean something when they happen.

November 20, 2017

Shut up, shut up, shut up

I’ve been thinking a lot about interviewing lately, mostly because I’d like to get better at doing them. Mostly because if I get better at interviewing, the proportion of time I spend listening to my own voice and wanting to die while transcribing will decrease, which is always a good thing. And because there’s a lot about being a better interviewer that is synonymous with being a better person in general, an ongoing project of mine. Becoming a better interviewer means becoming the kind of person that people want to talk to, which is always useful kind of person to be at dinner parties and other social gatherings (or so I imagine).

Before an interview I did last month, I asked a group of writers for any interviewing wisdom they might want to impart, and I received some excellent advice, including to go over your interviews very critically and apply that feedback to do a better job next time, and I think it really worked for me, because I did another interview on Friday morning which I’m about to transcribe now and there is a possibility I won’t want to die once while listening to my recording of it. It helped that the person I was speaking to was utterly fascinating and generous with her thoughts and ideas, of course, but it also helps that I really worked to obey the voice in my head commanding me, Shut up shut up shut up.

I am a pretty good conversationalist. And I am a downright superb monologist, for that matter, but that is very different from being a good interviewer, a good listener. Part of the problem is that I have to fight my reflex to crack a joke every time one seems readily available. Which that is also called interrupting. You don’t have to be funny, was something else I was telling myself on Friday morning, and it kinds of goes against my religion.

Not all my interviewing downfalls are symptomatic of my character flaws, however. It occurred to me while I was shutting up on Friday morning how much I feel compelled to interrupt as a kind of affirmation, an act of empathy. To say, Me too. Me too. I know exactly, and then proceed along a tangent with an anecdote to demonstrate just how much I do. I think the motivation here is genuine kindness as much as it is self-absorption, but it’s also such a faulty communication mechanism. Empathy has its limits, it does. Because we can’t ever really know exactly what another person is going through, and to suggest we can instead of taking the time and effort to genuinely listen and learn is ultimately counter to the project—if the project is connection.

And the project should always be connection.

November 19, 2017

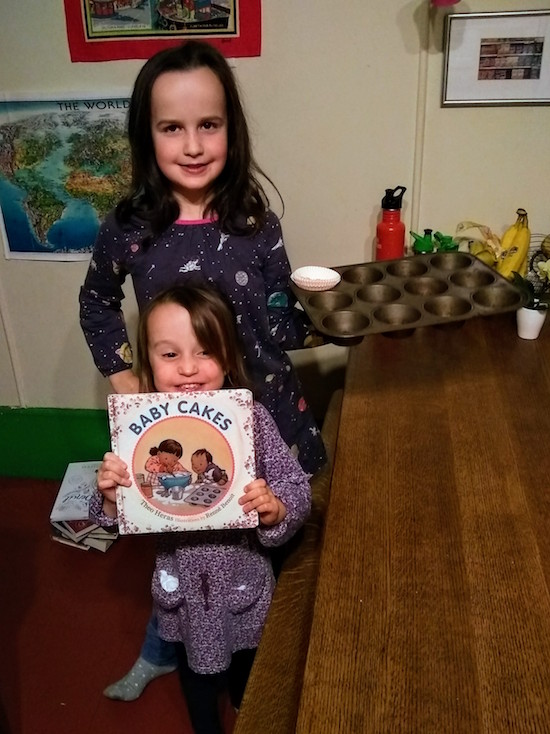

Baby Cakes, by Theo Heras and Renne Benoit

When Harriet was three-years-old, I read Bringing Up Bebe: One American Mother Discovers the Wisdom of French Parenting, by Pamela Druckerman, and loved it mostly because it affirmed all the things I already believed about raising children and therefore I got to feel sophisticated and European, which is always nice when you’re only Canadian. And what I remember mostly about the book, apart from the fact its author had previously published an article in Marie Claire about giving her husband a threesome for his fortieth birthday, was the chapter on baking, and the recipe for yogurt cake. (There was also a chapter on babies sleeping through the night. That chapter didn’t work for me.) French children, according to Pamela Druckerman, bake all the time, and thereby learn about fractions and chemistry, plus stirring and pouring and patience and not spilling things. All of which were things that I could get behind, and so we made that cake, and we made it over and over, in addition to so many other cakes we’ve baked in all the years since. And that I’ve still yet to lose the weight from my last pregnancy suggests Druckerman may have omitted an essential detail in her text, which is that French mothers possibly don’t eat the food their children bake. But then where’s the fun in that?

We have a photo of Harriet from the first time we baked together, sometime in the months before she turned two, and she’s standing on a chair wearing an apron and holding a wooden spoon, and I tweeted the photo with some kind of caption like, “Basically I only really had children in anticipation of this moment.” Because I also remember standing on chairs while wielding a wooden spoon, and have such visceral childhood memories of baking, and I wanted Harriet to have to her own. Plus I wanted cake, of course, and so we baked, but it wasn’t always easy. My frequent admonishments of, “Don’t put your hands in the flour,” “Don’t sneeze in the batter,” and “Goddamn it to hell, you’ve just poured vanilla all over the floor” usually went unheeded, and we began to consider a baking session successful if I’d kept my swear words to a minimum of three. Baking with kids was often not as fun as it was made out to be. But I persisted—in addition to math and chemistry, I told myself, my children were learning about human fallibility (mine!) and also expanding their vocabularies.

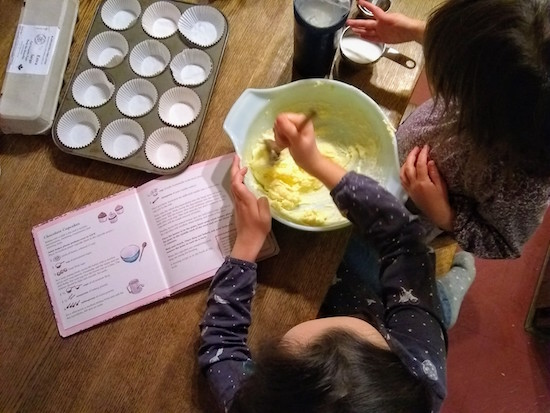

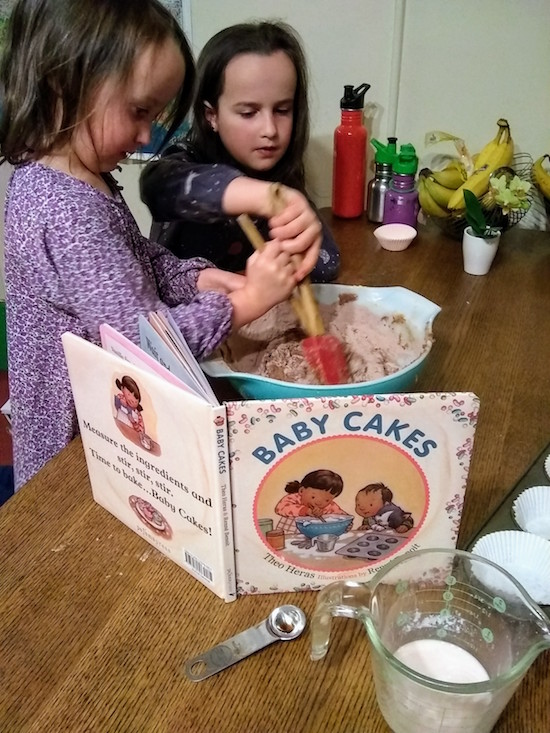

The very best thing about having children, however, (which is also the very worst thing) is that you basically get a new child every two weeks or so. Which is to say that everything changes, all the time, and the things that seemed impossible once upon a time eventually get to seem easy. Harriet sneezes in the batter hardly ever now, and when she and Iris sit down to baking they’re actually quite capable. And when I’d recently read Iris Baby Cakes, by Theo Heras and Renne Benoit, she’d declared, “That’s such a good book, Mommy.” Mostly because she’s obsessed with cupcakes, but still. Plus there was a recipe for cupcakes in the endpapers; I said, “We’ve got to make these.” And so on Saturday night, we did.

This book would make a great Christmas gift from 3-5-year-olds. With simple vocabulary, a brother and sister would together to make cupcakes (with the unhelpful assistance of their pet cat). The story lists the equipment necessary—”Here are a big bowl and measuring cups and spoons.”—and goes through the recipe, “Sprinkle salt, but not too much.” And “Creaming the butter is hard work.” And is it ever! The recipe inside makes for a nice extension of the book, bringing the story to life and inspiring the reader to try something new. That the brother and sister in the story bake together without the help of grown-ups (except for with the oven) inspires independence. Plus, the cupcakes were delicious. Obviously, I ate one. Because I am not French.

November 15, 2017

In the middle of a reno

The novel as a house is one of my favourite metaphors, and one I’ve used often to explain my experience of working with editors—the way they can open a door and show you that your house has a whole wing you never knew. But right now as I’m at work on my new novel’s third draft, I’m thinking of the metaphor in another sense: I’m in the middle of a reno.

Chapter Two, and a lot of the furniture has been moved move out, put into storage (i.e. into a word doc on my desk top). And we’re knocking walls down, putting in windows and skylights—and basements, ever digging deeper. Raise high the roof beams, carpenters! I have actually, literally, installed a hearth. Lifting up the floorboards to see what’s underneath them, and inside the walls—all the parts of the structure that have been present all along, just waiting for me to find them. The process is fascinating, almost mathematical, the way all the pieces have to fit together, the necessary strength of the structure underlining it all. Knock, knock. Is there integrity? Is this a supporting wall? And if it isn’t, would it matter if we ripped the whole thing down?

There is also a dumpster on the lawn, for all the inevitable detritus. Delete, delete. All the lines I wrote in order to understand what I was thinking, but now that I know, I don’t need them anymore.

November 13, 2017

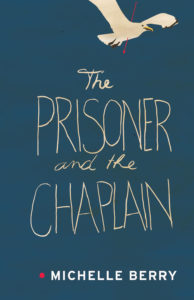

The Prisoner and the Chaplain, by Michelle Berry

An interesting thing was that I started reading Michelle Berry’s novel, The Prisoner and the Chaplain, on the night the clocks went back, which meant I ended up reading most of it on a day with an extra hour in it. The extra hour significant in light of the novel’s treatment of time, counting down the final twelve hours of a man’s life before his execution. Even for those of us for whom the future is not so limited, a twenty-five-hour day serves to underline how much every hour matters. And such a day is useful too, particularly when one is reading a novel as difficult to put down as this one is.

An interesting thing was that I started reading Michelle Berry’s novel, The Prisoner and the Chaplain, on the night the clocks went back, which meant I ended up reading most of it on a day with an extra hour in it. The extra hour significant in light of the novel’s treatment of time, counting down the final twelve hours of a man’s life before his execution. Even for those of us for whom the future is not so limited, a twenty-five-hour day serves to underline how much every hour matters. And such a day is useful too, particularly when one is reading a novel as difficult to put down as this one is.

The novel begins as part philosophy—a treatise on faith, belief, on the nature of self—and part bildungsroman. There are two men in a room, a prisoner who has committed a heinous crime and the prison chaplain tasked with being with the prisoner in his final hours. The chaplain is young, inexperienced. He’s only there at all because his mentor has become ill and no one else can do it. And the chaplain wonders if even he can do it, if he’s up to the task, considering his inexperience and also the violence in his own past. What will these hours make of him?

The prisoner though, he just wants to talk. To tell the story of how he got from there to here, and he begins with his childhood, his mother’s abandonment, his brother’s violence, his father’s alcoholism, his sister’s descent into addiction. Petty thievery leads to larger crimes, one thing leading to another, this story told in chapters interspersed with those set in the present, which is ever encroaching upon their limited future. And here the chaplain reflects on his own violence, the events leading up to it. How is he different from this man before him, the chaplain wonders? Why is this man and not another the one who deserve to die?

It’s as intense as you’d expect, this story, the intensity growing stronger as the hours count down, as the prisoner gets closer and closer to revealing his crime. I read this novel right after Alison Pick’s Strangers With The Same Dream, which was similarly intense and had overlapping thematic concerns (certainty being one of them) and on Sunday night I had such a troubled sleep, and the next book I chose from my shelf after that would have to be a slim little volume called Calm Things. But still, it is a testament to the novel and a mark of its success that it’s just so unsettling. It’s not every book that creeps into your head like that, gets right into your dreams.

By its conclusion the novel has also become a thriller, and it’s here one sees the connections between The Prisoner and the Chaplain and Berry’s previous novel, Interference, which was similarly genre-blurring and feature and underlying current of violence, a sinister edge. Contributing to the unease of The Prisoner and the Chaplain is that the prisoner’s story never quite lines up with the one the chaplain knows is on the official record, although he’d been warned about this by the warden. That the prisoner would try to get under his skin, to get him onside. And is this what has happened when the hour for the execution is imminent and the chaplain is quite sure the prisoner didn’t actually commit the crime he’s being punished for? Or is this really the case of an innocent man who’s about to die?

The novel’s momentum starts strong and just keeps going and going, and then the ending packs a wallop. Make sure you set aside a good block hours before you start this book, because you’ll be needing every one of them.