December 14, 2018

Santa Never Brings me a Banjo, by David Myles

During The Most Wonderful Time of the Year, it can be easy to forget that Christmas is not a season of light for everybody, that those who are struggling can find the holidays particularly trying—and in his song-turned-picture book, Santa Never Brings Me A Banjo musician David Myles gives voice to one boy’s particular plight. Because, see, all he wants is a banjo, a simple request. And year after year, Santa fails to deliver, the boy’s hopes piqued by banjo-shaped packages that turn out to be something entirely different—a fishing net, a unicycle. But not a banjo to be had.

It’s a story of persistence, I suppose. We liked this book a lot and it’s made a great, non-cloying, and original addition to our Christmas library. A story of wanting and yearning and longing and the sweet anticipation of Christmas morning that has always been my favourite part of the season. It’s a story about one child’s love of music, and wishes finally coming true, and also a catchy melody that will get stuck in your head—with the music included, along with the chords. So you can play in on your banjo when all your dreams are realized.

December 13, 2018

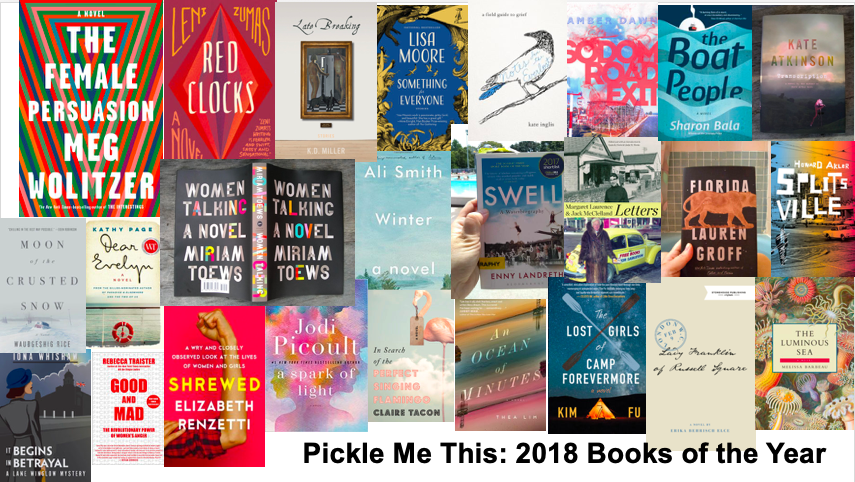

2018: Pickle Me This Books of the Year

- The book that was a balm for my broken spirit after my democratic rights were recklessly undermined by an authoritative government during the recent municipal election

- Not the best Kate Atkinson book ever, but even an okay Kate Atkinson book is better than most books. I LOVED IT.

- A book about who gets to be us and who gets to be them, and how we refuse to learn the lessons of history over and over again.

- So gorgeous and riveting—and so few books manage to be both.

- The book I was reading for six months, and could have kept reading forever

- There was no better summer read than this one.

- For those who know that the inner life of a woman is the most fascinating place of all for exploration

- Lord of the Flies turned inside out—and fascinating in terms of narrative

- Lauren Groff has never managed to not be excellent. I love her.

- Essential reading for anyone who has known grief, and those who love them.

- The history of feminism through the history of swimming? Okay!

- Hauntingly beautiful. So happy to see this book get the love it deserves

- Linked short stories inspired by Alex Colville paintings! And they’re amazing.

- Still not over those stories. Lisa Moore defies all expectations here, except to write really really well

- My first Jodi Picoult novel—and I loved it

- The book we need right now

- The book I’ve been recommending to everyone

- The story of a marriage and a century in a single book. SO GOOD.

- I can’t wait until Spring.

- A funny, poignant and original exploration of family life

- This book is hard work, but it pays off, and is full of quiet profundities

- My new manifesto.

- Discovering the Lane Winslow Mysteries was one of the best parts of my year. I LOVED THEM.

- Oh. feminism, and all its waves. Wolitzer is not afraid to show how complicated and glorious is the tangle

- Imagine a world where women weren’t permitted reproductive freedom. Sounds a bit far-fetched…

December 12, 2018

More on Year End Lists

When I say I posted the above tweet last week in a tongue-in-cheek fashion, I am mostly lying because I was quite serious. In fact, I think I was even more annoyed this year than I was last year when my book did not receive significant acclaim as one of the great literary events of 2017, which is totally stupid, but also underlines that it is never not stupid to be furious that your book has failed to cause an earthquake, that publishing a book turns out not to be a catapult after all. The feelings are legitimate, but these are also feelings that one must necessarily pack away so one can carry on, because what a lucky thing to even publish a book in the first place. Get over yourself, is what I mean.

Although it’s easier to be so magnanimous when your book did not actually, this time, qualify for all those year-end lists it failed to turn up on. Also when you have spent the second year of your novel’s life receiving sweet and not infrequent reminders that the life of a book is long—my book was a Sweet Reads pick in January, I signed copies at a literary festival this fall, on random Saturday nights someone tags their cover in an Instagram post. And finally it’s really easy when you are in fact author of at least three of those year-end lists—the most important ones, in fact. Which possibly provides a little bit of perspective on how arbitrary* the whole process is.

*Which is to not undermine my authority as a literary critic. My year-end lists are amazing.

I have loved so many books this year, and I actually love year-end book lists because it’s one of the few ways that we know how to make books part of a wider conversation. (We need to think of more of these ways. I recently read a statistic that put the percentage of adults who read for pleasure in the single digits, which is shocking. Book clubs are another way, awards lists too, and Canada Reads, and I think those of us who love books have to try harder to make books and reading relevant and find places for them in people’s daily lives.)

So that the real challenge then in coming up with year-end lists for Chatelaine, 49thShelf (which was done in concert with my colleagues), and here at my own blog was not having the lists go on forever. 49thShelf, at least, had the restriction of being Canadian books, and we tried to focus on independent publishers and books we’d featured on the site in order to showcase our content. The Chatelaine list was to be more marketable and broadly-appealing, with each book needing to be markedly notable beyond the fact that I just liked it. Which brings me to the Pickle Me This Books of the Year list, which will be up this week or early next, which is thoroughly my own creation, and which is probably the hardest of the three lists to turn up on, meeting a rigorous standard that I can’t properly articulate, and I don’t even have to.

I guess in some ways, year-end lists are a little bit redundant. The books that didn’t matter to me are the ones I never read in the first place, or else the ones I read in private because I’d decided to keep my opinions to myself. I’ve been keeping a list of My Favourite Books of 2018 (SO FAR)—49thShelf, so Canadian titles only—and while not all these will be on my whittled down final list, they all are certainly contenders and I recommend them heartily. I’ve also been recommending books all year on the radio too, and stand by these picks. Basically I’ve been drowning in a delicious sea of wonderful reading, and these lists are my attempt to find a door to float upon. Also. and it’s distinctly possible, that it all comes down to the fact that I’ve got a list-making compulsion.

December 11, 2018

Ode to a Parkette

That the park is being bulldozed doesn’t affect my daily life in the slightest, because we don’t even go to the park anymore, and it’s mid-December so we wouldn’t even if we did. But it’s at the symbolic level where it gets me, this park where I spent some of the best years of my career in motherhood, where I came of age as a mother, so to speak. This park where certainly things have changed over the years—the mysterious disappearance of the bumblebee bouncy toy, leaving the ladybug all alone; the tree in the north end was cut at some point; the tree in the south end that was planted to honour somebody’s grandmother, where the leaves were always changing, and falling, and the ground would turn from ice to mud to summer. Where my children changed—they don’t eat the sand anymore, for example—and certainly I did, but the fundamentals stayed the same. The bench on the east side that was missing a slat, and the boarded-up house behind the baby swings that made all of Harriet’s baby photos look like she was swinging out front a crack den, and the little hill on the south side which was perfect for tobogganing on days when you just don’t feel like climbing big hills.

The people were always changing too, and in the beginning there were none of them, just Harriet and me, and we went to the park since I couldn’t think of anything else to do with a baby, because there are only so many hours a day you can spend at the library. Even though parks aren’t really ideal for babies, other than the swings, and pushing one of those for hours is boring, although less so when you do it while reading a book. I remember Harriet falling face-first in the sand there once, and how she got up licking her lips. Our baby days at the park were as aimless as life in general then, but then she got a bit bigger and things got a bit better, and one of the all time greatest afternoons of my life was spent at that park when Harriet was two and she was content to pretend to be driving the jeep toy for hours, and I sat sprawled across the backseat and read an entire book cover to cover. (It was The 27th Kingdom, by Alice Thomas Ellis.)

It was around this time that I’d met my friend Nathalie, whose children were older than mine and who was blazer of many paths I would follow, chief among them Huron Playschool. When Harriet was two, she urged me to register, but I didn’t make enough money at that time to justify it. Still, when Harriet and I were in the park, I’d seen Nathalie’s son in the park with his play school class, and consider the impossibility of Harriet ever being as old as that. And by the time she was three, she would join him there, skipping off down the sidewalk. Every day at playschool, the children played in the park, and it was where I’d pick her up at the end of the morning. I remember sitting around the sandbox with Harriet during her first week of school, and also I was pregnant, but nobody else knew it yet, and the women I was hanging out with there would eventually become my friends. All those hours we spent in the park, on playschool co-op shifts, and also after, because Harriet had stopped napping and we had no reason to hurry home, and it was spring, so early, but we took our shoes off, and buried our feet in warm sand.

All the children were there. Among the trees, in the arms of statues, toes in the grass, they hopped in and our of dog shit and dug tunnels into mole holes. Wherever the children, their mothers stopped to talk.” –Grace Paley, “Faith in a Tree”

I wrote a blog post about that spring we spent at the park, about the woman who were so kind to me during my second pregnancy, and supported our family in incredible ways, and comforted me through difficult times and promised it would all be okay. Most of these women I see rarely now, if ever, and our children would not know each other if they met, but they were there for me at such a pivotal moment, and in my memory of them all, the sun is shining always. Although I’d read Grace Paley wrong, I’d discover a couple of years later. What a thing—the most shocking revelation of my literary life. “I really thought that they’d been it, those mothers in the park. I really had thought she meant that this, the mothers stopping to talk, was the most important conversation. But it wasn’t, her revelation. Faith needs more than that, chatting women lounging in trees. The world needs more than that, at least if we ever expect to do anything about it.”

The first time I took both my children to the park alone, Harriet got stung by a wasp while I was breastfeeding on a park bench, which was not the most auspicious start, but we found our groove, and as a mother I really found my stride.

There’d be one evening in the years to follow when a friend and I would have pizza delivered to the park, and we’d all eat dinner there, in lieu of home and tables, which meant I was a long way from being that woman aimlessly pushing her baby in a swing, and I didn’t even get to read anymore, because there was usually somebody I wanted to talk to.

Eventually, the park became more special occasion than every day, because daily life became more structured. We’d meet up at the park on weekends and holidays, and during the summer of 2016, there were picnics and potlucks and always pie. I’d see mothers who were there with their babies, and I was a million miles away from them, without a clear idea exactly of how I’d arrived here, although the place was the same. I had two kids who could conquer the big climbers, and they’d fly down the steep slide, and I wouldn’t even have to watch them. I had officially retired from pushing swings.

Last summer, our good friends moved out of the neighbourhood, so we haven’t had pies in the park for awhile, and that the city decided to bulldoze it now doesn’t seem so incongruous. (We did enjoy walking through the park in the autumn, however, on our way home from school, when the park was being excavated as part of a project by the university’s archeology department. Old maps had indicated there had been dwellings on the site, and significant finds included bricks and teacups.)

The park is going to be redeveloped along with the expansion of the University of Toronto Schools next door, who are going to be building a facility underneath it, some of the playground equipment being temporarily located to the vacant lot across the street in the meantime. And by the time it’s all finished, my children will likely be too old for parks at all—who’d ever have thought it? And the derelict house on the other side of Huron is finally being developed, after more than a decade, at least, so maybe we can definitively say that absolutely nothing stays the same, which is the point of cities, and parenthood, and everything.

December 10, 2018

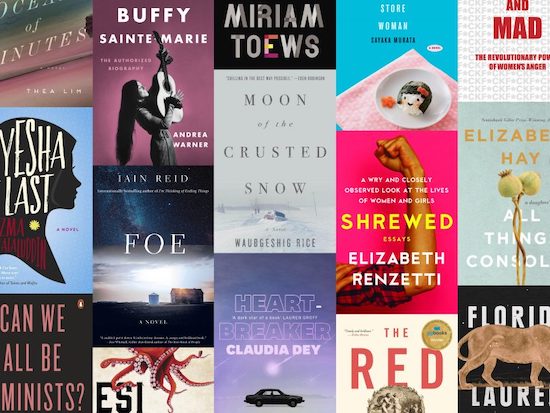

Chatelaine: Books of Year

I cannot overstate the pleasure I had being tasked with creating Chatelaine’s 2018 Books of the Year last, and how pleased I am with how it turned out. You can read the whole list here. And lucky me, I also got to help create the Books of the Year list at 49thShelf—there is definitely some overlap. And stay tuned for the Pickle Me This Books of the year list, coming up sometime later this week.

December 7, 2018

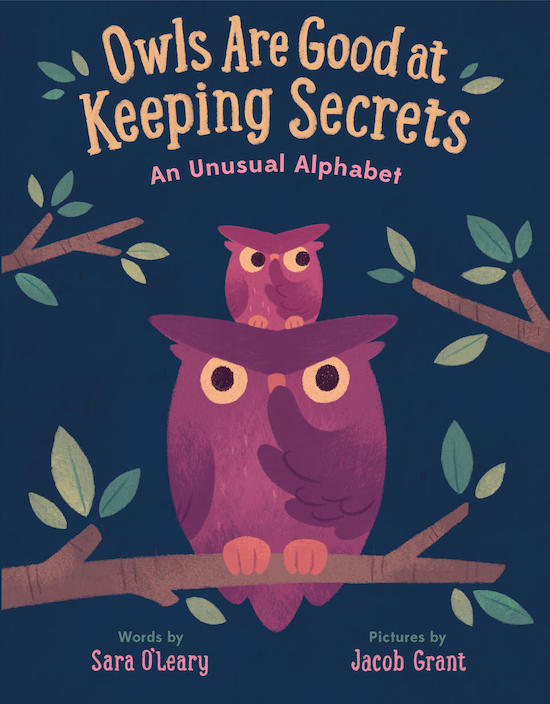

Owls Are Good at Keeping Secrets, by Sara O’Leary and Jacob Grant

One of my favourite kids’ books this year, a book with a wonderful premise and an execution just as good, is Sara O’Leary’s latest picture book, illustrated by Jacob Grant, the fun, clever and adorable Owls Are Good at Keeping Secrets—and of course they are! It just makes perfect sense, along with “Elephants are happiest at bath time” and “Jellyfish don’t care if you think they look funny when they dance.” And Z is my very favourite of all the alphabetized animal facts appearing in this whimsical abecedary, but I’m not going to tell it here, because that would be a spoiler. Of course, “Raccoons are always the first to arrive for a party,” but did you know that “Narwhals can be perfectly happy all alone”? And just wait until you get to U, which I’m going to let you discover by yourself, but I’ll trust you’ll find it as delightful as I did. The whole thing is good, O’Leary’s pitch perfect character details enriched by Grant’s illustrations, which manage to be cute and stylish at once. Even those who know their ABCs are likely to find this book absolutely enchanting, so while it’s an excellent pick for a Christmas gift for that someone little on your list, it will go over well also for those who are a little bit taller.

December 5, 2018

New Books on the Radio

I just can’t stop with the 2018 new releases, but one after another continues to wow me, so I’m very pleased by the opportunity to talk about five more of them this morning on my CBC Ontario Morning books column. You can listen again here—I come on at 41.30.

December 3, 2018

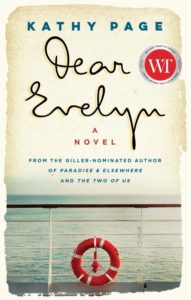

Dear Evelyn, by Kathy Page

Dear Evelyn, by Kathy Page, is a novel so good that last night I was full of nostalgia because it had been a whole week since I was reading it. And I was reading a very good novel last night too, but still, I was sorry to have been a whole seven days away from the remarkable experience of having been absorbed in Page’s award-winning book, which I read in two two-hour sittings. It’s the story of a marriage, the story loosely inspired by letters between Page’s own parents, some of which actually appear in the novel, making authorship an interesting collaborative endeavour. Beginning with the birth of Harry Miles, who grows up between the wars in London, the reader aware of the inevitability of his trajectory toward battle himself. But first, Harry meets Evelyn on the steps of the Battersea Library, and they fall in love with the same urgency as the world’s preparation for war, another kind of unreality. They spent most of the first years of their marriage apart, as Harry takes part in training and departs for war in North Africa. Seemingly-pivotal scenes—their wedding, Evelyn’s first pregnancy, the birth of their daughter—take place outside the narrative while Page focusses on the quotidian instead, the ordinary dailiness that Harry so longs for when he is away at war and longing for his wife.

Dear Evelyn, by Kathy Page, is a novel so good that last night I was full of nostalgia because it had been a whole week since I was reading it. And I was reading a very good novel last night too, but still, I was sorry to have been a whole seven days away from the remarkable experience of having been absorbed in Page’s award-winning book, which I read in two two-hour sittings. It’s the story of a marriage, the story loosely inspired by letters between Page’s own parents, some of which actually appear in the novel, making authorship an interesting collaborative endeavour. Beginning with the birth of Harry Miles, who grows up between the wars in London, the reader aware of the inevitability of his trajectory toward battle himself. But first, Harry meets Evelyn on the steps of the Battersea Library, and they fall in love with the same urgency as the world’s preparation for war, another kind of unreality. They spent most of the first years of their marriage apart, as Harry takes part in training and departs for war in North Africa. Seemingly-pivotal scenes—their wedding, Evelyn’s first pregnancy, the birth of their daughter—take place outside the narrative while Page focusses on the quotidian instead, the ordinary dailiness that Harry so longs for when he is away at war and longing for his wife.

And long for her he does, resisting temptation from other women when he’s far from home, and when he returns and settles into civilian life, the attraction between them is still strong. It’s not that this is a love poorly thought out, marry in haste, etc, but rather that life is long and love is complicated. And what is so astounding about the novel is how Page manages to show that complicatedness without compromising either of her characters. She shows how love and marriage can turn into something else as husband and wife continue to become more and more themselves as they age. It’s not that Evelyn changes—it’s that she never does. That strong personality that Harry continues to admire in his wife for so many years becomes a force that eventually pushes him out of his home, and the force is devastating—and yet he still continues to love her. And Evelyn herself, who is indeed herself but to a fault, and how her character traits borne out of struggle and deprivation during her childhood eventually leave her utterly alone. No wrenches need be thrown into this plot line, is what I mean. Or maybe what I mean is that that’s just what life is, a wrench. And characters themselves are just along for the ride, for better or for worse.

Dear Evelyn has a wonderful, effortless sweep, moving its characters from their hearty youth on to their nineties, including just the right details to show how the world is changing around them. Here, the novel benefits from Page’s experience as a short story writer, which is reflected in the novel’s episodic structure, the ease with which it moves from scene-to-scene and accumulates story without becoming bogged down. Short story writers are expert at efficiently fitting big ideas into small packages, which is how—in just 300 pages—Page is able to contain a century; two wars; two fully realized, flawed and complicated people; a rich and tumultuous marriage; so much love; and the pride, rage and resentment that keeps so much from ever being properly expressed.

November 30, 2018

The Zombie Prince and Mustafa

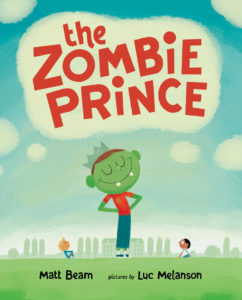

The Zombie Prince, by Matt Beam and Luc Melanson

The Zombie Prince, by Matt Beam and Luc Melanson

The first time we read The Zombie Prince, I was entranced by it, its puzzles and strangeness, how curiously it was framed, but the rest of my family weren’t so into it. “I didn’t get it,” they said, but I insisted, that this was a book that was special, that this was a book about boys and their feelings and the powers inherent in being sensitive. So we read it again, and they started to get it, liked the book as much as I do. I book that invites plenty of questions, which is why reading it again and again is worthwhile. “Why did Brandon tear up the flower?” I asked them tonight, and they speculated. This book isn’t breezy and is not a one-off, and runs the risk of being just a bit too subtle, but the illustrations are fun and appealing and the ideas of zombies and vampires are attractive enough to make a reader pick up the book a second time. This is a book with undercurrents, and the discerning reader will be able to put the pieces together. The discerning older reader will also be able to understand the implications of Brandon’s classmate having called him a “fairy,” and that this is a story with big implications. I appreciate its lack of obviousness, and that this is a book about boys and feelings that isn’t cheesy, or preachy. It’s expansive, like all the best books are, and isn’t afraid to ask its readers to think.

*

In her latest picture book, Marie-Louise Gay moves from her worlds of flying cats and a brother and sister in bucolic idylls to a different kind of reality, although it still comes with her characteristic whimsy. The title character in Mustafa is a young boy who has moved with his family away from an old country he still dreams of. “Dreams full of smoke and fire and load noises.” Lonely, he plays alone in the near near his new home, and takes in his new surroundings—shiny red bugs with black spots on their backs, trees whose leaves mysterious turn orange and red. “He sees two small animals jumping from branch to branch, They bushy tails wave and curl in the air. They chatter like monkeys.” There’s also a girl who walks a cat on a leash, and Mustafa is fascinated by all of it, but the girl in the particular because he fancies a friend. He asks his mother if perhaps he’s invisible. ‘”If you were invisible, I couldn’t hug you, could I?” answers his mama.’ But then one day the girl gestures for him to follow her, and they go together to watch fish in the pond. And Mustafa doesn’t feel invisible anymore, which makes for a really nice story about a refugee’s experience, but also an interesting exercise in seeing our homes from other people’s points of view, what we all look like from the outside, and how much it means to be invited in.

November 29, 2018

Gifts

There comes a point when one’s books enthusiasm reaches a certain height at which people just stop giving you books altogether. Because you’ve probably read it already, or if you haven’t, there’s a good reason why not, and either way, you’re probably so overwhelmed with books already that you’re hardly in need of another. And I lament this, the loss of books wrapped up with a bow, because books have always been my favourite gifts to receive. But at the same time, yes, I probably have already read it, or there’s a good reason why I never did. Because part of being a books enthusiast is possessing a very defined sense of what you don’t like too, for better or for worse.

There comes a point when one’s books enthusiasm reaches a certain height at which people just stop giving you books altogether. Because you’ve probably read it already, or if you haven’t, there’s a good reason why not, and either way, you’re probably so overwhelmed with books already that you’re hardly in need of another. And I lament this, the loss of books wrapped up with a bow, because books have always been my favourite gifts to receive. But at the same time, yes, I probably have already read it, or there’s a good reason why I never did. Because part of being a books enthusiast is possessing a very defined sense of what you don’t like too, for better or for worse.

So I relish those rare occasions where it all works out like serendipity, like the time my friend Jennie gave me Catherine O’Flynn’s What Was Lost after I had my first baby. It was one of the best gifts I’ve ever received, an acknowledgement of my identity as a person who was not only a mother, who still deserved something for herself, and could retain an element of who she was before the baby came. Also, because when somebody gives you a book, they give you a world.

At Blue Heron Books in Uxbridge, they’ve had mystery books wrapped in brown paper so that the costumer doesn’t’ know what they’ve got until they’ve bought it. Risky indeed—but then that was how I ended up with Herman Koch’s The Dinner a few years ago, a book I would never have bought on my own terms, but ended up really appreciating.

It was such a good experience that not long ago when I ended up in another bookstore (that shall remain unnamed) I was eager to lay down some cash for another mystery book. And once I bought the book, I was reluctant to even open it, for the mystery to be solved, for the anticipation was actually the best part: what was I going to get? What unknown world was I about to discover? And so imagine my disappointment then when I finally unwrapped my package and the book turns out to be The Fucking Pilot’s Wife by Anita Shreve, an Oprah’s book club pick from 1998, and I think I even read it then, but have no memory of it. A book that every single second-hand bookstore on the planet has at least twenty copies of, willingly or otherwise, and the only way to get anybody to buy them is to wrap them in brown paper. They saw me coming from miles away…

My faith in bookseller picks was restored a couple of weeks ago, however, when I picked up Let Me Be Like Water, by S.K. Perry, purchased in the summer when we visited the wonderful A Novel Spot Books in Etobicoke. It wasn’t wrapped in brown paper, but it might as well have been, because I knew nothing about it, but it was one of their picks of the year and I mostly bought it because they are very good at selling books there—they made it hard to say no. And then a few weeks ago after a reading rut, I finally picked it up, and I loved it. I was reading it on the Saturday morning and for some reason my paper hadn’t been delivered, and I didn’t care, because it meant I could read the novel all morning while I drank my tea and the sun poured into my kitchen. A book it took an expert reader—a bookseller—to connect me with. A kind of magic indeed.