January 11, 2019

I think your bullet journal is stupid.

Slightly insulting confession: I think your bullet journal is stupid. I’ve always felt one could get her shit done way faster if she just does it rather than mapping out a plan to do so in especially decorative ways…but then I have really terrible handwriting and always lose my good pens, so I would think that, wouldn’t I. It’s also possible that I’m jealous of your bullet journal, because if I had one, if would probably look like my grade nine math book. And that I wanted to write a provocative headline to get you to read this post.

Which is unfair, kind of, and I also don’t really know what bullet journals are, except that people share images of theirs on Instagram (and I swear I once read a post where a person was complaining about how difficult to was juggle all seven of the bullet journals she maintains, which seems pretty obvious). I’ve also been very fortunate in that I’ve not really required lots of strategizing in order for professional opportunities to happen for me. This spring marks ten years since I quit my job to become a freelance writer, which is something I did without any of how to make it work. It seemed slightly scary at the time, but I was also caring for a new baby, which was ten times more terrifying, and my professional life really did seem to require less maintenance in comparison. So if you asked me now to recommend a route to making a living as a writer based on my own experience, my advice would be mainly: wait for people to email and ask you to do stuff. NOT HELPFUL. (Note though that nobody’s going to do that if you’re not chipping away at building your blog oeuvre, which would these days be considered “building your profile,” but I wasn’t thinking in those terms, which is probably why I was even enjoying what I was doing.)

Part of the reason I’m also resistant to bullet journals is because they seem to be part of the online entrepreneurial culture that I’ve been resisting with all my heart and soul. The kind of culture where you use hashtags like #GirlBoss and #SheHustles, and sell skincare products via a pyramid scheme, and it’s so entrenched in capitalism in the very worst way, and for most people is a dream that never comes true regardless of the hustling. I was once trapped on an airplane full of women arriving at a multi-level marketing conference, and as we were stuck on the platform, the woman beside turned and said, “So: what’s your Plan B?” And I wanted to die and there was no escape, and sometimes the internet in general feels a little bit like that.

And it’s the opposite of everything that, for me, is fundamental to blogs and online connection. It’s about human voices, not selling products. It’s about telling stories, being a human, not being a brand. My blogging courses have always been defiantly anti-marketing, anti-strategy. Don’t target your audience. Don’t outline your goals. Instead, make it up as you go along. Figure it out and grow in the process. Dare to get lost, and then report back from the place you ended up. My blogging advice was never for people who wanted to grow their audience, but instead for people who wanted to write a blog that could serve them and be sustainable. And while these days I feel like I know less about blogging than I ever did (not necessarily a bad thing— ‘It’s the best possible time to be alive, when almost everything you thought you knew is wrong.’ —Tom Stoppard, Arcadia), I still believe in all that. A blog, like all the best things, is a wild thing, and should refuse to be tamed with plans and bullets.

And yet. I know that while this is true, I also know that part of my resistance to being more strategic and entrepreneurial in approach to my career is that I am afraid any other approach might end in failure. When your aim is to get lost, it doesn’t really matter where you are, but when you’ve got a plan, a goal and a strategy, and well, if you fall flat on your face, people are going to know about it. But something else I’ve learned from blogging is that sometimes being afraid of something is the very best reason to go there.

But then I start to worry again—and of course I am overthinking this. To be a successful blogger is to have made a career out of overthinking things. But I also think that 75% of the nonsense people are peddling online in terms of empowerment and entrepreneurship is absolute nonsense. I probably wouldn’t even be writing this post right now if it weren’t for these sponsored posts I kept coming across on Instagram by this woman—who I hadn’t even followed because she was way too much of a shallow marketing shill—about how I can grow my business via Pinterest. Which at first I dismissed as meaningless to me and irrelevant to my interests…but then at a certain point I thought, “Gee, maybe I should sign up for her free webinar!” And there it is: I have brainwashed. The moment I consider engaging with anything called “webinar,” it’s all over. Next up, I’ll be hash tagging #bossbae. It’s like a cult, and I don’t want to join it.

But I also know that I could certainly use a little direction, professionally. How many more books could I sell, followers could I get, opportunities could I receive, readers I could find, if I set out with intentions of being more deliberate in these areas? If I gave any considerations to being deliberate at all, instead of wandering, exploring, making it up as I go along. I’ve got a lot to show for ten years of approaching things in that direction, but aimlessness comes with its own wasted energy. I’m not saying I want to hustle, but surely there is some way we can meet in the middle.

Today I listened to Amanda Laird’s Heavy Flow Podcast with Kelly Diels on “resisting the Female Lifestyle Empowerment Brand,” which articulated a lot of my discomfort on this topic. Sarah Selecky does much of the same in her novel, Radiant, Shimmering Light, which surprised me when I read the book because Selecky herself has been so successful with an online business, and yet she’s also able to critique it in a really pointed way. I still don’t remotely know what I think of anything of this yet, but I’ve decided to find out by setting three professional goals for this year relating to developing my career. Which is really scary, actually, but also exciting, and I’ll keep you posted—and if I get lost, at least I’ll have something to report back on.

January 11, 2019

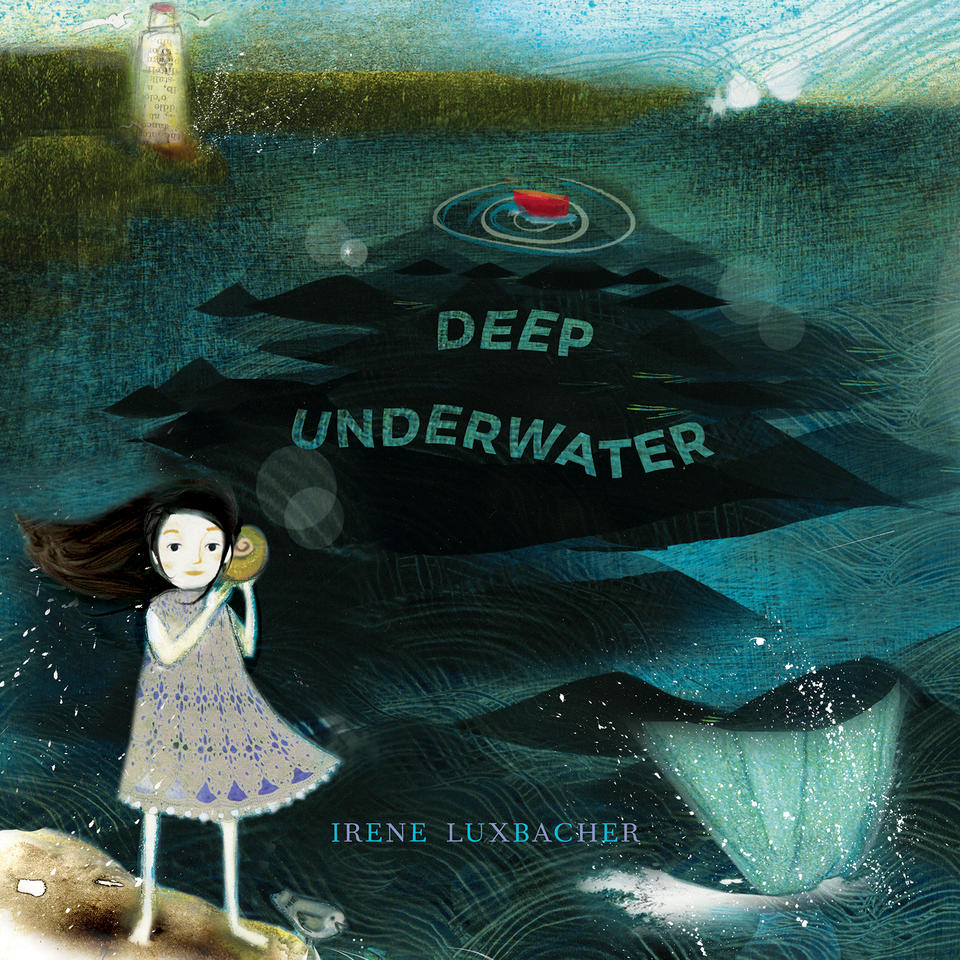

Deep Underwater, by Irene Luxbacher

I love Irene Luxbacher’s playful collage illustrations, and they really shine in Deep Underwater, her latest picture book. Shine literally even, because the cover features sparkles. It’s the story of Sophia, who lives by the sea and knows its secrets, and takes the reader on a journey deep underwater to share what she knows. “Deep underwater, tentacles, antennae and teeth disappear into darkness…and an abyss becomes a bottomless pit of possibilities.” Full page spreads to get lost in, with urchins, and anemones, jellyfish and seahorses. Sea turtles, starfish, sardines, and a submarine. A sunken ship where “lost treasures wait silently, patiently hoping to be found.” Sophia tells us, “Deep down, I never feel alone,” contemplating her reflection in a handheld mirror, and we see the mermaid that she is in her mind, and really, who can’t relate?

January 9, 2019

Escape Room Reads

I’ve been thinking lately about how grateful I am to everyone who has never invited me to an escape room party, and I was thinking this even before the story about the five Polish teenagers who died while trapped in an escape room facility that caught fire. There are few things I would like to do less than visit an escape room, and if I was ever forced into such an endeavour, I’d simply bring a book and read in a corner until it was time for me to go.

I’ve only ever encountered an actual escape room in fiction once before, in the story “Prize” in Jessica Westhead’s collection Things Not to Do, in which a couple of would-be entrepreneurs decide to get into the industry. “Allen works in data administration and I’m currently a cashier but I have my diploma in business communications so we’re already in an advantageous position, combined-projected-earnings wise.” Things do not go well, however, and the story is creepy sinister in a way that I now imagine all escape rooms actually are, which only underlines my aversion. No, I would definitely prefer to read a book…and the two escape-room-esque novels that I’ve read in the past week have only made this feeling stronger.

The first was Nine Perfect Strangers, by Lianne Moriarty, who has not disappointed me ever since I first read Big Little Lies, and then Truly Madly Guilty and What Alice Forgot. Moriarty is a master of compelling plots, suspense, and richly textured characters…but I will admit that this novel let me down just a little bit. About nine people who show up at a remote wellness spa, run by a woman who just might deranged, and at one point they really do all get locked in a room and it seemed very contrived and unnecessary, which is nothing I’ve ever said about a Lianne Moriarty novel before. The problem was structural—each of her characters has an incredible backstory, and there is humour and pathos, and each individual story manages to be really evocative—the has-been romance novelist who’s just been swindled in an online romance scam, the family trying to move on after the suicide of their eldest son, a young couple that’s drifted apart after their lottery win, washed up athlete whose life seems meaningless, woman whose husband has ditched her for a newest model, and the startlingly handsome man whose boyfriend wants them to have a baby, but he’s having none of it. Each of these characters should have been given a novel of their own, but to toss them all into one book like a grab-bag just seems wasteful. I enjoyed most of the book well enough, but close to the end I was really frustrated, as though this was plot for the sake of plot (like an escape room, no less) instead of a story. But by the end Moriarty had managed to tie it all up in such a way that my feelings toward the book were almost warm again, but still, this was not my favourite. Which is not to say that I’m going to give up my vow to read everything Lianne Moriarty ever publishes.

I had the opposite reaction to The Seven Deaths of Evelyn Hardcastle, by Stuart Turton, which I gave to my husband for Christmas and read when he was finished it. (I know what I’m doing when it comes to giving gifts.) He’d really enjoyed it and I was looking forward to appreciating for myself, and was disappointed to find the beginning a bit frustrating. It wasn’t bad, and the pace was fast, but I just wasn’t sure why it was supposed to be interesting. The way I suppose I’d be if I ever actually did visit an escape room, having to listen to all the rules and wondering why I needed to bother. Wasn’t this supposed to be fun? But it was, very quickly, Turton’s bestselling first novel that has been described as Agatha Christie meets Black Mirror. The narrator wakes up in a body belonging to a guest attending a party at a crumbling stately home where that night there is going to be a murder, and it’s up to the narrator to figure out what’s happening, and before he does he will wake up in the body of a variety of different party guests, and live the same day over again. I really liked this book, and enjoyed the twists and surprises and—except for one bit in which the twists comes because the narrator has withheld vital info from the reader—it’s all deftly plotted and very taut, and the revelation at the end about the purpose of this game which our narrator has got himself locked into turns out to be really interesting and expansive. Which is the point, I think, and the problem with escape rooms—there’s got to be a reason why you’re there in the first place.

January 8, 2019

Gleanings

- “And you realize that if we lived in a country that had its priorities straight, there would be no falling-down schools, and teachers would be paid $100,000 a year to start.”

- “But there’s strain of irrational angst, mad love, punched-in-the-gut pain, that no person, that no village, no matter how big can relieve a mother of. I realize now that pregnancy was just preparing me for it.”

- “I wore my job like a suit of armour—nothing would interrupt my ambition. I wasn’t okay, but I couldn’t admit it, let alone explain it.”

- “And so it goes, I thought, when families get together: we’re mutually astonished.”

- “10 More Things I’ve Learned Working at the Public Library.”

- “Who are the Golden Girls of Prospect Cemetery and why did they decide to spend eternity together?”

- “I always tell my daughters they can be anything they want, so long as they don’t make other people feel uncomfortable. “

- “It’s Christmas Eve, and you get to be in charge of your own magic.”

- “It was a phase and now I’m in a different one.”

- “But where does the wax go? I was awake early wondering. It must be the same place firewood goes when it burns, only part of the log reduced to ash. It goes to heat and smoke, to water, to carbon dioxide.”

- “Rather than following Kondo’s rules, I’d like to suggest another: it should be obligatory that all living spaces come with built-in bookshelves. (And a hammock.)”

January 8, 2019

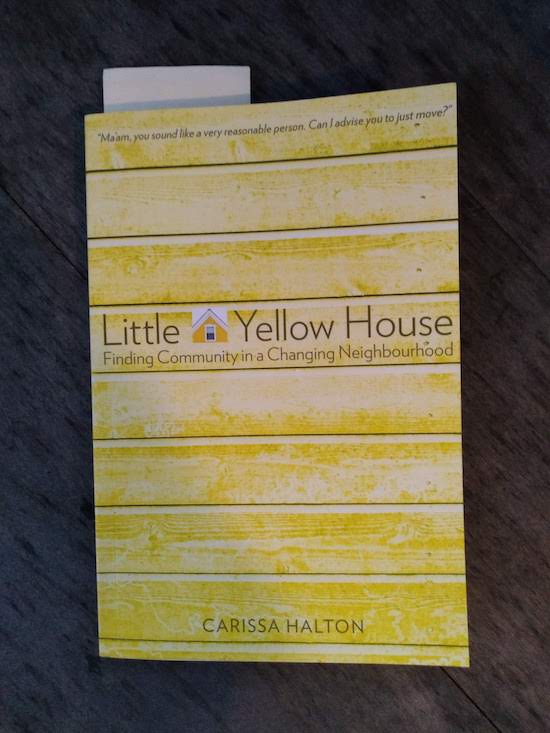

Little Yellow House, by Carissa Halton

Last summer after a terrible thing happened in my city, I wrote a post about how “My favourite thing about living in a city is being able to disabuse myself of the notion that the place where I live is not a place where ‘something like this can happen.’ To live in a city is to live in a place where anything can happen, which is actually the case with living anywhere, but in a city we know it by heart.” Which is the kind of awareness and understanding Carissa Halton celebrates in her book, Little Yellow House: Finding Community in a Changing Neighbourhood, a collection of candid essays about being part of Edmonton’s Alberta Avenue neighbourhood, an inner-city community where all kind of things happen, some awful and others beautiful.

It is important to be clear about what her book is not: an anthropological analysis of life among the lower classes, Halton and her family taking advantage of lower real estate prices, all the while taking notes on the neighbours. Because while Halton does write about the tension inherent in her story, the “irony and responsibility” (“In the worst-case scenario, my family becomes a threat. By fixing up our home and our yard, by our activism, we run the risk of increasing property values on our street, which could lead to major affordability issues in decades to come.”) she does not see herself as removed from the world she’s describing.

She begins the book by writing about moving with her husband to what had been described to her as “the shitty part of town.” The neighbourhood was closer to their jobs, would provide them a better understanding of the people they worked with running social programs, and her grandparents had grown up there. And yes, they could afford a house. “You’ll move when you have kids,” they were told, but then they had three, and they didn’t move when the children went to school either, or when the children grew, and the house seemed smaller. “And while we wished there were fewer empty storefronts along the main avenue and fewer johns trolling to buy sex, the elm trees on the boulevard shaded the streets that led to the homes of our extended family,” and there were cafes and bakeries, playgrounds, and a library. “In short,” Halton writes, “we discovered shitty is how you see it.”

She writes about, perhaps unwisely, confronting a man dumping massive quantities of broken tiles in her alley whilst being very pregnant. “Drug Houses Make Bad Neighbours” is the terrifying story of their friends who moved into the neighbourhood in 1994 and dealt with neighbours in a dodgy rental who’d threaten the when they called police, and police who’d offer advice such as, “Ma’am, you should like a very reasonable person. Can I advise you to just move?” With a journalist’s eye, she tells the life story of a man who’d end up dying of blunt force trauma not far from where she lives who was once a little boy who wanted to be an astronaut. In “Hell is Other People,” she writes about how good fences make good neighbours, and how her band of children are sometimes her neighbour’s own hell.

Her essays are about neighbour kids, the friends she found on mat leave and how they spent their days, about a friend of a friend who took in a neighbour when he was forced out of his rooming house, where he’d been sheltering feral cats. About NIMBYs, and the joys of treasure-hunting at the thrift shop, lice and bedbugs, working at a soup kitchen, about a police officer mistaking her for a sex worker while she’s waiting at the bus stop for her kids to arrive home from school. About community initiatives to deal with the sex trade on the streets where her children play, and another essay that tells the stories of women who’ve worked on those streets. About trees and birds and greenery. About going stir-crazy as a stay-at-home mom, and finding enterprising ways to make their smaller home work as their family grows.

Great cities and neighbourhoods are containers for stories, just like this book is, and every one of these is delightfully readable and well-written right down to the sentence level. And Halton is not afraid of tension, of ambiguity and uncertainty, something living in the city teaches you, and so each of these stories is suspended in a careful place, not neatly packaged or simply concluded. Which gives their culmination the effect of a walk through a city street, of glimpses, moments, and changing scenes—a most satisfying and delightful excursion.

January 3, 2019

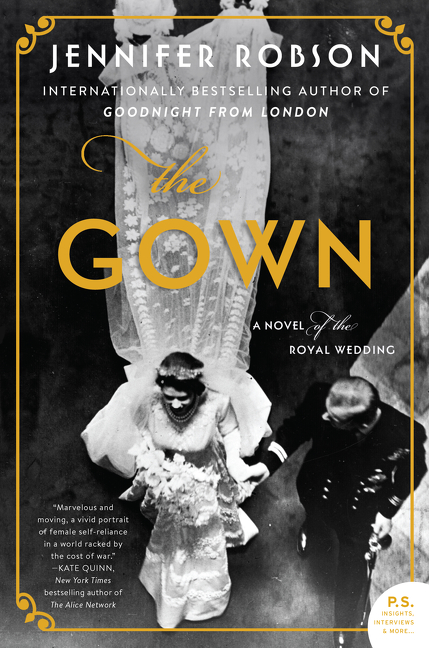

The Gown, by Jennifer Robson

Jennifer Robson is my friend, in addition to being a superstar bestselling novelist, and while her latest book, The Gown, is the first novel I’ve read in 2019, I didn’t set out with plans to write about it. I was reading it for fun, you see, and I’m still not properly off-vacation anyway, so I thought that this book, which tells the story of two women who worked on the embroidery on Princess Elizabeth’s wedding gown for her 1947 wedding to Prince Philip, would be a mostly just an enjoyable endeavour. And it was, beginning with the two narrative threads set in 1947 London (from the perspectives of a working class English woman living on her own and another who has just emigrated from France with a reference letter from Christian Dior, hoping to leave wartime trauma behind her), and another in Toronto in 2016 (a journalist is laid off from her job at a magazine and decides to pursue the mystery of a piece of embroidery found among her late grandmother’s possessions). The threads themselves perfectly nice and even lovely, and I was thinking, “I like this book. Good for Jen Robson…” And then about 100 pages in, suddenly I was unable to think about anything but the story and I only wanted to read it, and it was more like, Good for Jen Robson for being a novel-writing genius. It’s not the threads themselves, but what she does with them, how they’re woven together to create a plot that’s deeply compelling, a setting that’s oh-so evocative. A story about ladies and tea and sewing that it also a novel about class divides, date rape, the Holocaust, systemic barriers for working class women, female friendship, the utter deprivation that was England under austerity in 1947, and yes, about the royal wedding.

But it was her ideas about art that really made me want to write about The Gown, about what’s allowed to be Art and what isn’t. Unsurprisingly, she had me at the part where Ann puts down her mending and picks up a teacup painted with countryside scenes. “So I took them down to the antiques shop on Ripple Road, and the fellow there looked at the pieces and said they were Royal Worcester… He told me they were painted by a man named Harry Stinton. He said Harry Stinton was one of the best artists of the last hundred years. And you can’t tell me the paintings on this cup and saucer aren’t art, because they are.” She’s explaining this to her friend and housemate Miriam, who is beginning a project in which the story of family—murdered at Auschwitz—is memorialized on a series of embroidery panels. Miriam is an artist, Ann is insisting, even if she isn’t “carving marble sculptures or painting oil portraits of politicians.” And there is artistry too in the embroidery that went into a wedding dress for a princess, work for which the women who did it received no acknowledgement. And so the entire novel is a way to have their story told. As Robson explained in Entertainment Weekly, “If there’s one overriding reason that I write, it’s to give voices to women who lived in the past.”

It all had me thinking about what kind of writing, what kind of books, are allowed to be Art, are allowed to be Literature. How we are forever forced to endure manifestos by male critics about how literature is not enough of a national expression, or else an aesthetic pursuit, or even the one about it’s being destroyed by writers’ social connections and an abandonment of individuality (by which he means: Down with women and friendship!). How in order to be Art, a book must be appreciated at the sentence level, and any appeal above that is frivolity. I would not consider approaching any of these critics for their opinions on work rendered on fine bone china.

And I’ve always been confused about what their objectives are, what it would mean if their visions came to be pass and we all decided that indeed, a book should only ever be just one single thing. It occurs to me that this is like declaring that artistic expression must only be conveyed by oil paints and canvas, which means no more sculpture, textiles, alley murals, comic strips, photography, and patterns on teacups. Imagine no more embroidery, or beading, or lace, or quilts, or patterns in the carpets—and of course, there is a gendered element to all of this. What a somber expedition every trip to the gallery would be.

I loved The Gown for its characters, plot and setting, and fascinating historical detail—Robson has a doctorate in British economic and social history from Oxford University. But I especially loved it for shining a light on the craft, talent and vision—genius—necessary for the creation of art that is beautiful, useful, and even commercial. These are works that, instead of being rarefied, are part and parcel of everyday life, which are all the more reason to celebrate them and declare how much they matter.

January 2, 2019

Happy New Year

No one got sick on our holiday—no pneumonia, or strep throat, and even the colds were fairly unspectacular. No one threw up on Christmas Eve, which is the first time ever that such a miracle has transpired in recent memory, and could be down to the fact that we ate bread and chicken noodle soup for dinner that night, because it had occurred to me that there could possibly be a correlation between the rich foods we eat every December 24 and the inevitable puking, although it’s embarrassing that it took me so many years to figure this out. With bread and broth, however, all the stomachs were settled, and it all has been a very low-key, relaxing, restorative and pleasant holiday.

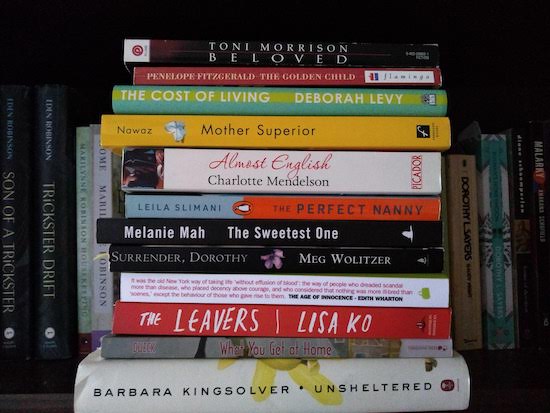

Mostly, I just read books, so many books, barrelling through titles on my To-Be-Read shelf, and also getting rid of other books that have been sitting there for years and that I’m never ever going to reading. True confession: the piles of books I had before me* have been overwhelming for quite some time, and reading should never feel that way. *These aren’t necessarily the books I’m sent by publishers, because I’m less responsible for these. Instead the ones that I’ve been picked up on my travels, and have not made enough time for. So I skipped the used book sales this fall, and made a point of reading the books I had this holiday, and now I feel much less likely to die in a book avalanche, which is an excellent way to start off the new year.

The downside to this, however, is that now I’m going to around telling everyone about this amazing novel called Beloved, by Toni Morrison, which only came out and won the Pulitzer Prize 30 years ago, so I’m really on the cutting edge, right? So hip and current. But oh my gosh, the book is extraordinary, and I can see how it ties right into the contemporary Black women writers whose work I’ve been loving these last few years. Another buzz worthy pick was The Age of Innocence, by Edith Wharton, which is not quite a new release, instead 97 years old, but I did get the spectacularly designed new edition from Gladstone Press, and it was gorgeous, and such a pleasure to read.

I also really loved Barbara Kingsolver’s Unsheltered, which I asked for for Christmas after reading this profile in The Guardian in October. It starts off kind of clumsily and didactic, more about ideas than being a novel proper, but the ideas were so interesting that I didn’t mind, and I also loved how well the two different storylines worked, that I was interested in both of them. And then partway through the book, the narrative grew legs, and I’ve been thinking about it steadily ever since I finished reading.

But I wasn’t only reading. And how can a person read this many books and not only be reading, you might ask? The answer being: I turned off my wifi for a week for my biannual holiday from the internet. It was glorious. I don’t have data on my phone anyway, so no wifi rendered me entirely internetless, and while I love the internet, since I’ve returned to it it’s only occurred to me that Twitter is wholly joyless, Facebook is pointless, and I like Instagram a lot still, but want to make our relationship more casual. And I want to focus on my blog instead, an online space that as ever is in transition. I’m going to be writing more about this in the coming weeks, about what blogs might be turning into. I’m not sure, but I think that for me, mine might be my online salvation. Stay tuned.

While I wasn’t reading, I was ice skating, checking out museums and galleries, playing card games—we got Rhino Hero for Christmas, and I love it with all my heart. I was knitting and delighting in Fargo Season 3 and watching Mary Poppins Comes Back, and going to for walks down residential streets and through ravines, and making turkey leftovers into all kinds of different things, and seeing friends, and even cousins (which I don’t have enough exposure to and which have always been my favourite part of Christmas), and also reading. Every day when I woke up, the first thing I did was turn on my bedside lamp and pick up my book, which is my very favourite way to start the day, and sometimes people even brought me tea.

And now it’s a new year, and my house is really tidy, after a marathon clear-out on Sunday (including a thorough pruning of my shelves to make space for the books I read on the holidays). I also have a new coat that doesn’t make me look like a hobo, and bought new bras, which was an errand that was three years overdue. Plus, I am currently in the midst of my ideal state of being, ie I am awaiting the arrival of a teapot in the post. What that I could be suspended in this reality forever, but when it ceases I will have the consolation of a teapot at least.

December 20, 2018

Things I Wrote in 2018

I’m sharing this list of things I wrote in 2018, inspired by the twitter meme, partly because I’m really proud of the articles and reviews I wrote this year, of the range of topics covered, of how important and necessary it is to be telling stories like these right now. I’m really grateful for the opportunity to publish work about abortion and family life, inspiring Indigenous women, school funding, and books, books, books. As ever, I am also really grateful to be able to write about books all year long at 49thShelf.com, which celebrates Canadian writers and writing. From this work I can say unequivocally that Canadian books are amazing, and its a privilege to be part of this community as a reader and a writer.

I’m sharing this list too because it’s been over a year since my novel came out, and while the year of Mitzi Bytes was full of joy as the book went into the world, there were lows along with the highs. It was a roller coaster year, and I was never sure what the following year might have in store. So really everything good that happened writing-wise in 2018 seems like it was the sweetest surprise, which is nice to know about as I move into a 2019 that has yet to reveal what it’s all going to be.

December 19, 2018

The flower can always be changing, by Shawna Lemay

“All summer long, flowers. And all winter long the path through the garden is inward. A time to learn to be awake to the flowers within. What is there to fear? I’ve come to understand the souls is a flower with which to bless the world.” —”All Summer Long Flowers”

The flowers were indeed always changing, but the book was the same, this book that came into my life in April, The Flower Can Always Be Changing, by Shawna Lemay, the week before the crocuses bloomed. and it has sat by my bedside ever since. I’ve read it twice, a little at a time, as befits a collection of brief essays. It’s not a diary exactly, but it reads like one, the essays guided by the seasons. The collection’s title inspired by Woolf’s own diary, a line she wrote as she was writing, The Waves: “A lamp and a flower pot in the centre. The flower can always be changing.”

The meaning a bit obscure to me—but when is Woolf ever not? Thinking about the way that a flower is always different as it blooms and then decays, and then turns into a different flower altogether. Lemay writes about “grocery store flowers,” although I prefer the convenience store variety, how the tulip becomes an iris becomes a gerbera becomes and dahlia, and so on.

I first met Shawna Lemay though her blog, although it was a different blog than the blog she has now, a blog called Calm Things. Which was connected to her book of the same title, essays about living with an artist, with art, about still lives. As with Woolf, always a bit obscure. The meaning can always be changing.

And blogs have informed Lemay’s work so much, this book included, a chronicle of dailiness, of routine, of interruptions to that routine. A record of noticings, of shifts in how the light falls. “Align yourself to the poetry of the everyday.”

Lemay’s blog two blogs ago was called “Capacious Hold-All” (which was a reference to how Woolf had described her diary; Lemay is also author of the purse-inspired novel Rumi and Red Handbag), and The Flower is similarly structured. Essays like posts, titles such as, “A Few Things About Working in a Library.” Others like axioms, jokes, one-liners, answers to questions, lists. She writes about experiencing Bell’s Palsy, about reading and writing, about being a writer, about what people expect of you when you’re a writer, versus who you really are. She shares lines from poetry and fiction. “Keep Your Solitude” begins, “At the end of Mrs. Dalloway, the discussion between Sally and Peter is about how it’s possible to know people.” “Civilized” starts with, “They had yet to unfriend each other on Facebook.” And indeed, these essays weave between preoccupations online and off it. For Lemay, the internet fuels her creativity, and is as much a part of her practice as the flowers.

I’ve been wanting to write about this book, because it’s strange and beautiful, and I’ve carried it with me all these months, since the flowers started blooming. But it’s been hard to do so, because as the book is slow and thoughtful, so has been my engagement with it. Even now that I’ve finished reading it a second time, I’m not about to put it up on my shelf, to put it away yet. I’m going to keep it by my bedside instead, for dipping in and out, because every time I open it, I seem to find something perfect and new.

“I want to say that what makes me beautiful is I know how to endure the deep winter and how when the snow falls it changes my soul. I want to say winter strengthens me but I know the grocery store flowers are the only reason I make it through.” —”Transcendance”