July 24, 2020

122 Days

I don’t remember my last swim, though I remember the date. March 11, which stands out for many of us in all kinds of ways, and it was the last day of a lot of things—that evening I would run my cart through the grocery store heaped with cans of beans and bags of chips (necessary supplies for impending disaster). It was the last day my children were both at school, because Iris woke up with a cough on Thursday and I didn’t want to chance it. It was the last day of normal life still seeming like a possibility, through we had cancelled our trip to England, which was due to happen the following week. But on Wednesday March 11, we still weren’t sure we weren’t overreacting. By Thursday morning, I would be overwhelmed with dread and skipping my swim (why chance it?), my towel and bathing suit hanging over the railing in my bedroom where they would stay for the next four months.

I need to have a towel hanging on the railing, even when I’m not swimming at all.

But then last week at the cottage (I think it’s interesting the way we say “at the cottage” as though there were one, as though the specificity mattered in the slightest), there were towels hanging on the railing all week. There were bath towels too, but we didn’t even use them, because nobody is required to shower when you swim in the lake every day. Every day twice a day.

We’ve never had our own personal waterfront before, been just 47 steps from a swim. Though it wasn’t so much more than that in that 100-days-ago era, back when I used to swim every morning, when I would leave the house at 7:00am and be in the pool by 7:15, pushing off for my very first length, never once taking such an extraordinary privilege for granted.

But on summer holiday, there is no such need for early rising, and it’s far more vital to linger in bed with refilled cups of tea. Finally making our way down to the water mid-morning once the heat of the day had started rising, and leaping off the end of the dock. Every day I got to fly.

Truth be told, I’ve been able to fill the swimming void. We do yoga every morning and it makes my body feel the same way swimming does, stretched and limber. For exercise, I’ve been riding a stationary bicycle, which I don’t like—but at least it permits me to read at the same time. It turns out that as much as swimming itself, I missed the aesthetics of swimming. I saw an illustration of a blue circle back in the spring, and it moved me to tears. We bought a smallish pool for our backyard, and while I can’t swim in it, I can sit on an inflatable tube and float, which fulfills nearly all my aquatic needs.

But there is something about a lake, particularly one that’s 47 steps down from the door. A lake on such rugged terrain that there is no seaweed, but instead rock-faces, rocks themselves, and long lost tree trunks. The water so clear that I could see down to the bottom: a kitchen sink, a sunken rowboat.

Every day, I swam across our bay to the beach on the other side, equipped with goggles and earplugs. Last summer I could swim long distance, all the way to the island where we picnic, but now I’m out of practice. There was a point where our inflatable flamingo was taken by the wind, and I chased after it, caught it, so I’ve still got it, is what I’m saying. Not much of it, mind, but it was the most exhilarating swim of the holiday for sure.

I’d wondered about renting a cottage without a beach—it was a “con” as we were choosing a place. But it turned out to be the best thing ever—no sand, not a grain of it, which under normal cottage week situations would be caught up in my bed sheets by Tuesday, and I’d be sweeping the floor at least five times a day. Okay, we were still sweeping the floor, because whoever owned the place appears to have had a very, very fluffy white dog… But the lack of sand was amazing. Who needs sand anyway? Beaches are nothing compared with the end of a dock, the leap and the plunge. The kids who get to show off their swimming skills, nervous as the holiday began, but by the end of the week, they were fish.

We had one last swim before we left on Saturday. (I have completely forgotten about the horseflies, as I knew I would. You can’t see them in the photographs.) Like all the other swims, this one was perfect. Smallish lakes are always the nicest temperature in July, invigorating but inviting. When we got home that afternoon, the towels were still damp, like a memory.

September 11, 2018

I am a swimmer

What I have to show for my last decade in athletics is not a whole lot—I once signed up for ten yoga classes but only went to one, and we still have the evidence of the running shoes my husband bought me when I decided to take up jogging that show remarkably little wear. Which is just two examples, and narratively anti-climactic, but it underlines the point I’m trying to make: I dislike most forms of exercise so much that I rarely quit them, because I’d have to join them first. Not doing things I dislike doing is pretty much the cornerstone of my approach to being alive: I don’t want to push through the pain, or feel the burn. If being miserable, even for limited periods of time, is a pre-requisite for physical activity, than take my name off the list. For a while I made do with a stationary bicycle, because while riding it at least I could read.

But now—like the shoes, and like the yoga passes nearly a decade expired, the stationary bicycle sits unused—draped with winter coats in an upstairs closet. It’s been at least two years since I’ve sat upon its little seat and spun its futile wheels into nowhere—but not for the reason you might be thinking. Oh, no. Because it’s also been two years now since I purchased a membership to the university athletic centre near my house. A membership I bought (inspired by Lindsay) just after getting a raise at my job and therefore being able to afford to put my youngest daughter in full-day preschool, which left time in the day for some kind of physical activity. I would go swimming, I decided. Maybe this would be a thing I could do, and I wouldn’t quit, because it wouldn’t be awful.

And it wasn’t, and I didn’t. And in the next few days, I will renew my membership again. Because I love it, swimming. I love it so much, I get up early in the morning to do it, much to the surprise of the people who know me, because it’s the only thing I’ve ever gotten out of bed for, and before 7am either. Four days a week (but not Friday, because on Friday everyone at rec swim is crammed into half of the 50 metre pool—the long half and not the short half—and it’s crowded and unpleasant) I wake up at 6:50 am and wriggle into my bathing suit, which is set out with my towel. Throw on clothes over top and rush to the pool, where I’m in the water by 7:15, and I swim for half an hour. During which I think, catalogue anxieties, solve plot problems, compose blog posts, try to remember all the verses to “American Pie,” and swim back and forth in the medium lane. Which is so my speed—the medium lane. It’s where I like to be.

I’ve loved swimming for a long time—I was lucky to have a pool in my backyard when I was growing up, and so even though I failed Bronze Cross twice because I couldn’t do the timed swim, I recall spending ages under water, turning somersaults, leaping high, partaking in an agility I did not partake in on dry land. When I lived in England, I longed for lakes, and once went swimming in a pond just to get my fix. One day on holiday in 2004, Stuart and I jumped into a hotel pool and discovered after two years together that we both liked swimming a lot, so much so that later in the week we’d jump into another hotel pool even though it was green, and I’d get a rash—me getting a rash will become a running theme here. And when I was pregnant with Harriet, I worked at the university, and went swimming every day on my lunch hour, delighting in the freedom of movement, and of floating suspended the way my baby was—the very first thing we ever did together.

But it’s hard to fit swimming into a busy life. For a long time, swimming was a special occasion, and I started buying expensive mail-order movie star bathing costumes to better suit my weird-postpartum body. But the thing that no one tells you about movie star bathing suits is that when you wear them a lot in chlorine, they become worn out and hideous. Six years later, my body even weirder and more-postpartum, I buy unflattering sporty suits from the clearance rack, because I like the uniform, its utilitarian nature. I am not a bathing beauty, I am a swimmer. I am a swimmer. In Swell: A Waterbiograpy, Jenny Landreth writes about the power of this realization, her reluctance to own it, how we undermine our abilities—”I’m not that good. And I’m not fast.” To belong in a space like a pool, a gym. I have a place here. It has been two years, and I am a swimmer.

I am allergic to lake water, and have a sunlight sensitivity that a lot of other people have tried to tell me that they have experienced too, and some of them have, but not the ones who say, “It’s like a heat rash, right?” Because those people have never had their eyelids swell up or been unable to sleep for unbearable itching. This year was the third summer in a row that I’ve gone through in big hats and SPF clothing, including a purple hoodie I wear in the water. (The photo above is me like a normal person in a bathing suit just because I wanted a photo opportunity. Naturally, after three minutes of sun exposure, I got a rash, but the photo was worth it.) And so it’s a bit absurd that I love swimming and beaches more than I ever did, when a practical person might find a different kind of pursuit—badminton? But we make it work. We have a sun tent so I can beach all day and stay in the shade, and when I go to the beach I always bring a bathing suit to change into, because my lake water allergy kicks in when I sit around in wet bathing suits. (I know, I know. I am infinitely sexy.) And while this is inconvenient, the result is that I now have so many bathing suits. While we were away on holiday by a lake in the summer, I marvelled at the array of them drying on pegs in our cottage bathroom—I have so many bathing suits. Because I’m allergic to lake water, okay, but also because I am a swimmer. I am a swimmer.

And I love that, having so many bathing suits. Some of which look really good on me and others (see the purple one above: NOT FLATTERING) do not, but how I look is not even the point (although it certainly is in this stunning photo to the left), but what I can do: swimsuits are for swimming. I am a swimmer. And once upon a time I paid a lot of money for a bathing suit that made me feel good, and I know there are other women for whom bathing suit shopping is a form of torture, and some women who won’t appear in public in a bathing suit at all. Whereas I have a bathing suit bouquet. And as a woman on the cusp of being forty, I see this as an accomplishment I’m proud of, how it sets the kind of example I want to set for the two small women I gave birth to. An indication that I’m right where I want to be at this point in my life, a good and fortunate place.

And I love that, having so many bathing suits. Some of which look really good on me and others (see the purple one above: NOT FLATTERING) do not, but how I look is not even the point (although it certainly is in this stunning photo to the left), but what I can do: swimsuits are for swimming. I am a swimmer. And once upon a time I paid a lot of money for a bathing suit that made me feel good, and I know there are other women for whom bathing suit shopping is a form of torture, and some women who won’t appear in public in a bathing suit at all. Whereas I have a bathing suit bouquet. And as a woman on the cusp of being forty, I see this as an accomplishment I’m proud of, how it sets the kind of example I want to set for the two small women I gave birth to. An indication that I’m right where I want to be at this point in my life, a good and fortunate place.

A place which is, often, literally flying.

August 15, 2018

Swell: A Waterbiography, by Jenny Landreth

The gendered nature of swimming is something I think about all the time, although most often when I am sharing a lane with a man who has found taking up ample space by merely having longer limbs than I do unacceptable, and therefore has decided to enhance his lengths with flippers on his feet and paddles on his hands, increasing his chances of making violent contact with my body as he passes me. The women in the pool I swim at don’t do this, and neither do they, as one swimmer in Jenny Landreth’s spectacular book Swell: A Waterbiography does, butterfly up and down narrow lanes driving all other swimmers into the gutter. In her recent book, Boys, Rachel Giese writes about the way that boys are taught to be entitled to public space, as they dominate the basketball courts on the playground, and because I spend most of my time hiding in libraries, I don’t encounter this very much, but it’s in the pool I do. And it all makes me think of the line on the very first page of Swell, which was where I fell in love with this book: “how swimming can be a barometer for women’s equality.” We’ve all come a long way, but still.

Swell is my favourite book I’ve read this summer, a summer that has been all about swimming, in pools and lakes, as both my children are both at pivotal stages in the development of their inner fishes, and we can worry slightly less about the little one drowning. I’ve gone swimming by myself four mornings a week along with the men with the hand paddles and the flippers, and then later in the day we’ve all gone to the public pool and I’ve sat in the shallows and tried not to think about pee as my daughters delighted in turning somersaults over and over again. So yes, Swell was just absolutely perfect.

It’s a book I’d situate as what might happen if Sue Townsend of Adrian Mole fame got together with Elizabeth Renzetti’s Shewed and they decided to have a literary baby that was also a social history of women swimming in England. The result is absolutely delightful, empowering, and so terrible funny in its asides that I kept reading them aloud to the people around me who became very confused about what this book was about exactly. But that’s because it’s about everything, about the history of suffrage, and bathing suits, and public pools, and mixed beaches, and how women used to drown all the time because they weren’t taught to swim, and about how when they decided they did want to learn how to swim, no one could teach them because all the instructors were men and men and women couldn’t possible swim together. It’s about pools where women were accorded very little time for swimming, and it was usually during the day when no one could make it anyway. It’s about women who defied convention (and their mothers!) to become swimming superstars, pioneering the front crawl in England, swimming the English channel, being the first women swimmers in the Olympic games.

Landreth writes, “‘In front of every great woman is another great woman… Women whose lies will change. Some who will take this story, make it their story and push it on to its next pages.”

And of course, Landreth’s own story is part of this book, her “waterbiography”—and she admits to being proud to have coined the term. She grew up in the Midlands, which is kind of a swimming desert—when I lived there I was once so desperate for a swim that I dove in the duck pond on the Nottingham University Jubilee Campus—and was an unlikely candidate to become an avid swimmer for a host of reasons. She writes about learning to swim as a child, about travelling to Greece in her 20s and trying proper swimming for the first time, about lacklustre swimming as part of the 1980s’ fitness craze, about what an awful and unfulfilling thing it is to go swimming with small children—and then about finding her identity as a swimmer once her children were older, and what a thing it is that women can do this at any age. About how empowering it was to learn to call herself a swimmer.

There is indeed something womanly about swimming, in spite of the Michael Phelpses and the men with paddles on their hands. I mean, have you ever heard of a male mermaid? No. And I can’t for the life of me think of a single man who’s swam across Lake Ontario, but I know about Marilyn Bell and Vicki Keith, and Annaleise Carr, a swimming hero for every generation. I have dreams of one day swimming in the Ladies Pond at Hampstead Heath. I used to buy terrifically fancy swimsuits, but lately I’ve become enamoured of my sporty suits, the ones I wear while swimming in the pool in the mornings. Where my favourite swimmer is this woman I’ve never spoken to, but she’s my hero—grey bathing cap (I wouldn’t know her without it) and same bathing suit as mine, a bit stocky, older than I am. And in the pool every morning, she’s the fastest every time.

More on swimming:

- Swimming Holes We Have Known Blog

- Katrina Onstad on public swimming pools

- Nathalie Atkinson’s article in Zoomer Magazine on swimming books (which is where I heard about Swell).

- “Drowning at Midlife? Start Swimming” from the New York Times.

- “Swimming pools are a balm for whatever ails me”

- And a swimming quilt!

December 1, 2016

Swimming Lessons: Addendum

Full disclosure necessitates I update you on how things have proceeded since I read about exiting Guardian Swim and the beginning of my new career reading on the poolside. I thought I was being so clever this time, not keeping my child in Guardian Swim until she was five, which was what happened last time. Never again was I going to have my school-age child in the same swimming class as an infant, and so Iris was enrolled in Sea Turtle. This time we were going to do it right, and it was so right, for the first two lessons, at least. Iris is part mermaid and was happily floating on her back, and she had the most excellent swimming instructor in the entire history of our life in recreational programs…and then, for absolutely no reason, when we arrived at class for Week 3, Iris refused to get into the pool. And there we’ve been ever since, Iris screaming whenever forced to come into contact with the water, turning her body into a plank or a noodle, whichever would prove most inconvenient. And when you’re a parent who’s been expecting to spent 30 minutes reading poolside, the prospect of a screaming kid refusing to enter the pool is most frustrating. There was swearing.

Full disclosure necessitates I update you on how things have proceeded since I read about exiting Guardian Swim and the beginning of my new career reading on the poolside. I thought I was being so clever this time, not keeping my child in Guardian Swim until she was five, which was what happened last time. Never again was I going to have my school-age child in the same swimming class as an infant, and so Iris was enrolled in Sea Turtle. This time we were going to do it right, and it was so right, for the first two lessons, at least. Iris is part mermaid and was happily floating on her back, and she had the most excellent swimming instructor in the entire history of our life in recreational programs…and then, for absolutely no reason, when we arrived at class for Week 3, Iris refused to get into the pool. And there we’ve been ever since, Iris screaming whenever forced to come into contact with the water, turning her body into a plank or a noodle, whichever would prove most inconvenient. And when you’re a parent who’s been expecting to spent 30 minutes reading poolside, the prospect of a screaming kid refusing to enter the pool is most frustrating. There was swearing.

Last week was the second last class, and there was finally progress. Iris got in the pool, but in order for this to happen I had to be crouching at the pool’s edge, basically sitting in a puddle and being splashed whenever anyone practiced kicking. There was no reading.

All of which is to say that this underlines my growing suspicion that there is really no way to do parenthood right. No matter how you swing things, they’re probably always going to be a bit annoying.

October 4, 2016

Goodbye, Guardian Swim.

When Harriet was a baby, we had no money but plenty of time, and so instead of enrolling her in swimming lessons as the swishy pool near our house (with salt water and everything!) I signed up for cheap swimming lessons at the city-run pool that was far away and at the top of the only hill in this entire city. It was better than joining a gym, I decided, and only cost $33 dollars, and so began my Guardian Swim years, which is the more inclusive name for the Parent and Tot program I remember from my own childhood.

When Harriet was a baby, we had no money but plenty of time, and so instead of enrolling her in swimming lessons as the swishy pool near our house (with salt water and everything!) I signed up for cheap swimming lessons at the city-run pool that was far away and at the top of the only hill in this entire city. It was better than joining a gym, I decided, and only cost $33 dollars, and so began my Guardian Swim years, which is the more inclusive name for the Parent and Tot program I remember from my own childhood.

In the beginning, I was very excited. In the beginning, I find, parents need to strive in order to enact parenthood properly (luckily, many of us outgrow this compulsion) and guardian swim was one way to do so. It was also something to do with my baby that didn’t involve me lying on the carpet being bored out of my mind. It got us out of the house. (The idea that there was a time in my life when I was desperate for excuses to “get out of the house” distresses me now. That sounds awful. I never want to be that person ever ever again.) I am sure I found the first lesson exhilarating. Fortunately, I was never that poor parent whose baby screamed throughout the entire lesson every week and eventually we had to give up going swimming altogether, $33 dollars sadly to waste. Harriet liked the water, I liked having something to do, and so we did it, session after session. I have done “The Fish Wishy” so many times.

Oh, Guardian Swim. Once in a while I signed up for you, and the first class would have this terrific, dynamic teacher with lots of games, songs and ideas, and every time we met that teacher, she or he taught the one class and we never saw them again. Most of the other instructors had a short repertoire, and then would grant the class “free time,” and my baby and I would flounder aimlessly in the pool watching the clock until it was time to go home. There would be plastic toys, and the children would be drawn to them, but once the baby had a toy boat in hand, there wouldn’t be so much to do.

My most favourite part of Guardian Swim was when my husband took the baby into the pool, and I sat poolside reading a book. My least favourite part was when the instructor would give us an obligatory educational session, like how we shouldn’t leave our babies unattended by backyard pools or feed them marbles in case they choked. I also wasn’t big into the times that people pointed out that swim diapers contain faces but not urine, the thing that most of were trying really hard not to think about. There was the sessions with Shaheed, who was the worst teacher ever, and often would forget to come class, never mind that I’d climbed that hill and got my kid ready for it (and got out of the house even—no small feat) and when we got there and he wasn’t, they wouldn’t let us get in the pool. The seventeen-year-old lifeguard would shrug, no idea about my sacrifice—”Nothing I can do,” he’d say.

From Guardian Swim, I learned that I should get dressed before my child does, otherwise she will take her dry-clothed-self and sit right down in a puddle on the change room floor. I learned that she could play with my keys while I got changed, and be sufficiently entertained. She learned how to blow bubbles and how to kick her little legs. I learned not to feed her marbles. Nobody, however, ever learned to swim.

When Harriet was nearly four, she was still in Guardian Swim. I look back upon this with the confusion many parents do when they consider their experiences with their first child. Why were we still doing that? I think part of the problem was that she was terrified of us letting go of her in the water, and clung to me so hard it strangled. She wasn’t comfortable, and neither was I. I was waiting for something to happen, something to happen that would allow us to progress, but that something never arrived. The last time I signed Harriet up for Guardian Swim at the pool at the top of that great big hill, I was very pregnant, and I’d never considered the agony of pushing a stroller with a four-year-old up at that hill in such a condition. It was terrible. Harriet wasn’t learning anything, and there was a six-month-old baby in her class who had better technique than she had. Something was going to have to change.

When Iris was born, we were no longer broke. Not only could we afford the salt-water pool, but the convenience seemed worth every penny. Harriet began a swim program that wasn’t geared to infants, and it was Iris’s turn for Guardian Swim. Which I think she was enrolled in three times total. Because neither of us felt like getting in the pool, and it was always cold, and she always had a cold. I was tired of doing the fishy wishy.

When Iris was born, we were no longer broke. Not only could we afford the salt-water pool, but the convenience seemed worth every penny. Harriet began a swim program that wasn’t geared to infants, and it was Iris’s turn for Guardian Swim. Which I think she was enrolled in three times total. Because neither of us felt like getting in the pool, and it was always cold, and she always had a cold. I was tired of doing the fishy wishy.

We moved to the nearby university pool eventually (spoiled for pool choice, I know) because Harriet needed some help getting caught up and the shallow teaching pool gave her more confidence. The half hours we passed in that pool during Iris’s classes could possibly be scientifically proven to be the longest 30 minutes on record. Even though Iris could actually swim. Like, she was leaping out of our arms and we kept having to catch her before she sunk, and if we’d been daring enough not to bother, she might have floated after all.

By this point, we hated Guardian Swim. It was unfathomably boring. The other children were annoying. The teachers were children. Every week we’d go, and I’d cross my fingers for a pool fouling so we could go home early.

But finally, we have arrived. Last week Harriet began her first swim lesson in the “big pool” upstairs, and she was the first kid in her class to jump in the water (when once upon a time, she was vehemently opposed to such things, and I used to berate her about it, made her practice jumping off the bottom step of our staircase until she cried—not my finest moment as a parent, and it turns out her instructor was right when he suggested we leave her alone and she’d figure it out in time). And Iris started Sea Turtle, the first level post-Guardian Swim, and she was amazing, dunking her head and floating on her back, and these things that she would never have been brave enough to do had I been in the pool alongside her.

And me? I was where I’d always been waiting to be, cheering along poolside, content in the company of an excellent book. So happy with the progress, which is generally where I tend to be in terms of parenting, not looking back in sadness but just so happy to be moving on. Enjoying the ride. “Little girls get a little less little but instead of it feeling sad, it feels exhilarating,” writes Rebecca Woolf on the occasion of her daughter’s eighth birthday, and I love that idea.

Why not embrace the momentum, because it’s not going anywhere—but you are.

September 19, 2016

Swimming

Emboldened by the fact of my children being enrolled in school between the hours of 9 and 3, and inspired by blog Swimming Holes We Have Known (which had me craving blue waters all summer long), I joined the university swimming pool last week, which is conveniently located minutes from my house and the playschool. For a half hour every day, I’ve been swimming lengths in the medium-slow lane, usually just after writing my daily 1000 words of my novel (which hit 71,000 words last week) and so I’m usually mediating on problems of character as I swim (and also pondering what Mad Men has taught me about storytelling). The last time I swam regularly was when I was pregnant with Harriet, which I wrote about here, and so the whole experience in terms of senses and psyche is tied up with the feelings of physical well-being I felt during that time, and also something womb-like, which is not original or such a stretch, but still. It’s the only kind of exercise that I don’t hate—that I love, even (though we’re only one week in, but still there’s something to this).

April 30, 2015

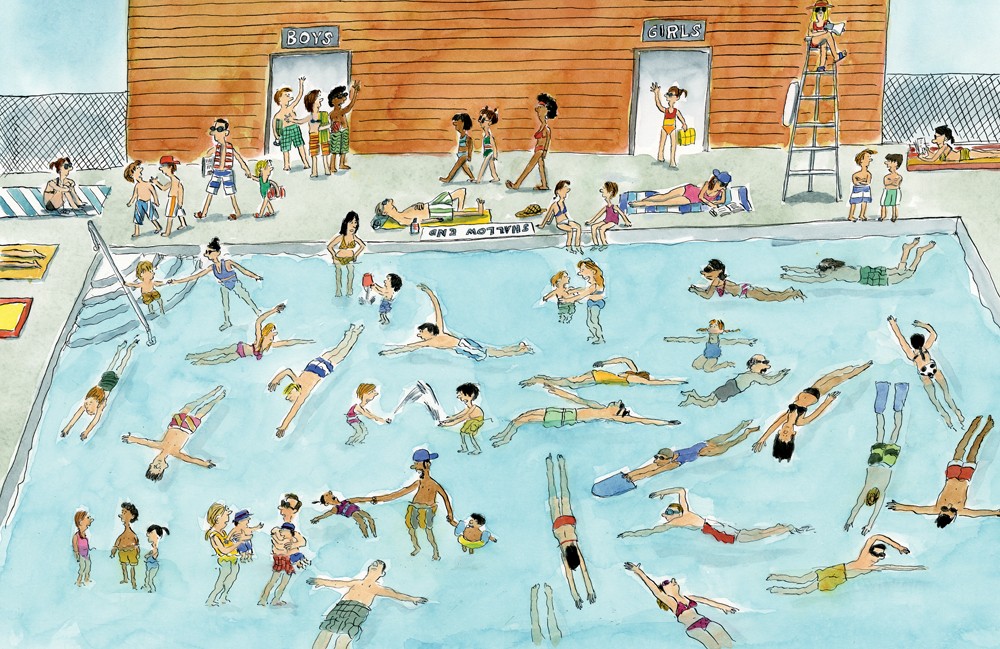

Swimming Swimming by Gary Clement

I love so many things about Gary Clement’s picture book, Swimming, Swimming, whose text is the lyrics to the traditional song that begins, “Swimming, swimming, in the swimming pool…” First, that it’s a book to be sung to, which is often engaging to readers who might not be engaged by being read to or partial to sitting still. It’s a song that’s fun to sing, even more fun to howl. Second, that it’s a summer-in-the-city book, celebrating the goodness of the public pool, an institution as vital as the library (which is saying something). In our family, we’ve become fond of swimming in the summer at the pool at Christie Pits, which is always crowded and attracts a more diverse crowd than anywhere else we ever go. There’s never any room to actually swim, I’m always irritated by teenage boys plunging in and splashing my children, and probably everyone is peeing, but friction, close quarters and pee are an inevitable part of urban life. There is beauty in the chaos, in the unabashed humanness of it all, and on hot summer days, there is no sweeter relief.

In fun, vintage style cartoon drawings (a style he used to similar effect in the nostalgia-driven Oy, Feh, So?, written by Cary Fagan), Clement depicts a summer day in the life of a swim-obsessed boy—obsession demonstrated by posters on the his walls, a diving trophy on his bureau, the fish in the bowl. And I love too this portrayal of a young person’s singular passion. The boy’s pals come by to pick him up, and together they make their way to the pool, practising their strokes along the sidewalk in a funky choreography.

They get changed, shower, arrive on deck—which is crowded with people of all ages, sizes and colours—and the song begins. It begins with the boy and his friends (the text in voice bubbles), but those around them join in the for the next line. The characters play off each other, acting out their signature strokes (and do like “fancy diving too!” in big rainbow letters, the illustration a vertical spread, as the girl of the group of friends leaps from the diving board in a loop-de-loop). And by the end of the song, everyone in the pool has stopped to face the reader and deliver the song’s final line, a very worthy question: “Oh don’t you wish you never had anything else to do?”

But alas, the pool is closing. (Or has their been a fouling?) Everybody packs up their towels and sunscreen, and makes their way for the locker room, a mirror image of the first half of the book augmented by a quick trip to the nearby ice cream truck (and this is summer-in-the-city indeed). The boy heads home, eats his dinner, feeds the fish, and collapses into bed, the goggles he’s still holding in his hand as he sleeps suggesting that tomorrow might be a day just like today was.

March 31, 2015

The Big Swim by Carrie Saxifrage

Books come from trees, and I’ve got this theory they never entirely shake their wild origins. I think this every time I’m reading outside in the spring and blossoms rain down on my book’s pages, or when a tiny midge appears and sits down at the end of a sentence. The poetry book Decomp by Stephen Collis and Jordan Scott was created from what remained of copies of Origin of Species that had been left in five distinct ecosystems to decay for a year, and I love that idea: of books and reading being so firmly embedded in nature, like they belong there. And in her extraordinary book of essays, The Big Swim, Carrie Saxifrage underlines this point, with references to literary pumpkins (Linus’s, Cinderella’s, and Peter Pumpkin Eater’s wife’s) in her essay on growing a 300 lb. squash; by recounting her grand awakening to the perils of climate change that came with reading—a series of articles by Elizabeth Kolbert; by explaining that she writes about climate change because it’s the one thing that relieves her heartbreak about understanding what we’re doing to our planet; and finally by making the natural world come alive for her reader, capturing the wonderfulness and wondrousness of nature in sparking, evocative prose.

Books come from trees, and I’ve got this theory they never entirely shake their wild origins. I think this every time I’m reading outside in the spring and blossoms rain down on my book’s pages, or when a tiny midge appears and sits down at the end of a sentence. The poetry book Decomp by Stephen Collis and Jordan Scott was created from what remained of copies of Origin of Species that had been left in five distinct ecosystems to decay for a year, and I love that idea: of books and reading being so firmly embedded in nature, like they belong there. And in her extraordinary book of essays, The Big Swim, Carrie Saxifrage underlines this point, with references to literary pumpkins (Linus’s, Cinderella’s, and Peter Pumpkin Eater’s wife’s) in her essay on growing a 300 lb. squash; by recounting her grand awakening to the perils of climate change that came with reading—a series of articles by Elizabeth Kolbert; by explaining that she writes about climate change because it’s the one thing that relieves her heartbreak about understanding what we’re doing to our planet; and finally by making the natural world come alive for her reader, capturing the wonderfulness and wondrousness of nature in sparking, evocative prose.

The next best thing to a tree for a tree to be, I’d say, would be any single page in this extraordinary book.

Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring meets Annie Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek meets Elizabeth Gilbert’s Eat Pray Love, with a healthy dose of Barbara Kingsolver—perhaps Animal Vegetable Miracle, a book that woke me up to the wonders of eating by the season, local food movements, and that potato have greens—who knew? In 12 absorbing, funny, and thoughtful essays, Carrie Saxifrage connects the personal with the universal and the scientific to the spiritual to celebrate her love for the world and confront her anxiety about its fate.

It’s a perfect book for spring, I think. Partly because bunnies turn up twice. The first time in “Hare,” when Saxifrage writes about tensions between “tree-huggers and rednecks” on her home of Cortes Island, BC. A friend whose family has ties to the local logging industry dares to bridge the gap between the two groups, but it all gets very complicated. (There is a blockade at one point, and Saxifrage offers muffins to everyone on sides, and I do so like that she appreciates the value of the muffin as a political tool.) A long story and good intentions lead to Saxifrage dressing up as “The Easter Hare” (not the bunny, no, this is the pagan symbol for springtime fertility) for the Volunteer Firefighter’s Easter Brunch, but things go wrong as best intentions always do, and our heroine ends up locked in a bathroom with terrifying children threatening to break down the door. In the end, Saxifrage resolves to get on side with her friend’s family by “non-controversial public service” in the future. Hopefully there still can be muffins.

In “Lagomorphic Resonance,” Saxifrage is hiking alone in Washington State, the same places she’d visited years before with a friend who’d later died: “It still felt like some remnant of Paul and me, as we had been, remained in the place itself.” And she’s there to see the pikas, mouselike creatures who are cousins of rabbits and live high up on mountains, who “seem like one of the many improbable details of the world’s enormous diversity.” The essay is partly about rumours of the pika’s endangerment, threats to its habitat by rising temperatures due to climate change, partly about her anxiety as mother of a teenager (and this anxiety hangs over a lot of the text in a really interesting way), about loss and memory, and the tremendous glory of being alone in quiet places.

The essays aren’t so much about what they’re about as they’re about narrative, and so many facts, anecdotes, sidelines adding layers of meaning to the reading experience. In the title essay, Saxifrage swims five miles in the cold ocean between Cortes Island and Quadra Island, capturing the unsexy details of such an endeavour (her entire body covered in lanolin to protect against the cold) and the thrilling ones, about the pleasures of swimming and its movements, of immersion, the challenges of endurance. It’s one of the best bits of swim-lit I’ve ever read: “Romantically speaking, I’m part ocean mammal. I spend time thinking about how real mermaids would actually swim… I’m strongly related to the marine branch of the family tree.” And why does she she partake in the splendid agony of these five mile swims? Because they permit her to “belong…to a vast, cold world where brilliant seaweed banners wave in exultation.”

(So yes, my love of this book also isn’t just because of what the essays are about, but because of how the writing is so incredibly good.)

In “Pumpkin People,” Saxifrage attempts to make her way into the community on Cortes Island where she has arrived as a homesteader (and one who was previously an American lawyer, no less…) by participating in the annual ritual of growing outsized gourds; in “Hail Mary, Shining Sea” she is awakened to the reality of climate change and its threats to the planet, this idea mingling with notions of “goodness”; pursuing a low-carbon lifestyle, she and her husband eventually stop flying, and so it’s by Greyhound bus that she makes her way to Mexico for adventure and Spanish lessons and to be part of a shining sea in a metaphoric way. “Deep Blueberry Gestalt” is Saxifrage hiking through Vancouver’s Strathcona Park alone while reading Arne Naess’s ideas about “possibilism”: “that we must decisively come up with our view of life and find meaning in it, yet remember that more things are possible than we can imagine.”

In “The Oolichan and the Snake,” she attempts to understand First Nations opposition to the proposed Northern Gateway Pipeline by taking the Greyhound for 20 hours to Kitimat in Northern BC to listen to First Nation testimony. “A lot of people don’t understand how industrious our people really were,” explains Gerald Amos, an elder of the Haisla Nation. “On this river alone, we estimate that our people harvested 600 tonnes of oolichan in the springtime. This went on for untold generations. We’ve made our living here for thousands and thousands of years without destroying it.”

“Nectar” is a beautiful story of Saxifrage’s mother’s final days, and contains one of the loveliest lines I’ve ever read: “Maybe when you love someone…you are preparing for a moment you don’t even realize will come.” “Falling into Place” is about a confluence of her mother’s death with the discovery of an ancient human jawbone on their property. “Journey to Numen Land” I loved because Saxifrage decides that sleeping a lot is radical, and she attempts to draw connections between her sleeping and waking life to fascinating ends. She returns to the water in “River Creatures,” rafting through the Grand Canyon and swimming (of course!) part way, making connections between her mother, the fossilized creatures in the canyon walls and river guides who’d gone before her: “None of them got to preserve for all time what they loved, or even completely determine their own course. Like me, they had the opportunity to study the rapids, choose their path, and find joy in the river’s firm embrace.”

February 10, 2013

Flip Turn by Paula Eisenstein

Flip Turn, the debut novel by Paula Eisenstein, is a wonderful companion to Leanne Shapton’s memoir Swimming Studies, using fiction to address many of the questions Shapton posed in her book. What does it it mean to be defined in one’s youth by a competitive sport? How can you be yourself without the sport? Does having natural talent hinder one from trying anything that doesn’t come easy? And where does the discipline of competitive athletics come from? Where does it go when the sport is gone? Eisenstein too delves into the peculiar culture of competitive swimming, the smell of chlorine, greeny blond hair, how you should not in fact stow your wet suit in a plastic bag after morning practice but rather roll it in your towel, otherwise it will still be wet for practice later in the later and therefore impossible to put on.

Flip Turn, the debut novel by Paula Eisenstein, is a wonderful companion to Leanne Shapton’s memoir Swimming Studies, using fiction to address many of the questions Shapton posed in her book. What does it it mean to be defined in one’s youth by a competitive sport? How can you be yourself without the sport? Does having natural talent hinder one from trying anything that doesn’t come easy? And where does the discipline of competitive athletics come from? Where does it go when the sport is gone? Eisenstein too delves into the peculiar culture of competitive swimming, the smell of chlorine, greeny blond hair, how you should not in fact stow your wet suit in a plastic bag after morning practice but rather roll it in your towel, otherwise it will still be wet for practice later in the later and therefore impossible to put on.

For Eisenstein’s unnamed narrator, competitive swimming offers welcome escape from a horrifying incident in her family’s past. Her older brother had been convicted of murdering a young girl at the local YMCA in their hometown of London ON, and the family cannot help being defined by that event both among themselves and in the wider community. The protagonist of Flip Turn views her swimming successes as a chance to tell a different story about their family life, to change the narrative. If she is good, then her family is good, she figures, which is a heavy burden for a young girl to carry on her shoulders no matter how muscular those shoulders are.

In the pool is the one place where she belongs, where both her mind and her body know exactly what she needs to do in order to be successful. Whereas, at school and even among her teammates, she’s not comfortable in her skin, always feeling like an outsider, partly due to her brother’s infamy or at least her consciousness of it, and also due to the fact that to be teenaged is always to feel like something of a misfit. Home is no better–she is all too aware of the fractures in her family, tip-toeing around her parents in order to be everything her brother wasn’t. Though she has to be careful not to be too successful in her sport–every time her name appears in the local newspaper, she knows that with her surname she only serves as a reminder of the terrible thing her brother had done years before.

Eisenstein’s narrative is told in fragments, which is disconcerting at first but the reader becomes accustomed to the style. This fragmented approach makes sense as well because this character’s world is one that is very much broken, and also because any young person is only figuring out how to understand a world in pieces anyway. Flip Turn has no obvious narrative arc–the trajectory is less of an arc than lengths back and forth across a pool–except that as the story progresses, the narrator’s voice and focus changes, deepens, demonstrating that this character is indeed maturing and that her awareness of the world around her is broadening.

This broadened awareness, however, fails to lead our character to any tidy resolution and, if anything, actually makes her experiences more complicated. Which is pretty much how life works, but it also means that this novel’s abrupt ending isn’t going to satisfy everyone. Though I imagine that anyone who gets into Flip Turn isn’t going to approach its ending expecting anything vaguely book-shaped anyway. What we get here is a portrayal of consciousness instead, a singular voice infused with such tenacity that the reader is left suspecting (or perhaps just hoping?) that this is a character who someday really is going to be okay.

August 28, 2012

Swimming Studies by Leanne Shapton

It occurs to me that I could write a swimming memoir too. I was never, ever a competitive swimmer, but my life has been punctuated by pools, shores and bathing suits. There was the pool in Bangkok in 2004, with my husband, who was my boyfriend, when we were marooned in the city after missing a flight and we went swimming together for the first time in our two years together and discovered a whole new level on which we connected, that we both adored the water. There were the turquoise rectangles and kidneys that dotted the backyards of my childhood suburban landscape, the yards you’d calculate to be invited into on the very hottest days.

It occurs to me that I could write a swimming memoir too. I was never, ever a competitive swimmer, but my life has been punctuated by pools, shores and bathing suits. There was the pool in Bangkok in 2004, with my husband, who was my boyfriend, when we were marooned in the city after missing a flight and we went swimming together for the first time in our two years together and discovered a whole new level on which we connected, that we both adored the water. There were the turquoise rectangles and kidneys that dotted the backyards of my childhood suburban landscape, the yards you’d calculate to be invited into on the very hottest days.

I learned to swim at Iroquois Park in Whitby Ontario, and then at the Allan Marshall Pool at Trent University after my family moved to Peterborough. I met my best friend at the Trent pool, at swimming lessons when we were both 13, and seven years later we’d be swimming together at a reservoir when someone pulled a body out of the water.

There were hotel and motel pools with my sister when our family was on vacations. Our backyard pool during my teenage years. The Hart House Pool at UofT, which I swam every day when I was pregnant (which was the same time at which I’d become obsessed with reading books about swimming). And also the Turkish bath in Budapest, where I once went swimming a long time ago when I was pregnant but did not want to be.

And this is the impact that Leanne Shapton’s beautiful books always have on me, her own experiences or her imagined ones leaving me awash in my own thoughts, memories and questions– see my posts on Native Trees of Canada and Important Artifacts. For me, her books point away from themselves, even in their remarkableness and their beauty as objects. (Shapton is a book designer, as well as an author and illustrator.) Which is not to say that her latest, Swimming Studies, is not an incredible book, one of the best I’ve read this year. In her curious collection of sketches-cum-memoir, Shapton teases out the connections between her past as an Olympic swimmer and her present day experiences as an artist in New York City. How did she get from there to here? How do her two selves inform each other? Are they really so separate after all? How does the discipline required for athleticism inform an artist’s life?

Swimming Studies is an exercise in nostalgia, a love letter to places where we no longer belong. I was never, ever a competitive swimmer, but I remember the kids in my class who always smelled like chlorine, which made their skin flake and their hair turn green. I remember their t-shirts that said, “No Pain No Spain.” I remember Victor Davis and Alex Baumann, and in 1984 I was in the crowd at an Anne Ottenbrite Parade, celebrating her gold medal, the very first parade I’d ever seen that didn’t end with reindeer. I found it all fascinating and strange.

But I remember too having strong feelings about the logos on my sweatshirts. Shapton writes, “When I follow a trend (plastic bracelets, neon lycra), I get nervous. Mosquitos and wasps are attracted to my fluorescent-yellow sweatshirt. I spent an unhappy year in seventh grade trying to look preppy with the wrong ingredients…” She writes of her older brother, “I was always watching Derek for signs of what was possible, how to make decisions, what to like and how to tell. I knew he wanted to lose me, and I tried to keep my distance, but I wore the same Converse All Stars as he did, the same jeans…” One chapter begins, “My first visit to Ottawa was with my sixth-grade class…” I know these reference points, Phil Collins playing on the car radio. Watching through windows for your mom’s headlights, for her car to pull into the lot to take you home.

Swimming Studies is a difficult book to explain, and I’m glad that I get to review it in my blog so that I don’t necessarily have to. That I can simply say that the whole thing just works, for no reason I can really fathom. Leanne Shapton writes about ponds and pools she has known– the Hampstead Heath Ladies Pond, the pool at the Chateau Laurier, the baths in Bath, and so many others. She writes about morning practice: “Ever present is the smell of chlorine, and the drifting of snow in the dark.” A many-page spread displays her extensive bathing suit collection. She includes drawings of her teenage swim teammates, with brief biographies for each: “I’m not crazy about Stacy since noticing that she copied onto her own shoes the piano keys I drew on the inside of my sneakers.” About quitting swimming twice, and how the swimmer inside her cannot be shaken, and how she’s had to learn to live with her. Paintings of pools, of figures in the water. A chapter on her obsession with Jaws, with Jaws as metaphor. Her fascination with athletics, with athletes who aren’t champions: “Their swims, games, marches aren’t redemptive. Their trajectories don’t set up victory.”

It works, and maybe you have to understand the lost world that she’s conjuring in order to really get it, or maybe you just have to understand the nature of lost worlds at all.

**

I bought my copy of Swimming Studies on Saturday on the way home from a splendid afternoon at the Christie Pits pool, the pool that this wonderful hot summer has given us many occasions to appreciate. Our visit was particularly notable because the water slide was on, and also because it was the debut of my brand new bathing suit which I’ve been waiting all summer for. It’s my mail-order bathing suit, an idea that was always going to turn into a saga. It’s the Esther Williams Class Sheath, which I purchased after seeing it endorsed by trusted bloggers at Making It Lovely and Girl’s Gone Child. It arrived too late for our vacation, but actually fit (albeit snugly, requiring me to do a funny little dance in order to get into it). And it’s lovely, so I was happy to have an opportunity to wear it when summer came back to us this weekend. We didn’t bring our camera when we went to Christie Pits, so I decided to wear my suit again the next day at the wading pool, just so you can see how excellent it is. No ordinary bathing suit would drive me to post a photo of me wearing it on the internet, let me tell you. So maybe this is the beginning of a new internet meme called Book Bloggers in Bathing Suits? Like all proper book bloggers, however, with our sensitive skin and lack of propensity for pin-up-ness, I’ve had to delay this big reveal for a week or two because I was waiting for a rash to go away.

I bought my copy of Swimming Studies on Saturday on the way home from a splendid afternoon at the Christie Pits pool, the pool that this wonderful hot summer has given us many occasions to appreciate. Our visit was particularly notable because the water slide was on, and also because it was the debut of my brand new bathing suit which I’ve been waiting all summer for. It’s my mail-order bathing suit, an idea that was always going to turn into a saga. It’s the Esther Williams Class Sheath, which I purchased after seeing it endorsed by trusted bloggers at Making It Lovely and Girl’s Gone Child. It arrived too late for our vacation, but actually fit (albeit snugly, requiring me to do a funny little dance in order to get into it). And it’s lovely, so I was happy to have an opportunity to wear it when summer came back to us this weekend. We didn’t bring our camera when we went to Christie Pits, so I decided to wear my suit again the next day at the wading pool, just so you can see how excellent it is. No ordinary bathing suit would drive me to post a photo of me wearing it on the internet, let me tell you. So maybe this is the beginning of a new internet meme called Book Bloggers in Bathing Suits? Like all proper book bloggers, however, with our sensitive skin and lack of propensity for pin-up-ness, I’ve had to delay this big reveal for a week or two because I was waiting for a rash to go away.