May 16, 2025

Secret Good Things

Last October, I had a mammogram, and I didn’t tell anybody. Not out of shame, or secrecy, but instead out of a fit of subversion. Because of social media, there is now a template of how we’re supposed to perform these things, maybe a hospital gown selfie, or a waiting room shot, and there’s even a script for how the caption should go, and I just didn’t want anything to do with any of it, and this is how I’m feeling about putting most of my life on the internet these days.

Which is how some people have felt about putting their lives on the internet since the beginning of time, perhaps most wisely, but it’s a departure for me, someone who’s been putting myself out there since I started my first blog 25 years ago this October.

25 years, which is more than half my life, and almost the entire span of the century so far, enough time to know that everything is always changing, whether it’s the internet, the world, or me, and the best thing about my blog is how it has captured all of that movement I might not have noticed otherwise: who on earth was that girl anyway, just post-teenaged, posting angst filled pop culture lyrics on her Diaryland site, which, blessedly, remains only accessible via internet archives if you know where to look? How was the damask wallpaper installed on my Blogspot blog ever considered aesthetically appealing? Who was that lady yammering on about Mommy bloggers before she had kids? Or the one who wrote about how she’d finally got her anxiety under control in a lovely post dated February 2020 (and ha-freaking-HA)?

For a long time, I considered social media to be micro-blogging, and it came naturally to me, I figured, because I’d been blogging for so long. I counselled people about the advantages of living life online—it’s a way of showing your process, making connections, being human, an exercise in authenticity. Which I think was true with blogs, and maybe it still is (blogs are fundamentally obscure; well-known blogger is an oxymoron), and I continue to show up on my blog and be more honest and curious and sometimes messy there, just because of my confidence that almost nobody is reading and so I’m not performing anything.

But it’s different on social media, these platforms underlined as they are by algorithms, the dreams and whims of billionaires, and a tendency to indulge everybody’s worst tendencies.

It was the Black Lives Matter black squares that did me in, back in June 2020. And perhaps this was my old-school blogger ethos showing, but the murder of George Floyd was a occasion that called for extreme thoughtfulness and introspection, work we had to do in our minds and our bodies instead of performing in public by rote, adding a black square to your grid because it was expected. When blogging began, doing what everybody else was doing was anathema to the project, and instead we were supposed to provide our own perspectives, the kind of “take” that no one else could offer, nothing general about it (and not necessarily a “hot” one either).

And it was the pandemic too, the way I felt it necessary on social media to perform my values and politics around everything, which seemed important because the stakes were so high—literally life and death, and preventing our health care system from being extra-overwhelmed, and encouraging the normalization of public health measures—although this compulsion was also a manifestation of my anxiety (amplified by the cacophony of voices I’d encounter online and was desperate to synthesize) as well as an awful lot of pressure to put on one human person (and eventually, that pressure broke my mental health).

I’d long supposed that social media could be an exercise in immediacy, in paying attention, and living in the moment. On Instagram, the insta was the point. I’d also thought that the benefit of a life that looks cool on Instagram is that you end up with a vase of tulips on your kitchen table and delicious meals at a good restaurant that you get to eat once a photo is taken. The pressure to show up on social media can push us out into the world, make us try new things, and go to new places, and I’ve been selling myself this idea for a long time, but for me—on social media at least—it eventually ceased to be wholly true.

It was when I would be someplace beautiful and thinking more about how great it would look on Instagram than actually being there that it began to feel icky. Or if I’d failed to get a good shot, or had no photo at all, and it seemed like the moment had been wasted. The overwhelming pressure I’d feel to include a record of everywhere I went, and everything I ate, and everyone I saw, because otherwise, it was like none of these things had even happened. And I’m going to say that I experienced some of these same pressures back when I was avidly scrapbooking my teen years before the internet even existed for me. Possibly this is a ME problem, instead of a problem in general, but it definitely was a problem, and a habit that I had no idea how to break.

Contrary to what I’m saying here, I actually have good boundaries when it comes to the internet. When I go on vacation, I never look for a wi-fi password. My phone goes to bed a couple of hours before I do every night. I don’t have a good data plan, so I don’t have access to the internet much of the time when I’m out in the world, and these are choices I make most consciously. But it was still not enough , and I’d have to push it further. I was tired of feeling divorced from the moment, and as though I were living my life for an audience. Authenticity is a fine thing, but I was feeling as though I were constantly submitting to scrutiny. I was also exhausted by a politics that was demanding this or that, us or them, just a further entrenchment of divides that were already so dangerous. This was around the time I started adding “avid human” to all my online bios, instead of a series of hashtags. It was an assertion that I, like you, contain multitudes, and that the work I do in my own head and in my own community might be far more important than anything I happen to be inputting into the billionaires’ algorithm machines (substack included!).

This post I wrote at the beginning of 2024 was the beginning: “In 2024, I want to be more thoughtful…and keep more things—more the joy and the pain—just for me, and the people in my life.” Slowly, slowly, I made progress. At the end of the year, I’d removed Instagram from my phone.1 I’d kept my mammogram private, just to prove this was possible.2 I performed good deeds and people did nice things for me, and it all happened even without being broadcast. I went out for dinners that you don’t even know about. Sometimes I was happy or I was sad, but you didn’t hear about it. Other times, the sunlight fell on my table in such a way, but the point was to notice it, not to hold it. I can read a book and not follow with any kind of response, if I don’t feel like one. I’ve not posted a somewhat unflattering selfie of me in a swim cap for months now, even though I go swimming every day. I went to see the cherry blossoms at Robarts Library, and only posted a photo four days later—which in cherry blossom time is actually 760 years.

I keep thinking about Shawna Lemay’s 2020 post, “Do Secret Good Things,” and what it feels like to have some tricks up my sleeve, instead of letting it all hang out there for everybody to see. I’ve become more comfortable with not controlling the narrative, or even (and more importantly) feeling I have to. Moments happen, and I let them (I say, as though I have any power otherwise). And I’m feeling so much better for it.

The danger of this, of course, being that now I’m just performing my cessation of performance, that this is more of the same, that I’m as show-offy and self-satisfied as I ever was. I don’t think I am (I waited this long to tell you about my mammogram—surely that stands for something), but I don’t know, and maybe that’s the point.

I don’t know, and I don’t even have to.

(This piece first appeared in my Enthusiasms newsletter, which is the Pickle Me This Digest. If you’d like to receive a copy of my newsletter in your inbox every month, you can sign up here!)

February 25, 2025

February Essay: In the Air Tonight

The week after the US election, I was talking to my therapist about fathers. Not my father, but fathers in general, and about the avuncular manager at the grocery store whom I’d encountered in the bread aisle with an expression of concern on his face because there had been a widespread recall. Another widespread recall, after the one not long before it that had me tossing my fancy $5 ancient grains loaf into the garbage because it might be contaminated with metal fragments, just one more thing that made it feel like the world was going to shit, like nobody normal was in charge.

“Do you know what’s going on with this?” I asked the grocery store manager, who looked up from his clipboard shaking his head, but not despairingly. It’s just a lot, managing a grocery store, even at the best of times, and these are not that. He explained that my preferred loaf was not affected by this recall, and I said I wanted to be sure. Mainly I just wanted to keep talking to him, because of the authority of his clipboard, and how he reminded me of the actor Richard Kind.

“Basically,” I told my therapist, the revelation dawning. “I wanted the grocery store manager to be my dad.”

And with that, I finally realized why, in the wake of an election that was upending the world order, I was yammering on about ancient grains and grocery stores, and I also understood the one thing I might have in common with voters who were celebrating the election result instead of mourning it.

It was all about dads, about clipboards and pressed shirts, about order and authority, and the the promise of a person (a man person) who could tell you, and even mean it, that everything was going to be all right.

(Read the rest at Substack. If you’re a long-time blog reader, I would be happy to send you a complimentary paid subscription. Drop me a line and let me know.)

February 11, 2025

Crowded Rooms Full of Happy People Doing Inconsequential Things

My most recent ENTHUSIASMS newsletter went out this morning without caveats or apologies for enthusing at a moment when so many things in the world are terrible, for the simple reason that enthusing is one of my deliberate non-reactive responses to “all this,” along with another of my great pleasures lately: gathering in crowded rooms with happy people taking part in activities of little consequence.

Gathering in crowded rooms with happy people taking part in activities of little consequence, to me, is not just an antidote to our precarious current moment, but also to the last five years, during which crowded rooms and crowds in general have often felt threatening, sometimes enough to put me off people in general, contempt breeding contempt. But I can’t have that, because it only turns me into a monster, a mirror image of the forces I rise against, so instead, I am reacquainting myself with community and connection, all the while also bringing a fresh awareness of boundaries that I didn’t used to have, which previously made things like community and connection into an awful kind of trap. (Other people are not required to love me. WHO KNEW? And I don’t have to love everyone: ALSO TOTALLY FINE. WHAAA?)

All this is not to denigrate gatherings of people taking part in activities of GREAT consequence (for example, we have an election coming up on Ontario at the end of this month; make sure you’re registered to vote!) but I actually think these inconsequential activities matter just as much. (It matters too for me not to be gathering in rooms crowded with angry people. Rage is not the fuel I need right now, and this world has enough of it already.)

So I’ve been working hard at showing up, at gatherings large and small. I’ve been inviting my neighbours for dinner and reaching out and making plans with friends I haven’t seen in too long. I’ve been making an effort to get out into the world, and be with people, even anonymously (sitting with a book and a cup of tea in a crowded cafe) to repair the tears in my own sense of the social fabric, which can’t help but go some way towards repairing that sense in others, even though I’m not even responsible for that. I’m really only responsible for me, and knowing that makes the entire project so much easier.

I want to live in a world where I trust people, where I welcome people, where I can have thoughtful disagreements with people, where I learn from people, where I am content to let people think otherwise, where I can be wrong, where other people can be wrong, where there is room enough for all kinds of different voices in all kinds of different keys.

Often literally—I’ve been in rooms singing along with strangers in a variety of different contexts lately, and I love this, that we’re making harmony, which is pretty much our job here as beings on this planet earth. But in more abstract ways as well—even riding the subway, I look around and consider what a miracle this arrangement is, all of us together, strangers in a tin can hurtling through the darkness, minding each other’s business, even ignoring each other, which is an undervalued part of city life, if you ask me.

You be you, and I’ll be me, which is also a kind of mercy.

*

This message was part of my February newsletter. To receive the Pickle Me This Digest in your inbox every month, sign up today!

January 29, 2025

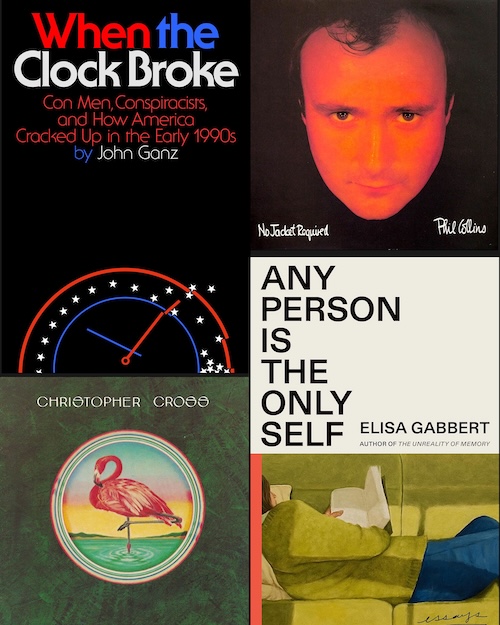

Remarkable Debuts: What I Read on my Winter Vacation

Anita Brookner, Margaret Laurence, Elizabeth Strout (#WinterofStrout), Carol Shields, Barbara Pym, and more vintage treasures (including trigonometry?)

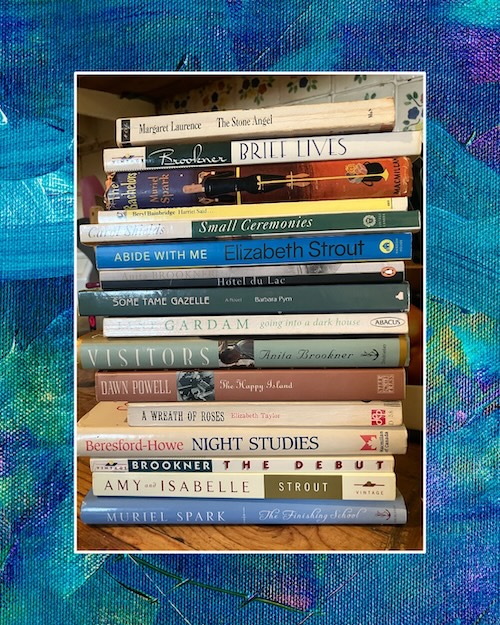

December marked the dawn of my Anita Brookner era, arriving with her first novel, published in 1981, appropriately titled The Debut (although only in North America—it was A Start in Life in her native UK). My copy was a Vintage Contemporaries edition obtained at the Vic College Book Sale, and when I started reading and loved it immediately—the opening line is “Dr. Weiss, at forty, knew that her life had been ruined by literature.”—this was the solution to a grave problem that had plagued me in 2024.

The problem being that I’d spent the last 20 years buying all the books in secondhand bookshops and now there was nothing left, save for The Pilot’s Wife, A Million Little Pieces, and a box of dusty National Geographics. How dispiriting to visit the Oxfam Bookshop in Lancaster, UK, last April and emerge with bubkes, especially after years of the seemingly infinite backlists of Laurie Colwin, Barbara Pym, Margaret Drabble, Penelopes Mortimer Lively and Fitzgerald, Alice Thomas Ellis, Jane Gardam, (most recently) Sue Miller, and so many favourites.

I don’t know why I’d never read Anita Brookner, especially since secondhand copies of her books are widely available. She hadn’t started out so long ago that the books aren’t still around, but not so recently either that they’d come back into vogue. She was prolific, publishing a novel annually for 22 years after beginning at age 53 (and she’d publish two more, in 2005 and 2009). She was also spoken of in the company of Barbara Pym, as Brookner similarly wrote mostly of women outside the conventions of marriage and motherhood.

But maybe I had been put off by how any comparison between the two writers always slighted Pym (“Brookner’s ambitions exceed those of Pym’s genteel novels of manners and place her outside that genre…” from the back of my copy of The Debut). I’d also been intimidated by Brookner’s author photo and how her hair was like a helmet, and I’d had this impression that she was a generation younger than she actually was (she was born in 1928), mostly because her author photos never changed or softened as she aged, and certainly her hair didn’t.

And then I discovered that I had read Anita Brooker before. After falling in love with The Debut, with its curious combination of humour, pathos and absurdity, and then buying and reading her 1997 novel The Visitors (a beautiful hardcover first edition, though I didn’t like it as much as The Debut; I read somewhere that Brookner’s books might have been stronger had she slowed down a bit, and maybe it’s true), I returned to the secondhand bookstore and bought two more Anita Brookners—thereby robbing myself of one of my great year-end pleasures, which is seeing my to-be-read shelf depleted, but here in my Brookner era it only grows. And that is fine.

One of these later purchases was Brookner’s Brief Lives which, I realized (via a keyword search in my blog archive), I’d read and reviewed more than a decade ago, along with her novel Look at Me the year before that, even declaring, “There is no charm to Anita Brookner, but this, of course, is why her books [are meant to] seem more literary.” Which sounds clever, but I can’t take credit, having no recollection of the book or even its reviewer, and also disagreeing with the assertion.

And isn’t this why rereading is essential? Because of the way that our selves are formed and reformed, and how the reader I was in my early 30s was unequipped to recognize Anita Brookner’s wry and subtle charms—oh my goodness, her Booker Prize-winning Hotel Du Lac, the book I picked up next and wholly adored!—which perhaps a reader has to be in at least her mid-40s to properly understand.

It would have been a tragedy if I had remembered not being fussed about Anita Brookner, and given up on her work altogether.

This is from my January essay on Substack. Paid subscribers can read the rest here. And, as always, if you’re a longtime blog reader and can’t manage the subscription, drop me a note and I will be all too happy provide you with a complimentary one!

December 2, 2024

“All I Want Is Everything”

I don’t remember the first time I read The Diviners, but whenever it was, most of the richness of the novel was surely lost on me. February 2000 is the date inscribed below my name on the inside page of my New Canadian Library Edition, from a second-year Canadian fiction course in university, but I’m sure I read it at least once before that too. We’d studied Margaret Laurence’s earlier novel, The Stone Angel, in high school English, a curiosity in the curriculum—I’m not sure that 17-year-olds were ever that book’s ideal readers. And to my (very young) mind, for a long time, there wasn’t a clear distinction between its nonagenarian protagonist Hagar Shipley and The Diviners’ Morag Gunn, both of them untamed women with ugly first names, their characters rhyming (hag and rag), both past their prime, unfathomably elderly.

I reread The Diviners again in 2006, according to the second date on the flyleaf, when I was in my mid-20s, an experience that left no impression. My favourite of Laurence’s Manawaka books has always been The Fire Dwellers, a story of 1960s’ suburban housewife ennui, a novel that’s closer to my cultural and pop-cultural sensibilities, and I’ve returned to it a few times more recently. Unlike The Diviners, which stayed up on the shelf until after I’d gone to see the stage adaptation at The Stratford Festival in September (it was magnificent!) which blew my mind with the revelation that Morag Gunn is 47.

ONLY 47, which is to say in the prime of life. In my early-20s solipsism (um, as opposed to my current mid-40s solipsism!) I’d missed this entirely. Morag doesn’t help the cause by proclaiming, “But the plain fact is that I am forty-seven years old, and it seems fairly likely that I will be alone for the rest of my life…” at one point, sounding like some washed-up old hag(ar), although she doesn’t necessarily mean the fact of her solitude as a bad thing, something I didn’t understand before.

And this was just one of the many things I didn’t understand before, until I reread The Diviners again this month at the age of 45, my first experience of truly being able to access its depths and its wonders…

(The rest is available to paid subscribers on my Substack—you can read it here. And I still have two free substack subscriptions available to my blog reads. Send me an email at klclare AT gmail DOT com to claim one!)

July 24, 2024

Summer Reading

Earlier this month I wrote a substack post (available to all readers) about Catherine Newman’s SANDWICH as an ideal beach read. You can read it here!

Paid subscribers can read my July essay, “How to Build a Summer Reading List,” which went up yesterday, and you can read it here. (Thank you to new subscribers! It means everything.)

And finally, there’s a Canadian Goodreads giveaway of my novel ASKING FOR A FRIEND, which makes for an ideal summer read, I must say. Enter before July 29 for your chance to win!

May 31, 2024

Something With Good and Evil

My May essay is about rereading Toni Morrison’s Sula, reconsidering this book about female friendship that is so much more than “just” a book about female friendship—but maybe that’s the thing about great books about female friendship—they’re always about so much more, because that’s the tangle that life is. Read it here! Many thanks to new subscribers—writing these pieces is so satisfying and you’re the icing on the cake.

May 1, 2024

The Road to England, Via Leicester

My first Substack essay for paid subscribers went up yesterday and I’m so proud to have created my fourth of these long-form essays, such a cool and fulfilling creative challenge. This one is about how Adrian Mole’s diaries have been foundational texts and my gateway to English culture. How I’ve never seen how the heather looks, but I learned about the Midlands, about the time I ran away to find an English husband, and how there was actually once a time when I didn’t know what a scone was. Paid subscribers can read it here. Thanks to everyone who has paid to subscribe—your support is so meaningful and helpful to me.

I have two subscriptions left for my dedicated blog readers, just to thank you for all your support of my work here. Drop me an email at klclare AT gmail DOT com if you’d like to claim one.

January 31, 2024

Danielle Steel, and the Person I Used to Be

I’ve started 2024 with the intention of doing things differently, channelling the energy I’ve been putting into social media (rendering my thoughts not only fragments, but disposable fragments) into writing one essay every month. This is the first one, and I’m so happy with how it turned out.