May 24, 2024

Ordinary Human Failings, by Megan Nolan

Are Irish writers having a moment, beyond Sally Rooney and Tana French, even? (And Claire Keegan, and Louise Kennedy, and Caroline O’Donoghue.) Here’s another, Megan Nolan, whose second book is Ordinary Human Failings, a novel that’s agonizing exquisite, beginning with the death of a toddler on a London housing estate in 1990, all local gossip pointing toward a semi-feral 10-year-old as the killer, the second child belonging to an Irish family that’s never really seemed right, particularly since the death of the mother, Rose, leaving behind her husband, John, disabled by a workplace accident; eldest son Richie, a drunk; daughter Carmel, beautiful and hardened; and Carmel’s daughter, Lucy, neglected and wild. All the pieces fitting into place, or at least that’s how it seems from the perspective of newspaper reporter Tom Hargreaves, young and striving, hoping to land that big scoop that’s going to take him somewhere far from here. He ends up with the family and uses whatever tools he has on hand to get them to hand him their misery, share the pitiful story of how they all ended up like this, but he’s not as savvy as he seems, which is to say that he just doesn’t get it (in both senses) and Nolan shows each family member’s most vulnerable and private selves, the tender bits that nobody else has ever witnessed before, and that nobody like Tom will be able to exploit. Nolan renders these people as tragically, achingly human, their stories only ordinary ones, so the title goes, but this novel itself is quietly magnificent.

May 22, 2024

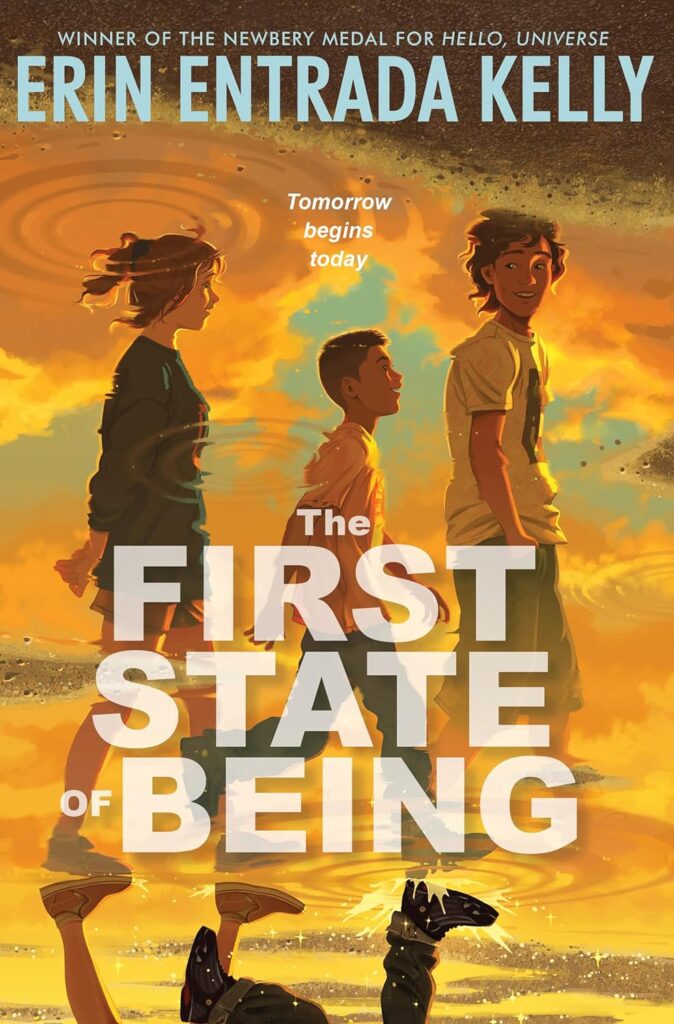

The First State of Being, by Erin Entrada Kelly

“I know it doesn’t seem glamorous or interesting to you right now… But that’s because no one realizes they’re living history every minute of every day. Sure, there are big moments, like the first Black president or the first trip to Mars and Jupiter, or the first STM. But the truth is, we’re making history at this very moment, sitting on this couch together… Every breath we take, we’re contributing to history.”

THE FIRST STATE OF BEING is not actually the first book I’ve read by Erin Entrada Kelly, whose 2017 novel HELLO UNIVERSE was (in addition to winning the Newbery Medal!) a pick for the parent-child book club I was in with my eldest a few years ago. I borrowed her latest novel from the library for her sister, who is (almost) 11, and didn’t have plans to pick it up myself until I leafed through a few pages and started reading the top of Page 43 where it says, “And it’s 1999! The best year!… The Backstreet Boys! Britney Spears! Fight Club! The Matrix! Ricky Martin, livin’ la vida loca! I mean, yes, I was goaded, but the truth is, I WANTED to see it. All of it. Especially the mall. Ordinary, everyday life. Weird?”

And there really was something about 1999, the music, the vibe, and it’s not JUST that it was the year I was 20. If you don’t know what I mean, check out Rob Harvilla’s essay, “How ‘Summer Girls’ Explains a Bunch of Hits—and the Music of 1999.” It was the summer I first learned how it felt to anticipate that incredible key change while belting out “I Want It That Way,” which I’ve been singing ever since, and I honestly never thought at the time that such an ordinary song, an ordinary moment, would prove so eternal, would become another kind of time machine. (The funny thing about growing up in the 1990s in a North America with Francis Fukuyama-inspired headlines and that Jesus Jones track playing in the background is that I really did feel history was everything that had come before us, and that somehow we had managed to be living outside of it.)

THE FIRST STATE OF BEING is set in the summer of 1999 in an apartment complex in Delaware where 12-year-old Michael is hiding stolen canned goods under his bed in preparation for the world falling apart when the calendar flips to the new millennium, Y2K being just one of his many anxieties—his mom is working three jobs and struggling to pay the bills, and Michael feels responsible for the stress she is under. Even worse, she insists on hiring him a babysitter a few days a week, even though Michael is too old for a babysitter, and even worse than that is that Michael has a crush on his babysitter, the brave and brilliant Gibby, age 16, a Neil Diamond cassette jammed in the deck of her 1987 Toyota Corolla.

And then the two of them meet Ridge, a strange-seeming kid hanging out in the courtyard, and when he tells them that he’s a time-travelling visitor from 200 years into the future, his story actually tracks. Ridge is obsessed with 1999, obsessed with seeing a mall, though he refuses to supply the information Michael really wants to know about just how Y2K works out. It turns out that clinging to certainty might not be the answer to anxieties about the future, especially because that leaves no room for the unexpected, and there is all kinds of great wisdom woven throughout the text about doing the best we can with what we’ve got today (which includes looking out for and taking care of each other).

“The first state of being… That’s what my mom calls the present moment. It’s the first state of existence. It’s right now, this moment, in this car. The past is the past. The future is the future. But this, right now? This is the first state, the most important one, the one in which everything matters.”

I LOVED THIS BOOK. And then I made my husband read it, and he loved it too. We’ve both adored Connie Willis’s Oxford Time Travel series, and this novel gestures toward their ethos in a subtle way, and I was also pleased to find an obligatory reference to Back to the Future and concerns about the Space-Time-Continuum, of course. Though THE FIRST STATE OF BEING’s treatment of time travel was also pretty fresh in its own right, transcripts from Ridge’s time and excerpts from contemporaneous books and articles about time travel and the technology behind it interspersing the 1999 chapters, these additions enhancing the novel and leading to more than a few moments when everything *clicked* and I started shouting with excitement as the pieces came together.

Too many science fiction books (especially for grown-ups!) become unwieldy, narratives overburdened by world-building, which makes the brevity and light touch of THE FIRST STATE OF BEING—a story built on all things huge and existential—all the more remarkable. How Erin Entrada Kelly managed to fit so much so easily into a story so brief must have been an exercise in essentiality, but she struck the balance exactly right, and I really can’t stop thinking about all it.

May 22, 2024

Gleanings

- It’s the constant thread that’s run through my musical taste since I was a kid. Sure there are exceptions to the rule, but the broad strokes of my music collection are generally in the guitar and feelings vein. The folk music I grew up with and still love? Guitar and feelings. The indie bands and Canadian rock I loved in high school? Guitar and feelings.

- But beyond that, even in the context of safe and trusting relationships, we’re simply not in the habit of asking about emotions, listening to the answer, and responding accordingly.

- A lady comes into order a book “Chemistry…” (me, uh oh we won’t have this) “… Lessons, by Bonnie Garmus.” Of course we have that. Customer is surprised and delighted, makes her purchase and then has a small coughing fit. She says “I’m not ill!” from the doorway and I reply, “it’s fine” and then I wonder what on earth I mean – it’s fine if you are ill? it’s fine if you’re not. I’m sorry I said “it’s fine” when what I meant was “do you need a glass of water?”.

- Yesterday was the best day ever. Perfect in fact and, whilst out, I knew that my next blog post would be joyful. It is amazing how much of nature’s peace we absorb if we only give it the chance to work its magic. Whatever happens in the next few weeks and months we’ll face together, but it is not now, nor then, going to occupy so much of my thought process.

- For the first time in weeks, it felt like an opening. Fresh sky, cleansed from last night’s rain, birdsong. Do you want me to set up a target, he asked, and I thought, yes, that’s exactly what I want: my feet in the moss, the bow in my hands, string pulled to my cheek, the arrows alive in the air.

- It was not the noise of the door that woke him; it was my absence. He does not sleep well when I am not beside him. Whenever I get up in the middle of the night and take too long, he comes looking for me.

- Nothing is ideal. I love that too, the reassurance of it. I mutter this phrase to myself a lot — “This is not ideal!” —- and not negatively, but encouragingly. I mean it as a form of freedom. Nothing about this is ideal. (And it does not need to be.)

- On a day when thoughts go to maternal places I remember how my mother liked bluebirds and flowers on her cards, the more saccharine the better and preferably store-bought. Nothing made at school with macaroni thankyouverymuch. So I grew up with a certain amount of seasonal card anxiety and my teeth still ache at cardboard bluebirds but what’s more interesting is how this stuff finds its way into our work.

- I nipped to the shops mid-afternoon to get some chemist-y stuff and a few little treats (a packet of Smarties, a packet of Tina wafers). While I was there, a mother with a baby in a pram and a preschooler beside her stood at the register ahead of me. The preschooler said to the shop lady “look what i can do!” and then she trilled her tongue quite loudly and very proudly. The shop lady was obviously amazed.

- Munro writes about ordinary women with extraordinary complexity. In one interview, Alice Munro said she didn’t think anyone was, in fact, ordinary.

May 15, 2024

Death By a Thousand Cuts, by Shashi Bhat

The first time I read Shashi Bhat was her Journey Prize-winning story “Mute” in 2018, and I remember just feeling captivated by the narrative voice, being struck by the singularity of her character’s experience, and yet noting how much I could identify due to the specificity of her perspective and the choice of such essential details. A scenario that really gets under the skin, that’s really “cringe,” as the kids say. A little “Cat Person,” a little Sally Rooney, altogether timely in the age of #MeToo, but also I just read it and wanted more of literature that can affect me like that, and thankfully Bhat delivered with The Most Precious Substance on Earth, her excellent 2021 novel-in-stories, and now with her latest, Death By a Thousand Cuts, which is just devastatingly devourable and I read in a single day.

Naturally, every time I think of this book, the Taylor Swift song of the same name starts playing in my head, which I’m not sorry about. And I don’t know if Shashi Bhat is a Swiftie, but her literary preoccupations are not different from those in Taylor’s tortured poetry—her stories are about seeking and not finding, about the tedium of dating, about longing and wanting and disappointment, but there’s also a brutality to them too, a sting. (Let the wasp on the cover of the book be a warning.) As I was reading this book upstairs, I kept having visceral reactions to the stories, gasping in dread and horror, and members of my household were concerned for my well being, which says a lot for a book, that they can affect one in this way.

These are stories that will be appreciated by readers who aren’t even sure that they like reading short stories. And while I know short story lovers bemoan the form’s lack of wider and/or commercial acceptance, I get it too—as a reader I want something immersive, something deep and lush to sink into and get lost inside, the way I can inside a novel, but in these stories, I really can, so much richness, so much texture. As satisfying as the dripping fruit of the cover, but even better, because I can read them over and over again.

May 14, 2024

Monsters, Martyrs, and Marionettes, by Adrienne Gruber

As I noted in the introduction to my Bookspo conversation with Adrienne Gruber, I’m not as preoccupied with notions of motherhood these days, or with essays about of motherhood, certainly not as much as I was back in the day when I was publishing my own anthology of essays about motherhood, when I was positively obsessed, and felt like I was working out pressing and essential existential questions with this obsession. The most surprising and disappointing revelation of that experience (along with many others that weren’t disappointing at all) being that motherhood is niche, never mind that everybody everywhere was born to a mother once upon time. But considerations about motherhood themselves are not as fascinated and universal as I’d supposed they’d be back when I was young, starry-eyed, naive and about to publish my first book. (Goodreads reviews for my most recent novel include comments from readers who were disappointed that motherhood factored so strongly into my book, and therefore they found themselves unable to relate to the story.) I think too about what older writers must have thought when I was in the heart of “discovering motherhood” era. And I’m not helping the cause by having now considered motherhood discovered and conquered, because soon it will be a decade since I last changed a diaper. But now Gruber’s essay collection Monsters, Martyrs & Marionettes has gone and got me right back into the thick of it. It’s tapped a nerve. “Pouring off of every page like it was written in my soul.”

There is an essay in this book, “A Route That Does Not Include Your Child,” that is the nonfiction version of the “Hot Cars” chapter of my novel, ASKING FOR A FRIEND. Gruber and I both, I suppose, too attuned to tension, to risk, to possibility (though it’s our job as writers), reading Gene Weingarten’s 2009 article “Fatal Distraction” in the Washington Post with meticulous attention. From the first page of my novel, “Parenthood, Jess observed from her perspective smack dab in the eye of the hurricane, was—if you were lucky— like friendship, a story without end. The alternative too awful to contemplate. But what this also meant, of course, was that it never stopped, there were no breaks from the possibility of something new and worse to worry about around every single corner.”

And this is the neighbourhood that Gruber is exploring in her essays, writing about the various ways that bringing life into the world is tangled with death, dead pigeons on the sidewalk. She writes about her pandemic pregnancy, about the challenges of unruly toddlers and being able to hold a child’s gigantic and ferocious feelings, about being stuck in a two bedroom apartment with small kids due to wildfires that have made the air outside unhealthy to breathe. She’s writing about legacy, about her own struggles with mental illness, and those of her scientist mother, and her grandmother’s cognitive decline. About how essays of motherhood turn out the essays about everything, about the most elemental parts of life itself, milk and sweat, and then a reviewer will turn around and write something like, “This dark comedy is not for the squeamish,” and question who would want to read a book like this.

Anne Enright has called motherhood “the place before stories start”, describing her surprise at finding it was not the sort of journey that one could send dispatches home from. I read Enright’s memoir MAKING BABIES when I was pregnant with my first child, and a decade and a half later I understand what she means. I’d never envisioned how those early days would come to seem like a journey I now cannot imagine having ever taken. “Did we really go through that?” Otherworldly. But this only makes writing down how it was all the more important, because otherwise it would be impossible to remember any of it in that unbroken sleepless blur.

May 9, 2024

The Game of Giants, by Marion Douglas

I loved Marion Douglas’s novel The Game of Giants, though I’m not sure where to start in telling you about it. The back of the book describes the story as beginning with narrator Rose and her partner Lucy in the early 1980s discovering that their son Roger has developmental delays, his abilities marked the third percentile, which sends Rose back into her own history to explore when things went awry, which was early, because Rose as a character is pretty off-beat herself, and so is the narrative. But I’m not actually sure that this is what the story is “about” at all, and instead have a sense that this is a novel intent its own unique trajectory, intent on the propulsiveness and sharpness that results from Rose’s off-beats, and the terrific momentum created by her narrative voice and the remarkable ways that (in her experience) one thing leads to another, questionable choices culminating in a rich tapestry of experience, insecurities, lessons and longings. This novel is such an achingly hilarious story of tender humanity, with Munro-country vibes and the literary influence of Alberta, and yes, unconventional motherhood is where we finally arrive long after the runaway train has left the station on the wildest of rides, Rose struggling to accept the extraordinary reality of her son because she’s never been able to accept the reality of herself. But the reader does, just as Rose’s long-suffering partner Lucy does, Rose Drury a literary creation to fall in love with, made up of foibles, heartaches and broken parts like nobody else is, just like everybody else is.

May 7, 2024

Stories from the Tenants Downstairs, by Sidik Fofana

“But what’s sad in this whole thing is Wild One ain’t the criminal here. No, no, no. He jus a dude who did suttin. The criminals is us people around him, the people watching someone shake someone else awake from a dream and not doin nothin to stop it.” —”The Young Entrepreneurs of Miss Bristol’s Front Porch.”

Reading Sidik Fofana’s debut Stories from the Tenants Downstairs was especially meaningful for me because my friend B. recommended it to me when I was staying at her house last week, and she reads my book recommendations all the time but it’s not so often that I get to return to the favour. And what a rewarding favour this was, 8 stories from the perspectives of residents of a Harlem apartment building whose owners are pushing tenants down and out in a project of redevelopment and gentrification, all this the quiet backdrop to the foregrounded experiences of characters ranging from Ms. Dallas, a teaching assistant (who moonlights doing security at the airport); her son Swan whose friend has just come out of prison and who imagines that everything has changed with the new Black president; Mimi, struggling to get enough money to pay her overdue rent; Kandese, who we meet first in Ms. Dallas’s class, whose father dies while they’re living in a shelter; Darius, venturing into sex work and notorious after a run-in with his favourite celebrity goes viral; Najee, another student in Ms. Dallas’s class, whose scheme to make money by dancing on the subway has tragic consequences; Quanneisha, a top gymnast turned drop out who has come to face a world she’d thought she’d left behind; and finally Mr. Murray, the old man who plays chess outside of the restaurant across the street around whom the community rallies when he’s forced from his spot, but he doesn’t respond to their good will in the way that he’s meant to.

And subverting expectations is what this book is all about, in terms of the characters, but also the stories themselves, each of which comes with the most devastating pivot, sometimes on an epic scale, sometimes unbearably subtle (the push of an elevator button at the end of one story that I will never get over). As a reader, I want things to work out for these characters, but Fofana, a public school teacher in New York City (as well as a celebrated short story writer out of the gate—not everybody gets a blurb from Lorrie Morrie), does not give us the satisfaction, the catharsis.

Instead, the reader sits with the discomfort, with the injustice, a situation as intractable as those of these characters who are part of a system that was never built to serve them. Sometimes, often, this is how it is.

May 3, 2024

Not How I Pictured It, by Robin Lefler

I read a huge pile of excellent books in February as I was recording interviews for the BOOKSPO podcast, and now that those books are out in the world, I have some catching up to do in terms of posting about them. And one of these is Robin Lefler’s second novel NOT HOW I PICTURED IT, which I just loved with my whole heart. In my conversation with Lefler, she mentions how life itself is stressful enough and therefore, in her fiction, she strives to give readers a holiday from all that and provide fun and pleasure instead, which she definitely accomplishes, but I also want to emphasize that this book is so good. That excellence and being a pleasure to read can go hand-in-hand, as they do in this “shipwreck rom-com” (I didn’t even know that was a thing!) in which the cast of a 20-year-old teen drama en-route to their reunion show end up stranded on a desert island. A great cast of characters with complicated ties to each other (both spoken and otherwise) have to come together to survive, and also figure out who among them is the traitor who instigated this disaster and might still be putting them all in even more danger. Protagonist Ness—who fled show biz years ago and now lives in Toronto unclogging drains in the apartments she owns—is definitely regretting her instincts to avoid being a part of the reunion project in the first place, although the chance of rekindling her connection to her dreamy ex-boyfriend Hayes means: it’s complicated. Funny, sharp, and full of heart, I loved this book.

May 1, 2024

Who By Fire, by Greg Rhyno

In his excellent, riveting, heartful and hilarious second novel, Who By Fire, Greg Rhyno pays tribute to the fact that all the best classic detective novels always include some dame. Although his dame is not just any dame, instead Dame Polara, truly an original, only daughter of legendary PI Dodge Polara, whose brain is now scrambled after a stroke. If elder care wasn’t stressful enough, Dame is recently divorced, her latest IVF round has failed, her dodgy landlord keeps demanding she catch up on rent bills she can’t afford, and her straight job at Toronto City Hall working with heritage preservation is starting to seem pretty futile, particularly as a string of arsons take down one listed building after another. In spite of her best instincts, and out of desperation, Dame finds herself taking on a domestic case on her dad’s behalf, though she’ll be performing the investigation herself, which shouldn’t be so hard, right? After all, she’s the kid whose dad used to lock her out in the cold in order to deliver essential lessons in lockpicking, and she’s tagged along on all his stakeouts. But it turns out the case is connected to something sinister afoot in the city, and the true culprit is closer to home than Dame will ever imagine, putting her in serious danger, and forcing her to rely on her wits when the stakes have never been higher. I loved this book. A pitch-perfect pleasure.

April 30, 2024

Lightning Strikes the Silence, by Iona Whishaw

There’s not much I love better than a return to King’s Cove, the bucolic hamlet near Nelson, BC, where the fictional Lane Winslow makes her home after a tumultuous WW2 during which she’d served as a special agent, utilizing her quick wits and affinity for the Russian language. When Lane arrives in 1946, England left behind her, she’s envisioning a quiet life, a chance to dedicate herself to writing, a retirement of sorts, even though she’s still young herself, but it seems that fate disagrees, as she stumbles across a body and manages to solve the crime, in partnership with the Nelson Police Department, a partnership that’s solidified with Lane’s relationship and eventual marriage to Inspector Frederick Darling a few books into the series. And now we’re on Book 11, Lightning Strikes the Silence, and it seems that Lane’s life hasn’t been quiet for a moment, and is even less quiet than usual when the sound of an explosion is heard high on the mountain above King’s Cove. Meanwhile, in Nelson (on Baker Street!), the local jeweller has been found dead, his office ransacked, and Inspector Darling is a bit pleased about having come upon his own corpse for once, without his dear wife’s involvement, but it won’t be long before Lane is embroiled in the case as well, in addition to caring for a young Japanese-Canadian child found injured by the explosion site. In 1948, with the war long over, Canadians of Japanese ancestry are still forbidden to return to coastal areas, their homes and livelihoods taken from them, and anti-Japanese racism is rampant. Will goodness triumph? Will Lane and Darling crack the case? Will Ames finally do something with that engagement ring he’s got hiding in his pocket? Book 11, and the series gets better and better. Lightning Strikes the Silence does not disappoint.