August 25, 2025

More Summer Reading

If someone wrote a book about MY summer, it would be awfully boring to read about—all glory, no drama—but oh how lovely it’s been to experience. Last week we spent another beautiful holiday lakeside, and there was so much time for everything—being a little bit bored, even. We watched a movie every day and one day even watched two (Jaws and Puss in Boots—an incongruous mix but the latter was a nice palate cleanser). And of course, there was reading.

I started off with THE HOMEMADE GOD, which is the first book I’ve ever read by Rachel Joyce, and while it didn’t blow my mind, I enjoyed it, and the depiction of the lake in particular (and swimming) made this a very good book with which to kick off my holiday, even though my lake was in Haliburton instead of Italy. It’s the story of four adult siblings from London whose lives have been defined by their father, a middle-brow but very famous artist, and how their messy arrangements and understandings are turned upside down when he marries an enigmatic woman in her 20s, and then winds up dead at his Italian villa not long after, and his purported final painting is nowhere to be found.

Next, I read THE UPSTAIRS HOUSE, by Julia Fine, which came into my life in the most beautiful way. I happened to be in a bookshop a few weeks ago and picked up this book for absolutely no reason at all, and ITS PREMISE WAS A POSTPARTUM WOMAN WHOSE HOUSE IS HAUNTED BY THE GHOST OF MARGARET WISE BROWN. I mean, WHAT?? Could there BE a more perfect premise for a book? And how did I never hear about it, and can you imagine if I’d never picked up that book at all and shared a timeline with a novel about a postpartum woman whose house is haunted by the ghost of Margaret Wise Brown and never ever read it? I cannot imagine a greater tragedy. Even better, the book was WONDERFUL, dark and literary, about an academic whose thesis on Margaret Wise Brown and her influence by modernists like Gertrude Stein is put on hold by the birth of her first child, and things get weird after that, the novel itself haunted by Good Night Moon (itself a ghost story, if you read carefully) and The Runaway Bunny, and like any good writer herself influenced by Margaret Wise Brown, Fine resists an ending that doesn’t unsettle somewhat. This book was terrific.

And then I picked up REAL TIGERS, by Mick Herron, the third novel in his Slow Horses series, which I’m really enjoying (and it’s been reported to me by reputable sources that the TV show is even better than the book!). The series subverts spy tropes (among many tropes) and is so interesting for that, though sometimes the narrative gets very in the weeds and I’m a bit lost, which doesn’t bother me so very much (this is the case for me and any spy or mystery novel, to be honest). Anyway, I’m a fan and will keep reading—though my husband is two books ahead of me and maybe read too many at once, and suggests I space them out a bit, because it’s possible to have too much of a good thing.

And then GOD HELP THE CHILD, by Toni Morrison, which kind of cemented the theme of moral ambiguity in my reading list, as all of Morrison’s works do, blurring firm lines adhered to by people who are too fond of certainty. It’s the story of Bride, born to a mother who is shocked by the blackness in the hue of her skin, and brings her up with emotional deprivation to train her for a world that is going to be hard on her, another novel that subverts the readers understanding of good and evil (that last line! Absolutely haunting…) and maybe this is the first time a reviewer has compared Toni Morrison with the Slow Horses books, but both are utterly uninterested in making their readers comfortable or confirming anything.

And then I read MS. DEMEANOR, by Elinor Lipman, whom I’ve never read before, but I found this one in a booksale earlier this year and have been saving it for a holiday. Unlike THE UPSTAIRS HOUSE, this is a not a novel whose central appeal lies in its premise, if only because the narrative is all over the place (which is kind of ironic for a story about house arrest). It’s about a woman who gets caught having sex with a junior colleague on the rooftop deck of her Manhattan apartment, subsequently losing her job and being sentenced to six months of house arrest, but it’s also about love, Polish aristocrats, 19th century cookbooks, twins and sisterhood, and the possibilities for redemption. I devoured it, and it reminded me of Laurie Colwin, which is the highest literary praise I know how to deliver.

Next up was THE BOARDING HOUSE, by William Trevor, whose novels have been a summer staple of mine ever since I bought a used copy of his 1971 novel MISS GOMEZ AND THE BRETHREN for 10 cents in the Presquille Provincial Park park store. His works are so wicked and irreverent, his earlier books in particular, a bit of a Muriel Spark presence of the devil sensibility (Toni Morrison would concur). This 1965 novel was his third book, the story of a ragtag group of tenants in a London boarding house whose plans go awry when the owner of the house suddenly dies and his will leaves two very incompatible tenants in charge of everything—a surefire recipe for chaos, which transpires. My one reservation about this book was the single character of colour, a Nigerian man called Mr. Obd, who is not gifted the same complexity as his fellow characters, who is rendered simple and childlike (and his physical features drawn in racist terms). It made me think a lot because ALL the characters in this book were hideously flawed, so in a way Trevor’s portrayal is a kind of equality, but Obd doesn’t get to be human in the same way, is a collection of cliches (and also the novel’s ending doesn’t serve him). This is not a reason to not read this book, which is such a wickedly good one, but it’s definitely grounds for thoughtful critique (and this is a problem I find it almost any British novel from its time which acknowledged that Black people even existed).

And then the sweet treat of a book by Mhairi McFarlane, who is one of my favourite romance novelists, her books having a wonderful complexity and depth of character. Between Us was published in 2023, the story of a school teacher whose writer boyfriend’s TV series has been enormously successful, and she wonders if this is part of the reason why their relationship feels stale, or if it would have happened anyway after a decade together. And then she watches the pilot of his new show and discovers painful details from her personal life have been included in the story, and other details make her wonder if she really ever knew him at all—but also a break-up would destroy their longtime friend group and she might be left with nothing. All of which is complicated when she’s called back to her hometown to help out in her mother’s pub, stirring up the same memories provoked by what she’d seen in the show, and making her face things she’s been hiding from since her childhood.

Followed by WE ARE LIGHT, by Gerda Blees, which I bought on impulse at a bookshop in Bancroft while we were away, and it’s a fascinating book, translated from the Dutch by Michele Hutchison, based on a true story about a commune whose members attempt to live on light and air, foregoing food, which leads to one member’s death, which is where the book begins, and the narrative uses the language of the commune of collectivity and oneness to tell a story where each chapter begins with “We are ——”, beginning with “We are night” and concluding with “We are light,” the story told from that precise point of view (which includes that of a pen, a pair of socks, the scent of oranges, the neighbours, the dead woman’s family, the detective investigating whose own daughter is suffering with anorexia which gives her work a personal edge). There is a whimsical element to the approach, but the care and precision of the perspective means there is nothing “light” about it. This is a novel about truth, understanding, perspectives, meaning-making, and also connection, the necessity of the WE (but also it’s limits). Did I buy this book because the cover fit into the very orange palette of most of my reading (DAMN YOU, MICK HERRON.) Perhaps I did, but I’m so glad I did. This was an illuminating and surprising read, and a reminder that reading off the beaten track is so often incredibly rewarding.

And my ninth book was THE MYSTERIOUS AFFAIR AT STYLES, by Agatha Christie, our audiobook for the car journey, which (as usual, being no Poirot) I was completely confused by before the big reveal, but I enjoyed the ride all the same.

August 15, 2025

Blue Hours, by Alison Acheson

I really enjoyed Alison Acheson’s moody atmospheric novel Blue Hours, a story about fatherhood, and widowerhood, and what it means (and what it takes) to keep going. It’s also the story of a marriage, Keith and Raziel’s, through which they’d both aspired to defy convention. She was the breadwinner, a successful photographer, and he was the caretaker, a stay-at-home dad to their son Charlie. All the ways in which Raziel wasn’t like anybody else were part of what Keith loved best about her, but when he begins to sort through her things after her death, he discovers there were parts of Raziel’s life that he never knew about, he starts to wonder if he ever really knew her at all. All the while their 7-year-old son is processing his own grief, and Keith has to stay attentive to that, his son’s mind a mystery as great as his wife’s had been. And grief is its own kind of terrain, something Acheson knows about from her own experience—she’s author of a memoir about her husband’s death from ALS. Time marches on, and Keith needs to find a way for him and his son to go with it, and Blue Hours is a novel about enduring, artfully and evocatively wrought.

August 14, 2025

Guilty by Definition, by Susie Dent

Lexicographer, etymologist and TV personality Susie Dent is a pretty big deal in her native UK, that renown finding its way across the pond to the point where I was stopped by a stranger on the subway this week while I was reading her fiction debut, Guilty By Definition, who asked if she was same Susie Dent from 8 Out of 10 Cats, a question I was unable to answer at the time (turns out it’s a comedy panel show, and yes, she is!), but I told him the book was fascinating. It’s a murder mystery set in Oxford that begins with a mysterious letter delivered to the offices of the famous (and fictional) Clarendon English Dictionary, a letter rife with Shakespeare references that alludes to the unsolved disappearance of the newly appointed editor’s sister, who’d also worked for the dictionary, years before, the sleuthing intermingled with rare book lore, etymological wonders, and each chapter is named for a rare and perfect word like Chapter 27’s “engouement, noun, (nineteenth century): an irrational fondness.”

I will admit that the puzzles became too puzzling for me, who couldn’t solve a cryptic crossword to save my life or even know where to begin with one, and the characters in the novel lacked much emotional depth, but if the idea of a murder mystery all about words and their meanings, and dictionaries and the people who make them intrigues you at all, then you’ll find this book a rich delight.

August 12, 2025

Kakigori Summer, by Emily Itami

“There’ll be days when the way things are will make you weep, and the fact of the world is too heavy to get out from underneath. And then other days, when you can’t believe you’re here, with people you love in the world that contains barley tea and kakigori, sun after rain, watermelons and grumpy cat, and this front door. Hikaru runs through it, in such a rush he barely has time to get his shoes on, roaring at me that it’s time to go. Sunshine catches one half of his face, and the only thing I want to tell him is to keep his face turned towards it. The light, always the light.”

Emily Itami’s sophomore novel KAKIGORI SUMMER is a beautiful summer novel about sisterhood, the story of three sisters—the eldest working in finance in London, the second a single mother in Tokyo, and the third a famous J-pop star—who together retreat to their childhood home on the Japanese coast one summer after the youngest suffers a national scandal that puts her mental health at risk. Their mother has died years before, their English father lives his own life far across the sea with a new family, and their grumpy great-grandmother is impossible to get along with, which means the sisters are on their own, the way they’ve always been, making sense of their place in the world as mixed-race Japanese, if being “haafu” means that they’ll never be whole. And the novel explores the sisters’ unique position between two different cultures and ethnicities, as well as their legacy of mental illness and secrets, moving between three different characters’ voices to tell a story that sparkles like kakigori, the Japanese shaved ice dessert.

August 12, 2025

WRITERS & LOVERS

WRITERS & LOVERS made me a Lily King fan. (I am the only person in the world who was underwhelmed by her previous novel EUPHORIA.) But I also don’t remember all that much about W&L, except that it offered a lovely reprieve from pandemic lockdown doldrums during the winter of 2020. And then @streetavocados told me that King’s forthcoming novel HEART THE LOVER has a connection to W&L, and she was wild about the new book, which seems to be sentiment among everybody who has read early copies, and so I decided I needed a refresh, to reread W&L, and I’m so glad I did. Never ever have I read such a polished story about a life that was such an absolute mess, sort of like those gorgeous absorbing illustrations in Shirley Hughes books of rooms with all kinds of stuff piled up on tables and stuffed into corners. The way she writes about waitressing too, her portrayal of Casey’s work a glimpse into another world with its own vernacular and bizarre rituals, and the gamble of a creative life, which is something I’ve thought a lot more about since I read this book the first time (when I was on the cusp of publishing the sophomore novel I was hoping would be my breakout hit). W&L is a novel about life itself, which is a crummy way to some up most novels, but with this one, I actually think it means something, a book about grief, love, disappointment, friendship, money, hope, dreams, and broken promises. The kind of art that reads as effortless. I can’t wait to read what comes next.

August 6, 2025

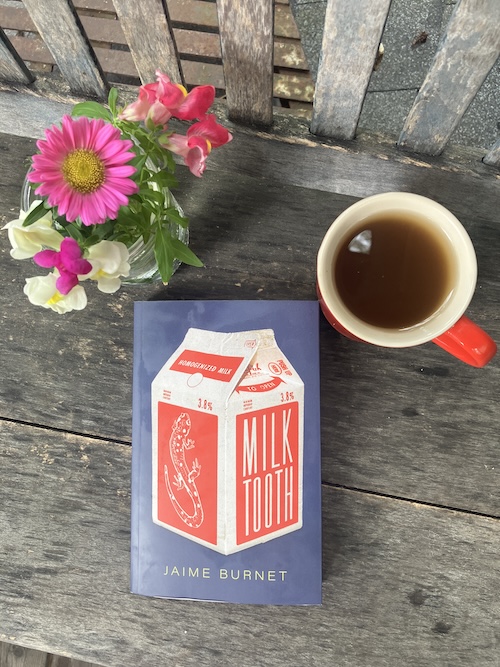

Milktooth, by Jamie Burnet

“I think the thing about life might be that it’s just hard, for no divine reason, and it will change you, with no preordained end, and it’s for you to decide whether the hardness hardens you or cracks you open.”

Oh my gosh, this novel is so good, stayed-up-past-my-bedtime good, because I had to see how it ended. (And how it ended! Wow!!). Jaime Burnet’s MILKTOOTH is absolutely spellbinding, and never misses a beat, the story of Sorcha, whose relationship with her girlfriend Chris fast becomes toxic and abusive, repeating patterns from Sorcha’s own childhood within her religious family from whom she’s been estranged since she came out to them. And while Sorcha knows that her relationship with Chris is not altogether healthy, she still wants to be with her, because otherwise what if she ends up alone and misses this one chance to fulfill her dream of having a baby?

But after she and Chris move to an isolated community in Cape Breton, leaving behind the close-knit queer community Sorcha had found for herself in Halifax, things between them only get worse, and when Sorcha finally gets pregnant, she decides there’s no way she can live with Chris anymore, fashioning an escape to the highlands of Scotland where she connects with her aunt, a midwife, who’s as estranged from the family as she is, and together they—along with Sorcha’s friends back home—begin to plot out a future for Sorcha and her baby.

With beautiful prose and gorgeously-rendered human characters (which is to say REAL), Burnet has created a story that swept me along, mesmerized. The dynamics of Sorcha and Chris’s relationship and of Chris’s emotional abuse are pitch-perfect and also hard to read in just how believable they are (how she wears Sorcha down; the gaslighting) and then just when it might be too much, Sorcha takes flight, and the triumph of her exit and everything that happens after that and also the solace and love of her friends—who are so steadfast, forgiving, and true—makes for the most moving, rich and also hilarious read. I loved it.

August 6, 2025

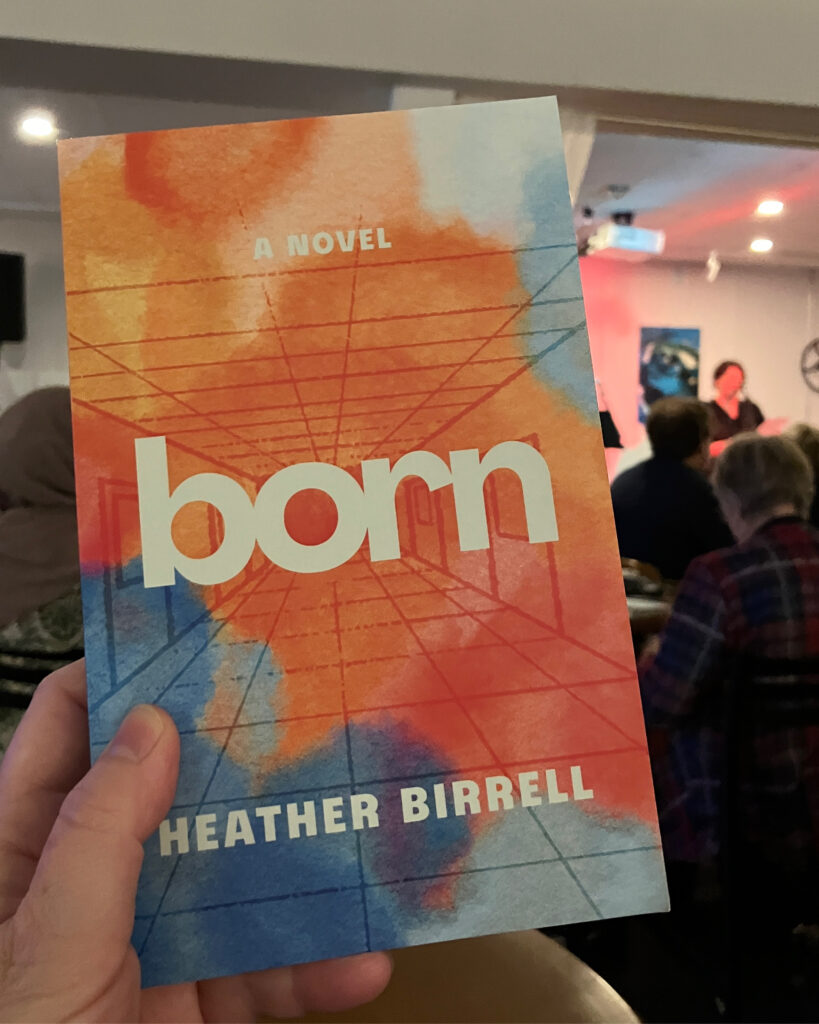

Born, by Heather Birrell

My propulsive reading recommendation for the summer of 2025 is Heather Birrell’s novel BORN, which grabbed me from the start and did not let go until its incredible perfect ending and even then not entirely. Gorgeous, compelling, fraught with tension, chasing shadows, full of light. Dazzlingly literary and unputdownable at once, this story of a high school English teacher who goes into labour during a lockdown is a polyphonic ode to caregiving, community, and public schools. It’s a fast paced read that will stay with you long after the final pages (which made me cry, they was so beautiful). Buy it! READ IT! (Or borrow it from your local library!)

August 5, 2025

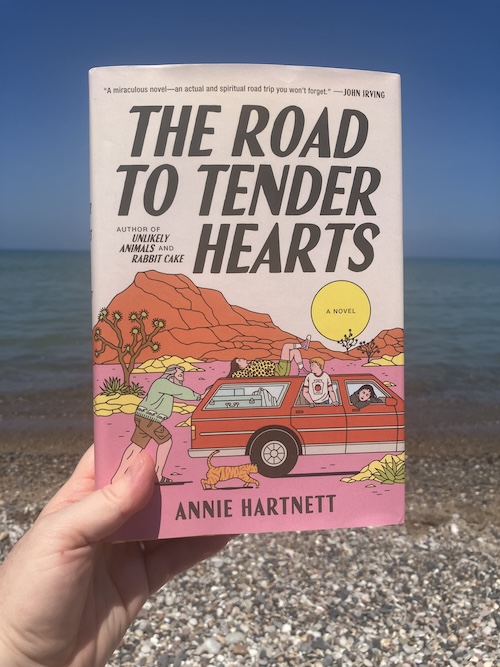

The Road to Tender Hearts, by Annie Hartnett

In the acknowledgements for THE ROAD TO TENDER HEARTS, Annie Hartnett explains that her novel was born of a challenge she set for herself around 2021: could she take all her fears and anxieties (especially about death), and her worries about not being a good enough parent or capable enough person, and turn all of these things into a novel that was FUNNY? And reader, she did, she really did, this explanation going a long way toward making sense of this totally bonkers novel that manages to be not remotely off-putting even though it’s about grief after loss of a child, childhood sexual abuse, children who are orphaned in a murder suicide, and one tragic death after another as the narrative goes on, taking its reader on a road trip from the armpit of Massachusetts down to Texas, and then to Arizona where lottery winner and prototypical well-meaning but disappointing dad PJ Halliday hopes to be reunited with Michelle Cobb, the love of his life, whose husband’s obituary has only just appeared in the local paper.

The only complication is that he’s just been saddled with the care of his grand-niece and nephew after their parents’ tragic deaths, and PJ doesn’t have a great track record for care, really. His eldest daughter drowned in a cranberry bog on her prom night 15 years before, and his youngest, Sophie, barely speaks to him now, plus he’s spent the last decade and a half drinking away his pain. And okay, I lied, that’s not the only complication, in fact, everything is a complication for PJ at the moment, in particular that his ex-wife is about to depart on a trip to Alaska and PJ won’t be able to have breakfast every morning at her house anymore. Or that PJ doesn’t have a car anymore after his DUIs. Or Pancakes, the cat, which comes along on the journey and seems to have an instinct for when somebody is about to die…

How does Harnett get away with writing a comic novel about ALL THAT? By acknowledging the best and worst parts of people, by telling the truth, by demonstrating that LOVE means telling the truth, even when the truth is that the people we love or loved are profoundly flawed or terrible.

If you’re up for a sombre book about grief, leave this one alone, but if you’re in the mood for a story that will explode your ideas about what must be treated with seriousness and reverence in fiction, then THE ROAD TO TENDER HEARTS will likely be one of your favourite books of the summer too. Thanks to Stephanie at Betty’s Bookshelf in St. Mary’s, ON, for the recommendation.

July 31, 2025

Dark Like Under, by Alice Chadwick

The story begins so late at night that it might already be tomorrow, Robin and Jonah taking chances, walking on a weir, taking chances too in being together at all—Jonah is Robin’s best friend Tin’s sometime boyfriend. They’re pushing their luck. Something terrible is going to happen, it is clear, and just what that something terrible is comes into focus at an assembly at school the next day when the reviled head announces that a well-liked teacher, Mr. Adennes, whom Robin and Jonah had met on their meanderings the night before, is dead. And everything after that seems to ricochet, the narrative full of traps and holes, shifting between the perspectives of students and teachers moving forward through the day, their understanding of the tragedy seen through the lenses of their own experiences, informed by their own traumas and heartaches, grudges and preoccupations. Tin providing as much as a centre to this tale as anything, because she’s the kind of person who draws people to her (for better or for worse), who makes “hot, empty days sparkle like broken glass,” and their teacher’s death reaches back to something terrible that happened to her years before, the image of broken glass enduring throughout the text, shiny, sharp and dangerous.

Alice Chadwick’s DARK LIKE UNDER, set in the 1980s admist the community of a grammar school in northern England, is slow, character-driven, intensely engaging at the sentence level, and disorienting as the story moves between characters, deep into their minds, their pasts, into their homes, class distinctions usually unspoken, but ever-defining. It’s a deep dive into a dark sea, and beautifully spellbinding.

July 29, 2025

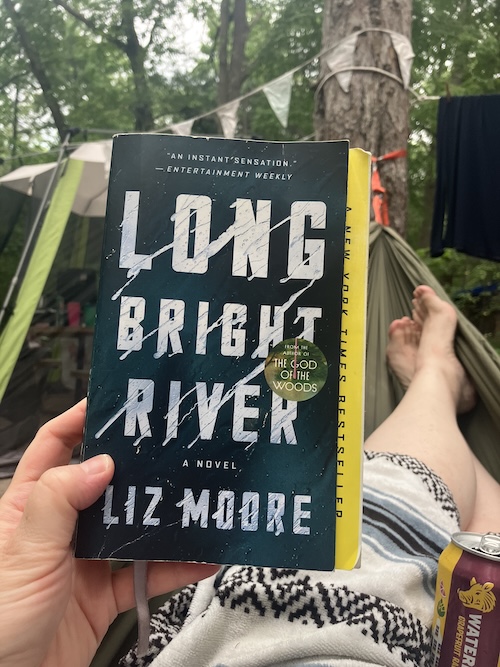

Summer Goodness

Last weekend we went away again, and I brought along Liz Moore’s 2020 novel LONG BRIGHT RIVER on a camping trip out of nostalgia for the weekend I spent last summer utterly absorbed in Moore’s GOD OF THE WOODS at the same park, and it was no surprise just how much it delivered because my husband and teen had already read the book before me and both of them loved it. And I did too (I’ve heard it said that it might be better than GOD OF THE WOODS, which I think is true, although GOD… subverted my expectations in the most interesting ways and this novel was a little more conventional). It’s the story of Mickey a police officer in Philadelphia’s gritty Kensington neighbourhood who lives in fear of one day coming upon the body of her sister, Kacey, a longtime addict, on one of her patrols, and for whom the line between her professional and personal lives become blurred when it appears that a serial killer is targeting vulnerable women in the neighbourhood. It’s a gripping mystery with all kinds of twists, but also a searing indictment of police corruption and incredible human cost of current drug crises, including opioid addiction and drug poisonings.