November 5, 2024

LIES I TOLD MY SISTER and WHO WILL BURY YOU?

Lies I Told My Sister, by Louise Ells

Louise Ells has become a friend since we “met” in 2019, after I read her story collection NOTES TOWARDS RECOVERY, and so it’s a real delight to be able to pick up her new book, the novel LIES I TOLD MY SISTER. The entire novel takes place over the night protagonist Lily spends with her younger sister Rose in a hospital emergency room after Rose’s husband is in a catastrophic car accident, the hours and the tension finally bringing to the surface years of secrets, resentments, and unspoken things.

The novel moves between the current moment in the ER in 2014 and incidents from the past—a traumatic loss from Lily’s childhood, a difficult marriage with painful struggles with pregnancy loss and infertility, Lily’s years living abroad when her husband was posted overseas, and the years the sisters lived much closer but were still worlds apart, each with secrets and pain in her life that the other would never know about. Until that night in the hospital, when the words are finally spoken.

It’s a tricky narrative set-up (how can one night contain an entire lifetime?) with so much of the novel told in flashbacks, but it works, mostly because Ells chooses to make the real journey Lily’s internal one as she finally faces her own reality, including the painful fact of her beloved second husband’s young-onset dementia. There’s a lot of love and forgiveness in this very moving story, and I enjoyed it all so much.

*

Who Will Bury You, by Chido Muchemwa

“Who will bury you?” demands Timo’s mother, the question woven throughout the story “This Will Break Your Mother’s Heart,” Timo “a late leaver, a decade behind all my friends who left straight after high school for the US, the UK, Australia, anywhere they’d have a better chance of thriving.” The story focusses on the distance between Zimbabwean Timo’s experiences in Toronto, the beginning of her first same-sex relationship, and Timo’s mother’s expectations of her daughter, conveyed mostly through stories of women at her church. “Don’t you think it’s time you started thinking about marriage, Timo? If you wait too long, who will bury you?”

Although Timo’s mother is also asking, “Who will bury ME?” With a child so far away, and the collection shows readers both sides of this exile, Zimbabweans far from home as their parents die or become lost to them in other ways. The collection begins with Timo and her mother, centred in Toronto, and then takes its reader back home to Zimbabwe, to other characters who are leaving their homes or preparing to leave, and characters who are left behind—in “Paradise,” Wiki maintains his family’s graves at the Paradise Cemetary.

In “The Snore Monitor,” Hamu finds work in a delicate job in Johannesburg. The next three stories are fascinating and involve the lore and history of the Kariba Dam, a major project from colonial Rhodesia. “Rugare” is the story of a boy whose big dreams don’t get him as far as he wants to go in Harare. And finally, “The Last of the Boys,” set in a Rhodesia beset by civil war and impossible choices as Zimbabweans waited on her verge of independence, as story especially resonant in such a moment of global strife and warfare. These are stories most specific, but universal at the very same time.

October 31, 2024

Two Ace Picks for Halloween

On Saturday I read FOR EIGHT STRAIGHT HOURS as part of the Turning the Page on Cancer readathon, helping to raise a total of more than $66,000 (and counting!) for Rethink, improving outcomes so that women with metastatic breast cancer can live longer and better lives. And the readathon’s proximity to Halloween meant that, once again, I chose a couple of books with a seasonal theme, two books with basically nothing in common otherwise, except that they were both so good.

I read Suzy Krause for the first time this year with her latest novel, I THINK WE’VE BEEN HERE BEFORE, and decided to delve into her backlist when she posted that her second book, SORRY I MISSED YOU, is about a (possibly) haunted house, ghostings, and maybe even actual ghosts, and therefore the perfect Halloween reading for those who don’t REALLY want to be all that scared. Which it was, exactly, and the scariest parts of the story really were the characters’ grief and loneliness, but offset by the warmest, sweetest story of unlikely connection and community. SORRY I MISSED YOU is about three women who move into a triplex, each of whom imagines she is the intended recipient when a strange letter turns up in the mailbox, and that the sender is someone particularly from her past. Twisty and terrifically funny, this one reminded me of a Claire Pooley novel, and gorgeously underlined Krause’s amazing literary talent.

And then I picked up THAT NIGHT IN THE LIBRARY, by Eva Jurczyk, whose debut novel I loved, and who just landed a very sweet deal for new thriller 11TH ARRONDISSEMENT. THAT NIGHT… is her second book, a locked room mystery set in the depths of a library sub-basement as a group of students endeavour to reenact the Greek ritual of the Eleusinian Mysteries, but things go wrong soon after the students are locked in when one of them ends up dead, and then they’re all going down, one after the other, none of them knowing who among them—if anyone!—can be trusted…until the very end. This one is dark and twisted, really gory, and sprinkled with such delicious humour, perfect for fans of THE SECRET HISTORY (and I actually liked it better!).

October 29, 2024

300 Mason Jars, by Joanne Thomson

It’s curious that 300 Mason Jars is such a personal book, inspired by the author’s history, because it also feels like a book that was created just for me, the cosmos in a jar on the cover as familiar as the one on my kitchen table, but it’s the ordinariness of this image, and of the other quotidian objects preserved in the paintings on its pages—crochet hooks, sugar tongs, a pair of scissors, a yellow pencil, along with many plants and flowers—that has this effect. Joanne Thomson is telling her own family’s story through her series of paintings of objects in Mason jars, a riff on preservation that had me thinking about Mary Pratt’s own paintings of jars and scenes of domesticity, but this images will have viewers/readers recalling their own histories, whether their own families were Canadian settlers in the 20th century, as Thomson’s are, or if their stories are different and there would be other objects on display in their jars. There is a sense of play and whimsy to this project—”Mason jar with pliers”; each painting is accompanied by a short piece of verse—but also a real gravity to it, the project inspired by painful parts of her family’s story that Thomson’s ancestors didn’t talk about it, but she brings it to the light of day, light being the very point (Mary Pratt again!) and she imbues it all with such beauty. This book deserves a special spot on Canadian coffee tables, to be flipped through, and returned to, time and time again.

October 21, 2024

Death of Persephone, by Yvonne Blomer

I walked home reading this book on Saturday evening, the setting sun turning the tall buildings east of us golden, and it felt like the book was casting a spell. I was a woman walking in the city reading a book about women walking in the city, a riff on the myth of Persephone told through poetry structured as a detective story, and this book was doing it all, the plot, the language, the allusions, the truth of it. Blomer’s Persephone in Death of Persephone is Stephanie, a young woman who’s grown up in the tunnels beneath Montreal where her Uncle H. runs a souvlaki stand, her story punctuated by case notes from Detective Inspector Boca, investigating a series of violent deaths by young women throughout the city. Each poem taken on its own is a marvel, colours ever-changing when it’s held up to the light, but they come together to take on the rhythm of a gripping crime novel, a fierce feminist tale and who dunnit is misogyny. From “Violence is a bone in the body”: metatarsal, metacarpal, maxilla,/ mandible. How violence bites.”

October 18, 2024

The Rich People Have Gone Away, by Regina Porter

I had no idea what I was getting into when I started reading THE RICH PEOPLE HAVE GONE AWAY, a Covid-era novel by Regina Porter, a book that came to my attention via Maris Kreizman’s wonderful substack. A novel whose first section begins with an encyclopedia definition of “door”: “barrier of wood, stone, metal, glass, paper, leaves, or a combination of materials, installed to swing, fold, slide, or roll in order to close an opening to a room or building,” the novel’s following two sections beginning with similar definitions of “doorframe” and “threshold.” And Porter’s doorway/opening to the novel itself, (which is to say, her book’s first paragraph): “Mr. Harper takes sex in doorways. Halts new lovers at the threshold of his front door. Left hand on shoulder. Right hand on hip. He searches the ninth-floor hallway for furtive eyes before pressing the whole of himself in the tender nook of his lover’s ass.” I mean, what now?

Nothing is what it seems in THE RICH PEOPLE HAVE GONE AWAY, set in March 2020 as the world has shut down, neither Mr. Harper himself, who is Theo, presumed suspicious when his young pregnant (white) wife Darla (a bassoonist) disappears on a hike near their cottage in upstate New York, nor the teen in the Cardi B t-shirt who seems to be loitering in Theo’s Park Slope building, nor Darla herself with her secret skills in hotwiring vehicles, or her father, who perished on 9/11. Porter is also an award-winning playwright, and the novel’s playful heteroglossia has those skills on display, resulting in a dynamic and shapeshifting text, full of tricks but never cheap ones, missing white lady/GONE GIRL tropes turned inside out and on their noses, and it’s all so interesting. The narrative moving swiftly through that strange and harrowing season (the teen in the Cardi B shirt’s mother is hospitalized with Covid; she comes off her ventilator; she goes back on her ventilator…) to late spring, late May, the teen boy’s phone blowing up, Minneaopolis, another threshold. “Did you see it?” No resolution. A story without end, but that is also what makes the novel particularly satisfying.

October 16, 2024

Keep, by Jenny Haysom

I’ve been reading all over the place lately, out of necessity, sometimes seven books at at time, bits and pieces, and so it was quite delightful to fall into a novel for the first time in a long time, to read the whole thing in a day. I loved KEEP, by Jenny Haysom, a novel following her award-winning debut poetry collection DIVIDING THE WAYSIDE. KEEP is the story of two real estate stagers charged with packing up the life of Harriet, an elderly poet with dementia, who become entangled in the mess of her life. Although their own lives are not so tidy either—Jacob, in his early 20s, has just been dumped by the boyfriend he moved to Ottawa to be with, having tried and failed to conjure domestic bliss for them; Eleanor, 20-some years older, is dissatisfied with her own domestic arrangement, the small home she shares with her husband and three children altogether too confining, everybody relying on her labour to make it work, and she’s exhausting. KEEP is a novel about building home, about keeping house, about what life does to everybody’s best intentions, and the distance between the faces we present to the world and the realities we’re actually facing. The braided narrative is so well balanced, each character a vivid and engaging presence in the novel, and it’s interesting (and refreshing!) to encounter a book presenting three different generations together and the genuine connections between them.

October 16, 2024

BOOKSPO Season Two

7/10 episodes of the BOOKSPO podcast are up now (with more to come on the next three Wednesdays). I’m also so pleased to report that the podcast is now available on Spotify, along with Apple Podcasts, Substack, and (pretty much) everywhere else you get your podcasts.

Guests so far are Corinna Chong, author of the Giller-longlisted BAD LAND; Ayelet Tsbari, author of SONGS FOR THE BROKENHEARTED; Alice Zorn, author of COLORS IN HER HANDS; Marissa Stapley, author of THE LIGHTNING BOTTLES; Suzy Krause, author of I THINK WE’VE BEEN HERE BEFORE; Jennifer Whiteford, author of MAKE ME A MIXTAPE; and Anne Hawk, author of THE PAGES OF THE SEA. More to come!

October 15, 2024

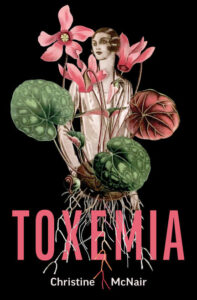

Toxemia, by Chistine McNair

TOXEMIA‘s gorgeous cover (a collage by @rhinocerospoems) sets the reader up for what’s to come, the literary bricolage, a hybrid of memoir and poetry. “To Lady Sybil,” the book is dedicated, the character from DOWNTOWN ABBEY who died of pre-eclampsia in the show’s third season (after which I refused to watch any more because *how could they have done that?!*). Christine McNair blends high and low cultures, arts and science, words and images, memoir and research to tell the story of her life as a woman with a body, a body that is so often wrong or dangerous, her symptoms and experience disbelieved, disregarded. McNair’s experiences of pre-eclampsia during her two pregnancies don’t just have consequences for her mental and physical health in the years afterwards, but also tap into her experiences with depression, self-harm, and eating disorders. “I am now more afraid of telling doctors my history,” she writes. Though with TOXEMIA, she’s made art of that story, a moving and compelling narrative, strange and edgy, unsettling. Unputdownable.

October 10, 2024

The Accomplice, by Curtis “50 Cent” Jackson

I will admit that I first picked up 50 Cent’s debut novel because I found the idea of a novel by 50 Cent really funny, but when I opened up THE ACCOMPLICE, I was surprised from the very first line: “Nia Adams doesn’t have a green thumb, but waters her garden diligently, cares for the soil, tends to the flowers, and tames the weeds. Her favourite perennial is the Lupinus texensis, the Texas blue bonnet. The bright blue petals are the showpiece of her front yard. The flowers thrive on full sunlight and damp soil and are resilient during dry spells. Like Nia, they’re survivors.”

With delight, I can tell you that I loved this book, the story of Nia Adams, the first Black female Texas Ranger, whose fate becomes bound up with that of Vietnam-vet turned thief Desmond Bell after a bank robbery goes very strange with nothing of value appearing to be stolen. The lines between good guy and bad guy, and right and wrong, becomes blurred as we learn more about Bell’s story and as Adams comes to understand her colleagues and the institution she works for.

Written in partnership with crime novelist Aaron Philip Clark, THE ACCOMPLICE is a deft thriller with proper twists and turns, and is absolutely gripping. The only thing that tripped me up was some fairly gruesome violence in a couple of parts, but thankfully the story doesn’t linger there, instead tackling big questions about history, race, power and the possibility of redemption. And 50 Cent even makes a cameo in the text, or at least his music does, when “P.I.M.P.” is being played on somebody’s karaoke machine—Desmond Bell unplugs it.

It’s all a little ridiculous, but I’d be disappointed if it wasn’t.

October 8, 2024

The Lodgers, by Holly Pester

“If you’re unsettled, you’re unsettling,” the narrator tells us in THE LODGERS, the debut novel by UK poet Holly Pester (and also the debut novel published by Assembly Press here in Canada). It was a novel I wanted to like based on its premise (a woman returns to her hometown to live in a sublet, all the while reflecting on the person who’s moved into her just-vacated previous quarters) and also based on its cover design (“For some reason I ate [the sandwich], I wasn’t happy. But as a result the triangular box was empty, with an inside that resembled, like sarcasm, the one I was in. I looked inside. It had a window too.”) but very styled slightly abstract fiction that refuses to show its hand isn’t always my favourite thing (so many cool books I tried to love, but couldn’t) so I wasn’t sure how THE LODGERS might go over. It isn’t that I don’t like being unsettled per se, but instead that I want my novels to add up to something, being cool is not enough, but this one does add up. Strange, disorientating, and indeed unsettling, but it has a hook for me to hang my hat, metaphorically speaking. Our unnamed narrator’s new sublet is around the corner from the home of her mother, Moffa, a home to which the narrator still has a backdoor key, letting herself in from time to time once she’s back in town, but Moffa is never there. And neither is Kav, the supposed inhabitant of the second bedroom in her sublet, whose arrival could come at any time, the narrator never able to relax into her new abode because of this anticipation. And meanwhile she addresses the new inhabitant of the room she’d left behind, a room that was only ever hers between the hours of 6pm and 9am because otherwise her landlady operating her massage business of the space, and the narrator found comfort in belonging to this home, however tangentially, and her connection to the landlady’s child, the suggestion of a stable domestic situation that our narrator herself has never known. This is a novel that goes in circles, the way the narrator’s life seems to be, every path leading back again to a home that never was, poignant, comic, and biting at once.