October 17, 2022

Nine Dash Line, by Emily Saso

The most fascinating, original, well crafted novel I’ve read in a long time is Nine Dash Line, by Emily Saso, a novel whose premise—I will admit—didn’t grab me immediately, because it’s about a guy who’s stranded alone on an atoll in the South China sea, exiled by the Chinese communist government. All the things I tend to like best about novels are impossible in novels about people stranded in the middle of the sea—family drama, elaborate dinner scenes, bookshop settings, etc.—even if the guy on a atoll shares parallel chapters with a female US Navy officer who—for reasons as convoluted as the first character’s exile—has found herself marooned in an inflatable life boat, the sea around her rife with sharks and mines, about to wash up aboard a rusted out vessel belonging to the Philippines.

So how is this author going to pull this one off, you might ask?

To which I’ll reply with one single word: MASTERFULLY.

The book itself, it grabbed me at once, because oh my gosh, this is such a good one, built on the kind of premise that has to be pitch perfect to work at all, but it really is. By the end of the first chapter, I was absolutely hooked, riveted, Saso’s plotting and prose casting an incredible spell that held to the final page, resulting in such a strange and expansive novel, a story of geopolitics, about espionage, war, and ideology, and pain, and longing, and the necessity of living by one’s wits to survive impossible situations, about the impossible becoming possible, for better and for worse.

I’ve got no THIS BOOK MEETS THAT BOOK comparison here, because I’ve never read another quite like this one, a book so deftly imagined that I’m in awe of Saso’s talent, mind-blown by the creative skills required to even begin to imagine a book like this, let alone the technique required to execute it.

All I can tell you is that you’ve got to read it.

October 14, 2022

Finding Edward, by Sheila Murray

After hearing great things about Sheila Murray’s novel Finding Edward, I finally picked it up last weekend to discover it lives up to the praise of critics like Donna Bailey Nurse (who’s written, “This beautiful necessary novel will become a touchstone.”)

And then this week, it was nominated for the Governor General’s Literary Award!

Though it took a bit of time for all its pieces to come together for me, a book that starts off kind of quiet, which is fitting seeing as its protagonist, Cyril, is quiet, understated, someone you might not even notice if you passed him on the street.

Cyril, just 21, raised by his mother in Jamaica after his white English father leaves their family, is left alone after his mother dies, but he has an inheritance from a benefactor, his mother’s former employer, who’d encouraged him to pursue an education, and Cyril decides to finally take this advice and travels to Canada to enroll at then-Ryerson University (the novel is set in 2012), but being in Canada, and being Black in Canada, turns out to be far more complicated and fraught than he’d expected. His understanding of situation is deepened after he finds photographs and documents from the 1920s pertaining to a mixed race child called Edward, and begins archival research to determine Edward’s identity, thereby weaving in key (and under-celebrated) elements of Canadian Black history including Thornton Blackburn, who started Toronto’s first taxi company in the 1850s; Mary-Ann Shadd, the first Black newspaper publisher in Canada; the story of Nova Scotia’s Africville community; the experiences of Black railway porters (which is also portrayed in the Giller-nominated novel The Sleeping Car Porter, by Suzette Mayr); and more.

At the same time, Cyril’s violent encounters with police and precarious situation with work, housing, school and finances (he’s helping to support his two siblings back in Jamaica) are reflective how little has changed over the years, all this bringing him into contact with local Black activists who help him to imagine possibilities for a different kind of Black future.

Just a satisfying literary experience, plus a rich portrayal of Black experience in Toronto and beyond.

October 6, 2022

Shrines of Gaiety, by Kate Atkinson

In Shrines of Gaiety, Kate Atkinson’s thirteenth book—which is truly an amalgam of her divergent literary preoccupations over the last twenty five years—there are secret exits, disorienting corridors, narrow staircases, and a bar that swings out of sight at the push of a button, and so too are there tricks in her prose, although they’re not cheap ones, and the prose itself is truly luminous (and also had me reaching for my dictionary several times—”testudinal”…who knew?).

Like all of Atkinson’s books, this one plays tricks with time—albeit less overtly than Life After Life, just say—the entire book taking place over the course of a few weeks, but its chronology including small jumps back in time to show readers what we think we already know from a different angle—and perhaps also suggesting that moving forward in time in 1926 was an uneasy prospect, the traumas of WW1 still unbearably present, no matter how nobody wanted to talk about it.

The novel opens with the release from prison of Nellie Coker, the notorious owner of several clubs in London’s Soho district, who’d been put away for a few months for her defiance of licensing laws. She’s the mother of two sons and a handful of daughters, plus the possessor of shady origins and dealings just as dodgy, which is why John Frobisher is on her tail, a police inspector relocated to the local precinct to look into corruption and possible alliances between Nellie and the force.

On top of that, women’s bodies keep turning up, and it’s two missing girls who’ve brought Gwendolen Kelling from York, a librarian who’s recently experienced her own change of fortune and who has volunteered to come to the city to seek her friend’s runaway half-sister and her companion, two young teens starry-eyed and looking for fame on the London stage and who are therefore ripe for exploitation…

It’s a seedy underbelly for a world that, on its surface, is so sparkling and fun, and it’s this juxtaposition that Atkinson explores, as well as the cheapness of that shiny veneer and what lies beneath it, which is trauma, addiction, violence, and longing. An exploration that feels quite resonant a century after the story is set—as well as ominous, because 1926 would be as good as it got for a very long time.

John Frobisher is no Jackson Brodie, and it becomes clear that Atkinson is not launching a detective fiction series here, the novel remarkably self-contained, all its ends tied up neatly—though perhaps with a bit too much fizzle after more than three hundred pages of sizzle. (So what, is the question I expect my favourite critic Rohan Maitzen will be asking, and I can’t wait to read her review, because I’m always just dazzled by Atkinson, while Maitzen holds her to the rigorous literary standard I think her work deserves…)

In the four days since I finished reading Shrines of Gaiety, however, the story has very much stayed on my mind, suggesting the novel is not mere frippery, but instead a work of literature that—like the best of Atkinson’s works—asks vital questions about the terrible sublimity of human experience and the real meaning of the stories we tell.

September 29, 2022

Woman, Watching, by Merilyn Simonds

I LOVED this book! Louise de Kiriline Lawrence is the most fascinating woman I’d never heard of, born to Swedish aristocracy, goddaughter of the Queen of Denmark, trained as a Red Cross nurse in WW1, which is how she met her Russian husband, whom she followed into a post-revolutionary Soviet Union beset by civil war, and then he was eventually killed by the Bolsheviks, and in the aftermath of that loss, she emigrates to Canada to begin nursing in Northern Ontario, where she becomes the nurse to the Dionne Quintuplets during their first year of life…all this taking up just 64 pages in a book that runs for 300 more.

Because after those extraordinary formative experiences, according to Merilyn Simonds in biography Woman, Watching: Louise de Kiriline Lawrence and the Songbirds of Pimisi Bay, is where the real story begins, Lawrence buying a rural property where she builds a log cabin (without plumbing or electricity) and becoming one of the foremost ornithologists of her time, thanks to her own powers of observation and correspondence with other bird experts who informed her ideas. She’s able to note effects of habitat loss and other human interference before Rachel Carson became well known or celebrated, build support and information networks with other women birders, and write six books, many articles and magazine stories, and a foundational monograph on woodpeckers.

Born into affluence, Lawrence’s early years of hardship would have primed her to be resourceful and grateful for small pleasures, but even still, her strength and stoicism were remarkable—there is a part where she ventures into the bush to find moss with which to insulate her windows for her unheated cabin, and then she falls and dislocates her shoulder, but (as she reports cheerfully to her correspondent—she was also a prolific letter writer, fortunately for her biographer!) she was able to push the joint back into place AND ended up getting some of the best moss she’d ever gathered.

In some ways, this story of Lawrence’s cabin near North Bay reminded me of Virginia Lee Burton’s The Little House, with the city ever encroaching, growing closer. It’s also a story of the North American Conservation movement (some parts of this mapping beautifully with Michelle Nijhuis’s Beloved Beasts, another book I loved), of discrimination against women in science, of changes to science so that amateur observers have less to contribute, of the struggles in the career of a writer, and the perils of growing old, but most of all, it’s a story about birds, and what we might see if pay attention to the world around us, of the wonders and miracles of the natural world.

September 26, 2022

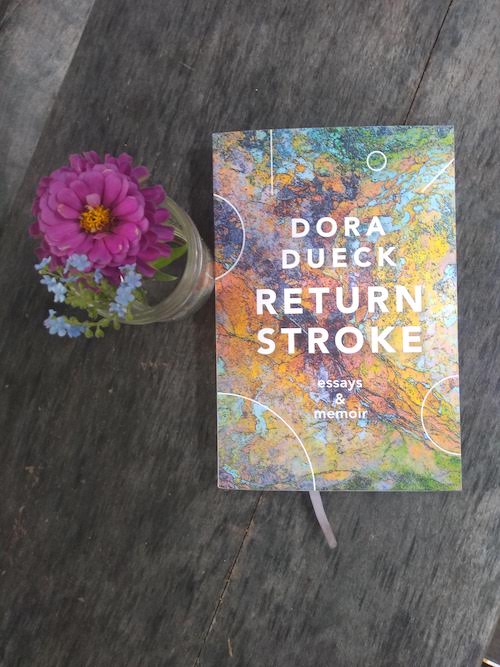

Return Stroke, by Dora Dueck

In 2019, I founded a pretty sweet boutique bookselling operation called BRINY BOOKS, and Dora Dueck’s most recent novel, ALL THAT BELONGS, was part of our second lineup of titles, a novel I loved, just as I’d loved her previous book, the story collection WHAT YOU GET AT HOME, and I’ve also enjoyed her nonfiction over the years, at her blog and in literary journals, and so I’ve been looking forward to her most recent release, RETURN STROKE: ESSAYS AND MEMOIR, published by Canadian Mennonite University Press, and it’s everything I was hoping it would be. Dueck reflecting back from her 70s on her girlhood growing up in Alberta, her marriage and years of intensive motherhood, which included a stint living in her husband’s native Paraguay, and all the wonder and culture shock that experience entailed, and then her own evolving thinking about feminism, and faith, and her relationship to her church after her daughter comes out as queer, and she writes about getting older, the lightness of aging, and the heaviness too in an essay about the final days before her husband’s death, a gorgeous evocation. This is a book that brought me to tears more than once or twice.

What I love so much about Dueck’s writing and her thinking is that nothing is fixed, and she is eternally curious, taking notes and learning, about the past and the presence, much of her work concerned with memory and history, but in such a vital, living way, not as an affirmation but a process of discovery. The first half of the book is a series of essays, and the second (roughly the same length) is a work of memoir about her time in Paraguay in the early 1980s, and she writes about the revelation, as she returns to the letters and diaries that are her primary sources, “I’d been thirty-two…, which was, I suddenly noted, the current age of our youngest child, and that child seemed—well, young!” An entire page about how relative are the ideas of old and young—which was a mirror image to the revelations of Emma Straub’s protagonist in her latest novel This Time Tomorrow—and then this beautiful paragraph:

“That I was young is the truth, and yet, in the memoir-writing-effort of existing out of time, my youthfulness at thirties-young seemed an invention. And having coaxed this fiction/truth into text, I found myself suddenly standing next to my thirty-something children and in the flashes—swift and jaggedly stunning as lightning strokes—of knowing myself then and my children now, we seemed to meet as age-equals. As if we’d bumped into each other on some magnificent high bridge. The meeting amazed me, made me dizzy too. I was proud of these children, of who they were at the moment, and it pleased me more than I can express that the Me of the Chaco could, in this moment of meeting, be compared to them.”

Though I’m pretty sure the pleasure is entirely mutual, seeing what a privilege and a most illuminating delight it is to bump into Dueck in these pages.

September 13, 2022

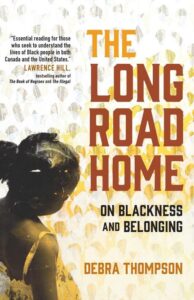

The Long Road Home: On Blackness and Belonging, by Debra Thompson

Debra Thompson’s The Long Road Home: On Blackness and Belonging is an excellent and bracing work of memoir and social science, providing a Canadian lens on topics explored in the works of Isabel Wilkerson and Ta-Nehisi Coates. Thompson writes about being a Black Canadian and her relationship to America, the land from which her once enslaved ancestors had escaped for Canada, which makes it a curious kind of homeland. And then about what kind of “escape” Canada offered after all, Canada’s own legacy of enslavement and racism seemingly muted in contrast to its southern neighbours, but that legacy lives. Growing up in Oshawa, ON, during the 1980s, Thompson was so often the only Black person, “[which] didn’t make me feel particularly unique or successful or special. It made me think that there was something inherently wrong with Black people and that I had to fight against it every day to defy what the fates had in store for us.”

After completing her doctorate (with experiences in academia rife with anti-Black racism), Thompson arrives at Harvard on a post-doctoral fellowship in 2010, just as the hopefulness of America’s first Black president was beginning to crest, and the story of her decade to follow traces a powerful trajectory in American history and politics, particularly in regards to race. She writes of her own ambivalence towards notions of American democracy, an ideal that has forever failed to live up to its potential and was imagined for the white men who have long been its beneficiaries, a process in which “African Americans are perpetual losers.” Her connection to American is further complicated as she moves on to teach in a town in rural Ohio, then in Chicago, and finally Oregon, as American moves from Obama to the election of Donald Trump, and then the “reckoning” of Black Lives Matter throughout the entire decade and public demonstrations following the murder of George Floyd in 2020. (She wonders if racial justice, for many white liberals, wasn’t just another Covid hobby to cut through the boredom, up there with Tiger King and sourdough.)

n 2020, Thompson moves—with her American partner and their children—back to Canada, to Montreal, which offers a whole additional layer of complexity to her lens, as she takes on notions of Blackness in the very specific context of Quebec. And throughout all of this she’s mindful of her place on Indigenous lands, with teachings by Indigenous scholars such as Eve Tuck and Leanne Betasamoske Simpson underlining her approaches to political science and being a human in the world.

The Long Road Home is a sparkling and engaging work, and also a demanding one, for white readers. Not that it’s difficult to read (see previous sentence on “sparkling and engaging”; I read it in two days) but that it’s literally demanding something of us, white readers—our discomfort, our willingness to see the white supremacy inherent in our systems, to wake up to the realities of racial injustice and begin to imagine a better, fairer world.

September 9, 2022

Blue Portugal, by Theresa Kishkan

To those of us who’ve been following Theresa Kishkan on her blog for many years, the preoccupations of her latest book, the collection Blue Portugal & Other Essays, will be familiar, the quilts, the homesteads, the memories, the blue. But it’s the stunning craftsmanship of the book, the fascinating threads that weave the pieces together and also recur throughout the text, that make this book such a pleasure to discover. How quilting squares are analogous to the rectangles from which, one by one, Kishkan and her husband literally constructed their home on BC’s Sechelt Peninsula, and the blueprints, and the blues of dye, and of veins, and of rivers, and of how one thing turns into another—how? How does a body get old? How do children grow? How does a family tree sprout so many new branches? And from where did it all begin, Kishkan going back to seek her parents’ nebulous roots in the Czech Republic and Ukraine, in a 1917 map of lots in Drumheller, AB, in everything that was lost in the Spanish Flu, and how we’re connected to everything our ancestors lived through.

Kishkan, as she tells us in her preface, came to writing via poetry, which she put aside when her children arrived, and when she picked up her pen again, she wasn’t a poet any longer: “I had the impulse to write, I had ideas to explore, material accumulating in my mind as my quilting basket accumulated scraps of cotton, but I didn’t have a shape for my thinking any longer. The lines I wrote continued past the point where a poet would consider the stanza, the lyric, complete. At first I tried to wrangle them, contain them, but one day I just let those lines continue, as prose maintaining a certain rhythm but given the freedom of the wide space on a page, One line led to another, then another. Their purpose was not to create fiction but instead to make a map of my own reflections, main roads and secondary roads, river systems, mountains, an beautiful circled stars for settlements. One line led to another, a threads leading me into the heart of meaning I hoped would be there, a little knot at the centre.”

And the meaning is there, but the poetry is too, still, (but not still!), this book a heartful, artful offering.

September 2, 2022

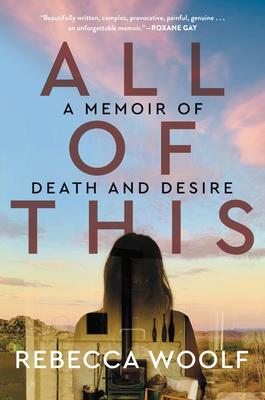

All of This, by Rebecca Woolf

Rebecca Woolf (formerly of Girls Gone Child) is the only blogger on the planet whose sponsored posts I could actually stomach.

She once wrote a post sponsored by an almond company, and I still remember it.

So it’s not exactly shocking that her beautiful, gutting, raw, and awesome memoir, All of This, has proved to be unputdownable, a brave and visceral story of marriage, death, and widowhood from someone who has made a career out of making the unvarnished truth shine.

As a long-time reader of Woolf’s blog and instagram, I was wholly invested in her family life, in her marriage, and the story of her husband’s painful death from pancreatic cancer. And because part of that investment involved my admiration of her ability to hold two truths at once—that, say, her own decision to proceed with an accidental pregnancy at age 23, and her staunchly pro-abortion feminist politics are not incongruous—that the story of her family life, marriage and Hal’s death turned out to be far more complicated and tumultuous than it appeared from the outside only seems to be only adding texture to the story we’d been reading all along.

I remember the rats in the walls. I remember her commitment to telling the story until it came true. I know how hard she tried.

And I’m awed by her capacity for truth telling, and growth, and learning in public.

What does it mean when your husband dies and you feel relief? To be a widow who wants to fuck? To be a mother of four children who’ve just lost their father, and also a mother to one’s own self, one’s own soul? Beginnings and ends all at once. Everything is a circle.

Extraordinary writing, candour, courage and generosity is on display in this beautiful memoir, and also so much raw and bloody love.

August 30, 2022

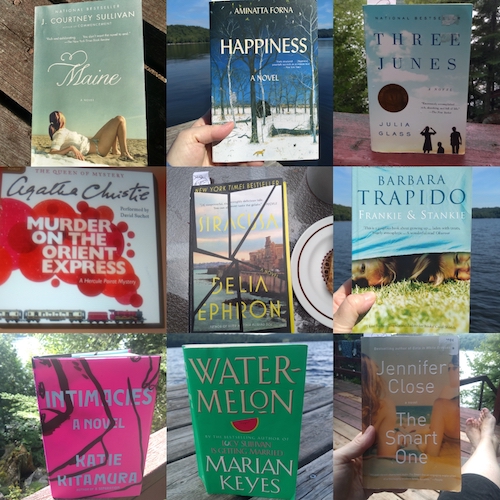

More Vacation Reads

For the second summer in a row, we’ve gotten away for two one-week-holidays at a cottage, and I feel so lucky that this is possible for us and will go out of my way (if necessary) to continue to make it so because it’s just the very best thing, so relaxing and restorative, which has been the theme of my summer in general, and what a gift. And not just because I got nine whole books read!

The first was The Smart One, by Jennifer Close, which I stole from the resort library of the cottage we stayed at in July (though I left two books in its place, so that’s okay, right?). Since reading Marrying the Ketchups in July, I’ve been wanting to launch a Jennifer Close kick, because I enjoyed it so much. The Smart One, her second novel, is similarly a book about adult children coming home again after failures to launch, and it started out fine enough, very typical commercial fiction fare, I thought, but then I started to notice the thread of thoughtfulness that wound the different parts of this story together, and the questions the book asked about what it means to be “the smart one” or “the pretty one,” and the impossibility of any woman making the right choices. Surprise pregnancies, Catholic guilt, people called Cla(i)re and the ties that bind were introduced in this novel, themes that would appear in subsequent books I read.

In Watermelon, by Marian Keyes, the pregnancy is not, in fact, a surprise, but what is a surprise is that Clare’s husband announces he’s leaving her right after their child is born. (He didn’t want to mention it before, because it might have been a risk to her health then.) And so Clare decides to pack up her London life and head home to Dublin, to the house that she grew up in with her legion of sisters, and there she proceeds to drink away her pain and then plot her way toward a better life, so that when her husband finally appears to win her back he’s not really sure what’s happened. I will confess that this is not the best Marian Keyes book I’ve ever read—and I found it in a Little Free Library anyway, so no matter. It was entertaining enough but also utterly implausible—Clare’s newborn baby seems remarkably independent and leaves her mother with plenty of time and space to explore her own needs, which was certainly not my postpartum experience. I also found it very amusing when everyone in this book from 1996 worries that their bum looks big from the vantage point of the 2020s when big bums are all the rage and unflattering jeans are where it’s at. This book was something of a relic but also a perfect diversion for a summer’s day.

Next I read Intimacies, by Katie Kitamura, which was the odd man out of these books in many ways (such as, I didn’t find in a Little Free Library), but had more in common with Marian Keyes’ Watermelon than you might imagine (and intersected with Aminatta Forna’s Happiness in interesting ways). It’s true that this is not a novel about ties that bind, instead it’s about being free of those ties, which doesn’t always feel like freedom. Intimacies is a novel about exile, about belonging nowhere, and features a protagonist who’s dating a man whose wife has left their family, inviting some of the parallels to the Keyes. It’s a curious and alienating novel, one just a little too cold and precise for my liking, but that’s not a criticism, just taste.

After that I read Siracusa, by Delia Ephron, who I’ve never read before, and I think I found this book as a secondhand bookshop. It’s a novel, like Intimacies, with an atmosphere that feels oppressive, but far more revealing, and actually intimate. Could be described as a taut thriller, but it’s weirder than that, about two couples who travel to Italy together and whose lives seemingly unravel on the journey with players being played and too many secrets threatening to be revealed. Quick and eerie, I really liked it.

And remained by the Ionian Sea for my next book (or at least it’s beginning), Julia Glass’s Three Junes, which I knew nothing about, except that it won the National Book Award in 2002, and my friend Marissa recommended it to me (and she never steers me wrong). I loved this book, which comprises three distinct sections—the first of Scottish widower Paul on a Greek holiday months after the death of his wife; the second from the perspective of Paul’s son Fenno, a NYC bookseller coming home to Scotland after the death of his father five years later; and the third set five years after that when a character we glimpse in the first section meets Fenno on Long Island where she is accidentally pregnant (and there’s a pro-life activist; curiously, there is not an abortion in any of the books I read in this bunch, truly a holiday indeed) and waiting for her boyfriend to return home from Greece so she can tell him about the baby. This novel is a bit strange, and its connections aren’t always clear, but I found it utterly absorbing.

And then I read Frankie and Stankie, by Barbara Trapido, which blew my mind. I read Trapido’s reissued debut, Brother of the More Famous Jack, when we were in the UK in April, and while I enjoyed it, it was so unlike anything else I’ve read before that I had trouble placing it in my mind. This novel, written more than thirty years later, is helping me do so, however, because it’s brilliant. Ostensibly a coming of age novel set in South Africa during the 1950s and 1960s, it manages to be a fascinating (and hilarious) character study, story of a family, but also the most interesting history of South Africa I’ve ever read at once. (In her notes at the end of the book, Trapido explains that the forty years that she’s spent in the company of her husband, Stanley Trapido, a professor of South African history at Oxford, certainly informed her point of view.) I learned so much from this book, but it was also delightful, and now I am officially Barbara Trapido-obsessed.

All the while we were listening to Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express in the car on audiobook—it was so good!! We all kept coming up with reasons to go somewhere just so we could get in the car again and hear what happened next. Truly a delight for the whole family, even Stuart, who had watched the movie recently so had a good idea of what was coming.

And then I read Happiness, by Aminatta Forna, which I purchased at the Toni Morrison event I attended at Luminato in June, and like everything associated with that event, it was just so fantastic. As unfathomable as it seems, a novel about urban foxes in London, coyotes in the northeastern United States, and PTSD from war in Sierra Leone, amongst many other things, the novel becomes a study of wildness, of humanity, of love and goodness. Part of it also spoke directly about my own anxiety, my fear of hardship and suffering, a fear of trauma which is seemingly a condition of white, middle class, privileged people in the West, which might cause us to turn our backs on those for whom trauma is lived experience. And trauma also doesn’t have to be destiny—it changes one, but it doesn’t necessarily leave one damaged, as psychiatrist Attila explains. There’s so much to unpack here, but I’m looking forward to reading it again and getting to work.

And finally, Maine, by J. Courtney Sullivan, which I’d saved for the end, something light and easy, another seaside book with Catholics, accidental pregnancy and someone called Clare, though it was probably the most forgettable of the bunch, so I’ll leave it at that.

Hooray, hooray for holiday reading.

July 29, 2022

Summer Reading

I would say that time’s gotten away with me since my week in Muskoka earlier this month, but that’s not strictly true. In fact, time has very much been on my side these last two weeks, which means that I’ve not been very busy, had enough time to do the things I need to do, and haven’t pushed myself to accomplish very much extra, such as recapping my holiday reads. But I’m finally going to get it done right now, because the reading was just so excellent.

I started with a reread of Judy Blume’s Summer Sisters, which was published in 1998, and I don’t recall the circumstances under which I read it the first time, except that I think it was a book I enjoyed along with my mom and sister. And when I read it again, I was surprised to find out how much of it was still so familiar to me, even though I probably haven’t read it or even thought about it much in the last twenty years. Such a great summer book, rich and sweeping and just a little bit trashy. Holds up entirely, except for Vix’s reference to that Cherokee ancestor who’d gifted her those cheekbones, because we just don’t do that anymore. Lots of swimming in the pond on Martha’s Vineyard.

And next was Black Cake, by Charmaine Wilkerson, which I found absorbing, even if the storytelling style didn’t really work for me, skimming a (too) broad surface instead of plumbing depths. But it was still really fascinating, first with lots of ideas about food and colonialism and culinary history, and one of the characters is even an ocean scientist—there’s a whole lot going on. My favourite part, though, was the swimming, which I wasn’t expecting, because most Black characters in Caribbean-set books don’t get to swim so much, but swimming is a big part of the storyline here, as well as surfing, and I loved that.

And then I read Ghosted, by Jenn Ashworth, which I bought when we were in the UK because it was shortlisted for the Portico Prize for Northern English writing. I also bought her novel The Friday Gospels, and loved it, so expectations were high—and oh, she delivered. Ghosted is about a woman whose husband disappears, and she doesn’t tell anyone, which is kind of suspicious, plus she leads a pretty isolated life anyway and has a complicated relationship with her ailing father. There are secrets, but just like in Gospels, they’re not what you think they are, and Ashworth has such a gift for crafting suspense and writing sympathetic characters who are heartbreakingly human. No swimming, but scenes set in Morcambe and Brighton mean beaches definitely factor.

Following that, I read Tara Road, by Maeve Binchy, whose books I always dismissed with literary snobbishness, but I’ve come round, though hers is a curious kind of storytelling, very much telling. But what a wondrous tapestry of family and community Binchy weaves here, and I was utterly absorbed in this story which sweeps decades and continents, with women at the centre. Wasn’t expecting much swimming in this one, but there is a scene at the beach which inspired the opening scenes of James Joyce’s Ulysses!

Another Irish novel up next, Love and Summer, by William Trevor, the third novel I’ve read by him, and the least subversive, though it was in its own way, just more subtly so than the others (Miss Gomez and the Brethren and Death in Summer, both of which had evil lurking on its fringes and such wonderful dark humour). I think I love the works of William Trevor, and want to read them all. No swimming here, but there is a lake where Florian Kilderry walks his dog, and this is very much a novel about the pains of restraint and so nobody dives in.

I’ve already written about What Storm, What Thunder, by Myriam J.A. Chancy (SO GOOD!), which is definitely not a swimming novel. The one character who ventures into the sea ends up in a tsunami, so consider that a warning, but oh, what a book.

And finally, Every Summer After, by Carley Fortune, which is a much hyped book of the summer, perhaps too hyped for my liking, but I enjoyed it well enough, and its main character swims across the lake every summer, which is the kind of project I can get behind.