May 9, 2024

The Game of Giants, by Marion Douglas

I loved Marion Douglas’s novel The Game of Giants, though I’m not sure where to start in telling you about it. The back of the book describes the story as beginning with narrator Rose and her partner Lucy in the early 1980s discovering that their son Roger has developmental delays, his abilities marked the third percentile, which sends Rose back into her own history to explore when things went awry, which was early, because Rose as a character is pretty off-beat herself, and so is the narrative. But I’m not actually sure that this is what the story is “about” at all, and instead have a sense that this is a novel intent its own unique trajectory, intent on the propulsiveness and sharpness that results from Rose’s off-beats, and the terrific momentum created by her narrative voice and the remarkable ways that (in her experience) one thing leads to another, questionable choices culminating in a rich tapestry of experience, insecurities, lessons and longings. This novel is such an achingly hilarious story of tender humanity, with Munro-country vibes and the literary influence of Alberta, and yes, unconventional motherhood is where we finally arrive long after the runaway train has left the station on the wildest of rides, Rose struggling to accept the extraordinary reality of her son because she’s never been able to accept the reality of herself. But the reader does, just as Rose’s long-suffering partner Lucy does, Rose Drury a literary creation to fall in love with, made up of foibles, heartaches and broken parts like nobody else is, just like everybody else is.

May 7, 2024

Stories from the Tenants Downstairs, by Sidik Fofana

“But what’s sad in this whole thing is Wild One ain’t the criminal here. No, no, no. He jus a dude who did suttin. The criminals is us people around him, the people watching someone shake someone else awake from a dream and not doin nothin to stop it.” —”The Young Entrepreneurs of Miss Bristol’s Front Porch.”

Reading Sidik Fofana’s debut Stories from the Tenants Downstairs was especially meaningful for me because my friend B. recommended it to me when I was staying at her house last week, and she reads my book recommendations all the time but it’s not so often that I get to return to the favour. And what a rewarding favour this was, 8 stories from the perspectives of residents of a Harlem apartment building whose owners are pushing tenants down and out in a project of redevelopment and gentrification, all this the quiet backdrop to the foregrounded experiences of characters ranging from Ms. Dallas, a teaching assistant (who moonlights doing security at the airport); her son Swan whose friend has just come out of prison and who imagines that everything has changed with the new Black president; Mimi, struggling to get enough money to pay her overdue rent; Kandese, who we meet first in Ms. Dallas’s class, whose father dies while they’re living in a shelter; Darius, venturing into sex work and notorious after a run-in with his favourite celebrity goes viral; Najee, another student in Ms. Dallas’s class, whose scheme to make money by dancing on the subway has tragic consequences; Quanneisha, a top gymnast turned drop out who has come to face a world she’d thought she’d left behind; and finally Mr. Murray, the old man who plays chess outside of the restaurant across the street around whom the community rallies when he’s forced from his spot, but he doesn’t respond to their good will in the way that he’s meant to.

And subverting expectations is what this book is all about, in terms of the characters, but also the stories themselves, each of which comes with the most devastating pivot, sometimes on an epic scale, sometimes unbearably subtle (the push of an elevator button at the end of one story that I will never get over). As a reader, I want things to work out for these characters, but Fofana, a public school teacher in New York City (as well as a celebrated short story writer out of the gate—not everybody gets a blurb from Lorrie Morrie), does not give us the satisfaction, the catharsis.

Instead, the reader sits with the discomfort, with the injustice, a situation as intractable as those of these characters who are part of a system that was never built to serve them. Sometimes, often, this is how it is.

May 3, 2024

Not How I Pictured It, by Robin Lefler

I read a huge pile of excellent books in February as I was recording interviews for the BOOKSPO podcast, and now that those books are out in the world, I have some catching up to do in terms of posting about them. And one of these is Robin Lefler’s second novel NOT HOW I PICTURED IT, which I just loved with my whole heart. In my conversation with Lefler, she mentions how life itself is stressful enough and therefore, in her fiction, she strives to give readers a holiday from all that and provide fun and pleasure instead, which she definitely accomplishes, but I also want to emphasize that this book is so good. That excellence and being a pleasure to read can go hand-in-hand, as they do in this “shipwreck rom-com” (I didn’t even know that was a thing!) in which the cast of a 20-year-old teen drama en-route to their reunion show end up stranded on a desert island. A great cast of characters with complicated ties to each other (both spoken and otherwise) have to come together to survive, and also figure out who among them is the traitor who instigated this disaster and might still be putting them all in even more danger. Protagonist Ness—who fled show biz years ago and now lives in Toronto unclogging drains in the apartments she owns—is definitely regretting her instincts to avoid being a part of the reunion project in the first place, although the chance of rekindling her connection to her dreamy ex-boyfriend Hayes means: it’s complicated. Funny, sharp, and full of heart, I loved this book.

May 1, 2024

Who By Fire, by Greg Rhyno

In his excellent, riveting, heartful and hilarious second novel, Who By Fire, Greg Rhyno pays tribute to the fact that all the best classic detective novels always include some dame. Although his dame is not just any dame, instead Dame Polara, truly an original, only daughter of legendary PI Dodge Polara, whose brain is now scrambled after a stroke. If elder care wasn’t stressful enough, Dame is recently divorced, her latest IVF round has failed, her dodgy landlord keeps demanding she catch up on rent bills she can’t afford, and her straight job at Toronto City Hall working with heritage preservation is starting to seem pretty futile, particularly as a string of arsons take down one listed building after another. In spite of her best instincts, and out of desperation, Dame finds herself taking on a domestic case on her dad’s behalf, though she’ll be performing the investigation herself, which shouldn’t be so hard, right? After all, she’s the kid whose dad used to lock her out in the cold in order to deliver essential lessons in lockpicking, and she’s tagged along on all his stakeouts. But it turns out the case is connected to something sinister afoot in the city, and the true culprit is closer to home than Dame will ever imagine, putting her in serious danger, and forcing her to rely on her wits when the stakes have never been higher. I loved this book. A pitch-perfect pleasure.

April 30, 2024

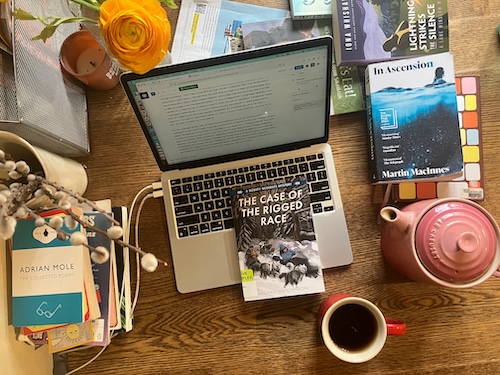

Lightning Strikes the Silence, by Iona Whishaw

There’s not much I love better than a return to King’s Cove, the bucolic hamlet near Nelson, BC, where the fictional Lane Winslow makes her home after a tumultuous WW2 during which she’d served as a special agent, utilizing her quick wits and affinity for the Russian language. When Lane arrives in 1946, England left behind her, she’s envisioning a quiet life, a chance to dedicate herself to writing, a retirement of sorts, even though she’s still young herself, but it seems that fate disagrees, as she stumbles across a body and manages to solve the crime, in partnership with the Nelson Police Department, a partnership that’s solidified with Lane’s relationship and eventual marriage to Inspector Frederick Darling a few books into the series. And now we’re on Book 11, Lightning Strikes the Silence, and it seems that Lane’s life hasn’t been quiet for a moment, and is even less quiet than usual when the sound of an explosion is heard high on the mountain above King’s Cove. Meanwhile, in Nelson (on Baker Street!), the local jeweller has been found dead, his office ransacked, and Inspector Darling is a bit pleased about having come upon his own corpse for once, without his dear wife’s involvement, but it won’t be long before Lane is embroiled in the case as well, in addition to caring for a young Japanese-Canadian child found injured by the explosion site. In 1948, with the war long over, Canadians of Japanese ancestry are still forbidden to return to coastal areas, their homes and livelihoods taken from them, and anti-Japanese racism is rampant. Will goodness triumph? Will Lane and Darling crack the case? Will Ames finally do something with that engagement ring he’s got hiding in his pocket? Book 11, and the series gets better and better. Lightning Strikes the Silence does not disappoint.

April 24, 2024

Understanding Carries the Light

“Wisdom is valuable. But the ability to find understanding is a gift that all creation enjoys… In some ways, you can think of wisdom of light. But it is understanding that carries the light. Understanding is what wisdom travels through.” —from The Case of the Rigged Race, by Michael Hutchinson

I really love the Ontario Library Association’s Forest of Reading Program, mainly because it’s like our family’s version of sports. (Librarians put together different reading lists for all ages, and school children vote for their faves, culminating in an absolutely bonkers in-person festival every May.) My kids’ schools do a good job running the program, but I borrow the books from the public library too just to provide more of a chance to get through the lists. And not all the books end up working for my children, which is fine, because I want to empower them as readers to follow their own instincts and make their own choices. But when Iris couldn’t get into The Case of the Rigged Race: A Mighty Muskrats Mystery, by Michael Hutchinson, a member of the Misipawistik Cree Nation, I didn’t want to just let it go. Even though I understood that it was not her kind of book—about mostly boys, a dog-sled race, the cover lacks an image of a tween girl sipping boba—but I was thinking about Elaine Castillo’s essay collection How to Read Now and how to be white is so often to assume oneself to be “the expected reader” of a story, no adaptations or great leaps necessary. And I wanted Iris to make the leap of reading a book for which she was not necessarily THE expected reader—Hutchison’s series are set on a Northern reserve and are a rare example of middle grade fiction in which an Indigenous kid would see themself represented. But sometimes (almost all the time) in parenting, if you want to make things happen you have to put your money where your mouth is. So Iris and I sat down and read it out loud together.

And am I ever glad we did. I was not expecting the experience to be so rich, the book itself to be so meaningful. A story about a gang of pre-teen cousins solving crimes sounds like a lot of stories I’ve read before, formulaic and flimsy-of-plot, but Hutchison’s novel (Book Four in a series) is the real deal, which is the kind of thing you know for sure once you’ve read an entire book out loud. Complex vocabulary, lots of fun wordplay, moral conundrums, flawed adult characters whose struggles are shown with real empathy, a portrayal of the realities of northern rez life (the prices at the grocery store!), carefully drawn protagonists, and a mystery that was interesting to unravel—I didn’t see any of that coming. But I especially didn’t expect the kids’ grandfather’s lesson—quoted above—to resonate so strongly with me, and to illuminate so many of the problems that occupy my mind half the time.

Wisdom is light (and so is righteousness), “but it is understanding that carries the light.”

What a gorgeous and absolutely necessary message. I’m so glad I got to receive it. Nice pick, OLA!

April 23, 2024

The Time of My Life: Dirty Dancing, by Andrea Warner

If you’ve read my second novel Waiting for a Star to Fall, in which Dirty Dancing features as a plot point (“Brooke had never seen an abortion in a movie before, and it was surprising, because Dirty Dancing was over thirty years old. So it should have been a throwback, but it was something very new: the character who wants an abortion. There is no other alternative, it doesn’t even make her sad, and she doesn’t change her mind at the last minute, or have a miscarriage as a convenient trick to avoid being an agent in her own destiny. She isn’t even sorry… [And] it seemed symbolic that no one had to live in shame. You could be a fallen woman, and then get up on a stage and dance. This was a huge revelation for Brooke, who had never even considered the possibility, the number of ways a script could go.”) then you’ll know that this movie means a lot to me, and Andrea Warner’s The Time of My Life: Dirty Dancing, a contribution to the ECW Pop Classics Series, only deepened my affection and admiration. Warner explores the movie’s roots as based in “the classic Jewish value” of tikkun olam, its celebration of liberal idealism before the ’60s got complicated, the subversiveness of a film whose entire plot hinges on abortion (screenwriter/producer Eleanor Bergstein was deliberate about that!) at a moment when American women’s reproductive rights seemed assured, and how its iconic soundtrack is the bedrock of the film. Andrea also fangirls in typical Andrea Warner fashion, sharing her own personal connections to the story and also critiquing the film for its shortfalls, how it appropriates Black culture and lacks intersectionality—demonstrating both this is a film substantial enough to be worthy of critique and that LOVING ALL OF ANYTHING (in the way that Baby wished Jerry Orbach could love her) means grappling with the ways it disappoints us too.

April 22, 2024

All In Her Head, by Misty Pratt

Misty Pratt is contending with all kinds of threads in her first book All In Her Head: How Gender Bias Harms Women’s Mental Health, including her own personal story of struggling with mental illness, and that of her grandmother—Chapter One begins, “I was five years old the night my grandmother lost her mind.” Pratt is also a researcher whose approach to her subject is based in science, such a basis only underlining that approaches to treating mental illness so often are not, but then neither are many alternative therapies, and that while mental illness is real, women’s experiences are also affected by a society rife with sexism and inequity, violence against women, and the pathologization of femaleness. Maybe it’s not just “all in her head,” but also sometimes it is, or else it’s in her body, or her family, or her workplace, and that’s not nothing. All this tangle of understanding and experience resulting in loud binaries like SSRIS for everyone vs. anti-psychiatry movements, but Pratt manages to blaze a path through the noise to suggest a kind of middle-ground to contend with the inherent complexity of mental illness (that anyone who’s thinking about it has to be contending with all kinds of threads or else they’re kidding themselves) which necessitates care and precision in applying treatments, as well as the message that women themselves are not broken. Pratt notes that puberty, pregnancy/childbirth and menopause are all times of great hormonal shifts when girls and women are especially vulnerable to mental illness, and imagines how different things might be if this reality was seen as normal as it actually is. Which is not to say that women have to suffer through these periods of their lives, but instead that patients deserve care without the message that there is something broken about them as people, and that researchers and doctors could put the pieces of the puzzle together to affect a more holistic understanding of just what women’s mental health might look like (and how anti-depressants affect them—Pratt cites a study stating that females are exposed to “higher blood drug concentrations and longer drug elimination times than males.”)

Pratt spent years trying to wean herself from anti-depressants, only to have withdrawal symptoms knock her right back down again, and she received very little guidance throughout this process, doctors telling her that she should just stay on the medication because it was simpler that way, because her children needed her to be functioning, internalizing the message that she was flawed and broken, that her mental illness was a genetic inheritance that had to define her. But this would turn out not be the case…

There is not cure for mental illness, Pratt writes, but that doesn’t mean that healing isn’t possible. And she shares her own journey to a deeper understanding of her experiences with psychiatry and medicine, making shifts in her life, working with good therapists, learning that feeling (and even feeling BADLY) is a normal part of being, that her anxiety isn’t just all in her head but also the result of living in a world where terrible things can happen but also that it doesn’t have be debilitating or a guiding force in her life.

And don’t worry, her conclusion is not prescriptive—after decades of people suggesting she try yoga or meditation, she knows that these one-size-fits-all cures are rarely helpful. And while there will be readers who might struggle with their lived experiences of mental illness running counter to Pratt’s (people who are all too happy to continue with their medication, for example), this is very much the point of the book: that everyone’s trajectory of mental illness and wellness will be different.

But through the lenses of gender and gender bias, those different trajectories can all be better understood so that patients can learn to tell a different kind of story, one of wholeness, strength and worth.

April 18, 2024

Book By Book: An English Journey

I wrote about our trip to England via the books I read on our travels, and you can read it on my substack. It was really long and kudos to anyone (everyone?) who reads all the way through. Check it out here.

March 28, 2024

Sharp Notions: Essays from the Stitching Life, edited by Marita Dachsel and Nancy Lee

I’ve been around for a little while, and I think it’s safe to say that Sharp Notions: Essays from the Stitching Life, edited by Marita Dachsel and Nancy Lee is the best literary anthology I’ve ever read. It’s a beautiful volume, as aesthetically as pleasing as you’d expect for a book about art, a beautifully crafted object in its own right, complete with colour photography of beadwork, quilts, Kelly S. Thompson’s knitted bull terrier, a conversation in embroidery, and needlepoint.

I’m not actually sure of what the difference is between embroidery and needlepoint (I’m a lapsed knitter myself, without much of a stitching life at all) but I still really loved this book, the different approaches of its essayists, the capaciousness of “the stitching life” in general and its connection to many different backgrounds and traditions, which means that every reader has something new, and fresh, and inspiring to say.

A common thread (oh, no. I’ll stop…) is the way that various kinds of stitching have sustained the writers through periods of difficulty, how needle crafts have managed to be transportive at moments when the crafters themselves weren’t going anywhere. My favourite piece was Jess Taylor’s, a meditation on pain, healing, trauma, and productivity. I loved Anne Fleming on knitting and gender; Danielle Lussier on bringing Indigenous beading traditions to her PhD thesis; Laura Cok on infertility and knitting for a pregnant friend’s baby; Lorri Neilsen Glenn on the stitches that have been with her throughout her life; Rob Leacock on knitting as a way to be alone; Carrianne Leung on stitching her way through pandemic days; and Theresa Kishkan (such a beloved writer!) on stitching through uncertainty.

These essays are stories of connection, with the past, present, and future. Stories of creation, solace, and possibility. These are stories of kinship, and it’s a privilege to join the fold through reading.