January 4, 2024

Apples on the Windowsill, by Shawna Lemay

If you’ve been following, you’ll know that I’ve been rethinking a lot of my social media habits with the advent of the new year, habits that I think were defined by the pandemic when Instagram was of one of the few means of connection in a time of stark isolation, and also gave me a real sense of what everyone was going through (which is to say, a lot). And one of the great joys of my online life in more recent years has been the vicarious excitement of seeing people returning to the world, doing those things that they were baking bread instead of doing in 2020, all of the adventures and connections the loss of which they’d been profoundly grieving. I knew what it meant when Shawna Lemay finally returned to Rome, is what I’m trying to tell you—I’d become that invested in the story she was telling. And now I’m thinking of all of our pandemic Instagrams as still lifes, these windows into each other’s worlds which seemed especially essentially when the life had gone completely still.

Shawna Lemay’s new essay collection is the first book I’ve read in 2024, and while it’s called Apples on the Windowsill, it’s as much about lemons, not only about how the light falls on their unwinding rinds, but also what we do when life gives them to us. Which is to say, put them in a bowl and take their picture, and notice them, how they absorb the light, and how they change, the same way that Lemay documented a series of still life images throughout 2020-22, images that included such various items as pop tarts, Kraft dinner, a crystal bowl filled with strawberries, and various arrangements of grocery store flowers that Lemay’s husband, a painter, would use in his own work. As will come to no surprise to anyone who has been following Lemay’s blog for the past few years, Bruce Springsteen is referenced again and again throughout this collection, and this quotation from an interview comes close to summing up Lemay’s focus in her book: “What do you do when your dreams come true? What do you do if they don’t?”

Apples on a Windowsill is a meditation on being human, and on staying human (soft and porous) in a world that makes this difficult. These are essays about marriage, and being an artist, and being the wife of an artist, working at a library, and about finding inspiration in the ordinary. As I begin a new year, I also find these essays are a helpful guide for how to be, and how to see, and I underlined all kinds of passages: “The magic trick of art, and perhaps particularly still life, is to remind us above all that there is beauty at the same time as evil. Evil is a given, but beauty persists. The magic trick of still life is that it reminds us that we’re not alone. The magic trick of still life is that it’s really not a trick at all.”

December 31, 2023

204!

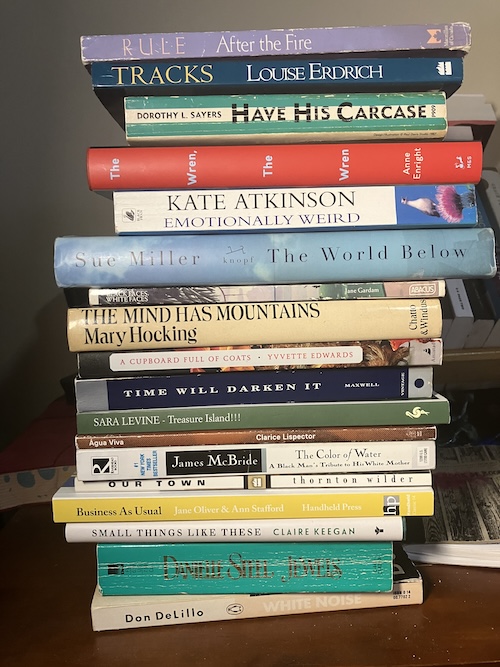

For a long time, or at least as long as I’ve been keeping track of books I’ve read, I’ve had a vague desire to reach the milestone of 200 books read in a single year, a milestone that proved elusive again and again as I clocked in around 175 books year after year, more or less. But 2023 began, in these terms, most promisingly, as I managed to read more than 20 titles in the month of January (thanks to a week of holidays after New Year’s, and a few short titles [Annie Erneaux, hello!]). And I’ve been able to build on that momentum ever since, my goal looking more possible than ever by mid-December, and so I decided to buckle down and get ‘er done while partaking in my absolutely favourite holiday reading ritual, which is finally getting around to all the random titles on my shelf I’ve been acquiring from secondhand bookshops and little free libraries and other serendipitous places over the past few months. My other reading goal, in addition to achieving that 200 books milestone, is curating a book stack that’s weird and surprising and looks like nobody else’s. And I did it! In fact, I did both its, and take a look at this book stack that has filled my days over the past two weeks as I’ve done almost nothing else but read, aside from some delightful holiday fun with my family. (Signs I’ve perhaps stayed too close to home include a journey up to Dupont Street yesterday, for which I decided it was necessary to take a train.)

I love this book stack, the last books I’ll have read in the year 2023, such a rando stack of titles:

- White Noise, bought secondhand after an essay in the New York Times about its relevance to our current moment, which was absolutely true, but also I didn’t love it so much, and also it’s one of so many books that I read in my 20s and didn’t understand was mostly supposed to be funny.

- Jewels, because what is a rando book stack without actual Danielle Steel. January 2024 will herald the launch of my substack, which will replace my newsletter, but be much of the same, except for a featured essay every month for paid subscribers, and the first one will be about Jewels—and you’ll be able to read it whether you’re paid or not because I’ve decided to make the first three essays free.

- Small Things Like These, because novellas are necessary when you’re scrambling to finally reach your goal of reading 200 books in a year for the first time ever, plus it was for sale by a new bookseller at one of my favourite cafes, and a Christmas book to boot. I loved it.

- Business as Usual, an epistolary novel about a young woman making a career in a London department store during the 1930s, a gift from my friend Nathalie, and I found it ridiculously delightful. (Epistolary novels are also good when you’re trying to rack up an impressive number of reads.)

- Our Town, which I’d never read or seen performed (I think you have to be American for that…) but was interested in after reading Ann Patchett’s Tom Lake, as Patchett herself intended with her novel. Also a play, very short, you know where I’m going with this.

- The Colour of Water, which I found for $2 after reading MacBride’s latest, The Heaven and Earth Grocery Store. This 1996 memoir is so remarkable, and connects interestingly to the novel.

- Agua Viva, by Clarice Lispector, whose strange books I can appreciate because they’re short, and I actually liked this one a lot, though it’s not completely my cup of tea.

- Treasure Island!!!, which I’d been wanting to read for years. I think this one used to be Nathalie’s too, and I stole it when sorting books donated for our school book sale. It was totally bonkers and nutty and I will probably never think about it again, but it was fun and horrifying, which is an unusual combination.

- Time Will Darken It. I just love William Maxwell so so very much and look forward to making my way through all this books. I love their subtlety, their play with form, their tenderness, how well he writes women and also how beautifully he writes men. (The bad thing about immersing one’s self in old books, however, is the frequency with which “the n-word” appears, and this was the first in the stack, would not be the last. For someone for whom that word is deeply personal and as wounding as that weapon-word could be intended, reading old books must be an absolute minefield.)

- A Cupboard Full of Coats, purchased secondhand in cottage-country this summer. I’d loved Edward’s second novel, which I was turned onto after her interview with Donna Bailey Nurse. Her debut was nominated for the Booker Prize and I found it enormously moving, strange and surprising.

- The Mind Has Mountains was one of two books I purchased at the Victoria College Book sale by Mary Hocking, an author I’d never heard of, and it was so weird and interesting…though I eventually ran out of patience. It’s part horror story, part bureaucratic tale of the reorganization of municipal government. Published in 1974. Hocking has always been sort of obscure, I think, though I managed to find a Facebook group called “Mary Hocking readers” and I became its 35th member.

- Black Faces, White Faces, another Little Free Library find. Jane Gardam’s first book for adults, about British expatriates in Jamaica. I loved it.

- The World Below, which I read all day on Christmas (my children having received video games, you see). I love Sue Miller SO MUCH and this might be my favourite of all of hers that I have read. Adored it. Even better, I found a beautiful new edition of her novel Family Pictures at the used bookstore yesterday, which means I still have more Sue Miller before me.

- Emotionally Weird was a Kate Atkinson book I read before I (and the world) properly understood what Kate Atkinson was, but after I’d fallen in love with her brilliant debut Behind the Scenes at the Museum AND I DID NOT LIKE IT and gave my copy away. It was too precocious for its own good. But having read so so much more Kate Atkinson since and having a better idea of what her literary project was in general, I wanted to revisit it, and guess what: I STILL DID NOT LIKE IT. Even brilliant writers miss the mark sometimes.

- The Wren, the Wren. I got this book for Christmas. Truly a book to be savoured, Anne Enright’s best yet? I loved it so much.

- Have His Carcase was a Harriet Vane/Peter Wimsey mystery and it’s so so wonderful but should also be 100 pages shorter, but maybe I’m just saying that because I didn’t actually care about precisely how the mystery was solved—there was about fifteen pages devoted to decoding a letter, deciphering broken down in mind-numbing detail. Either you like this stuff or you don’t, but if you’re the latter, there is always skimming, thank goodness, and so I also had a very good time.

- Tracks, which I bought at a yard sale in October, Erdrich’s third novel, rich and compelling.

- And finally, After the Fire, which I stole from a cottage library the summer before last (or maybe I actually rescued it, because it had become a habitat for mildew). I liked many things about it, and Jane Rule is a really interesting writer, but it also had mildew growing in it in a metaphoric way. Still, I am really glad I read it, especially since I found inside it a bookmark from Long House Books, which I’d never heard of, but which was located just metres from my house at 497 Bloor Street West, and—according to this blog post—stocked exclusively Canadian titles, which is such a wonderful idea (and not the least bit limiting).

December 7, 2023

We Meant Well, by Erum Shazia Hasan

“The fire became its own story. The great fire. People spoke of it as a temporal event, “before the fire,” “after the fire.” It wasn’t linked to anything other than to itself and time. There was never any blame, only mention of misfortune. Everything happened in such fragmented pieces that seldom were connector strings drawn between events. It was its own monster. People would talk of where they were during the fire. They recounted the miracles, the people who survived. They relived the losses. They have anniversaries. And time kept going. The fire had nothing to do with the Todds and the Toms, their umbrellas and baseball caps, or the fact that a mass movement of people had been forced, increasing risks and pressure in a small dense location. It had nothing to do with the fact that my mutual funds back home, which I’d set up when I was eighteen, had investments in the mining company that Todd worked for. No, the fire was what it was. An unfortunate event. Like Lele’s rape.”

Erum Shazia Hasan’s WE MEANT WELL (longlisted for the Scotiabank Giller Prize) begins with a phone call in the middle of the night received by Maya at her home in Los Angeles. There is an emergency in the unnamed African country to which Maya has been tied to for years through her work in International Aid, work she is yearning to leave behind for a fresh and less complicated start so that she might be able to be more present (both physically and otherwise) for her husband and young daughter. But it’s work that has changed her, and so has the place, Likanni, creating what seems like an unbridgeable distance between Maya and those who’ve never known the struggles of life in the Global South—her husband in particular, a high flying corporate lawyer. Who, Maya is aware, is having an affair, just one of the reasons—she realizes—he so easily lets her leave again, but she also knows that he knows that she’d be going regardless, because Likanni—and the ways that life there seems real in a way that her sanitized American existence so rarely does—has become a compulsion that’s unshakable.

The stakes are always so high—maybe that’s it? And perhaps they’ve never been higher than now as a colleague has been accused of raping a local woman who’s worked in their charity’s office. And now Maya has arrived to deescalate the situation, to smooth things over to keep their donors happy while also maintaining trust from the community, with whom she’s always had strong ties through her work. The matter boiling down to a simple he said/she said situation—but of course there has never been anything simple about that, WE MEANT WELL examining the space between all things (B)lack and white, a space embodied by Maya herself as brown-skinned woman, an American adopted as an infant from Bangladesh, a person who ever benefits from white privilege in a place like Likanni.

WE MEANT WELL is a novel of ideas (as well as part of a developing canon of works by Canadian writers about the complicated reality of NGOs), but also a terrific, fast paced, plot driven work that’s horrifying, fascinating, and absolutely gripping at once.

December 5, 2023

The Clarion, by Nina Dunic

I really loved The Clarion, a strangely shaped novel about loneliness and connection, a quiet story of two siblings launched into the world from a difficult childhood whose adult trajectories (told in alternating chapters) are very different, the narrative reflecting that. Peter’s world is small, and his story takes place over a handful of days, beginning with a monumental one as he auditions for a spot playing trumpet in a part time gig at a local restaurant. Peter is an unlikely performer—he’s nondescript, unassuming, and while he plays the notes, discerning listeners can tell that he doesn’t feel them. He works behind the scenes in a restaurant kitchen—a job his sister got him—and finds connection and release at a local bar whose DJ’s tracks are mesmerizing and allow Peter to be absorbed into the crowd, to become part of something larger than himself.

Whereas his sister Stasi feels she is too much of the world, and has lost herself within it, in serving its goals and spending so much of her life caring for first her troubled mother, and then her brother. Striving to succeed in the corporate world, the hollowness of all this becoming apparent when she’s passed up for a promotion. Her story—reflective of its larger scale—take place over several weeks as she contemplates her grief and listlessness, tries out therapy, and continues an affair that threatens to put her domestic life at risk, all the while just as lonely and lost as her brother is.

Are we all different or are we the same, is a question the novel returns to several times, a question of nature versus nurture, and the idea of a clarion call haunts the story too, a longing for a song to summon everyone, a common humanity. And the beauty of this book are the fleeting moments of connection where such a thing almost seems possible. However meagre, and also everything.

November 20, 2023

The Heaven and Earth Grocery Store, by James McBride

The luckiest thing that ever happened to me was the Little Free Library discovery of Deacon King Kong (in hardcover, even!), a novel that turned James McBride into one of my must-buy authors. That book was brilliant, huge in scope, full of play and wisdom and literary magic. And now I’m raving about McBride’s latest, The Heaven and Earth Grocery Store, set in a Pennsylvania community that’s home to Black Americans and Jewish European immigrants, and it’s just as strange and wonderful, a story to get lost in. A novel I’m finding it hard to find words to describe, arriving at “spectacular,” with emphasis on “spectacle,” because there’s just so much going on here. The way that McBride has constructed an entirely literary universe in Chicken Hill, with buildings with something going on (or being stored) on every single story, and tunnels dug underneath all that, the action never quits, which isn’t too say that so much of it’s not going on inside the minds of its incredible characters, fallible people of such feeling and depth. I just loved it, though it really was “a story to get lost in” at first, pitched—as I was—into 1925 with Moshe Ludlow’s vision about Moses as he strives to make a go of his theatre in Pottstown, Pensnsylvania; his wife, Chona, who works behind the counter in The Heaven and Earth Grocery Store and writes furious letters to the editor calling out the town doctor for marching with the Klan; the deaf Black boy being harboured in the basement from government agents who want to send him to a local asylum; Moshe’s bigshot cousin Isaac in Philadelphia; old Malachi, the world’s worst baker, and a tiny pair of cowboy pants; the neigbourhood gossip, whose name is Paper; not to mention Soap, and Fatty, and Nate Timblin, who had a different name before. And how do all these characters connect? Well, therein lies the adventure, a gorgeous tale of community, solidarity, and humanity. Larger than life, and somehow also its essence.

November 16, 2023

On Community

A thing I think about sometimes is how, about 15 years ago, there used to be these gatherings of people associated with publishing or who were publishing-adjacent—most of which I did not attend, though when I did, I usually felt like a numpty—after which there would be ecstatic posts on Twitter saying things like, “If they’d dropped a bomb on The Ferret and the Firkin tonight, there’d be no one left in Canadian books!” How, at the time, I even thought this was true, and there was something reassuring in that, in the world and its subsections being so knowable, contained (and the solipsism to boot!).

And I’m not sure exactly what has changed since then—if the world actually has become more complicated, fragmented, if social media is the culprit, or if social media has only made it clear that life was never so tidy, that no single community could ever be so defined or fit in a pub (in Toronto, no less!). Or maybe it’s just that I’ve gotten older and have seen for myself that community and belonging and understanding is a bigger, weirder, harder project that I ever knew, and sometimes the amorphousness of it all, of everything, causes me incredible anxiety.

And that amorphousness—of community, of the idea of community, of the way we talk about “the [FILL IN THE BLANK] community—is the subject Casey Plett takes on in her book On Community, part of the Field Notes series of long essays inspired by big ideas. A book that, like all my favourite nonfiction, not just managed to articulate my preoccupations—my anxiety around community’s amorphousness; how the idea of community can paint over complexity; how perpetually difficult community is, even with its rewards; ideas of belonging and who doesn’t belong; policing borders and what you lose when you don’t, and what you lose when you do; and so much more—but to connect the dots between them in a way I didn’t see coming.

Plett brings a fascinating personal perspective to her essay as a trans woman (ie a member of “the trans community;” “the LGBTQ community;” [by the way, I think the first time I ever heard the absurdity of all this considered was—somewhere?—a laughable reference to “the fat community”]) and as a Mennonite who grew up connected to the communities in Manitoba from which her parents had come. Both are groups in which the idea of community is central, though it manifests in ways both good and bad (and similarly too—ideas of belonging or not, of excommunication, of who does the work and who reaps the rewards, of who gets called out, and whose transgressions remain unremarked upon).

From New York City to Windsor, Ontario; from Plett’s family’s stories and the books of Miriam Toews to her adventures couch-surfing across North American to promote queer small press titles; to whether the internet enhances connection or breaks it (she references characters in Toni Morrison’s Sula hating on the telephone because it meant nobody ever dropped by the house anymore); and the fact that any one community can be embody many different things at once; Plett’s essay is a thoughtful, rich and engaging unpacking of the complexity behind simplistic ideas, and a clear-eyed consideration of what really is a universal human experience.

November 13, 2023

Kiss the Red Stairs: The Holocaust, Once Removed, by Marsha Lederman

I think I learned about the Holocaust wrong. (It is possible that everybody has learned about the Holocaust wrong, no matter how they learned about it.) A decade and a half after Marsha Lederman did, I came of age in a public school system that had evolved to include the Holocaust in the curriculum, having read so many middle grade and YA novels about Holocaust experiences, and having taken at least one school trip to the Holocaust Museum in Toronto. I read about Nazis in so many books before I’d ever heard them spoken about in conversation, so much so that I remember being surprised when I realized they weren’t called “nazzies,” to rhyme to “snazzy.” When my family talked about the war, you see, we talked about “The Germans,” against whom both my grandfathers had fought in the Navy, and for the longest time—such a shamefully longest time—I’d understood that the whole purpose of the second world war, and my grandfathers’ service, had been liberation of the Jews. We were the good guys. It was all quite straightforward. Moreover, the stories I read in children’s books had all been sanitized, from the perspective of spunky kids who survived. Anne Frank and her fate, in my education, had been an outlier. And all of it, all of it, was in the past.

The problem with the way I learned about the Holocaust is that I still can’t quite believe that it happened, which is not to say that it didn’t—it did; I’ve been to Dachau; I also can’t believe that there are people who make a point of refuting these things—but just that the scale of it, the brutality, the evil, is still unfathomable to me. And I know that the difference between me and so many Jewish people is that, for them, it’s all too fathomable after all, a knowing they carry in their bones, one that’s literally part of their DNA.

Which is not to say that the way that many Jewish Canadian children learned about the Holocaust was necessarily the right one either. Beyond the DNA, and the fact of a tattoo on one’s mother’s arms, the conspicuous absence of grandparents, aunts and uncles and cousins—which were Lederman’s experience growing up in Toronto in the 1970s—she and her peers were made to watch upsetting films, were subject to terrifying exercises that trained them to imagine Nazis around every corner, experiences that Naomi Klein recounts from her own upbringing in her latest book Doppelganger and names not as acts of remembering, but instead acts of re-traumatization. (Klein also writes that “Our education did not ask us to probe the parts of ourselves that might be capable of inflicting great harm on others, and to figure out how to resist them. It asked us to be as outraged and indignant at what happened to our ancestors as if it had happened to us—and to stay in that state.”)

As someone who lives with anxiety and was on a list receiving the most alarming updates from my local Jewish community centre (of which I am a member) in the days after October 7, I am going to boldly assert that I understand a single percentage point of what my local Jewish community in general were going through at that time (some will disagree and that’s fine): it was scary and awful (and continues to be). And I’ve been thinking about that ever since, as well as about the very different contexts in which me and my Jewish neighbours are living, different contexts that were wholly invisible to me until now, contexts in which flags and phrases have entirely different meanings, the ideas of peace and ceasefire. October 7 itself, which to me is a single piece of a larger nightmare stretching back into the past and—devastatingly—into the future, and I can’t regard it as an atrocity onto itself because of how the brutality and loss of life has just been compounded every single day since then. (There was a line from Kate Atkinson’s new book that I was reading that very same week that struck a chord: “The old man was tired… Tired of the fear everywhere. It had been an opportunity to make the world anew, but they were, inevitably, failing.”)

I wanted to read Marsha Lederman’s Kiss the Red Stairs: The Holocaust, Once Removed. I’d already been called “an enemy of the Jewish people” in my DMs in the last couple of weeks, which tells you plenty about the level of fervour at which a lot of people are operating these days (I am definitely not an enemy of the Jewish people, and also the person declaring me as such wasn’t even Jewish, just nuts. Side note: I have a theory that no one who’s ever screamed at anybody on the internet to “educate yourself” has ever actually been smart.) Having felt an iota of the dread that so many were experiencing post October 7, I’ve been curious to gain a better understanding, and so Lederman’s celebrated memoir about growing up as the child of Holocaust survivors (her parents’ first home in Canada was just around the corner from my house) seemed like just the thing.

It’s such a good book. Lederman begins in the wake of a devastating divorce wondering if something in her parents’ experiences (both of their entire families were murdered; Lederman’s father managed to get false papers and spent the war in Germany hiding in plain sight while working as a farmhand; her mother had been at Auschwitz and worked as a slave labourer) had lodged itself in her psyche making sadness and despair her destiny, the rest of the memoir an act of repair as she learns about the science behind epigenetics and trauma, and also attempts to fill in the blanks in her family history, to come to terms with what her family had lived through in order to create a different kind of future for her son. She writes about the pervasiveness of antisemitism, however, and what it felt like to see neo-Nazis marching with their tiki-torches in Charlottesville in 2017. Not all of the horror resides just in memory—which was clear to so many people when the details of October 7 emerged, people stolen from their homes and families, the rest of the world quibbling about the details and just *how* exactly the babies had been murdered, as if that was what mattered. The parallels are uncanny, but then so they are as well to the devastation in Gaza ever since then, people cut off from power, water, and sanitation, more than ten thousand lives lost (a statistic I saw someone counter with the fact of high birthrates, a detail whose callousness blew my mind).

I think what was most wrong about how I learned about the Holocaust was the idea that it was a one-off, extraordinary in any way beyond its scale, and that there is a special category of humanity with the capacity to inflict such violence upon their fellow beings (although white people do tend to excel in this area.) And Lederman writes about this in her memoir, finding solidarity with descendants of enslaved African-Americans, Indigenous residential school survivors, and others. This kind of barbarism is not just part of the Jewish experience, but part of the human experience in general, and—at this moment of antisemitic and anti-Muslim rhetoric at such a disturbing high—we need to acknowledge that, and strive to be our better selves.

November 7, 2023

Roar, by Shelley Thompson

From its opening pages, Roar hooked me with its heart. Although if I’m being totally honest, I think I was truly hooked by the blurb from Sheree Fitch (whom I adore) on the back that reads like a Sheree Fitch verse: “Wow. Wow. Wow. I want to roar, READ THIS BOOK.” And I’m so glad I listened!

Roar is the debut novel from actor/director Shelley Thompson, based on her 2021 feature film Dawn, Her Dad, and the Tractor, the story of a family grieving the death of Miranda, its mother, as the younger child, once Donald, now Dawn, returns to their rural Nova Scotia community and the family farm after years of estrangement.

Elder sister Tammy has also come home from her life in Toronto, a prickly character to begin with, and she’s hurt to discover that Dawn, her sibling, now her sister, had absented her and her father from her story, all the while maintaining contact with their mother and actually being with her when she died. Tammy’s fiance Byron finds himself embroiled in the tension of the family drama, with a heightened awareness of the bigotry Dawn faces through his own experience as a Black man in their small town. Dawn’s father, John-Andrew, is at a remove from all of this by virtue of his reserve, but wanting to do good by his beloved wife and out of love for his child, he’s making small steps toward reconnecting with Dawn, although the road there is far from smooth.

The story moves between the perspectives of Dawn and her family (as well as some beautiful scenes from the haunting perspective of Miranda herself) to show how this family moves forward through these difficult days, grappling with the hurt of estrangement, difficulties around understanding Dawn’s transition, hate and bigotry from some corners of their community, and surprising love and acceptance from others. Dawn, who has always been herself, begins the task of refurbishing her mother’s old beloved tractor, this project reopening (and perchance healing) some of her father’s old wounds, and also finally bringing father and daughter together.

November 3, 2023

Four Books I Really Loved

These four books are going to have spots on my Favourite Books of the Year list for sure, so I want to make note of them them here, but (apart from Penance, which I read last weekend) they were also books just so thoroughly read for pleasure that I didn’t want the work of writing a proper review….

Penance, by Eliza Clark

I bought Penance after reading a review in the New York Times and I was so glad I did. Set in a desolate English seaside town (is there any other kind of English seaside town?) on the literal eve of Brexit, it’s the story of a teenage girl who is set on fire by a group of her peers, the novel framed as a Capote-esque true crime expose by a male author who has interviewed the girls involved in the incident, as well as the mother of the victim. Although by the end of the book, readers will be asking who isn’t the victim here, and while the dead girl hardly had it coming, this also isn’t a typical story of bullies gone homicidal—there are all kinds of dynamics at play, and there’s a centuries old curse, a legacy of witch trials, a haunted amusement park, and more, which made it a pretty satisfying read for near Halloween.

*

Games and Rituals, by Katherine Heiny

It’s possible that loving Katherine Heiny’s work could constitute a very large part of my literary identity if I let it, and a highlight of 2023 for me was that a new Heiny book was in it, just as I’d read everything else she’d written (and I guess it’s time to reread now). I didn’t love Games and Rituals as much as I did her earlier collection Single, Carefree, Mellow, but that’s a high bar, and I did love it enough to read an advanced copy during a snow storm in December and then buy a hardcover and read the whole thing again in April. All these months later, I’m still thinking about the story of the women dressed inadequately as she’s helping her husband’s ex-wife move, hauling boxes in the freezing cold, a woman she’d first encountered years before when the two of them worked a overnight suicide hotline together. Heiny gets compared to Laurie Colwin (I encountered her first as emcee of a literary event celebrated the reissue of Colwin’s work in 2021), but she also has Sue Miller vibes in mapping unconventional emotional terrain and reinvention of the family tree as family is made and remade. I love her.

*

The Rachel Incident, by Caroline O’Donoghue

I read this one over the August long weekend, partly on the beach, and it was incredible, twisty and full of surprises. It’s about an Irish journalist who lives in London covering Irish issues, their abortion referendum in particular, and she happens to be quite pregnant with her first child, all this the backdrop to a story of something that happened years before when she was a student in Cork and shared a house with her friend James, who’d been her colleague at a bookstore where they’d finagled a professor she’d had a crush on into holding a book launch for his academic book that really wasn’t of interest to anyone, but what happens that night changes the course of everybody’s life. A story of class, love, and friendship. I loved it.

*

Tom Lake, by Ann Patchett

I bought the hype, and the book lived up to it, but also I wasn’t resisting, and I think that’s key. A slow and cozy book, set during Covid lockdown. A mother’s three grown daughters return home to help with the family’s cherry harvest, and she tells them stories of her experiences playing Emily in productions of “Our Town,” the daughters still scarce believing that once upon a time, their mother was almost a movie star. This is a novel about mothers and daughters and their unknowability to each other in fundamental ways. It’s also an ode to Thornston Wilder’s “Our Town,” which I know absolutely nothing about (I think it’s quintessentially American…), and I enjoyed it anyway. Plus I found a used copy of “Our Town,” which I’m looking forward to reading soon.

October 19, 2023

Landbridge: life in fragments, by Y-Dang Troeung

“In the image of the land bridge, the ingenuity of refugee survival is laid bare alongside the scourge of permanent war. Backward from Cambodia to Laos, Vietnam and Korea, and forward to Afghanistan, Syria, and Yemen—how far can this bridge wind on?” —Y-Dang Troeung

This week was a sadly fitting week to read about war, about the terrible violence that human beings inflict on each other, what it means to survive it, what survival even looks like. And in the posthumous memoir by Y-Dang Troeung (a UBC Professor of English who died from pancreatic cancer in November 2022), survival looks like a life—a world—in pieces, in fragments, including letters to her young son, reflections on her experiences in Phnom Penh where she visits tourist attractions devoted to attempted genocide, contemplation of a tangle history of colonialism and Asian connections, news clippings from her own refugee family’s arrival in Canada in 1980 where they were personally greeted by Pierre Trudeau, this contrasted with images of his son—now Prime Minister—greeting refugees from Syria in 2015, and these are supposed to be happy endings, but the true experience runs much deeper and is more contemplated, and also war trauma never ends. Troeung shares photos from her family’s time in refugee camps, where she was born after her family’s survival of “Pol Pot Time,” the horrors branded on the psyches of her parents and her brothers, what it means to be just removed from that. She writes about growing up in Goderich, ON, and falling in love with the work of local writer Alice Munro, wondering if she’d ever see people like her and her family in any of Munro’s stories. “Now, over twenty years since I left Goderich, I have stopped waiting for stories like mine and my family’s to be written by the national artists. When, little by little, these stories do emerge, they come from refugees who write in poems and fragments. We, the children of refugees, let the stories we could never write drop through our fingers.”