January 12, 2016

The Babysitters Club, or What Comes Down Through the Ages

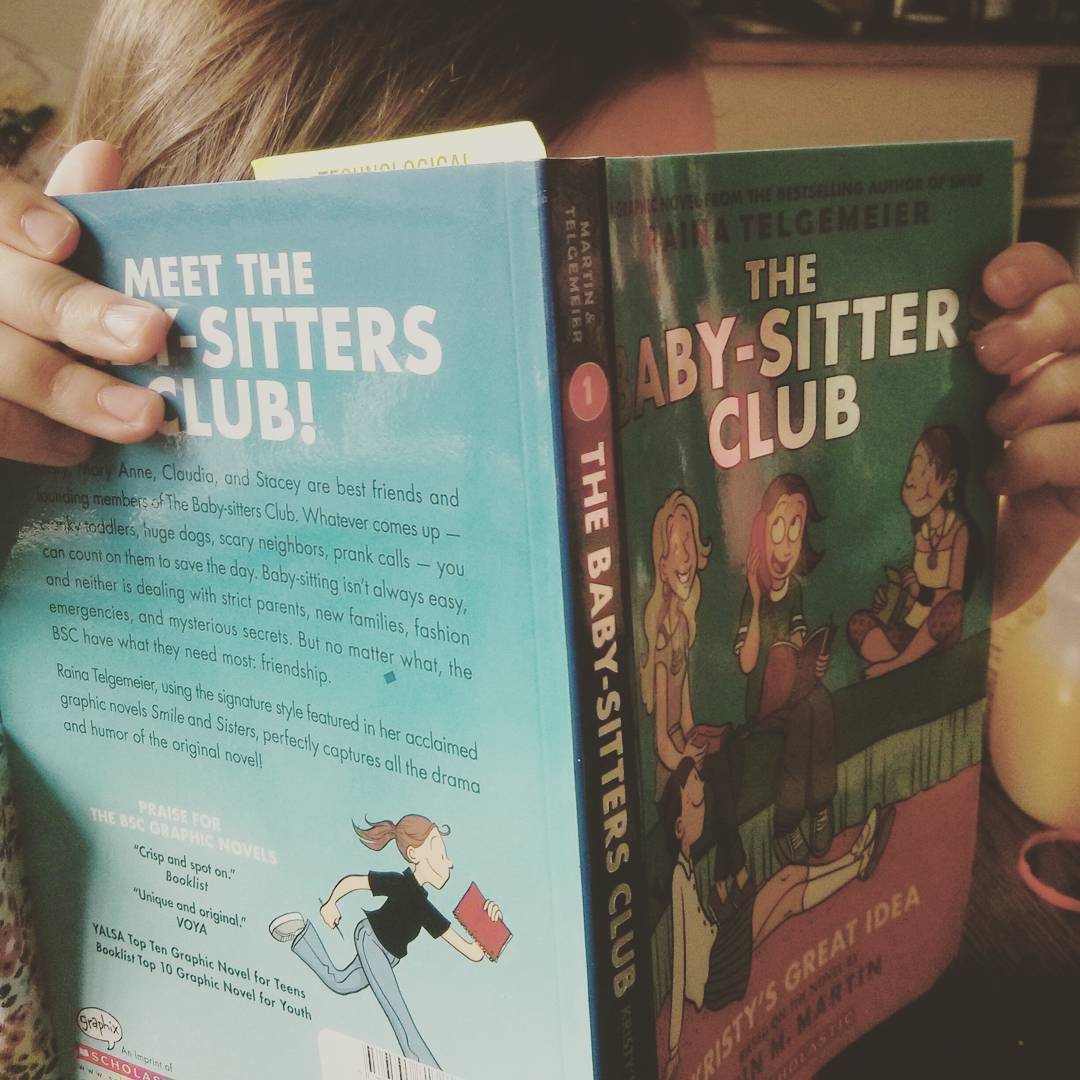

Whenever I start to worry too much about shaping my child’s cultural consciousness, I remind myself that at the age of ten I read The Babysitters Club series exclusively and that I once cried at receiving Swallows and Amazons for my birthday instead of Mallory and the Trouble With Twins. (Remembering this is why I try to read classic children’s books with my daughter, rather than expecting her to gravitate to them on her own.) I used to tick off BSC books in my Scholastic Book Order like they were going out of style, and refused to believe that they ever would go out of style. I remember a conversation with my mom about how it was a shame the books weren’t in hardcover because they fell apart in paperback and how was I ever going to pass them onto my own children the same way my mom had given me her Trixie Beldens and Cherry Ames. (I think had different ideas about hoarding then.) I recall my mom was skeptical about the books’ everlastingness.

It’s odd to realize that I was kind of right, however. The first book in Ann M. Martin’s iconic series (iconic, that is, if you were a certain kind of age in a certain type of place), Kristy’s Great Idea, was rereleased in 2006 in graphic novel form by the award-winning Raina Telgemeier, along with three other titles. Although it stayed peripheral to my experience until our friend Erin bought Harriet her own copy of Kristy’s Great Idea, and Harriet was hooked. She loved it. You can’t imagine how strange it is for your daughter to be telling you about how Kristy Thomas’s two brothers are called Sam and Charlie. That this kind of knowledge is the sort of thing that gets comes down through the ages. Who knew that The Babysitters Club would actually be a series of books that got passed on to my children?

But it’s not really so surprising, when you think about it. There’s always been something generative about the series. The characters themselves are types, but also specific down to their accessories (or lack of them—not everyone can pull off dangly parrot earrings), and that the books were told from all their different points of view enabled readers to try on these roles for size. This is just a starting point for how readers have taken ownership of these familiar characters and their favourite books. These are characters who live beyond the page, as attested to by the popularity of Babysitters Club fan fiction communities online. The books have generated blogs including those revisiting the entire series and another exploring its characters’ tastes in fashion.The series are also Buzzfeed bait: note The Definitive Ranking of All 131 Babysitters Club Covers Outfits. Artist Kate Gavino designed a series of book covers imagining the series had it taken place in 2014. I recall a few years back someone was making notebooks out of recycled BSC book covers. Not to mention that the series was self-generating—so many spin-off series, so many…recycled notebooks. Plus board games, movies, dolls, etc. And the imitation babysitting clubs the books must have inspired as well—though I do wonder if any of these were successful. From an entrepreneurial point of view, it was not the greatest business model. As a parent it would be most inconvenient to only be able to schedule babysitters twice a week and if Kristy Thomas had been a proper capitalist, wouldn’t she have kept all the babysitting jobs for herself?

But it’s not really so surprising, when you think about it. There’s always been something generative about the series. The characters themselves are types, but also specific down to their accessories (or lack of them—not everyone can pull off dangly parrot earrings), and that the books were told from all their different points of view enabled readers to try on these roles for size. This is just a starting point for how readers have taken ownership of these familiar characters and their favourite books. These are characters who live beyond the page, as attested to by the popularity of Babysitters Club fan fiction communities online. The books have generated blogs including those revisiting the entire series and another exploring its characters’ tastes in fashion.The series are also Buzzfeed bait: note The Definitive Ranking of All 131 Babysitters Club Covers Outfits. Artist Kate Gavino designed a series of book covers imagining the series had it taken place in 2014. I recall a few years back someone was making notebooks out of recycled BSC book covers. Not to mention that the series was self-generating—so many spin-off series, so many…recycled notebooks. Plus board games, movies, dolls, etc. And the imitation babysitting clubs the books must have inspired as well—though I do wonder if any of these were successful. From an entrepreneurial point of view, it was not the greatest business model. As a parent it would be most inconvenient to only be able to schedule babysitters twice a week and if Kristy Thomas had been a proper capitalist, wouldn’t she have kept all the babysitting jobs for herself?

Anyway, it makes sense, with Martin’s wholly realized fictional world, that Telgemeier would have so much to work with in these stories, and that the graphic novels themselves would be so successful. The books are empowering and feminist (these girls may have worked as caregivers, but caregiving was their business; strong feminist role models, paging Kristy Thomas’s mother, anyone? [before she married a millionaire], and how about their author who lived seemingly single in New York City and hated to cook?), and, as I’ve made clear, most inspiring.

Perhaps we should be collecting them in hardback after all.

October 12, 2015

My grandmother’s china

“I have your grandmother’s china for you,” her mother said. “She took good care of it.”

I highlighted this line from a story in Kelli Deeth’s The Other Side of Youth when I read it, the china emblematic of all the ways in which the lives of women my age have failed to progress in the manner that previous generations might have foreseen. All these boxes of china wrapped up in paper and boxed up in basements, and it means nothing now. I grew up in a house with a china cabinet, is what I mean, and it is very unlikely that I will ever have such an item myself, let alone a place to stand it.

Which is not to say that the domestic has no hold, that we don’t give any value to stuff. My Pyrex fixation certainly speaks to that (and I realize now that since the photo in the link was taken, I’ve acquired a set of turquoise Cinderella bowls, and also put a halt on all non-essential Pyrex acquisitions to keep things from getting too out of control). But what I don’t need is a massive collection of dishes and cups to be hauled out on special occasions, just the same way that I don’t need a parlour for afternoon callers. What I like about Pyrex is its usefulness, and then it occurs to me that there is a similar way around the grandmother’s china as well—what if I actually used it?

I have no recollection of ever seeing this china before—I didn’t pay attention to things like plates as a child, particularly if they were patterned with wildflowers. It is also possible that my grandmother didn’t set the table quite so formally when I was coming to visit. Although I do know my own mother’s wedding china intimately. I have no wedding china, but I have a vast collection of cracked and chipped dinner plates that it’s starting to seem shameful to feed my children from, and so I asked my mother if perhaps I could take a look at my grandmother’s china. If we could use them for everyday. Would that be more or less troubling, I wondered, than the plates remaining boxed up until the end of days, or else given away to a consignment store (where I would have totally bought them if I’d happened upon them)?

And so we took them, and now they’re here, unpacked in the kitchen. Some of them need cleaning—the gravy boat is still stained from some dinner more than a decade ago. But for the most part, the plates and cups are in excellent condition. Plates of various sizes, 10 of one, 8 of another, 11 side plates, 11 saucers and 9 tea cups. I wonder what they started with? Only 2 soup bowls—what happened to the rest of them? Or was soup more an intimate course, something best suited to a couple?

Predictably, I’m now a bit obsessed with my grandmother’s china. Who knew? Spode China in the cowslip pattern with a chelsea wicker design. There turns out to be a busy online marketplace for fervid Spode collectors, and now I’m lusting after Spode eggcups and a teapot. I also admire the buttercup pattern (seen here). The former curator of the Spode Museum Trust blogs about all things Spode here (and this is why I love blogs so: there is almost nothing under the sun that has not been blogged about yet). Spode was founded by Josiah Spode in 1770 in Stoke-On-Trent—Josiah Spode was almost an exact contemporary of another pottery-maker called Josiah but instead of a Spode he was a Wedgewood.

We spent this morning at the museum, which re-enlivened my delight in the thingness of things, and it occurs to me how much of my boredom with and dismissal of my grandmother’s things has to do with the idea that this is baggage, something to be carried and put somewhere. (My grandmother never ever put her china in the dishwasher, my mother tells me. We don’t have a dishwasher, so we will quite easily be able to continue in the same tradition.) But with the idea that these things could be used rather than put up on a shelf to be dusted—it changes everything. The best part about things in museums is what they tell us about ordinary life, and so it seems fitting that my grandmother’s china should become part of our ordinary life as well.

Which ensures, I suppose, that each piece will be eventually get broken and never be passed down to anybody, leaving nothing for us to be known by, our ordinary life an enigma to those who come after us, should they even care to wonder. A paradox—the Pompeii exhibit is case in point; does it matter if your frescoes are preserved if you’re dead? But I wonder if it isn’t better to simply live in the moment after all. From a person’s point of view, I mean, if not from that of an archivist.

September 16, 2015

A ride in the bucket

I’m something of a pathological truth-teller, which is a line I stole from Lauren Groff’s new novel, Fates and Furies, the book I’m reading right now. The interesting thing about that line being that the character described has a more ambiguous relationship to truth than the speaker supposes. Which is always the way. Truth is fudgy. I think I only have such a strong affinity for the principles of truth because lies are so easy, the slipperiest slope—and then anything one says ceases to have meaning, and then what is the point?

I’m something of a pathological truth-teller, which is a line I stole from Lauren Groff’s new novel, Fates and Furies, the book I’m reading right now. The interesting thing about that line being that the character described has a more ambiguous relationship to truth than the speaker supposes. Which is always the way. Truth is fudgy. I think I only have such a strong affinity for the principles of truth because lies are so easy, the slipperiest slope—and then anything one says ceases to have meaning, and then what is the point?

It’s true though I’m often willing to forsake a bit of truth for the sake of a story. Which is why I wouldn’t be surprised at all to have made up the whole thing, the story of my friend Britt and I driving down a country road outside Peterborough during the summer of 2000. How there was a hydro truck pulled over by the same of the road, a crew working on a Sunday. (At the time, I don’t think I knew the song, “Wichita Lineman”, or else I would have been humming it.) We pulled up alongside, and somehow had the nerve to roll down our window.

“Could we have a ride in your bucket?” I asked.

And I’ll never forget the so-perfect response: “I can’t think of a reason why not,” the crewman said.

And he even meant it.

And so the crewmen paused their work for a moment and gave us each a chance to put on a hardhat and take a trip up in the bucket. Violating more health and safety policies than I can dream up, though I was 21 at the time and didn’t think in those terms. Still though, we knew it was amazing. We took pictures. That vivid blue sky, the wispy clouds.

If not for the photo, I really wouldn’t believe it. I’m not even sure I really remember it happened. That ride in the bucket seems more like a figment. A figment of reality, if there exists such a thing. “I can’t think of a reason why not,” that crewman said—has there ever been anybody else with so limited an imagination? And yet. Perhaps he was dealing with a surfeit, head in the clouds literally and otherwise.

And I mention this story here now because for the past few weeks, I’ve been stuck in the past, working on a story whose roots are autobiographical. All this spurred on by my husband’s application for Canadian citizenship, and how I was rooting around in boxes to unearth his university degree (which confirms his competency in English). I found my diary from my final year of university, a diary that begins on September 14 2001 and is written by a girl who was dazzled and devastated by the world at once. And I found the scrapbooks I so painstakingly compiled back in those years, determined to preserve every single moment. Not yet understanding then that there are so many moments, if we’re lucky, more moments than ever could fit in a storage locker full of scrapbooks. Not understanding then either that I mightn’t want to hold onto everything forever. That there would be so much I’d want to let go.

When we moved back to Canada ten years ago, I got rid of a whole bunch of stuff. Diaries, scrapbooks, yearbooks, tossed out in black plastic bin bags. There wasn’t room for all of it. Who wants to go through life with so much baggage? But I didn’t get rid of all of it. Enough to fill a couple of boxes, from the years that were most monumental. So there would be gaps, big gaps, but I don’t regret it now. I don’t regret the bits I kept either, which become more and more precious all the time. But so too are the gaps, which allow me tremendous freedom both as a writer and as a human being. To let stuff go, to be allowed to forget, but also to fill those gaps with other things—creation.

To go for a ride in the bucket, I mean, whether it happened or not.

- If Creative Nonfiction is your thing, check out Amanda Leduc’s series this month on The Puritan’s Blog. She writes about Lucy Grealy and chutzpah, see Julia Zarankin on birdwatching and the pursuit of the strange, and Liz Harmer on writing without rules.

February 1, 2015

Wonder About Parents

The weekend was unexpectedly quiet, all plans cancelled, and unexpectedly long. Thursday night delivered a stomach ailment that felled all of us, and meant we spent Friday lying down and eating popsicles while a brutal winter wind raged outside, and we didn’t really miss it. The children slept for hours after lunch that day, which meant I got to spend the afternoon reading in the tub—such an indulgence. On Friday night, we watched episode 3 of Broadchurch Season 2—we’re wholly riveted, even when it gets ridiculous—before finally getting a good night’s sleep after missing Thursday’s entirely. Saturday was a lot more lying down, and then we watched Gone Girl. This morning we were ambitious enough to go skating, which was wonderful, but it’s all still touch and go—we’re still only 20 hours since the last time anyone threw up. But other than the sickness and far too much laundry and really only eating bread and butter and saltines, it’s been kind of a nice weekend. There is nothing like being ill to make one appreciate feeling better, and nothing like being ill with 2 small sick children to make one appreciate a spouse who is a partner in every sense of the word—for better or for worse.

The weekend was unexpectedly quiet, all plans cancelled, and unexpectedly long. Thursday night delivered a stomach ailment that felled all of us, and meant we spent Friday lying down and eating popsicles while a brutal winter wind raged outside, and we didn’t really miss it. The children slept for hours after lunch that day, which meant I got to spend the afternoon reading in the tub—such an indulgence. On Friday night, we watched episode 3 of Broadchurch Season 2—we’re wholly riveted, even when it gets ridiculous—before finally getting a good night’s sleep after missing Thursday’s entirely. Saturday was a lot more lying down, and then we watched Gone Girl. This morning we were ambitious enough to go skating, which was wonderful, but it’s all still touch and go—we’re still only 20 hours since the last time anyone threw up. But other than the sickness and far too much laundry and really only eating bread and butter and saltines, it’s been kind of a nice weekend. There is nothing like being ill to make one appreciate feeling better, and nothing like being ill with 2 small sick children to make one appreciate a spouse who is a partner in every sense of the word—for better or for worse.

The whole thing made me think of the story “Wonder About Parents” from Alexander MacLeod’s collection, Light Lifting. It’s the story about lice, perhaps my favourite in the collection, the one I bring up whenever I’m recalling just how extraordinary that book is. That one scene with the father changing his sick baby’s diaper in the truck stop men’s room, the shit covered baby clothes he tosses into the garbage, and how his wife makes him go back in there and fish it out again. Because she likes that outfit, and it was a gift from her mother. That’s a moment so emblematic of the people parenthood turns us into, the absurdity of these situations. Those nights, those crises. We never think about them when we sign up for any of it.

We could never have imagined. I was thinking about this on Thursday night as I lay in bed sleeping in five minute bursts, interrupted by Harriet throwing up downstairs, Stuart on the floor beside her bed, a pile of soiled sheets and blankets growing up in the corner. I could not sleep because I was hearing strange voices singing, every muscle in my body ached, because I kept having to get up and puke in a bucket, and because I was listening desperately for the sound of Harriet sleeping finally, but she wasn’t. (Her door downstairs just opened now, and its squeak has me wracked with anxiety.) Finally at 3am, I went down because I was finished being sick, and Stuart came up to get some sleep. I was awake until 5am beside Harriet but listening for Iris, who woke up then as usual, and then she was sick. And a new pile of soiled sheets was started in our room. By morning (or at least the part of it when the sun was up), we were all sleeping on top of beach towels, those of us who were sleeping at all.

We could never have imagined. I was thinking about this on Thursday night as I lay in bed sleeping in five minute bursts, interrupted by Harriet throwing up downstairs, Stuart on the floor beside her bed, a pile of soiled sheets and blankets growing up in the corner. I could not sleep because I was hearing strange voices singing, every muscle in my body ached, because I kept having to get up and puke in a bucket, and because I was listening desperately for the sound of Harriet sleeping finally, but she wasn’t. (Her door downstairs just opened now, and its squeak has me wracked with anxiety.) Finally at 3am, I went down because I was finished being sick, and Stuart came up to get some sleep. I was awake until 5am beside Harriet but listening for Iris, who woke up then as usual, and then she was sick. And a new pile of soiled sheets was started in our room. By morning (or at least the part of it when the sun was up), we were all sleeping on top of beach towels, those of us who were sleeping at all.

And it occurred to me at several moments throughout that night, that long long night during which the every passing hour brought a little relief because we were that much closer to morning, when I was holding on and holding my bucket as my child cried, thinking, “it really doesn’t get much worse than this.” It occurred to me it had been remarkable luck and not foresight that 12 years ago I’d met a boy on a dance floor who would become a man who’d take such care of our ailing daughter in the middle of the night, who’d spend the following day doing our laundry as I lay listless on the couch, even though he wasn’t feeling so hot himself. How do you ever, ever know? And what fortune that the whole thing worked out anyway. “You can’t tell anything in the beginning… Could go any number of ways.”

“The present tense. Everything happens here,” writes MacLeod in “Wonder About Parents,” and this is what makes the whole thing so mysterious, I think. How did we get from there to here? How did we become this people awash in a sea of vomit, these children wretchedly ill in a way I had no idea people could be ill (and now we even know it’s totally normal. We go through it a couple of times a year now)? If someone had told me about it, I would have speculated the whole thing was unsurvivable. One of oh so many things you think you could never get through, until you do. I am thinking of Maria Mutch’s Know the Night too, and how I never knew just how many minutes there were between midnight and morning until my children born, an unfathomable number. (In Mutch’s book, referring to her partner, she writes of “that ingredient vital for love, which can best be described, I think, as conspiracy,” which I think is part of what I’m getting at here.)

“The present tense. Everything happens here,” writes MacLeod in “Wonder About Parents,” and this is what makes the whole thing so mysterious, I think. How did we get from there to here? How did we become this people awash in a sea of vomit, these children wretchedly ill in a way I had no idea people could be ill (and now we even know it’s totally normal. We go through it a couple of times a year now)? If someone had told me about it, I would have speculated the whole thing was unsurvivable. One of oh so many things you think you could never get through, until you do. I am thinking of Maria Mutch’s Know the Night too, and how I never knew just how many minutes there were between midnight and morning until my children born, an unfathomable number. (In Mutch’s book, referring to her partner, she writes of “that ingredient vital for love, which can best be described, I think, as conspiracy,” which I think is part of what I’m getting at here.)

Everything was always the present tense, which makes it that much harder to understand how it turned into the past. Like the night, it always seemed to be an eternity until it wasn’t anymore. MacLeod writes, “The place where you wait for the next day to come.”

“We get to choose each other, but kids have no say about the nature of their own lives… What are we to these people? Genetics. A story they make up about themselves.” –from “Wonder About Parents”

“Wonder About Parents” is a story whose workings are fascinating, and I would like to write about it in a more in-depth way when I’m not recovering from illness and the loss of 1.5 nights of sleep. Though I also suspect it’s a story whose wonders are mostly firmly grasped from my current state of mind, if not wholly articulated. The story begins with a couple picking nits from another’s heads, their household under siege. “It’s the third week”. There is so much laundry. “Can’t go on forever./ No.”

The fiction is part entomological investigation of the mighty louse. “The history of the world indexed to the life of an insect.” The parasitic relationship between louse and human is vaguely connected to the parent/child relationship, something persistent in the sheer determination of louse to be, related to that of the human, of the human’s drive to reproduce. The force of life also bringing with it death—typhus is transmitted by lice, MacLeod’s narrator tells us, and killed 30 million people after WW1. And then a scene with the family lining up to be inoculated for swine flu, all that hysteria, fights in the line-ups that started at 4 in the morning. What we do for our children, the ridiculous scenarios. How fragile is our safety, but still we all go forth.

And then before the children, achronological, but all still present tense, and fertility struggles. You never do imagine the care with which you might end up examining your vaginal mucous, all for the eventual outcome of sailing on a sea of vomit, tucked into bed beside your finally-sleeping child wishing that you hadn’t bought her a $45 foam mattress (though the vomit would ruin it anyway, so perhaps it was all for the best).

“Desired outcomes. What we want is when we want it. No way to connect where we are and where we were. This is the opposite of everything we’ve ever done before.”

There are the worst nights, hospital visits with babies a bundle in your arms. A reference to the DDT that solved typhus, but dug its way deep into the food chain before anybody noticed. Causing infertility, cancer, miscarriages. “But life adapt. They go on. Become resistant. Completely unaffected by DDT now. Not like us. Trace amounts of it in every person’s blood.”

The baby has kidney disease, “a congenital abnormality.” We’ve seen this girl already in the shower receiving her lice treatment: “A scar on our daughter’s stomach from before.” So we know which way this story will go. But MacLeod leaves us here, in the hospital, the couple only four months into parenthood, and already they’ve entered its darkest places. And how they lean on each other, how they need one another. They are everyone they’ve ever been, squeezed together in an uncomfortable vinyl chair. Wedded to all of human history.

“Darkness in the room. Our baby makes no sound. Only the bulb from the machine now. Inscrutable purple light flashing on the ceiling. Like a discotheque, maybe, or the reflection of an ancient fire in a cave.”

December 15, 2014

All those dreams I saved for rainy days

One day I want to write about how I met Stuart and life properly began, and how all the energy that I’d previously directed toward trying to make people fall in love with me (and despairing when I always failed) became channelled into useful things. I stopped thinking that “Angie” by the Rolling Stones was a really romantic song. Suddenly my eyes were open and I could see the world, and we began travelling together, learning and growing. I spent a long time before that convinced that I wouldn’t really exist until somebody loved me. This was stupid in retrospect, and contrary to all my feminist principles, but my experience has proven that there was some truth to the notion—that I needed somebody. He’s my enabler in the very best way. And because we met when we were 23, we’ve also grown up together, which is an extraordinary thing to share with someone. When we met, our cumulative possessions would fill two backpacks. Which made it pretty easy for us to run away to Asia a year and half after that, and those experiences would cement our relationship. We’d never argued before—there was so much negotiating and learning involved in figuring out how to live together, and in a foreign country at that. But we made it, stronger for the struggles, and at the end of that adventure, we were yearning for home, so we got married, and began the process of making one here in Toronto, and for two years, we had no money and lived off chickpeas and couldn’t afford to take the subway, and were oh so slim. Whenever I think back to that time now, a part of my brain spends a split-second trying to remember where the children were, until I realize the unfathomable fact—they weren’t there. We didn’t know them. And the paradoxical thought that comes with that one—how miraculous that they’re here at all. I read a line in Gilead today that made me nod, the narrator writing to his son: “…it’s your existence I love you for, mainly. Existence seems to me the most remarkable thing that could ever be imagined.” I know precisely what he means, but I feel it toward my children’s father as well. That there is a Stuart in the world—I will never quite stop marvelling at that. And that he wasn’t always in my world, when he seems as much a part of me as my limbs are—how did I ever get around? Which was probably much of what Mike Reno and Ann Wilson were getting at in their hit song “Almost Paradise (Love Theme From Footloose)”, which is a part of the repertoire in every karaoke room I’ve ever sang in. It’s curious really, because there is no place else you ever hear that song, but it is a karaoke mainstay. We sing it every time we go, at my insistence, and Stuart goes along with it. Though we hadn’t been out for karaoke in ages—not since before Iris was born. But on Saturday night we went out after the children were in bed and we celebrated 12 years since the night we met, and we made wonderful, sweet, terrible unmelodious music together, and came home after midnight.

One day I want to write about how I met Stuart and life properly began, and how all the energy that I’d previously directed toward trying to make people fall in love with me (and despairing when I always failed) became channelled into useful things. I stopped thinking that “Angie” by the Rolling Stones was a really romantic song. Suddenly my eyes were open and I could see the world, and we began travelling together, learning and growing. I spent a long time before that convinced that I wouldn’t really exist until somebody loved me. This was stupid in retrospect, and contrary to all my feminist principles, but my experience has proven that there was some truth to the notion—that I needed somebody. He’s my enabler in the very best way. And because we met when we were 23, we’ve also grown up together, which is an extraordinary thing to share with someone. When we met, our cumulative possessions would fill two backpacks. Which made it pretty easy for us to run away to Asia a year and half after that, and those experiences would cement our relationship. We’d never argued before—there was so much negotiating and learning involved in figuring out how to live together, and in a foreign country at that. But we made it, stronger for the struggles, and at the end of that adventure, we were yearning for home, so we got married, and began the process of making one here in Toronto, and for two years, we had no money and lived off chickpeas and couldn’t afford to take the subway, and were oh so slim. Whenever I think back to that time now, a part of my brain spends a split-second trying to remember where the children were, until I realize the unfathomable fact—they weren’t there. We didn’t know them. And the paradoxical thought that comes with that one—how miraculous that they’re here at all. I read a line in Gilead today that made me nod, the narrator writing to his son: “…it’s your existence I love you for, mainly. Existence seems to me the most remarkable thing that could ever be imagined.” I know precisely what he means, but I feel it toward my children’s father as well. That there is a Stuart in the world—I will never quite stop marvelling at that. And that he wasn’t always in my world, when he seems as much a part of me as my limbs are—how did I ever get around? Which was probably much of what Mike Reno and Ann Wilson were getting at in their hit song “Almost Paradise (Love Theme From Footloose)”, which is a part of the repertoire in every karaoke room I’ve ever sang in. It’s curious really, because there is no place else you ever hear that song, but it is a karaoke mainstay. We sing it every time we go, at my insistence, and Stuart goes along with it. Though we hadn’t been out for karaoke in ages—not since before Iris was born. But on Saturday night we went out after the children were in bed and we celebrated 12 years since the night we met, and we made wonderful, sweet, terrible unmelodious music together, and came home after midnight.

December 11, 2014

Alfie’s Christmas

“And then I knew, Tom, that the garden was changing all the time, because nothing stands still, except in our memory.” –from Tom’s Midnight Garden by Philippa Pearce, which we just finished reading tonight

Alfie never gets older. We’ve been reading his books since Harriet was baby, and I love them impossibly. Their stories are as familiar to me as stories from my own family. I know the corners of their house so intimately—the teapots, and the toy teapots, and Flumbo the elephant, and Willesden the consolation prize, and I’ve speculated aplenty about Maureen McNally, whom I suspect is actually a cat-burgler. And speaking of cats, I know that Alfie’s is called Chessie, and I remember when he comforted his friend at Bernard’s birthday party, and how he likes to play This Little Piggie with his baby sister’s pink toes.

Stuart’s aunt gave Harriet and Iris a book voucher for Christmas, and I ordered them a copy of Alfie’s Christmas, which came out last year. And it arrived today and I opened it at once, because this is one Christmas present we’re going to enjoy before Christmas. It’s a lovely simple story of the countdown to Christmas in Alfie’s house, and all his preparations—his advent calendar, and drawings of stars, and songs at school, baking cookies and putting up the tree. Iris is drawn to the book for the cats in the pictures, and as we were reading the book, we’re realized that she’s probably the age of Annie-Rose, precisely (and she similarly gets into boatloads of mischief).

Harriet liked the book too, which I was relieved about, because I’ve been sensing lately that she feels a bit too old for Alfie and his tales. “Isn’t he in nursery school?” she asked me the other day at the library when I’d proposed taking out one of his books. As a Senior Kindergartener, I think she regards consorting with nursery schoolers, even in literature, as kind of insulting. But I think she still does like these books as much as I do—they really are our foundational texts. And the Christmas in this particular volume won her over, so she was totally game.

It makes me sad though to think that someday Alfie might really be outgrown. It’s inevitable, of course, but it’s also kind of lonely—this wonderful world I’ve discovered through her that we won’t get to share anymore.

I feel as though Aflie’s Christmas might be one that lasts though, having taken up residence in our Christmas book box. A book that will be pulled out again every year, a process whose very appeal is nostalgia. And one day we’ll be telling a wholly different version of Iris, pointing at Annie-Rose, “Once upon a time this was you.”

October 6, 2014

Bunk Beds

“Do you remember,” I asked Stuart on Saturday, as we were assembling the bunk beds, the whole room in disarray around us, our baby climbing in and out of the half-built bed frame, placing her life in peril as usual, Harriet making up dance moves in the doorway, “Do you remember when we painted this room?”

“Do you remember,” I asked Stuart on Saturday, as we were assembling the bunk beds, the whole room in disarray around us, our baby climbing in and out of the half-built bed frame, placing her life in peril as usual, Harriet making up dance moves in the doorway, “Do you remember when we painted this room?”

When we moved in, this second bedroom had been blue with brown trim, ugly industrial shelving along one wall painted grey. It was terrible, but I had a soft spot for this room, which was the computer room, and where our books would live. I really had a soft spot for this room because it was going to be our baby’s room, although the baby was still 100% hypothetical. We spoke about the baby to nobody when we painted that room later that summer, but we were thinking about her. The couple in my mind who painted that room were ridiculously, impossibly young.

Although when the baby was born, she didn’t move into her room for almost a year—it was easier to have her upstairs sleeping with us. And then once she started sleeping, we moved her down, moved the books and computer out. We put up colourful curtains and a bright carpet, and those ugly shelves—now white and less ugly—were packed with books and toys. About a year later, we put away the crib and our futon became Harriet’s bed—our futon, which was the first piece of furniture we’re ever bought, just after we got married in 2005 when we were so poor, and it was the cheapest in the store and it would become our living room couch. And it’s been her bed ever since, the perfect size bed for the whole family to assemble on at story time, and it’s been a stage for her theatrical and dance performances, as well as the one piece of furniture that Harriet is permitted to jump on when friends come over (and why is it that any time a friend comes over, they all start jumping on beds?).

We love our apartment. We made the investment of a custom-built kitchen table last winter in order to make our kitchen a more liveable space for us, a space we can use in the long-term. And the next project would be the bunk beds, because we were determined to make it work in this place as a family of four, and it’s not impossible that Iris may one day not be sleeping in a crib at the end of my bed. (In the past week, Iris has slept all night twice. So there is a modicum of hope.) We finally bought the bunk beds last weekend on our way home from an apple orchard, from a somewhat dodgy showroom that was actually a garage on a dingy post-industrial stretch of Finch Avenue. But they had low-priced bunk beds with stairs, which were the bunk beds I wanted. Because one who climbs stairs to her bed is afforded a bit more dignity that she who must make do with a ladder. And it turned out to be legit, because the bunk beds were actually delivered, except that then we had to build them ourselves, which was the entire story of Saturday.

This is one of those “we bought bunk beds to create space” stories that turns into the bunk beds taking up the entire room. Yes, I intended there to be more space between the bunk bed and the window than there actually is, but then it could have been worse—for a few minutes, we were terrified that the drawers inside the staircase would not even have room to open. I guess this is why some people measure their rooms before they buy really large pieces of furniture, but we don’t like to worry about details in our family. The bunk beds have cleared up space on the floor, however, and the drawers in the staircase have enabled us to get rid of the Ikea dresser we built really really badly before we decided not to buy things from Ikea anymore. (Preferring dodgy garage showrooms, obviously.)

Harriet loves her new bed, which she refers to as “my cozy den”. She’ll move to the top bunk when Iris moves in, but for now the entire bed is her ship, and she is the captain, and the stairs are blocked off so Iris can’t climb them, even though the first step is too high for Iris to mount anyway, but if we leave her alone for a minute, she’ll sprout an inch and/or construct a step-stool out of her First 100 Words book. In even better news, Stuart and my marriage seems not only to have survived an entire day spent constructing bunk beds, to have grown stronger from the experience. We only said “fuck” a couple of times, and even had fun. We’ve gotten over our shock at having inadvertently bought the largest piece of furniture on the planet, and we’re pretty happy with it. We look forward to the day when the bunk beds actually do sleep the two children they’re intended for and our bedroom is our own again, though that’s looking a long way into the future, and let’s just take each day as it comes.

Mostly though, I’m just amazed, at how the years pass, and the memories accumulate, and the children grow, and how this house contains so many our stories, like layer upon layer of invisible paper on the walls, and there’s some crazy archeology at work here, scraping the surface to rediscover our ancient civilizations, right down there at the the bottom of it all that stupid happy couple with their yellow walls, and absolutely no idea of what the years would have in store.

April 21, 2014

A Tale for the Time Being

It was during the summer of 2001 that I started flexing the muscles that would soon come to constitute the foundation of my self, by which I mean that I started book buying in earnest, books that weren’t secondhand paperbacks on my course lists. It was a pretty fantastic time to be buying books. I wasn’t worldly enough to be aware of Toronto’s independent bookshop scene, but I lived at Bay and Charles and was pretty thrilled by this huge and marvellous Indigo shop that had opened up around the corner, and around the corner from there was Chapters, another mega-bookshop, and this was back when mega-bookshops actually sold books. You know, I have nostalgia for those days, when I thought Chapters and Indigo were wonderlands. Like the World’s Biggest Bookstore, but with comfy chairs, and no dingy lighting. Plus, that summer I was working on King Street East, and at lunch time, we’d stop in at Nicholas Hoare and Little York Books, and suddenly my paycheques weren’t going so far, but there I was with The Portable Dorothy Parker and Zadie Smith’s White Teeth, and I was this close to being a grown-up person who could buy books whenever she damn well wanted to. It was delicious.

It was during the summer of 2001 that I started flexing the muscles that would soon come to constitute the foundation of my self, by which I mean that I started book buying in earnest, books that weren’t secondhand paperbacks on my course lists. It was a pretty fantastic time to be buying books. I wasn’t worldly enough to be aware of Toronto’s independent bookshop scene, but I lived at Bay and Charles and was pretty thrilled by this huge and marvellous Indigo shop that had opened up around the corner, and around the corner from there was Chapters, another mega-bookshop, and this was back when mega-bookshops actually sold books. You know, I have nostalgia for those days, when I thought Chapters and Indigo were wonderlands. Like the World’s Biggest Bookstore, but with comfy chairs, and no dingy lighting. Plus, that summer I was working on King Street East, and at lunch time, we’d stop in at Nicholas Hoare and Little York Books, and suddenly my paycheques weren’t going so far, but there I was with The Portable Dorothy Parker and Zadie Smith’s White Teeth, and I was this close to being a grown-up person who could buy books whenever she damn well wanted to. It was delicious.

Though I think I got it on sale, Ruth Ozeki’s My Year of Meats. A hardcover on the remainder shelf, and I bought it at the Bloor Street Chapters. (I loved that store. I still resent the clothing store that later took over the space.) It may well have been the first hardcover I’d ever bought in my life, remaindered or otherwise. It was a monumental acquisition, fun, smart and quirky. As with White Teeth, it brought me an awareness that literature was being written right now, which had never occurred to me as I was plugging away at my English BA. That there was literature beyond my course lists, Joseph Conrad, orange paperbacks, and the New Canadian Library. Ruth Ozeki was a revelation.

And so I’ve been happy to be revelling in her wonderful new novel, A Tale for the Time Being. Everybody on earth already read this book last year and it was listed for all kinds of awards, but I only just got to it now, and it’s so wonderful. So full of everything, and there was the part that reminded me of Back to the Future, and the other that reminded me of A Swiftly Tilting Planet. It was heartbreaking, strange and really beautiful. Definitely worthy of all the acclaim.

This week, I also read Hetty Dorval by Ethel Wilson, who I’d never read before, and that was great too. I was inspired to finally pick it up by Theresa Kishkan’s blog post, and it was partly so great to read because I was reading the Persephone edition.

December 18, 2013

Six Months in, four years later

“My mother didn’t tell me much about motherhood, it’s true. She said she couldn’t remember. None of you ever cried, she said vaguely, and then added that she might have got that wrong.” –Rachel Cusk, A Life’s Work

If I hadn’t written it down, I don’t think I would remember the blurry despair of Harriet’s early days. And even having written it down, the images are fractured. (Joan Didion: “You see I still have the scenes, but I no longer perceive myself among those present, no longer could even improvise the dialogue.”) For a while I’ve supposed that it was really not so bad, and that my tendency to dwell (through writing in particular) had magnified the difficulty and my impressions of my own unhappiness. I have thought this especially since Iris came along and we’ve been weathering all the usual bumps in the road. (“Oh yes, this is why we never wanted to have another baby,” we remembered the other night when once again Iris refused to go to sleep, which, while we meant it, was delivered cheerfully, as a joke.)

The must wonderful and terrible thing about having a blog are its archives. They are, quoting Didion again, “Paid passage back to the world out there.” Sometimes the passage is treacherous though, embarrassing, agonizing, that one person (myself!) could have been so stupid. But it is ever illuminating, these glimpses that remind one to keep in mind the unreliability of memory, the mutability of self.

I remembering telling someone that it was not until around seven months in to Harriet’s life that I was happy in our day-to-day life. (This is important. I am someone who is accustomed to being happy in my day-to-day life.) As time I went on, I started to doubt that this had really been the case, particularly because of how easy Iris has fitted into my life, how much I’m enjoying these days which are mostly spent with her napping on me while I read and write. Surely, I thought to myself, it couldn’t have gone on that long. There are photographs of us smiling. I have excellent memories of wonderful days.

But then I went back recently to read my archives about Harriet at six months, curiosity occasioned by Iris having just reached this milestone. There is a picture of me halfway up a ladder at a bookshop, and I so vividly remembered that day. Stuart had taken the day off and his company was so welcome, and I remembering feeling so fat, horrible, and tired, none of which I mentioned in the post (and I remember feeling quite surprised in fact when the photo wasn’t terrible). It was shocking to me that this had been six months along–I’d remembered it being so much sooner. But then time moved a whole lot slower then.

And then my post about Harriet at six-months, which was useful because it reminded me of her Baby Self who is now lost to us entirely (who sucked on her toes, loved the chicken puppet and had eaten the shopping list the week before).

This was followed by: ” It’s so hard. And I don’t think it ever gets easy, but it gets easier. And then harder too, of course, in all new ways, but the whole thing is also totally worth it in a way I’m really beginning to understand now. Only beginning to, though, because it’s an understanding I can’t articulate or even make sense of to myself, and it’s more a steady current inside of me than a feeling at all./ She is delightful, and fascinating, and amazing, and I can’t remember a world in which Harriet was not the centre. Which is not to say that sometimes I don’t wish for a different focus for a little while, but it would always comes back to her anyway. It always does. And it will forever, but how could it not?”

Confession: I now have no idea what I was talking about. Partly because the writing isn’t terribly clear or good, but mostly because “I no longer perceive myself among those present” in these scenes. Who was that woman anyway? Certainly nobody I’ve ever been.

Isn’t it funny that we persist in imagining time as a line, one thing after another, a cumulation. When it is something else entirely, and only the “now” is ever-present, the past itself gone with a poof out behind us and salvaged sometimes when made into a story.

October 6, 2013

The Things I Want to Keep

In our house, there is now a big plastic bin full of clothing that will never fit anyone in our family ever again. “Should we keep any of it?” I wondered yesterday, only because I thought I had an obligation to wonder. In actuality, we don’t have the room to keep anything and I’m so happy about that because it makes answering such questions much easier. But I wonder too if I will always feel this way, feel the urge to discard pieces of our history, like jetsam.

In our house, there is now a big plastic bin full of clothing that will never fit anyone in our family ever again. “Should we keep any of it?” I wondered yesterday, only because I thought I had an obligation to wonder. In actuality, we don’t have the room to keep anything and I’m so happy about that because it makes answering such questions much easier. But I wonder too if I will always feel this way, feel the urge to discard pieces of our history, like jetsam.

I haven’t always felt this way. Twenty years ago, I saved everything, any flower I’d ever received hung and dried on a line strung across my dusty, cluttered bedroom. Like most teenagers, I took great care to completely paper my room walls with ticket stubs, magazine cuttings, and photos. When the Blue Jays won the World Series, I saved that day’s newspaper in a cardboard box. I was born afflicted with nostalgia. (I imagine that I am quite human-seeming in this regard.) I remember listening to Meat Loaf’s “Two out of Three Ain’t Bad” when I was six, and telling my dad how it reminded of me of the old days (when I was three). Everything I ever did from age 16-23 was carefully mucilaged into scrapbooks. But enough time passed and so much was accumulated that eventually I could see the futility of my attempts to save everything that mattered, and also that the consequence of it all was stuff stuff stuff and necessarily room enough to put it in.

So we don’t keep much anymore. I only kept a few of the scrapbooks. I am aided in all this by living in an apartment and not having a basement, and also in that so much stuff now exists online, thereby not requiring room enough at all. My blog is perhaps my most precious repository. But I become overwhelmed even by a large number photos on my phone, deleting all those but the essential because I fear being carried away by too muchness. I hate that there are 18,000 messages in my inbox. Books aside, I feel so much lighter living my life without freight. I have decided to retrieve from that plastic bin the stripy sleeper that both my girls wore home from the hospital when they were born, and the rest will go to charity.

“In fact I no longer value this kind of memento./ I no longer want reminders of what was, what got broken, what got lost, what got wasted./ There was a period… when I thought I did./ A period during which I believed that I could keep people fully present, keep things with me, by preserving their mementos, their “things”, their totems… In theory these mementos serve to bring back the moment./ In fact they serve only to make clear how inadequately I appreciated the moment when it was here.” –Joan Didion, Blue Nights

Nostalgia, I have learned with time, is an affliction that can’t be cured, or fixed with a totem. I will keep that sleeper with me, but it won’t bring the past any less faraway. Already, I cannot believe that anybody that I love was ever small enough to wear it.

We went out for posh sushi for dinner last night, our first time having it since our post-partum sashimi party when Iris was 5 days old. I’ve been awash lately in nostalgia for June, as Iris turns 4 months old and leaves her newborn self behind. June, not so long ago, of course, but forever irretrievable, a time like no other before or since for our family. Such a gentle time indeed, just like I knew it was while it was happening. I have no need to keep anything from that bin full of clothes, but oh, how I want to preserve those memories, those moments. That week I spent lying in bed recovering my c-section, when Stuart brought me all my meals and there were only four people in the world. I can no longer remember what it was like to not be able to get out of bed unassisted, or not to be able to turn over without a great deal of pain. All those memories gone, and I just remember the sashimi party in our room, that posh sushi. That was the night Harriet hung up the laundry, and played with her sticker book we’d just received from my friend Kate. How summer always is, the way you want to bottle it.

I remember Stuart taking Harriet to school in the morning, and then coming home to collapse into bed with Iris and I. I remember this one evening when Iris and Harriet were both asleep, and I sat down and wrote a review of a picture book. I remember reading The Flamethrowers, and Where’d You Go, Bernadette? I remember Harriet scampering up the stairs to crawl into bed with us every morning, and there would be all of us there, everyone I love best on a single mattress, an island in the universe. Stuart ensuring I was stocked with snacks, reading Harriet stories while I breastfed, how I was annoyed to once again be mobile because then I couldn’t read so much any more.

In June, Harriet watched the Winnie the Pooh movie with Zooey Deschanel over and over again, and we floated around our house like sleep-deprived lunatics, singing the “honey honey honey” song and “It’s Pooh! It’s Pooh! Pooh wins the honeypot,” whenever we changed Iris’s diaper and the situation called for it. How we’d be up at 4am laughing hysterically about Vladimir Putin’s relationship with rhythmic gymnast, and saying, “His virile persona….” which was alway hilarious. The afternoons when Stuart would strap on the baby and take the children away, and I’d be blessed with an hour or so of precious aloneness. I remembering leaving the house even–hobbling to the farmer’s market clutching my incision, going out for ice cream, walking to the playground to fetch Harriet from school. Her class’s end of the year picnic and glorious sunshine. The first time we took the baby out for a meal, for lunch on Father’s Day and she didn’t explode. Tremendous kindness from everyone: cards and presents in the post, meals dropped off, baked goods and visits. All this proof that we were connected to the world and that the world is good.

None of this particularly monumental, of significance to no one but me, though I suspect that it might remind you of your own precious memories, you own very best times. These are those memories that don’t dissolve into the blur of every day, though dissolve they someday will, all the same. And so to counter that, I write them down here, preserve them in my way. These are the things that I want to keep.