May 31, 2012

Franklin Stamps

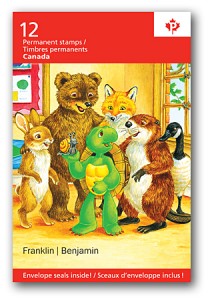

There is not much we love at our house more than we love mail and books (except perhaps for bunting, tea, and train journeys) and it’s always a joy when worlds collide. Yesterday, we picked up a set of Franklin the Turtle stamps at the post office, and we’re in love with them. But they confuse us too, because Harriet thinks they’re stickers and wants to stick them all over her hands and legs, and as for me, I can’t see myself using them anytime soon because then we wouldn’t have them anymore!

There is not much we love at our house more than we love mail and books (except perhaps for bunting, tea, and train journeys) and it’s always a joy when worlds collide. Yesterday, we picked up a set of Franklin the Turtle stamps at the post office, and we’re in love with them. But they confuse us too, because Harriet thinks they’re stickers and wants to stick them all over her hands and legs, and as for me, I can’t see myself using them anytime soon because then we wouldn’t have them anymore!

More about postal goodness: the joy of postcards.

May 17, 2012

Picture books in which animals are put in jail

This is something I’ve been thinking about for some time. It is by no means a comprehensive list.

Curious George by Margret and HA Rey: Early Curious George was not only an avid cigar smoker, but ends up in jail for making prank calls to the fire department. Being a monkey, he is able to escape from jail with relative ease when a prison guard stands on one end of George’s cot whilst chasing him and lifts the other end up to the window. He floats away in a balloon. Later, he stars in a movie.

Curious George by Margret and HA Rey: Early Curious George was not only an avid cigar smoker, but ends up in jail for making prank calls to the fire department. Being a monkey, he is able to escape from jail with relative ease when a prison guard stands on one end of George’s cot whilst chasing him and lifts the other end up to the window. He floats away in a balloon. Later, he stars in a movie.

Veronica by Roger Duvoisin: Veronica is a hippo who hates to blend into her herd (whose collective noun is actually “bloat”, but this isn’t part of the text). She gets around her camoflage by escaping to the city, but the gets hauled away for holding up traffic. The jail, unfortunately, barely contains her (speaking of bloat), and they have to bust down the doors to get her out of the place after a sympathetic little old lady comes to her aid and wins her freedom.

Chouchou by Francoise: Chouchou is a little French donkey who leads a simple but pleasant life having tourists pose with her for photographs. One day while provoked, however, she bites a young customer and is thrown in jail. She is only freed once the local children attest to her gentleness, demonstrating to officials that she’s indeed a harmless creature. She is freed in time to officiate at her photographer-owner’s wedding.

Chouchou by Francoise: Chouchou is a little French donkey who leads a simple but pleasant life having tourists pose with her for photographs. One day while provoked, however, she bites a young customer and is thrown in jail. She is only freed once the local children attest to her gentleness, demonstrating to officials that she’s indeed a harmless creature. She is freed in time to officiate at her photographer-owner’s wedding.

May 11, 2012

In which I help solve a literary mystery I unwittingly created

1) Dear Ms. Clare, I recently signed out a copy of Lionel Shriver’s The Post-Birthday World from the Toronto Public Library and found it inscribed, “Kerry Clare, March 2007,” as well as with a hand-written “To Kerry” and an illegible signature on the title page. I did some Googling and saw that you reviewed this book on your blog in March, 2007. So this must be “your” copy of the book, right? I’m just wondering why a library book might have your name in it! And possibly the author’s signature, too?

1) Dear Ms. Clare, I recently signed out a copy of Lionel Shriver’s The Post-Birthday World from the Toronto Public Library and found it inscribed, “Kerry Clare, March 2007,” as well as with a hand-written “To Kerry” and an illegible signature on the title page. I did some Googling and saw that you reviewed this book on your blog in March, 2007. So this must be “your” copy of the book, right? I’m just wondering why a library book might have your name in it! And possibly the author’s signature, too?

Hoping you’ll be willing to provide an explanation, I remain

A curious fellow reader (who is, incidentally, enjoying the book very much),

Kyle Miller

Toronto

2) Wow, I gave away an autographed book? That wasn’t so clever. I did see Lionel Shriver at HarbourFront in 2007 and she was wonderful. But I have far too many books in my life, and regularly prune my collection, donating the discards to the Spadina Road Library, which is one of the best places I know. If I’d realized it was autographed, I probably would have kept the book. But then I love a good literary mystery as much as the next guy, and I’m pleased to have been a part of one, so I’m glad I didn’t.

2) Wow, I gave away an autographed book? That wasn’t so clever. I did see Lionel Shriver at HarbourFront in 2007 and she was wonderful. But I have far too many books in my life, and regularly prune my collection, donating the discards to the Spadina Road Library, which is one of the best places I know. If I’d realized it was autographed, I probably would have kept the book. But then I love a good literary mystery as much as the next guy, and I’m pleased to have been a part of one, so I’m glad I didn’t.

Can I post your message on my blog? My blog is all about literary connections, and this is perfect.

Thanks for writing. I’m glad you’re liking the book. I liked it too, as my review attests.

All the best to you,

Kerry

May 1, 2012

The new bunting is here.

I know you’ve been waiting on tenterhooks, but no longer: the new bunting is here! The bad news about this is that no longer are we awaiting bunting in the post, which is a glorious state of being, but at least we get to have our bunting and hang it too. The new bunting was purchased to replace the old bunting, which I’d handmade from origami paper, scotch-tape and a piece of yarn, and was in a rather sorry state. For the new bunting, we went upscale and outsourced it from one with my craft skills than have I. And I’m totally in love with it, just as expected. No longer do we have shabby bunting to be ashamed of, and the best part of the bunting life, of course, is that each day is a celebration.

I know you’ve been waiting on tenterhooks, but no longer: the new bunting is here! The bad news about this is that no longer are we awaiting bunting in the post, which is a glorious state of being, but at least we get to have our bunting and hang it too. The new bunting was purchased to replace the old bunting, which I’d handmade from origami paper, scotch-tape and a piece of yarn, and was in a rather sorry state. For the new bunting, we went upscale and outsourced it from one with my craft skills than have I. And I’m totally in love with it, just as expected. No longer do we have shabby bunting to be ashamed of, and the best part of the bunting life, of course, is that each day is a celebration.

January 24, 2012

The sense of a story

Last summer, Los Angeles Times columnist Meaghan Daum wrote about Jaycee Dugard and her story spun as a redemption narrative: “I detect a need on the part of the media to wrap her story up in a bow, to assure the public that she’s OK, to reinforce the central narrative of just about everything we see on TV: Change is possible, maybe even easy; that adversity can be overcome; and that, as Dr. Phil likes to say, there are no victims, only volunteers.” When I read Daum’s piece, I couldn’t help but think of US Representative Gabrielle Giffords and the expectations that have been foisted upon her since her injuries last January, perhaps perpetuated by the very fact that she’d survived being shot in the face in the first place.

Last summer, Los Angeles Times columnist Meaghan Daum wrote about Jaycee Dugard and her story spun as a redemption narrative: “I detect a need on the part of the media to wrap her story up in a bow, to assure the public that she’s OK, to reinforce the central narrative of just about everything we see on TV: Change is possible, maybe even easy; that adversity can be overcome; and that, as Dr. Phil likes to say, there are no victims, only volunteers.” When I read Daum’s piece, I couldn’t help but think of US Representative Gabrielle Giffords and the expectations that have been foisted upon her since her injuries last January, perhaps perpetuated by the very fact that she’d survived being shot in the face in the first place.

The narrative of her “recovery” though has been so remarkable for its falseness, for its abject denial of the realities of brain injury. Which can’t be wholly blamed on the media, I realize, because Giffords and her publicity team appear to have been much in command of her image over the past year, though I suppose theirs has been a fair response to having to endure what Giffords has in the public eye. If I were Giffords, I would want my audio edited too, my photos carefully posed, my dignity preserved, but this doesn’t change the fact of what many of us can read between the lines: that her story is a tragedy without meaning, without redemption. The miracle is that she’s still here at all, but she’s being pressed to make it more than that.

“Most art is more a matter of finding a few meaningful moments in an utterly plotless flow,” writes Rick Salutin in a recent column “Why the storytelling model doesn’t work.” He notes how inapplicable is story as a model in most kinds of culture, let alone as a metaphor for “Life Itself”. That we usually demand more than mere story from our greatest art, and yet journalists are still required to fit their own work into tidy story-sized packages (and tied with Meaghan Daum’s bow), distorting how the rest of us perceive the world around us.

All of which is true, of course, which doesn’t sit terribly well with me who has lived life so far turned to the novel in place of religion. How to reconcile this? Would the novel telling of Gabrielle Giffords’ story diverge sharply from the shape of a Diane Sawyer interview? Though I keep thinking that maybe story isn’t what Salutin has a problem with per se, but rather that he has a narrow definition of what story is, of its mereness. That perhaps the problem remains, as ever, with the tidy ending, with satisfying that yearning for redemption, both of which are actually a failure to acknowledge the way that story really works, and Life Itself for that matter. (And the simplest solution to this problem is the short story, but you already knew that.)

Penelope Lively’s latest novel How It All Began makes the case for story as Life Itself. Story, her characters remark, is forward-motion, one thing after another, driven by the reader who wants to see what happens next. “Narrative. But a contrivance– a clever contrivance if successful.” Real life, her characters acknowledge, is different from “the unruly world in which we have to live. One’s unreliable progress.” And yet Lively is putting these words in the mouths of her fictional characters to make the point that the novel (and art in general) is actually capable of assuming the shape of reality. That in both life and in art, we must make our way by investing happenstance with meaning after the fact. That story is simultaneously more simple and more complex than how we commonly perceive it, but that it’s only a useful tool when we understand that it’s a tool after all.

Update: I’m reading Skippy Dies, and just came across the passage, “…stories are different from the truth. The truth is messy and chaotic and all over the place. Often it just doesn’t make sense. Stories make things make sense, but the way they do that is to leave out anything that doesn’t fit. And often that is quite a lot.” But as with the Lively book, here is a novel that creates that sense of messy chaos. I don’t think it’s time to give up on story just yet.

Update to update: It occurs to me that I’m 550 pages into Skippy Dies, and that if there is no redemption by the book’s end, I am going to be very dissatisfied. That 600 pages of messy chaos is a mindfuck, and I really do feel like there has to be some kind of pay-off. So perhaps I shouldn’t situate myself too far away from the Dr. Phil-loving masses.

January 22, 2012

"Loving the mayor is a bit like that": Rosemary Aubert's Firebrand

Rosemary Aubert’s Firebrand is a Harlequin SuperRomance published in 1986, and that I discovered it via a footnote in Amy Lavender Harris’s Imagining Toronto is to give you an indication that Harris’ book is chock-full of fascinating stuff. As is Firebrand, actually, which I would bet is the only Harlequin ever whose romantic lead has a painting of William Lyon MacKenzie on his office wall. This is a Toronto book through and through, dedicated, “To T.O, I love you,” and it shows.

Rosemary Aubert’s Firebrand is a Harlequin SuperRomance published in 1986, and that I discovered it via a footnote in Amy Lavender Harris’s Imagining Toronto is to give you an indication that Harris’ book is chock-full of fascinating stuff. As is Firebrand, actually, which I would bet is the only Harlequin ever whose romantic lead has a painting of William Lyon MacKenzie on his office wall. This is a Toronto book through and through, dedicated, “To T.O, I love you,” and it shows.

It’s the story of Jenn McDonald, unassuming librarian (naturally), but she’s an unassuming librarian at the Municipal Affairs Library at Toronto City Hall (which, under our current city government, has been made to no longer exist). Which gives her a good vantage point from which to observe the city’s mayor Mike Massey (whose not one of those Masseys, the novel tells us), who Jenn remembers from the days when he was a rebellious young alderman and the two of them spent a memorable night together locked up in a police station after a protest.

When they meet again while watching the ice-skaters at Nathan Phillips Square, their original spark is rekindled and Jenn and Mike are drawn to one another. She is baffled by his desire, a man so far out of her league, but it turns out that he’s attracted to her down-to-earth qualities and her spirit, and as they argue about developing Toronto’s portlands and the preservation of the Leslie Street Spit, he can see that she’s a woman who can more than hold her own.

But loving the mayor isn’t all posh cars and white roses. It’s hard to love a man who’s already married to his job, and who is used to commanding all those around him. The path to true love doesn’t quite run smooth, and its bumps include a fierce debate on city council about Toronto police officers being armed with machine guns (Mike Massey is firmly against; his stance is unpopular at a time when officers are being shot with Uzis), Jenn receiving death threats, a custody battle with Mike’s ex-wife, and Jenn’s unresolved feelings with her husband. All this against a fabulous Toronto backdrop: first dates in Chinatown, their homes on either side of the Don Valley (with the footpath between them), Jenn shopping at the Room at Simpsons, galas at the King Edward, a protest near OCAD against arts cuts (including those funding The Friendly Giant, we are subtly told), a stroll together through the Moore Park Ravine, a political rally at the Palais Royal. Michael Ondaatje might own the literary Bloor Street Viaduct, but he’s got nothing on Rosemary Aubert for the rest of town.

It’s really quite a good book. This surprised me, though there are some who will rush to tell me that we all write off Harlequins too quickly, but I’m still pretty sure they’re not my thing. Because this book is a Harlequin, there are passages like, “Whispering, caressing, clutching, they continued, until Mike’s large, warm, immensely masculine body covered Jenn’s completely. Until the soft, shifting eagerness of her beneath him brought him to the brink of ecstasy. He asked. She answered yes. Oh yes.”

And then later in the mayor’s office: “Before her, all six-foot-four of him glowing in the soft window light, stood Mike, fully and gloriously a man. Hungry for her with a hunger that was obvious in every part of his huge body.” Which makes “300 pounds of fun” seem kind of paltry, no?

So there’s that, but aside from huge bodies, Aubert paints the city of Toronto with a vibrant specificity, and anyone who cares about our city’s literature (and municipal politics!) should definitely check out this book. The very best part of Amy Lavender Harris’ Imagining Toronto is its challenge of every prejudice as to what Toronto Literature comprises– the canon is more surprising than you ever imagined. And how fortunate we are that Harris’ book turns up Firebrand, which is out of print, hardly known, and hasn’t a single copy held by the Toronto Public Library. I would urge you to pick up your used copy on Amazon for a penny like I did while there are still copies out there to be had.

January 14, 2012

Rambling among the trees

“The purpose of this bulletin is to make it easier for people to become personally acquainted with our trees. It is believed that the securing of the interest of the people of the province in trees will be an aid toward an understanding of the importance to us of our forests, and thus pave the way for support of forestry principles.” –J.H. White, Toronto 1925

“The purpose of this bulletin is to make it easier for people to become personally acquainted with our trees. It is believed that the securing of the interest of the people of the province in trees will be an aid toward an understanding of the importance to us of our forests, and thus pave the way for support of forestry principles.” –J.H. White, Toronto 1925

Which is from the preface to The Forest Trees of Ontario (1957 edition) which I found last winter in a cardboard box on Major Street and took home even though it smells like a basement. I love this book, though I confess I don’t know a papaw from a sassafras.

“When I’m in Toronto, I always drop in at the Monkey’s Paw Bookstore. Stephen Fowler, the owner, has an  incredible eye. (I recently came back with a book of transcribed seance sessions, a history of women in uniform, a treatise on baking, and a book of party games for adults.) He had this book called the Native Trees of Canada displayed on a table. I flipped through it, and I immediately knew I needed to buy it. It was a government volume: unmediated and strictly informational. It was filled with very sterile, black and white pictures of leaves, placed on a grid for scale. While looking at them, I had vivid memories of picking at maple seeds on my front lawn, of wet leaves stuck to my shoes, of fallen leaves blowing through the screen door. I knew I wanted to paint them. “– Leanne Shapton, “The Native Trees of Canada”, Paris Review Blog, November 2010

incredible eye. (I recently came back with a book of transcribed seance sessions, a history of women in uniform, a treatise on baking, and a book of party games for adults.) He had this book called the Native Trees of Canada displayed on a table. I flipped through it, and I immediately knew I needed to buy it. It was a government volume: unmediated and strictly informational. It was filled with very sterile, black and white pictures of leaves, placed on a grid for scale. While looking at them, I had vivid memories of picking at maple seeds on my front lawn, of wet leaves stuck to my shoes, of fallen leaves blowing through the screen door. I knew I wanted to paint them. “– Leanne Shapton, “The Native Trees of Canada”, Paris Review Blog, November 2010

Leanne’s Shapton’s book of paintings is Native Trees of Canada and it’s beautiful. And if there are two of us out there appreciating these old government-issued volumes, there are bound to be more. Which gives me faith in the world, actually, in readers and books, and the trees whose lives were given so that we can read pages. (Even old ones that smell like basements.)

Leanne’s Shapton’s book of paintings is Native Trees of Canada and it’s beautiful. And if there are two of us out there appreciating these old government-issued volumes, there are bound to be more. Which gives me faith in the world, actually, in readers and books, and the trees whose lives were given so that we can read pages. (Even old ones that smell like basements.)

Also, I have also discovered that the maple in our backyard is a black maple.

(See also my Tree Books list at Canadian Bookshelf, whose compilation brought Shapton’s book to my attention in the first place.)

“It is hoped that the bulletin will combine instruction with recreation for all who care to go rambling among the trees.” –J.H. White

January 11, 2012

The Canadian Publisher as "important component of civilization"

Here’s what sprang to my mind when I heard about Random House’s takeover of McClelland & Stewart:

“I arrive in Toronto on the day that Coach House Press goes out of business. (Coach House’s recent revival could not be foreseen at the time.) More startling than Coach House’s death is the reaction to its demise. Where past politicians, even those ill-disposed towards the cultural sector, would have felt it expedient to play lip-service to Coach House’s achievements, Ontario Premier Mike Harris launched into an attack on the press’s ‘history of total government dependence.’ Though Harris’ characterization isn’t strictly accurate, I am struck by how many of the writers and commentators who respond to Harris argue from the same set of assumptions: they defend Coach House’s accounting and marketing strategies, arguing for the press as a viable business rather than an important component of a civilization… Canadian public debate has changed in ways that make it increasingly difficult to justify, or even imagine, the sense of collective endeavour that fuelled the writing community only a few years earlier.” –Stephen Henighan, “Between Postcolonialism and Globalization”

(As you can see, I got a lot out of Henighan’s book, which I picked up just after the death of Josef Skvorecky, whose work he addesses in the essay “Canadian Cultural Cringe” and which certainly provided a counterpoint to the Skvorecky obits. And then this Random House news yesterday afternoon. Seems Henighan’s ideas are very relevant at the moment.)

December 8, 2011

Virginia Lee Burton and the Graphic Novel

I’ve enjoyed Virginia Lee Burton’s books for as long as I can remember, though never more than I have in the past year as I’ve come to understand her approach to book design (and how far-reaching was her influence). Anyway, last weekend our friend Aaron picked our copy of Katy and the Big Snow, which has no dust cover because Harriet has declared it her mission to rid books the world over of their dust jackets (plus the jacket was already battered– this was a discarded library book we bought for a quarter. Jacket has been put away to avoid further battering).

I’ve enjoyed Virginia Lee Burton’s books for as long as I can remember, though never more than I have in the past year as I’ve come to understand her approach to book design (and how far-reaching was her influence). Anyway, last weekend our friend Aaron picked our copy of Katy and the Big Snow, which has no dust cover because Harriet has declared it her mission to rid books the world over of their dust jackets (plus the jacket was already battered– this was a discarded library book we bought for a quarter. Jacket has been put away to avoid further battering).

And Aaron said, “Don’t you think this looks like something by Seth?” And we thought,  “Hey, he’s right,” of course. And because I know very little about Seth or about cartooning, I did a bit of googling, and found this blog post from Drawn & Quarterly entitled “Virgina Lee Burton: Godmother of the Graphic Novel.” So goes the post:

“Hey, he’s right,” of course. And because I know very little about Seth or about cartooning, I did a bit of googling, and found this blog post from Drawn & Quarterly entitled “Virgina Lee Burton: Godmother of the Graphic Novel.” So goes the post:

I always find it curious when people draw distinctions between kids comics and kids picture books, basically you’re telling stories with pictures in both instances, and the art can’t be separated from the words. Why is Sara Varon’s Robot Dreams a comic, while Chicken and Cat is not? And really, aren’t graphic novels just pictures books for adults. Semantics, I know.

The post is referring to a slide show with the “Godmother of the Graphic Novel” title presented by cartoonist James Sturm. The site it was published on seems no longer current, and the slideshow itself isn’t functional, which is driving me crazy, because I want to see it so badly! I’ve scoured the internet for Sturm’s contact info, but no dice. So I’m disappointed, but also excited that the importance of Virginia Lee Burton might be greater than I’ve imagined yet.

November 14, 2011

This is where we used to live.

2001/2002 was my final year at university, the year I had a back page column in the school newspaper and therefore had a platform from which to address the question of what it meant to live on a “grimy, yet potentially hip strip of Dundas St. West”, as my block had been described by the Toronto Star in a restaurant review of Musa. To live on such a strip meant kisses in doorways, I wrote, because no boy would ever let you walk home alone, it meant watching from your bedroom window as a dog devoured a skunk, and having to call the police when people started smashing car windows with implements from the community garden. I can’t remember what else I wrote in that piece, and Musa burned down two summers ago, but neither point means that year is lost. I have never gotten over it.

2001/2002 was my final year at university, the year I had a back page column in the school newspaper and therefore had a platform from which to address the question of what it meant to live on a “grimy, yet potentially hip strip of Dundas St. West”, as my block had been described by the Toronto Star in a restaurant review of Musa. To live on such a strip meant kisses in doorways, I wrote, because no boy would ever let you walk home alone, it meant watching from your bedroom window as a dog devoured a skunk, and having to call the police when people started smashing car windows with implements from the community garden. I can’t remember what else I wrote in that piece, and Musa burned down two summers ago, but neither point means that year is lost. I have never gotten over it.

Everything felt monumental that year, not because of anything specific, although it was our final year of school, and 9/11 occurred days into it, serving to make us think a lot about things we’d always before taken for granted. “That was a year,” wrote my friend Kate in a recent email, “we all made enormous leaps into adulthood even if many days it felt like we were just playing.” And of course, everybody has had those years, monumental if only for how they delivered us to here. A threshold to something finally real, but we were aware of it happening all the time, and so amazed to watch the world opening up before our eyes.

And so it felt entirely appropriate when I discovered last week that they’d turned our entire apartment into an art exhibition. (It all feels a bit Tracey Emin.) “They” being the people at Made Toronto, which now lives downstairs from where we used to live, though that storefront was a Chinese herb shop when it was ours. (It was a different time. We’d never heard of hipsters, and Musa was the only place to get brunch for blocks and blocks. David Miller wasn’t even the mayor then, and Spacing Magazine had yet to be invented.) The exhibition took place last year, designer furniture and housewares on display in a “typical Toronto apartment,” which is funny because there was nothing typical about it– for about nine months that I know of, that apartment was the centre of the universe. It’s also funny because it’s the ugliest apartment I have ever, ever seen. Aesthetically speaking (although “aesthetic” was not, in fact, a word I was aware of when I lived there), that apartment’s sole redeeming feature was the patio where I used to go to pretend to smoke cigarettes, and watch the city skyline.

Part of the reason I love my husband is because I brought him home for a visit from England in 2003 when the apartment was still inhabited by friends of mine. And they had a party to welcome me back, and so for two days, he got to know almost exactly what I was talking about when I talked about that place, about that time. I love that he was there, that brief intersection between my new life and my old one. I love that my roommates are still such dear friends, no matter that we live so far apart now. And I love that the hideous pink linoleum floors are just the same, and that we’ve come so far, they’re considered art now.