February 1, 2010

Meet the Smiths

I’ve got a family of Smiths on my bookshelf. Probably you do too. Mine are diverse but an excellently harmonious bunch. There’s Ali, of course, of The Accidental and Girl Meets Boy. And then Alison, of the poetry collection Six Mats and One Year. Next is Betty, who wrote A Tree Grows in Brooklyn. Beside her is Ray, then Russell, and Zadie, who have brought to the library Century, Muriella Pent and White Teeth/On Beauty, respectively.

This is the largest clan in my library, save for the Mitfords who don’t actually count because they’re really sisters. And I’m not sure if this bunch is alike or unhappy in their own way, but I like how their jackets rub together anyway.

January 30, 2010

Raise high the roofbeam carpenters

Phoebe Caulfield was Holden’s nine-year old sister, plucky as a red-headed orphan, just lacking appropriate pigmentation and tragedy. Even Holden would affirm that, “if you don’t think she’s smart, you’re mad.”

Pheobe was a writer, composing the stories of “Hazel Weatherfield” in her multiple notebooks. As an actor, she was ecstatic to have the largest part in her class play, even if it involved playing Benedict Arnold. “Elephants knock[ed] her out.” Phoebe Caulfield was a force to be reckoned with, pouring ink down the windbreaker of anyone who dare cross her path and she could recite Robbie Burns on command.

She was also a realist. While her brother Holden tried to deny his bleak reality, Phoebe made a point of thrusting the thing in his face. Not allowing him the luxury of his skewed perspective, sick of tirades about phoniness, she says bluntly, “You don’t like anything.” In contrast, Pheobe herself was able to make the best of her difficulties. Holden’s drunken shattering of record he’d bought for her failed to hinder her enthusiasm for the gift: “‘Gimme the pieces,’ she said. ‘I’m saving them.'”

A beacon in her brother’s lonely existence, Phoebe’s love makes clear Holden’s real emotional capacity and the depth of his troubles. Upon learning that he’d been expelled from yet another school, hers is the first display of genuine, grounded concern anyone shows him. Her maturity outmatches Holden’s, and his tender feelings towards her highlight his own vulnerability.

In Phoebe, Holden also sees the innocence he has lost, but elsewhere in Salinger’s oeuvre is evidence that Phoebe Caulfield was wise rather than naive, and that her wisdom beyond her years (“Old Phoebe”) might never have disappeared. I like to think that if Salinger had continued the saga of the Caulfield family, Phoebe would have grown up to be someone much like Boo Boo Glass.

Of course, the details of Salinger’s salacious personal life widely reported him as something of a letch, and his stories contain their share of one-dimensional female characters. But he knew something about women, or perhaps something about sisters is more what I mean.

Boo-Boo appears in the background of Salinger’s Franny and Zooey and Raise High the Roofbeam Carpenters. She also makes an appearance in “Down at the Dinghy” from Nine Stories, in which “[h]er general unprettiness aside,” writes Salinger, “she was a stunning and final girl.” Ever capable, Boo-Boo flew with the Woman’s Air Force in World War Two, bravely tackled anti-Semitism in her marriage to a Jewish man, and mothered her young son with the same insightful sensitivity Phoebe provides to her brother Holden.

In a tortured world of Seymour and perfect days for bananafish, Boo-Boo stands on the side of justice, for all things bright and good, however much in vain. And I am insistent upon optimism, so for me, it is her spirit that pervades Salinger’s best writing and makes me love it so. Her presence in Raise High the Roofbeam Carpenters consists solely of a note left on the bathroom mirror of her brothers’ New York apartment. “‘Raise high the roofbeam carpenters… Please be happy happy happy. This is an order. I outrank everyone on the block.”

(an earlier version of this piece appeared in the independent weekly on September 6 2001.)

January 27, 2010

Family Literacy Recommendations from a Literary Dad: George Murray

George Murray’s new book Glimpse: Selected Aphorisms will be published this fall by ECW Press. His other books of poetry include The Rush to Here (Nightwood, 2007), and The Hunter (McClelland & Stewart, 2003). He lives in St. John’s, Newfoundland is the editor of Bookninja.com.

George Murray’s new book Glimpse: Selected Aphorisms will be published this fall by ECW Press. His other books of poetry include The Rush to Here (Nightwood, 2007), and The Hunter (McClelland & Stewart, 2003). He lives in St. John’s, Newfoundland is the editor of Bookninja.com.

He shared his best bets for books to read together as a family:

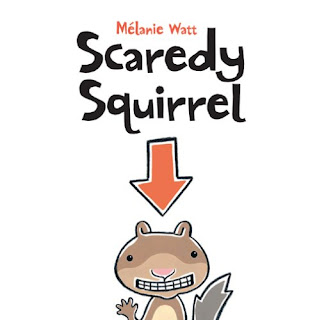

My boys are five years apart, so it’s hard to find books they’ll enjoy  together. The older one (seven) loves fantasy stories (like those by Kate DiCamillo) and is a precocious reader, while the younger (almost two) loves rhythmic rhyming books and bright pictures of animals (Hands, Hands, Fingers, Thumb, etc). So in between those two, I’d recommend Scaredy Squirrel books by Melanie Watt. The baby likes the pictures and pace and the boy likes the jokes and nuttiness (pun intended). Watt’s a fabulous writer and a delightful illustrator and I often find myself chuckling as well… At least the first 100 times or so…

together. The older one (seven) loves fantasy stories (like those by Kate DiCamillo) and is a precocious reader, while the younger (almost two) loves rhythmic rhyming books and bright pictures of animals (Hands, Hands, Fingers, Thumb, etc). So in between those two, I’d recommend Scaredy Squirrel books by Melanie Watt. The baby likes the pictures and pace and the boy likes the jokes and nuttiness (pun intended). Watt’s a fabulous writer and a delightful illustrator and I often find myself chuckling as well… At least the first 100 times or so…

January 27, 2010

Our Family Literacy Day Baby Literary Salon

It’s Family Literacy Day! To celebrate, we invited our favourite Mom and Baby friends to share some stories, and to sing some songs (as the theme of this year’s Family Literacy Day is “Sing For Literacy”). The event was a resounding success, and not just because of the snacks provided. No, it was a success because the guests brought even more snacks, including delicious fudge, green tea shortbread and jello treats for the little ones. (Forgive me for fixating on edibles, but for breastfeeding women, this is very very important).

Margaret and her mom Carolyn brought family favourite Tumble Bumble, as well as Margaret’s beloved book of the moment Boo Boo. Finn in particular enjoyed Tumble Bumble. His mom Sara came with a copy of one of her childhood favourites, the absolutely magical The Bed Book by Sylvia Plath. Who knew Sylvia Plath wrote a children’s book? No, not I. But I liked the elephant bed the very best.

Leo’s mom Alex brought along a copy of hardcore alphabet book Awake to Nap by Nikki McClure. The illustrations were beautiful, and “I is for inside” was the best one. Later, Alex read Margaret Atwood’s first kids’ book Up in a Tree, which was pretty delightful and might even impress the most avid Atwood-hater. Also remarkable was the character that looked like a baby Margaret Atwood, and was absolutely adorable.

I read Ten Little Fingers Ten Little Toes, as well as Harriet’s fave All About Me: A Baby’s Guide to Babies. And then, because of the singsong theme, we also read/sang Old MacDonald, Five Little Ducks and The Wheels on the Bus. The babies played quite happily together, and took turns playing with the best toy out of all the toys we own: a tin pie plate. Harriet fell down from sitting and now has her first bruise. Leo and Finn bonded over a set of plastic rings. Margaret showed us her mobility prowess. We listened to Elizabeth Mitchell, and drank tea, and ate delicious things, and in celebrating family literacy, we spent a splendid afternoon.

January 22, 2010

An admission and some understanding

I have an admission to make, one that will win me no friends. And while usually I do not knock the books I hate here, this book is so well-loved, I think it can take it. I HATE The Number One Ladies Detective Agency. I got this book free out of a cereal box in 2003 (true story!), and have received it as a gift no less than three times since then. I read it once and found it so boring, I found it offensive, not credible as literature. And I know this will rankle many a reader now, because people love Precious Ramotswe and Alexander McCall Smith, but for the life of me, I could never undertand why.

Until now. I get it now! I still hate The Number One Ladies Detective Agency, but I think my love of Flavia de Luce and The Sweetness at the Bottom of the Pie is analogous to how other readers must feel about Precious and Number One… And not just because they’re both books with colonial flavour, written by old white men in unlikely voices (whether they be those of Botswanan lady detectives, or eleven year-old English girls). I think neither book is meant to ring especially true, authenticity is not the object, that these books get by on their charm, and charming is most definitely in the eye of the beholder.

Stay tuned for a review of Sweetness at the Bottom of the Pie from the perspective of this beholder. I loved that book indeed.

January 22, 2010

Escape the ego

I was surprised to be impressed by Elizabeth Gilbert in her recent Chatelaine interview. I am one of those irritating people who has never read Eat Pray Love but holds strong opinions about it anyway, so the interview was the first time I’d ever been exposed to Gilbert directly (as opposed to via one of her ardent devotees). She seemed terrifically level-headed about the impact of her book upon her fans, noting that readers who’d decided to follow in her eating, praying, loving footsteps were probably insane. She had smart things to say about women and their expectations for relationships, for happiness. But what I noted most of all was the following: “I don’t think women today read for escape; they read for clues.”

I loved that. Because it’s exactly the way I read, I think, to break it down and enable me to see the world in miniature, as manageable. Which, however conversely, is to be able to look at the big picture and regard it all at once, perhaps for the very first time. Fiction is a study in the hypothetical, a test-run for the actual. An experiment. What if the world was this? And we can watch the wheels turn and this bit of sample life run its course to discover. And I don’t mean that literature is smaller than life, no. Literature is life, but it’s just life you can hold in your hand, stick in your backpack, and I’m reassured by that, because the world is messy and sprawling, but if you take it down to the level of story, I am capable of some kind of grasp. Of beginning to understand what this world is, how to be in it. Certainly, I read for clues.

But then Elizabeth Gilbert went and ruined the whole thing, continuing, “The criticism of memoirs is that people read them to be voyeurs. But a lot of people read them for help and answers and perspective.” So she wasn’t actually talking about fiction, which takes the wind of out of my sails, and now she’s relegated reading in general to the self-help rack. Which is boring, troubling, limiting. So there ends my love affair with Elizabeth Gilbert, perhaps because I’m skeptical of memoirs and the kind of truth any reader might hope to find there.

And then I came across this video of Fran Lebowitz on Jane Austen (who Lebowitz says is popular for all the wrong reasons). Lebowitz says, “To lose yourself in a book is the desire of the bookworm, to be taken. And that’s my desire… [which] may come from childhood. The discovery of the world, which I discovered in a library– I lived in a little town and the library was the world. This is the opposite way that people are taught to read now. People are consistently told, ‘What can you learn about your own life from the novel?’ ‘What lessons will this teach you?’ ‘How can you use this?’ This is a philistine idea, this is beyond vulgar, and I think this is it is an awful away to approach anything… A book is not supposed to be a mirror. It’s supposed to be a door.”

Which was something I could get behind. I was finished with Elizabeth Gilbert, and was about to jump on the Fran Lebowitz reading-wagon, when it occured to me, “To lose yourself in a book is the desire of the bookworm, to be taken.” And is that not the very definition of “escape”? Escapism, which is all about stupid women reading pink shoe novels on the beach, with Fran Lebowitz alongside them? I couldn’t see it.

But escapism is surely what she’s advocating, however much “the world” is what she is escaping to. And it occurs to me that Elizabeth Gilbert’s clue-seeking readers are escapists just as much, however in a far more literal sense. That they’re plotting a way out of their humdrum lives, just as Lebowitz was doing back at that small town library. Searching for different kind of place for themselves.

Do I read for escape? I don’t know. Does reading for fun count as escape? Does reading to relax? Interestingly, the books I’d read for fun or relaxation are those that would make me “lose myself” the least, which would make them the least escapist of all. I just finished The Sweetness at the Bottom of the Pie, for example, which was fun and fluffy as you like, but Century is a book that’s more taken me away of late. You wouldn’t call it escapist though, because that’s such a pejorative term, but now that I’ve thought about it, I’m not so sure it should be, and it’s becoming increasingly clear to me that the divide is not so firm at all.

It’s about time for a Diana Athill reference, I think. Though she’s a memoirist like Elizabeth Gilbert, and one that people rave about with just as much enthusiasm, but for some reason I actually do plan to read Athill’s memoir one of these days, and I trust the wisdom implicit in what she has to say. My impression is that by reading Athill, we learn about the world through her prism, where in reading Eat Pray Love, we get Elizabeth Gilbert over and over. (Forgive me as I speculate about two books I haven’t read. And correct me if I’m wrong). Perhaps also it’s important that Athill is old and has years of experience, while Gilbert just once took a really great vacation.

Athill is quoted as saying, “Anything absorbing makes you become not ‘I’ but ‘eye’–you escape the ego.” And so is this the kind of escape we’re talking about? What Lebowitz is after? That with the best kind of books we get the world, get out of ourselves for a while, forget our problems.

Perhaps reading is a bit like love. Just when we’re not actively out looking for “help, answers and perspective”, that’s when we might actually stand a chance of finding it.

January 21, 2010

Pre-Swiftian Love Story

Poet P.K. Page, who died last week, has been eulogized aplenty since then, and I don’t really have much to add to the chorus, except that she was certainly an extraordinary person (as demonstrated by this brilliant obituary by Sandra Martin at the Globe & Mail) and I’m glad I got to meet her once. Though I spent only a little time in her presence, that presence was unforgettable and she was everything they said.

Less eulogized, however, has been Erich Segal, author of the novel Love Story, who died the other day at the age of 72. When I was twelve, I found a library copy of this novel in a desk at school (checked out under someone else’s name) and I stole it. Proceeded then to worship it through my unlovable teen years in hope that a hockey-playing, MG-driving, heir to a great fortune might just fall in love with me before I died of leukemia, even though I was neither Ali McGraw nor a musical prodigy. Even though I didn’t love Mozart or Bach, but I did love The Beatles, and I would have loved Oliver too, given the chance.

I haven’t read this book for quite awhile, but I read it so often back in the day that my original copy fell apart and I had to replace it (which wasn’t difficult. Love Story is always readily available used, usually displayed along with poetry collections by Rod McKuen). I am pretty sure that Love Story was not a great book, but I really loved it, and I must give credit to the man who wrote the book I’ve probably read more often than I’ll reread any other book in my life.

Though the book was wrong, and love does mean having to say you’re sorry, as unromantic as that sounds, but seeing as Jenny was only 25 when she died, perhaps she just didn’t have long enough to figure that out.

January 19, 2010

Family Literacy ALL WEEK LONG

Next Wednesday (January 27th) is Family Literacy Day, but we’re turning it into a week-long celebration here at Pickle Me This. Stay tuned for lots of children’s literature love, including an interview, a party and a fieldtrip. Check out their website to find an event where you can take part, or register your own.

Next Wednesday (January 27th) is Family Literacy Day, but we’re turning it into a week-long celebration here at Pickle Me This. Stay tuned for lots of children’s literature love, including an interview, a party and a fieldtrip. Check out their website to find an event where you can take part, or register your own.

January 13, 2010

Can-Lit and the Teenagers

“Upon reflection, I wondered again why Canadian literature isn’t able to connect with the teenage audience,” wrote Michael Bryson on his blog a while ago, which I thought was an interesting thing to wonder. And certainly not anything I’d much wondered about myself, because I rarely think of teenagers very much anymore, except to be a bit intimidated when I squeeze by them on the sidewalk.

Oh, teenagers, ye of the famously undeveloped brains. Though why did nobody tell me then? When I was a teenager, full of angst, and pain, and feeling, I do wish that someone had pointed out the fact that my brain wasn’t actually built and so nothing I felt really mattered yet. Which turned out to be quite true, in retrospect, but I might have been unwilling to face such a fact at that time. A time in which I was ready to die for the right to talk on the phone for six consecutive hours, and my favourite TV show was Party of Five.

The number of things that annoy me are legion, but up at the top would be people who carry with them any negative literary opinion formed by high school English class. No, worse– people who claim they don’t read because their high school English teachers broke down literature into such tiny pieces that they ruined the whole sport. (You can find evidence of this “breaking down” in any text annotated by a high school student, wherein each instance of “light” and “dark” is highlighted, for example. Or wherever there’s a mention of “river” and someone has written “=life”.) These people not understanding that high school is to teach you to learn how to learn first and foremost, and that perhaps all our closest-held opinions could serve to be re-evaluated once a decade or so.

Still, the greatest literary tragedy of them all, I think, is The Stone Angel as taught in Canadian high schools. Does this still happen? Is there a more inappropriate book out there? I reread it recently, and found it powerful (though far from Margaret Lawrence’s best), but could not understand how it could be expected to resonate with a sixteen year old. An extraordinary sixteen year old, perhaps, but most of us were far from that.

So what would be better? What’s a fully-grown Canadian book that could rock a teenage world? And don’t just think any old book with a youthful protagonist will do– a teenager can spot a phony a mile away. You know, the youthful protagonist who is always the cleverest person in the room (and in the book) so as to a) avoid complexities of character b) make sure we know the author is smart and not just writing YA pap c) reinvent the universe to realize ex-nerd author’s youthful fantasies concerning triumph and domination of a just world.

Help Me, Jacques Cousteau by Gil Adamson might work though. Fruit by Brian Francis. When I was in high school, I thought Atwood’s Cat’s Eye is as wonderful as I still do. Maybe Stunt? Alayna Munce’s When I Was Young and In My Prime? Rebecca Rosenblum’s Once. I think Alice Munro’s Who Do You Think You Are would be better than Lives of Girls and Women. The Diviners instead of The Stone Angel (if they could stomach Morag’s stallion). And Lisa Moore’s Alligator, perhaps? Lullabies for Little Criminals?

Or am I mistaken, to suppose that a teenage reader requires a protagonist with shared concerns? Could teenagers be smarter or dumber than they look? What are they (and we) missing? And I know I’ve got some high school English teachers among my readership of six, and I’d be interested to know your opinion, as well as that of anyone else who has one.

January 9, 2010