March 6, 2017

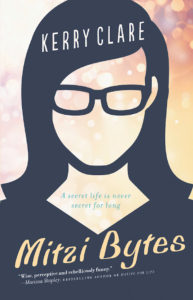

Mitzi Bytes: The Soundtrack

I believe it was Ernest Hemingway who once said that a novel is not a novel until it has both its own pinterest board AND a soundtrack, and while I’ve satisfied all terms on the former front, the latter is the final item on my agenda before my book comes out next week. And it’s such a pleasure to deliver. I hope that you enjoy it as much as I enjoyed creating it.

1. “Lover of Mine,” by Alannah Myles

While my novel is fiction, it’s made up of bits and pieces of the world as I know it, and one experience I do share with my protagonist is that of having one’s hair catch on fire at karaoke. I’ve always embellished this story (because lying is what I do best: hence my propensity for fiction) and unlike my character, I was not on stage singing “Lover of Mine,” by Alannah Myles, when the fire occurred. While I had been singing that night, I’d returned to my place in the audience and then my hair got too close to a tea light. But I have told the story so many times that in my mind now I was indeed on stage when the flames broke out, just as Sarah in my novel was. I have her singing “Lover of Mine” because it’s my favourite song to sing in the shower, and while there are rumours going around that I only wrote my novel in order to have an excuse to sing karaoke at the book launch, it’s not remotely true.

2. “If Not For You, by George Harrison

My favourite part in the novel was not written until the third or fourth draft, and it’s two scenes, the first in which Sarah and her husband Chris have an altercation that almost makes me cry when I read it, and then the part where he tries to explain what he meant, what he said. He paraphrases lyrics from this song, which is by Bob Dylan, but I love George Harrison’s version of it best. I remember listening to this song over and over years ago and yearning for someone to love this much. Also, while readers have mentioned that the male characters in the novel are not as realized as the women, I want to affirm that Sarah’s husband Chris is the least robotic man I’ve ever rendered in fiction, and for me this is a stunning achievement.

3. “Gypsies, Tramps and Thieves,” by Cher

This is actually one of my favourite songs to sing at karaoke (apart from “Bad Bad Leroy Brown and “Almost Paradise [Love Theme from Footloose]”) and I taught it to my children, who fell in love with it. I didn’t realize the implications of this until they started asking me why the singer’s daddy would have shot the boy they picked up south of Mobile if he’d known what he’d done, and why Mama was dancing for money. So I just rolled with it, and decided this was a great opportunity for my children to learn about accidental pregnancies, which you don’t necessarily have to be born in the wagon of a travelling show to know something of. In the novel, Sarah’s daughters are singing this song in the backseat of the car (which, n.b., is also fiction: I don’t have a car) while she’s considering Virginia Woolf and the multiplicity of selves, something that Cher in her various incarnations could probably tell us a great deal about. (I take pride in Woolf and Cher existing together in the same sentence in my novel. Not enough writers have made this connection.)

4. “The Harper Valley PTA,” by Jeannie C. Riley

This song doesn’t turn up in the book, but the song’s narrative of small minded people condemning a mother for her unconventional approach to life is a theme—witness Sarah’s dread every time she approaches the school yard to pick up her children. But I hope that readers will see this as an illustration too of Sarah’s own small-mindedness in how she approaches the other parents she meets. Sarah is not entirely wrong about the mothers, but she doesn’t consider that she’s one of them in many ways and that perhaps they’re also worthy of more generosity of spirit than she shows them.

5. “As Cool As I Am,” by Dar Williams

“And then I go outside to join the others, yeah, I am the others…” is a line from this song, which is about the trouble women have relating to other women, some women’s insistence in seeing themselves as apart from the rest. The trick being that women are just as multitudinous as the selves Virginia Woolf refers to, but this detail keeps surprising us. The solution, as I write, is that not women need to be more supportive of each other and all think the same, rah rah sisterhood, because how boring would that be, but instead that we need to make more space and allowance for difference. We need to be cool with other women not liking us. But no, Dar is right too—we should not be afraid of women.

6. “We Shall Not Be Moved,” by Mavis Staples

I love this song as a song of resistance. I wanted to write about a woman who refused to yield to everybody’s expectations of her, for better or for worse, and this song underlines that spirit.

7. “You’re Never Fully Dressed Without a Smile,” from the Annie Soundtrack

I have loved the 1982 version of Annie for nearly my entire life, and so it was to my great joy that my daughter fell in love with it too during the summer I wrote Mitzi Bytes. Every day she watched the movie while I wrote 1000 words and the baby slept, and that was how this book got written, a most miraculous arrangement. (The 2014 version of Annie would come out later that year and we loved it just as much.)

8. “History Remade”, by the Fembots

In the first draft of the novel, Mitzi Bytes was obviously set in Toronto, but in order that the story might have greater global appeal, it was edited to be less specific. But discerning readers might still recognize the city, especially the reference to the park where there had been race riots during the 1930s. Those same riots are mentioned in this song (“Here’s where the rioters raged over baseball and race…) by the Fembots from their 2005 album, The City.

9. “Virginia Woolf,” by the Indigo Girls

“And here’s a young girl/ On a kind of a telephone line through time/ And the voice at the other end comes like a long lost friend/ So I know I’m all right/ Life will come and life will go/ Still I feel it’s all right/ Cause I just got a letter to my soul/ And when my whole life is on the tip of my tongue/ Empty pages for the no longer young/ The apathy of time laughs in my face /You say “each life has its place”” I reread To the Lighthouse the summer I wrote this book, which is how that novel made it into the story, but it belongs there. I have long found so many connections between Woolf and blogging, and the connection described in the song indeed reminds me of blogs, voices like long lost friends. They particularly felt like that when blogs were new.

10. “I Feel the Earth Move,” by Carole King

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MOKx0xy8QE8

This song is included because when Sarah has sex with her husband for the first time, this very tall but otherwise nondescript (apart from his vile underpants) man she’s falling in love with turns out to have surprisingly remarkable sexual talents.

11. My Ding-A-Ling, by Chuck Berry

For a massive prude, it was surprising to me that so many penises kept turning up in my novel. “My Ding-A-Ling” is mentioned at Sarah’s book club meeting where they’re reading To the Lighthouse (phallic) and her friend is worried about her son who keeps exposing himself at daycare, and it turns out that this song is one of his favourites.

12. “Ripple,” by the Grateful Dead

There should be a long silence on this soundtrack in homage to the album that Sarah’s brother-in-law Evan will never actually get around to making, even though he crowd-sourced it and everything. A lying dirtbag, Evan is a total loser who fancies himself as a genius, but his greatest claim is some regional success in a second-tier Grateful Dead cover band.

13. “The Greatest Love of All”, by Whitney Houston

I hope that anybody finding Mitzi Bytes hard to get through (though I can’t imagine HOW THIS WOULD BE POSSIBLE) will persevere when they know that the last two sentences of the novel reference “The Greatest Love of All.” And to anyone who might find that off-putting, well, perhaps we were never meant to be…

14. “Oh, That Mitzi,” by Maurice Chevalier

I continue to be grateful to my friend Roseanne Carrara for bringing this song to my attention with its absolutely perfect line: “Should I be brave and misbehave?” Inspired by my gutsy character, my own answer to question these days is mostly, YES.

*Thanks to my husband for the Mitzi Bytes/Hard Days Night image here. Without your love I’d be nowhere at all, and utterly graphic designless.

March 5, 2017

Mitzi Bytes in the World

And now is the time we all bow down to publicists, because mine has done the most stunning job imaginable of getting Mitzi Bytes out into the world, as has certain online retailers which have apparently shipped pre-ordered copies even though the book doesn’t come out for another week. It’s all very exciting. This week, my mind was blown when Mitzi Bytes was called “an entertaining and insightful read” by actual HELLO! Canada. I got my first blogger review, from Tegan at One Mama Reads, which thrilled me to no end, particularly when she talked about the book as a series of juxtapositions. In preparation for my upcoming launch, I got to answer five great questions about the book from the good people at IFOA. And Mitzi Bytes is on “The Savvy Guide to March” at Savvy Mom and they called it “a beautifully penned story about truth, friendship, motherhood, and discovering who you are really are.” Also, someone else wrote a review and gave it 3/10, calling it slow and boring, but I kind of love that, because somebody hating your book is an authorial milestone and means that people beyond my immediate family are reading it. And in most important news, my friend Denise made a Mitzi Bytes cake. Seriously. This book and I have been very lucky.

March 3, 2017

Little Blue Chair, by Cary Fagan and Madeline Kloepper

Little Blue Chair, by Cary Fagan and Madeline Kloepper, is the kind of book you finishe reading with your family, and then there’s a split-second of silence which will be broken by someone saying, “That was a good one.” Everybody’s nodding.” It’s a familiar story, the kind we’ve read so many times before, but it’s just so deftly executed that you’ve got to admire it. And there’s plenty else to admire about it besides that.

It’s a something-from-nothing circle-of-life tale, and at its centre is a chair. A little chair, the kind you must contort your body into if you’re visiting a preschool, but this chair belongs to Boo and it’s the seat of his imagination. Fagan shows him using it to read, to build forts, to climb on, and he even falls asleep on it. (He sits on it too.) When Boo outgrows his chair, his mom puts it out on the lawn with a sign that says, “Please take me,” and therein because a most excellent adventure.

Do you ever wonder what happens to the things you put out at the end of your driveway? We’ve gotten rid of an antique bed frame, a busted stroller, a repulsive carpet, a trundle bed, a futon frame, a decapitated rocking horse, and several other objects that way. Moreover our coffee table, desk chair, and many other items in our household joined us in a similar fashion. After reading The Little Blue Chair, I’ll never imagine an item’s narrative trajectory from curbside as anything normal again.

A rattling old pick-up comes by and picks up (of course) Book’s chair, and the drive sells it to a junk shop. A woman buys it and uses the chair to sit her plant pot, but then the plant grows up, she plants it in the ground, and doesn’t need it anymore. And so back out to the curb it goes, where it gets picked up by a sea captain who uses it to have his daughter sit beside him as they sail across the ocean. When they’re finished with their journeys, the leave the chair on the beach, where a man finds it and uses it to give children rides on elephants.

And so on and so on, the most extraordinary travels, through the postal system and up a tree, and round and round on a ferris wheel (and oh, I cringed a bit thinking of the lax safety standards that might make that possible. I’d probably find a different place to sit if that were me…).

And on it goes, another child finding it and using it as the seat of his imaginative adventures, but then there is a misadventure involving balloons and one thing leads to another.

You might be able to imagine what happen next. Somebody finds the chair, and it’s a grown man who’s name is Boo, and even though the chair has been painted he can see where the paint has chipped and he can tell that this little chair is familiar. And quite conveniently, Book has a little person of his own at home for whom the little chair is precisely the right size, and she declares it perfect.

March 1, 2017

May Cause Love, by Kassi Underwood

I never had what Kassi Underwood terms as a “post-abortion meltdown”, which is the sentence I initially planned to open this review with, but then upon pondering I started to recall things I’d long ago forgotten. Such as that in the months after my abortion, I started working with a colleague whose girlfriend was pregnant, accidentally, and they were making a go of it together, and everything about their arrangement made me feel incredibly lonely. I would become unnecessarily preoccupied with the details of their lives. I feared that if I’d perhaps squandered my one chance to have a family. I remember a conversation with my best friend about reconciling feminist principles with my sadness about my situation, and then I remember waking up on the first day of what would have been the last month of my pregnancy and crying hysterically without even knowing why, as though my body knew before my mind did that something had been lost. But I also know that I felt much better after that. And later that year I would get the woman symbol tattooed upon my ankle, as a way to remember without having to actually remember, and it must have worked because all this seems far away and vastly unimportant now. When I look at the tattoo on my ankle, I don’t even remember that my abortion was a reason for it. “My abortion is the foundation of feminism,” is the thing I always say now, and it’s all conflated. My feminism is also a foundation of me. So you see, it’s with me always, even these if days I barely recognize it.

I never had what Kassi Underwood terms as a “post-abortion meltdown”, which is the sentence I initially planned to open this review with, but then upon pondering I started to recall things I’d long ago forgotten. Such as that in the months after my abortion, I started working with a colleague whose girlfriend was pregnant, accidentally, and they were making a go of it together, and everything about their arrangement made me feel incredibly lonely. I would become unnecessarily preoccupied with the details of their lives. I feared that if I’d perhaps squandered my one chance to have a family. I remember a conversation with my best friend about reconciling feminist principles with my sadness about my situation, and then I remember waking up on the first day of what would have been the last month of my pregnancy and crying hysterically without even knowing why, as though my body knew before my mind did that something had been lost. But I also know that I felt much better after that. And later that year I would get the woman symbol tattooed upon my ankle, as a way to remember without having to actually remember, and it must have worked because all this seems far away and vastly unimportant now. When I look at the tattoo on my ankle, I don’t even remember that my abortion was a reason for it. “My abortion is the foundation of feminism,” is the thing I always say now, and it’s all conflated. My feminism is also a foundation of me. So you see, it’s with me always, even these if days I barely recognize it.

(The interesting thing about the preceding paragraph is that not once do I affirm that in spite of my sadness, my abortion was still the right decision. When I wrote the paragraph, it never occurred to me to do so. And now after, I’ve gone back and tried to insert the sentence, but there is nowhere it fits properly. I’d only be writing it anyway to give assurance to you, my reader, but so now I’m going to do a radical thing and not even bother with that. Inspired by Kassi Underwood’s example, I am going to present my abortion as a thing that happened in my life that is ordinary enough and extraordinary enough to exist outside—and between, above and beyond—the simplified bounds of morality.)

So no, I didn’t have a “post-abortion meltdown” per-se, but then I don’t have Kassi Underwood’s remarkable flair for the dramatic. As a writer, a narrator, and a literary character, she comes across as a person who does nothing halfway, which might explain how she ended up with an alcohol addiction, but then it also explains how she turned her post-abortion story into a spiritual journey, what I’ve been calling the Eat Pray Love of abortion memoirs, the recently-released May Cause Love.

It was a book that made me really uncomfortable in places, which is saying something, because I talk about abortion all the time. But I’ve never talked about how the way that Underwood does, confronting uncomfortable truths about the experience, daring to consider its spiritual aspects. And so this was a book that expanded my mind. She begins her story in childhood, growing up in Kentucky with strong ideas about family and motherhood and the kind of woman she wants to be. It all goes a bit wrong (the love of her life is serving overseas, she’s in her first year at college and gets knocked up by a junkie) and she gets pregnant. The decision to have an abortion isn’t an agonizing one (and I am willing to entertain the notion that it only ever really is on television) but then it’s getting over it that’s the hard part. Acknowledging her sadness at not feeling ready to have her baby at that time, and then having to deal with the same guy having a baby with someone else just a couple of years later—her realization that she could have made a different choice. Getting over her abortion is also complicated though because it’s the urge to make good of her second chance that got her sober, that drove Underwood to make something of herself—who would she be without that drive? The questions she has and the ideas she grapples with aren’t the ones you ever read about in news coverage so fixed on the polarity of the abortion debate, but they’re so much more interesting, and kind, and useful.

The memoir chronicles her experiences learning about the spirituality of abortions, including taking part in a Japanese ritual for mourning abortions, to a Catholic post-abortion retreat (which is kind of horrifying, but Underwood’s lack of judgement is admirable [ps I now have this fantasy of telling pro-lifers that I’m not judging them, the same way they like to tell me that, and just seeing what they make of that]), a witchy Jewish circle of wild women helping her release her burden, meeting with an abortion grief specialist, and taking a five-day vow of silence in an isolated cabin in Vermont. She yearns to make peace with her decision, to find her way forward in her life, and to reconcile the seemingly contradictory experiences of her abortion—that the experience of pregnancy meant something to her, that her baby was a baby, that if she hadn’t had an abortion her ex-‘s daughter wouldn’t be alive today, and that somehow her abortion had been an act of love.

May Cause Love is a strange book, not just in terms of subject matter, but in structure and tone. As a narrator, Underwood is tricky, breezy, rendered unsteady sometimes in present tense instead of steeped in context and explanation. She’s also completely audacious, in the most incredible way—imagine not only not apologizing for owning your own soul, but demanding to be transported to a higher plane. It was so refreshing and illuminating to read about abortion in these terms, and while the storyline about the boy she spends years hung up was much less compelling to me than everything else, sometimes that’s the way that life goes. And life itself is full of surprises, just like this remarkable book.

February 28, 2017

Mitzi Bytes Events

Tomorrow is March, which is the month I get to start sharing Mitzi Bytes with the world. (!!!!) I’m looking forward to the following events, and I hope you can make it to some of them.

Tomorrow is March, which is the month I get to start sharing Mitzi Bytes with the world. (!!!!) I’m looking forward to the following events, and I hope you can make it to some of them.

- March 11, Whitby ON, Writers Community of Durham Region

- March 16, Toronto Launch, Ben McNally Books

- March 18, Peterborough ON, Hunter Street Books

- March 26, Uxbridge ON, Books and Brunch with Blue Heron Books

- April 4, Toronto ON, In Her Voice Reading Series, Dora Keogh Pub

- April 5, Toronto ON, Pivot Readings Series

- April 6-9, Hamilton ON, gritLIT Festival

- April 13, Toronto ON, the eh List Author Series, Toronto Public Library

- April 26, Waterloo ON, Wordsworth Books’ Appetite for Reading Book Club

- April 27, Toronto ON, Toronto Public Library Bibliobash

- May 5-7, Gananoque ON, Thousand Islands Writers Festival

- July 14-16, Lakefield ON, Lakefield Literary Festival

February 26, 2017

Son of a Trickster, by Eden Robinson

I went to see Eden Robinson at the Toronto Reference Library at the beginning of the month where she was in conversation with Miriam Toews. It was a perfect pairing, these two understated, seriously brilliant and totally hilarious writers together, and many of their sentences would trail off into hysterical laughter. The effect of all this being that when I finally picked up Son of a Trickster, its voice in my head was Toews’ cool easy cadence. This is not a complaint. Like Toews does, Robinson’s work is an uncanny breezily brutal, absurd humour juxtaposed with weighted tragedy, and there doesn’t actually appear to be anything of a juxtaposition at all.

I went to see Eden Robinson at the Toronto Reference Library at the beginning of the month where she was in conversation with Miriam Toews. It was a perfect pairing, these two understated, seriously brilliant and totally hilarious writers together, and many of their sentences would trail off into hysterical laughter. The effect of all this being that when I finally picked up Son of a Trickster, its voice in my head was Toews’ cool easy cadence. This is not a complaint. Like Toews does, Robinson’s work is an uncanny breezily brutal, absurd humour juxtaposed with weighted tragedy, and there doesn’t actually appear to be anything of a juxtaposition at all.

I loved Son of a Trickster, the first novel in ten years by Haisla/Heiltsuk Robinson. (“Her two previous novels…were written before she discovered she was gluten-intolerant and tend to be quite grim,” so goes her cheeky author bio.) At her TPL event, Robinson explained that this is a novel born of the 2008 financial meltdown, a problem that didn’t affect Canada so extensively, except for in small pockets we don’t hear about a lot, such as Robinson’s hometown of Kitimat, BC, where 535 workers lost their jobs when the pulp and paper mill closed in 2010. It’s in the aftermath of this that we find her main character Jared, sixteen-years-old and doing his best to keep things afloat. He makes money baking pot cookies and selling them to his classmates, but then he turns that money over to his father’s landlord so he won’t be made homeless as he struggles with addiction. Which Jared’s mother can know nothing about, because she’s terrifying (when she discovered a former boyfriend beating up Jared, she attacked the guy with a nail gun, fastening him to the floor) and if she finds out Jared is supporting the father who abandoned them, he might have (justifiable) reason to fear for his life.

The novel begins when Jared was small, when his parents were still together and in love, and it would be his father’s job loss at which point the whole arrangement falls apart. Although all was not always idyllic—his maternal grandmother had never liked Jared, as we learn in the novel’s first sentence. “‘Trickster,'” she tells him. “‘You still smell like lightning.'” As Toews herself pointed out at the event with Robinson, the title of the novel suggests it’s not exactly a spoiler to say that Jared’s grandmother might be onto something. And this book, the first of a trilogy (yay!), is the story of Jared’s journey to realizing exactly what that is. As he continues to hold his family afloat, suddenly the things he’s known to be true are revealed as fictions, and stories themselves take on a disturbing realism. About two thirds of the way through Son of a Trickster, a reader will feel herself stuck inside a Stephen King novel, which I mean in the very best way possible.

I loved it. The dialogue was so sharp and real, easing back and forth like a squash game at which everyone’s stoned, but never ever missing its mark. The characters are heartbreakingly realized, with soft spots and sharp edges, fuck-ups, and triumphs. I’d read reviews that the plot was uneven, but I didn’t experience it that way. While the book didn’t exactly fly by, I didn’t want it to. When I got to the end, I wanted there to be more, and thankfully there is more.

Next book, please.

February 25, 2017

Hometown Paper!

Mitzi Bytes and I were in the Peterborough Examiner the other week with plans for the upcoming launch at Hunter Street Books on March 18. Thanks to Joelle Kovach for a fun interview, a great piece, and for appreciating the novel so well. You can read her article here.

February 22, 2017

More Books on the Radio

I’m not kidding when I tell you that all I ever really wanted from this life was a books column on the radio, and so my spots on CBC Ontario Morning are indeed the culmination of a dream as well as a great deal of pleasure. What a thing: to get to talk about books you love. Today I talked about this excellent stack of reads, and if you didn’t hear it, you can listen again on the podcast. I come in at 40.40.

February 22, 2017

Where I’m Calling From

My book exists in the world, it does. I haven’t seen it yet, but it’s being couriered to my house this morning and so at some point in the not-distant future I will be holding it in my hands. Which I’m looking forward to, and not, because I much prefer anticipation to the fleetingness of a single moment. When a carton of The M Word anthologies arrived on my doorstep three years ago, I cried and cried, and not necessarily because of happiness. I remember feeling like kind of a fraud, because I’d published this book, but it wasn’t really my book, and while I was proud of it (and I still am) it felt somehow illegitimate. Would I ever be a real writer? And this, of course, is always the question.

And yet somehow I am a real writer, if the definition of the term is that I have deadlines coming up, just so I don’t have a single moment to take a breath before the book’s release. Which I’m not complaining about. The alternative would be no deadlines, and then I wouldn’t be a writer, and so I go forth, making it up as I go, which is the only way I’ve ever gone. In this way, being a blogger has been a tremendous boon to my writing life. Making it up as we go is our raison d’être.

Thankfully, apart from the flurry (and gift) of work, everything else is quiet—knock wood. We spent a long and low-key weekend partaking in the weird Spring-in-February weather, which I refuse to feel bad about because weather is weather. You take what they give you. The children continue to be funny and interesting, and also very very loud, but we know where they got that from. And the books pile up, and so many of them continue to be exceptional, original—there’s no running out of ideas yet. I love to read. I do so love to read, better than I love almost anything.

“Would you choose me or books,” my family asks me, and I always take the former, but not before hesitating. And not without some reluctance.

How fortunate we are to live in a world where both is not necessarily a spoil of riches.

February 19, 2017

Speedy Deletion: How I Tried and Failed to be on Wikipedia

Because I tell you everything, you have to know that I’ve wanted a Wikipedia page since 2008. This was the year my friend got a Wikipedia page. At the time, I barely had a “Published Works” page on my website, and my website was on Blogspot, and I had a long, long way to travel still. And all these details are a little shameful to admit, because we’re all supposed to be cool about this sort of thing. Like, “Oh, do I have a Wikipedia page? I had no idea, because I certainly don’t google myself weekly.” In my next life, I hope to be that cool, but in this life, I’m the woman who finds every mention of me or my work two days before Google Alerts does. Just once I would like Google Alerts to surprise me—for me this would be a definition of success. It would mean not only that my online mentions were turning up in substantial volumes, but also that I have better things to do than hunt about on the internet looking for them.

Anyway, last summer I decided that the time had finally arrived. I’d amassed a small body of work, some prizes, publication credits, and had a debut novel on the horizon. Because it would be cheating to create my own Wikipedia page (although I have been told that this happens all the time) I asked my husband to make mine for me, a really romantic gesture. And he did. It was really nice, and there I was amongst Canadian authors, and Canadian authors born in 1979, even. But it hadn’t even been a day before the Kerry Clare wiki was causing trouble.

The trouble at the start was kind of innocuous. They wanted references and citations, and this was understandable. There was nothing personal about it. I filled in the blanks and added the details. And then the next problem flagged was that my page was not connected to other pages, or referenced by them. Never mind—I’d fix that too. I connected my page to that of authors who’d been published in my anthology; I linked to an author who’d published me in her anthology. If I could I would have literally underlined that I am in fact a National Magazine Award-nominated author, or bolded the text at the very least. And this, the fact of being a National Magazine Award-nominated author, is really a very Canadian thing—you don’t even have to win. But the Wikipedia editors didn’t know this. (Perhaps “this” is also kind of sad. Don’t think I didn’t consider it.)

It was about four days into my career as a person with a Wikipedia page that things got more personal, that the notes on the discussion page began to be written by actual people as opposed to the template messages about links and additional citations. The people, who volunteered their time as Wikipedia editors, were not at all impressed by my accomplishments. And for awhile, I tried to engage with the process, to answer their questions, to fill in the blanks, to vouch for my own notability. But the more I tried, the more adamant the editors became. “Being nominated for an award does not make a person notable,” the editor explained. “She didn’t win the award. And her publication date is so far off into the future that it is likely, especially with the current state of publishing, that her book will never in fact be published.”

At this point I finally gave up. Although saying this suggests I had more agency in the matter than I actually did. Even if I hadn’t given up the fight to be on Wikipedia, I was on the shortlist for speedy deletion and it was probably going to happen anyway. But when I did give up, it was because it had dawned on me that battling to remain on Wikipedia was going to have to become my full-time job, and it was exhausting. Turns out I’m not so unnotable that I had absolutely nothing else to do with my time except battle it out with Wikipedia editors. If I’d devoted my life to staying on Wikipedia, I’d never be able to do anything else that was notable again.

I know some people who are as notable as dirt stuck to the bottom of my shoe, and they’re still on Wikipedia. How, I wonder, have they managed to pull it off? Perhaps it’s such a feat of incredible endurance that it makes a person notable after all?

A few lessons I took away from this: first, that the whole exercise is remarkably gendered. (The dirt on the bottom of the shoe people I refer to are male.) It was not lost on me that I am a woman who does have some accomplishments, and that my work was entirely dismissed without hesitation by a group of men who really knew nothing about those accomplishments, and who did not necessarily have any accomplishments of their own. Perhaps I am wrong about this final point, and I would be ecstatic if I were, in fact, but it does occur to me that profoundly successfully (or notable people) don’t necessarily have the time to be editing Wikipedia in the middle of the night. Anyway, the idea of mediocre men undermining a successful woman was not so mind-blowing—I don’t know where exactly, but I’ve heard that one before…

And the second lesson? That it’s really healthy for a person (especially a person who googles herself on a regular basis) to be reminded of her insignificance. I’m not being facetious. And that Wikipedia notability and other such metrics are not those with which we should necessarily gauge our success in the world. I mean, it would be nice, but these aren’t the things that matter. It’s good to know too one can be a total failure in all these respects, and still be entirely happy, and worthy of existence.