January 3, 2018

Looking Forward to 2018 Books

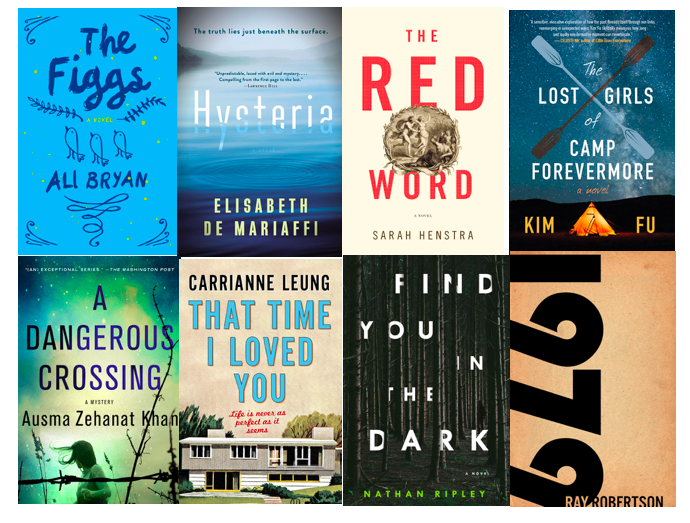

Happy New Year! I was on CBC Ontario Morning today talking about 2018 titles I’m really excited about. You can listen again here—I come on at 33.50.

Happy New Year! I was on CBC Ontario Morning today talking about 2018 titles I’m really excited about. You can listen again here—I come on at 33.50.

December 20, 2017

What a Gift

I broke, I did, in the very best way. I entered 2017 in a tizzy about whether to list my books or not to list them, and then in December I read Pamela Paul’s My Life With Bob and the decision was made: now I have a Bob (“book of books”) too. I’m even going to quit Goodreads, because keeping track of my reading was the one good thing that site did for me, but I’ve gone analogue. And I’m so happy about that.

I started blogging about books in 2007 because I needed a deeper way to engage with my reading—otherwise I was reading too quickly and the books passed me by. And while the blog has served me very well in this respect during the last ten years, I’ve found myself getting a little bit confused about its place in my reading life—if a book gets read but I don’t blog about it, does the book then even matter?

What I like about the Book of Books is that it’s antisocial, as reading is, as reading was meant to be. It reminds me that I read for my own sake, and for the books themselves, instead of as a public performance. I’ve had a busy year in which I’ve worked hard to confine my work (of which my blog is a part) to daytime hours, evenings preserved for (you guessed it…) reading. And so I’ve had less time to write about all the books that have come my way—and that’s okay.

Even though it bothers me a little bit (can you tell I’m neurotic?) that I never told you how much I adored The Lesser Bohemians, by Eimear McBride, even though I was pretty sure I wasn’t going to like it at all, or what a pleasure it was to read Catherine Graham’s deceptively c0mplex debut novel Quarry—maybe I won’t quit Goodreads after all because I like the opportunity to give stars to a book like that. I kind of went on book vacation at the end of month, so I read Celeste Ng’s Little Fires Everywhere purely for fun, and Claire Cameron’s The Last Neanderthal. It feels like a luxury to not have to formulate an opinion. A luxury just to be reading.

The poetry too! I’ve read a lot of poetry this year that meant a lot to me, but because I can’t/haven’t taken time to articulate those experiences, it’s almost as though they never happened. But they did. And I take solace from that—how much of a relationship between a reader and a book is just so absolutely personal and no one else will ever know about it. And nor should they, necessarily.

I never told you how much I loved S.K. Ali’s Saints and Misfits, or Jon McGregor’s Reservoir 13 (which is a wonderful companion to Rebecca Rosenblum’s So Much Love). I read the weirdly subversive The Misfortune of Marion Palm, by Emily Cullitan, in August, and didn’t tell anyone at all, which seemed deliciously indulgent. The book’s cover did match my hideous bathroom exactly, however, which I discovered while reading it in the bathtub, and I posted a photo on Instagram for posterity. I know some discerning minds get frustrated by #Bookstagram, and its artfully arranged books with no indication that anyone’s actually reading them. But I like it actually, that I get to read it, and you get to know about it, but I don’t have to do any more work than that.

Perhaps the moral this entire blog post is that I am tired.

Counting down to Friday, when I’m going to go offline for a week, maybe two, and devote my life to reading four fat biographies I’ve been saving for just this occasion. Last year I read bios of Monet, Jane Jacobs, and Shirley Jackson, and this year it’s going to be Svetlana Stalin, Joyce Wieland, Vita Sackville-West, and P.K. Page (whose name just took me far too long to remember. Not P.D. James, I knew, but my mind offered no alternatives. Maybe I am really really tired).

Anyway, so far I’m enjoying my Book of Books, and have relished the experience of adding each new title, making the joyous act of completing a book even more remarkable. And there are are so many blank lines and pages before me now—what a gift to be able to fill them.

December 18, 2017

Best Bookshops of 2017

There are ups and downs to the book publishing experience, but one definitively excellent thing about putting a book in the world is that it becomes your business to hang out in bookshops all the time. So that even though I hang out in bookshops all the time anyway, I got to do it even more often this year, and to visit legendary bookshops further afield. It was such a delight to visit the following bookshops this year on my travels, but before I get to my list I want to send a shout-out to Blue Heron Books in Uxbridge ON, which is one of my favourite bookstores ever, and to Words Worth Books in Waterloo ON, both of which had me for events this spring but not in-store, which means I didn’t get to go shopping. Which also means I’m probably due for a trip now. I’m also grateful to staff at Bay Bloor Indigo in Toronto and Chapters in Peterborough ON, who were really supportive of my book.

****

I had the best time in Edmonton in September, but a chance to visit Audreys was definitely a highlight. And not just because Mitzi Bytes was a staff pick and had been a bestseller there in May–but it certainly warmed my heart to the place! The story was huge with an amazing selection, and I particularly loved perusing the local authors section—I ended up choosing books by Claire Kelly and Jen Powley. I also bought books for my children and my husband back home, and each of the books was so well-received that it was almost a little bit magic. I could have browsed those shelves for hours…

*

Beggars Banquet Books, Gananoque ON

Beggars Banquet Books, Gananoque ON

It rained the whole weekend I was in Gananoque, but during a brief lull in the downpour, I hurried up the road to Beggars Banquet, which I already had an affinity for having become quite fond of owners Alison and Tom, who were charged with bookselling during the 1000 Island Writers Festival. Sometimes a second-hand bookshop [although Beggars Banquet sells books new and used!] smells of dust and must (and I mean that in the best way), but this one smelled of sawdust, brand new bookshelves, whose contents I explored for ages. I ended up getting Liane Moriarty’s Truly Madly Guilty, which I LOVED.

*

We launched Mitzi Bytes at Ben McNally Books in March, which was absolutely terrific. And then I got to return a week or so later for my friend Rebecca’s launch for So Much Love. Our most recent visit to this hallowed space was at the beginning of the month after going to see the Christmas windows at The Bay—I did some Christmas shopping, and also picked up My Life With Bob, by Pamela Paul, which I’d had my eye on for ages.

*

Curiosity House Books, Creemore ON

Curiosity House Books, Creemore ON

I got to go to Creemore three times this year! Once on the most hilarious road trip with Karma Brown, Jennifer Robson, and Kate Hilton for Authors for Indies, when we ate gummy bears and I laughed until I cried at the idea that Drew Berrymore had been previously been married to Red Green, among much other absurdity. I was so absolutely in love with Curiosity House Books that I knew we had to return there with my family in tow, which is what we did for my birthday in June, and we really did have the most perfect day. And then in September we were back again for the nearby Dunedin Literary Festival. And now I really want to check out their new sister store in Collingwood!

*

Happenstance Books and Yarns, Lakefield ON

Happenstance Books and Yarns, Lakefield ON

How had I never been so Happenstance? Not a huge store, but so well stocked, plus they sell knitting supplies too, and there is a candy store adjacent, which pleased my children exponentially. The first time I was there this summer (for the Lakefield Literary Festival) I picked up Laura Lippman’s Wilde Lake, which I adored, and then I returned later in August and got The Misfortune of Marion Palm, by Emily Culliton. They have a great selection, their titles for children in particular.

*

Hunter Street Books, Peterborough ON

Hunter Street Books, Peterborough ON

Remember when I got into a car accident on the way to Hunter Street Books and ended up owing a mechanic $800, and in the end considered it money well spent because the bookstore didn’t disappoint in the slightest? The store continues to be excellent. We launched Mitzi Bytes there in March and sold all the books, thanks to my parents’ spectacular networking skills, mostly, but still, it was a triumph. When we were back in town in August I ended up buying another stack—I have a problem with self control with their incredible selection of books, and can never buy just one.

*

Has a bookshop ever lived up to one’s expectations like Lexicon Books in Lunenburg, NS, though? Originally I was just excited to be visiting, and then they invited me to read alongside Johanna Skibsrud and Rebecca Silver Slayter. I was so excited to meet co-owner Alice, and when I walked into the store, co-owner Jo was sitting at the counter reading my book!! The store was so cozy and charming, and my family (who have seen a bookshop or two) declared their kids’ section the best ever. I ended up buying Alice’s staff pick, 300 Arguments, by Sarah Manguso, and took her comment card too by accident, and now it lives on my bedside table, the best souvenir ever.

*

This was our second trip to Lighthouse Books, corresponding with our annual camping weekend, and we were so excited to see Mitzi Bytes on the Canadian authors shelf, along with so many other great picks. I ended up buying A History of Wolves, by Emily Fredlund, and my children got a stuffed hedgehog and a teddy bear, we found out their all-time bestselling book was Where Is the Green Sheep, by Mem Fox (a classic!) and then we met a falconer. We can’t wait to be back next year!

*

One day last summer, I took my children across town on a road trip to Mabel’s Fable’s and it was the grandest adventure—we explored cool 1960s’ public art along Davisville Avenue, played in the Sharon Lois and Bram Playground, ate super fancy French cakes in a bakery full of weird rich people who were obsessed with dogs, and then we hit up Mabel’s Fables, and had the very best time. I ended up buying Scarborough, by Catherine Hernandez, from their adult selection. And yes, there was a cat called Mabel, the store’s namesake. It was totally worth the trip, and then some.

*

Oh my gosh, and speaking of being worth the trip! The opening of Sheree Fitch’s bookstore (in her barn at the end of an old dirt road) was the reason we went to Nova Scotia in the first place. We showed up the Monday after Canada Day for the store’s opening, along with hundreds of other Fitch fanatics—and we even made the local paper! It was everything—brimful of literary goodness, good people, music, sunshine, and magic. Plus a donkey, and a horse, and a sheep. We had the very best time—and then afterwards we drove up the road and got to play in the ocean.

*

We had nothing to do on Good Friday, and then I discovered that Toronto’s newest bookshop was open that day. And so we jumped on the streetcar and across town we went, and it was really so delightful, with golden ceilings, amazing wallpaper, so much space and light, and really great books. Something I particularly appreciated was that they managed to have that boutique exclusive feel in terms of inventory and atmosphere, but also coupled this with friendly customer service—which is rare. My one complaint was that my book wasn’t on their shelf, but I didn’t even actually complain, because everything else about the store was wonderful. And then when I returned in October for Jessica Westhead’s book launch for And Also Sharks, having made peace with the fact that they were too cool to stock my book and even forgiven them for it—my book was there! It was there. I could have my bookshop cake and eat it too; really, I could scarcely believe it. (PS On my first visit I got Eileen, by Ottessa Mosfegh, which seems seasonally appropriate, albeit not in an especially festive sense, but I am excited to begin reading it tonight!)

December 10, 2017

2017 Books of the Year

January seems like a long time ago now, when I was reading Hot Milk, by Deborah Levy, and drinking out of a mug that broke in October. Do you remember? I don’t even remember who that reader was really, or all the readers in between, but all the same, I am grateful to all the books and authors who made my 2017 so rich, bookishly speaking. The following titles are the ones that have particularly stayed with me.

Dr. Edith Crane and the Hares of Crawley Hall, by Suzette Mayr

F-Bomb: Dispatches From the War on Feminism, by Lauren McKeon

December 8, 2017

#2017BestNine

My Instagram #2017BestNine is pretty Mitzi Bytes-centric. I am grateful to everyone who helped make the experience of publishing the book a pleasure. Grateful too that my adorable children in their Jane Goodall/Woman Woman Halloween costumes snuck in there as well. Rad Women all around.

December 6, 2017

The Reason We Persist

December 6 is a weighty day in Canada as we remember the 14 women murdered in Montreal at Ecole Polytechnique in 1989, and women who are victims of violence (male violence) across this country and beyond, including more than a thousand missing and murdered Indigenous women. And every year it hits me harder and harder, the realization at how little women and their work and their voices and their bodies are valued. When I was a university student I used to sing in a choir and every year on December 6 we’d participate in a memorial for the murdered women, and while it moved me and broke my heart, the violence and rage that was the impetus for the massacre seemed far away then in time and place. I thought Montreal in 1989 was an outlier, that we’d got beyond it. But in the last few years, I’ve felt it closer and closer, more and more personally. Every December 6 for the last few years it’s occurred to me that I’ve realized an even deeper understanding of how much our society hates women than I’d had the year before. We are the same society in which a Canadian MP stood in the House of Parliament in 1982 to speak about domestic violence and her colleagues responded by laughing.

December 6 is a weighty day in Canada as we remember the 14 women murdered in Montreal at Ecole Polytechnique in 1989, and women who are victims of violence (male violence) across this country and beyond, including more than a thousand missing and murdered Indigenous women. And every year it hits me harder and harder, the realization at how little women and their work and their voices and their bodies are valued. When I was a university student I used to sing in a choir and every year on December 6 we’d participate in a memorial for the murdered women, and while it moved me and broke my heart, the violence and rage that was the impetus for the massacre seemed far away then in time and place. I thought Montreal in 1989 was an outlier, that we’d got beyond it. But in the last few years, I’ve felt it closer and closer, more and more personally. Every December 6 for the last few years it’s occurred to me that I’ve realized an even deeper understanding of how much our society hates women than I’d had the year before. We are the same society in which a Canadian MP stood in the House of Parliament in 1982 to speak about domestic violence and her colleagues responded by laughing.

Two posts by friends today got me thinking though, one writing about the complicatedness of her family’s celebration of Saint Nicholas Day on December 6, along with commemorating what happened in 1989. Another noting that it was her son’s birthday, a strange mix of feelings and emotions which underlines her intent to raise her boy to be a good man. And it’s these stories that make me feel better, actually, the way that memory and mourning and activism are built around the joyful and hopeful corners of our lives. All of it is the world and life itself, and no part is less worthy than any other for inclusion in the precious hours of our day. These joyful hopeful corners are why activism and politics mean anything, actually. They’re the reason we persist in hoping for and working for change.

December 6, 2017

My Life With Bob, by Pamela Paul

It’s here! I’m on vacation, in my reading life at least. Which is the way it happens every year sometime in the first half of December when I realize that I’m done. And that for the rest of the month I’ll be reading books just for fun, because I want to, unabashedly and uncritically and for the love of it (including four big books I’ve been saving for the holidays when I take time off-line, biographies of Vita Sackville-West, Svetlana Stalin, P.K. Page, and Joyce Wieland). I’ll be reading books just like I read Pamela Paul’s book, My Life With Bob: Flawed Heroine Keeps Book of Books, Plot Ensues, voraciously and with delight. I loved My Life With Bob, which I bought Friday, started reading Sunday evening, and finished last night whilst sitting on my kitchen table waiting for the pasta to boil.

It’s here! I’m on vacation, in my reading life at least. Which is the way it happens every year sometime in the first half of December when I realize that I’m done. And that for the rest of the month I’ll be reading books just for fun, because I want to, unabashedly and uncritically and for the love of it (including four big books I’ve been saving for the holidays when I take time off-line, biographies of Vita Sackville-West, Svetlana Stalin, P.K. Page, and Joyce Wieland). I’ll be reading books just like I read Pamela Paul’s book, My Life With Bob: Flawed Heroine Keeps Book of Books, Plot Ensues, voraciously and with delight. I loved My Life With Bob, which I bought Friday, started reading Sunday evening, and finished last night whilst sitting on my kitchen table waiting for the pasta to boil.

It’s the kind of book that makes you want to write a book just like it, an autobiography through reading. I would write about reading Tom’s Midnight Garden when my first baby was born, and the night after the second when I sat up breastfeeding and reading Where’d You Go, Bernadette? Reading Joan Didion for the first time on a tram in Hiroshima, which was around the time I started reading Margaret Drabble, the secondhand bookstore in Kobe that’s responsible for my connection with some of the writers I love best. Reading Astonishing Splashes of Colour, by Clare Morrall when I had pneumonia, and Fear of Flying on a plane to London, and The Robber Bride when I was far too young to properly understand anything it could tell me. I really could write an entire book like this—except it probably wouldn’t be as good as Pamela Paul’s.

“Bob” is Paul’s “Book of Books,” a list she’s been maintaining for decades of all the books she’s read. A list without annotations, but who needs annotations, because when she sees the titles they call forth an array of memories and stories. Forcing herself to read the entire Norton Anthology in college, the books through which she learned about New York before she lived there, reading Kafka on an ill-fated high school exchange to France, and her own Catch-22—”the unquenchable yearning to own books—to own books and suck the marrow out of them and then to feel sated rather than hungrier still.” These essays are not necessarily about the books in question, but about what it means to be a book person, to identify as a reader and have literature underline one’s lived experience.

The essays are so incredibly good. They are subtle and unnerving and do precisely what essays are supposed to do, which is to catch their reader off-guard and take her somewhere she wasn’t expecting. As life itself tends to do, and we follow Paul through college, and then post-college travel to Thailand, through the precarity of her early career, and such a stunning sad essay about her short-lived first marriage. Which leads to self-help, of course, and of the time Paul took a writing course with Lucy Grealy (right??) and how she gradually became a writer, as well as a reader. (And oh, do not forget the essay about her relationship with a man who liked the “Flashman” series. Needless to say, it didn’t work out, all this in an essay on the impossibility of getting along with someone whose books you do not like.) And then the essays on reading with her children, and the one on her father’s death and Edward St. Aubyn’s Patrick Melrose books, which don’t have so much to do with one another except that books are not so simple and so his death and the books become intertwined.

“Ultimately, the line between writer and reader blurs. Where, after all, does the story one person puts down on the page end and the person who reads those pages and makes them her own begin? To whom do books belong? The books we read and the books we write are ours and not ours. They’re also theirs.”

And as I begin my reading holidays, I’m quite ecstatic that this one is mine.

December 6, 2017

Books on the Radio

You can listen again to my book recommendations from today’s episode of CBC Ontario Morning on their podcast—I come in at 35:45 minutes. Although I was sorry to miss the chance to talk about Alison Watt’s Dazzle Patterns, on the 100th anniversary of the Halifax Explosion, no less! But in this case, “So Many Books, So Little Time,” is literally true. You should still check out the entire stack though.

You can listen again to my book recommendations from today’s episode of CBC Ontario Morning on their podcast—I come in at 35:45 minutes. Although I was sorry to miss the chance to talk about Alison Watt’s Dazzle Patterns, on the 100th anniversary of the Halifax Explosion, no less! But in this case, “So Many Books, So Little Time,” is literally true. You should still check out the entire stack though.

December 5, 2017

Short Story Splendour

Things Not to Do, by Jessica Westhead

Things Not to Do, by Jessica Westhead

I still remember my first Jessica Westhead short story, the title story from what would become her debut collection, And Also Sharks. It was 2012 at the Pivot Reading Series and I was sitting at the bar, and was enthralled: this was a voice like no other. A character whose voice is the light in her darkness, the force and will of it. I loved that entire book, and Westhead’s latest collection does not disappoint those of us who’ve been waiting for it. From Judy who has been working on her assertiveness, to the wedding DJ and Justin Bieber’s dad, and these stories are sad, funny and so quietly and powerfully subversive. I loved them.

A Bird on Every Tree, by Carol Bruneau

A Bird on Every Tree, by Carol Bruneau

This collection had me with its very first story, “The Race,” in which a disappointed war bride takes her chances in a marathon ocean swim, and as a swim-lit aficionado, I was besotted. The story was a feat of language—such sentences. And it’s not just that all the stories in the collection are that splendidly written, but that they manage to be with such incredible breath—historical fiction with the war bride, and then a nun via Lagos, a new mother in a greenhouse with her baby on her chest, a married couple unmoored in Italy, a mother leaves her grown son in Berlin: “We wake to the news that Osama Bin Laden is dead. My treasure in tow—the cheap, matted repro of Kollwitz’s Sacrifice—we catch our early morning flight to Rome.” Old flames and burning fires, and some stories in which the fire goes out completely. If this book were non-fiction, it would be an encyclopedia, because it’s got the whole wide world inside it.

The Whole Beautiful World, by Melissa Kuipers

The Whole Beautiful World, by Melissa Kuipers

And speaking of the whole word, let’s turn to Melissa Kuipers’ debut collection, which I read over a lovely couple of days in early October. Not all the stories were equally impressive, but those that set the standard were really great. I loved “Mourning Wreath”, a look back at a childhood friendship and this fantastic image of a letter written along the entire length of a roll of tape. Many of the stories take place within small, tight-knit Christian communities where the outside world is viewed with suspicion: the sight of a dead cow and a preacher’s invocation of hell commingle in “The Missionary Game.” I also really liked “Happy All The Time,” which tracks how a reaching college kid turns into a cult leader, and “Mattress Surfing,” worlds colliding when an ultrasound technician contemplates the tiredness of her romance with a air balloon pilot. Memorable and original, these are stories that have stuck with me.

What Can You Do, by Cynthia Flood

What Can You Do, by Cynthia Flood

I knew I was in very good company when I was out for dinner in late September, and we were talking about books, and every single one of us had something admiring to say about the work of Cynthia Flood. At that point I’d just read the first or second of the stories in her latest collection, What Can You Do, a collection I’d been well advised not to barrel through but instead to savour slowly, story by story. In the first story, a vacationing couple try to recreate a memory but find it haunting by disturbing stories in the present. In the second, a woman attending an event alone soon after a break-up takes the most satisfying revenge. And oh my gosh, the rumours of a kindergarten predator in “Wing Nut,” hiding behind a tree: how do we ever discern what is reality? Plus the girl who finds the letter from her dead mother hidden in a desk. I could go on. This isn’t a collection that’s easy to talk about as a whole, but every single one of its parts is worth an entire conversation. I like these stories, and they’re ones that I’ll return to.