August 11, 2015

Sistering by Jennifer Quist

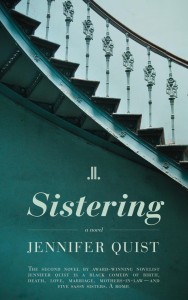

It would have saved me a whole lot of trouble if Sistering, by Jennifer Quist, had had a different cover. Something pink and quirky, a decorative font, I’m thinking a pair of legs sticking out of an open grave, feet in sparkly slippers. Instead of the sombre cover the book has now, which had me imagining I was reading something deep and serious. Although the actual cover did appeal to me too—stair steps like siblings, one after the other. This was a book about five sisters, the copy told me, which put me in mind of the early ’90s melodrama Sisters starring Sela Ward and (for a season) an early George Clooney, which I was totally obsessed with when I was 12. But Sistering was more Mary Hartman than Sisters, a morbid comedy. A romp, like the cover copy says, even though there is nothing rompish about the cover image as it stands.

It would have saved me a whole lot of trouble if Sistering, by Jennifer Quist, had had a different cover. Something pink and quirky, a decorative font, I’m thinking a pair of legs sticking out of an open grave, feet in sparkly slippers. Instead of the sombre cover the book has now, which had me imagining I was reading something deep and serious. Although the actual cover did appeal to me too—stair steps like siblings, one after the other. This was a book about five sisters, the copy told me, which put me in mind of the early ’90s melodrama Sisters starring Sela Ward and (for a season) an early George Clooney, which I was totally obsessed with when I was 12. But Sistering was more Mary Hartman than Sisters, a morbid comedy. A romp, like the cover copy says, even though there is nothing rompish about the cover image as it stands.

Which meant that I was confused at the beginning of the book by the strangeness of the characters, by their unnatural behaviour, and how nobody ever remarked on it. Although the story was compelling, and the writing was good, but I kept getting caught on certain points—how Suzanne is obsessed with her mother-in-law, for one. An affliction that’s happened to no one that I’ve ever known, but her sisters take it for granted. And then things with Suzanne and her mother-in-law take a particularly weird turn when the mother-in-law dies in an accident in her home, and Suzanne responds in a way that is, um, untraditional to say the least. At this point I was still not fully cognizant of the constructs of Quist’s literary universe—confused by the cover—and so the absurdity of the situation just seemed bizarre. Until I read further (compelling story, good writing, remember?) and realized that absurdity was the very point.

Quist is no stranger to odd books about death. Her first novel, Love Letters of the Angels of Death, was completely unique and well received, though with a twist at the end that I could not bring myself to bear for personal reasons, and so I was unable to fully appreciate it. This second book has a lighter touch, but with the same morbid preoccupations—one sister runs a funeral home, another mimes her own mother-in-law’s suicide, and another owns a shop creating cemetery monuments. Both books daring to present death as part of every day life, worth writing a romp about even. And in the end, the morbidness comes to takes a back seat to the sisters themselves, who were never meant to be ordinary or “relatable” in the first place—although they’re all familiar in many ways. Sometimes scarily so.

Over the course of the novel, Suzanne loses her mother-in-law, two of the other sisters find theirs are resurrected, babies are born, marriages are broken, so is an engagement, and there is a whole lot of gossip in the meantime under the guise of concern. That the sisters and their husbands are more types than fully realized characters is part of the exercise, as to exist in a large family is to be typecast—how else is one suppose to carve out her place? The types themselves setting up the potential for absurdity as characters behave accordingly. When nobody is just ordinary, neither is the plot.

I liked this book—though it took me some time to be sure about this, because for nearly the first half, I was mostly just confused. But once I figured it out—it’s supposed to be funny—it really was. Weird and original, a dark comedy indeed—not necessarily miles away from Sela Ward and Sisters either. This one that will appeal in particular to readers who loved Trevor Cole’s Practical Jean, and to anyone who ever had a pack of sisters.