January 31, 2020

Finding Lucy, by Eugenie Fernandes

I’m not reading picture books as avidly as I once was, which I guess was sort of an inevitable development. Ten years ago, when I had my first baby and was at a loss as to how to relate to her or the circumstances of my mother life, picture books were like a port in the storm, a place where my child’s and my interests actually converged, and they were how I related and connected to my daughter in those early days when her existence was still so alien and strange, and I was overwhelmed and always exhausted.

We’ve hung onto picture books all this time, however, because my children are four years apart, so we’ve stretched out early childhood for an awfully long time in our household, but now my youngest is six and a half, and she’s really into Ivy and Bean. And yes, of course, she reads us picture books now, and my eldest still enjoys them, but they’re not the meat of our literary diet as once upon a time they were. Which is why my #PictureBookFriday posts are getting few and far between. (Blogging tip: let your blog grow and change as you do. Don’t write posts that feel like chores.)

Writing this post doesn’t feel at all like a chore though, because it’s about Eugenie Fernandes’ Finding Lucy, a picture book I’m kind of obsessed with (and I think it’s also Fernades’ first picture book in quite some time). It mingles an old fashioned storybook sensibility (there are talking animals, and the cat is called “the cat”) with a dazzling and delightful abstraction, and the most delicious vocabulary. In fact, this is a book that relishes language just as much as it does colour and art, with words like “discombobulated,” “ferocious” and “atrocious.” “It’s utterly befuddling and baffling and piffling and dribbling and scribbling!” —so say the critics about Lucy’s attempt at a painting.

And yes, everybody has an opinion, as Lucy tries to paint her picture. She wants to paint the colour of laughter, she says, but then a reporter shows up, and then an elephant and a crocodile, and a chicken and a pig (with a pramfull of piglets) and a big city critic who arrives to assess Lucy’s work and have the final say. It’s a story about the necessity of sticking to one’s vision and not having your art be muddled from every elephant or crocodile who happens to wander by. But it’s also a story that’s so much more more than what it’s actually about, a book that’s rich and expansive, celebrating the exuberance of the creative spirit.

January 31, 2020

Perfect Pockets

I had the coziest reading week last week, with a backlog of books I wanted to review, and therefore I had to slow down with my reading, to spend some quality time with just one book while my reviewing got caught up. And the book I chose was The Great Believers, by Rebecca Makkai, which I had been on the verge of purchasing over and over again since it came out in 2018. I’d read her previous novel years ago, and found it middling, which made me wary of picking up this one, but there was nothing middling about its acclaim so I finally broke and bought it when I was at Hunter Street Books in Peterborough the other week, when I’d entered the store at five minutes before closing. And then I sat down to read it a few days later, and I’m so glad I read it the way I did, slow and easy, instead of in a hurry. It’s a giant, sprawling, ambitious story that’s maybe a bit too ambitious—as was her last book. But this one used that largeness and packed it with substance, with stuff, and even though I found some of the art stuff and connections to Paris in the 1920s a *bit* of stretch, still it stretched without breaking, and the connection worked. And her portrayal of the AIDs crisis in the 1980s was literally stunning, so devastating—and she wrote about it so beautifully. (See Makkai’s essay, “Writing Across Difference”, about how she—a straight woman—wrote successfully from the perspective of a gay man.) It was such a pleasure to not have to read the novel with a critical eye, but just to get lost in it—and I did. One of those reading experiences I will not soon forget, such a perfect pocket in time.

January 29, 2020

The Towers of Babylon, by Michelle Kaeser

I am just old enough to be wary of a novel whose plot is described as “track[ing] a group of hapless Millennials trying to find meaning in a world that consistently rejects them,” but am I ever glad I overcame such aversions to read Michelle Kaeser’s debut novel, The Towers of Babylon, whose characters are as complicated and wonderful as its exquisitely Toronto setting.

The novel—split into four sections—begins with Joly, whose advanced degrees in creative writing have left her interviewing for the same barista job she had in high school. She’s living with her brother in East End Toronto, writing stories that delight her but whose publications don’t even pay peanuts, and then she finds out that she’s pregnant, which was always going to be complicated, but in particular because her partner is Ben, once a philosophy student, always a social-anarchist, but now he’s got a job at the local bagel place and the house he shares with a group of roommates is about to be condemned. When she tells him she’s knocked up, he’s already drunk on his home brew, but isn’t too drunk to realize that a baby isn’t possible. And Joly doesn’t even really want a baby either, but she longs for a life where it might even be a question. “Now that she’s stormed through the door of thirty, the abortion instinct doesn’t ring out quite as loudly as it once did.”

The reader meets Joly’s best friend Lou in the novel’s first section, when Lou counsels Joly through the shock of her positive pregnancy test. On the surface, Lou seems to have it all together. She has a successful career (albeit a ridiculous one, as is obligatory in our time—she markets to marketers, selling space on billboard) and is married, living in her childhood home in the suburbs, which she purchased from her father. But all is not right, because she insists the house be preserved in time, from the era decades ago just before her mother died of cancer. And all is not serene in Lou’s marriage, as the reader will discover, and her career is at a breaking point. She’s got a better CV, but her situation is not all that improved over Joly’s.

And then Ben, Joly’s boyfriend, who should be the most charmless literary character I’ve read in ages (he calls Joly “doll” and when Joly tells him about her pregnancy, he asks her, “Can you even carry my mighty seed? Look at you. Look at me. Your runty frame would split right open!”) but there’s something endearing in his approach, and in his clumsy love and affection for Joly, and for his idealism and insistence upon it, as he lectures the Priest at his Anglican church on how to deliver her sermons, or causes trouble at the bagel place by agitating for workers’ rights and trying to start a union.

Religion plays a important part in the novel, as the title would suggest, and the Toronto skyline (the CN Tower in particular) underline the symbolism of this society in decline that Kaeser is writing about. And while sometimes the Tower of Babylon references read a bit too heavy-handed, the novel’s consideration of religion is nuanced and interesting, invoking more questions than answers about why these characters are turning to age-old superstition to put meaning into their lives. The novel is ambivalent about the role of religion in the modern world, presenting Ben and Lou as people who find meaning in faith, and then Joly’s brother Yannick, who completes the quartet and who is furious that his wife is insisting on their daughter’s baptism. For Yannick, religion doesn’t fill the void, but it doesn’t mean the void isn’t there as he gambles away his future on an all-consuming career in private equity and a passionless marriage. He doesn’t know how to solve the puzzle any more that anyone else in the novel does.

While The Towers of Babylon doesn’t offer solutions, however, what it does properly is entertain with robust and rollicking prose (the novel’s editor is the amazing Rosemary Nixon, and it shows), and offer a disquieting but still splendid illustration of life at a specific and anxiety-ridden moment in time. That its characters manage to be as lovable as they are flawed is a significant literary achievement, I think, and so is the fact that while the story is hard-hitting and unflinching, it also reads up a pleasure.

January 27, 2020

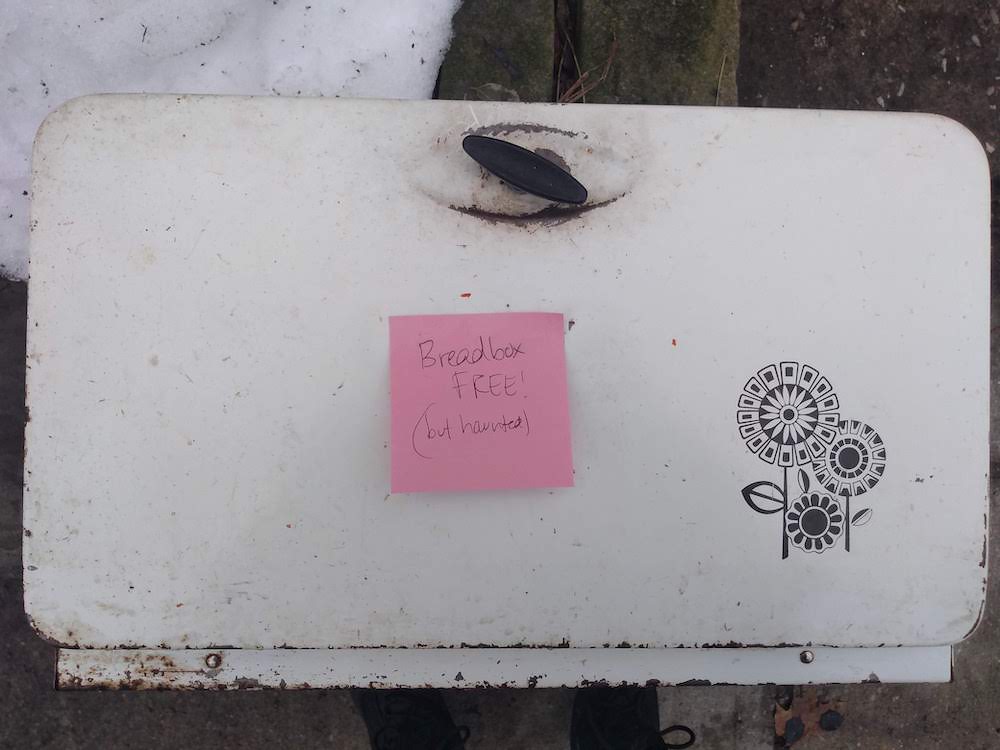

Free. But Haunted.

Farewell to our garage-sale acquired breadbox, which has been part of our family for the last decade. And never actually had bread in it very often, but was mostly used as a storage cupboard for odds and ends, and crackers, and coffee filters. And whose most salient feature was its tendency to have its door fall open just after something had been placed on the counter in front of it—last week, I lost a Pyrex bowl of egg-whites. (The bowl, mercifully, survived.) Several wine glasses being used by visiting friends also met their demise in such a fashion, and caused considerable embarrassment for all involved. I took to taping the breadbox shut when we had people over, which worked, but it still managed to catch us unaware. A poltergeist? (Or an ineffective bolt? But that’s boring…) And then yesterday, or next-door neighbour brought us over her breadbox, which is of a similar vintage (albeit without those delightful flowers). They’ve given up gluten and just had their kitchen remodelled, so the breadbox was redundant, so they passed it on, and now ours is the redundant one. We’ve put it out on the curb, but with a warning post-it. There are have been no takers. YET.

January 27, 2020

Gleanings

- Gurus, language scolds and comma queens

- Always keep a pot pie in the freezer.

- But here she is, walking through the world with her stuff and her thoughts.

- Down With Resolutions. To-Do Lists Are #Forever.

- It was fifty years ago today, January 26th 1970, that Bridge Over Troubled Water by Simon & Garfunkel hit the record shops.

- Nicknames that bully, nicknames that tease, nicknames that coddle. They underline a particular, not always flattering trait, and reduce the whole of you to that.

- Because teachers, whether we adore them or not, seem, especially to our small selves, a little god-like, not only for the power they wield, though there’s that (though that’s less and less), but their influence on us, which I wonder how often we even realize the power of… then, and now.

- Ideally, someone will bring over KFC to your chips and whiskey (or pop or club soda) party but that sort of fancy showboating is clearly not necessary.

- Oh, we built the deck the spring Forrest turned 2 because we had his birthday party there and that was also the time I planted the montana clematis against the posts of the deck.

- Seventeen is the time of tiny moments of panic that soon your kid won’t LIVE WITH YOU anymore. Let us not, as they say, “go there” as I am already in a fragile state.

- What do you do with your son’s toothbrush when he’s no longer alive. It’s just too much to think about.

- But a kindness tool kit required some thought…

- I admire the sky at multiple times of day and in all seasons—it inspires and invigorates me

- No matter where you are on earth, the sun rises at dawn.

- Just perfect! An anchor, a color of constancy, one we can rely on that will remind us to be big sky thinkers. Precisely the color we need this year.

January 27, 2020

Big: Stories About Life in Plus-Sized Bodies, by Christina Myers

The problem, when we talk about fatness—and body image, and body positivity, and health, and self-acceptance, and fatphobia and discrimination, and diet culture, the experience of feeling fat, and the experience of being fat, and so much more—is that we’re talking about a hundred different things and experiences, and that even though one thing often seems like it’s the flip-side of another—fat and skinny, for example—reality itself is more textured and complicated, and intersects with all kinds of ideas about race, and class, and gender.

Textured and complicated, however, are the perfect conditions for an interesting anthology, and this is why Big: Stories About Life in Plus-Sized Bodies, edited by Christina Myers, is such a rich and rewarding read. Sometimes anthologies themselves can be too heavy (not a pun, really, and I mean in terms of tone and length) but this one is designed to be inherently readable—and speaking of design, I love the cover.

Most contributors are women, though non-binary and genderqueer writers are also are present, and writer Tracy Manrell (who identifies as non-binary transmasculine) writes fascinatingly of the differences between being fat in a male and a female body.

Many writers consider relationships to weight that stretch back to childhood, and chart the long journey to learning to love their bodies. Others write about discrimination receiving health care, or about parenthood and pregnancy, or the simple challenge of finding clothes to fit.

Award winning humour writer Cassie Stocks writes about her love of fashion and deciding to sew her own clothes. Sonja Boon inventories the black articles of clothing in her closet. Jo Jefferson tells their story through swimsuits. Lynne Jones writes about abusive relationships. Jessie Blair struggles with gastric surgery. Amanda Scriver shares her journey toward radical self-love. Emily Allan writes “Ten Things I Love About Being Fat.” Other favourites are Heather M Jones “My Superpower is Invisibility,” Christina Myers’ “Fat Girl’s Guide to Eating and Drinking,” Andrea Hansell on battling with Spanx, Tara Mandarano on health struggles and her weight, and Susan Alexander on getting over decades of binge eating.

Big is definite worth picking up because it succeeds at its editor’s goal of being a book that “makes you ask questions: about the way you think and talk about your own body and other people’s bodies, about the world we live in and its lessons and obsessions, and about the words we use and how they shape us.”

January 23, 2020

Ten Years

I had some strange feelings about reflecting on the 2010s, mostly because I didn’t. There was a meme going around Instagram stories on New Year’s Eve in which we were supposed to list a highlight from each year, and I even tried to post it, but couldn’t figure out how to get the text to fit, which maybe means that the 2010s were the decade in which I stopped being technologically savvy.

But also, the years all blend together, and so much stayed the same. The decade before was much more filled with upheaval and revolution (they were my 20s after all) but in the 2010s were where the pieces started to fit. I stopped having babies, I began to have something like a career, I finally started publishing books, I made some wonderful new friendships, and maintained old ones. It’s been good, but the decade itself, its distinction, just seems particularly arbitrary. Like—even more than a decade should.

Or do I only think that because when the decade started, I was sitting in the very same place that I’m sitting right now?

Okay. not the exact same place. (We finally bought a new couch, remember?) But the same address, our apartment, which we moved into twelve years ago this April, the longest I’ve ever lived anywhere. I moved in as half of a young married couple, and now I’ve got two kids and I’m forty, and have been married almost 15 years. The little kids who lived next door moved out and went to university, and then moved back in again, although it didn’t do me much good when they did, because now they’re too old to babysit. But, as the middle section of To the Lighthouse, so astutely put it: Time Passes.

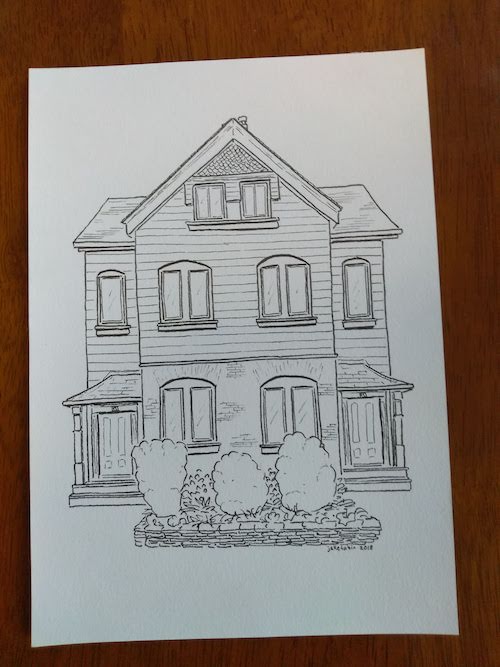

Imagining our own story as told from the perspective of the house as Woolf does in her novel (except with less war and death). The people coming and going, coats and jackets hung up on hooks and taken down again, early morning alarm clocks and dinners, and house guests, and holidays, and the quiet weeks where we’ve all gone away, and coming home again, an explosion of luggage, and the babies arriving, and late nights with the lights on while the world sleeps, and the babies grow, and all the books that come in and those that go back out again (returned to the library, or left on the garden walls for any takers), and the birthday parties, play dates, first day of schools, pencilled lines in the door-frame measuring from small to tall, and boots and shoes and sandals in a pile at the door, and the triumphs and disappointments, throughout anxiety and contentment, and these walls have contained it all. Even as spare rooms turned into nurseries and cribs turned into bunk-beds, and empty space turned into clutter—Lego, puzzles, and play-doh—and that ring on the carpet from where I put down a teapot and it melted. How places seem to hold us, even more than time does, and how a single place can hold so much, and so can a life.

January 23, 2020

Such a Fun Age, by Kiley Reid

And my catch-up of reviews of popular American books that everyone else read months ago concludes with Kiley Reid’s debut novel, which only came out a couple of weeks ago, so I’m back on top of things. A novel that caught my attention with a stunning cover, so many readers raving about it on Instagram, and that title, Such a Fun Age, which is a phrase I find so cloying—but also such a perfect ironic statement upon the moment in which we live.

So here’s the story: after a late night emergency, Alix Chamberlain calls her babysitter to take her three-year-old daughter, Briar, out of the house for a while. The babysitter is Emira, who’s Black, a 25-year-old college grad who feels stuck in a rut while all her friends’ careers are beginning to ascend. But she loves Briar, and knows she’s good at caring for her, and feels protective of the child too, because she can sense how Briar’s quirks make her mother uncomfortable, the way they mess with Alix’s efforts toward a picture perfect veneer. With Emira, though, Briar can be her strange old self, and the pair are dancing in the aisle of the upscale supermarket in the Chamberlain’s neighbourhood, Emira with her friend and dressed for the night out that Alix’s urgent call had just summoned her from, and a shopper (that lady?) decides that something doesn’t look right with this situation. Calling on the store security guard, who tell Emira she’s not allowed to leave the store with the child, and the whole thing is caught on video by another shopper in the store.

If this were an issue-driven novel (“a book about race in America”) this episode would be the point on which everything turns, but instead it’s just the beginning. And Emira herself is not terribly rattled by what happened in the store that night, because she’s got other things on her plate, and the reality of being Black in America is hardly novel to her anyway after 25 years of it. But Alix, Emira’s boss, is obsessed with the incident, and comes to feel the same about Emira herself, determined to help her, to save her, thinking she knows her well (she checks the texts on Emira’s phone after all), the babysitter’s well-being becoming a project that fills her spare time, which has been considerably more ample since Alix she’d failing to write the book she signed a contract for. (Alix has cobbled together a curious kind of career, the kind of career only a white woman could have, in which she writes letters to companies and asks for things, and they send them to her, and then she reviews them on her blog. She gets speaking opportunities and talks about feminism and agency, and is hoping for an in with Hillary Clinton’s campaign as a kind of legitimizing force, because Alix’s isn’t dumb, and knows her brand is 90% shadow and illusion.)

Such a Fun Age was reviewed in the New York Times the other week, and the review was less than flattering, calling the book “soapy,” as though that were a bad thing. By soapy, the reviewer really means readable, and it is. And it’s true that there’s a plot twist in the form of a connection between Alix and Emira that’s just a little too tidy. But what the reviewer missed is how a novel that’s so eminently readable can also be so well crafted (bumpy plot aside). The dialogue in this book is incredible, and the group scenes (a disastrous Thanksgiving dinner in particular) are so excellently orchestrated that would-be novelists could use this novel as a handbook. It’s a soapy-ish novel that manages to surpass its subject matter, to be about so much more than what it’s purported to be about. A pleasure to read and so smart at once, and utterly, bewitchingly, unsettling.

January 22, 2020

The Topeka School, by Ben Lerner

My week of catch-up reviews of popular American novels everybody else read ages ago—I NEVER promised to be a blogger with her finger on the pulse—continues with Ben Lerner’s The Topeka School, a novel I had zero interest in until I heard him on the since dearly departed podcast, The Cut on Tuesday—with his mother, no less. His mother who is Harriet Lerner, author of the iconic 1980s self-help book, The Dance of Anger, and we learn that she is fictionalized in her son’s new book, with her own point of view, even. And that The Topeka School is connected to Ben Lerner’s two previous novels about Adam Gordon, who is a literary representation of Lerner himself, and this new novel takes him back to his roots, to 1997, as 18-year-old Adam makes his way through his final year of high school, aspires to the highest echelons of school debate championship, having grown up in the state that gave the world Bob Dole who’d gone up against the beleaguered Bill Clinton in 1996 and lost. This is not a straightforward narrative, moving back and forth in time and between perspectives—Adam’s, his father’s, his mother’s, and a troubled classmate whom Adam had grown up with but who socially and intellectually falls behind, a ticking time bomb. The novel a study of male rage and anger, drawing connections between debate and rap stylings, and also to the national discourse, whose divisiveness begins heating up at this point until it boils over into the mess we have today.

January 21, 2020

Fleishman Is in Trouble, by Taffy Brodesser-Akner

I was going to say that I don’t know how I missed out on the Fleishman Is In Trouble hype, except it occurs to me that I totally do. I didn’t know anything about its author, Taffy Brodesser-Akner, first of all, a seasoned magazine writer, so her name wouldn’t have led me to pick the book up (especially since her name is Taffy, which is the funniest name since Flossie). And besides, she’d written a novel about a man in the spiral of a midlife crisis and the only thing I’d care about less than that is the story of a young man coming of age (ugh), so I just didn’t bother.

But then people kept posting about the novel on Instagram, and all the posts had comments from other people who’d read the book and loved it, so I was curious. So curious that I eventually put the book on hold at the library, except that I was more than 500th on the holds list… Which came up in conversation when my daughter was sitting on my lap one Sunday morning and we were reading over the 2019 New York Times top 100 list together—she likes to practice her reading. My husband overheard me commenting about my interest in the book, and the library hold situation, and had a brilliant idea—so I got the book for Christmas.

And by Boxing Day, I’d read the whole thing.

The novel is like a roller coaster, powered by fury, and the reader is flying by the seat of their pants from the first few pages. Fleishman of the title is Toby Fleishman, a successful doctor whose success will never compare to his high-flying talent agent wife’s—they’re getting divorced anyway. And New York, in the decade and a half since Toby was last single, has become a city packed with women who are seemingly desperate to have sex with him, which is certainly novel. It’s almost enough to make him get over his long time body image issues and insecurity due to his (lack of) height—but not quite.

But when Toby’s ex-wife, Rachel, drops off his kids one night and disappears, it puts a cramp in his style, not to mention makes arranging childcare difficult at a pivotal moment at work—Toby is up for a promotion. And this is just one more crime to add to the list of unforgivable things that Rachel has done over the course of their life together. Rachel, it seems, is a heinous bitch.

Sounds straightforward enough, right? And this novel starts off in the tradition of legendary male authors whose smutty books about fragile egos, hissy fits, and emotionally tumultuous love affairs about got to be literature because their narrators had penises. But then something strange happens, which is the appearance of a first person narrator who has been telling the story of Toby Fleishman all along. Like a reporter, even, which is not so surprising when it emerges that the narrator is the most unobstrusive Libby, a friend who’d met Fleishman twenty years before on their year abroad in Israel. And now, after many years and post-break-up, Fleishman has reached out to his old pals to help absorb the shock of his new life. Libby is, in fact, a reporter who finally quit work after the birth of her second child and has settled down for stay-at-home momhood in the supports, a situation which she is, shall we say, conflicted about. But where exactly is Libby coming from?

And this, sneakily and strangely, becomes the central question of the novel, which also eventually comes to fill in the mystery of where Rachel has been in her weeks-long absence, after Libby runs into her in a bagel place looking strangely dishevelled. A novel whose furious narrator writes about the invisibility of women, and how nobody ever listens to women’s stories anyway, unless there’s a man at their centre.

Which is shocking and profound, and the reader is implicated in this in the most terrific way, and the resolution to all this is never going to be tidy. It’s not simply a matter of Rachel’s story setting the record straight, or Libby even being capable of being objective about the situations she’s been presented with, because she has her own agenda. The peculiarity of this novel, an odd three-headed beast, being that it’s not one person who is the victim here, or even everyone. Or maybe it’s that it’s everybody and no one, and that life is too complicated for such obvious designations, and journalism often doesn’t seem up to the task of addressing these matters these days, but maybe here is where fiction comes in.