December 3, 2024

COLOURED TELEVISION, by Danzy Senna

TOO REAL is my main criticism of recent publishing satires like YELLOWFACE and now Danzy Senna’s COLOURED TELEVISION, just because it’s personal, strikes close the bone, offering a terrifying glimpse into the parts of my psyche I’d prefer not to look at. Apart from the trauma of that, however, I really liked this novel, even through witnessing its main character’s descent into disaster made me want to yell at the page, “Don’t do it.” COLOURED TELEVISION is a novel about race and class in America, about academia, about Hollywood, and marriage, and parenthood, and precarity, and about everything—possibly to a fault, but by design. After taking ten years of complete her magnum opus, a novel her artist husband has nicknamed “the Mulatto War & Peace,” Jane Gibson reconsiders the many life choices that has kept her family from reaching the middle class stability she longed for in her bohemian childhood. They’re currently spending a year house-sitting for a friend in the Hollywood Hills, and Jane’s been hoping selling her novel will finally turn their fortunes around. When this fails to transpire, she tells some fibs and steals a friend’s idea, hoping to pull off the plot twist and happy ending she’s been waiting for. Unsurprisingly, things do not go well. But they’re biting and funny and the book has real heart.

December 2, 2024

“All I Want Is Everything”

I don’t remember the first time I read The Diviners, but whenever it was, most of the richness of the novel was surely lost on me. February 2000 is the date inscribed below my name on the inside page of my New Canadian Library Edition, from a second-year Canadian fiction course in university, but I’m sure I read it at least once before that too. We’d studied Margaret Laurence’s earlier novel, The Stone Angel, in high school English, a curiosity in the curriculum—I’m not sure that 17-year-olds were ever that book’s ideal readers. And to my (very young) mind, for a long time, there wasn’t a clear distinction between its nonagenarian protagonist Hagar Shipley and The Diviners’ Morag Gunn, both of them untamed women with ugly first names, their characters rhyming (hag and rag), both past their prime, unfathomably elderly.

I reread The Diviners again in 2006, according to the second date on the flyleaf, when I was in my mid-20s, an experience that left no impression. My favourite of Laurence’s Manawaka books has always been The Fire Dwellers, a story of 1960s’ suburban housewife ennui, a novel that’s closer to my cultural and pop-cultural sensibilities, and I’ve returned to it a few times more recently. Unlike The Diviners, which stayed up on the shelf until after I’d gone to see the stage adaptation at The Stratford Festival in September (it was magnificent!) which blew my mind with the revelation that Morag Gunn is 47.

ONLY 47, which is to say in the prime of life. In my early-20s solipsism (um, as opposed to my current mid-40s solipsism!) I’d missed this entirely. Morag doesn’t help the cause by proclaiming, “But the plain fact is that I am forty-seven years old, and it seems fairly likely that I will be alone for the rest of my life…” at one point, sounding like some washed-up old hag(ar), although she doesn’t necessarily mean the fact of her solitude as a bad thing, something I didn’t understand before.

And this was just one of the many things I didn’t understand before, until I reread The Diviners again this month at the age of 45, my first experience of truly being able to access its depths and its wonders…

(The rest is available to paid subscribers on my Substack—you can read it here. And I still have two free substack subscriptions available to my blog reads. Send me an email at klclare AT gmail DOT com to claim one!)

November 20, 2024

Gleanings

- I’m enamoured with the language of small repair and I think that there’s instruction embedded in it from the “how-to” and right-to-repair world in how to live a life. I think of all the tiny repairs to my household just in the last year. I think of the still lifes I’ve made and used scotch tape and sticky tack to hold them in place. I think of the ways things fall into disrepair, that language, too: things fray, give up the ghost, they buckle, collapse, blow, crack, are torn, lose surface tension, become weathered, they fold, sour, unravel. They might fall (a cake, a bridge, a gate). There are kinds of repair: alterations, mending, rebuilding, filling, patching, re-wiring, re-jigging. We overhaul, darn, stitch, refurbish, fix, freshen. We can repair, and repair again.

- Because your house is the home of a quiltmaker and woodcutter, there are warm quilts for the bed and a woodshed full of dry fir and cedar for the fire. You keep replenishing both.

- Window display is still very much advent calendars because we’ll be selling those until the end of the month at which point we’ll fashion all the leftovers into a giant advent paper man and ceremonially burn him with a mince pie inside as an offering to the festive god (Santa) in exchange for good trade throughout December.

- It’s all real—the depravity and the life-affirmation, the distrust and the ride-or-die-ness, the shallowness and the deepness. Don’t let the Internet and all its tentacles (headlines, polls, social media, streaming, algorithms etc.) pull you out of your real, beautiful life and make you feel homeless. You are home among your people and your dreams, no matter what the “state of the world.” And the only way I know to make the “state of the world” less heinous is to trust what deserves trust, to ground on solid, relational ground, to start from there and then move outward.

- It’s when two swimmers move in tandem, like a choreographed dance that I am most amazed. Stroke on stroke, breath on breath; two perfectly synced flip turns. I leave feeling a small bit awestruck by what the human body can do.

- No amount of moving to the country and ignoring the news is going to make any of this change, so it’s everyone’s responsibility to work towards the world we want.

- A short book gives me the chance to travel to another place, be inside the mind of another person, or to learn about something new, but all from the comfort of my couch.

- There are dozens of fucked up things happening globally right now and this issue is not the most pressing, I know—not even close. But if I see another ChatCPT prompt presented as art, news or media, I will probably snap.

- You know that thing, when people ask if you were an animal, which animal would you be? Well, after much strenuous, existential, and deep thought (aka not that much thought at all), I decided if I were an animal, I would be a penguin. An Emperor penguin, to be specific. You wanna know how I came to that conclusion?

- When she opened the door to the fridge repairman, she didn’t foresee all the doors on the other side.

- I eventually decided that I just wasn’t cut out to be a novelist and focused on writing non-fiction pieces, usually about music. But then during the early lockdown days of 2020 I found myself daydreaming all the time, telling myself stories that I ended up thinking I could turn into a romance novel. I’d been reading romance novels for years; I don’t know why it hadn’t occurred to me to try to write one. It took being stuck at home with my two young kids in that stressful, uncertain situation for weeks on end for me to think, ‘What’s the opposite of this?” And the answer to that question turned out to be a romance story about young cute people living in New York. I ended up kind of desperately throwing myself into writing a book and sending out one chapter per week to a group of friends. That was the book that eventually got me my agent, but it didn’t get picked up by any publishers.

- In this world where mostly what I’ve been thinking and wondering and feeling lately is, pardon me, but “what the hell is going on?” again and again, I’m always so surprised when I remember … it’s always just the moments, isn’t it?

November 18, 2024

Garbage Bin

Last Tuesday, someone made me really furious, justifiably so, and there is something so delicious about righteous fury, it’s true, and it was the kind of thing that once upon a time I would have posted about on Twitter, receiving such satisfying feedback, my feelings justified, even rewarded with attention and sympathy. LIKE LIKE LIKE. I was even noticing how difficult it was to hold these feelings all by myself, how satisfying it would have been to post them instead (though I was proclaiming them; many thanks to the people I encountered IRL who got to hear all about it) and I was planning on getting around to doing so eventually on one platform or another (maybe this one) but then after some time had passed, I realized that I didn’t actually need to anymore. Screaming my feelings onto the internet did seem like a convenient way to offload them in the moment, but then it turned out that holding them for a little while did the very same trick, and there was insight in that, for me.

(Being angry on the internet actually only ever made me angrier. One day in 2018, in my peak internet rage period, I received an email from a friend informing me that my Facebook account had been hacked, and someone was posting expletives about men having the audacity to whistle in public…but it was actually just me posting an update. And while I still have the exact same feelings about men whistling in public [honestly, it’s shrill and obnoxious. Shut up], I’m no longer losing my shit about it, and we’re all better for this.)

I have had a sense, for a long time, but during the last thirteen months in particular, that a lot of people’s refusal to sit with their uncomfortable feelings has caused our communities a great deal of trouble, created even more conflict in a moment altogether too rife with it. Where the impulse to project one’s feelings in addition to or in lieu of actually feeling them has spilled over from social media feeds to be plastered on lampposts, where people are literally arguing back and forth via graffiti spray painted onto garbage bins, and I’m so tired of all of it, of other people putting their unprocessed feelings (including anxieties) EVERYWHERE, so screaming loud that I can’t even hear my own sensibilities.

And that’s a ME problem, which I’m going to attempt to solve by taking December and January off from my remaining social media platforms (and also by not joining Blue Sky, because there’s only so many voices I need in my head), in addition to avoiding local garbage bins and dealing with my rubbish at home.

November 18, 2024

The Knowing, by Tanya Talaga

As opposed to “The Knowing”—which Tanya Talaga explains in her book of the same name is a sense among Indigenous people of the truth as to what happened to themselves and their relations as part of the genocidal residential schools system in Canada—there is the fact that I knew nothing. Not an excuse, a plea for absolution, just a fact, and so I came to this book most humbly, a book that began with Talaga’s journey for the details of what happened to Annie, her great-great-grandmother, buried in an unmarked grave off the QEW expressway in Toronto, on the former grounds of a psychiatric hospital. Through her own research, in conjunction with the work of so many others, Talaga is able to piece together the story of Annie and her family, one of colonization, subjugation, but also survival (though sometimes not), and her quest for facts and records is its own thread in this many-threaded work, the obstacles in her way (poor record keeping, destroyed documents, other unavailable, and more) telling their own story of colonial power which continues to this day.

November 14, 2024

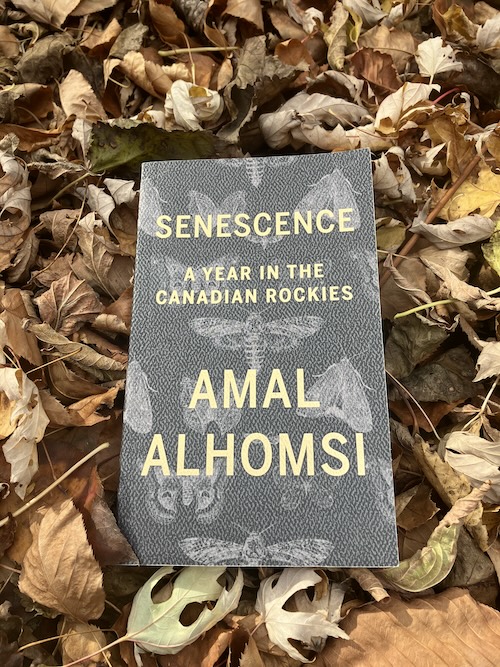

Senescence: A Year in the Canadian Rockies, by Amal Alhomsi

SENSESCENCE: A YEAR IN THE CANADIAN ROCKIES, by Amal Alhomsi, is as much about a year in the Canadian Rockies as Annie Dillard’s first book was about a creek, which is to say that it is about that, but it’s also about everything, about seeing, and being, and (dis)connection to nature, all from the particular viewpoint of a Syrian writer based in Alberta’s Bow Valley, which is not one encountered enough in nature writing. A tiny book that you can slip in your coat pocket, this one was one gorgeous gift after another.

“On the bank of the Bow I was duped. The world seemed still until it wasn’t. What use is a root if the earth it’s embedded in keeps spinning. This motion without consent is dizzying. You open a book and blink a few times, and before you know it, you are now where Mongolia was. A sea sponge, after nestling in a good spot, will move two millimetres an hour simply by breathing. In the morning I inhaled and there was a terrible noise; currents and killdeer and cudweed against the wind. Now there’s a fire near, and ash is riding the air like snow. I have done nothing but breathe, and the noise is now numb. Smog has a silence like ice, like blood. I have done it again; I came here to test the waters, then I was knee-deep in time, then I was swallowed.”

November 13, 2024

What She Said, by Elizabeth Renzetti

I can’t find an archived copy anywhere, but I swear I listened to Gloria Steinem about ten years ago in conversation with a supposedly feminist male radio host who would very soon after be exposed as a sexual predator, and what she was telling him was that when she’d first learned about patriarchy and sexual inequality decades earlier, she’d decided that there was nothing more urgent than letting other people, the people with power, know about it. Because once they knew, she thought, surely they would want to change things, to make the world more fair for women and girls. But then eventually, she explains, she realized that it wasn’t that these people didn’t know, it was that they didn’t care, and that whole lives, careers, industries, cultural identities were actually tied up in patriarchal systems and structures which were so much more deeply entrenched than she’d ever understood, and ten years ago I thought I knew what Gloria Steinem was talking about, but I had actually had no idea. The feminist backlash roller coaster ever since then is the very worst ride I’ve ever been on.

It’s a mindfuck that my excellent friend Elizabeth Renzetti has been documenting throughout her journalism career, including with her first essay collection, SHREWED. And now her follow-up, WHAT SHE SAID, six years later, finds readers at a moment, post pussy-hat, that is somehow even worse, in which we keep being told not to believe the evidence before our very eyes—that Kamala Harris was “unqualified,” for instance. That abortion bans are about anything more than controlling women’s bodies. That our men and boys are hurting, and we need to be thinking about their feelings, instead of having a societal conversation about the reasons for domestic violence rates being sky high.

It makes no sense, but the gift of WHAT SHE SAID is that Renzetti connects the dots enough that it almost does, and the reader can breathe a sigh of relief: it’s not just you, and it’s not just me, it’s the patriarchy (and it’s all around the world). Renzetti writes about sexual harassment and the reasons women don’t report; about gender inequality in the caring professions, which mean our most vulnerable suffer; about the disparities in women’s health, and how the politics of oppression are inextricably linked to the politics of reproduction; about who tells the stories in Hollywood; about the fraught relationship so many women have with money (and their entitlement to earn it); about whether women have a sell-by date; why it’s so hard for women leaders to be elected in politics; about the incredible abuse hurled at women in journalism; about the links between domestic abuse and terrorism; and about how the world is not designed for us (and the bros who are charged with engineering the future don’t see any problem with this status quo. And then finally (SPOILER ALERT), in her epilogue, Renzetti comes out as a Swiftie: “She bestrides the world like a tall, multi-instrumental, cat loving colossus… She is Taylor Swift, and there’s no one like her.” (If you’re a Toronto Star subscriber, you can read this beautiful, empowering essay online right now. I actually cut out the two page spread from Saturday’s paper, and I’m going to save it forever…)

She is Elizabeth Renzetti, and there is no one like her either, as brilliant (I promise you) as she is funny (and she is so very funny—that this book of brutal things can be filled with lines that made me LOL is really something). Medium height, but a cat lover too, and when this world enough to make your head start spinning, her book will help you realize that you’re not crazy and messed up, it’s just that the world is, but we are not alone in it.

November 13, 2024

Gets off the train half-drunk and it’s raining again…

“Gets off the train half-drunk and it’s raining again on the platform. Strikes him suddenly that he has no umbrella: and when, where. On the tram he had it. Station toilet he thinks, yes, messing with the lemonade. For Jesus’ sake, he’s had that thing years. He actually liked it. Climbs into a taxi, cash in his pocket, out towards the old ring road please.” —Sally Rooney, Intermezzo

November 12, 2024

Heartbreak is the National Anthem, by Rob Sheffield

“The Eras Tour is a journey through her past, starring all the Taylors she’s ever been, which means all the Taylors you’ve ever been.” —Rob Sheffield

The first time I heard Taylor Swift, it was 2009 and I was driving a rental van to The Junction to pick up a secondhand (recalled) drop-side crib I’d bought off Craigslist for my six-week-old baby, and “Love Story” came on the radio, and I just loved it (that bridge! That key change! How it recalls Katie and Tommy on the old porch watching the chickens peck the ground!).

Although Swift would remain otherwise peripheral to my experience for a while longer, until my daughter (by then 6) arrived home one day from daycamp reporting a song called “Bad Blood” that she’d overheard kids singing, and wanted to hear more of, and there was no going back after that (which was fine, because who doesn’t need a little music in our minds saying “It’s gonna be alright”?).

We’ve been a crew of Swifties ever since, mishearing the lyrics to “Blank Space,” going back to turning “Red,” being unsure about “Reputation” but eventually won over, leaning into the cringe on “Lover,” being rescued from pandemic doldrums by the magic of “Folklore” and “Evermore,” wondering about the auto-tune on “Midnights” and belting out the killer tracks on “TPD.”

And while we did not win the ticket lottery for her Eras Tour in Toronto, I am leaning into the shimmer of #Tayronto this month in lieu of more dreadful things I could be paying attention to, and part of that project was anticipating Rob Sheffield’s HEARTBREAK IS THE NATIONAL ANTHEM, a fun and engaging journey through the weird, wonderful, over-dramatic and TRUE world of Swift’s music and her remarkable career.

“Champagne Problems” was playing in the donut shop when I took this photo. Taylor Swift is omnipresent, and neither she nor I would have it any other way.

November 12, 2024

Three Things

- I purchased a shacket from Value Village two weeks ago (with the TAGS ON, even though they called it a “coatigan”) and it might be the very best garment I’ve ever worn, so perfectly cozy. I’m a few years behind on the trend, as usual, but every time I go outside it makes me happy, which is saying a lot for November.

- On Saturday night I was in the foot care aisle at Shoppers Drug Mart when “Release Me,” by Wilson Philips, started playing on the store speaker, so I took a short video on my phone and sent it to my cousin, alongside whom I was a WP superfan in the early 1990s, and then the next day she sent me a video of “You’re In Love” in the painkillers aisle of her Shoppers Drug Mart 1000 kilometres across the country

- I am midway through INTERMEZZO and enjoying it entirely.